BOONE DID NOT GO TO HUNT IN KENTUCKY TO FULFILL A LIFELONG objective of opening up new territory for white settlement. Although his hunting and trail blazing doubtless played a key role in opening up Kentucky to white settlement, it would be after-the-fact and ideological history to think that he went into Kentucky for that purpose. Boone wanted to go to Kentucky because he had heard from John Findley and others that the land was rich and the wild game plentiful. He enjoyed hunting, he made his living hunting, and like most American settlers, he was interested in getting good land cheap.

Game abounded in Kentucky. Boone may have heard about the amount of game killed by Dr. Thomas Walker and his group, who in 1750 were the first British colonists to go up through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky from the south. A few earlier colonists had been taken across the gap as captives of the Shawnees or the Cherokees before Walker’s trip, but they did not write about what they saw.1 Walker did. Walker was a physician, merchant, surveyor, and landowner in Albemarle County, Virginia. In 1748 he had explored the Holston River in northeastern Tennessee with Col. James Patton, the first British settler to apply to Virginia for grants of trans-Appalachian land—the Patton who was to be killed by the Indians at Draper’s Meadow seven years later. In 1749 Walker was engaged by the Loyal Company, to which the Virginia Council had awarded 800,000 acres west of the Appalachians, to “go to the Westward to discover a proper place for a Settlement.”2 The company set off on March 6, 1750, from Dr. Walker’s home in Virginia, went west and south on the Holston River into northern North Carolina, crossed the Clinch and the Powell rivers, and then turned north up through a majestic gap that Dr. Walker called the “Cumberland Gap,” in honor of theduke of Cumberland, who had defeated Bonnie Prince Charlie and the rebellious Scots at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Walker and his men continued into the center of what is now eastern Kentucky. Instead of following an Indian trail northward, which would have led to the rich bluegrass country, Walker followed the Cumberland River toward the west and was discouraged by the thickness of the canebrake and the laurel thickets and by the lack of fodder for the horses. His party turned back, returning to Walker’s home in Virginia on July 13. Walker noted in his journal for that day: “We killed in the Journey 13 Buffaloes, 6 Elks, 53 Bears, 20 Deer, 4 Wild Geese, about 150 Turkeys, besides small Game. We might have killed three times as much meat, if we had wanted it.”3 A bag of that size in four months—for men whose objective was to explore, not to hunt—would have sounded temptingly plentiful to a hunter like Boone.

Boone did not go to Kentucky directly after he rejoined Rebecca in 1762. He moved with her and his children back to the Yadkin, to a farm on Sugartree Creek that probably was part of the land owned by Rebecca’s father. With the end of the French and Indian War in 1763 and the Indian attacks in 1763–64, settlers who had fled east came back to the Yadkin, and new settlers arrived. By 1765 there were four times as many people on the forks of the Yadkin as there had been when the Boones moved there in 1750.4 As a result, it was harder for Boone to find much game around his place, and he ranged farther, frequently hunting in the Great Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina. On some of Boone’s hunts up into the mountains, he took with him his young son James, his first child, who had been born in 1757, to teach him the business of hunting. Boone remembered hunting with James on snowy winter nights and “hugging him up to him” to try to keep him warm.5

Boone’s debts mounted as he bought hunting provisions and as the game dwindled. A lawyer remembered him as having had “more suits entered against him for debt than any other man of his day, chiefly small debts of five pounds and under, contracted for powder and shot.”6 In 1764 the Rowan County Court entered a judgment against Boone for the considerable amount of fifty pounds on account of the claims of one of his creditors.7 In the same year Boone and Rebecca sold their property on Bear Creek feeding into the Yadkin. Rebecca made her mark with an X on the bill of sale.8 The Bryans were richer than the Boones, but Rebecca Bryan Boone was substantially less literate than Daniel Boone.

If the flood of settlers that followed the end of the French and IndianWar made hunting harder for Boone, the peace also brought a new opportunity in Florida that Boone was quick to explore. In the war the British had ultimately defeated the French in North America—Canada was taken, and the French had abandoned Fort Duquesne. In the Treaty of Paris in 1763 the French acknowledged that the British had won North America east of the Mississippi, other than New Orleans. In addition, Spain also ceded the Floridas to Britain, getting back Havana in exchange, and France ceded Louisiana west of the Mississippi to Spain. In all, in the words of Francis Parkman, “half a continent… changed hands at the scratch of a pen.”9 Britain divided the Floridas into two new provinces: East Florida, consisting of most of what is now the state of Florida except the western panhandle, governed from St. Augustine; and West Florida, consisting of most of Florida’s western panhandle, the southern half of what is now Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana east of the Mississippi River, governed from Pensacola. West Florida’s governor, anxious to make the new province a British settlement, issued a proclamation offering one hundred acres for free to any Protestant who would settle the land.10

This must have sounded like an attractive land opportunity to Boone, particularly because the British government had recently limited westward expansion by its Proclamation of October 1763, which barred warrants of survey or the issuance of land patents beyond the Appalachians. The ban was intended to give the British government a rest from the high cost of fighting Indians, which had contributed to a huge jump in Britain’s national debt during the Seven Years’ War.11 That cost continued to mount after the Treaty of Paris well into 1764, as the Ohio Valley Indians and the Indians around Detroit, dismayed by France’s cession of eastern America to Britain and inspired by the Ottawa leader Pontiac, attacked Detroit, Fort Pitt, and other British forts as well as settlements in western Pennsylvania and Virginia, until British troops advanced into the Ohio Valley and both sides reached an exhausted peace based in part on recognition of the Ohio River as a boundary beyond which British settlement would not extend.12 The ban on settlement in the Proclamation of 1763 paralleled Pennsylvania’s 1758 renunciation, in the Treaty of Easton, of its claims on lands west of the mountains, a move made to induce the Indians to stop backing the French.

The West Florida proclamation must have seemed to Boone a tempting exception to the ban on western settlement. Boone and his younger brother Squire—named for their father, who died in January 1765—heard about theproclamation from friends from Virginia who stopped by Boone’s farm that fall on their way to look at the free land being offered in Florida. The price sounded right, and the land was little settled, which offered hope both of game and of appreciating land value. Another draw to trans-Allegheny backwoodsmen like Boone, having had no ready access to coastal markets, must have been Pensacola’s location on the Gulf Coast.13 Boone and his brother Squire, along with Boone’s brother-in-law John Stewart, joined their Virginian friends on their trip to Florida in the autumn of 1765.14 It was a trip of many hundreds of miles, but Boone promised Rebecca that he would return in time for her dinner on Christmas Day.

The Boones and their friends set off to backcountry South Carolina, then to Savannah and St. Augustine, and west across Florida to Pensacola. Not much is known about the trip. Boone’s son Nathan said that the party paid most of their expenses in the settlements from deerskins and from the gambling winnings of a Virginian in their party named Slaughter, who “was fond of gambling and won money going and coming back from Florida.”15 One wonders whether Slaughter was an honest gambler. Boone himself was less lucky. In the earliest surviving manuscript in Boone’s hand, an accounting of expenses that exemplified Boone’s lifelong phonetic approach to spelling, he recorded a debit of three pounds “to one watsh plade away at dise.”16

While the taverns and the gambling along the way may have been diverting, Boone and his traveling companions were unimpressed by what they found in Florida. The land was sandy and barren, the flies intense, and the only game they saw was deer and a few birds. The swamps were dismaying. Boone and the others came close to starving before they stumbled on a group of Seminole Indians who fed them venison and honey after Squire Boone gave a small shaving mirror to a young Seminole girl.17

Despite the disheartening conditions he found in Florida, Boone, according to Nathan, purchased a house lot in Pensacola and wanted to move there.18 Why? Pensacola at that time cannot have been a prepossessing place. The settlement was small, the fort dilapidated. Not long after Boone was in Pensacola, an English captain described to the British commander-in-chief in America the “poor Huts” in the fort and the poor condition of the men in them: “Their Barracks are covered with Bark on the Sides and Roof, which naturely Shrivels in a short time in the heat of the Sun.… The Firmament appeared thro’ the Top and on all sides, The Men walking About like Ghosts on a damp Sandy Floor, that is near a Foot under the Level.” Nothing keptout the vicious mosquitoes.19 But for all its flaws Pensacola had much to offer to Boone. Being on the Gulf Coast, it was accessible to European markets for exporting pelts and importing supplies. The Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws traded there. The backcountry was open for hunting and settlement. Florida was far from Boone’s creditors in North Carolina. Moreover, Boone never stayed in one place for very long.

Boone made it back to the Yadkin by Christmas 1765. He deliberately delayed a bit at the end so he could walk into his cabin at noon on Christmas and take his place at the dinner table on that day, as he had promised Rebecca.20 Boone told Rebecca that he had bought a lot in Pensacola and wanted to move there. She had already moved many times in the nine years since they were married, and her family and friends were in North Carolina and Virginia. Rebecca declined the proposed new move to a place more than seven hundred miles away, and Boone abandoned the lot in Florida and went back to hunting in North Carolina.21 Although Boone did not move to Florida, he did move his family three times in the next two years, each time farther up the Yadkin, farther away from the settlements and from creditors and closer to where Boone liked to hunt, high in the Blue Ridge. Moving upriver with him were members of his family and of Rebecca’s family, including Boone’s brother Ned (who had married Rebecca’s sister Martha), Boone’s brother Squire, and Boone’s youngest sister, Hannah, and her husband, John Stewart.22

Boone evidently kept thinking about Kentucky and the rich hunting that was said to be there. In the fall of 1767 Boone and William Hill, who had been with him on the trip to Florida, went west in search of Kentucky, crossing the mountains with the intention of reaching the Ohio River. They reached the headwaters of the Big Sandy River in what is now the easternmost part of Kentucky and continued northward toward the Ohio River about a hundred miles but then, according to Nathan Boone, “ware Ketched in a Snow Storm and had to Remain the Winter.” The country was hilly, scrubby, and uninviting, so the two went back to the Yadkin in the spring, not greatly impressed by what they had seen of Kentucky. It was not all bad, however. Boone and Hill had come across a lick near the present town of Prestonburg and had seen buffalo and other game lured to the lick by its saltiness. Boone was able to kill his first buffalo and to dine on its tasty hump.23

Late in 1768 John Findley, who had told Boone about the wonders of Kentucky when both of them were with Braddock’s army in 1755, showedup unexpectedly on Boone’s doorstep on the upper Yadkin. Perhaps Findley had been looking for Boone, who was already becoming known as a talented backwoodsman; perhaps Findley, by now an itinerant peddler working the backcountry, simply chanced on Boone as he traded from cabin to cabin. In any event Findley and Boone once again fell to talking about Kentucky, and Findley again described the richness of the game and the endless skins that had been brought to the trading station he had run at the Shawnee settlement Eskippakithiki not far from the Kentucky River, which ran north into the Ohio River. The settlement with the long Shawnee name may have given Kentucky its name, indirectly: the Iroquois called the town “Kanta-ke,” an Iroquois word for “fields” or “meadowland,” because the settlement was surrounded by hundreds of acres of cornfields.24 But no one is quite sure where the word Kentucky comes from. Boone’s biographers Filson and Draper thought it was a Shawnee word meaning something like “dark and bloody ground.” Col. John Johnston, a longtime Indian agent among the Shawnees, thought it was Shawnee for “at the head of a river.”25

As an Indian trader before the French and Indian War, Findley had traveled to Eskippakithiki by water, coming down the Ohio River and up the Kentucky River, and had never gone by land between North Carolina and Kentucky. Nevertheless, when Boone described the difficulties he and Hill had encountered crossing the mountains and heading north into the headwaters of the Big Sandy, Findley said that there had to be a better way across the mountains, probably to the west of where Boone and Hill had been, because the Cherokees regularly came north to make war against the northern Indians.26 While Findley could not show Boone where the trail crossed the mountains south of Kentucky, not having been there, once they were in central Kentucky, he would be able to show Boone where to find salt licks, grazing grounds, and the Red and Kentucky rivers leading up to the Ohio.

The time was right for Boone to try again to find Kentucky’s hunting grounds. Game was getting scarcer on the Yadkin, and Boone’s creditors were pressing him. It was also more likely that Boone would be able to lay claim to land in Kentucky. It was true that the Proclamation of 1763 barred surveying and settling land west of the Appalachians, but the colonists were hopeful that the Proclamation was a temporary moratorium, not a permanent bar, and the British, their finances strained by the cost of the war with France, had done little to police the ban on trans-mountain settlement. Moreover, in November 1768, under the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquoisceded to the British their claims to lands between the Ohio River and the Tennessee River. Few Iroquois lived in these lands, but the Iroquois claimed them by right of conquest and signed the treaty not only as the confederate nations of the Iroquois but also on behalf of their “Dependent Tribes,” the Shawnees, Delawares, and Mingos of Ohio.27 Among Indian tribes that left only the Cherokees, living to the south of Kentucky, with some claims to much of Kentucky.

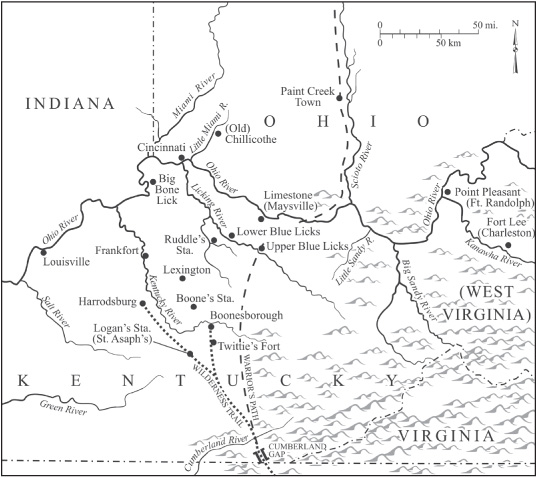

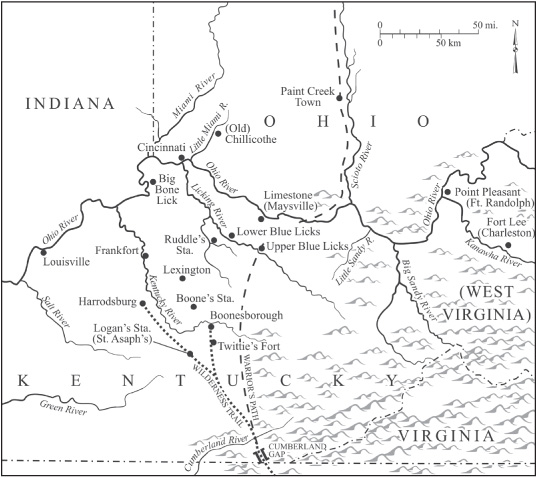

Boone’s Kentucky and Its Neighbors

Map by Mary Lee Eggart

The Shawnees had been largely driven out of the area by the Iroquois. The Shawnees no doubt still viewed Kentucky as theirs, and there were still many Shawnees, perhaps three thousand of them, despite the devastating effect of European diseases and of wars with the Iroquois and the Cherokees. Although the Iroquois claimed the land was theirs to cede by right of their earlier defeat of the Shawnees, the Shawnees, as the British general Thomas Gage recognized, “were exasperated to a great Degree” because the Iroquois“have Sold the Lands as Lords of the Soil, kept all the Presents and Money arising from the Sale, to their own use, and… the White People are expected in Consequence of it, to Settle on their [the Shawnees’] hunting Grounds.”28 After the British recaptured Fort Duquesne in 1758, many Shawnees moved their villages north of the Ohio River in what is now Ohio, but some still maintained at least winter hunting camps south of the river in Kentucky.29 The Shawnees, after the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, became the spearhead of Indian resistance to white expansion into the Ohio Valley.30

The 1763 proclamation and the Shawnees were thus both substantial problems for whites who wanted to settle in Kentucky. Land speculators, however, tend to be optimistic about possible opportunities. Kentucky in 1768 must have looked to Boone to be comparatively devoid of claimants. Squatters might be able to get a leg up on claiming land in the Kentucky part of Virginia under that colony’s law permitting a Virginian to settle up to five hundred acres of uninhabited land for himself.31 As the British Board of Trade reported to the Privy Council in 1771, the colonies had always given preference to actual settlement and improvement, whether legal or not, when it came to granting land titles.32

Boone and Findley decided to look for the warrior’s trail across the Cumberland Mountains and up into Kentucky.33 They waited until early May 1769, after Boone and the other Yadkin men who went with them had finished the spring planting on their farms. The group consisted of Boone, Findley, Boone’s brother Squire, Boone’s brother-in-law John Stewart, and three neighbors from the Upper Yadkin—Joseph Holder, James Mooney, and William Cooley—who were to act as camp keepers, preparing and packing the skins. Among them they probably had some ten or fifteen horses to carry their gear—shot, powder, flints, kettles, traps, blankets, and the like—as well as the packed skins.34

Fighting miserable weather, the party headed west in northern North Carolina, crossing the Holston, Clinch, and Powell rivers, and came to the Cumberland Gap, which led at an elevation of some sixteen hundred feet through towering cliffs. Boone, seeing signs that many had traveled on the path through the pass, realized he was on the Warrior’s Path. Going north through the gap, Boone and his group left North Carolina and entered what is now Kentucky. They crossed the Cumberland and Rockcastle rivers. Boone climbed the ridge to the north of the Rockcastle Valley and looked northward into the Kentucky River watershed. His party went on toward thenortheast, to a creek that flows into the Kentucky River at what is now Irvine, set up a station camp (the creek to this day is called Station Camp Creek), and began going off in small groups to hunt and to bring the kill back to camp.

Findley went farther north to see if he could find what was left of Eskippakithiki, where his trading station had been. That was not hard because the Warrior’s Path went close by their station camp and led past Eskippakithiki before continuing on northward to the Ohio River. Findley found the town burned, but the remnants of the stockade and gateposts were still recognizable. Findley showed them to Boone and Stewart. This evidence backed up what Findley had been telling Boone about Kentucky. It was also heartening that Findley now was where he had been before and so could orient Boone. While the rest of the men hunted, prepared skins, and kept camp, Boone and Findley explored farther north along the Kentucky River and the Elkhorn.

The country was already rich in bluegrass, even though that grass was probably not native to America but may have come into the region when Findley and other traders brought in trade goods packed in English hay.35 Boone and some of his companions climbed a hill to look at the rich country to the north, and they liked what they saw. In his early biography John Filson has Boone say, “On the seventh day of June, we… from the top of an eminence, saw with pleasure the beautiful level of Kentucke.”36 Kentuckians to this day celebrate June 7, the date of this viewing, as Boone Day.

For six months Boone’s group, as Boone put it, “practiced hunting with great success.”37 They prepared and packed hundreds of dollars’ worth of deerskins. Boone may also have been scouting out the most desirable lands for possible future settlement, either for himself or for Col. Richard Henderson, the ambitious and grandiloquent North Carolinian who was later to organize a company to lay claim to almost all of Kentucky. It looked as if Boone and his companions would make good money on the long hunt into Kentucky, but that prospect was destroyed on December 22, 1769. On that day, as Boone put it in Filson’s account: “John Stewart and I had a pleasing ramble, but fortune changed the scene in the close of it.… In the decline of the day, near Kentucke river, as we ascended the brow of a small hill, a number of Indians rushed out of a thick cane-brake, and made us prisoners. The time of our sorrow was now arrived.”38

The Indians were Shawnees, led by a war chief known to the whites as Will Emery, or Captain Will. Having been on a fall hunt, the Shawnees were on their way back to their homes north of the Ohio River. They had recentlytaken some two thousand skins from a hunters’ base camp on the Green River farther south and west in Kentucky. With raised tomahawks the Shawnees demanded to be taken to Boone’s main camp. Boone led them first to small caches, making as much noise as possible in an attempt to alert his fellow hunters so they could hide most of their pelts. Unfortunately, when Boone finally led the Indians to the main camp, all of the skins were still there, and the other members of Boone’s party were nowhere to be seen. The Indians took Boone and Stewart’s long rifles and loaded the pelts—the fruits of some eight months of hunting—onto the white hunters’ horses, which the Indians also took.39

Captain Will treated Boone and his companions with remarkable restraint, if we bear in mind that Boone’s party was poaching on Indian land. “In the most friendly manner,” as Boone later recalled it, the Shawnees provided Boone and Stewart with two pairs of moccasins apiece, a trade gun, and some powder and lead so that they could kill enough meat to survive on the journey back east across the mountains.40 Captain Will also gave Boone and Stewart some firm parting advice: “Now, brothers, go home and stay there. Don’t come here any more, for this is the Indians’ hunting ground, and all the animals, skins, and furs are ours; and if you are so foolish as to venture here again, you may be sure the wasps and yellow jackets will sting you severely.”41

After the Indians left, Findley and the three campkeepers returned to the station camp and decided, in light of the Indians’ seizure of their goods and strong warning, to go back to the settlements. Boone asked them to stay a couple of days, to see if he and Stewart could retrieve some of the horses the Indians had taken. Boone and Stewart went after the Indians, overtook them in two days, and were able in the dark of night to make off with four or five horses and head back south toward their camp. The morning of the second day, however, Captain Will and a dozen mounted Shawnees caught up with Boone and Stewart and took them captive again. The Indians laughed with pleasure at their recapture of the horses and the two white men. They took a bell from a horse, tied it around Boone’s neck, and made him prance around jingling it. “Steal horse, ha?” they said in English. Then they once again headed north toward the Ohio and their towns, taking Boone and Stewart with them. On the evening of the seventh day, only a day’s journey from the big river, Boone and Stewart each grabbed a gun and ran into the thick cane while the Indians were making camp. The Indians could not findthem before nightfall, did not go after them in the dark, and set off north for the Ohio in the morning.

Boone and Stewart, finding their station camp abandoned, headed south, meeting up with Findley and the campkeepers on the Rockcastle River. Boone and Stewart were pleased to find that the party had been joined by Squire Boone and another hunter, Alexander Neeley, who had come out from North Carolina with new supplies, traps, and ammunition.42 Despite the Shawnees’ warning about the stinging of the wasps and the yellowjackets, the two Boones, Stewart, and Neeley went northwest to continue their hunting. The campkeepers went back to North Carolina and never came back to Indian country. Findley went back to Pennsylvania, resumed trading, was robbed again by Indians, went west again in 1772, and disappeared without a trace.43

Boone, Stewart, Neeley, and Squire Boone were alone in Indian country. But the winter hunting was good. This time they had made their base camp at a place well away from the Warrior’s Path, which had led Captain Will and his braves close to them before. The location of the new base camp, on the north bank of the Kentucky River not far from the mouth of the Red River, was rich in beaver and otter.44 There was even an element of frontier literary culture in their hunting. The hunters went off by themselves or in twos—generally Boone with Stewart, Squire with Neeley—and came back to their base camp. Boone had a copy of Gulliver’s Travels, which he read aloud to the others. One day, after Boone had been reading about Brobdingnab, the land of giants, and its capital, called Lorbrulgrud, or Pride of the Universe, Neeley came in and announced that “he had been that Day to Lulbegrud and had killed two Brobdernags in their Capital.” Only with some effort were his companions able to figure out that Neeley had been hunting at a salt lick by a creek and had killed two buffalo. The men called the creek “Lulbegrud”—the name the creek still bears—which may have been as close as Neeley could come to pronouncing “Lorbrulgrud.”45

Early in 1770 Stewart went to the south side of the Kentucky River to trap and hunt, while Boone worked the north side. They agreed to meet back at the base camp in a specified number of days, but Stewart did not show up. Boone crossed the river, found what was left of a recent fire, and saw Stewart’s initials on the bark of a tree—but no Stewart. Had Stewart quit and run back to the settlements? Or had he decided to run away from his wife, Boone’s youngest sister, Hannah? Boone thought it unlikely. Stewart hadfour children and was devoted to his wife. Boone once said “he never had a brother he thought more of than he did of John Stewart.”46 Five years later, when Boone and a team of axemen were blazing the Wilderness Road up through the Cumberland Gap to the Kentucky River, close to where Boonesborough was built, the axemen found human bones in a hollow tree, together with a powder horn that Boone would have recognized as Stewart’s even if Stewart had not carved his name on it. Boone thought he could recognize Stewart’s features from the skull. One of the arms had been broken, and discoloration from a lead ball was still visible on the bone. They saw no other sign of injury and did not find Stewart’s rifle. Boone guessed that Stewart had been shot by Indians and had dropped his rifle as he sought to escape, perhaps because of his wounded arm.47 Unable to hunt, he may have crawled into the hollow tree for some protection from the winter cold and froze or bled to death there.

Stewart’s disappearance in 1770 was too much for Neeley, who went back to the settlements by himself. The next year Neeley, who had been hunting with another group of long hunters, became separated from his party and lost his gun. Half-crazed and starving, his only food was a stray Indian dog that he had managed to stab to death. Neeley was still carrying what was left of that dog, “alive with maggots,” on his back when Boone and Squire, who were on the way back to North Carolina at the end of their long hunt, happened to find him in the woods. They fed Neeley and helped him back to the settlements. Later he moved with his family close to the Cumberland Gap and was killed by Indians near his house in the mid-1790s.48

Boone’s group in Kentucky was getting smaller and smaller. In May 1770 Squire Boone left for North Carolina, carrying a full load of winter pelts to sell in the settlements. Until Squire’s return with supplies in July 1770, Boone was completely by himself. So far as he knew, he was the only white man in Kentucky. Was he miserable? Evidently not. Boone could have gone back to the settlements with Squire but chose to stay in Kentucky, alone and with limited ammunition. He hunted and explored and moved his camp frequently, often sleeping in the canebrakes “to avoid the savages.” In Filson’s account Boone says: “I was happy in the midst of dangers and inconveniences. No populous city, with all the varieties of commerce and stately structures, could afford so much pleasure to my mind, as the beauties of nature I found here.”49 The florid language and the echoes of Rousseau certainly came from Filson, but there was other evidence that Boone loved being byhimself in the woods. Sometime around 1770 a group of long hunters led by Caspar Mansker heard a strange sound in the wilderness of Kentucky. Mansker had his companions take cover, while he crept forward toward the noise. He found Daniel Boone, alone in the middle of a clearing, lying flat on his back on a deerskin and “singing at the top of his voice.”50

Boone spent much of this time alone exploring the country. Filson’s Boone was to say that “the diversity and beauties of nature I met with in this charming season, expelled every gloomy and vexatious thought.”51 Boone may well have been susceptible to the beauty of Kentucky. As a hunter, he must have loved the abundance of game. He may even have been taken by the beauty of living things that were not edible. Filson records among the birds of Kentucky, for example, “the ivory-bill woodcock, of a whitish colour with a white plume, [which] flies screaming exceeding sharp. It is asserted, that the bill of this bird is pure ivory, a circumstance very singular in the plumy tribe.”52 Boone may have told Filson about the ivory-billed woodpecker. The birds were in Kentucky in Boone’s day. A 1780 journal gave a vivid description of one shot not far from where Boonesborough was to be built, and a few decades later, John James Audubon, the celebrated painter of The Birds of America, painted his picture of two ivory-billed woodpeckers in Henderson, Kentucky, and wrote that people killed the ivory-billed woodpecker “because it is a beautiful bird, and its rich scalp attached to the upper mandible forms an ornament for the war-dress of most of our Indians, or for the shot-pouch of our squatters and hunters, by all of whom the bird is killed merely for that purpose.”53

Quite apart from aesthetic considerations, however, Boone through his solitary explorations was getting to know his way around Kentucky far better than any other white man. That knowledge was to prove valuable to him as a hunter and trapper, guide to settlers, scout, militia officer, surveyor, and land speculator—in all of the ways Boone, by leading settlers to Kentucky directly and by example, was to play a key part in the westward flood of settlement that transformed America. According to Boone’s son Nathan, after Squire left, Boone discovered in his explorations several of Kentucky’s principal salt licks by “following the well-beaten buffalo roads leading to them.” He visited the Upper and Lower Blue Licks on the Licking River and saw thousands of buffalo at the licks. He went north to the Ohio River and followed its southern bank to the Falls of the Ohio, a place of obvious future commercial importance, because the falls were the only impediment to navigation on theOhio’s long trip from Pittsburgh to the Mississippi. Unless and until a canal with locks was built on the site, freight would have to be handled and transshipped there. The south bank of the Falls was to become the site of the city of Louisville. Perhaps not surprisingly, Boone found near the lower end of the Falls of the Ohio, on the Kentucky side, the remnants of an old trading house.54

Boone turned back east, probably crossing the Kentucky River near what later became Frankfort. He tried to stay out of sight of Indians, but on the Kentucky River he came upon an Indian fishing, sitting on a fallen tree that was sticking out over the water. Boone later told his son Nathan, cryptically: “While I was looking at him he tumbled into the river and I saw no more of him.” Nathan told Boone’s biographer Draper, “It was understood from the way in which he spoke of it that he had shot and killed the Indian; yet he seemed not to care about alluding more particularly to it.”55 This is a strange story. Boone was not a random killer of Indians. If he was traveling by himself in Indian country, seeking to hide from the Indians, the noise of a shot could have given away his location. Other versions of the story, from other Boone relatives, suggest that Boone at the time had encountered Indian sign in other directions, and the fishing Indian had the bad fortune to be in the way of Boone’s most promising escape route.56

Was Boone ever lost during his explorations? That was an obvious question and one he may have been asked often as his reputation grew. When Boone was eighty-five years old and living in Missouri, the young artist Chester Harding asked him one day, after Boone had described one of his long hunts, if he had ever gotten lost, having no compass. “No,” he said, “I can’t say as ever I was lost, but I was bewildered once for three days.”57

After Squire rejoined Boone with new supplies in July 1770, the brothers went back to hunting. Not until March 1771 did they head back toward the settlements, their horses laden with pelts. They made it safely through the Cumberland Gap into Powell’s Valley, when a group of six or eight Indians—accounts vary about whether they were Cherokees or northern Indians—showed up at the Boones’ campfire. The Indians drank from Boone’s flask, talked of hunting, and then proposed to swap their trade guns for the Boones’ far better long rifles. When the Boones declined, the Indians, who outnumbered the Boones, took all of the Boones’ furs and several of their horses. Once again, the Boones had lost the fruits of months of hunting and trapping.58 Their only yield from a hunt of two long years was from the twoloads of pelts Squire had been able to bring out of Kentucky before this second robbery.

Boone did not get back home to the upper Yadkin until May 1771. A story, perhaps apocryphal, captures just how long his hunt had been. When he got back to Beaver Creek, Boone found his family at a frolic at a neighbor’s cabin. Boone’s hair and beard were long and disheveled, and no one recognized him as he stood at the edge of the dancing. He went up to Rebecca on the dance floor and silently extended his hand for a dance. She declined. “You need not refuse,” Boone cried, “for you have danced many a time with me.” Recognizing his voice, Rebecca burst into tears and threw her arms around his neck. The neighbors, too, realized the hairy stranger was Boone; “the dancers now took a rest, while Boone related the story of his hardships and adventures in the romantic land of Kentucky, where he had encountered bears, Indians, and wild cats—and had seen a country wonderful in its beauty to behold.”59

A dozen years later Boone told Filson—as recounted in Filson’s florid words—that after his long trip to Kentucky he “returned home to my family with a determination to bring them as soon as possible to live in Kentucke, which I esteemed a second paradise, at the risk of my life and fortune.”60 Boone acted on this determination and would risk his life and ultimately make and lose a fortune in Kentucky.