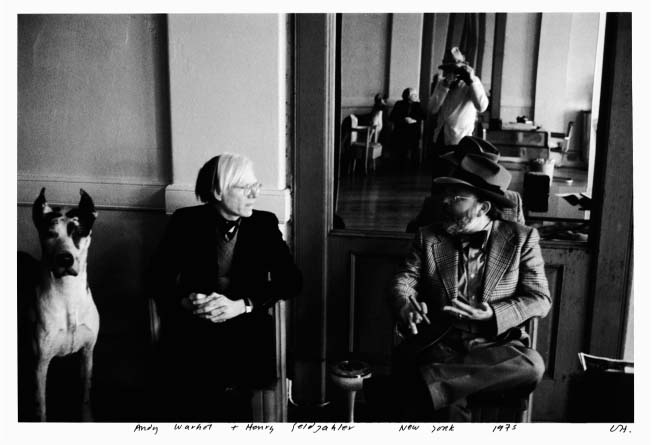

Aboard the jetliner that was flying me out to Los Angeles a few months back, I was browsing through a recent book by David Hockney, the forty-six-year-old British-transplant Californian whose newest work I was heading out to see. Or not so much a book as a pamphlet, the artist’s textual accompaniment to an exhibition he’d organized at the National Gallery in London back in 1981. The National Gallery has lately been sponsoring a series of exhibitions under the rubric The Artist’s Eye, in which contemporary artists are invited to select a group of masterworks from the museum’s own bounteous collections and to comment on why these particular paintings have been especially important to them. For his turn, Hockney selected a Vermeer, a Piero della Francesca, a Van Gogh, and a Degas. A few years earlier, Hockney had composed a painting of his own (Plate 2) in which he portrayed his friend, the curator Henry Geldzahler, thoughtfully looking at reproductions of these very paintings taped to a screen in his studio, and he now included this work in his small show as well. In his catalogue essay, Hockney celebrated the exquisite richness of the experience of looking at such paintings, especially when compared with the damning poverty of the experience of looking at most ordinary photographs. With a certain irony, he suggested that the only thing photography was much good at conveying—or at any rate, conveying truthfully—was another flat surface, as, for example, in the reproduction of a fine painting. “About sixty years ago,” he concluded, “most educated people could draw in a quite skillful way. Which meant they could tell other people about certain experiences in a certain way. Their visual delights could be expressed. . . . Today people don’t draw very much. They use the camera. My point is, they’re not truly, perhaps, expressing what it was they were looking at—what it was about it that delighted them—and how that delight forced them to make something of it, to share the experience, to make it vivid to somebody else. If the few skills that are needed in drawing are not treated seriously by everybody, eventually it will die. And then all that will be left is the photographic ideal which we believe too highly of.”

Hmmm, I remember thinking as the seat belt signs came on and I stowed my satchel for the descent into Los Angeles, that last comment seemed a bit odd, since about the only thing Hockney had been doing in the two years since was taking photographs—tens of thousands of photographs—and it was indeed Hockney’s photographic work which this jet, landing, was now delivering me to see.

I rented a car at the airport, drove to my hotel at the base of the Hollywood foothills, deposited my bags, phoned Hockney, and within the hour was driving up Laurel Canyon toward the artist’s home. At the top of the canyon, the road intersects Mulholland Drive, onto which I now turned—a long meandering avenue that casually skirts the crest of the Hollywood Hills, heading west to east, bobbing in and out of canyons where dusty chaparral outcroppings give way to wide valley vistas far below (a drive vividly evoked, as it happens, in one of the last major paintings Hockney had undertaken before being swallowed into his photographic passion (Plate 1). About two miles east of Laurel Canyon, I veered onto Hockney’s side street and quickly parked the car. The home where Hockney has been living since 1979 is nestled below street level, and one arrives at the front door by walking down cement steps shaded in foliage. As I rang the doorbell, I could see through a narrow window into the living room–studio—a delirious clutter. Poster boards were leaning against every available vertical, their faces brimming with layers upon layers of photoprints. Hockney was standing in front of a large table, a thick deck of photoprints in his hand, staring down at a poster board collage-in-the-making, lost in thought. He’d posit a print, look at it for a moment, move it over, finger another print a few inches to the side, pick it out of the jumble and relegate it to one of the many piles of photoprints surrounding the board. Then he’d revert to his even concentration, his game of photo solitaire, utterly oblivious. I rang the bell again, and again, until finally he looked up, awakened, and came to the door, smiling, to let me in.

“I’m sorry,” he said with genuine concern. “Were you waiting here long?” His face was friendly and congenial, his round features reemphasized by round glasses (the left frame gold, the right one black). Pyroxide blond hair shagged out from beneath a yellow-and-red checkered cap across which was emblazoned the word California. He wore a skinny loosened burgundy tie, a red-striped shirt, a green smock, a pair of well-worn gray wool slacks, and black-and-white checkered slippers over mismatched yellow and red socks. He was of average height but, as he led me now through the living room, I noticed that he lumbers along with the comfortable slouch of a tall man. Leaving the entry foyer, I peered down the hallway into the next few rooms, noting how each wall had been painted a different brilliant color. The afternoon sun streamed in, bouncing hue off hue, to simultaneously cooling and luscious effect. Hockney mentioned that the rooms had only recently been painted and then excused himself for a moment, returning to his collage. He made a few more adjustments, lifted another print out of the middle, set it aside, slid in a replacement, and said, “There, that will do for the time being.” He then looked up and led me out through the sliding glass door onto the shaded blue-painted wood deck.

Only here does one get a sense of the layout of the house—a curving amphitheater of rooms overlooking (in place of the stage) a modest bean-shaped pool. A few months back, Hockney drained the pool and applied playful navy blue brushstrokes to its aqua bottom: this afternoon, refracted, the strokes seemed to lollygag on the surface of the water—hedonist amoebas. Beyond the pool, high ferns and bushes blocked any view of the neighboring houses.

Leaning now against the deck railing, looking back through the sliding glass doors at the piles of photos scattered about the room, I mentioned my airplane reading and asked Hockney what he was doing at this point taking photographs at all. “Ah well,” he replied impishly. “You mustn’t overinterpret those comments. It’s not that I despised photography ever, it’s just that I’ve always distrusted the claims that were made on its behalf—claims as to its greater reality or authenticity. Actually, I’ve taken photographs for years—snaps, I’d call them, pictures of friends and of places we’d visit. When I’d get home I’d put the pictures in albums. Since the midsixties I’ve managed to fill several each year. During some periods I was more involved than others. I mean, clearly, all along I’ve had an ambivalent relationship to photography—but as to whether I thought it an art form, or a craft, or a technique, well, I’ve always been taken with Henry Geldzahler’s answer to that question when he said, ‘I thought it was a hobby.’”

Beginning in 1968, Hockney often used photography as an aide-mémoire in his painting. Several of his most famous portraits—for example, Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, 1968, or Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy 1970–71—were preceded by dozens of photographic studies, alongside the many pen-and-ink sketches. He’d photograph the furniture, the walls, the way light fell across the room at different times of day; details of faces, hands, limbs; impressions of stances and postures. Photorealism had come into vogue during that period, but Hockney wasn’t interested in achieving a photographic likeness—a painting which would look “as real as a photograph” (many photorealist paintings had in fact been traced onto the canvas from the projected slide of a photograph). Rather, he was using the photographs to jog his memory; the confluence of dozens of discrete recollections and observations would form the eventual painting, which would distill the essence of all the studies that had preceded it. By using photographs in this way Hockney, if anything, came to distrust their purported reality all the more.

“I mean, for instance, wide-angle lenses!” Hockney exclaimed as we stood that afternoon on the deck overlooking his pool. “After a while I bought a better camera and I tried using a wide-angle lens because I wanted to record a whole room or an entire standing figure. But I hated the pictures I got. They seemed extremely untrue. They depicted something you never actually saw. It wasn’t just the lines bending in ways they never do when you look at the world. Rather it was the falsification—your eye doesn’t ever see that much in one glance. It’s not true to life.”

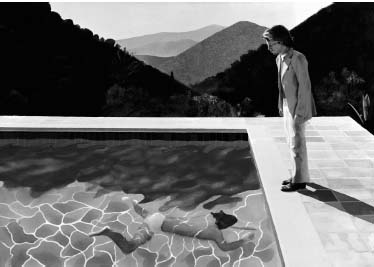

To get around this problem, Hockney began making “joiners.” For example, when he needed a photo of his friend Peter Schlesinger standing, gazing downward, as a study for his Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972, he took five separate shots of Peter’s body—head and shoulders, torso, waist, knees, feet— and spliced the prints together, effecting the closest possible overlap (Figs. 1 and 2). “At first I was just going through all this because the result, the depiction of the particular subject, came out looking clearer and more true to life than a single wide-angle version of the same subject,” Hockney explained. “However, fairly early on I noticed that these joiners also had more presence than ordinary photographs. With five photos, for instance, you were forced to look five times. You couldn’t help but look more carefully.”

FIG 1 David Hockney, Peter Schlesinger, London, 1972

FIG 2 David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972.

Throughout the seventies, Hockney continued to take photos, as studies or mementos, but with little interest in the medium itself. Dutifully, he’d have his assistants enter the prints into his ever-expanding shelf of albums (by the early eighties more than 120 of them), but he was utterly careless with the negatives, tossing them, unsorted, into boxes. Hockney’s apathy notwithstanding, other people were becoming quite interested. “The Pompidou Center in Paris kept nattering away at me for years to do a show of the photos,” Hockney recalled, “and I kept putting them off. I wasn’t interested: most photo shows are boring, always the same scale, the same texture. But they kept insisting—they said they wanted to do it because I was a painter, and so forth. Finally, in 1981, I gave in, but I told them they’d have to come and make the selection themselves because I didn’t have a clue. So, early in 1982, the curator Alain Sayag arrived here and spent four days looking through the albums, making his selection, and for four nights we sat here arguing about whether photography was a good medium for the artist.

“My main argument was that a photograph could not be looked at for a long time. Have you noticed that?” Hockney led me back into the studio and picked up a magazine, thumbing through randomly to an ad, a photograph of a happy family picnicking on a hillside green. “See? You can’t look at most photos for more than, say, thirty seconds. It has nothing to do with the subject matter. I first noticed this with erotic photographs, trying to find them lively: you can’t. Life is precisely what they don’t have—or rather, time, lived time. All you can do with most ordinary photographs is stare at them—they stare back, blankly—and presently your concentration begins to fade. They stare you down. I mean, photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralyzed cyclops—for a split second. But that’s not what it’s like to live in the world, or to convey the experience of living in the world.1

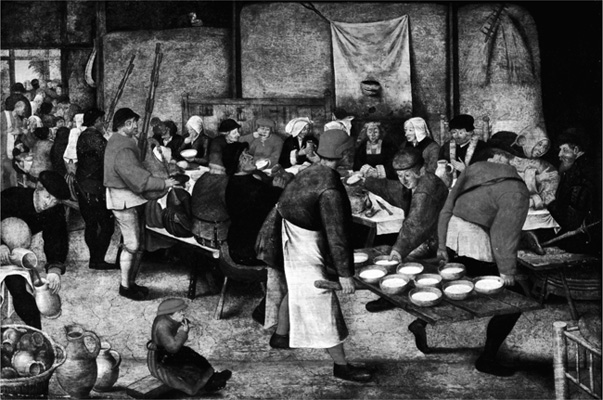

“During the last several months I’ve come to realize that it has something to do with the amount of time that’s been put into the image. I mean, Rembrandt spent days, weeks, painting a portrait. You can go to a museum and look at a Rembrandt for hours and you’re not going to spend as much time looking as he spent painting—observing, layering his observations, layering the time. Now, the camera was actually invented long before the chemical processes of photography—it was being used by artists in Italy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the form of a camera obscura, people like Canaletto, who used one in his paintings of Venice. His students would trace the complicated perspectives of the Grand Canal onto the canvas, and then he’d paint the outline in, and the result would appear to confirm the theory of one-point perspective. But in terms of what we’ve been talking about, it didn’t really matter, because the entire process still took time, the hand took time, and though a ‘camera’ was used, there’s no mistaking the layered time. At a museum you can easily spend half an hour looking at a Canaletto and you won’t blank out.

“No, the flaw with the camera comes with the invention of the chemical processes in the nineteenth century. It wasn’t that noticeable at first. In the early days, the exposure would last for several seconds, so that the photographs were either of people, concentrated and still, like Nadar’s, or of still lifes or empty street scenes, as in At-get’s Paris. You can look at those a bit longer before you blank out. But as the technology improved, the exposure time was compressed to a split second. And the reason you can’t look at a photograph for a long time is because there’s virtually no time in it—the imbalance between the two experiences, the first and second lookings, is too extreme.2

“Anyway,” Hockney concluded, “Sayag and I spent four nights having these arguments, and in the daytime he made his selection.” The trouble came when it was time to find the negatives amid the many boxes so that proper reproductions could be made. “There was no way they were going to find them in four days, so instead we went down to the store and bought several cases of Polaroid SX-70 film and came back up and photographed the prints Sayag had selected so that he could go back to Paris and prepare the show.” The curator left, the negatives were eventually ferreted out, and by summer 1982 the Pompidou Center was indeed running a highly successful show entitled David Hockney Photographs.3 Meanwhile, back in Los Angeles Hockney was left with several dozen packs of unused Polaroid film.

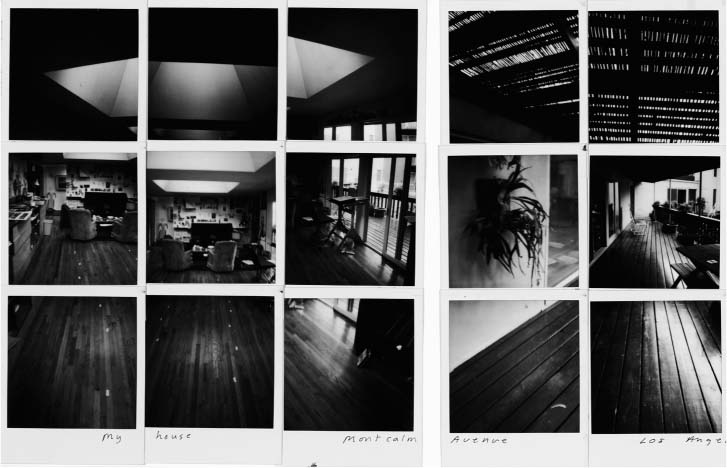

FIG 3 David Hockney, My House, Montcalm Avenue, Los Angeles, Friday, February 26th, 1982.

He began almost immediately. The morning after Sayag left, Hockney loaded his Polaroid and started on a tour of his house, snapping details (Fig. 3). Beginning in the living room (which at the time was much less cluttered—indeed, one imagines that this was to constitute a record of the very last time it would be that uncluttered), he cast three views of the floor, moving left to right, then three views of the middle distance, and then three views of the ceiling with its lovely skylight. There was no attempt to effect the exact matching that had characterized his earlier joiners. Indeed, the two chairs that appeared in one of the middle-distance shots appeared again in the next, but as if closer and from a slightly different angle. (The parallel beams of hardwood in the floor emphasized the different perspectives.) The third middle-distance view included the sliding glass door and, through it, the deck. He then went out onto the deck, repositioned himself, and shot another series of images with new perspectives but similar repetitions. In the corner of the rightmost of these middle-distance images could be seen the top of a staircase leading downward. Repositioning himself once again, leaning out over the edge of the balustrade, he shot still another series, this time of the steps and the garden and pool toward which they led.4

Already as he was shooting the individual Polaroids, he was arranging them into a composition, laying the square SX-70 prints side by side, reshooting perspectives where the images didn’t quite meld or where the articulation of space became confused. “Very early on,” Hockney subsequently reported, “I realized that if the pictures weren’t clear enough, and if their relationship to each other wasn’t clear enough, the collage ended up looking like a jigsaw puzzle and your eyes literally couldn’t stay on it.” By the time he was through, he’d created a rectangular panel consisting of thirty individual square images, arrayed in a grid (three high and ten wide), which uniquely conveyed the experience of walking through that house from the living room onto the deck, down the stairs and toward the pool. Yet this movement was not conveyed in traditional comic-book style or in the staccatocinematic mode of Eadweard Muybridge, where each new frame implied a new episode or another staggered step. Rather, the entire panel reads as an integrated whole, as a house, a home, through which the viewer was invited to move, from inside to outside and then back. Indeed, that’s what this collage finally looked most like—the very experience of looking as it transpires across time.

Hockney glued the thirty Polaroids down onto a panel and then inscribed a title across the white borders of the bottom ten squares: My House, Montcalm Avenue, Los Angeles, Friday, February 26th, 1982. And he was off: during the next three months he would compose over 140 Polaroid collages. By summertime they would be the focus of three separate exhibitions—in New York, Los Angeles, and London. A couple of them would even be included at the Pompidou Center show in Paris.5

“From that first day,” Hockney recalls, “I was exhilarated. First of all, I immediately realized I’d conquered my problem with time in photography. It takes time to see these pictures—you can look at them for a long time, they invite that sort of looking. But, more importantly, I realized that this sort of picture came closer to how we actually see, which is to say, not all at once but rather in discrete, separate glimpses, which we then build up into our continuous experience of the world. Looking at you now, my eye doesn’t capture you in your entirety, but instead quickly, in nervous little glances. I look at your shoulder, and then your ear, your eyes (maybe, for a moment, if I know you well and have come to trust you, but even then only for a moment), your cheek, your shirt button, your shoes, your hair, your eyes again, your nose and mouth. There are a hundred separate looks across time from which I synthesize my living impression of you. And this is wonderful. If, instead, I caught all of you in one frozen look, the experience would be dead—it would be like . . . it would be like looking at an ordinary photograph.”

No sooner had Hockney achieved his breakthrough with his tour-of-the-house collage than he began training his Polaroid on people. Indeed, people, carefully observed, became his preferred subject—or rather, perhaps, continued to be his preferred subject. “There are some lines in Auden’s ‘Letter to Lord Byron,’” Hockney commented to me that afternoon, as we began looking through a box of 8-by-10-inch reproductions of his Polaroid collages, “which I’ve always particularly fancied:

To me art’s subject is the human clay,

Landscape but a background to a torso.

All of Cézanne’s apples I would give away,

For a small Goya or a Daumier.

I mean, I don’t know about those particular apples—Cézanne’s apples are lovely and very special—but what finally can compare to the image of another human being?”

By the end of his first week of voracious experimentation, Hockney had already achieved what would prove one of the most fully realized collages in the entire series, a warmly congenial portrait of his friends Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (Plate 3). The two emerge from a grid of sixty-three Polaroid squares, nine high by seven wide. Isherwood, the aging master, is seated, a wineglass in his hand and a cheerful gleam in his eye, which is trained upon the camera. The younger Bachardy stands, leaning against the wall and looking down affectionately at his longtime friend. Isherwood’s head is basically captured in one square still, but Bachardy’s hovers, in a play of movement that fans out into five separate squares—that is, five separate vantages, five separate tilts of the head, five distinct moments of friendly concentration. Bachardy’s five heads give the impression of a buzzing bee bobbing about Isherwood’s still flower of a face. Yet the five vantages read, immediately, as one head; and indeed, a head no larger than Christopher’s. If anything, Isherwood’s face is the center of attention, the fulcrum of the image.

“With this one of Christopher and Don I started with their faces, just as I always do in drawings and paintings,” Hockney recalls. “But I’ve noticed with these collages that you almost always end up throwing out the first pictures of faces: they’re too self-conscious and stiff. Afterwards, when you’ve been spending time snapping elbows and legs” (the vantages that include Bachardy’s legs seem tilted so as to emphasize his height—one square foreshortens his leg from knee all the way to floor, whereas another, a few squares over, consists of nothing but Isherwood’s huge kneecap), “then you can go back to the face, which in the meantime has calmed to a more natural aspect. In this case at first they were both looking at me, but as the minutes passed, I noticed that Don spent more and more time gazing down at Christopher with that fond, caring look that so characterizes their relationship. So the piece changed as I was making it.”

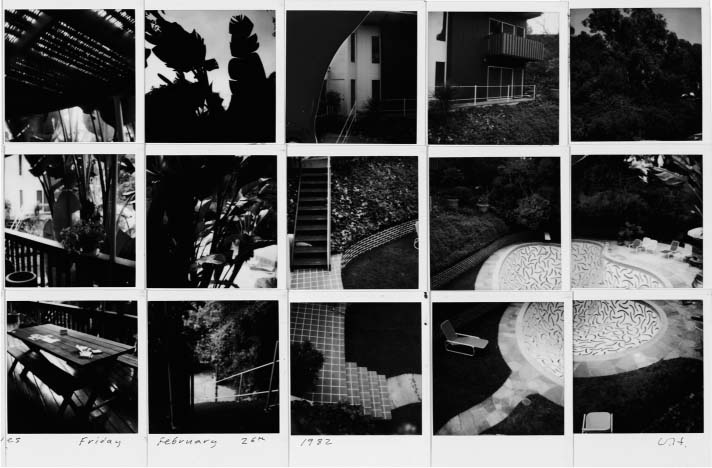

FIG 4 David Hockney, Andy Warhol and Henry Geldzahler, New York, 1975.

Back in 1975, by way of contrast, Hockney had snapped a photo of his friend Henry Geldzahler, cigar in hand, making an animated point in a conversation with Andy Warhol (Fig. 4). The two were seated, facing each other, and a Great Dane stood guard at Warhol’s side, facing the camera. Behind Warhol and Geldzahler was a mirror, in which you can see Hockney standing, taking the picture. Behind Hockney was another mirror, where again you can see the conversationalists and the dog, only smaller. Strangely, it’s only in this second reflection that you notice that the dog is not real: it’s stuffed. And looking back at the figures of Geldzahler and Warhol, you can’t really tell the difference. “That’s the whole point,” Hockney confirms. “In ordinary photographs, everybody’s stuffed.” In this new portrait, however, Isherwood and Bachardy are anything but stuffed. Theirs is a living relationship: it’s living right there before your eyes.

FIG 5 David Hockney, Stephen Spender, April 9th, 1982 (detail).

“It took me over two hours to make that collage,” Hockney explained. “I’d snap my details, spread them out on the floor while they developed, and go back for more. Christopher said I was behaving like a mad scientist, and there was something mad about the whole enterprise. Looking back at the completed grid, it seems as if each shot were taken from one vantage point—there is, as it were, a general vantage—but if you look more closely, you can see that I was moving about all over. The lens on a Polaroid camera is fixed: you can’t add close-up or zoom lenses or anything. So that to get a close-up of the floor, I had to get close up to the floor. In this other one here, of Stephen Spender” (Hockney pulled out a reproduction of a remarkable composite portrait with the writer seated in the foreground and the living room–studio receding into the background), “I spent so much time in the back of the room, behind Stephen’s chair, that finally he exclaimed, ‘Are you still taking my picture, David?’ [Fig. 5]. Or, in this one here” (Hockney showed me the reproduction of a collage of his darkened bedroom in the morning, the light just beginning to filter through the Levellor shades, all seen, apparently, from a vantage point at the head of the bed, the viewer still under the covers, a magazine by his side), “it looks like I just woke up, rubbed my eyes, picked up the camera and started snapping away, never leaving the cozy sheets; but in fact I had to get up and walk over to the bookshelves, the window, all around, to slowly build up the image.6

“This one here,” he said, pulling out a reproduction of a smallish collage, a grid five by five, of his London dealer John Kasmin, smoking a cigarette, “took a very long time to shoot. Kas ended up having to smoke ten cigarettes! I kept on getting the line of his face wrong. It didn’t look like him—or my sense of him. I took more than twice as many pictures as I finally used. Similarly, with this other one here of Kas sitting in a blue chair, I kept having to rephotograph the chair to get it right. As it turned out, the chair looks much larger than it actually is, but that’s because it seemed that way, with Kas sitting in it. The same thing happens with the leafy tropical plant next to Stephen Spender in the other collage: it’s much larger than it actually is, but that’s because I got interested in it. Relative importance, not accuracy, was what I was trying to convey. Which is to say, the entire process was just like drawing.”

The exhibitions of these Polaroid collages, when they were mounted a few months later, would be called Drawing with a Camera. Assay and correction, approximation and refinement, venture and return. “The camera is a medium is what I suddenly realized,” Hockney explained. “It’s neither an art, a technique, a craft, nor a hobby—it’s a tool. It’s an extraordinary drawing tool. It’s as if I, like most ordinary photographers, had previously been taking part in some long-established culture in which pencils were used only for making dots—there’s an obvious sense of liberation that comes when you realize you can make lines!” And for all their beauty as color-saturated objects (Hockney, as ever, is an extraordinary colorist; he somehow manages to coax colors out of the Polaroid film you’d never have imagined were in there), these collages are principally about line. An internal sleeve crease, for example, aligns in the next frame with the outer sleeve contour, and contours generally jag from one frame to the next, a series of locally abrupt disjunctions merging into a wider coherence.

FIG 6 David Hockney, Arnold, David, Peter, Elsa, and Little Diana, 20th March 1982.

There is in some of these collages, as in some of Hockney’s finest pencil drawings, a remarkable psychological acuity at work. In the Spender combine, for example, the face itself develops out of six squares—three tall and two wide—alert, inquisitive, probing to the left, and to the right, tired, weary, resigned. Spender, Hockney seems to suggest, contains both aspects. About the same time, Hockney contrived a poignant study of his housekeeper Elsa with her four children, grouped around the kitchen table (Fig. 6). Little Diana peers out at the camera, adorably, from her mother’s lap. Her mother, meanwhile, is looking over to the side at her second-oldest son, who is looking back benignly at her. Her youngest son is looking calmly out into space, a hint of a smile playing across his cheeks. Each of the faces exists serenely whole, centered in its respective square: a great, soft, uncomplicated calm recirculates lovingly among them. Only the oldest son, standing in the middle, his lean body taut and his hands shoved in his pockets, seems to exist apart: his face is divided between two squares, and his gaze seems more complex, anxious, intent, as if in growing, he is growing out of this simple household. He is as divided as his face.

FIG 7 David Hockney, Mother, Bradford, Yorkshire, 4th May 1982.

In another treatment of the same theme of mother and children Hockney trains his gaze on his own mother as she sits in the living room of her home in Bradford, Yorkshire (Fig. 7). (The grid consists of 112 squares, sixteen tall by seven wide.) Her paisley dress seems to blend into the floral rug: she almost disappears into the camouflage, except for her hands, folded mildly in her lap, and her thoughtful face, which emerges from a six-square rectangle (three tall by two wide)—you can almost see the thoughts moving slowly from one square to the next. Just over to the side of her head, resting on a table in the back of the room, bounded in a single square of this massive collage, is a framed photograph of her five children as youngsters (David among them). The photograph reads almost as a caption bubble: what she is thinking.

In other collages, there is an almost puckish sense of play. This is especially true of Hockney’s repeated treatments of his pool, where more than anywhere else, his collage technique reveals its elastic possibilities: Silly Putty vision. Since he can frame as many details as he likes on his way to making his collages, he can alter the shape and size of the pool at will. In one collage, Nathan Swimming, the lima bean shape is smoothed out to a more regular ovoid, and Nathan’s arms push forward in an aerodynamically sleek reach. His activity of swimming seems to take up the entire collage: it’s as if the pool is only one lazy push-and-stroke from end to end. In the huge collage Gregory Swimming, by contrast, Hockney has ballooned the turquoise waters to Olympic proportions. (The collage consists of 120 squares in a rectangle eight high by fifteen wide, and on all sides the pool extends right up to the edge.) Gregory, naked, is everywhere—arms, legs, head, bottom—a polymorphous carousel of sensuality, a carp pool boiling over with delight. “I sort of see this one as my version of a Tiepolo ceiling,” Hockney says, smiling, “you know, those baroque vaults with all the little chubby angels ascending high into the blue, blue sky.”

Although within days of setting out, Hockney was already making some of the finest collages in the series, there was still a progression in his technique and style across the three months of his Polaroid passion, which was perhaps most evident in the size of the collages. Starting out fairly small (that first panel had consisted of a mere thirty squares), he quickly progressed to collages of over a hundred squares, and the complexity of vision had everything to do with the scale of the collages. (The largest of all, The Printers at Gemini, consisted of 187 squares—eleven tall by seventeen wide—and took more than three hours to complete. It portrays seven figures and, along the wall in the background, some of the lithographs these artisans produced, including works by Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, and Hockney himself.)

By the end of the Polaroid series, however, Hockney had so mastered his technique that he could radically reduce the scale of his collages while sustaining the complexity of images he’d attained in the largest works. Thus the masterpiece of the entire series is arguably one of the last collages, a composite of Noya and Bill Brandt consisting of forty-nine squares, seven by seven (Plate 5). In early May, encountering the distinguished British photographer in a London restaurant, Hockney invited him and his wife to pay a call at his Pembroke studio. A few days later, when the couple took up the invitation, Hockney attempted a portrait. The collage, as usual, changed as it went along: as Hockney completed each new shot, he’d place the square on the floor before the seated couple, slowly building up his collage. The two sitters became increasingly absorbed in the process and the portrait turned into a celebration of their intent concentration. Brandt’s soft, intelligent face appears in profile across two squares, leaning further and further forward. His hands seem to start by his shoulder, resting on the high armrest, then slide slowly down the armrest into an almost prayerful clasp just above his knee and then on down his leg to a balancing clutch above the ankle. (Seven hands in all appear, reading as one gesture.) Brandt’s entire posture seems cusped, nestled in the larger arc of his wife’s seated figure. (She, closer to us, likewise gazes down at the developing collage.) “As I was finishing this piece,” Hockney recalled while we examined a reproduction of the collage, “Brandt asked me, ‘Couldn’t you be in the picture, too?’ So I turned the camera back on myself, snapped several shots, replaced the collage at their feet with these shots of my face, and took some more pictures of this new array on the floor. Thus, although they now seem to be looking at a collage of me, what they were actually looking at when I photographed them was the picture of themselves, coming into being.”

FIG 8 David Hockney, Nicholas Wilder Studying Picasso, Los Angeles, 24th March 1982.

As Hockney spoke, I was reminded of a passage from his essay in the National Gallery booklet in which he referred to his own painting of Henry Geldzahler looking at the screen with the reproductions of masterworks by Piero, Vermeer, Van Gogh, and Degas. That painting, Hockney had written, “was about the pleasure of looking. I painted a picture of Henry, who loves pictures, looking at them . . . [so] that you could identify with him and his pleasure, because you were doing exactly the same thing, looking at it.” I mentioned the line to Hockney and he concurred. “Yes,” he said, “I think some of the most effective collages in both the Polaroids and my more recent series involve the theme of looking—of looking at people looking. There’s a kind of doubling, an intensification of the experience. Take this one for instance.” He pulled out the reproduction of a collage of the art dealer Nick Wilder, seated by the pool outside, poring over a volume of Picasso drawings and paintings. “See how Nick has put his hand over the upper half of the picture he is looking at, as we often do when we are looking at paintings, trying to fathom the composition and structure and so forth [Fig. 8]. Well, the Polaroid squares themselves make you look at this picture of Nick in much the same way. The grid guides your eye, summoning up countless varied details and relationships in an almost mathematical profusion. Each middle square is surrounded by eight others, corners are surrounded by three, side squares by five, and so on. Your eye fixes on such groups, then moves beyond them to others. You end up looking at the collage in much the way he is looking at the Picasso reproduction.

“For that matter,” Hockney continued after a pause, “looking itself has been the central subject of all of these collages. Ordinary photography, it seems to me, is obsessed with subject matter, whereas these photographs are not principally about their subjects. Or rather, they aren’t so much about things as they are about the way things catch your eye. I don’t believe I ever thought as much about vision, about how we see, as I have during the last several months.” And Hockney’s collages are in turn a school for vision. Ordinary photographs present a whole, from which details can be elicited. Hockney seems to suggest that this is the opposite of how we actually see the world. For him, vision consists of a continuous accumulation of details perceived across time and synthesized into a large, continuously metamorphosing whole. “Working on these collages,” Hockney explains, “I realized how much thinking goes into seeing—into ordering and reordering the endless sequence of details which our eyes deliver to our mind. Each of these squares assumes a different perspective, a different focal point around which the surroundings recede to background. The general perspective is built up from hundreds of micro-perspectives. Which is to say, memory plays a crucial role in perception. At any given moment, my eyes catch this or that detail—they really can’t keep any wide field in focus all at once—and it’s only my memory of the immediately previous details which allows me to form a continuous image of the world. Otherwise, for instance, turning my head the world would black out at the sides—but it doesn’t! Which is really quite remarkable when you think about it. And which, again, is a part of the visual experience that gets falsified in ordinary photography.”7

One of the most striking things about these Polaroid grids is the way they meld and confound the distinction between the rational and the sensual. The grid bestows an evenness, an equivalence over the entire visual field, and yet within this field a thousand details are endlessly divulging themselves. There is a saturation, almost an oversaturation of pleasure, tempered to a serenity by the democratic matrix of the grid.8

Looking, for Hockney, is interest-ing: it is the continual projection of interest. “These collages only work,” Hockney explains, “because there is something interesting in every single square, something to catch your eye. Helmut Newton, the photographer, was by here the other day, and I said, ‘Everywhere I look is interesting.’ ‘Not me,’ he replied, ‘I bore easily.’ Imagine! I’ve always loved that phrase of Constable’s where he says, ‘I never saw an ugly thing,’ and doing these collages I think I’ve come to better understand what he means: It’s the very process of looking at something that makes it beautiful.”

Hockney paused, suddenly very tired. “Of course,” he said, “thinking intensively about looking forced me to think more carefully about cubism, because looking— perception—was the great theme of cubism. But let’s talk about that tomorrow. I’m afraid I’m getting sleepy. My friends have been amused at my pace these past several months—they say I’ve become like a child, playing for hours on end and then just suddenly conking out. The truth is, I’m not sleeping very well: I keep waking myself up with ideas!”

Driving back up toward Hockney’s the next morning, weaving in and out of the gullies along Mulholland ridge, I noticed the way each new outbound furl of the road would present me with a new view of the same valley—or, rather, the same view only slightly altered, moved over just a bit. I realized that this drive, which Hockney had been taking almost every morning for several years now, must itself have been preparing in him a special “view” of vision.

The door at Hockney’s house was ajar and I entered quietly. Hockney was once again at his worktable, this time leaning down with his face very close to the splay of photoprints in the new combine he was arranging. He nudged one picture over slightly and then slowly stood upright, continuing to look down at the collage, until finally, rubbing his face and breaking the spell, he turned. “Ah,” he said, “hallo,” with that upward lilt in his voice which I was beginning to associate with the onrush of his enthusiasm. “Have you ever noticed,” he continued, as if there hadn’t been the slightest interval since the close of our conversation the night before, “how when you look at things close up, you sometimes shut one eye—that is, you make yourself like a camera. Otherwise, things start to swim; it becomes di‹cult to hold them in visual space. The cubists, you know, didn’t shut their eyes. People complained about Picasso, for instance, how he distorted the human face. I don’t think there are any distortions at all. For instance, those marvelous portraits of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter which he made during the thirties [Fig. 9]; he must have spent hours with her in bed, very close, looking at her face. A face looked at like that does look different from one seen at five or six feet. Strange things begin to happen to the eyes, the cheeks, the nose—wonderful inversions and repetitions. Certain ‘distortions’ appear, but they can’t be distortions because they’re reality. Those paintings are about that kind of intimate seeing.”

FIG 9 Pablo Picasso, The Red Armchair, 1931.

Among Hockney’s Polaroid collages there’s an especially luscious portrait of his friend and frequent model Celia, which seems intended as an homage to these Picasso portraits of Marie-Thérèse (Plate 4). She is wearing a white lacy blouse, one arm thrown languorously behind her head, her cheek resting calmly against the other hand. Her eyes seem to float—there are three of them, two mouths, two noses, and a frond of curls on her forehead that drifts away into the dark surround—a smoky wisp, a whisper of desire.

“Analytic cubism in particular,” Hockney continued, referring to the work Picasso and Braque undertook between 1909 and 1912 (paintings characterized by especially dense visual composition, usually in monochrome grays or browns), “was about perception—about the di‹culty of perception. I’ve recently been reading a lot of books about cubism, and I keep coming upon discussions of intersecting planes and so forth, as if cubism were about the structure of the object. But really, it’s rather about the structure of seeing the object. If there are three noses, this is not because the face has three noses, or the nose has three aspects, but rather because it has been seen three times, and that is what seeing is like. When I showed some of my Polaroid collages in England last year, one critic came up to me and told me that I was completely misinterpreting cubism; I replied, ‘Well, that may be, but if so, it’s only the four hundred and seventy-eighth misinterpretation this year. Only, I don’t think I am misinterpreting cubism, and I’m absolutely certain that it’s cubism today that remains to be dealt with.”9

Hockney’s love of Picasso is of long standing, although only recently has it taken on this sort of urgency. Hockney visited the Museum of Modern Art’s 1980 Picasso extravaganza eight times and subsequently bought the Zervos catalogues, the thirty-two-volume catalogue raisonné of Picasso’s lifework. He even acquired a small Picasso painting (Fig. 10). “I’d originally seen it in Paris,” Hockney recalled that morning, “a lovely rendition of his familiar theme of the artist and his model, seemingly simple but at the same time extraordinarily supple and inventive. A few months later, a dealer offered to trade me that painting for one of my own. I mean, it’s an indication of the present foolishness of the art world that I can be offered a Picasso in exchange for just one of mine. Well, I’m not a collector by nature—postcards will usually do for me (I tack them on the wall)”—Hockney gestured toward the walls about him, which were festooned with dozens of postcards (Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ, Caravaggio’s Last Supper, Toulouse-Lautrec’s Couple in Bed, a Van Gogh self-portrait, Vermeer’s Lute Player, a Cézanne landscape, a Gauguin beach scene)—“but I was thrilled by the offer and I accepted. I keep the painting in my bedroom. I study it. I’m continually discovering new things in it. It must have been made very quickly. I mean, it can’t have more than—well, I’ve counted: it has fifty-two strokes.”

FIG 10 Pablo Picasso, Artist and Model Reclining Nude and Man in Profile, March 29, 1965.

On several occasions recently in Los Angeles, Hockney has delivered a lecture he calls “Major Paintings of the Sixties.” The audiences are invariably surprised when he starts out by proclaiming that the most important art of the sixties did not occur in New York or California or London, nor was it a part of any abstract expressionist, minimalist, or pop movement; rather, it came into existence over a period of ten days in March 1965 in the south of France in an eruption of creativity during which Pablo Picasso created thirty-two variations on the theme of the artist and his model. (One of these is indeed the piece Hockney owns—he discovered the others while researching his own in the Zervos catalogues.) The claim is doubly heretical: other artists are usually considered to have been doing much more interesting work during the sixties, and Picasso himself is thought to have done much more important work earlier in his career. “The sophisticated art world tends to act as if Picasso died about 1955, whereas he lived for almost twenty years after that,” Hockney argues. “Common sense tells you that an artist of that caliber— the only people you can compare him to are Rembrandt, Titian, Goya, Velázquez—does not spend the last twenty years of his life repeating himself. It’s harder to see what he’s doing, perhaps. But he remains to the end far and away the greatest draughtsman of the twentieth century, the artist with the most sensitive and inquiring eye, and the most supple and inventive hand. Those thirty-two paintings are simply richer and more engrossing than anything else that was being done at the time—still, at that age, at eighty-four, Picasso was finding new ways to see, new ways to express his visions!”10

Hockney’s Polaroid collages came into being very much under the thrall of Picasso.11 The portrait of Celia is but one example. Another portrait, of the curator Geldzahler, seated on a rickety stool, legs outspread, cleaning his glasses, echoes Picasso’s 1910 portrait of the dealer Ambroise Vollard. There are allusions to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in other collages, and there are even two still lifes—witty riffs on the old cubist themes of guitar, tobacco can (Half and Half, half in one square and half in the other), wine bottle, and daily journal (in this case, the Los Angeles Times). (When the cubists insisted they were putting time into painting, they’d sometimes show it to you right there, in bold typeface: temps.)

By mid-May 1981, however, Hockney had stopped producing his Polaroid collages. This was partly, perhaps, because the passion had simply spent itself. (He had created over 140 collages in less than three months!) It was partly, no doubt, because he was now needing to redirect his energies from making collages to preparing them for exhibition—the three shows were all on the verge of opening late that spring. But an additional factor was also beginning to make itself felt: Hockney was beginning to sense an interior flaw in the Polaroid medium. Just as cubes are not the point of cubism, squares were not the point of Hockney’s activity. But the square matrix-grid seemed an insurmountable requirement with these collages: one cannot cut the white border from a Polaroid picture the way you might slice off the crust from a piece of bread (with Polaroids, if you slice into the tile, it literally comes apart in your hands; the various layers of chemical pigment come unfixed). While the vision evoked in these grids seemed more true to life than ordinary photography, the white grid itself in a very real sense constricted all that burgeoning life. It wasn’t just that people began focusing on the grid (seeing Hockney’s as yet another in a series of modernist variations on the grid theme—Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, and so forth). Rather, it was that the rectangular grid remained trapped in the aesthetic of the view out a window that had been one of the principal targets of the entire cubist movement.

“It can’t just be a coincidence that cubism arose within a few years of the popularization of photography,” Hockney surmises. “Picasso and Braque saw the flaw in photography—all the sorts of things about time and perception which I’ve only recently begun to appreciate—the flaw in the camera; but in doing so, they also recognized the flaw in photography’s precursor, the camera obscura. Now, the camera obscura was essentially a room—camera means room—it had a hole in it, and the hole was a window. You’re looking out a window, that was the idea. In fact, that’s why you get easel painting, which arose around the same time: the resultant canvas was meant to be a kind of window you could slot into your own wall. This idea of looking out a window dominated the European aesthetic for three hundred years. Interestingly, by the way, Oriental art never knew the camera obscura, and their art instead looks out of doors. The difference between a window and a door is you can walk through a door toward what you are seeing. Much Oriental art takes the form of a screen which, like a door, stands on the floor. You cannot do that with a window: a window implies a wall, something between you and what you’re looking at. A lot’s been written about the influence of Oriental art during the last half of the nineteenth century—Manet’s appropriation of Japanese motifs, Van Gogh’s use of the bold solid colors, Monet’s gleanings of atmospheric perspective, and so forth—but I suspect the Oriental alternative was especially important for the cubists. Because what they were up to, in a word, was breaking that window. Cézanne was getting there: in his still lifes he observed that the closer things are to us, the harder it is for us to place them; they seem to shift. But he still looked through a window at those cardplayers grouped around that café table. Whereas, as has often been said, Picasso and Braque wanted to break that window and shove the café table right up to our waist, to make us part of the game.”

For all the Polaroids had taught Hockney about time and vision, they weren’t going to be able to help him break that window: on the contrary, that quaint white grid made them look even more windowlike than most conventional paintings.

At first, it seemed Hockney had sworn off photography altogether— or, at any rate, had reverted to a decidedly off-again mode. In mid-May he drove north to help supervise the installation of his sets for the San Francisco Opera Association’s production of The Rake’s Progress, by Stravinsky. On the way, he veered briefly into Yosemite Valley, where, using a 35 mm camera, he took one sequence of nine shots of Yosemite Falls—not nine separate shots of the entire waterfall but rather a vertical sequence of nine segmented sections, starting with the sky, trilling down the falls, into the far valley, across a river, up from the near shore, all the way to his own foot, clad in a tennis shoe (Fig. 11). Coming back to the car, he threw the camera into his pack; he wouldn’t develop the film until early in the fall.

During the summer, he traveled to Paris (for the opening of the Pompidou show) and to London (to work in his Pembroke studio), as well as to Martha’s Vineyard and Southampton for a vacation with Henry Geldzahler. He filled three notebooks with drawings, and he started painting again. The principal work of this period (produced at the Pembroke studio) was an eight-panel unfinished painting of four of his friends (the eight panels are divided into four long, narrow bands), clearly a work influenced by his Polaroid excursion: David Graves’s face exists at once frontally and in profile, and he has four arms and three legs; Ian Falconer, on the other side, has two eyes, two noses, two mouths, and three legs. “And yet,” as Hockney pointed out that morning, pushing aside the clutter to reveal the abandoned painting, which he’d brought back with him to Los Angeles, “they don’t read as monsters. They’re clearly and simply individuals in the midst of living. I’ve made something of a leap here: never again will anyone I’m painting have to ‘sit’ for me, in the traditional sense—frozen still for hours. I can deal now with their liveliness.” Late in the summer, Hockney and his friend Gregory Evans traveled by car through the Southwest, to Zion, Bryce, and the Grand Canyon National Parks. He was again taking pictures. They weren’t Polaroids (which are notoriously inadequate for capturing long-distance vistas), although as in the Polaroid collages, he was compiling dozens of details rather than single wide-angle swaths. He wasn’t sure what, if anything, he was up to, and he wouldn’t have an inkling until early in the fall, when, returning to Los Angeles, he had the film developed. Once he’d gotten the prints back, however, he quickly assembled a few collages and realized, with a great new wave of excitement, that he was on the verge of another breakthrough.

FIG 11 David Hockney, First Expedition to Yosemite, May 1982.

These new pieces were different from the Polaroids in many ways. With those Hockney would establish a general perspective but had to move all over the room to compile the details. With the new collages he could stay in one spot, using the camera’s lens to zoom in for details at various distances. (Hockney now alternated between a Nikon 35 mm camera, with its fairly elaborate host of optional lenses, and a much simpler Pentax 110 single-lens reflex camera, which he preferred. Though not much larger than a cigarette pack, it featured a remarkable optical sophistication, and he could slip it into his pocket and carry it around all the time, pulling it out whenever the fancy took him.) The Polaroids took hours to make, but when he’d finished shooting, he’d also finished the collage. With the new pictures, the actual shooting could be completed in a few minutes (as fast as he could reload the camera), but the assembly of the collage occurred only when he got the prints back, days or weeks later, and began building the piece on his worktable in the living room–studio. This second stage of the process could take hours. With the Polaroids, he had had to deal with those white borders, whereas these new photos were printed without borders, hence no white window grid.

“I take dozens of pictures at any given site,” Hockney explains, “and then I just take the exposed rolls down to one of the local places here to have them developed— usually I go to Benny’s Speed Cleaning and One-Hour Processing. It took me a long time to convince them that I truly wanted them to print regardless,’ and I still get these wonderful standardized notices back with my batches of prints, patiently explaining what I am doing wrong, how I should try to center the camera on the subject, focus on the foreground, and so forth. Once I’ve got the prints, I start building the collages, keeping to one strict rule: I never crop the prints. Somehow this seems important to the integrity of the enterprise: the evenness of time seems to be tied up with a regularity in the print size, and things would get all messed up whenever I trimmed the prints. This, in turn, forces me to be aware of how I’m framing the shots as I take them; in effect I end up ‘drawing’ the collages twice.”

Given the dissimilarity of the two processes, it is striking how similar the earliest of these new collages were to their Polaroid antecedents. (For the sake of convenience, I will refer to all the collages in this later series as “photocollages,” as opposed to “the Polaroid collages” of the earlier phase.) They seemed to come as close as one could imagine to the original rectangular grid of the Polaroids: only the white borders were missing. There was little overlap of prints. (Later it would be rare not to find overlaps.) It seemed as if Hockney, given a vista—say, the Grand Canyon, looking north—had simply framed a detail, taken a shot, moved the viewfinder over from the previous detail, refocused, and taken a new one, again and again and then down, zigzagging in rows, back and forth. The resultant collage formed a perfect rectangle and, still, a sort of window. “It’s incredible how deeply imprinted we are with these damn rectangles,” Hockney commented as we looked at one of these early Grand Canyon collages on its cardboard panel. “Everything in our culture seems to reinforce the instinct to see rectangularly—books, streets, buildings, rooms, windows. Sam Francis once told me how odd the American Indian initially found the white settlers: ‘these people who insist on living in rectangular-shaped buildings.’ The Indians, you see, lived in a circular world.

“But these early collages were really more like studies: you did them, just as you do a drawing sometimes, to teach yourself something; it doesn’t matter what they look like when you’re finished, that’s not why they were made. In this case, in retrospect, I realize I was training my visual memory, and this took a lot of time.” Since these prints, unlike the Polaroids, weren’t developing right before his eyes, Hockney had to be aware of which areas he’d already covered and which ones he hadn’t. Even in a rectangular format this exercise required intense concentration. Presently when he’d begin tilting the camera and anticipating intricate overlaps, he would have to hone these skills considerably further.

As soon as he put together the first of these new collages, in September, Hockney realized he was on to something, and within a few days he was on the road again, back to Utah and the Grand Canyon, this time by himself. “I’ve always loved the wide-open spaces of the American West,” Hockney explains. “But I was never able to capture them in photography, to convey the sense of what it’s actually like to be there, facing that expanse—that incredible sense of spaciousness, which is somehow as elusive to ordinary photography as time is. I thought that, among other things, this new kind of photography might be able to capture that sense of vast extent.”

Hockney took thousands of pictures during the next three or four days, enough, in fact, to compose twenty-five collages (although it would take over a month to assemble them once he got home). A few of them were intimate: one collage in particular wittily celebrated the possibilities of the new medium by affording an otherwise impossible continuous rendition of the view from the driver’s seat in Hockney’s car. But most of the collages from this trip concerned wider vistas, portrayed with astonishing clarity. Ordinarily, the photographer of such a vista has to choose one point of focus, with the result that things closer or farther or to the sides are progressively more out of focus—this, according to Hockney, is another way in which photography falsifies the experience of looking. “Everything we look at is in focus as we look at it,” he explains. “Now, the actual size of the zone the eye can hold in focus at any given moment is relatively small in relation to the wider visual field, but the eye is always moving through that field and the focal point of view, though moving, is always clear.” The experience of this kind of looking is preserved in the collages, where each frame of distant butte or nearby outcropping is in focus and comprises just about as much of the field as the eye itself could hold in focus at any one moment in the real world.

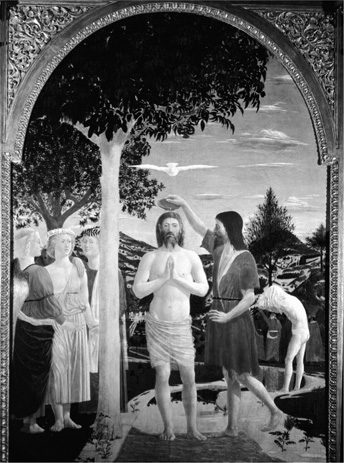

The pictorial rigor and clarity of these panels recalls the treatment of space in paintings by Van Eyck, say, or Piero della Francesca, two of Hockney’s favorites (Figs. 12 and 13). These artists, too, went to great lengths to record each “object” at its moment of clearest focus—every object on the canvas, “near” or “far,” can bear the weight of focused attention, just like the real world, and precisely unlike the world as portrayed in conventional photography. “I’ve always loved the depiction of space in early Renaissance pictures,” Hockney explains. “It’s so clear. I think that clarity is something that has to exist in all good pictures. The definition of a bad picture for me is that it’s woolly—those paintings aren’t ever, no matter what’s portrayed. If it’s a mist, it’s a clear mist and not a woolly mist. There has to be this clarity, which is the clarity of the artist who did it, the clarity of his vision, his sense of being.”

FIG 12 Jan van Eyck, The Annunciation, ca 1434/1436.

FIG 13 Piero della Francesca,The Baptism of Christ, ca 1450.

The major breakthrough in these new photocollages had less to do with the early Renaissance, however, than with high cubism. For the first time, on this second trip to the Southwest, Hockney was beginning to break the window. Looking at that set of collages from his first trip, Hockney had quickly realized what was wrong: there was an arbitrariness to the edge, particularly the bottom edge. To a great extent, conventional photography is about edges, about how to frame the object of vision. Indeed, that is the ordinary photographer’s main contribution to the moment of seeing, his sense of composition, how he chooses to frame the world within four perpendicular edges. “But I wasn’t interested in that,” Hockney insists. “Already with the Polaroids, that sort of composition wasn’t an issue: I could have added a strip of squares to the left or the right, or removed one, without really affecting the experience of seeing those collages. The cubists had a lot of problems with their edges—sometimes they tried to solve these by creating circular paintings—and it’s easy to see why: there are no edges to vision, and certainly no rectangular edges.” For Hockney, to stop at some arbitrary middle distance was completely alien to the kind of vision he was now attempting. Looking at those first collages of the Grand Canyon, he immediately realized that he had to bring the picture right up to the viewer, that he had to bring the distance right up to his own feet and include the ground right in front of him, as well as the canyon beyond.

“Cubism, I realized during those few days,” Hockney continued, “is about our own bodily presence in the world. It’s about the world, yes, but ultimately about where we are in it, how we are in it. It’s about the kind of perception a human being can have in the midst of living.” A few months after this conversation, Vanity Fair highlighted some of these collages in its May 1983 issue, suggesting that they somehow blended “NASA spaceship photography with cubism.” And there was a certain striking similarity: just as the telescopic photographs of distant nebulae that were popularly reproduced around the time Jackson Pollock produced his lush optical fields might be seen as having influenced them, so Hockney’s work can be seen as having come into existence under the sign of NASA—the sequential shutter-streams of overlapping photographs recording lunar and Martian landscapes, for example, or Saturnine rings. But it’s precisely the connection with cubism that upends this false analogy: Hockney’s collages, like cubism, are a record of human looking. It is exactly the point that an automatic machine could not possibly have generated them.

From this point on, Hockney usually included photos of his own feet in these collages. In effect, they stood in for him; they planted him as they plant any subsequent viewer. Indeed, standing there, facing forward into the world before them, the world of vision, these feet seem transposed figures for the eyes themselves. Several of the Grand Canyon collages are huge and spectacular, long banners of looking made up of hundreds of prints. The horizon line curves, but not as in the artificial distortion caused by wide-angle lenses; rather, the gentle swell seems to suggest the curvature of the earth; even more to the point, it replicates the actual movement involved in looking at a long horizon line, how, as Hockney points out, “your head starts out low, looking far to the side, then rises slowly on the neck joint as it moves toward that part of the horizon directly before you, falling again as it moves on to the other side.” Sometimes in these collages there is an almost vertiginous sense of depth. In one, for example, the horizon line stretches across the very top row of photos; as the viewer’s eyes descend the collage, they descend into the canyon (the falling flanks of several buttes guide one’s viewing): only, as one’s eyes descend still further, to the bottom of the collage, they quickly ascend back up the nearer rim to the foreground, which is as high as the horizon at the top. At the heart of this collage, perception itself seems to bend, much as it seems to when one is actually standing at the canyon ledge.

FIG 14 David Hockney, Merced River, Yosemite Valley, California, Sept. 1982.

FIG 15 David Hockney, Merced River, Yosemite Valley, Sept 1982.

But Hockney took one of the most noteworthy of the collages from this period along the Merced River in Yosemite Valley, which he visited on his return drive, somehow managing in them to convey how the sound of a rushing stream looks (Fig. 14). The rectangular grid of the earliest photocollages seems to shake apart before our very eyes amid the surging onrush of the cold tumbling mountain water. “I’m not sure in which of these collages I actually moved beyond the gridlike placement of the prints,” Hockney explained as we looked at this panel that afternoon in his studio. “I was doing several of them at once. But with this one, after I’d assembled the collage in this new jumbled sort of format, I went back and took another set of the same prints and reassembled them in the stricter perpendicular grid of the earlier photocollages. You can see the difference.” He pulled out a panel with the second version (Fig. 15) and set the two side by side. The one in the grid format flattens space to equivalence and stillness; the jumbled version, with its angles and overlaps, allows for a greater sense of depth (the stream receding into the distance) and movement (the stream cascading into the foreground), giving the viewing experience a topography of highs and lows, of concentration and release.

The photos which were to compose perhaps the finest of all of these early photo- collages were taken not on the road but rather just down the road. One afternoon back home in the midst of a long siege of composition and collation, Hockney took a break and went out for a walk, the little Pentax, as usual, in his pocket. He came upon a telephone pole. This was along a stretch of canyon road where the houses are cantilevered over a precipitously falling slope (driveways seem to leap off the roadway into levitating garages). There were houses on either side with, between them in the distance, a beautiful view of the valley and, between them in the foreground at street level, this looming wooden telephone pole. Just in front of the telephone pole were two metal mailboxes on posts. Charmed, Hockney began snapping. The collage he put together a few days later (Plate 6) constituted his most radical break yet with the window-rectangle aesthetic. One sequence of prints scales the telephone pole to the top; another follows the cement steps as they wend down the sides of the houses, so that your eye has no sooner descended the towering pole than it’s sliding right down the mountain face. Hockney’s compositional delight is almost palpable: “There,” he seems to be taunting conventional photographers, “top that!” The rendering of the mailbox closest to the viewer is extraordinary: through the subtlest of juxtapositions and edge-notchings, Hockney lets us sense the space immediately behind the mailbox, how it gives out onto the view of the valley—while at the front of the mailbox, the latch seems to jut right out into our hand: we can barely keep ourselves from reaching out with our index finger and popping the door open. The entire collage, meanwhile, constitutes a playful homage to the cubist guitar, the pole reading as the guitar’s long neck, the cables as its taut strings, the lineman’s rungs as its measured frets, the wrought-iron curlicues on the mailbox post as the design work on the instrument’s front panel, and the arched mailbox door in the middle of the collage as its sounding hole.

Hockney spent much of the fall of 1982 and the winter of 1983 traveling. Early October found him still in California, but by November he’d journeyed to England, where he visited with his mother in his childhood hometown of Bradford, in Yorkshire. On the way back, later in the month, he stopped in New York City to assist John Dexter and the Metropolitan Opera in their restaging of Parade. By mid-December he’d returned to California, where his mother joined him for Christmas. In January, he traveled to Minneapolis, where he worked with Martin Friedman of the Walker Art Center on an upcoming exhibition of his stage designs, and then he was off again to London. Early in February he was back in Los Angeles, but by the end of the month he’d left for Japan to participate as a panelist at a paper conference. Everywhere he went he snapped pictures, and whenever he was back in Los Angeles he’d assemble the harvest into collages in his living room. It was an extraordinarily productive period: even with all the interrupting travel, between September 1982 and March 1983 Hockney managed to complete almost two hundred photocollages.

As with the Polaroid series, landscapes soon gave way to his truer passion: people. Many of these middle-period photocollages (those taken between mid-October and Christmas) are noteworthy. A series of figure studies in the pool, taken in early October, revel in the possibilities of the new medium: for starters, Hockney this time is in the pool, along with his subjects. The collages of people floating languidly are built up from shots taken both above and below the waterline—it takes the viewer a moment to realize how improbable a feat this would be for most ordinary cameras or, for that matter, the unassisted eye. By focusing in a little tighter for the underwater shots, Hockney renders the body below the waterline somewhat larger, more buoyant, than the head above: what is depicted here is the feeling of floating.

Another theme carried over from the Polaroid series is that of looking at people looking. When David Graves sits looking out a window onto a wet London street, every shot, indoors and out, is in focus, except for those describing Graves’s head, which blur in sympathy with the outwardness of his looking—his even concentration seems to encompass everything except his own activity of concentrating. We say, “He is lost to himself.”

Hockney’s mother is the subject of several of these collages as well. In one, taken during his November trip to England, Hockney portrays her in a blue-green raincoat on a slate gray afternoon in the cemetery outside Bolton Abbey, in Yorkshire (Plate 7). The grass in the foreground is wet and marvelously described—a rich pelt of individual green blades. In the background rise ancient gravestones: his mother sits leaning against one of them. There is a blank rectangle, a lacuna in the middle of the collage immediately above her head—an empty plot, her consciousness perhaps of her own mortality? It is at any rate a portrait brimming with remembrance: Bolton Abbey, Hockney explains, is one of the places his late father and his mother used to go sixty years ago, when they were courting.

These and the countless other photocollages of this middle period constitute an exploration of how people are couched in space and how that space is couched in time, the time of looking. The viewer, looking, experiences a living relationship, in time, and yet it’s a strangely unreciprocated one: the people in the picture, suspended, don’t quite live back at us. It was this fixity that Hockney, by mid-December, would be seeking to shatter.

A poster commission for the 1984 Winter Olympics proved the occasion for one of Hockney’s first efforts in the new direction. “I decided to do a study of an ice skater,” Hockney recalls, “and I invited a skater friend to join me at a rink in New York City. I watched him for some time, and I noticed something very odd: you never see the blur. The convention of the blur comes from photography; it’s what happens when motion is compressed onto a chemical plate. We’ve seen so many photos of blurs that we now think we actually see them in the world. But look sometime: you don’t. At every instant the rapidly spinning skater is distinct. And I wanted somehow to convey this combination of speed and clarity.” The resultant collage has a lot of spin—legs flying, skates scraping, shirt billowing, head turning, arms rising, everything converging on and moving out from the focused center, the waist—but no blur.

A series of studies Hockney undertook a few days later, back in his Los Angeles home, during a particularly gemütlich dinner with his friends Billy and Audrey Wilder, proved both simpler and more successful. At one point, following dessert, Hockney noticed that Billy Wilder was fixing to light his cigar, and he immediately reached for his Pentax. In the resultant collage (Plate 8), a flourish consisting of merely six overlapping prints (and the bottom one, with only the two beautifully described wineglasses on the table in the foreground, doesn’t really count), Hockney shows Wilder striking his match, bringing it up to his face, inhaling, momentarily distracted from the conversation, which he already seems bent on rejoining; the last print finds him looking up, pu‹ng contentedly, obviously framing some repartee. (I say that the bottom one doesn’t really count, but then look again, for those two wineglasses both establish a sense of conviviality and Hockney’s own presence at the table and give a wider sense of spaciousness, grounding the whole scene. Block out that print with your hand and you will see all that gets lost.) The prints fold one on top of another: the entire piece reads as one carefree, casual gesture—a toss-off.12

On the first day of the new year, Hockney, his mother, and his friend Ann Upton sat down at the wooden table in his living room to play a game of Scrabble, with David Graves keeping score (Plate 9). “The game lasted two hours. I was clicking away the whole time,” Hockney boasts, “and I still came in second! Naturally, my mother won.” And looking at the picture, you can see she’s going to: her face appears a half dozen times, in different degrees of close-up, and every shot captures the visage of a shrewd, veteran contender. boss hen reads the bottom file of words as the board faces Hockney. (The words scowls, sobs, and pool are also floating in there.) The plastic board is mounted on ball bearings so that it can be rotated from one player to the next. Hockney has taken his details of the board at various moments of the game and cleverly interwoven them in the center of the collage so that it’s possible, with a little study, for the viewer to reconstruct the entire game, or at least its key moments. We watch as Mrs. Hockney concentrates and then scores a handsome windfall by centering vex over a double-word square—a neat twenty-six points. The board presently comes around to Ann, affording her access to a triple-word corner slot—she ponders and ponders (five separate faces) and finally ventures the truly pathetic net (three lower-scoring letters could not have been found). David Graves, keeping score, looks over her shoulder, considers her predicament, and then breaks into a grin at her solution: three times one times three—nine points. A cat on the side of the table looks up, rummages around, and falls back to sleep. Hockney’s own tiles are arrayed on their stand before him: lquireu. “He was trying for ‘liquor,’” one cognoscente hypothesized at the opening in New York, the day this collage was first exhibited, “only he kept his ‘Q’ way too long into the game. You can’t just hold onto those big letters, endlessly waiting for the right vowels to come along.” “I don’t know about that,” replied her friend. “What about ‘liqueur’—that would have given him a fifty-point bonus for using all his letters, if he could have attached it to an ‘S.’” And the extraordinary thing about this collage is that it lends itself to that kind of second-guessing—it opens out onto that kind of storytelling. Indeed, it simultaneously tells a story and presents a group portrait. Dozens of hands, eyes, faces, a spinning board at countless angles: and yet at all times a recognizable picture of a group of three (implicitly four) individuals engaged in an immediately recognizable activity.

FIG 16 David Hockney, Sitting in the Zen Garden at the Ry anji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 19, 1983.

anji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 19, 1983.

FIG 17 David Hockney, Walking in the Zen Garden at the Ry anji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983.

anji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983.

These increasingly sophisticated collages built toward the series Hockney undertook on his February trip to Japan. Indeed, the Japanese collages offer perhaps the finest elaboration of many of the themes we have been considering thus far.

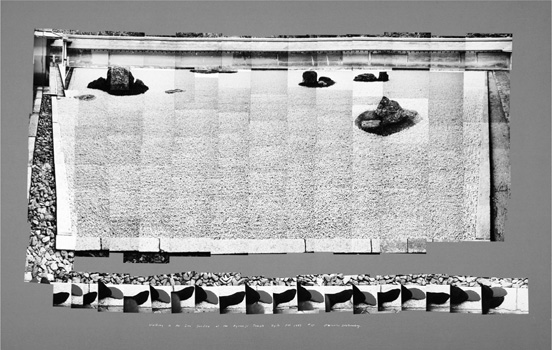

The rock garden at the Ry anji Temple in Kyoto, for example, the subject of several drawings by Hockney during earlier trips to Japan, became on this trip the site for further research into the dissolution of the rectangle. “What I began to realize in putting some of these recent ones together,” Hockney explained as we looked at the first of two studies of the Ry

anji Temple in Kyoto, for example, the subject of several drawings by Hockney during earlier trips to Japan, became on this trip the site for further research into the dissolution of the rectangle. “What I began to realize in putting some of these recent ones together,” Hockney explained as we looked at the first of two studies of the Ry anji rock garden, “is that it’s the solid, no matter what shape, that constitutes the rectangle and constrains like the rectangle. You have to open it up, put holes in the middle, and stretch bands off to the side to get away from the window aesthetic.” In the first Ry

anji rock garden, “is that it’s the solid, no matter what shape, that constitutes the rectangle and constrains like the rectangle. You have to open it up, put holes in the middle, and stretch bands off to the side to get away from the window aesthetic.” In the first Ry anji collage (Fig. 16), Hockney sits on a wooden step, looking out from a corner of the Zen garden. The garden itself is a large outdoor rectangular field, covered with meticulously raked white pebbles and punctuated by occasionally obtruding half-buried boulders. The dimensions, the spacing of the boulders, the pattern of the raking—everything has been exquisitely calibrated to encourage calm meditation and spiritual renewal. (The rocks rise like islands in the sea of pebbles, the mossy patches spread like miniature forests over the rocks.) Hockney’s collage includes the wooden eave floating disembodied above him, receding into the distance where it eventually joins the back wall, and below the eave, the deck with people sitting and standing, looking out, watching. The Zen garden branches out in a seeming V from the corner where Hockney sits. A narrow band of black tile pavement between the wood deck and the white curbstones skirts the gravel field, further emphasizing the way space recedes along both sides of the V. A low yellow wall bounds the rectangular field on the far sides. In the middle of the collage is an irregularly shaped blank that exists partly, Hockney explains, because he was interrupted as he was taking his pictures and simply failed to record these middle frames. But the hole also works to further sabotage the window illusion, reading (like the boulders in the field of white gravel) as a zone of nothingness, of serene nullity in the heart of being.