BOONE TOLD THE SETTLERS AT BOONESBOROUGH ABOUT THE INDIAN forces being readied to attack their little fort. He said that “he was now come home to help his own people fight and they must make what preperration they could but the indeans would certainly be there in a few days.”1 There was much to be done and little time to do it. Boone told Filson that he had “found our fortress in a bad state of defence.”2 William Bailey Smith, the major who had brought fifty reinforcements to Boonesborough in the fall of 1777, put Boone in charge of restoring the defenses. One of the palisade walls had fallen down almost completely and had to be rebuilt. The gates and posterns were strengthened. At the southeastern and southwestern corners new bastions, or blockhouses, were built, two stories high, with the second story projecting out over the first and with openings left in the floor to permit defenders to fire on attackers who came close to the walls. (“What is meant by a block house?” Daniel Trabue wrote, describing the ones at Logan’s Station at this time, and then answered his own question: “The upper story to be much biger than the lower story and to Jut over so that you may be up on the upper floor and shoot Down if the indeans was to come up to the walls, and they cannot climb up the walls of these houses.”)3 Because the old well inside the fort did not give much water, work was started on digging another one. Women cast lead into bullets, smoothed the mold marks off the cast bullets, and prepared bandages. Brush around the fort was cut down.4

Boonesborough asked the neighboring settlements for reinforcements. Men were scarce. The small settlements had been further depleted by supplying men to George Rogers Clark on his bold expedition to take the fight west to the British by attacking the British stations at Kaskaskia and Cahokia in Illinois and Vincennes along the Wabash in Indiana. Clark had realized that “if the Indians destroyed Kentucky they’d attack our frontiers—obliging the states to keep large bodies of troops for their defense” and, as he knew that “the commandant [Henry Hamilton] of the different towns of the Illinois country and the Wabash was busily engaged in exciting the Indians against us, their reduction became [Clark’s] first object.”5 Aided by Kentucky riflemen, Clark was able to capture Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in the summer of 1778 and, after the British retook Vincennes in December 1778, to take it again in February 1779.

Despite the depletion of their own ranks, however, Logan’s Station sent about fifteen men, and Harrodsburg a few, to buttress Boonesborough.6 To increase the firepower “arms and ammunition were given to the Negro men” in the fort, and any “well-grown boy became a fort soldier, and had his port-hole assigned him.”7 Still, there were not many rifle bearers in Boonesborough—perhaps sixty, as against the more than four hundred Indians who were about to attack them.

One more rifle bearer joined the Boonesborough settlers on July 17—William Hancock, one of the captive salt-boilers, who had been adopted by Captain Will, the Indian who had taken Daniel Boone captive when Boone was hunting in Kentucky in 1769. To prevent Hancock from escaping, Captain Will had Hancock sleep naked, while Captain Will slept with his head on the doorway to block the way out. Hancock waited until a night when Captain Will had drunk too much rum. That enabled the unclothed Hancock to flee his soddenly sleeping adoptive father. Carrying with him only three pints of raw corn, Hancock rode a stolen horse to the Ohio, swam across the river, and made it to Boonesborough nine days after he left Captain Will. He arrived at the fort, still naked, so weak that he had to be carried inside. Hancock reported that the Indians were coming four hundred strong and intended, if the settlers declined to come over to the British, to batter down the fort with four swivel guns that the British were providing to them from Detroit.8 That was a scary prospect: the fort’s frail palisade could not withstand pounding even from light artillery. The only good news in Hancock’s report was that Boone’s escape had caused the Indians to postpone their expedition into Kentucky for three weeks so they could send runners to Detroit for instructions and militia reinforcements.

Hearing Hancock’s report, Boone wrote to Col. Arthur Campbell, commander of the Fincastle County militia, asking for reinforcements: “If men can be sent to us in five or six weeks, it would be of infinite service, as we shall lay up provisions for a siege.”9 Colonel Campbell, unwilling to act on his own, sought authorization from Virginia’s Executive Council, which was thoroughly absorbed by the fighting with the British and the Tories in the east. Not until early September did relief start on its way from Virginia. The relievers showed up at Boonesborough long after the siege was over.10

The Indians, fortunately, were slow to act in launching their attack. Boonesborough’s settlers had time in August to lay in most of the corn harvest. At the end of the month Boone took a step that has been a puzzle ever since: he took twenty or thirty men—close to half the fort’s fighting strength—for a raid on a Shawnee village called Paint Creek, across the Ohio on the Scioto River. Boone said that “these indians was rich in good horses and beaver fur,” so the Boonesborough party “could go and make a great speck and Git back in good time to oppose the big army of Indians.” Col. Richard Callaway “apposed the plan with all his might but they went.”11

Boone’s men crossed the Ohio and headed for the Paint Creek village. Simon Kenton, scouting ahead of the group, stumbled into a party of Indians heading south toward Boonesborough. A firefight broke out. Kenton killed and scalped one Indian. Two Indians were wounded. There were no settler casualties. Kenton went on ahead and reported that the Indians had left Paint Creek, evidently as part of the large expedition against Boonesborough. Boone and the others turned back south and saw signs that hundreds of Indians had crossed the Ohio and were on the Warrior’s Path, heading to Boonesborough. Only by leaving the trail and going through the woods were Boone and his raiders able to bypass the much larger Indian force and get back to Boonesborough before the Indians got there. Boone and his men arrived at the fort on the evening of Sunday, September 6, 1778, and told the settlers that the Indians were at hand and the siege would likely start the next morning.12

It is hard to justify Boone’s Paint Creek raid. Was it to gain intelligence about the Indians’ planned attack? Boone’s information on these subjects was somewhat stale, dating back to his escape in late June. Hancock’s information was only slightly more recent, because he had escaped in mid-July. Was it to bring home to the Indians their own vulnerability and so dissuade them from their planned attack on Boonesborough? But Boone’s raid did little more than Andrew Johnson’s raid had done to show the Indians that the whites now knew the way to the Shawnee villages. Moreover, a raid by twenty or thirty settlers was hardly likely to cause four hundred warriors to stop in their tracks. Was the raid intended to show the men at Boonesborough that Boone was on their side and was willing to fight the Indians? There was some morale boost from the raid; a Williamsburg paper reported, “Captain Boone, the famous partisan, has lately crossed the Ohio with a small detachment of men, and nearing the Shawanese towns, repulsed a party of the enemy, and brought in one scalp, without any loss on his side.”13 Did Boone seek to renew the men’s liking for him by enabling them to get plunder from a quick raid, including horses that the Boonesborough settlers needed badly? Perhaps. Boone knew how much the Boonesborough settlers liked a “good speck” and the chance for booty.

But all these possible benefits, even taken together, were small relative to the raid’s risks. The Paint Creek raid took away manpower badly needed to strengthen Boonesborough’s defenses. It also carried the risk that many who went on the raid would be killed or captured and so would not be able to shoulder rifles in the fort’s defense. The word rash comes to mind as well as the one caveat about Boone noted by Felix Walker, the young axeman whom Boone had nursed back to health after the Indian attack on Boone’s trailblazers in March 1775: Boone “appeared void of fear and of consequence—too little caution for the enterprise.”14 In the event, however, Boone and the raiding party had managed to make it back safely to the fort. The Boonesborough settlers had only one night before the Indians would be there. The settlers readied their guns, molded and trimmed more bullets, brought in vegetables from the fields, and fetched water.

The next morning the Indians appeared before the fort—hundreds of them. Squire Boone’s boys, Moses and Isaiah, who had been out watering horses, started to ride out to meet them, thinking the arrivals were the longed-for reinforcements from Virginia. Boone yelled at his nephews to get back in the fort. Boone and the other scouts followed, and the fort gate was closed and barred.

The attackers rode in front of the fort, just out of range of the fort’s rifles. They rode single file, which made them look even more numerous than they were, but there were plenty of them. Boone said there were 444 Indians. The Indians—mostly Shawnees but with some Cherokees, Wyandots, and others—were in full war paint. There was also a French-Canadian officer and eleven other French Canadians with him, the troop of militia that Hamilton had sent from Detroit. The parading riders bore British and French flags. The men inside Boonesborough—about 60 in all—were outnumbered more than 7 to 1.15 To the defenders the only good to be seen in the attackers’ show of strength was the absence of swivel guns, the light cannon William Hancock had heard would be sent from Detroit to enable the attackers to batter the fort.

Pompey—the black man living among the Shawnees who had acted as an interpreter when the Shawnees captured Boone in February 1778—came close enough to the fort to be able to call out Boone’s name. Boone called back to him. Pompey cried out that Blackfish had come to accept the surrender of the fort—which Boone had promised. He told Boone that Blackfish was carrying letters from Governor Hamilton promising safe conduct for everyone. A voice called out from the Indians, farther away from the fort: “Sheltowee!” It was Blackfish, the war chief, Boone’s adoptive father. Boone went outside the fort to a stump about sixty yards from the fort, within range of the defenders’ rifles, to meet with Blackfish and Moluntha, Cornstalk’s successor as the Shawnees’ head chief.

“Howdy, my son,” Blackfish said—reaching out his hand. “Howdy, my father,” Boone replied, shaking Blackfish’s hand. Boone had enough Shawnee and Blackfish enough English that they could communicate a bit without an interpreter. “What made you run away from me?” Blackfish asked. “I wanted to see my wife and my children.” “If you had asked me,” Blackfish said, “I’d have let you come.”16

Moluntha broke in. “You killed my son the other day, across the Ohio River,” he said. So the Indian that Simon Kenton had killed and scalped on the Paint Creek raid was Moluntha’s son? That was not going to make things easier. Boone said he had not been there. That was not true, and Moluntha knew it. “It was you,” Moluntha said. “I tracked you here.”

Blackfish handed Boone the letters from Hamilton. The letters reminded Boone of his pledge to cause the fort to surrender. If the settlers surrendered, they would be given safe conduct to Detroit. Officers who came over to the British side would be kept at their present rank. If the settlers resisted, Hamilton said he could not be held responsible for the bloodshed that would result.17 Blackfish also produced a wampum belt with red, white, and black rows of beads. The belt, Blackfish said, showed the path from Detroit to Boonesborough and the ways it could be traveled. Red was the path of war, the way they had come to Boonesborough. White was the path of peace, the path they would go back on together if Boone and the others surrendered peaceably. Black was death. Black was the death that would happen if they did not surrender.18 Blackfish asked Boone what he thought about the letters and the belt—which, he wanted to know, would Boone choose?

Boone said there was much to consider, and he needed to consult with his colleagues, including the officers who had come to the fort since his capture. Blackfish said he understood. He let on that his warriors were hungry. Boone, knowing that the Indians could take whatever they wanted without his blessing, said, “You see plenty of cattle and corn; take what you need, but don’t let any be wasted.” Blackfish in turn presented Boone with “a gift for your women”—seven smoked buffalo tongues. The men smoked together, and Boone returned to the fort with Blackfish’s present.

Inside the fort the leaders looked at the letters from Hamilton. To Colonel Callaway the letters, with their references to what Boone had said he would do to encourage the surrender of Boonesborough, were further proof that Boone had agreed to betray the fort. Boone said he had led Hamilton to believe that he would do so, but only as a way of being able to get back to defend Boonesborough. Boone told the Boonesborough settlers that he was prepared to fight, but he also said he thought “they could make a good peace with the Indians,” and if people decided to surrender, he would be compelled to go along with the decision of the majority.19

There was plenty to think about. As Filson recorded Boone’s thoughts a few years later, there was, in Filson’s florid words, “a powerful army before our walls, whose appearance proclaimed inevitable death, fearfully painted, and marking their footsteps with desolation,” and “if taken by storm we must inevitably be devoted to destruction.”20 This was not like any earlier attack on a station in Kentucky. Instead of a handful of Indians content to lurk near the fort and pick off hunters and stragglers, but without the strength to mount an all-out attack, this was a well-armed force of hundreds, accompanied by French-Canadian soldiers who presumably knew how to conduct a siege.

Young John Gass thought Boone laid out the choice carefully for the settlers so that Boone would be “free from blame should they hold on and the Indians overcome them.”21 It is also possible that Boone was simply being a realist and that he saw the call as a close one, given the extent to which the attackers outnumbered the defenders. Another settler who was a boy at the time remembered that there had been a great difference of opinion, “half of the men willing to surrender, and the other half ready to fight, and rather die” than surrender.22

After some back-and-forth Col. Richard Callaway, the fort’s commanding officer, “swore he would kill the first man who proposed surrender.”23 That doubtless shortened the discussion. Maj. William Bailey Smith, second in command, chimed in that they should “refuse the offer and defend the fort.”24 Squire Boone said “he would never give up” but “would fight till he died.” All the men favored resistance. “Well, well,” Boone said, “I’ll die with the rest.”25 So the decision was to fight—but it made sense to continue to stall as long as possible, in the hope that reinforcements would finally arrive from Virginia. Boone and Smith, who were appointed to talk further with Blackfish, agreed to meet with the Indian leaders late that afternoon.

Blackfish was accompanied by Moluntha and a few other Indians. Panther skins were spread out on logs for the speakers to sit on. Major Smith wore full military regalia, including a scarlet coat and a macaroni hat with an ostrich feather in it, perhaps to make an impression and to support what Boone had said about the need to consult with new officers at the fort.26 After hand shaking, introductions, and pipe smoking, Blackfish asked Smith and Boone their views of the surrender offer. It was a kind offer, Smith said, but the trip would be hard for the women and children. “I have brought forty horses and mares for the old people and women and children to ride,” Blackfish said. “I am come to take you away easy.”27 Boone said they needed more time to discuss it because there were many chiefs to consult. Blackfish agreed to one more day of talking, but Boone came away from the meeting convinced that they would not be able to stall any longer.

One heartening thing from the palaver was the Indians’ belief, evidenced by the number of extra horses they said they had brought, that there were forty women and children in the fort—not a dozen or twenty. Given the usual ratio of men to women and children in the frontier forts, if the Indians thought there were forty women and children in Boonesborough, they must have thought there were least a hundred men there—not sixty. In fact, the Indians had overestimated the number of rifle-bearing men in the fort—partly because an American captive in Detroit had misled Hamilton into thinking that two hundred reinforcements from Virginia had already arrived at the Kentucky forts. The Boonesborough defenders worked to strengthen that misconception. While the men were visible on the stockade walls, the women put on men’s hats and hunting shirts and marched back and forth inside the fort with the gate open so the Indians could see their numbers.28

As had been agreed with Blackfish, the women were also allowed to go out to the spring to get water. It was uneasy work, hauling water within easy rifle range of the Indians. The water bearers must have regretted the absence of a sufficient well inside the stockade. “Fine squaws,” the Indians called as the women drew and hauled water.29 At midday the Indians made an unusual request: the Indians had heard how pretty Boone’s daughter was, and they asked that she please be brought to the gate so they could see her and the other squaws. Maybe the Indians had heard from Hanging Maw or others who took Jemima and the Callaway girls captive in 1776 about the girls’ beauty. To buy more time, Boone agreed. Jemima and one or two other women came to the open gate, accompanied by riflemen, as Blackfish and several warriors looked on. The Indians made signs that the white women should let down their hair. They “took their Combs out,” according to Jemima’s daughter, “and let their hair flow over their shoulders.”30 The Indians nodded their approval and left.

Toward evening Pompey called out that it was time to talk again about the surrender. Pompey’s officiousness as an interpreter was grating on the Boonesborough defenders, many of whom were slaveholders from Virginia and North Carolina. Boone, Smith, and others met with Blackfish and other Shawnee leaders and delivered the settlers’ conclusion: “We were determined to defend our fort while a man was living.”31

Blackfish seemed surprised by the reply. After a time Blackfish said the Indians’ orders “from Governor Hamilton [were] to take us captives, and not destroy us, but if nine of us would come out, and treat with them, they would immediatly withdraw their forces from our walls, and return home peaceably. This sounded grateful in our ears; and we agreed to the proposal.” Both sides agreed to get together again the following day. Blackfish said that “he had many chiefs from many different towns with him and that all would have to participate in the treaty.” That apparently sounded a little fishy to Boone, who said “there were so many officers in the fort… and that they all would have to participate in the treaty.”32

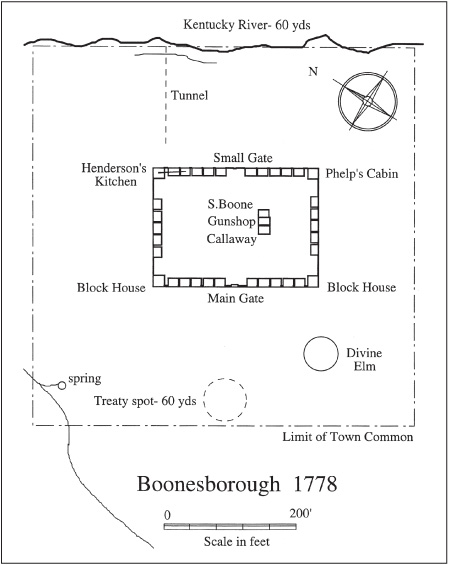

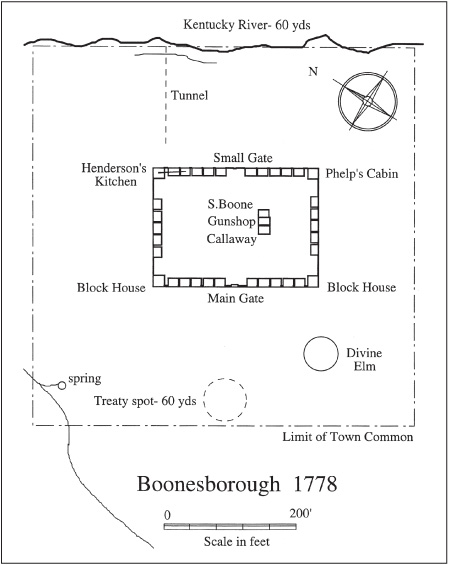

On the morning of Wednesday, September 9, 1778, the women of Boonesborough laid out in front of the fort a big meal for the Indians—venison, buffalo tongue, cheese, milk, corn—in an effort to show the attackers that the defenders had plenty of food, more than enough to outlast a long siege. After the meal the Americans walked to the meeting ground, within sixty yards—that is, well within rifle range—of the fort. The Americans included Boone, Col. Richard Callaway, Maj. William Bailey Smith, Squire Boone, Flanders Callaway, Isaac Crabtree, and several other leading settlers. Riflemen were placed in the corner bastions of the fort, with orders to keep their guns trained on the Indians and to shoot at the first sign of trouble. Boone told the riflemen not to wait for fear of hitting him and the others but to “fire at the lump”; “fire among the crowd; as the Indians were most numerous, they were most likely be the sufferers.”33

The Indians at the meeting ground far outnumbered the whites. Boone saw many strong young warriors at the meeting place, in addition to Blackfish and the elders. “These are not chiefs,” Boone said. Blackfish sent the young men away, but the Indians still outnumbered the whites two to one and seated themselves with an Indian on either side of each settler. What Boone did not see was that, just as the settlers had riflemen poised in the bastions of the fort, Indian riflemen were covering the meeting from brush in a nearby hollow lined with sycamore trees. The discussions began in earnest after the peace pipe was passed around. Blackfish initially proposed that the Indians would agree to make peace if all whites agreed to pull out of Kentucky entirely in six weeks. The Americans said they could not agree to this. “Brothers,” Blackfish said, “by what right did you settle in this country?” Boone said the country had been purchased from the Cherokees. Blackfish asked a Cherokee who was there if that was true. The Cherokee confirmed it.34

Blackfish then proposed that his army would go home if both sides would recognize the Ohio River as the boundary between their settlements, though each could hunt and trade on either side of the river. There appears to have been another important provision in Blackfish’s proposal, one mentioned by Boone late in his life, though understandably not told to Filson: the settlers had to pledge allegiance to the British Crown and submit to the authority of Lieutenant Governor Hamilton at Detroit.35 The settlers’ leaders agreed to these terms, and, as Boone told Filson, “the articles were agreed to and signed.”36

Did this mean that the Boonesborough leaders—including Colonel Callaway, who had vowed to shoot the first settler who proposed surrender—actually agreed to go over to the British side, in the middle of the American Revolution? And if they made such an agreement, did they intend to honor it? It is much more likely, given their previous and subsequent fighting against the British and their Indian allies, that the Boonesborough men were willing to misrepresent their intentions, as Boone had done to Hamilton at Detroit, in order to be able to fight another day and to buy time for the arrival of the promised reinforcements from Virginia.

The signed articles have not survived, and the oral agreement they purported to reflect vanished within minutes. After Blackfish declaimed in Shawnee to his warriors, who were some distance away from the meeting place, he turned back to the white representatives. Among us it is customary, he said, when concluding a treaty intended to be lasting, “to shake long hands,” with two Shawnees shaking hands with each of the men with Boone—to bring their hearts close together. “We agreed to this also,” Boone told Filson, “but were soon convinced their policy was to take us prisoners.—They grappled us; but, although surrounded by hundreds of savages, we extricated ourselves from them.”37 It may be that, as Daniel Trabue reported, Colonel Callaway “was the first that Jirked away from” the Indians, triggering shots from the bastions. It may be that Indians fired at the whites from the sycamore hollow. It may also be that some of the whites outside the fort, in thinking the Indians were trying to seize them, misunderstood what was in fact a customary Indian way of sealing an agreement by locking arms, and in doing so brought on a fight that could have been avoided. What is clear is that a melee broke out—a “dredful skuffil,” in Trabue’s words.38 Boone threw his adoptive father Blackfish to the ground hard. The Indian who had passed around the pipe tomahawk before the discussions tried to hit Boone with it but managed only to gash the skin on the back of Boone’s head with the handle. The wound, more than two inches long, left a scar over which hair never grew.39

Boonesborough at the Time of the Siege in 1778. After a sketch by Moses Boone. Shows where the “treaty” was held, sixty yards in front of the main gate.

Courtesy of Neal O. Hammon

The whites ran for the fort. Several Indians were hit in the first volley from the bastions. One rifleman posted in the southwest bastion of the fort had his rifle trained on an Indian sitting behind the treaty council, wearing brooches, half-moons, and other silver ornaments. “That’s a fine mark,” the rifleman thought—and pulled the trigger as soon as the shooting started, killing the Indian.40 Squire Boone was shot, the ball grazing one shoulder and the backbone and lodging in the other shoulder. The shot knocked him down, but he got back up and made it into the fort.

The time for pipe smoking and treaty making was over. The attackers were pouring fire into the fort, and the defenders were firing back. Squire Boone picked up a rifle and fired at an Indian from his assigned post in the southwest bastion. In reloading, he found his shoulder hurt so much from his wound that he could not ram the ball home. His wife looked at the wound and pronounced it a slight one—but the pain in Squire Boone’s shoulder grew worse. When the Indian fire slackened, Daniel Boone made a deep cut and dug out the ball, which had been lodged in his brother’s shoulder bone. Squire Boone took to his bed, keeping beside him a light broadaxe that he said he would use if the Indians made it into the fort.41

The Indians rushed the fort that afternoon but were driven back by fire from the bastions. Inside the fort many of the women and children huddled in Colonel Callaway’s cabin in the center of the yard. The noise was deafening—the gunfire, the whooping and screaming of attackers and defenders, the barking of the fort dogs, the panicked cattle and horses milling around the yard.42 As Moses Boone, who was only ten years old at the time, remembered it, “The women cried and screamed, expecting the fort would be stormed.”43 Elizabeth Callaway, one of the girls who had been captured by the Indians in 1776, found one of the settlers under a bed in the cabin and drove him out with a broomstick. The man was a German named Matthias Prock. “I was never made for a fighter,” Prock said. “I was made for a potter.”44 Boone and Callaway set him to work digging the new well deeper.

Jemima Boone loaded guns, carried ammunition, and ran from cabin to cabin with food and water. Coming into a doorway, she felt as if she had been slapped on her backside. She had been hit by a bullet in what Boone’s daughter-in-law euphemistically described as “the fleshy part of her back.” Fortunately, the bullet was spent and did not make it through her petticoat but instead drove the cloth into her flesh. When she tugged at her clothes, the bullet fell out.45 The defenders realized that the attackers could look down and fire into the center of the fort from hills on either side, even though the hills on the far side of the river were more than two hundred yards away and the hills on the same side were over three hundred yards away—long shots but just barely feasible if rifles were heavily charged with powder.46 The Boonesborough defenders opened holes in the walls of adjoining cabins so that the settlers could move from cabin to cabin in shelter, without being exposed to the attackers’ fire.

For nine days and nights the attacks continued. The settlers had limited ammunition, and the women “used to gather the Spent Balls at night to mold up to fight the Enemy next day.”47 Beginning with the second night, the Indians, not being able to take the fort by rifle fire during the day, attempted to torch the fort at night—using tactics that had enabled Indians to capture forts during the Seven Years’ War and Pontiac’s War.48 They set fire to flax drying alongside the stockade wall. John Holder, Colonel Callaway’s son-in-law, ran out the fort’s gate, doused the fire with water, put the fire out, and ran back inside, while bullets splattered around him. Holder was a swearing man.49 As the Indians shot at Holder, he cursed them creatively. When Holder made it back inside the fort, glad to be still alive, his mother-in-law, Mrs. Callaway, suggested, “It would be more becoming to pray than to swear.” “I don’t have time to pray, goddammit,” Holder thundered.50 It was a phrase the defenders found pleasure in repeating.

The Indians kept coming at night, aiming to throw on the cabin roofs torches made of shellbark, hickory bark, splints, flax, and black powder, all tied around a stick for a handle. Many of the burning torches fell into the central yard of the fort, where they did no harm. Some torches fell on the roofs—but most of the roofs sloped inward toward the courtyards, and the women managed to pull off any burning shingles with long poles. Squire Boone also improvised water-filled squirt guns made out of old musket barrels with pistons in them. The squirt guns, squirting up to a quart of water, worked well against the rooftop fires. The torches did little harm to the fort but lit up their bearers on the way in, making the Indians who carried them prime targets for the fort’s defenders. Many torch-bearing Indians were wounded or killed.

Squire Boone came up with another invention: a wooden cannon, made of two sections of black gum tree banded together with iron. The first firing of the jerry-built cannon, loaded with a swivel ball and some twenty leaden bullets, broke up a crowd of Indians perhaps two hundred yards from the fort. “O Lord, how I made the Indians fly,” was how Squire Boone remembered it. The noise itself was formidable. On the second firing, however, the cannon burst, which the Indians found funny. “Fire your damned cannon again!” they called out.51

On Friday, September 11, the firing died down some. The defenders heard a new sound, a sound of chopping and digging, coming from the rear of the fort, the side that ran parallel to the Kentucky River. The riverbank was about sixty yards away from the fort. The defenders saw muddiness in the river water near where the sound was coming from. They suspected that the Indians were digging a tunnel to the fort—perhaps to blow it up, perhaps to give the attackers a safe passage into the fort. Boone and the other defenders started a countermine, or trench, under the rear wall of the fort, across the tunnel’s likely course.52

For all the shooting only two Americans were killed during the siege, both on the night of Friday, September 11. One was a slave named London, a valued rifleman. London had dug out under a cabin to push away a fire that had been set in a fence adjoining the cabin. Spotting an armed Indian crouched behind a tree stump near the fort, London asked the men in the cabin for a loaded rifle. He aimed at the Indian and fired, but the striking flint lit only the powder in the pan of his rifle. The flash in the pan gave away his position. The Indian fired, hitting London in the neck and killing him.

The other defender who was killed was a German American named David Bundrin, who was looking out a stone-lined porthole in the southwest bastion when an incoming bullet hit a stone next to the porthole and split. Half of the bullet penetrated Bundrin’s forehead. His brain ran out of the wound as he rocked back and forth, his elbow on his knee in a sitting posture, never saying a word, sometimes wiping the oozing brains with his hand. Bundrin’s wife did not realize how badly he had been hurt. Until he died, she kept saying it was God’s blessing he had not been hit in the eye.53

For the next six days and nights the fighting went on—the Indians firing into the fort, the defenders shooting back; the Indians’ trying to torch the fort at night; the mining and countermining. During much of the siege the fighters yelled insults at each other. The Shawnees’ trade English was up to the exchange. “What are you doing down there?” the defenders called out. “Digging a hole; blow you all to hell that night, may be so!” the Indians called. The defenders called back, “Dig on—we’ll dig and meet you—we’ll make a hole to bury five hundred of you yellow sons of bitches!”54 One Indian delivered a nonverbal insult by climbing up a tree at what he believed to be a safe distance from the fort. On his perch he lifted his breechclout, “turned the insulting part of his body to the besieged and defiantly patted it.” One of the recurring stories of the Boonesborough siege is that a defending rifleman took a large-bore rifle, loaded it with extra powder, fired, and brought down the distant Indian.55

As the defenders dug their countermine under the rear wall of the fort, John Holder and some of the other riflemen hurled unearthed stones over the stockade to roll down toward the tunneling Indians. “Come out and fight like men,” the Indians called out, “don’t try to kill us with stones, like children!” One of the older women in the fort, a woman named Mrs. South, told the defenders “not to throw stones at the Indians, for they might hurt them, make them mad, and then they would seek revenge.”56 That became a byword among the defenders—O, don’t do that, you might hurt the Indians and make them mad, and then they might try to hurt us in revenge.

Pompey, the black interpreter, popped up repeatedly from the cover of the riverbank to fire both bullets and insults at the defenders. Eventually, he was shot and fell back out of sight behind the bank. He was not heard from again. “Where’s Pompey?” the Americans yelled. At first the Indians called back, “Pompey ne-pan”—Pompey’s sleeping—but eventually they called out, “Pompey ne-poo”—Pompey’s dead.57

On the night of Thursday, September 17, the Indians launched their most massive attack. Firing on both sides was continuous. Between the flashing gunpowder, the torches carried and hurled by the Indians, and the fires on the cabin roofs started by the torches, Moses Boone remembered that “it was so light in the fort that any article could be plainly seen to be picked up, even to a pin.”58 Another witness to the attack, William Patton, was a Boonesborough resident who had come back after a long hunt only to find the fort besieged by hundreds of Indians. Watching the siege from a hiding place outside the fort, Patton saw that “the Indians made in the night a Dread-full attack on the fort. They run up to the fort—a large number of them—with large fire brands or torches and made the dreadfullest screams and hollowing that could be imagind.” Without waiting for more, Patton ran from the scene to Logan’s Station, where he reported that the Indians had taken Boonesborough by storm and that he had “heard the woman and Children and men also screaming when the indeans was killing them.”59

But Boonesborough had not been taken. There had indeed been many torches and fires carried by the attackers that night—but they lit up the Indians so that the Boonesborough men could shoot them. More Indians were killed that night than in the whole rest of the siege. The weather also helped. It poured rain, which helped put out the fires on the cabin roofs and caused the Indians’ tunnel to collapse. When morning broke on Friday, September 18, no Indians were to be seen. Settlers cautiously went out to fetch cabbages to feed the cattle that had been penned up in the fort during the siege. The cattle “could scarcely low,” they “were so nigh famished for want of water.”60 Other defenders gathered the lead that the Indians had shot into the logs of the bastions and walls of the fort, so it could be refashioned into bullets. At the riverbank the settlers found the entrance to the tunnel the Indians had been digging and followed it in from the river fully forty yards—two-thirds of the way to the fort, until they were blocked where the water-sodden roof had collapsed. A British official later told Simon Kenton, when Kenton was a British prisoner, that the tunnel collapse caused the Indians to quit.61

Boone later summarized to Filson the outcome: “During this dreadful siege, which threatened death in every form, we had two men killed, and four wounded, besides a number of cattle. We killed of the enemy thirty-seven, and wounded a great number. After they were gone, we picked up one hundred and twenty-seven pounds weight of bullets, besides what stuck in the logs of our fort; which is certainly a great proof of their industry.”62 Boone’s next sentence elides the next twelve months, as if nothing worth mentioning happened in that time: “Soon after this, I went into the settlement, and nothing worthy of a place in this account passed in my affairs for some time.” In fact, much happened during that year—including an event Boone must have found so humiliating that he wanted no record of it: his own court-martial.

Boone described the siege and its outcome in a letter he wrote to Rebecca, who was still back on the Yadkin with her Bryan kin. In addition to saying he looked forward to rejoining her and the children, Boone mentioned allegations that he was a Tory and had taken an oath of allegiance to the British at Detroit. As to the British, Boone wrote, “God damn them, they had set the Indians on us.” The letter has not survived; Rebecca destroyed it, perhaps because of Boone’s uncharacteristic use of profanity, perhaps because of the reference to the court-martial. But Rebecca showed the letter to Bryan relatives, who remembered both the mention of the impending court-martial and Boone’s cursing of the British. Boone’s nephew said, “Boone was very little addicted to profanity,” and remembered that Rebecca had cut the oath out of the letter with some scissors.63

The only surviving record of Boone’s court-martial is a short account written in 1827, almost fifty years after the siege, by Daniel Trabue, who was a young settler, eighteen years old, at Logan’s Station during the trial. As Trabue remembered it, Colonel Callaway charged that Boone “was in favour of the britesh” and “ought to be broak of his commission.” Callaway said that Boone had led the Indians to the salt-boilers and caused the captives to be taken to Detroit “against their consent” and at Detroit “did Bargan with the British Commander that he would give up all the people at Boonesborough, and that they should be protected at Detroyt and live under British Jurisdiction.” Callaway also said that when Boone came back to Boonesborough, he encouraged men to go with him across the Ohio [the raid on Paint Creek], and they returned only hours before the Indian attackers arrived. Finally, Callaway claimed that Boone took all the Boonesborough officers to the Indian camp, out of sight of (and rifle protection from) the fort.

According to Trabue, Boone said he gave up the salt-boilers because he thought he had had to “use some stratigem” to prevent the Indians from going ahead with their plan to take Boonesborough, which was “in bad order” at the time, so Boone said the Indians would need to come back in the summer with more warriors. He said that “he Did tell the Britesh officers he would be friendly to them and try to give up Boonesborough but that he was a trying to fool them.”64

The court-martial acquitted Boone. At the same time, Boone was promoted from captain to major in the militia. The settlers had seen Boone in action in defending Boonesborough. The court’s decision showed that the men trusted Boone and his leadership and believed Boone when he said that his promises to help to cause Boonesborough to surrender had been made to save the lives of the salt-boilers and of the Boonesborough settlers. Most of the salt-boilers, when they came back to Kentucky, were to say that Boone, by agreeing to their capture, had saved their lives and the lives of those at Boonesborough.65 On Boone’s willingness to negotiate with the Indians besieging Boonesborough, Simon Kenton noted that the negotiation was an effort to gain time for relief to arrive and declared emphatically, “They may say what they please of Daniel Boone, he acted with wisdom in that matter.”66 But the very fact of the charges galled Boone. Soon after the decision, he left for North Carolina, taking with him Jemima, her husband, Flanders Callaway, and his son-in-law William Hays.

Richard Callaway stayed at Boonesborough. Reportedly, he never spoke to Boone again. Callaway did not have long to live. He managed to get the Virginia Assembly to appoint him as one of two commissioners in charge of a major improvement in the Wilderness Road that Boone had blazed—an appointment that must have been satisfying to Callaway (who had resented Boone’s leadership of the 1775 road-blazing expedition) and galling to Boone.67 But Callaway was killed before he could start to work on the Wilderness Road project. In October 1779 he had obtained a license to operate a toll ferry across the Kentucky River near Boonesborough. In March 1780, not far from Boonesborough, Callaway’s body was found scalped, stripped naked and rolled in a mudhole near where he and another man (also killed and scalped) had been building a ferryboat. His head bones had been hacked into pieces no bigger than a man’s hand. A man who saw Callaway’s body said he was “the worst barbecued man he ever saw.”68 Days later Joseph Jackson, one of the salt-boilers who had been adopted by the Shawnees, saw a scalp stretched and drying near a campfire in the Indian town where he was living and recognized the scalp as Callaway’s “by the long black and grey mixed hair.”69 Callaway’s dislike and distrust of Boone, though rejected by the court-martial, was passed on to at least one of his descendants, who years later—pointing to Boone’s repeated meetings with the Indians during the siege—said that “if it hadn’t been for Col. Callaway, the fort [Boonesborough] would have been surrendered” and that “Boone was willing, & wished, to surrender.”70

Boone had gone back to the Yadkin by early November 1778. He did not start back to Kentucky until September 1779. Part of the intervening time was spent recruiting Bryans, Boones, and other Yadkin neighbors to make the trip, but part may also have been spent convincing Rebecca to come to Kentucky, despite the squalor and danger of the Kentucky stations, rather than stay in North Carolina. Boone was deliberately elliptical about this period in his life with Rebecca, saying only (in Filson’s telling): “The history of my going home, and returning with my family, forms a series of difficulties, an account of which would swell a volume, and being foreign to my purpose, I shall purposely omit them.”71 It stands to reason, however, that Daniel would have had trouble convincing Rebecca to return to a land marked by a substantial risk of death or captivity at the hands of the Indians and by the certainty of hardship and privation.

Yet Rebecca did decide to come back to Kentucky in 1779. It must have helped that so many other Bryans and Boones were coming. Land was available for purchase at reasonable rates. Land claims based on grants from Virginia had become less chancy, with the repudiation of the Transylvania Company’s claims, the recognition of Kentucky as a county of Virginia, and the American successes against the British in the Revolutionary War. Moreover, in May 1779 the Virginia legislature had passed a law for granting land in Kentucky, spelling out comprehensible ways of claiming “waste or unappropriated lands upon the western water” based on settlement or preemption, and a procedure for buying from Virginia (initially at a price of £40 per hundred acres) treasury warrants for the purchase of the unclaimed land.72 Virginia also had appointed a commission to go to Kentucky to resolve conflicting land claims in that county. The commissioners worked hard and settled thousands of claims—and managed to award themselves some land in the process.73 Within a year of the act’s effective date Virginia had sold warrants redeemable for over 1.9 million acres—more than 7 percent of the total area of Kentucky.74 Greater certainty of title helped to encourage settlement. It is also likely that some Yadkin settlers, including some of Rebecca’s Bryan relatives, decided to come to Kentucky because they were Tories, who saw the imminence of bloody fighting between rebels and British sympathizers in North Carolina and felt they would be safer in Kentucky. One non-Tory settler said that all the settlers coming from Carolina were Tories who “had been treated so bad there, they had to run off, or do worse.”75

Fully one hundred emigrants left the Yadkin with Boone in September 1779. They were joined by emigrants from Virginia, including Abraham Lincoln, the grandfather of the future president. It was one of the largest groups to come to Kentucky through the Cumberland Gap. At about the same time settlers were coming into Kentucky from Pennsylvania down the Ohio River. The river trip was still hazardous. Indians continued to attack boats on the river, in several cases first forcing white captives to call out for help from the riverbank, so as to lure boats within rifle range. But the risk of attack on the river was somewhat reduced by the protection of a fort that Col. George Rogers Clark had built near the Falls of the Ohio and later by an armed boat that he had patrolling the river, starting in 1782.76

Boone’s group was a significant part of the increased flow of immigration into Kentucky that began in 1779. The successful defense of Boonesborough encouraged that immigration, as did Clark’s astounding victories over the British to the north and west. When Clark, then only in his mid-twenties, with barely two hundred troops, recaptured Vincennes in February 1779, he also captured Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton himself.77 Clark’s ability to beat the British and to seize the “Hair-Buyer General” shook the western tribes’ loyalty to the British cause, even though Clark was not able to muster the number of American troops he needed to take Detroit, which continued to arm Indians attacking the American frontier settlements.78

The expanding flow of settlers into Kentucky in 1779 was also encouraged by the success of an American raid on the Shawnee villages in retaliation for the siege of Boonesborough and by the movement of many Shawnees out of Ohio. In May 1779 Col. John Bowman led about three hundred Americans across the Ohio to attack Shawnee villages on the Little Miami, including a dawn assault on Old Chillicothe. In the opening volley of that attack an American bullet ripped open Blackfish’s leg from knee to thigh. The Shawnee warriors took shelter in the town’s central council house. The Americans failed in their attempts to storm the council house but looted the town, burned cabins, and destroyed the corn crop before withdrawing back south of the Ohio and selling off the loot. Blackfish’s ragged wound became infected, leading some weeks later to his death from gangrene poisoning. Many Shawnees, seeing the likelihood of ever-increasing white incursions, left Ohio and moved farther west, away from the American settlements. In the spring of 1779, even before Bowman’s attack, some four hundred Shawnee warriors moved with their families to Spanish-controlled Missouri, at the invitation of the Spanish authorities.79

For all these reasons, by the time the Boone party arrived in Boonesborough in October 1779, there was at last the prospect of being able to plant and to harvest crops in the following year, though the winter of 1779–80 promised to be short of food. There had been no massive Indian attacks on the Kentucky forts since the siege of Boonesborough in September 1778. This is not to suggest, however, that the Kentucky to which Boone and his family returned was peaceful. There were still small-scale Indian raids in Kentucky—witness the killing of Colonel Callaway in March 1780. Most of the Shawnees who remained in Ohio were militant opponents of American settlements in Kentucky. Rebecca had good reason to be concerned about the risks of living near Boonesborough. Between 1775 and 1779 forty-seven people were killed defending or while hunting from Boonesborough.80

Boonesborough by late 1779 may have been less prone to large-scale Indian attack, but it remained small, filthy, ill fed, and dangerously unhealthy. Col. William Fleming described it: “Boones burg has 30 houses in it, stands in a bottom that is surrounded by hills on every side that commands it,… from which hills, small Army can do execution in the Fort which is a dirty place in winter like every other Station, there is a lick close to the post… in which there is a spring which serves the people in common that smells and tastes strong of sulphur there is likewise a Salt Spring or two but water weak in it.”81 The squalor and confinement in Boonesborough and the other Kentucky stockaded stations were sickening. There was little besides meat to eat. In January 1780 John Floyd wrote to William Preston: “If anybody comes by water I wish we could get a little flour brought down if it was dear as gold dust. Since I wrote, corn has been sold at the Fall for $165 a bushel.” In June of that year Floyd wrote to Preston: “People this year seem generally to have lost their health: but perhaps it is owing to the disagreeable way in which we are obliged to live, crowded in forts, where the air seems to have lost all its purity and sweetness. Our poor little boy has been exceedingly ill, & is reduced to a mere skeleton by a kind of flux which is common here, and of which numbers die. His mother is almost disconsolate, and I myself am much afraid we shall lose the child, and if we do I shall impute it to nothing but living in dirt and filth.”82

The settlers’ dependence on meat, and meat alone, had also harmed the settlers. Colonel Fleming, who had studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, described how sick the settlers were in 1779 at the Falls of the Ohio: “Several people died whilst we were here the disorder they complained of was occasioned by a relaxation of the solids, from bilious Complaints which brings on such Corruption of the fluids with a Visidness of the Juices that it degenerates and breaks out in cancerous eating soars I have seen the Maxillary and the glands about the throat and tongue in Old and Young persons entirely destroyed some have Vomited corrupted bile as green as Verdigrease so that the whole of the disorders that at this time reign here is occasioned by bile.”83 Fleming himself soon suffered at Harrodsburg from ailments like those he had seen at the Falls of the Ohio. His journal entry for March 1780 describes his condition:

Much indisposed. Got bled 12 Oz.… [T]he blood was solid like liver and black as tarr the symptoms returning with violence my head paining me greatly through the temples, above my eyebrows along the Sutures of my head and the hind part my eyes seemed so full and tense in the sockets that I could not turn them, I was bled the 22nd being determined to let the Vein breath till I found an abatement of the Symptoms… this did not happen till three pints… was in the basin and I was giddy… the blood would leave the extremities my fingers would turn pale and have all the Appearance of a Corps a noise like the rustling of waters was constantly in my ears and my memory failed me the blood now taken was covered all over with a seemingly putrid gelly.… I was no longer at a loss to account for the different disorders I had observed for cancerous like ulcers in the throat and glands and for the different symptoms in the fevers I had lived for a constancy on poor dried Buffalo bull beef cured in the smaok… without any addition but a piece of Indian hoe cake which made my breakfast and the same for dinner—it was owing to this coarse food that I had such a thick vicid and black blood.84

Colonel Fleming may have come close to killing himself by exsanguination, but he had the sharpness of mind to attribute his symptoms to diet. For months he, like the settlers at Boonesborough, had been eating only buffalo meat, with occasional bits of cornmeal cake. The throat and jaw sores that he described on himself and that he had observed in the settlers at the Falls of the Ohio sound like classic symptoms of scurvy, or vitamin C deficiency—including swollen, purple, friable, often bleeding gums.85 When Fleming returned to the Falls of the Ohio in 1783, after the Indian threat had receded and the settlers had more varied food, he reported in his journal that the inhabitants near Louisville were much healthier than they had been in 1779 and were “not subjected to the Phagadencie [teeth-eating] Cancerous ulcers and malignant fever so general when I was there in 1779.”86

Boone and his family did not linger at Boonesborough after their return there in 1779—whether that was because of the unhealthiness of the place or the unpleasantness of being in the same small station with Col. Richard Callaway, who had accused Boone of treason. Boone stayed in Boonesborough only long enough to confirm land claims before the Virginia Land Commission for himself (fourteen hundred acres on Stoner’s Creek), his brother George, and his son Israel. In late December 1779 Boone and his family and some other settlers, many of them Boone relatives, moved to a site six miles northwest of Boonesborough, where he had built a cabin and put in a corn crop. The settlement, called Boone’s Station, was near what is now Athens, in Fayette County. It was a simple and rough station that first winter—just half-faced camps put up in the snow that greeted them on their arrival.87

The winter of 1779–80 was so rough it became known as the “Hard Winter.” Colonel Fleming said the weather was “as severely cold as ever I felt it in America,” and in his journal he described the cane almost all killed by the cold, the hogs frozen to death in their beds, the deer, turkeys, and buffalo frozen or starved to death.88 By the end of 1779 the Kentucky River was so solidly frozen it could bear the weight of horses. In December John Floyd wrote to William Preston, “The Day is so cold that… the Ink freezes every moment so that I cant make the letter.”89 In January 1780 the frost at Bryan’s Station had penetrated the ground more than fourteen inches—as the settlers discovered when they tried to dig graves to bury two young men who had died of illness and cold. The next month Fleming reported the ice on the Kentucky River was nearly two feet thick.90

Daniel Trabue, camping that winter near the Green River, west of Boonesborough, said: “The snow was fully knee Deep.… The Turkeys had got poore. They would set on the treers all Day and not fly Down.… We could kill as many of them as we wanted but they weare too poore to eat.” By the time the hard winter finally broke at the end of February, Trabue reported: “The turkeys was almost all dead. The buffeloes had got poore. People’s cattle mostly Dead. No corn or but very little in the cuntry. The people was in great Distress. Many in the wilderness frostbit. Some Dead.”91 One family not far from Harrodsburg had camped in a rise in the ground near running water. The water rose in a winter storm and surrounded the rise, and a hard rain put out the family’s campfire. The man, seeing fire at another camp across the stream, went into the cold water to seek fire from the neighboring camp to relight his family’s fire. He was never seen again. His wife and children “perished in the Night with the extremity of the Weather.”92

Boone’s group survived the bitterness of the Hard Winter on scrawny buffalo, bear, deer, and turkeys and on the small amount of corn Boone had brought from North Carolina. In March, when the snow melted, the group put up cabins and stockades to guard against Indian attack.93 Within a few years there were fifteen or twenty families in Boone’s Station, many of them Boone kin, including three of Boone’s brothers, his married daughters Jemima and Susannah, and cousins named Scholl. Boone himself, with his family, moved several years later a few miles to the southwest, to a cabin on another land claim of his on Marble Creek.94 He and Rebecca lived there with their five children who were not yet married, six motherless children of Rebecca’s uncle James Bryan, and the Boones’ daughter Susannah and her husband, Will Hays, and their children. As if the cabin were not sufficiently filled with Boones, Rebecca became noticeably pregnant during the summer of 1780. It was her tenth pregnancy. Their last child, Nathan, was born on March 3, 1781, when Boone was forty-six and Rebecca was forty-two.95

At Boone’s Station Boone hunted, as he did throughout his life. He had also become a substantial citizen. He headed a large family and a large group of families. His settlement not only bore his name but was led by him. On lands his family owned, worked in part by their slaves, the Boones were growing corn and tobacco and raising cattle and horses. As the need to fight Indians receded, Boone turned more and more of his attention to the core passion of most settlers in Kentucky: accumulating real estate and trying to become rich in the process. Boone was not yet a licensed surveyor, but he had walked or ridden over much of Kentucky. Using his knowledge of the country, starting in 1779 he began to locate claims for others, typically holders of Virginia land warrants good for a specified number of acres in Kentucky. In 1781, for example, he entered into a contract with Geddes Winston, a Virginian holding warrants for five thousand acres in Kentucky, “to Locate the Said Warrants, for which Consideration the said Geddes Winston doth agree to give to Said Boon Two thousand acres of the aforesaid Lands.”96 It is likely that Boone also acted as a jobber, or middleman, for others—in each case finding a tract he believed to be unclaimed, estimating its size, buying a warrant for the appropriate number of acres with funds from a prospective purchaser of the tract (or using a warrant already owned by the prospective purchaser), entering a description of the tract with the county surveyor to be surveyed, and then selling the tract.

Apart from his activities as a locator and jobber, because Boone often went to Virginia’s land office in Williamsburg (moved to Richmond by the end of 1780), a number of Kentucky land buyers also entrusted Boone certificates showing their entitlement to a specified amount of land at a specified location, together with the funds needed to file their settlement and preemption claims.

In February 1780 Boone and several others set off for Williamsburg, carrying in their saddlebags more than $20,000 in Virginia currency, together with a number of land certificates. They spent the night at an inn in a small town not far from Williamsburg, locked the door to their room, and woke up the next morning to find the door open and the saddlebags and the money and certificates gone. The saddlebags were found empty at the foot of the stairs to their room, and a small fraction of the money was found stuffed in bottles in the cellar of the inn. Boone believed he had been drugged, “that the landlord was the chief plotter of the scheme, and that an old white woman was the instrument, and that she must have hidden in the room, either under the bed or elsewhere,” to unfasten the locked door. Some of those who had given funds and certificates to Boone did not hold him responsible. Others demanded repayment of their money. It took Boone years to repay these sums. “It was a heavy loss to him,” his son Nathan said.97

In 1778 Boone had been accused of seeking to betray Boonesborough to the British. Now some suspected he had made off with money others had entrusted to him. Nathaniel Hart, Boone’s friend and neighbor for years at Boonesborough, who did not look to him to repay the large sum he had given Boone for the purchase of warrants, wrote to his brother, who was similarly situated: “I feel for the poor people who perhaps are to loose even their preemptions by it, but I must Say I feel more for poor Boone whose Character I am told Suffers by it. Much degenerated must the people of this Age be, when Amoungst them are to be found men to Censure and Blast the Character and Reputation of a person So Just and upright and in whose Breast is a Seat of Virtue too pure to admit of a thought So Base and dishonorable. I have known Boone in times of Old, when Poverty and distress had him fast by the hand, And in these Wretched Sircumstances I ever found him of a Noble and generous Soul despising every thing mean.”98

Other settlers in Kentucky must have agreed with Hart’s assessment of Boone and his character. In November 1780, when Virginia divided its westernmost county Kentucky into three counties (Jefferson to the west around Louisville; Fayette in the center, including most of the bluegrass country; and Lincoln to the south of Fayette), Boone was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the militia of Fayette County. Soon afterward he was elected to be the county’s representative in the Virginia Assembly. In 1781 he was made the county’s sheriff.99

Boone had saved the lives of the salt-boilers from Boonesborough, painful as captivity was for many of them. He had been a leader in the defense of Boonesborough against attackers who outnumbered the defenders seven to one. Kentucky was being transformed by a flood of immigration that resulted in substantial part from that successful defense and from immigrant groups led by Boone or encouraged by his example. Boone had risen in rank and political position as well as in land that he owned or claimed. His fighting with the Indians, however, was far from over, and his land troubles were just beginning.