For a long time his cameras had been getting smaller and smaller. Polaroid. Nikon. Pentax. A little tiny pocket job, James Bond style. “More and more lifelike,” is the way David Hockney had put it to me a few years back when he had been describing his ongoing explorations and I was preparing the introductory essay for the Cameraworks volume, which was going to document some of those investigations. “More true to life. I mean, one’s own eye doesn’t hang out of one’s face, monocular, drooping at the end of some long tube. No, it’s nestled in its socket, rolling about, free and responsive. And I feel a camera should be as much like that as possible.”

Deploying his increasingly tiny cameras, he’d been generating increasingly mammoth collages: dozens, hundreds, presently thousands of snapshots shingled one upon another, resolving into ever more intricate and lovely portraits and vistas. An explosion of perspectives—and in the process the utter subversion of the tyrannical hegemony of traditional one-point perspective.

“Wider perspectives are needed now,” Hockney would proclaim as he pulled a camera the size of a cigarette pack out of his pocket and started up once again, snapping away.

So you can perhaps imagine my surprise recently, when Hockney invited me out to his home and studio in the Hollywood Hills above Los Angeles to have a look at some of his current work, at finding him hunched over his latest camera: a full-ton monster—a huge blinking box—a Kodak Ektaprint 222 office copying machine. Hockney looked up for a moment, beckoned me in, and returned to his labors: snapping, as ever, away.

Hockney’s studio is built up over the former tennis court above his amphitheatric home, and the copying machines (for there were two, a Canon NP 3525 as well) actually occupied only half the court. The other half was taken up with a large three-dimensional model of his stage designs for an upcoming production of Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Indeed Hockney’s workday that month seemed to consist in a regular volleying, as it were, between Wagner and Xerox. That particular afternoon, however, he mainly seemed interested in talking about his explorations into the artistic possibilities of copying machines.

“A while back,” he told me, “as you may remember, I used to enjoy confounding people by declaring that the only thing a photograph might be able to convey with some degree of truthfulness would be a flat surface, as in the reproduction, say, of a painting. When it attempted to depict space, that’s when photography seemed to me to get into trouble. The camera, although people think it sees everything in front of it, cannot see the main thing we get excited about in front of us, which is space. The camera cannot see it. Only human beings maybe, or anyway only living beings, can see space. That’s part of what I was exploring with all those photocollages: how a camera might be transformed to convey space after all, which means how it might be forced to acknowledge time. But it’s only just now that I’ve been returning to my initial insight, which is how good a camera is at conveying a flat surface and the possibilities which that particular sort of effectiveness might afford.

“Because an o‹ce copier is a camera,” Hockney continued, patting his giant beast of a colleague. “When you use it to copy a letter, you’re basically getting a photographic reproduction of the letter. It’s a camera, and it’s also a machine for printing. Over the years, I’ve made a lot of prints working in several different master printshops. It’s an exciting process, but I’ve always been bothered by the lack of spontaneity: how it takes hours and hours, working alongside several master craftsmen, to generate an image. How you’re continually having to interrupt the process of creation from one moment to the next for technical reasons. But with these copying machines, I can work by myself—indeed you virtually have to work by yourself; there’s nothing for anyone else to do—and I can work with great speed and responsiveness. In fact, this is the closest I’ve ever come in printing to what it’s like to paint: I can put something down, evaluate it, alter it, revise it, reexamine it, all in a matter of seconds. Actually I’ve been trying to come up with a name for what to call these things”—he gestured toward a wall where several of his photocopied creations were hanging on display—“and I’ve hit on the phrase ‘Home Made Prints.’”

To understand how Hockney was generating these Home Made Prints of his, it’s useful to keep in mind the model of a self-contained print studio. The prints are wonderfully colorful and various; yet within each edition they are consistent from one “pressing” to the next. But Hockney was not simply producing a finished image, hundreds of color copies of which he was then proceeding to mass-produce out of his copying machine. Rather he was working in layers, as in a standard print workshop. Much of his activity over the past several months, he now informed me, had consisted in exploring what things look like when they’re photocopied, how the machine sees them; and to find out, he’d been photocopying everything in sight: leaves, maps, grass, towels, shirts, Plasticine models, painted images, gouaches, washes, ink-thatches. He’d explored how the machine reads these various subjects at various settings and in various colors. He’d even been in touch with some of the technicians at Canon in Japan, having them brew him up some new colors, specifically a yellow for which no previous customer had ever seemed to have any call.

He photocopied everything, and then he cut and collaged. The prints he was eventually creating were thus the culmination of several dozen different operations. By the time he was ready to make an edition of any specific print—say, the charming portrait of his new intimate companion, a dachshund puppy named Stanley, which he was “editioning” the afternoon I came to visit (Plate 25)—he might have six or ten or fifteen different sheets of paper, layers of the image, which he would now begin successively “combining” inside the photocopier. He’d load the machine’s paper feed bin with high-quality Arches paper, the sort used by the finest print studios, lay his first image on the glass screen, select a color and a setting, run a few copies, recalibrate the settings, and then shoot a hundred sheets, say, through the machine. He’d then take those hundred sheets, evaluate their consistency, reject any copies that failed to pass muster for one reason or another, and then put the remaining sheets back in the feed bin, replacing the first image on the screen with a second and repeating the process. (In this particular instance, a soft light brown wash was being superimposed on the witty, crisp black-ink outline of the first pressing— or rather Hockney now replaced the machine’s black pigment with brown from one of several canisters he kept alongside the copier; the actual image on the sheet Hockney was photocopying was the palest gray watercolor. Hockney explained that the machine seemed to read the white-gray contrast better than it would a white-brown.) By the end of this particular run, only thirty sheets survived all the operations, and they came to constitute the complete edition of that particular print. Everything else was fed into a nearby paper shredder, which digested the debris into exceptionally high-quality confetti.

It was not only the spontaneity of the process that Hockney seemed to be enjoying in his newly discovered medium. There were certain ancillary benefits he’d come upon along the way as well—for one thing, the blacks. “I’ve never been able to generate such blacks before,” he declared, pointing to the incredibly luscious black tree trunk, set off by a simple, almost luminous green leaf in one of the prints tacked to the wall. “I think it has something to do with the process by which the pigment is made to adhere to the page. In almost every other printing or painting process the pigment is conveyed to the page through a liquid medium of some sort, which then both evaporates into the atmosphere and is absorbed into the page, in either case leaving a sort of visual residue. No matter how black, there’s always a trace of reflectivity, a sheen, and you don’t get that pure sense of void. With photocopying, however, the powdered pigment is conveyed onto the page by a heat flash rather than a liquid. And there’s therefore no subsequent reflective sheen. Just this rich, wonderful black.”

Most of these prints seemed to have an uncanny presence and clarity, a startling immediacy. “Somebody the other day was telling me how one of these images just seemed to pop off the page for him,” Hockney commented. “But I think that that formulation is subtly wrong. In most other printing processes there are several intervening, intermediary stages in the production, and in a way you can see them in the finished product. The image seems to be hanging back, to be subsumed, as it were, a few millimeters beneath or behind or below the surface of the sheet of paper. But here the process has been more direct—no negatives, no apparatus, just paper to paper—so that if anything, the image can be said to have popped onto the surface of the page.

“In general,” Hockney continued, “it seems to me that most reproduction in the past has tried to behave as if the page were not there, as if you were looking through the page to the image which was just beyond it, as if the page were like a pane of glass. I’m reminded of those extraordinary George Herbert lines, which have fascinated me for years:

A man may look on glass,

On it may stay his eye;

Or if he pleaseth through it pass

And there the Heaven espy.

But what I’ve been trying to get in some of these recent prints is the beauty of the surface itself, of color on paper, the Heaven that’s there. Heaven isn’t far away; it’s right there on the surfaces before us.”

In other words, it was a typical visit to Hockney’s studio: the still young, not-that-young artist utterly engrossed in and possessed by some new passion, relentlessly pursuing it through all its myriad permutations. Hockney is an awesome worker: the sheer amount of his production—its variety and the density within that variety—is staggering. And all the more so because that sheer intensity of labor runs so contrary to his public persona as a ubiquitous presence in society, an endlessly vacationing, lotus-languid bon vivant. Few artists, with the possible exception of Andy Warhol (for whom such exposure was itself, in a sense, near the core of his artistic vocation), have so often found their countenances gracing the pages of fashion magazines and artsy journals. It’s David Hockney here and David Hockney there. Indeed in this regard Hockney sometimes reminds me of Kierkegaard or at any rate of the perhaps apocryphal stories about Kierkegaard, who, it was said, used to disguise his own ferocious productivity—particularly during the 1840s, when he was penning a whole series of volumes under countless pseudonyms (each “author” seeming to attack all the others)—by continually traipsing about Copenhagen behaving like the most flamboyant and unregenerate of dandies. He’d make a particular point, or so the stories went, of showing up each evening at the opera, making a grand entrance into the concert hall, sitting through the overture, and then ever so quietly, without provoking the slightest notice, exiting the hall and hurrying back to his desk and his countless pseudonymous tasks. (Indeed the exercise was essential to the success of the whole pseudonymous venture; everyone was avidly wondering who all these wildly contentious new authors were, but nobody ever so much as suspected that idle dabbler Søren Kierkegaard.)

I mentioned that story to Hockney now, as I gingerly moved him away from the force field of his photocopying machines and over to a set of easy chairs in the studio’s midcourt, and he started to laugh before I could even complete the analogy. “Ah, yes,” he said, “I see what you’re getting at. I mean, I don’t really care what people think, but it is funny. A few months ago, for instance, in New York, a friend of mine urged me to come along to the Palladium. I didn’t want to, I don’t like discos, and I can’t stand the music, but in the end I went as a sort of favor to her. And sure enough, there were all these people there photographing other people, and they all photographed me, so that even though I only stayed for about half an hour, the photos were appearing for weeks thereafter. I can see how it could give someone the impression that I’m out partying every night, even though, in fact, I hardly ever go out. But I don’t care. In fact, there are certain advantages to people’s not taking you too seriously.”

Like what?

“Well, think of it the other way. If you’re taken very, very seriously, you run the risk of becoming bogged down in another direction, which I wouldn’t like. One’s freer this way. I mean, I take my work seriously, I don’t take myself too seriously, but if you spend your whole life doing it, you’re obviously taking it seriously in a way. You don’t choose to do all that work as a mere dalliance, as nothing at all.”

He went on to point out how, for instance, some people, observing his photo albums, imagine he’s on vacation all the time. “The thing is,” he said, “that’s what makes those albums utterly ordinary. Everybody’s photo albums document them with their friends and when they go on holiday. People don’t spend much time photographing the street they live on. Although, actually, my backyard has been the subject of most of my work. People see me as some sort of hedonist because I always seem to be portraying either my California home or my various travels. But I never traveled out of boredom or the need for new impressions. I’ve always realized that the bored person will be bored anywhere. The reason I moved from one place to another was to find peace actually, peace to work. It was the nattering that usually got me down. I fled for peace and quiet in each case.” It occurred to me, as Hockney said this, that the reason we think he’s always on holiday—in Mexico or Provence or China or Japan or the Southwest and so forth—is because of all the work he brings back from these travels. He portrays others lounging about sleepily—sometimes in his drawings it seems that all the world’s a nap—but he’s wide awake and deep at work.

“That’s why I settled here in California in 1979, for that matter,” he continued. “It suits me here. You can live more privately here than anywhere else and yet still be in a city. In a way I moved here for the isolation.”

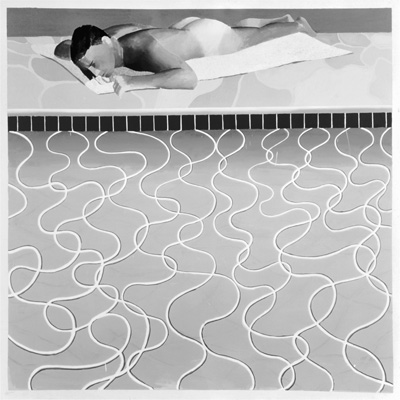

It’s not just the locales portrayed that often give people the wrong impression about Hockney’s intentions. “I mean,” he continued, “it’s like people say, ‘Ah yes, you paint swimming pools.’ But I must admit, I never thought the swimming pool pictures were at all about mere hedonist pleasure [Fig. 20]. They were about the surface of the water, the very thin film, the shimmering two-dimensionality. What is it you’re seeing? For example, I once emptied out my pool and painted blue lines on the bottom. Well, now, when the water’s still, you see just clear through it and the lines are clean and steady. When somebody’s been swimming, the lines are set to moving. But where are they moving? If you go underneath the surface, no matter how turbulent the water, the lines are again steady. They are only wriggling on the surface, this thinnest film. Well, it’s that surface that fascinates me; and that’s what those paintings are about really.”

The same as with the Xeroxes.

Spend any amount of time with Hockney and you quickly realize that he’s an intensely cerebral artist, extraordinarily well read and deeply involved in that reading and extraordinarily thoughtful in those terms about the wider implications of his artistic endeavor. He is endlessly struggling with issues of representation, perception, reality, worldview, the transcendence of constrictions. Curiously, however, most of those implications pass most of the fans of his art right by. What makes Hockney such an iconic presence in contemporary popular culture, it seems to me— all the Hockney posters on living room walls, the Hockney reproductions on the jackets of novels and the covers of records, and so forth—is the sunny benevolence of the subject matter and the unfailingly endearing charm of its rendering. I asked Hockney whether he ever became bothered by the misreading—or anyway, the half-reading—of his work. “I suppose even in the experimental work I have to do it in a charming way,” he replied. “That’s just my personality. I can’t not do it that way, you see. When people say, ‘Ah, but it’s much too charming,’ I don’t really care, because I know something else is going on as well.”

FIG 20 David Hockney, Sunbather, 1966.

I asked him about the roots of that charm. “I think ultimately what it is, is that I’m not a person who despairs. I think that ultimately we do have goodness, really, in us. For instance, with the Ravel opera [L’Enfant et les sortilèges, for which he did the stage designs in 1980], I totally responded to that story and the music particularly. And what was it saying? That kindness is our only hope. I think that was in every note of that music. Stunning. And I loved it. I did what I could to make it alive in the theater because basically I believe that. And if I do believe that, that’s what I should express. That’s where my duty lies. I mean, I’m not naive. I have moments—I don’t think happiness is . . . We just get glimpses, tiny moments, that’s all. But they’re enough. At times I feel incredibly lonely, especially when I’m not working. The impulse can go away, just dry up. But the moment I get to work, the loneliness vanishes. I love it in here, on my own, painting. You know all that stuff about angst in art: I always think Van Gogh’s pictures are full of happiness. They are. And yet you know he wasn’t happy. Although he must have had moments to be able to paint like that. The idea that he was a miserable wretch and mad is not true. When he was mad, he couldn’t paint, actually.

“I guess basically I’m an optimistic person,” he continued. “I ultimately think we will move on to a higher awareness, that part of that road is our perceptions of the world as they change, and I see art as having an important role in that change.”

A somewhat subtler misperception about Hockney’s art is that he is essentially a painter and that all the rest—the theater work, the photocollages, the lithographs, the paper-pulp pools, the Home Made Prints—are somehow secondary, incidental, or tangential, a series of holding actions or at best experiments leading back to the more serious work of painting. Various commentators have expressed exasperation over Hockney’s propensity for such side trips, and they’ve wondered when he was going to return to the more essential labor. Occasionally Hockney himself has reinforced that sense of priority. “Oh, dear,” as he’d said to me the day of the New York opening of his photocollage show back in 1983, when we’d walked from the gallery over to the Museum of Modern Art and were suddenly delivered before Cézanne, Braque, and Picasso. “Oh, dear, I truly must get back to painting.” More than three years had now passed, and although he had, in fact, produced a few new paintings—including the major two-panel rendition of A Visit with Christopher and Don (1984; see Plate 12)—he seemed to be as consumed as ever with his experiments in photography, printing, theater design, magazine layout, and so forth. I asked him whether that hierarchy of expectations mattered in any way to him.

“Less and less,” he replied, “if at all. I mean, they’re all tending toward the same set of issues—the clear depiction of space in time, the widening of perspective, and so forth—just in different media is all. And they all influence each other. Dis- coveries in one area move the other along. Just today I made a breakthrough with the design for Tristan based on some of the negative-positive contrasts I’ve been able to generate with the photocopying machines. Both the Xeroxes and the photocollages have been moving more and more to the condition of painting—you can see that especially with that recent Pearblossom Highway collage [1986, Plate 11], which is the most painterly of any of those I’ve done. At one point somebody did criticize the photographs for being less like art than the others, and I must admit I couldn’t care less in a sense whether they are art or not. I mean, it’s not up to me to say, and maybe it’s not up to him either. It’s certainly interesting where they’re leading and where they’ve led, and you don’t stop in the middle of it all because, you know, ‘Gee, I’m not sure if this is art anymore.’ There’s a wonderful quote of Picasso’s, which I keep referring to, where he says he never made a painting as a work of art; it was always research and it was always about time. On another occasion somebody was giving him a hard time about something—I forget what the argument was, but Picasso’s reply was, ‘Ah, then what you’re talking about is mere painting.’ Meaning, of course, that it’s always about something else, something bigger. All of this work is undertaken in a spirit of research. I’m not so much interested in the mere objects I’m creating as in where they’re taking me, and all the work in all the different media is part of that inquiry and part of that search.”

Such probably would not have been his answer to that question back in the early seventies, when painting was still clearly central to his prodigious production. Ironically though, it was a sort of crisis in the paintings of that period—a sense of deadendedness that persisted through much of the rest of that decade—which launched him into the other media. The blockage with those paintings provoked questions— at first barely articulated—which provided the contours for much of the research that was to follow

“Actually it was only a relatively short period,” Hockney recalls, “from 1969 to 1972 or so, where I did a number of paintings in a naturalistic style with a very clear one-point perspective. In fact, it was so clear that the vanishing point was bang in the middle of the canvas. In the 1969 portrait of Henry Geldzahler [Fig. 21] there’s an absolute vanishing point for everything there just slightly above his head. What I wanted to do, what I was struggling to do, was to make a very clear space, a space you felt clear in. That is what deeply attracts me to Piero, why he interests me so much more than Caravaggio: this clarity in his space that seems so real. Well, I just couldn’t achieve that clarity, frankly; it was a hopeless struggle, and the painting I eventually gave up on was the double portrait of George Lawson and Wayne Sleep (1972-75), which I never exhibited, though it has been reproduced; it’s a very dull picture.”

FIG 21 David Hockney, Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott, 1969.

It was reproduced in the 1977 volume David Hockney by David Hockney, where, interestingly, Hockney gives a different account of his reasons for abandoning the picture, as he understood them at the time, citing his growing dissatisfaction with acrylic versus oil paints and a growing disillusionment with “naturalism.” Henry Geldzahler in his introduction to the volume, speculates—no doubt basing his speculations partly on contemporaneous conversations with Hockney himself—that “in the early 1970s Hockney’s technical facility grew to such a degree that it frightened him into pulling back.... The double portrait George Lawson and Wayne Sleep, abandoned in 1973 and resumed in late 1975, achieved such heights of naturalism and finish that a sentimental and anecdotal quality in the subject matter threatened to undermine the painting’s formal strengths.”

Ever since his remarkable debut as an artist in the late fifties Hockney’s work had been characterized by a youthful zest, a fresh sense of freedom, a playfulness. I started to make this point, but Hockney interrupted me. “If art isn’t playful, it’s nothing. Without play, we wouldn’t be anywhere. Play is incredibly important; it’s deeply serious as well. It’s hardly a criticism of my work to call it playful; on the contrary, it’s flattering!” I asked him whether there was a sense back there in the early seventies in which the growing technical mastery was no longer allowing the earlier playfulness, and he agreed. “Yes, yes, it’s true. I couldn’t play in that space, and it’s only by playing with the space in the years since then that I’ve been able to make it clearer. Everything since then has been a progression toward a playful space that moves about but is still clear and not woolly.”

At the time, back there in the midseventies, all he realized, in his own words, was that “‘No, no, you cannot go anymore in this direction.’ I knew that. I didn’t know how to deal with it, so I just slowed down, and I moved into the theater. The first opportunity to do the staging for an opera came up about this point, Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress at the Glyndebourne Festival in the summer of 1975. I took this opportunity to work in a different medium when they asked me, and immediately everything became fresher.”

In retrospect Hockney recognizes that one of the ways in which things became fresher was that stage design sprang him into a world of multiple and moving perspectives—sprang him, that is, clear of the constricting ensnarements of traditional one-point perspective. One painting he did during this period as a sort of spinoff from the opera, a product of his extensive researches into Hogarth’s original Rake’s Progress engravings, was a color rendition (1975) of the black-and-white engraving that Hogarth had provided as the frontispiece for an obscure treatise on perspective by one John Kerby (Fig. 22). “The original etching [sic] was a kind of visual joke, all about common mistakes in perspective,” Hockney recalls, “and I found it vastly amusing. The perspective was, of course, all wrong, but what was fascinating was that it still worked as a picture. So I made my painting, although at the time I did it, I did not yet realize what that painting was all about. It took me almost ten years to understand how, for instance, the reverse perspective in the foreground, far from being a mistake, gives the image greater reality.”

FIG 22 David Hockney, Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge, 1975.

The mid- and late seventies were the period when Hockney was becoming increasingly involved with Picasso and with cubism, but that involvement was only gradually and grudgingly revealing its lessons. In the meantime Hockney was continuing to try to make his paintings work.

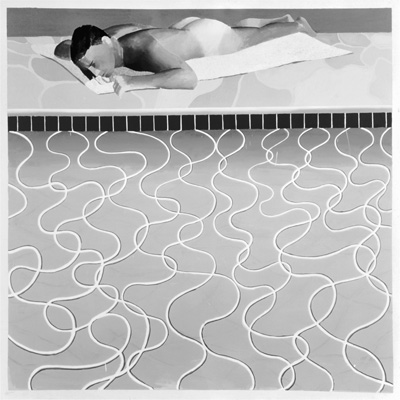

“I’d moved to Los Angeles and was working on a painting of the view outside my studio on Santa Monica Boulevard,” Hockney recalls. “And it wasn’t working [Fig. 23]. It was still stuffy, still asphyxiated by that sense of supposedly ‘real’ perspective. Eventually I gave it up. At the same time, though, I’d now moved up here to this house in the Hollywood Hills, and I began a painting depicting the drive down to the studio. (This was before we built this studio up here, so I was working down there and driving there each morning.) The moment I moved up here into the hills, wiggly lines began appearing in my paintings. The only wiggly lines that I’d had in my L.A. paintings before that were those on water. Buildings, roads, sidewalks were all straight lines, because that’s what L.A. looks like in the flatlands: long straight roads, right angles, cubes. So anyway, I now began to paint this Mulholland Drive too, down there in the studio (see Plate 1). The one which I could see right out the window wasn’t working, but this other one which I was painting from memory—the memory of the drive down—was beginning to work. You see, it was all about movement and shifting views—although at the time I didn’t yet fully understand the implications of such a moving focus.”

FIG 23 David Hockney, Santa Monica Blvd., 1978—80.

In Mulholland Drive, “drive” is a verb.

“So that Mulholland Drive was working,” Hockney continued, “whereas Santa Monica Boulevard was not. And with Santa Monica Boulevard, I now understand, the problem was photography. I think it was necessary for me in a sense to destroy photography—or anyway what I thought photography was—to refute the claims it was making in order to be able to change for myself the whole notion of a painting’s being real, of what is real in the world of a painting. It’s taken a long time; it took me over five years. I had no idea it would take so long, not that I minded. I mean when people said I was wasting my time, I could care less. What I was learning was amazing to me. I realized more and more what you could do, how you could chop up space, how you could play inside the space, that only by playing could you make it come alive, and that it only became real when it came to life.” “We’ve spoken about a lot of this before,” Hockney pointed out, referring to our conversations at the time of the Cameraworks volume. “So we needn’t go over it all again. But the principal point, I suppose, is that the major problem with traditional perspective, as it was developed in fifteenth-century European painting and persists to this day in the approach of most standard photography, is that it stops time. For perspective to be fixed, time has stopped and hence space has become frozen, petrified. Perspective takes away the body of the viewer. You have a fixed point, you have no movement; in short, you are not there, really. That is the problem. Photography hankers after the condition of the neutral observer. But there can be no such thing as a neutral observer. For something to be seen, it has to be looked at by somebody, and any true and real depiction should be an account of the experience of that looking. In that sense it must deeply involve an observer whose body somehow has to be brought back in.”

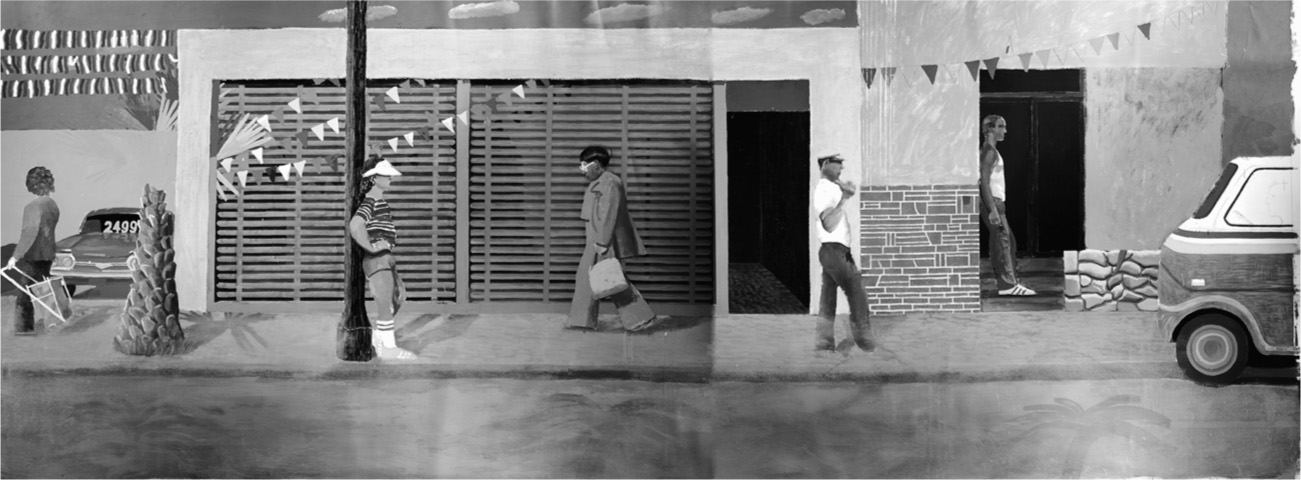

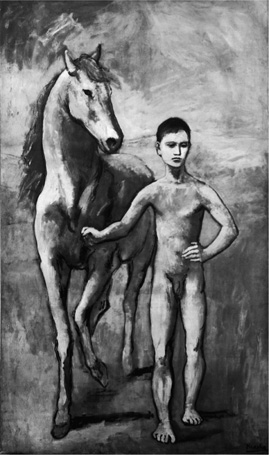

As far as Hockney is concerned, the initial cubist achievement was to make this case with devastating finality at the very moment of photography’s apparent triumph. It has taken years for the implications of that achievement to filter through, and indeed most cultural observers, not to speak of the vast majority of average citizens in the world of vision, have still failed to grasp those implications. “Most people, when you say, ‘realism,’ still think you’re talking about a certain way of seeing from a distance and in good, orthodox perspective,” Hockney explains. “When you say, ‘cubism,’ they think you’re talking about a particular historical style, a kind of painting, say, that was popular for a few years over half a century ago. I think one could mount a certain case against the Museum of Modern Art for helping to perpetuate that fallacy, for diluting the effects of cubism’s visual revolution by encapsulating it, confining it inside the walls of a museum (and even then, only certain walls in certain rooms, devoted to a particular historical moment), as if it need have no effect outside, as if movies or television or photography or politics or life could simply go on without someday having to be cubified. A while back, I was reading Hilton Kramer’s review in the New Criterion of the core installation at the new MoMA, and at one point he described the room containing both Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon [1907] and his Boy Leading a Horse [1905–6] and almost in passing he referred to the Boy Leading a Horse as ‘more realistic’ [Figs. 24 and 25]. Well, that’s, of course, what most people think. (You can imagine if even Hilton Kramer talks like that, what some high school teacher in Kansas is telling his students.) But it isn’t actually. That’s the point. It isn’t. And of course, this obviously means it’s still hard to see. No matter how much Les Demoiselles, for example, gets praised as a great revolution in painting,’ the revolution has still not truly arrived yet in the sense that it’s still not readable as being the more realistic painting, which it undoubtedly is. Juan Gris said that cubism wasn’t a style, it’s a way of life, and I subscribe to that.”

FIG 24 Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles dAvignon, 1907.

FIG 25 Pablo Picasso, Boy Leading a Horse, 1905—6.

Hockney then referred, as he is given to doing often, to a book he’d been reading recently, in this case Pierre Daix’s Le Cubisme de Picasso. Daix makes a similar point about the need to avoid seeing cubism in terms of “ephemeral fashions and short-lived schools” and then goes on to relate the power of its revolution “to the fact that physics was simultaneously destroying our three-dimensional space-time perception.”1 During the latter stages of his photocollage activity, Hockney now explained, he had himself been increasingly drawn to the terrain of modern physics.

“I was at a friend’s house in Canada,” he recalled, “and I was just browsing through some of his books about physics, and in one of them there were just two or three sentences that got me going. Coming back, I picked up several other books, and I found to my amazement that I could read them and follow their arguments. I mean, quantum physics is something way outside my ordinary understanding or involvement, but I quickly found incredible connections with the sorts of things I was concerned about. For instance, in the old Newtonian view of the world, in Newtonian physics, it’s as if the world exists outside of us. It’s over there, out there, it works mechanically, and it will do so with or without us. In short, we’re really not part of nature; it virtually comes to that. Whereas modern physics has increasingly thrown that model into question and shown how it cannot be. Mr. Einstein makes things more human by making measurement at least relative to us, or anyway, to some observer; the supposedly neutral viewpoint is obliterated. There can be no measurement without a measurer. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle is, of course, highly technical and specialized. It deals with a paradox in particle physics, showing how if you attempt to measure the velocity of a given particle you won’t be able to identify its exact location and vice versa. Previous to this, of course, science believed that given enough technical advancement, it would eventually be able to measure anything, but Heisenberg showed that this was not just a problem of not yet having the right measuring devices but that the problem was inherent in the nature of physical reality itself. The old conception of scientific inquiry had gone on as though we could measure the world as if we weren’t in it. Heisenberg showed that the observer, in effect, affects that which he is observing, so that some of those old borders and boundaries begin to blur, just as they do in cubism.

“But perhaps my greatest excitement along these lines,” Hockney continued, “came from reading a fairly recent book by a physicist named David Bohm, entitled Wholeness and the Implicate Order. Just a second.”

Hockney bounded out of his easy chair— out of the studio, down to his house, returning a few minutes later flipping through an obviously well-thumbed copy of the book. “Here, listen to this.” He proceeded to read a long passage from Bohm’s introduction.

“The notion that the one who thinks (the Ego) is at least in principle completely separate from and independent of the reality that he thinks about,” Bohm writes (and Hockney read), “is, of course, firmly embedded in our. . . tradition. . . . General experience . .. along with a great deal of. .. scientific knowledge . . . suggests . . . that such a division cannot be maintained consistently.”

After he’d read several paragraphs further into the text in a state of growing animation,2 Hockney put down the book, thoroughly invigorated. “You can see why I was so excited,” he said. “This insistence on the need to break down borders, to entertain the interconnectedness of things and of ourselves with things: the notion that in science today it is no longer possible to have ideas about reality without taking our own consciousnesses into account. And beyond that, just the language, which Bohm shares with a lot of other physicists. They’re always talking about ‘overall worldview,’ the need for ‘new horizons’ or ‘wider perspectives’ or ‘a new picture of reality’—all these visual metaphors which a painter of pictures can understand and which have relevance for how he thinks about his own pictures. There’s that famous phrase of Gombrich’s about the triumph of Renaissance perspective—‘We have conquered reality’—which has always seemed to me such a Pyrrhic victory, again, as if reality were somehow separate from us and the world now hopelessly dull because everything was known and accounted for. These physicists, by contrast, were suggesting a much more dynamic situation, and I realized how deeply what they were saying had to do with how we depict the world, not what we depict but the way we depict it.”

I asked Hockney whether he’d shown much interest in science in his school days.

“Not particularly,” he replied. “Not really. I was good at mathematics, but I think it was just the playfulness that attracted me. I didn’t do too much with it though. I think I took a rather general view of the sciences as somewhat cold and objective. I was going to be an artist, not a scientist, and those were two completely different categories. Finding out that they’re not that different has been very exciting for me. The more I’ve read of mathematicians and physicists, the more engrossed I’ve become. They really seem like artists to me. One’s struck how it’s almost a notion of beauty which seems to be guiding them, how at the frontiers of inquiry, contemporary physics even seems to be approaching and acknowledging eternal mysteries. Science is moving toward art, not art toward science. Of course, in an earlier time one spoke of the arts and sciences together, in one breath. Nowadays in the paper you get ‘Arts and Leisure.’ That just shows how far behind the paper is, as usual. But scientists and artists have all kinds of things to say to each other now.”

He suddenly laughed. “There’s something else I want to show you,” he said, getting up and walking over to a long countertop over to the side, rummaging around for a bit, and returning with another book, this time The Renaissance Rediscovery of Linear Perspective, by Samuel Y. Edgerton Jr.

“Here. I was just reading this this morning. Listen to this.” He read another long passage,3 in which Edgerton started out by suggesting that the invention of linear perspective had been partly responsible for setting the context in which Newtonian physics could both flourish and then, with the invention of progressively more “complex machinery” (also made possible in part by the existence of linear perspective), be superseded by “the new era of Einsteinian outer space.” Edgerton concluded by predicting that this new era might one day come to invalidate linear perspective itself: “Surely in some future century,” Hockney read, “when artists are among those journeying throughout the universe, they will be encountering and endeavoring to depict experiences impossible to understand, let alone render, by the application of a suddenly obsolete linear perspective.”

Hockney set the book down. “A lot of good stuff there,” he said. “The reason I laughed, though, is that last paragraph. I mean, I guess I hold with Buckminster Fuller’s comment, you know, when as an old man he was asked if he was sorry that he would never live long enough to experience travel in outer space and he replied, ‘Sir, we are in outer space.’ The idea that outer space is over there and we’re not part of it is silly. We’re already journeying throughout the universe. It’s like how I can never seem to get interested in space movies, because they always seem to me to be about transport and nothing else. Well, transport is not going to take us to the edge of the universe, though an awareness in our heads might. Transport won’t be able to do it; it’s like relying on buses. But the Einsteinian revolution, like the cubist, has already done it. Now we just have to open our eyes and see.”

Hockney’s comments, especially about Heisenberg, reminded me of a point the late anthropologist Jacob Bronowski made in his TV series, The Ascent of Man. Crouching down in an open field at Auschwitz, digging with his arm into the muck and mud of the place, he pointed out that in one sense Heisenberg during the 1930s had been proving the impossibility of absolute certainty and conversely the need for tolerance of multiple viewpoints (Bronowski even called Heisenberg’s the Principle of Tolerance) at the very moment that Hitler was propounding his dogma of absolute certainty.

I mentioned Bronowski’s formulation to Hockney, who was silent for a moment and then took it a step further. “It’s not just that,” he said, “because Heisenberg’s and Einstein’s physics actually led in two distinct directions. One of them, the more creative aspect, advanced this wider vision, the tolerance for multiple perspectives, which we’ve been discussing; at the same time though the other, the older, more straightforwardly technical side, was utilizing some of the ideas simply to make bigger and bigger weapons for our old myopic viewpoint of the world.

“Cubism is important for a lot of reasons,” he continued, “not the least of which is that it points the way to a greater tolerance and interdependence of perspectives in a world where failure to learn such lessons could have terribly dire consequences.”

From twentieth-century physics it was an obvious progression to fourteenth-century Chinese scrolls, obvious to Hockney anyway. “I want to show you something else,” he said, returning to the long countertop, rummaging about again, and coming back with another book and a long rectangular box.

“Around the same time I was beginning to get into all the physics books,” Hockney recounted, “I happened to be browsing in the bookshop at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis—let’s see, this would have been late 1983 or so—and I came upon a book called The Principles of Chinese Painting, by George Rowley, very dull cover. I thought, ‘Well, most Chinese painting looks the same to me.’ But I opened it, noticed the chapter headings, and one of them was called ‘Moving Focus.’ So I started to read it, bought the book, brought it back to the hotel, and got more and more excited.”

What was exciting him about it?

“Well, the attack on perspective. You realized it was an attack on perspective—it was all about the spectator’s being in the picture, not outside it—an attack on the window idea, that Renaissance notion of the painting’s being as if slotted into a wall, which I’d always felt implied the wall and hence separation from the world. The Chinese landscape artists, with their scrolls, had found a way to transcend that di‹culty. In my own photocollages, some of the ones I’d done on my trip to Japan earlier that year, I’d been pushing the notion of the observer’s head swiveling about in a world which was moving in time, but I’d really only just begun to try and deal with how to portray movement of the observer’s whole body across space. And that’s precisely what these Chinese landscape artists had mastered, according to Rowley. Here, listen.”

Hockney proceeded to read me a passage that was indeed highly suggestive.4

“You can see how relevant that sort of talk was to my concerns at that point. A short while later I happened to be in London, and I went to see some of the scrolls at the British Museum. And then I came back to New York to work on some prints up at Ken Tyler’s studio up in Bedford Village, about fifty miles north of New York City, and I’d occasionally come into the city and visit the Chinese scrolls department at the Metropolitan. There was a very nice curator there named Mike Hearn, who was assigned to show me some scrolls. That first day I got very excited and was telling him why, and that was getting him excited because normally, he said, he’s only showing scrolls to people in the Chinese scroll business, and I was talking about something altogether else. Most of them, the connoisseurs in that field, talk about the exquisite brushwork and the hand. Perfectly good things to talk about—in fact, I saw a direct connection in that regard to the late Picasso, in which all the activity of painting is made visible, not hidden in layers as in a Dufy, but all very clear and transparent—but it was the way of seeing that fascinated me. Meant the viewer participated. Here, look.”

Hockney reached for the rectangular box. “This is a reproduction of a Chinese scroll, which the Japanese have started to make recently. You’ll see why they have to make a reproduction, because it’s not possible to see this in a book, or for that matter in a museum, where it’s all spread out and the effect is destroyed. You have to be able to unroll it in your own hands over time. This would have been a beautiful ivory or ebony box; in reproduction you get wood. Once you open it, instead of an elaborate silk thing covering it, you get this bit of nylon. And then here is the scroll: something, you realize, is going to unroll. Instead of an electric motor, I will provide the energy, and I can go back and forth. This is a reproduction of a fourteenth-century landscape done in what the Chinese considered all-color, which is black and white.” Hockney held the two staffs of the scroll about eighteen inches apart and began unfurling, loosening one side and picking up the slack with the other. “The point is, your body moves. See, you start here looking down on a village from a hilltop. And then, as you alter the edges of the picture, you’ve moved on in time, and see, here, now, we’ve moved down into the valley, skirting the edge of the village, and now here we’re looking up toward a mountaintop and, here, moving further—without any break, without panels, rather in a continuous flow of lines—we’re now on top of that mountain looking down onto this lake. . . .” Hockney continued for a while, narrating the journey.

“There you are,” he said, concluding the demonstration. “You’ve walked through a landscape. It’s a profoundly different experience from a Western landscape, which is still based on your standing stock still, really.

“Anyway, you can see why I became so fascinated. Mike Hearn showed me thirty or forty of them. The people there at the Met were themselves getting overjoyed, you know, at a practicing contemporary artist taking an interest in their arcane discipline. I ended up giving a little lecture to the staff there, you know, just twenty people or so. I think they believe they’re in a backwater in a sense; I mean, obviously loving it but suspecting that everybody else thought it was a backwater, and I think they almost did themselves. And here I was telling them that these scrolls had the greatest possible relevance to the most contemporary of concerns.”5

One thing that began to form in my mind as Hockney spoke was an analogy to the initial situation of the cubists. Back in 1907, when Picasso and Braque had wanted to break free of the tyranny of European Renaissance perspective, they’d drawn on non-European African sources. Here Hockney at a similar moment in his career was drawing on non-European Chinese sources.

“Yeah,” Hockney concurred, when I tried the notion out on him. “They’re actually the same source in a way though. If you think about the beginning of ‘modern’ painting, with Manet, what you see there is the beginnings of the influence of the East: Japanese prints being seen in Paris around that time and the artists being exposed to another way of seeing. Perspective was driving them crazy in a sense at the Academy and with academic narrative painting. Perspective was making it ridiculous. And here they were exposed to another way of measuring, of seeing, and they got excited: Manet, Van Gogh, and so forth. And the Japanese after all derive from the much older Chinese traditions. A generation and a half later the cubists were similarly drawn to the Africans. So that the beginnings of modern art in Europe are fundamentally anti-European.”

I pointed out that ironically this was happening at the very moment of peak European colonization and subjugation of those non-European cultures.

“Wasn’t it Ruskin who’d said just a couple generations earlier that there wasn’t a piece of art in the whole of Africa outside Egypt?” Hockney responded. “Well, obviously Picasso didn’t think so. Everything outside Europe now began to have a major influence on the trajectory of European art. They saw a fresher way, a way of making the observer participate more. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, with that strange evocation of those African masks, draws you into the picture: you as the observer have to start doing things to reconstruct the space. You are getting a more vivid depiction of the experience of reality. And yes, for me, those Chinese scrolls at that moment helped me clear to a new way of constructing such experience into my own work.

Hockney came back to Los Angeles and in rapid succession produced a large gouache on paper portraying a visit to the Echo Park home of his friends Mo and Lisa McDermott (1984) and then the major two-panel oil painting of a visit with his friends Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy in Santa Monica (Plate 12), both works heavily influenced by the Chinese scrolls and saturated with the temper of Uncertainty.

“In retrospect the gouache was still somewhat crude,” Hockney explains, “but with both of these works I was trying to create a painting where the viewer’s eye could be made to move in certain ways, stop in certain places, move on, and in so doing, reconstruct the space across time for itself. I was combining lessons from both the Chinese scrolls and my study of cubism. I mean, unlike the scrolls these were going to be large images meant to be seen all at once, but the thing was, what I was aiming for was that in another sense they wouldn’t be able to be seen all at once after all. They were filled with incident, but whenever you focused on any single detail everything else blurred into a sort of complex abstraction of shapes and colors, and the image as a whole was always primarily abstraction. This sense of multiple simultaneous perspectives was something I’d, of course, honed during my work on the photocollages.

“As I say,” Hockney continued, “the Visit with Christopher and Don was considerably more complex.” We were looking up at a large photographic reproduction of the two-paneled canvas (the original was then in storage in New York). Following the usual disclaimers regarding the hopeless inadequacy of any photographic reproduction’s conveying the experience of a large work, Hockney proceeded to use the photo as the basis for his description. “You see, it’s meant to be read from left to right unlike the Chinese scrolls, although there’s a kind of tribute to the scrolls in a sort of prologue, the yellow strip at the top of the canvas, moving from right to left, which represents Adelaide Drive in Santa Monica. When I drive up there, I always know when to stop because of the big palm tree, and then there, at the number 145, there’s the little driveway where they park their two cars—or anyway, used to. (Dear Christopher has passed on in the meantime.) From that position you look out over Santa Monica Canyon, which is painted in reverse perspective, so it clearly places you up there looking down. You then come down the steps, and they’re painted that way because it’s not you looking at the steps from afar, you are actually moving down them as you approach the entryway. You come into the living room, and there are those two wicker chairs, which you might perhaps recognize from the double portrait I did of Christopher and Don back in 1968 or from some of the more recent photocollages. Anyway, from the living room you can look out the window and you see the view of the canyon again, which means you’ve moved, you have to have, to be seeing it. We then make a little detour here to the left into Don’s studio, and there’s Don drawing. You can go upstairs and downstairs; you see the same view again from two different windows. Then coming back across the living room, moving rightward, you walk down a corridor, past the bedroom. If you notice, the television set, everything, is actually in reverse perspective, meaning you’re moving past it, seeing first the front and then the back. And then you walk right to the end, into Christopher’s studio and even past him, to the very end, at which point you’re looking back on Christopher at his typewriter. You know you’re looking back because he’s looking out through his window, and it’s the same view of the canyon. So there, you’ve reconstructed the space, and now your eye is free to roam about from room to room, taking in more details.

“It was a very di‹cult painting to accomplish,” Hockney continued. “The problem was how to prevent the eye from stopping, from getting stuck. For instance, that’s why both Don and Christopher are rendered transparently. When you look at Christopher, you see him, but when you move along to the bedroom and you’re looking at the bed, he dissolves in a sense into patterns of green and blue and red paint. If they’d been rendered solidly, your eye would have tended to fixate on them. Similarly I had to work through several versions before I came to understand that you couldn’t have too many verticals or horizontals. (There are too many in the other one, the gouache of Mo and Lisa’s; that’s one of the problems with it.) In fact, every time a right angle appeared, it seemed to stop the eye’s moving. It’s all very carefully constructed, even though it might look like chaos at first.”

I returned to an earlier question. Didn’t this particular oil painting, for example, represent a culmination of sorts, a more significant achievement than some of the same period’s works in other media?

“I don’t know,” Hockney replied. “I don’t think so. I mean, you’re asking me a question I wouldn’t normally think about too much. What you’re aware of, I suppose, as the years pass, you might recognize that certain works were key works in that you realized that you really discovered something there.

“For instance, the photocollage of walking in a Zen garden, from 1983. It was the most radical one up to that point, and it’s the most radical one in the Cameraworks volume. I’d first done that earlier version of sitting in a Zen garden [see Fig. 16], where the sense of perspective was very strong—the rectangle of the rock garden almost read like a triangle, the perspectival V was so strong. And I started gnawing on this question of how one might present the garden as the rectangle it actually was. I mean, in drawing it would have been easy, and I suppose that with a camera one could have rented a helicopter and shot it from above looking down, but any picture you got that way would have mainly been about being in a helicopter, and I wanted to do something about the rectangular quality of this garden. And then it dawned on me that if I moved along the length of one rim of the garden and snapped a row of shots every few steps, scanning from my feet on upward toward the far rim, I’d eventually be able to solve my problem. And as you know, when I got back to L.A. and had the shots developed and assembled the collage [see Fig. 17], I grew very excited. My first thought was that I’d made a photograph without perspective. Comparing it with the earlier collage of sitting in a Zen garden, this one of walking seemed to me truer, not the truth, but truer. And I also realized that with this one the viewer was moving through space.”

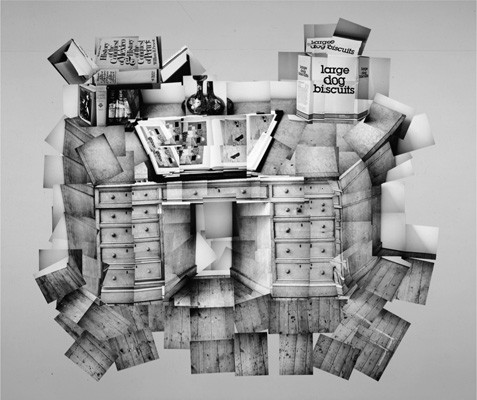

FIG 26 David Hockney, The Desk, July 1st, 1984.

Were there other breakthroughs?

“Well,” Hockney continued, “the Zen garden collages came before the Chinese scrolls. A year later, after the scrolls, I did The Desk [1984, Fig. 26], and that was a very important piece for me because there I was really learning to establish an object in space.” He pointed to the poster version of the desk collage tacked to the wall. “As you can see, it’s in reverse perspective, which means you’re moving about it, seeing it from one side, then the other, coming up close and looking down on it, and this opened up all sorts of possibilities for me. I’d done a space, which was the Zen garden, and now a solid object, this desk, and now the challenge was to find some way of putting them together: the object inside the space. That took time too, but in a way that’s what the Visit with Christopher and Don painting is about and then later the big Pearblossom Highway photocollage as well.”

Hockney continued looking up at the poster of The Desk. “The thing about reverse perspective . . .” he began and then paused. “I mean, my argument has always been that in traditional perspective infinity is a long way away and you can never meet up with it. Whereas if you reverse perspective, infinity is everywhere and you are part of it. There’s a vast difference in the two viewpoints, a totally different way of looking at the world. You haven’t just reversed a little game, you’ve reversed a whole attitude toward life and physical reality.

“Furthermore,” he continued, “the traditional Renaissance way is by no means the natural one. You have to be rigorously trained into accepting its conventions; the misperceptions have to be drilled into you. Look at how a child draws a house— you get the front, the sides, the back, the backyard tree, everything all jumbled together—and then the teacher comes and says, ‘Wrong, wrong. You can’t see all those things at once. Do it this way instead.’ But in a sense the child was right in the first place; his version was more alive, and the teacher’s is a more impoverished rendition. Or, for instance, a child draws a landscape, and he draws the earth at the bottom of the piece of paper, a brown line, and the sky at the top, a blue line, and a tree in the middle, perched on the brown line of the earth. And the teacher comes along and says, ‘No, no. Wrong. You don’t need two lines because, well, there’s only one line, in the middle, where the sky and the earth meet.’ Which is true in a way, but it also fails to acknowledge the piece of paper. What the child has done is taken that piece of paper and said, ‘When you look up at the sky, that’s the top of the page, and down at the ground is the bottom. And that is an exact translation of sky and earth made onto a piece of paper. The other way you’re looking through the piece of paper, as if it weren’t there. But the child knows it is there and is dealing with that surface, at least until the teacher teaches him not to see it.”

As Hockney was speaking, I was again reminded of the childlike quality of much of his early work from his Boy Wonder period in the late fifties and early sixties. I asked him whether he’d been dealing with these sorts of issues even then. “Not in so many words,” he replied, “not in these terms. But I have recently been looking back over some of that work, and there are certain striking continuities, things which I’ve only just now become able to see.

“One of them, for instance, occurred to me a while back when I was reading David Bohm’s book, where he talks about how borders must be broken—‘for every border is a division or break’—and it occurred to me that probably the most consistent theme in my work is actually that. For instance, there’s a little painting from 1962. What happened was that a friend of mine had bought this very elaborate little wooden frame, and I said, ‘What are you going to do with that?’ He said he was going to put a mirror in it or something, and I said, ‘Oh, don’t do that. I’ll make a painting for it; it seems such a shame, such a beautiful frame.’ But what I painted in the frame was a little man, wedged in tight, who’s touching all four sides of the picture, and he’s shouting, ‘Help!’ In short, he’s really trying to get out of the picture frame [Fig. 27].

“Or think of all those early paintings of curtains. People say, ‘Oh, they’re about the theater.’ But you can also read them in another way, for the figures are standing in front of the curtain, which means, again, you’re breaking an edge. There’s the edge around the four sides, but there’s also the implicit edge in front, the glass separating the painting world from the world of the observer. And in some of those early paintings—for instance, Play within a Play, from 1963 —the figures in the painting are desperately trying to cross over that boundary [Fig. 28].

“The theme occurs throughout my work,” Hockney went on. “For instance, in the stage designs. In the last piece of theater work I did before this Tristan, the Stravinsky triple bill back in 1981 at the Met, we did The Rite of Spring followed by Le Rossignol followed by Oedipus Rex. And what we did was, The Rite of Spring was staged way at the back of the stage; Le Rossignol was almost like Italian theater, with the proscenium all around it; and by the time we got to Oedipus to make it like Greek theater, we lit up the proscenium, which had the effect of making that into the set; the whole theater becomes the set, which again is breaking a border, breaking an edge. And you begin to realize what edges do: they’re not just showing us things; they’re cutting off far more than they’re showing us. The edge is the problem. It’s the major problem we have to deal with. I mean, it will always be there, but it can be softened with different ways of looking, a more complex image, and that’s what we now need to do.”

FIG 27 David Hockney, Help, 1962.

Back in Play within a Play, what Hockney had been playing with was the notion of a figure—the painted rendition of a character looking remarkably like himself— trying to step out from the rigidly perspectival world (note the floorboards) of the painting. He can’t do it; his face literally gets smudged up against the imaginary glass of the Renaissance windowpane. In his latest work, though, it’s as if Hockney had reversed the terms of the problem. The world of the painting no longer has to get out to reach the observer, because the observer has gone in.

FIG 28 David Hockney, Play within a Play, 1963.

“In Pearblossom Highway,” Hockney now commented, “which is far and away the most complex and the most successful of the photocollages I’ve done so far (see Plate 11)—it took me over nine days just to photograph and another two weeks to assemble—the results are quite powerful, I think, in the sense that you’re deeply aware of the flat surface but at the same time you start making a space in your head. And yet the space is not the illusionistic kind where you feel, ‘Oh, I could walk into that,’ which is the old type of illusion and sort of a cheat or a contradiction anyway. You’re saying, ‘Oh, I could walk into that’—only if you tried, you’d kill yourself or you’d hurt yourself anyway; you’d be walking into a brick wall. No, here you don’t feel you need to walk into it because you’re already in it.

“That’s what my most recent work has been about essentially,” he continued, “Pearblossom Highway, the Home Made Prints, the paintings which I’ve been able to do the last few weeks based on some of the lessons about surface I’ve gleaned in doing the photocopy prints. Take a look at Pearblossom, and then take a look at a standard photographic rendition of the same scene [Fig. 29], and you realize that you’re beginning to deal with a more vivid way of depicting space and rendering the experience of space.”

I’d been meaning to ask Hockney something almost since the moment of my arrival (although I had been a bit shy about doing so), for there had been a striking change in his physical appearance since the last time I’d seen him several years earlier; he was conspicuously wearing a hearing aid. Actually he was wearing two hearing aids, one in each ear. And now I did ask.

“Well,” he replied, “I first realized I was losing my hearing back in 1979. I was giving a seminar in San Francisco, and I kept having to tell the people in the back of the room to repeat their questions; I couldn’t hear them. I could see that everybody else could hear them, and I thought, this is strange. I went to have my hearing checked, and they told me I’d already lost twenty percent. They gave me a little hearing aid, but I didn’t use it much, didn’t think about it much, and eventually even lost the thing. But the hearing loss was having an effect apparently—I was getting more antisocial, in a way, because I just couldn’t hear people—and it was getting worse. Sounds were getting both dimmer and more blurred. So in 1984 I went to some specialists, and they all told me the same thing, that it would continue to get gradually worse, there was nothing you could do to arrest it really, but that a more sophisticated hearing aid would help. So I got one, and the moment I put it on, it was like a big mu›er had been taken off my head. The guy had said either ear would do since they’re both the same. So I went back, and I said, ‘I think I’ll take two actually.’ He said not too many people put two on; they think it looks too bad, makes you look old. I said, ‘I don’t really care what it looks like. I’d rather hear.’ I mean, I’m not vain in that way. I wanted him to make me a red one and a blue one.”

Mismatched, like his socks.

FIG 29 Pearblossom Highway, Palmdale, California, April 1986.

“I mean,” he continued, “you’d have to be daft to think that nobody’s going to notice it. But who cares? People come up to me now, and they ask, ‘Have you got hearing problems?’ and I say, ‘Well, I used to have, but I don’t now.’ It’s made a world of difference. Everybody comments on how my body movements have changed: I don’t lean over, I can lie back and listen, I don’t have to be watching people’s faces, lip-reading.”

The first half of the 1980s, the period when Hockney was struggling with his hearing, also happens to be the time when he was becoming increasingly consumed by his renewed investigations of visual space. I asked him whether he thought there was a relation.

“Well,” he said, “of course, hearing is spatial. It is spatial in its essence. It helps you define space—somebody is speaking behind you, there’s a noise over to the side—it helps give you your bearings in the physical world. Surely as my hearing began to grow mu›ed, I was having to rely more on my vision. There’s the old truism regarding blind people that they use their hearing to help locate themselves and that therefore they probably develop more acute hearing. Well, the reverse must also be true: a loss of hearing ought to lead to more acute vision and in particular visual perception of space. Ordinarily nobody would know, nobody could see the change, unless you were somebody who used vision in some particular way, say, as an artist. So, sure, I think that has been an important influence in the past several years.”

At this point in our conversation Stanley came barging in. Well, “barging” is a bit strong. Trotting? Scampering? Slip-and-sliding? There was a lot of yelping involved. He was still a pup, and coordination was not his strong suit. Hockney scooped the baby dachshund into his arms, nuzzled him close to his cheek, and then carried him back over to the photocopying machine to have a look at the just completed portrait.

“This is little Stanley,” he explained, “named after the Great Stanley, of course.” David cocked his head in the direction of a small oil portrait, hanging on the wall, of Laurel and Hardy. That portrait was the work of David’s father, who’d been a huge fan. “Everybody’s been surprised I got a dog. All my friends are shocked. I don’t know why. But one reason I never had animals was that for many years I lived like a gypsy—I was always going off—and you can’t, for example, take a dog in and out of England. Even the queen can’t. So I didn’t even entertain the thought. But recently my friend Ian got a little pup, which I loved—did a portrait. And then a few months later, Ian said, ‘He’s going to have some little brothers in another litter.’ And suddenly I thought, maybe I’ll get a dog. So I went over, picked Stanley out—he was only about this big—brought him home. He looked frightened to death. I put a rubber ball in front of him, he just stood there looking at it, and I did a painting of that. At first I thought, ‘Oh my God, what have I done? I’ve made a terrible mistake. I’m going to have to fuss around. I won’t be able to go anywhere.’ But the problem is, within three days you’ve fallen in love with this little creature, you realize how, you know, he’s relying on me, he wants to sleep in the bed, he puts his little head on the pillow next to mine. Clearly he either thinks I’m a big dog or he’s a little person. I don’t know which. But I love him actually.”

It was interesting, I pointed out, reflecting on Hockney’s comment about his former gypsy life and recalling his earlier allusion to Buckminster Fuller, that at the very moment his work was shooting off into outer space, as it were, he was taking on anchors that were going to tie him down to home.

“That’s it,” Hockney agreed.

And Stanley was the icon that represented . . .

“That makes me stay here.”

He was able to deal with Stanley because he’d achieved that centeredness ?

“I’ve got an excuse to people: Stanley is here. I can’t possibly leave Stanley. And actually I’ve got a lot to do. There are a hundred things I want to be doing. I’m going back into painting; I can feel it coming on strong. I want to stay in one place now. It’s mad to always be going off. I’m going to be fifty next year . . .”

Was turning fifty going to be important for him? The retrospective was going to be touring during his fiftieth year.

“Well, I don’t see it as a retrospective. I just see it as work done up till now, that’s all. Fifty doesn’t make any difference to me, although I did laugh at Nick Wilder’s comment the other day. He went to somebody’s fiftieth birthday, and they said to him, ‘Oh, come on, fifty’s only middle age,’ and he said, ‘How many do you know of a hundred?’

“But I’d rather be isolated to do what I want to do now. There’s a point when you’re young and you need other artists; you feed off other people’s ideas as well. But there comes a point when you have to sort stuff out for yourself; you don’t need the stimulus anymore. You’ve had enough actually. I’m aware of that now. I’ve quite enough stimulus these days from myself. I also enlighten myself. I don’t mind if I never go out. I don’t mind if I never get invited anywhere. I amuse myself. Especially with Stanley. Because I need to talk to myself out loud, and before I felt a bit of a fool. So naturally Stanley can hear all the lectures now. He listens, and he keeps coming back for more.

“Like I say, one of the main reasons I used to travel was to get away from all the nattering. But I won’t have to be worrying about the natterers anymore. Stanley’s going to growl at them when they come to the door.”

This essay was written for the catalogue of the retrospective exhibition held at the Tate in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in 1987.