CHAPTER 6

STATUS ANXIETY

The 2012 Champions League semifinal second legs were more dramatic than anyone could have expected. On the Tuesday night, Bayern Munich won a shoot-out against Real Madrid after Cristiano Ronaldo and Sergio Ramos both missed. The following night, Chelsea overcame Barcelona in an incredible match at Camp Nou, the most surprising element of which was Lionel Messi missing a second-half penalty. Had he scored, Barcelona would have been 3–1 ahead and, with Chelsea reduced to ten men after John Terry’s red card, surely on their way to the final.

In the space of twenty-four hours, the two best players in the world, possibly among the best that have ever played the game, each missed a penalty. I buy into the argument that over the years their personal rivalry has pushed them to improve—without Messi, I doubt Ronaldo would have reached the level he has, and vice versa—but following each other’s penalty misses? That was too weird.

We all know that these things can happen. Anyone can miss a penalty. And big players will miss big penalties, because they are usually the ones who take them. But this was the Champions League semifinal, the most important game of that season given that both clubs had made the competition their priority and, arguably, were just a penalty away from reaching the final. So why did they miss in this particular game?

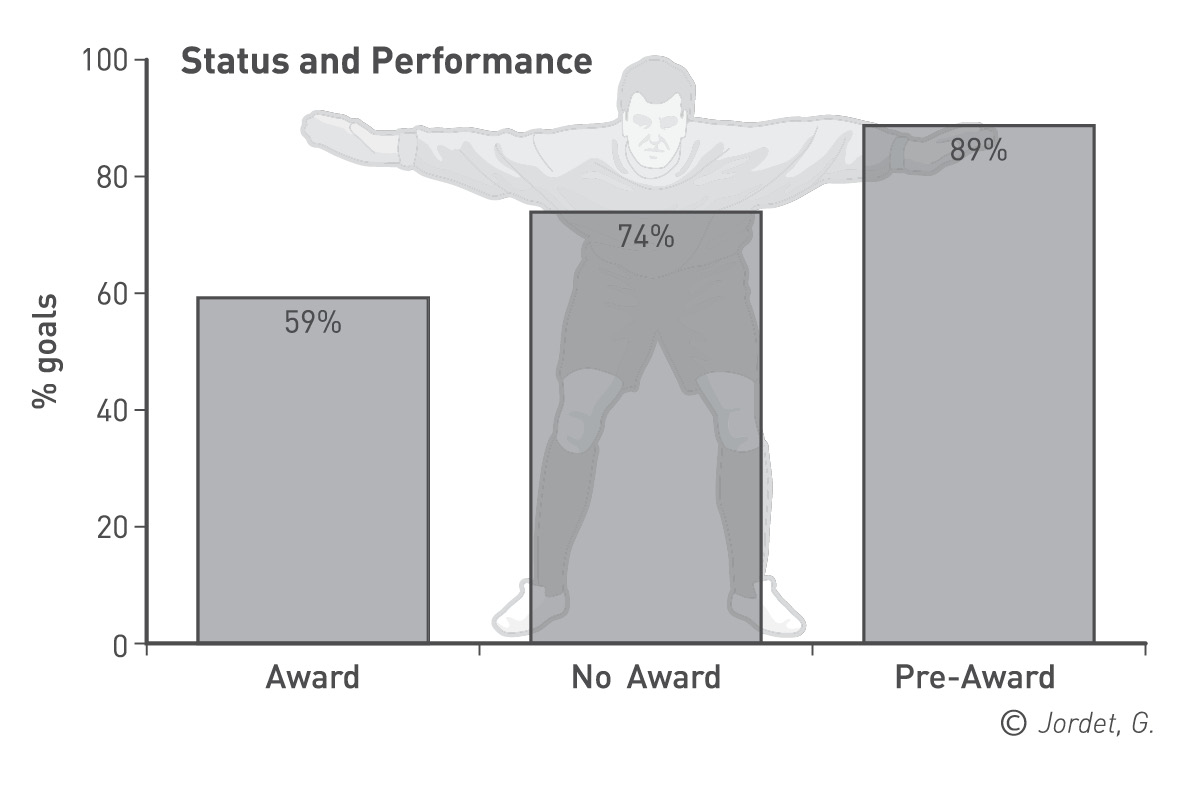

Geir Jordet thinks he has the answer. He looked at thirty-seven shoot-outs from World Cup, European Championship and Champions League games. There were 298 different players taking 366 kicks. He divided the players into three categories: current-status players, no-status players, and future-status players. By current-status he was referring to players who have won individual recognition for their performances, either a top-three place in FIFA’s World Player of the Year awards, the Ballon D’Or vote, South America’s Footballer of the Year, the World Cup Golden Boot, or a place in UEFA’s Team of the Year: 41 players, taking 67 penalties, fell into this category. No-status players were those who had not won and never did win awards; future-status were those who had not won awards when they took their penalties, but would go on to win awards in the future.

Figure 24: Status and performance

His results were surprising: overall, 74% of the penalties were scored, but the current-status players only scored with 59% of their kicks; the no-status players scored with 74% and the future-status players with 89%. The current-status players also missed the target more often than the others, on 13% of their kicks, compared to 7% for future-status players and 5% for no-status players.

Jordet named examples of players whose penalty records changed after winning awards. Frank Lampard scored for England against Portugal in 2004. In 2005, he came second in FIFA’s World Player of the Year award and the Ballon D’Or. In 2006, against Portugal again, he missed a penalty. Ronaldo, in that same game in 2006, scored the winning penalty for his country; by the time he stepped up for Manchester United in the 2008 Champions League final he was Ballon D’Or silver medalist (he would go on to win gold, among many other awards, that season) and had been named in UEFA’s Team of the Year. He missed his penalty against Chelsea.

OK, two players do not make an analysis stand up, but there are others who have missed important penalties. Messi, as we know. Steven Gerrard. David Beckham. Clarence Seedorf. Paolo Maldini. Diego Maradona. Jaap Stam. Didier Drogba. Roberto Baggio. Andriy Shevchenko. Marco van Basten. Raúl. Zico. Michel Platini. What is going on here?

“Current-status players have more to lose and therefore their fall will be bigger,” Jordet explained. He recommends that the coach identifies which players have the highest public status or most inflated public expectations, “because these individuals are likely to experience extra performance pressure” and might need to be taught coping mechanisms.*

Jordet also found that the current-status pattern occurs on a team level as well: teams with more superstars are more likely to perform badly in penalties. He noted that teams with 20–50% of current-status players scored 67% of their penalties compared to teams with no-status players at 86%, and 1–20% of current-status players at 71%.*

I wanted to look deeper into his results and see if the pressure of expectation for current-status players really is the common factor explaining why big players miss big penalties. There was only one place for me to start: when the best player in the world missed a penalty in the biggest game in the world.

*

The headline was short and sweet. It ran on April 7, 1991, in Gazzetta dello Sport: “Baggio, il gran rifiuto” (Baggio, the great refusal). It was a clear nod to the country’s most famous literary gran rifiuto, which is how the poet Dante referred to Pope Celestine V’s abdication of the Papacy in 1294 in his most celebrated work, the Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy). Celestine was the first Pope to formalize the resignation process, and Dante wrote of a nameless figure he saw in Hell: “Vidi e conobbi l’ombra di colui che per viltade fece il gran rifiuto” (I saw him and I knew his soul, he whose cowardice had made the great refusal).*

The day before the Gazzetta dello Sport pronouncement another deified figure had abdicated his responsibility.* Roberto Baggio, after five successful years at Fiorentina, had returned to Florence for the first time with his new club Juventus. He was nervous. He had scored all thirteen penalties for Juventus that season, but when his coach Luigi Maifredi asked him the night before the game if he wanted to take a penalty against Fiorentina, his eyes betrayed the answer.

Fiorentina fans had made no secret of their displeasure at the club selling their star player to hated rivals. Baggio, then twenty-three years old, knew his career was about to take a big leap forward, but he was suffering inside. As he reportedly told a friend a few days before the return to Florence, “It’s about time I decide what I want to do when I grow up.”

A few years earlier, Nicolà Berti had been so upset at the abuse he received from Fiorentina fans when he first returned to the club after joining Inter Milan that he was taken off after half an hour. Baggio lasted longer than that, despite the incessant taunts: “Baggio puttanà, l’hai fatto per la grana!” (Baggio, you whore, you did it for the money!)

When Stefano Salvatori brought down Baggio five minutes into the second half, referee Rosario Lo Bello had no hesitation in awarding a penalty. Baggio had already told his teammates before the game that he would not be taking a spot kick, so Luigi de Agostini, penalty taker the previous season, stepped up. As Baggio walked away from the goal, his teammates Julio César and Marco de Marchi embraced him, understanding what this moment meant. Fiorentina goalkeeper Gianmatteo Mareggini saved de Agostini’s effort. Diego Fuser went on to score the only goal of the game, and Fiorentina won 1–0.

Had de Agostini scored, had Juventus won the game, this story would be different. If, when Baggio was substituted ten minutes later, a female fan had not thrown a Fiorentina scarf at his feet, this story would be different. Maybe if Baggio, on seeing the scarf, had not picked it up and, clutching it, applauded his former fans, this story would be different. But he did.

Baggio had embraced his great friend at Fiorentina, Stefano Borgonovo (who tragically died in the summer of 2013), before he left the pitch. Borgonovo did a double-take when he saw Baggio bend down to grab the scarf: “He would never have picked up the scarf if he remembered he was playing for Juventus.”

Fiorentina president Mario Cecchi Gori led a standing ovation as Baggio walked off. That started the turnaround from whistles to cheers, as the crowd, briefly, fell back in love with its former hero. One set of fans unfurled a banner that read “The war is over, give us back the hostage.”

If anything, it was a moment of closure between the player and the club, a final gesture before Baggio could move on. Not that he had much sympathy from the press, or indeed his own teammates. De Agostini said he didn’t mind stepping in because “I’m a guy who takes responsibility.” Maifredi understood Baggio’s decision but “still hoped he would take the penalty.” Juventus president Gianni Agnelli wanted Baggio kept on the bench all game, brought on just for the penalty and then taken off again.

A poll of Gazzetta readers voted 81% that Baggio was wrong to avoid taking the penalty. Its journalist Alfio Caruso wondered if the decision hinted at a mental weakness: “Baggio started to behave like a luxury nonleaguer . . . It’s a paradox but this is the transfer that might damage his career the most as it has shown how vulnerable he is, how weak his character and how fragile his psychology.”

“Baggio was scared, silent, still, nonexistent, he had shrunk,” wrote Gazzetta’s Claudio Gregori. “Not taking the penalty was a proper desertion. He was a victim of that psychoanalytic group session where one takes his own past. He probably needed Freud more than Maifredi.”

Two years later, in 1993, the “deserter,” described by former Fiorentina teammate Giancarlo Antognoni as “just a man like anyone else,” was FIFA World Footballer of the Year and Ballon D’Or winner. By the time the 1994 World Cup came around he was the star of Italian soccer. He had two problems, though: one, he went into the tournament with two injuries, a knee that had bothered him all season and tendonitis in his right foot. The other was coach Arrigo Sacchi, whose adherence to a compact 4–4–2 system left little room for a fantasista such as Baggio.

Sacchi had tried out over seventy players in the build-up to the tournament—so many, in fact, that one magazine ran pictures of the Pope, Rambo and Popeye under the headline “Arrigo, have you forgotten anyone?”

Italy lost their opening match, against the Republic of Ireland, then beat Norway after Sacchi had controversially taken off Baggio on 20 minutes following goalkeeper Gianluca Pagliuca’s red card. “This is crazy,” lip-readers claimed Baggio said as he trudged off. So much for Sacchi’s promise that Baggio was as important to Italy as Maradona was to Argentina. “His creativity often felt trapped in Sacchi’s system,” said teammate Gigi Casiraghi, who’d expected to be withdrawn instead. “He had some problems with the coach.” Casiraghi proved a better option for the team a man down, and Italy won 1–0. But there was more collateral damage: early in the second half, captain Franco Baresi went off injured.

Italy drew 1–1 with Mexico in game three, and Group E ended like this:

Italy sneaked into the next round as one of the four best third-placed teams, having scored one more goal than Norway. They faced Nigeria next, and the pressure was mounting on Italy’s star man. Agnelli had called Baggio a “coniglio bagnato” (wet rabbit) after the Mexico game. Baggio laughed it off, and changed his answer-phone message to say he would return calls “once I have dried my ears.”

He had last scored for the Azzurri in April 1993—a drought that had now lasted fourteen months. His family could see that he was feeling the pressure so, against his wishes, his wife Andreina, daughter Valentina and parents Matilde and Florindo flew to Massachusetts for the Round of 16 game against Nigeria. “He’s a sensitive guy and I could see he needed reassurance. When he saw us, he cheered up,” said Matilde.

Nigeria took the lead, but with two minutes left (and shortly after Gianfranco Zola had been sent off), Italy’s campaign came to life: Roberto Mussi jinked past two defenders, cut the ball back to Baggio on the edge of the area, and he drove the ball home to equalize. Ten minutes later, Baggio scored again, this time from a penalty. He waited for Peter Rufai to take a step to his left then smashed it hard to his right, in off the post.

He scored again in the quarterfinal win over Spain with two minutes left, a dramatic winner from Giuseppe Signori’s lobbed pass to make it 2–1. Then, in the semifinal against Bulgaria, again Baggio was the hero. His first goal was sensational: a run from the left, past two defenders, before curling a shot into the far corner; the second, five minutes later, secured the 2–1 win. Baggio went off with twenty minutes left with a hamstring strain, leaving Sacchi to complain, “It’s a pity he gets himself injured just as he finds his form.”

There were four days until the final. Baggio was injured, Baresi had undergone arthroscopic surgery on his knee, and Italy were without defenders Alessandro Costacurta and Mauro Tassotti, both suspended. There was also the travel factor: their opponents Brazil had played their semifinal in Pasadena’s Rose Bowl, the final venue, while Italy had played in New York and needed a six-hour flight to get to LA.

Baggio did not train for three days and on the morning of the final gingerly tested his leg in the wedding-reception room at Torrance’s Marriott Hotel. Sacchi named the team but was still not sure whether to include Baresi and Baggio. His initial team sheet read:

Pagliuca

Bennarivo

Baresi (Apolloni)

Albertini

Maldini

Mussi

Donadoni

Berti

D Baggio

R Baggio (Signori)

Massaro

Sacchi had made all his players take penalties at the end of every training session. Signori and Baggio had not missed a single kick. Three hours before kick-off, after drinking a coffee, Baggio told Sacchi, “I’m ready to play.”

Brazil hit the post when Pagliuca fumbled Mauro Silva’s shot, Romário dragged wide from four yards, and Baggio had two glimpses of goal, one sliced over, the other hit straight at Claudio Taffarel. “I could have scored but I missed the chances because I was not calm inside myself,” he later said. “In other circumstances and in better physical shape, I’m sure the real Baggio would have made the most of that pass from Massaro. But my World Cup was over when I got injured against Bulgaria.”

The match, played in searing heat, ended goalless. It was the first ever World Cup final to be decided on penalties and it did not go down at all well. “Imagine listening to [Abraham] Lincoln and [Frederick] Douglass debate for two hours and then having them step down from their podiums to decide a winner on belches,” wrote Alex Wolff in Sports Illustrated. FIFA president Sepp Blatter promised it would be “the first final, and the very last” to be decided on penalties, and claimed it was not a sporting way to end such a game. “Football is a collective sport, while penalties are an individual skill,” he pointed out.

Italy gathered in the center circle, and Baggio could sense the tension. “We were all feeling the same before the penalties. We could see the fear in each other’s eyes. When you’re taking penalties, you need to be focused and clear-headed, but we weren’t.”

Baresi kicked first for Italy. His performance had been heroic, especially given the speed of his recovery from injury. Nine years earlier, Baresi had taken two and a half months to recover from the same operation on his left knee; this time he was back on the field in less than four weeks. His penalty flew over the bar. Brazil did not take advantage: Pagliuca saved from Marcio Santos. The next four penalties—from Demetrio Albertini, Romário, Alberigo Evani and Branco—were all scored.

Up stepped Daniele Massaro, the Milan striker who was top scorer for the Italian champions that season. He had also scored twice in the Champions League final, a 4–0 demolition of Barcelona. His form had earned a late call-up, though before the tournament he had not played for Italy for eight years (he and Baresi were the only players who had been part of Italy’s 1982 World Cup-winning squad). Massaro had only recently been converted into a striker: he’d started out in midfield for Fiorentina and as a winger for Sacchi at Milan. Fabio Capello moved him to center forward when he was thirty-one, and he was a popular impact sub whose availability and lack of moaning won the fans over. He called himself soccer’s first aziendalista, or company man, whose motto was always “Put the team first.”

“It was my moral duty to take a penalty,” Massaro recalled almost twenty years later. “I saw some of my teammates try to hide, but I felt I was one of the leaders of that team, and those are the times when you have to prove yourself in front of others. Just before the penalty I didn’t feel so bad, I was pretty confident of scoring. But the next ten seconds, it’s like there’s been a black-out in my mind. Like I lost myself when the kick happened, like it was a dream.”

More like a nightmare. Massaro hit it poorly and Taffarel saved.

“My first feeling was one of surprise. How could I have made such a big mistake? I then felt sorry, not for me but my teammates. But I never felt guilty. Never! You can only make a mistake if you step up in the first place. I’m proud that I took responsibility. No regrets.”

Brazil captain Dunga scored to make it 3–2, and Baggio was next. He was a specialist. He had scored a penalty on his Vicenza debut, when he was just sixteen, against Brescia. He liked to wait for the goalkeeper to move before choosing his corner, and his penalty record—108 goals out of 122 kicks (a success rate of 88%)—remains an Italian record.

He described what happened next in his autobiography, Una Porta nel Cielo (A Goal in the Sky):

At times, you intend to do one thing and another thing happens altogether. I don’t want to exaggerate but I haven’t missed many penalties in my career. And even when I didn’t score, it’s because they were saved, not because I shot over the bar.

This is to make you understand that what happened in Pasadena doesn’t have a simple explanation. When I went to the spot I was relatively lucid—well, as much as you can be in those moments. I knew that Taffarel always dived. I knew him well. So I decided to go down the middle, half height, around half a meter or little more than that, because Taffarel never managed to make saves with his feet. It was an intelligent choice because Taffarel effectively threw himself to his left and he would never have got to the central trajectory that I had in mind. Unfortunately, and I don’t know how, the ball rose three meters and flew over the bar.

Was I up to it? Well, I was the first-choice penalty taker. There wasn’t a reason why I wouldn’t take one. The only players who miss penalties are those who don’t have the courage to take one. That time I missed. It affected me for years. I still dream about it. Getting over that nightmare was difficult.

“Baggio had spent his entire career telling us that poetry in football doesn’t exist in the penalty, but that miss in Pasadena told us a lot of things,” said Vanni Santoni, author of L’Ascensione di Roberto Baggio, a novella that paints Baggio as a sainted figure often talking to God, while Sacchi sits in a chemical bath in Coverciano, Italy’s national training center. “It embodied Italy’s struggle to combine beauty and victory. It portrayed him more than scoring would have done. He came out of it purified.”

It also summed up the many contrasts of his career. Baggio was one of the best players of his generation, yet only ever won a UEFA Cup and a Coppa Italia. He scored in three World Cups, but Italy lost on penalties in all of them. He was a Buddhist, yet obsessed with hunting. Later in his career he took the trouble to write a nine-hundred-page document on how to improve Italian soccer, but resigned from his position at the Italian FA as “President of the Technical Department” after a year. As he whispered during a rare interview in 2013, “It’s true, victory always just eluded me.”

That image of Baggio, hands on hips, looking down at the spot as Brazil burst into celebration, is one of the most iconic in soccer. But for the Italians, Baresi summed up the moment of yet another World Cup elimination on penalties. The warrior-defender could not stop crying, and the more his teammates tried to console him, the more he wept. “He was like a sad baby out there on the pitch,” wrote Giorgio Tosatti in Corriere dello Sport. “After winning so many wars, he lost his last battle. In many years he had never lost control, his cool, his pride. He once played with a broken arm but we never saw his tears despite the huge pain. It was like watching Rambo cry.

“What can you say to such players? What can you say to Roberto Baggio, if he wanted to play and make another miracle for Italy despite the injury, but he missed a couple of chances and a penalty instead? Hadn’t somebody criticized him for not being brave enough? He was certainly brave this time around. What can you say to Massaro, tired to death, if Taffarel saved his penalty? Their pain is just bigger than ours.”

There was no criticism, just sadness, in the days that followed. Over a thousand Lazio fans went to Fiumicino airport to welcome back Beppe Signori, and he hadn’t even played in the final (though he probably should have done).

The idea held that penalties were unfair, and Baggio was adamant that the golden goal, which was introduced in time for Euro 96, or even a replay, would be better. “Does it seem [right] to you that four years of sacrifices come to be decided by three minutes of penalty kicks? Not to me. It’s not right to lose in that way,” he said.*

Massaro doesn’t agree. “It’s true that the best team doesn’t always win, but I really can’t see a better option,” he said. “They are definitely cruel and maybe a bit unfair—but penalties are the only solution.”

As for the theory propagated in Brazil that the spirit of Ayrton Senna, the Brazilian racing driver who had died earlier that year, had lifted the decisive kick into the sky, Baggio was not convinced. “It’s the romantic explanation for a technically inexplicable act. That is, if it wasn’t for my tiredness.”

Massaro is now working as an ambassador for Milan, and he added, “It’s true that because Baggio and Baresi missed, people tend to forget I missed mine too. But there’s a clear reason for that: these guys were among the best Italian players ever. It’s normal people are more interested in talking about them.”

Nevertheless, that did not help him come to terms with his miss. After the final he sat silent in the dressing room for over an hour, and noticed on his return to Italy that no one ever mentioned penalties when he was around. “It was like a taboo subject, a wound that never healed.” Even now, Massaro is still not comfortable talking about it. He still dreams about the moment. “The penalty is with me every day, but the nightmare in my sleep is all about the long walk to the spot. It took me ages to get there from the center circle, and even though it was so hot, I could feel shivers down my back. I have given a lot of thought to what I could have done differently, but I haven’t found the answer. Some say don’t change your mind, others kick it hard and true. The reality is that only those who have taken a penalty in a World Cup final can know what it’s like, and there is nowhere to hide. You just need cold blood and good luck.”

And what about Baggio? Should he have been on the pitch? Should he have taken a penalty? “It’s simple: he was the guy that got us to the final,” said Massaro. “I will always thank him for that because he gave me that opportunity. You don’t see much gratitude in football, but on the day of the final, Sacchi showed the world that he was first a real man and second a football coach. Baggio was in no condition to play, but he had got us there. He had to play. What can you blame Baggio for? He missed his penalty. So? I missed mine. We were brave, we took the responsibility, we didn’t run away. Maybe it seems different from the outside, but these are things that your teammates recognize.”

There might have been another factor behind Baggio’s missed penalty: the fact that he needed to score to keep his team alive. The most significant finding, Geir Jordet believes, in all his analysis is the psychological effect of the “negative valence” kick—in other words, the kick to stop your team from losing.

In his analysis of World Cup, European Championship and Champions League shoot-outs, he noted that the penalty success rate when it came to stopping a team from losing the shoot-out drops to 62%, while the rate to win the shoot-out rises to 92%. Remember Andreas Möller, who was desperate not to take a penalty in the Euro 96 semifinal shoot-out against England, but as soon as he had seen Gareth Southgate miss he ran out of the center circle to take the kick?

James W. Grayson ran an updated analysis, taking into account more recent competitions and over four hundred shoot-out penalties. He got similar results, with a 94% rate “to win” and a 64% “to not lose” rate. “This shows how big the differences are when you put psychology into the mix,” said Jordet. “It basically shows the power of thinking about positive, as opposed to negative, consequences when taking these shots.”*

*

Baggio was one of the best players of his generation; Maradona one of the best of all time. He also missed some key penalties for club and country, including the decisive shoot-out spot kick for Napoli in their 1987 UEFA Cup defeat to Toulouse, and one for Argentina in their shoot-out win in the 1990 World Cup quarterfinal over Yugoslavia (he did score in the semifinal shoot-out against Italy, on his “home ground” in Naples).

Maradona’s most famous penalty record, however, has become a regular refrain among amateur players in Argentina. When a friend of mine missed a penalty in a park game in Buenos Aires, he was told, “Don’t worry about missing that penalty. You know, Diego once missed five in a row!” That’s right, Diego Maradona, the great Diego, failed from twelve yards five times in succession. Francis Cornejo, the man who spotted Maradona as a ten-year-old and was his first coach, recognized his talent but never allowed him to take penalties. He later explained why: quite simply, he wasn’t very good at them.

In the last season of his career, 1996/97, Maradona was back at his former club Boca Juniors, who were trying to build a dream team. Carlos Bilardo was coach and among Maradona’s teammates were Claudio Caniggia, Juan Sebastian Verón and Kily González. The team finished second in the league, but Maradona was left wondering what might have been. “Would we have done better if I hadn’t missed those five penalties in a row during that awful period?” he asked in his autobiography Yo soy el Diego de la Gente (I am Diego of the People). “Those five curses signaled the end of my football career.”

The poor run began on April 13, 1996, against Newell’s Old Boys. Boca were unbeaten but Maradona kicked his penalty wide of Sebastian Cejas’s goal midway through the first half, and two minutes later Hernán Franco scored the only goal of the game to win it for Newell’s. Maradona was taken off with a foot injury, and the crowd booed him as he limped off the pitch. “I went off because it was really painful, but there were some idiots that booed me: they didn’t believe I was injured!”

By June 9, Maradona was fit again, and up against Belgrano. There was another penalty, and this time goalkeeper César Labarre saved it. Labarre barely celebrated—he was worried because Belgrano were playing badly and his team were fighting relegation—and Maradona couldn’t bear to look to the stands, where he knew his wife and daughters would be in tears. Soon it was forgotten: in the same game, he scored an outrageous lobbed goal from the corner of the eighteen-yard box and Boca won 2–0.

On June 9, Boca faced Rosario Central. Maradona was still on penalty duty, but again his effort from twelve yards was saved, this time by Hernán Castellanos. “We won, the team played well, so did I, and we were still in the running for the title . . . but I missed another penalty, the third in a row! It was a disgrace; it was breaking my balls!” Boca won 1–0; later in the game Verón took over penalty duties and also missed.

Two weeks later, Boca welcomed fierce rivals River Plate to the Bombonera. Before the game, River goalkeeper Germán Burgos said he wanted Maradona to take a penalty in the game. “Even if he doesn’t want to take one, I will ask him to do it,” he said. The mind trick worked. Boca were 3–1 up when they won a penalty. Maradona stood over it. Burgos readied himself. The penalty hit the post. Another failure. At least this time the rebound fell to Caniggia who scored for his hat-trick. Boca won 4–1.

The title race with Vélez Sarsfeld was going down to the wire but Boca’s hopes ended on August 7 after a 1–0 defeat to Racing. Once again, Maradona missed from the spot. Boca ended up in sixth place, while Vélez clinched the Torneo Clausura on the last day of the season.

“I wanted to win that title with Boca so badly,” he said. “When I got into the dressing room, I started to cry as I knew that was my last chance. Once we had lost that title, I wanted to kill myself. My family had never seen me so sad. I took responsibility for everything Boca did that year—the good things, yes, but also the bad as well.”

Maradona had once scored fifteen penalties in a row for Napoli; back home, as the light faded on his controversial career, he was struck by what he called “this penalty curse.” “The thing about penalties,” he said much later, “is that they are fifty-fifty. You can get it on target, or you can miss.” If you’re the best player to ever have played the game, though, your chances should be greater than fifty-fifty.

Raúl is another player who fits the Jordet template. By the time he was twenty-three he had won plenty of individual accolades, including (just for 1999/2000) UEFA’s “Best Forward of the Year,” a place in the European soccer writers’ Team of the Year, Champions League top scorer and Don Balón magazine’s Player of the Year.

Spain had gone into Euro 2000 as one of the favorites; they were certainly playing some of the best soccer on the continent, exemplified by a 9–0 win over Austria in qualifying. But their tournament began with a shock defeat to Norway, then a stuttering win over Slovenia, before a miraculous come-from-behind 4–3 victory over Yugoslavia thanks to two goals in injury-time (one from Gaizka Mendieta from the spot).

World champions France awaited in the quarterfinal in Bruges. France took the lead with a curling Zidane free kick before Mendieta, again, scored from the spot. Youri Djorkaeff put France ahead before halftime, and France held on as the clock ticked past 90 minutes. When goalkeeper Fabien Barthez fumbled a back-header near his six-yard line, Spanish defender Abelardo lunged for the ball and tumbled as his foot touched the diving Barthez’s shoulder. It looked like Abelardo had made contact with Barthez rather than the other way around, but referee Pierluigi Collina awarded a penalty.

The problem for Spain was that Mendieta, the team’s specialist, had been taken off. Fernando Hierro, next in line, was on the bench. Real Betis striker Alfonso Pérez wanted to take it, but he was overruled. Raúl stepped up. He was tired, so much so that midway through the second half he had walked toward the touchline, thinking he was being replaced when in fact Ivan Helguera was making way. He had played fifty-seven games for Madrid that season, which included a February trip to Brazil to play in the Club World Cup, and during that time had missed three of his six penalties.

Raúl leaned back as he hit the ball with his left foot and it sailed over the corner of crossbar and post, smashing into the netting that separated the fans from the pitch. As French fans, who had chanted “Vive le coq!” to put him off, celebrated, Pep Guardiola rubbed his beard hard with both hands and Raúl trudged away from the penalty area. There was time for substitute Ismael Urzaiz to head over with the goal gaping. When the final whistle came, so did the tears. Raúl cried on the pitch, and later confessed he cried in the dressing room and in the team hotel. Once again, he had failed to score a decisive goal for his country.

Raúl’s miss was compared to famous Spanish errors in history: Julio Cardenosa, who missed an open goal against Brazil in the 1978 World Cup; Luis Arconada, who let Michel Platini’s free kick slide under his body at Euro 84; Julio Salinas, who squandered a chance against Italy in 1994; and Andoni Zubizaretta, who allowed Garba Lawal’s shot to squeeze in at his near post in the 1998 group-stage defeat to Nigeria. Marca showed a picture of the miss under the headline “It’s all over! Raúl sends Spain’s dream into the clouds,” while ABC blamed the weight of history—“the same as always”—and wrote, “Spain cries with Raúl.” The paper even claimed the national team was cursed and made the link between the venue for the game, Bruges, and the Spanish word for witches, brujas.

The idea that Raúl represented the traditional values of Spain, and was therefore untouchable, was broken only by journalist Diego Torres, who pointed out that the striker had also missed a penalty for Spain Under-21s in their 1996 European Championship final defeat, in a shoot-out, to Italy. “Behind his mask of an introverted and shy kid is hidden a dominant character who intimidates his teammates, and even his coaches,” Torres wrote in El País. “His self-esteem is colossal, fed without a break by uninterrupted success and praise. This was the night of his first great defeat. The first setback for a footballer launched on a geometric progression. A long apprenticeship which maybe had its culmination against France. The real initial test: the one which brings you to disaster or excellence.”

Raúl missed his next penalty as well, in the last minute of a 3–3 draw against Málaga that September, but Real Madrid coasted to the league title and he was top scorer with twenty-four goals.

But Bruges summed up Raúl’s misfortune at major tournaments: he had ended the 1998 World Cup as a substitute, was injured and missed the 2002 World Cup quarterfinal loss to South Korea, and at Euro 2004 was blamed for Spain’s group-stage elimination after defeat to Portugal. His presence in the side, as a number 10, meant that Juan Carlos Valerón and Xavi Hernández were left on the bench. “Nobody personifies Spain’s failure better than Raúl,” wrote El País. His status had held the team back.

When he was dropped from the Spain squad in September 2006 for the first time in ten years, there was an outcry from the Madrid press. “He is a big star but to keep talking about it is ridiculous,” moaned coach Luis Aragonés. Raúl never played for Spain again, despite the calls, even just before Euro 2008, for his inclusion. Aragonés got it right: Spain won the tournament thanks to Cesc Fabregas, who was selected instead of Raúl.

*

What do the stories of Baggio, Maradona and Raúl have in common? The players all missed, but it was the coach who took the flak for them. There are differing views as to how much responsibility a coach can take for a missed penalty, but it’s easy to forget that in any penalty situation, and especially a shoot-out, the stress is not just on the player. The coach is the one whose career lives or dies by the result. A player won’t lose his job after a shoot-out defeat. A coach might.

“It doesn’t happen just like that, you brainstorm who your penalty takers will be for months in advance,” said Aimé Jacquet, whose France team beat Italy in a quarterfinal shoot-out on their way to winning the 1998 World Cup.*

Jacquet gave an interesting insight into the psychology of the coach in this situation. “It’s better to be direct, there’s no time for the guys to think. The players are tired, the game has taken a lot out of them. It’s the coach’s responsibility to make the arrangements. So you never ask, ‘Will you take one?’ That’s the worst. I say, ‘You, you, you, you and you: one, two, three, four and five.’ The player has the hard job: to take the penalty. So you must make it easy for him.”

In other words, the coach has to manage his status players. Before the penalties against Italy, one of Jacquet’s chosen five, Youri Djorkaeff, specifically asked not to take one as he felt that Italy’s goalkeeper, his Inter Milan teammate Gianluca Pagliuca, knew his patterns too well. Jacquet said it was fine and smiled, because he didn’t want to worry the others.

He knew at this stage that two of his most senior players, Deschamps and Marcel Desailly, also did not want to take a spot kick. As the pair stretched alongside each other, Marcel turned to his teammate and said he should take a penalty before him. “You’re the captain, it’s your responsibility.”

“But you’re a defender, you’ve hardly run, and I’m knackered,” came the reply.

As it was, Jacquet had his five, and had told Fabien Barthez he would be next if it went to sudden death. Barthez’s goalkeeping coach Philippe Bergeroo told him, “We have been studying the Italian kickers—” Barthez cut him off and said, “I don’t want to know anything.” He was a goalkeeper who preferred to rely on his instinct. “That’s the best way to be,” agreed Laurent Blanc.

Each team’s star men went first—Zinedine Zidane for France, Roberto Baggio for Italy—and scored. Both kicks were significant. Zidane always went the same way, to his natural side, but had complete trust in his ability. “I don’t know if it helped me or not but I always knew where I was going to shoot,” he said. “I never even asked myself the question. If I hit it right, the goalkeeper could not stop it.” That was regardless of the level of tension as well. Against England in Euro 2004, France were awarded a late penalty with the score at 1–1, and Zidane spotted the ball and then crouched down, holding his ankles with his hands. The referee blew, Zidane stood up, seemed to scratch his nose, took a pause before beginning his run-up and scored, kicking to his usual side. The replay showed that Zidane was crouching down because he had been vomiting heavily on the edge of the area.

“For most of us, the question would be, ‘How do you deal with that?’” Jordet remarked. “That’s when players are more likely to fail and they will do stupid things, like rushing to get it over with quicker. It’s OK for Zidane to have the discomfort but it is his response to it, the fact he’s saying ‘I have to do this, so that’s what I’m going to do,’ which is spectacular.” Jordet and I had just watched the vomit video in his office. “Even when he throws up, he’s gracious,” said the Norwegian commentator.

Back to Jacquet, one of whose dilemmas, once he had told the two twenty-year-olds Thierry Henry and David Trezeguet that they would be taking penalties, was the right order. “I thought about going: experience, youth, experience, youth.” Instead, he picked Bixente Lizarazu to go second. His poor kick was saved. Lizarazu usually kicked third in shoot-outs, and Jacquet blamed himself. “I think he was upset, and I felt a bit guilty when I thought about it afterward.”

Barthez saved from Demetrio Albertini, then the teams exchanged goals until Blanc stepped up, fifth for France. He scored, and as Luigi di Biagio walked toward the spot, French full back Vincent Candela turned to his teammates on the touchline and said, “He’s going to miss.” He was right: di Biagio hit the crossbar, France were through, and the brainstorming had taken Jacquet another step closer to winning the World Cup on home soil.

There was redemption for di Biagio, though. Two years later, he stepped up for Italy in their Euro 2000 win over Holland. “I played a great tournament in 1998 and was certain I’d score that penalty against France,” he told RAI TV show Sfide. “But I missed, and when I stepped up against Holland, I was shaking with fear.” Di Biagio had promised his wife the night before the game that he would not take a penalty, and just before he walked to the goal, Totti turned to him and said, “Don’t worry about being scared, it’s normal. Have you seen how big van der Sar is?” Di Biagio was intimidated by the orange-clad fans behind the goal and as he spotted the ball he had no idea how he was going to take it or where he was going to put the ball. He went for precision over power and scored. “It was an amazing feeling. The only thing I don’t like is that di Biagio will always be remembered for the mistake in 1998, not for that penalty scored two years later. But I guess that’s normal.”

When Marcello Lippi led Italy to victory in the 2006 World Cup final on penalties, it was the third shoot-out in a final that he had been involved with, and he predicted the correct outcome before each of them. His first was with Juventus in the 1996 Champions League final against Ajax. “I could see my players were desperate to contribute to the victory. With their eyes, they were telling me: ‘Let me take one.’” It was a different story seven years later, when Juventus faced AC Milan in the Champions League final at Old Trafford. “When I was picking the five, all the players were looking in the stands, searching out their wives or girlfriends, or focusing somewhere else. I said, ‘Guys, they don’t allow me to take a penalty, you have to take them.’ So I don’t think it was a coincidence that we lost.”

Against France in 2006, Lippi knew his five before the game: Pirlo, Materazzi, de Rossi, del Piero and Totti. But Totti had gone off and Lippi had to choose another player. He turned to Fabio Grosso.

“You take the fifth penalty.”

“Why me?”

“Because you are the best man in the last minute,” replied Lippi, referring to the injury-time penalty Grosso had dubiously earned against Australia and the late winner in the semifinal over Germany.

“I think those words gave him some extra confidence,” Lippi said.

Lippi’s choice of Grosso was a good example of picking the person over the player; he could have pointed at a bigger name—Fabio Cannavaro, Gennaro Gattuso, Luca Toni and Vincenzo Iaquinta were all available—but he felt that a player of lower status would do the job.

“I was astonished when he asked me,” Grosso admitted. His last penalty had been five years earlier in Serie C2, Italy’s fourth division. “I don’t remember my penalty very well: my run-up, the way I hit the ball, nothing’s very clear. I just remember having a huge responsibility, and I forced myself to maintain my calm inside.

“Experience counts for nothing in moments like that. Of course you have to have the technique but above all it’s about reaching a very specific mental state in the seconds preceding the shot. I will always remember that I ended a curse, the curse on Italy for penalty shoot-outs and extra time: there was the 1994 World Cup final, the 1998 quarterfinal, Euro 2000. The same thing worried us before the final but this time we had the resources to stay calm. Lippi helped transcend us with his confidence.”

On the evening before the game, France coach Raymond Domenech had watched Trezeguet and Sylvain Wiltord practice their penalties. He’d laughed and told them, “Of course you’re going to score if you take one now; but what about tomorrow, when you’re tired, eighty thousand people are in the stadium and the World Cup is at stake?” Trezeguet insisted that he still wanted to practice. Wiltord scored. Trezeguet scored. “Enough now,” Domenech said. “Do that again tomorrow and we’ll be happy.”

It didn’t quite turn out like that. Pirlo, Wiltord and Materazzi all scored so Italy were 2–1 up when Trezeguet stepped up to face Buffon, his teammate at Juventus. Buffon had conceded a Panenka to Zidane earlier in the match and was not feeling at all confident. “I was not in tune with what was happening; it seemed to me that France could have taken two thousand penalties and scored all of them.” Trezeguet knew that Buffon was used to facing his penalties (the pair would practice after training sessions at Juventus) so he aimed for one of the toughest areas of the goal: the top left corner.* He hit it wide, while Buffon had dived the other way. “For me, it was a logical consequence of the fact that he had played for several years with Buffon at Juventus and thought he knew where he was going to shoot,” said Willy Sagnol, who stepped up for France’s fourth penalty.

Sagnol did not want to take it, and he remembers Domenech saying to him, “You shoot.” But he was not sure if it was a question or a statement. “I said yes as naturally as I could but then I doubted myself and said, ‘Ach, it’s too late now.’ It’s important to have an ego as a player, and to know how to control that in a World Cup final.”

The French players returned home empty-handed, but they were greeted as heroes. A homecoming parade was organized, and as the players emerged one by one on to the balcony of Hotel Crillon, on the Place de la Concorde, Trezeguet was in tears, and was supported by Thierry Henry. Trezeguet considered his appearance on the balcony a major achievement: “It showed I was strong mentally.”

This penalty miss did not define his career, partly because Trezeguet had scored France’s golden goal winner in the Euro 2000 final against the same opposition and partly because France overachieved in reaching the 2006 final. Years later, Trezeguet told Canal Plus that his relationship with Domenech was complicated. “I did not feel important. I felt that the technical staff had no trust in me at that time.”

Again, this ties in with the question of status and hierarchy in the squad. Trezeguet did not feel enough support, yet Domenech trusted him to take a penalty in the World Cup final. The coach’s job is to prepare the players to perform at their peak. In a shoot-out, that means leaving as little as possible to Lady Luck.