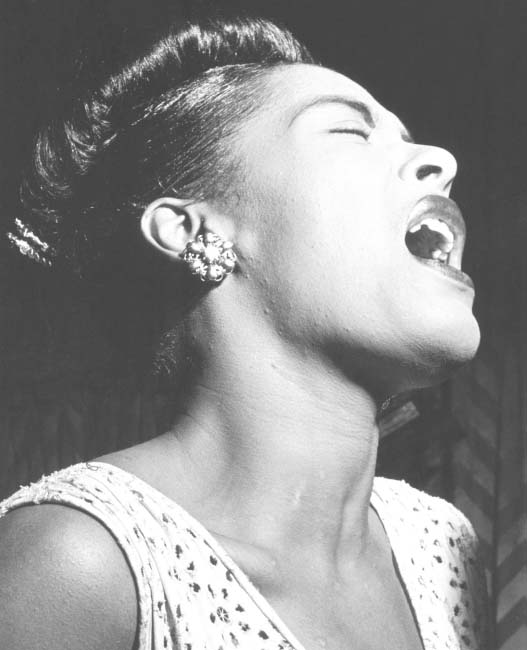

For a song that has become something of a secular hymn, it’s strange that Billie Holiday’s plaintive ‘God Bless the Child’ grew out of a row with her mother. But then, as Tony Bennett said of Holiday: ‘When you listen to her, it’s almost like an audio tape of her autobiography. She didn’t sing anything unless she lived it.’

‘God Bless the Child’ is attributed to both Holiday and Arthur Herzog Jnr, although both later claimed sole credit for it. The song was hastily written in 1939, and Holiday said she wrote it in a rage after her mother refused to give her a small loan – at a time when Holiday was bankrolling her restaurant. ‘She wouldn’t give me a cent. I was mad at her, she was mad at me … Then I said, “God bless the child that’s got his own”, and walked out’, according to her autobiography Lady Sings the Blues. The vocalist stewed for three weeks before ‘a whole damn song’ fell into place and she rushed to Greenwich Village to ask songwriter Herzog to help sort the tune out. ‘We changed the lyrics in a couple of spots, but not much,’ she wrote.

But Herzog tells a different tale, according to Donald Clarke’s biography of Holiday. Here, the still-angry singer told Herzog about the argument, and got to the part when she stormed off with the words ‘God bless the child’. Herzog interrupted with ‘What’s that mean?’ Twenty minutes later, they had a song. According to Herzog, Holiday’s only contribution, apart from the title and story, was to take one note down by a half step. Herzog found a publisher the next day, although Holiday did not record it until 1941, for the Okeh label with the Eddie Haywood Orchestra. It was a moderate hit, peaking at Number 25 in the Billboard charts. The lyrics interweave the original spat into seeming folk-mottos and biblical references. The opening lines, ‘Them that’s got shall have/Them that’s not shall lose/So the Bible says, and it still is news’, echo St Matthew’s parable of the talents: ‘For to all those who have, more will be given. …’

But as the song progresses, the lyrics shift the parable – man’s duty to make the most of what you have been given – into a different context. The line ‘Rich relations give crusts of bread and such, you can help yourself, but don’t take too much’ captures survival in an unequal world.

Holiday returned to the song several times before she died aged 44 in 1959, including with the Count Basie band in 1952 – a video clip shows her in front of the slowly swaying brass section. She sang it differently every time, altering phrasing, placement and pitch, yet creating in the listener the illusion that they were hearing each note exactly as originally written.

Jazz instrumentalists later developed the song, though it took more than a decade for the song to resurface. Sonny Rollins recorded it first as an epic ballad on the 1962 album The Bridge, and later as a soulful canter over the new rhythms of funk on the 1973 album Horn Culture. Eric Dolphy’s rippling unaccompanied reading on the 1963 Illinois Concert confirmed the bass clarinet as a jazz instrument. A sombre, soulful and brassy vocal cover was a Top 10 hit for the jazz-rock band Blood Sweat and Tears in 1969.

The best-known vocal versions tend to be from singers paying homage to Holiday. Diana Ross launched her film career capturing some of Holiday’s fragile strength in the 1972 biopic Lady Sings the Blues, and Tony Bennett duetted with the digital ghost of Holiday on the track for his 1997 tribute album Tony Bennett on Holiday. José James last year recorded a prowling blues-laced version on his Holiday songbook album Yesterday I Have the Blues.

The song was part of the soundtrack in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film Schindler’s List – jazz was banned under the Nazis, so the scene emphasized Schindler’s renunciation of the regime. Even The Simpsons slipped in some reverence on their 1990 The Simpsons Sing the Blues album, with a version that includes some tasty sax from Bleeding Gums Murphy, after Lisa Simpson demands a live band. The Moby and Oscar the Punk electronica remix was a mistake.

The song’s title has even been pulled into service in an education debate in the US about the role of charter schools. It turns up at funerals and birth celebrations alike. Like the parable, the song has prompted many interpretations.

Mike Hobart