When he is standing as he is now, head tilted back before melting into a slow roll of the neck, pink tongue poking out from between his lips before retreating again, he is likely to send an instinct of unease starting through the mind of his opponent. Doubt will occur, a thought slow and painful, and then they will have lost already, before the bell is rung or the fight begun. When he is standing as he is now, feet planted squarely in his corner, body slack and casual, it is impossible to believe that Kazushi Sakuraba can be defeated, and it is for this certainty that they gather by the thousands to watch him.

Across him in the ring stands a young Brazilian fighter called Wanderlei Silva. As a fighting proposition, he is a perfectly conditioned map of spheres, half spheres and relentless straight vectors. Each muscle dovetails tightly one into the next, and with Silva, things once released – whether it is his devastating roundhouse kicks, his hard stomps or his slamming knees to the head – must roll towards their designated conclusion, no matter the cost or peril. If Sakuraba works laterally, spider frisking across his web, then Silva hurtles forward with the inevitability of the lance. And it is this determination that Sakuraba must harness and expose as Silva’s weakness – for Silva has no other weakness.

They have packed out the Tokyo Dome, fans of the fighting sport, to witness which will be stronger: laxity or tautness, laterality or verticality, Japan or Brazil, but there is not much doubt in their minds that their hero cannot be beaten. It is, after all, his game, and he has written the very terms of the game’s brutality through his apparent uninterest. And so these hundred thousand fans are not so very nervous; they do not believe that fate can let them or Sakuraba down. All across the stadium they are settling further into their seats, elbows propped on knees in a stance of comfortable anticipation. There is nothing they enjoy more than the privilege of watching their hero perform.

In their separate corners the two fighters are turning round, slow and cautious, senses adjusting to the heightened sensitivity that forms a constituent part of the fighting ring – the immaculate detailing of cold air on skin, the touch of glove and the hard hollow clapping of hands, feet bouncing slow on the mat. Their ears are keen to the subtle sounds all around, the solitary cheering of an impatient fan in the left side of the second tier, the meticulous layering and intersecting of the announcers’ voices, moving through the air in different languages and rhythms, pronouncing their names, their fight records, their strengths and their provenance. Then the bell rings, and the fight begins.

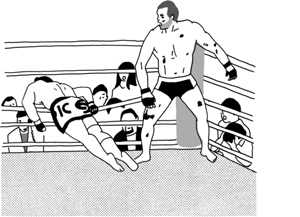

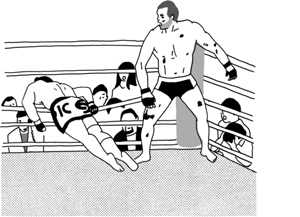

A roar leaps out with the ringing of the bell, but then the stadium falls silent as, within seconds, Kazushi Sakuraba, the man who can’t be beaten, the man who has never known the darkness of a knockout or the choke of a tight submission, falls to all fours. He remains there, head down and bleeding from the face as the Brazilian fighter punches and kicks, dances and lunges and taunts him. The silence extends for several long moments, a carefully pieced mosaic of a thousand individual silences, through which the hard slaps of flesh hitting flesh can be heard. Then suddenly that fragile silence erupts into the fragments of a screaming more frenzied than before, and the crowd is on its feet.

Down in the ring, body crouched low to the ground and trembling, eyes swelled shut, face blistering, the fallen fighter sighs. A soft sigh, slipping out from his mouth as a whisper and hanging heavy on the air before him. And as he crouches there, body absorbing a hailstorm of blows, he abruptly perceives the blessedness of the knockout, the sanctity of oblivion. Through his groans, now coming heavier, now coming faster, he smiles, just for a moment, because it is so strange – being stopped, and darkness so close. From across the ring, the referee sees that smile, and then he knows, as he watches, that Sakuraba is getting killed. He is not merely losing, he is not merely being beaten, he is being killed, slowly and systematically.

And so, swallowing hard, he steps in to end the fight. Doctors flock into the ring, and the referee looks on in wonder as they miraculously enact a dirty resurrection. He watches as Sakuraba comes back to life to address the crowd, limbs bleeding, face raw and swollen like the faces of the drowned. He listens as the suicidal request for a rematch is hailed by a blood-thirsty crowd that loves its hero even more in defeat and recklessness, knowing all the while that once Sakuraba exits the stadium stage he will collapse and remain in collapse, so many bridges of consciousness fallen.

Sakuraba disappears down the long gauntlet leading out of the stadium. The referee looks up at the crowd, screaming in fear and enthusiasm. Something has come undone in that bright spangled mass seething heavy beneath the lights; some sky has fallen. The announcer looks bewildered, the promoters stand helpless and hurrying, and there is no telling how long this confusion will last. Then, from inside the ring, the Brazilian fighter throws his head back and screams, ‘I love Japan!’

The promoters stare at him dumbfounded, and instinctively security men move forward. Ringside, a row of men in expensive pressed suits avert their gaze. They wait, nervous and uncertain, as the crowd hesitates. Then a trembling begins in the belly of the stadium, spreading slow to the walls and mounting in register. And so the triumphant fighter says it again, and then again, arms held up and head flung back so that his body is nearly bent double – ‘I love Japan! I love Japan!’ – and when he straightens again, fist shaking the winner’s trophy, muscles numb and head spun by vertigo, there is nothing touching him but the noise of the crowd’s roar.