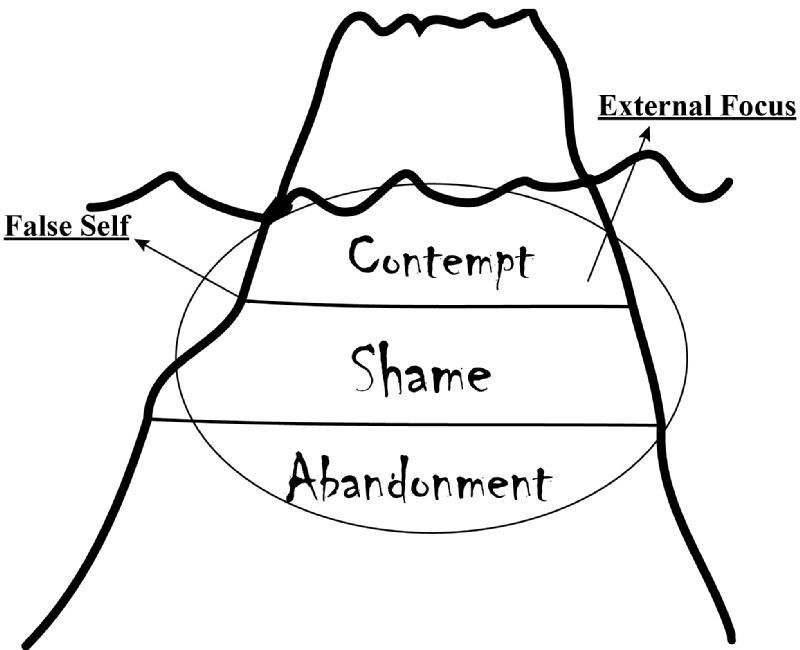

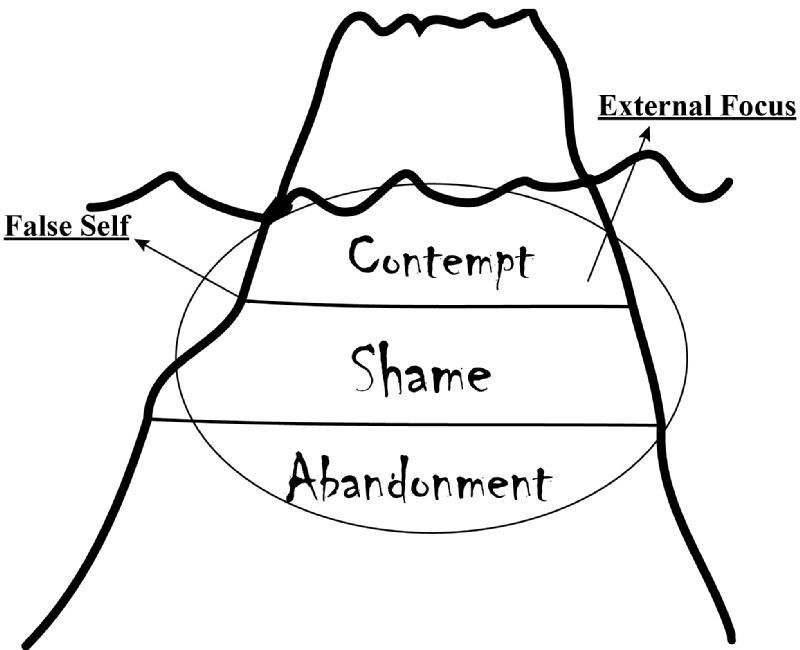

In order for children to survive the pain of their wounds they must learn to live outside themselves; i.e., they must develop an external focus [see Fig. 6]. In other words, the child must find distractions in their outer world to avoid the pain of their inner world. Everything outside of our own skin is our outer world, while our thoughts and feelings exist only in our inner world. We experience our feelings in our body while our thoughts are located in our mind.

External Focus

Children develop this external focus through a number of distractions such as imaginary friends, relationships with pets or stuffed animals, watching cartoons, and staying busy with play. Later the distraction may be video games, skateboarding, or sports. Kids who have a lot of pain have difficulty with inactivity and quite time. One will often hear them proclaim, “I’m bored! I can’t stand boredom!”

Figure 6: External Focus

In my work with teenagers, I encountered the “I can’t stand boredom” syndrome many times before I learned that it really is true for some. Many kids have trouble tolerating boredom not because of boredom itself, but because of what boredom represents to them. Boredom to these wounded kids is a red flag. It’s a signal that they are losing their external focus. As their attention begins to drift inward, anxiety starts to build because the next thing to come into their awareness would be their emotional pain. It rarely gets that far because the children or teenagers are compelled to take action to help them regain their external focus. A common scenario follows:

Billy, a teenager, is referred to counseling for habitually skipping school. Through the counseling process, it is discovered that this child’s father is alcoholic and that things at home are fairly chaotic most of the time. In order to keep an external focus and avoid his emotional pain, Billy has to remain actively involved and interested in class. However, every day, right after lunch Billy has a math class. He is not interested in math at all because he is not very good at it (competence issue) so it is only a short time before “boredom” sets in.

Billy tries to regain his external focus by staring out the window in a daydream. That works for about three minutes. Soon, he finds himself passing notes, shooting spitballs, or talking to his neighbor. Before long, the teacher is involved in disciplining Billy, again, for disrupting the classroom. Billy then gets into an argument with his teacher, who is “always picking on me” (externalization of contempt). The teacher takes him out into the hall where the next external focus, the principal, is approaching.

Billy has the option of going through this routine or avoiding it altogether by skipping the class. The easiest option is to skip class and find some way to regain his external focus. Sometimes he would get a friend to sneak off with him to go to hangout downtown, or he would sneak off onto the parking lot to drink or do drugs, or simply go home to watch videos, play on the Internet, or engage in some other distraction.

Acting-out is only one method that helps children distract from their emotional pain. Again, other methods include creating imaginary friends, having relationships with stuffed animals or pets, video games, comic books, cartoons, hyperactivity, and various other ways to stay outside of themselves.

Invented Self

Another thing a child must do in order to avoid her inner world and stay in her outer world is to unconsciously build a wall between her awareness and her unawareness. These “walls” are constructed automatically of psychological defense mechanisms and have been collectively referred to as “survival roles” because their function is to help children survive in the face of unmet dependency needs. Children learn to “cover up” their false self by projecting an image other people might find acceptable. This is often referred to as “wearing a mask.” I think of it as inventing a self [see Fig. 7] to cover up the false self because, “If people really knew me they would not like me (shame), and they would reject me (fear of more abandonment).

Figure 7: Invented Self

Children unwittingly invent and project these images, or survival roles, through the use of unconscious defense mechanisms in order to avoid the intolerable reality of their unmet needs. The pain is still there, but it is not as “in their face” as it would be due to one defense known as repression. Repression automatically pushes the pain deep into their subconscious until the child matures, and heals, enough to develop the psychological equipment to cope with it.

Survival roles also serve to help the child find ways to get her needs for time, attention, affection, and direction met. For example, in a dysfunctional family one parent gets caught up in some form of problematic behavior while the other gets caught up with trying to control or “fix” the problem parent. They get enmeshed with each other and the problem behavior while leaving less and less time to attend to anything else, including the children.

Family Hero:

When the first child comes along, he or she finds out fairly quickly that in order to get any time, attention, affection, and direction in this family he or she has to do something outstanding to get noticed. So this child usually becomes the Hero. There are two kinds of family heroes. The first is the flashy hero who gets all A’s, is captain of the football team, valedictorian, class president, head cheerleader or a combination of the above. The second type is the behind-the-scenes hero; aka the Responsible One or the Parentified Child. This is the child who comes home from school early every day, does the laundry, gets the mail, prepares dinner, does the dishes, takes care of the younger kids and, in essence, becomes a parent at ten years old.

Rebel/Scapegoat:

The second child usually becomes the Rebel or Scapegoat. They can rarely compete with the first child for the positive attention because the Hero has a head start. So the Rebel must settle for the next-best thing, i.e., negative attention. The Rebel gets time, attention, affection, and direction from teachers, principals, juvenile officers, counselors and anyone else who would try to help them. While they may not get the positive attention, they do end up getting the most attention. The parents must stop what they are doing to deal with this kid’s misbehavior because the school or juvenile office keeps calling.

Lost Child:

The third child cannot compete for the positive attention or the negative attention, so they don’t get any attention and become the Lost Child. In order to survive, this child relies on fantasy to get her needs partially met. An example of a Lost Child is the seven-year-old girl who is always somewhere in the background playing with a doll that she has had forever. One hardly ever notices that she is even there. She says nice things to the doll, combs its hair, tucks her in every night, rocks her to sleep and, in essence, creates a family of her own, vicariously getting her needs met by becoming a nurturing parent to the doll. The Lost Child may also have anywhere from eight to twelve stuffed animals on her bed at one time and knows each of them intimately. This child spends so much time in her fantasy world that she loses out on opportunities to make friends in the real world.

Family Mascot:

The fourth child, usually the Mascot, is the baby of the family. This child gets his needs met through being on stage. He or she is the class clown or the beauty queen. This child’s job is to bring entertainment to the family, usually in the form of humor.

The roles described above are the classic survival roles described by Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse (1991) in her book The Family Trap. These roles do not always follow the pattern described above, but considerably more often than not, they do. The firstborn is usually the Hero because it is the preferred role, and the child has the first crack at it. All kids want the positive attention and honor assigned to the Hero. However, if that mask is taken, then the next children have to settle for the next-best thing. The Rebel is the second most effective role. Even though the attention is negative, they get lots more of it because the parents have to deal with this child’s misbehavior, so the Rebel becomes the priority. Middle children are more like to get lost in the crowd, so they must sharpen their skills with fantasy in order to survive. These children also tend to be chameleons, switching from one survival role to another whenever the opportunity presents itself. Many times they experience all the roles in their life at one time or another. The baby of the family is almost always the center of attention so it is not surprising that these children make the most of that and become the Mascot.

So, it is birth order, not personality, not willfulness, and not inherently bad character that reinforces or “shapes” the original masks we learn to wear. Children do not decide to behave this way, they instinctively act-out these roles until they find the one that works the best in getting them the time, attention, affection and direction they need. Heroes get it from teachers, coaches, newspaper reporters, and others who are amazed by their outstanding abilities. Rebels gets it from teachers, principals, juvenile officers, counselors, and anyone else who wants to help them get back on track. The Lost Child gets it through fantasy, and the Mascot gets it through being on stage.

These roles are also reinforced at home because they all bring something to the family, helping the system to survive as well. The Hero brings honor to the family. The Rebel brings distraction, which takes the focus off the primary dysfunction in the marital pair. This is why another term used for the Rebel is “Scapegoat.” They act as a lightning rod help to keep the family intact because, if the parents have too much time to face what is going on between them, they might get a divorce, and the family then disintegrates. The Lost Child brings relief because you never have to worry about this child and hardly notice he is there. The Mascot brings entertainment and humor, diffusing the seriousness of the family dysfunction. All of these roles look different on the outside, but they are all alike on the inside.

Impression Management

Another function of the Invented Self is to manage the impressions of others that are important to us. Impression Management is driven by the “what-would-other-people-think” syndrome. It goes something like this: If I have ten people in my life who are important to me, and one of them is not happy with me while the other nine think I am the greatest thing in the world, I would focus much of my energy thinking about how I could get that one back in line with the others. If two or three get upset with me, I get anxious. If four or five of them don’t think much of me, I get disparate or panicky because it almost feels like I am dying.

It feels like I am dying because, in a way, I am. I draw my identity, my sense of self, from those ten people. Hence, I must be vigilant in managing the impressions of those around me. If they accept me and think I am okay then I must be … right? Not necessarily—even if they accept me—I cannot truly accept their acceptance because, at another level, I feel like a phony. An example of this is when we have difficulty accepting compliments from others. Somewhere inside the voice of shame is telling us “They wouldn’t say that if they really knew you!” The voice may even be inaudible, but we feel like a phony anyway. This accounts for the paradox of why we tend to discount or minimize anything positive coming from those we try to please.

The survival roles described above are examples of the masks we learn to wear in childhood. As we grow and the pain continues to accumulate, we get more and more sophisticated in the masks we wear. For a fairly complete catalog of masks read John Powell’s book (1995) Why I am afraid to tell you who I am.