We are nearing the end of act 3 of Wagner’s Tristan, and David Hockney has the volume jacked way up.

Intently hunched over the control panel, facing his intricately fashioned miniature stage model—one of three such lightboxes (one for each of the three acts, on a scale of one to twelve, or one inch to the foot) mounted atop adjoining flatbed tables in the hangarlike space of his otherwise darkened Santa Monica Boulevard studio—Hockney is deep in preparation for the upcoming revival of his 1987 production of Tristan und Isolde at the L.A. Opera (slated for nine performances in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion this January and February), and as his hand glides expertly up and down the dozens of slide knobs on his command console (each pegged to its own miniaturized bulb inside the box), he is matching Wagner’s motif shifts, uncannily, light for leit (Plates 13–15).

Indeed the experience is like nothing so much as one of those “Parsifal drives” on which Hockney famously used to take visitors to his Malibu outpost, one at a time, about a decade ago, around the time of his first Tristan’s vernissage. You’d be sitting there in his glass-enclosed porch, sipping tea and gazing out over the roiling surf as the late afternoon sun arced toward the horizon, when Hockney, glancing up at the clock, would suddenly announce, “It’s time: Let’s go.”

You’d follow him out to the garage, climb into the passenger seat of his fire engine red Mercedes convertible as he slid behind the wheel, lowered the top, and presently eased the car out into the flow of upstream tra‹c on the Pacific Coast Highway, at which point he’d take to punching a set of mysterious buttons arrayed along the dashboard. Suddenly music would come welling up all around you (for typically Hockney’s Mercedes was one of the very first vehicles anywhere to be fitted with what was then an experimental onboard CD player, its ten-deck platform secreted in the trunk of the car): a rousing Sousa march for starters and then (as Hockney’s fingers raced authoritatively across the buttons) Bernstein, Gershwin, the “Blue Danube”—brief perfectly chosen passages from each until he veered off the main highway onto one of those steep side roads that wend their way high into the Santa Monica mountains, at which point (another hand pass over the buttons, a downshift of the gears) the music would segue into Wagner, as up and over that initial incline you’d be cruising and then down upon the first unexpected valley vista: the Entrance of the Gods into Valhalla. And so on, across that valley and up its far purpled slope, through one perfectly chosen Wagner passage after another, Hockney pacing the car just right so that Wagner’s transitions seamlessly matched the road’s own curves and croppings, and the constrictions and the dilations of the endlessly changing view. Mainly orchestral passages from Parsifal, as you looped in and among the canyons and then finally back up the main spine of the mountains for the return toward the shore. And if Hockney had managed to time things just right—and usually he had—the music itself would now be reaching its most thrilling climax yet (Siegfried’s funeral), exactly one hour and twenty minutes into the drive, just as the car rounded a final bend, suddenly divulging a stupendous sudden view of one last valley at the very moment the sun was sinking behind the far darkened slope.

So that it can get to be like that, sitting beside Hockney at his control panel as he whizzes along, putting his miniature set through its lighting paces—only, louder: much louder. Tristan in his death throes swells ever more deliriously. (“What,” he is singing, uncannily, “do I hear the light?”) Louder and louder and louder. But not loud enough.

For now Hockney is really going deaf.

And after over twenty years of repeatedly taking entire auditoriumsful of opera lovers throughout the world on the sensory rides of their lives, these upcoming nine performances at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion may well come to constitute Hockney’s last such forays ever.

Tristan und Isolde: Beethoven meets Matisse.

A few minutes earlier, on the neighboring lightbox, Hockney had been demonstrating the effect he was aiming at for the incomparable love duet at the center of act 2. Tristan, King Mark’s most loyal and beloved knight, has fallen hopelessly in love with the king’s bride, Isolde, as she has with him, and the two contrive a secret rendezvous just outside the castle walls in the middle of the night while the rest of the royal party is off on an all-night hunt in the encircling forest. Night, in Wagner’s conception throughout this opera, is the realm of true passion, blissfully oblivious to the duties of the day. And in Hockney’s version, as the lovers initially approach one another, tiny lights begin to flicker all about them in an otherwise pitch-black surround: they are, we are given to feel, as if lost in a universe of their own. (Later, as the dawn begins to rise, the twinkling lights will gutter out as the deep expanse of castle wall and girdling forest gradually make themselves evident, an astonishingly beautiful and satisfying space, in Hockney’s magical rendering, but at the same time one that is somehow claustrophobic, constrictive, and saturated with threat, since we all realize that at any moment the king and his party may come barging in from out of the forest onto this daytime-scandalous scene.)

“I can’t hear the low notes anymore,” Hockney sighed, disconsolate, at one point. “The cello: I know it’s there, I remember it, but I can’t hear it.” Hockney’s condition is genetic, progressive, and inexorable—his father gradually went stone-deaf, and his older sister has likewise been doing so, just ahead of him: there’s nothing to be done. For years now Hockney has been sporting hearing aids in both ears, but their effectiveness is beginning to fall off precipitously. “I really noticed it a few weeks ago in Australia,” he recounted, referring to a visit to Sydney, where he’d been supervising a revival of his 1992 staging of Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten. “Whole swaths of the music: gone. And coming back, what with all those hours spent in the pressurized cabin of the jetliner, I couldn’t hear a thing for a whole day. I just went to bed.”

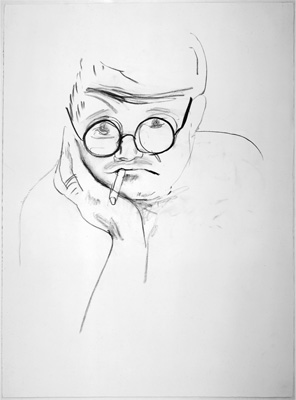

Earlier he’d shown me a suite of recent self-portraits, quick-study paintings he’d been producing over just the last few days, and they were, for Hockney, uncharacteristically glum (Fig. 30). Or not glum, exactly: dumb, or rather dumbfounded, questioning, stock-stilled, slack-jawed, stumped. I’ll be stumped, they seem to say, and the stump in question is specifically the ear, one of which is conspicuously missing, as if sheared off the side of his head.

FIG 30 David Hockney, Self-Portrait with Cigarette, 1983.

And yet such desolation—the sense of being, in a way, in a sense, at a loss—is usually a passing mood with Hockney: his is a celebratory sensibility, little given over to brooding despair. In Wagnerian terms, it is the daytime duties that truly seem to vivify him; if anything, his is more of a Mozartian presence. (One is reminded of his crisply playful staging of The Magic Flute, one of his first such efforts— in Glyndebourne, back in 1978—another tale of the passage from night to day, though with all the polarities reversed, such that daytime there implied not a reversion to bland conventionality but rather the hard-won achievement of blessed enlightenment.)

Beyond that, it’s as if everything for Hockney—even any given diminishing sensory capacity—feeds the wider creative enterprise. It was not lost on Hockney, as early as ten years ago, around the time of the first Tristan, how, with hearing being spatial, a loss of hearing ought to lead to more acute vision, in particular, visual perception of space.

He made a similar point on this visit, noting how he’d recently been reading the second volume of John Richardson’s biography of Picasso and had even sent Richardson a note, speculating about the possibility that Picasso may have been tone-deaf. “I mean,” he explained to me, “he didn’t go to concerts—Braque, by contrast went to concerts and band performances all the time—he didn’t respond to music, couldn’t fathom its greatness, meaning he couldn’t hear it, it didn’t mean anything to him. And I just find myself wondering whether such tone-deafness might help account for the amazingly confident grasp he had of chiaroscuro, as opposed to, say, Braque— the deeper sense of pictorial space in his cubism than in Braque’s.”

If hearing is spatial, it’s temporal as well—by definition, and in a sense more radically so than vision. And if the challenge Hockney’s been setting himself in almost all of his labors over the past few decades has been how to evoke (whether through photocollages, on the canvas, or across the stage) a lived sense of deep space and deep time, it’s perhaps not so surprising that throughout this process, his studio work and his stage work have been in a constant state of interpenetration.

Opera, of course, has been wonderfully evocative for him in this regard— “Naturally,” Hockney agrees. “After all, it is an art of time”—though his earliest stagings, back in the late seventies, still tended to a certain stylized flatness. In fact it was only with the original Tristan production, undertaken as his neocubist photocollage explorations were reaching their peak, that Hockney seemed to punch through to a new sense of spatial and temporal depth. He started approaching the entire project more as a lighting designer than as a set or costume man. The focus was no longer so much on creating spellbinding sets—flats, as they’re called—as on raking lights across them through time, in time, of course, with the music, in an art of startling synesthesia. (There were moments in Tristan, and in Turandot after that, when the entire stage seemed to blush, and you, in the audience, in physiological response to the sudden barometric shift in sight and sound, blushed right back.)

All the while Hockney has been trying to find ways of introjecting this new sense of spatial depth back into his studio work. One of his more intriguing efforts in this regard was on display earlier this year at the André Emmerich Gallery in New York, a room-size installation in which Hockney had luxuriantly painted both the far wall and the intervening floor with sworls of brightly colored abstract landscapes, set against an otherwise blackened surround (Fig. 31). A bank of four highly sophisticated stage lights, recessed into the ceiling on computerized pivots, individually panned the space, their colors and densities endlessly changing in infinitesimal patterns, across a meticulously programmed ten-minute loop. Hockney dubbed the piece Snails Space— a marvelous pun, slurring as it does the distinction between space and pace, between three dimensions and four. An opera without sound, I remember thinking, delighted, at the time. Or else: Music for the deaf.

FIG 31 David Hockney, Snails Space with Vari-lites, “Painting as Performance,” 1995-96.

Hockney’s most recent paintings, apart from the self-portraits, have been a series of cut-flower groupings (Plate 16), couched in a luminously clear and deepening space, and he’s been talking about them as exercises leading toward a return to the two-figure paintings that once constituted the core of his work but which he largely abandoned, many years ago, in frustration over his inability at the time to break free of the straitjacket of conventional photographic space. Tristan and Isolde (I now found myself thinking, as he described these ambitions to me), alone on the stage.

In all of these endeavors, though, Hockney has increasingly been like a man who has been forced to look listeningly. And who has heard.

The first time around with Tristan somebody had the bright idea of pairing Hockney as designer with his compatriot and virtual contemporary Jonathan Miller, the neurologist and theatrical polymath, as director. (The L.A. Opera’s general director, Peter Hemmings, takes both the credit and the blame.) It was a mismatch almost from the start. Although neither man is a raving prima donna, both are perennial boy wonders with often overpoweringly headstrong and definitive visions. In this instance, Miller soon came to realize that faced with Hockney the celebrity, working on his home turf, he wasn’t going to get a concept in edgewise. (“I’d clearly been brought in as a sort of real estate agent,” Miller jokes about the experience nowadays, “my brief being limited to showing people about the premises.”)

Going into his collaboration with Hockney, Jonathan Miller had been struck by the strangely static quality of the opera’s action: “The challenge is to figure out some way to galvanize the stage,” Miller noted, when I reached him by phone at his London home, “for hardly anything actually happens. The music, of course, is quite moving, but in the famous duet scenes, for instance, there’s hardly any love at all—you can’t have them thrashing about, screwing, because there is none of that in the text, though it does get alluded to. It’s about something odder, deeper, stranger: this peculiar protofascist feeling that pervades the whole, like some SS o‹cer’s wet dream. That’s what it’s about, really, this strange anthropophagus woman swallowing up, unmanning this dutiful knight with her magic potion, and then all that weird stuff about Tristan’s endlessly dying, through the entirety of act 3, from the septic wound he contracts at the end of the second act. What’s all that about? Not that it’s fascist in itself, but it belongs in that sort of world, against that kind of backdrop—you can see what appealed to the budding Nazis. You can just hear them humming the music in their heads. I was even thinking of trying to set the opera in the world of Germany of the late twenties or early thirties.”

You can see how Jonathan Miller’s and David Hockney’s conceptions were never going to converge.

This time around, Hockney himself, his encroaching deafness notwithstanding, is listed as both the designer and the director (although he is being assisted in the latter capacity by Stephen Pickover, who will be credited with “staging”). Hockney insists that the two roles are really one in any case, and that in both instances he’s simply trying to serve the music itself.

“One of the first things Jonathan Miller did when he arrived here to begin work on the opera”—David Hockney still can’t get over this; he loves regaling people with the tale to this day—“was to announce, confidentially, ‘Silly story!’ Which, I mean, is amazing. Because the story isn’t the words—though the librettos are what most directors seem to spend most of their time mucking about with, plumbing them for motivation and so forth—it’s the music. It’s in the music. When I start work on an opera, I maybe read the libretto once, but then I set it aside and hardly ever go back to it: I just listen to the music over and over and over again. And the story Tristan’s music tells is anything but silly. It’s overwhelmingly moving, really. It’s ravishing.”

Ravishing is a good word, and it set me to recalling something my mother once told me about her Viennese grandmother, how from certain dainty late-life conversations she’d had with the banker’s widow about marital duty and marital relations, she’d become convinced that the old dowager had never in her life experienced an orgasm while engaged in physical relations with her husband (the only man, for that matter, she’d ever had such relations with)—“Just the way she talked about things,” my mother would recall, “the curl of distaste, of put-upon, vaguely contemptuous, indulgence.” Not that my great-grandmother had failed ever in her life to experience physical ecstasy, my mother continued: like many of her contemporaries among the high bourgeois wives of Vienna at the turn of the century, she was a Wagner fanatic—she claimed to have witnessed Tristan alone almost a hundred times, often by herself or else accompanied by other women friends at matinees while their husbands were off at work (or, perhaps, frequenting brothels?)— and from the way she talked about that, my mother was convinced that she was regularly being ravished, to the point of physical climax, right there in the august, chandelier-decked vault of the theater.1

For all his demurrals, Hockney never had an approach as purely aesthetic, music-centered, or otherworldly as he himself avers, either at the time of its first production or this time around. This realization came back to me with renewed force now as, watching David coax his lightbox through the last minutes of act 3, I was reminded once again of the world of those first performances back in 1987.

If Tristan’s second act traces the progress through a single love-besotted night, from oblivious darkness into the glaring revelations of dawn (culminating as the scandalously discovered, death-seeking Tristan throws himself onto the outthrust sword of King Mark’s other dutiful knight, Melot), act 3 by contrast traces the progress of a single day, from dawn through scalding noon to long-sought fall of night, as Tristan, returned to a stark promontory overlooking the waves near his home castle in Brittany, thrashes in fevered anguish, deliriously awaiting the seaborne arrival of Isolde, who either is or isn’t coming with the medicinal balm that alone can salve his gaping wound. (Through wonderfully subtle and cadenced changes of lighting, played out across his parched, upthrust cliffscape, Hockney continually cues the audience, if only subliminally, to the day’s fateful passage.) Finally, with nightfall, Isolde arrives (it is her call from offstage that Tristan, by now entirely demented, greets by asking how he can possibly be hearing the light)—but she is too late: Tristan expires in her arms. And presently she herself, in an exaltation of grief and longing, literally sings herself to death with her celebrated Liebestod, her love-death, joining him at last.

This climax would be overwhelming in virtually any rendering at virtually any time, but during the winter of 1987, with the devastating scourge of AIDS rampaging through the gay and arts communities, Hockney’s Tristan must have had an impact all the more powerfully cathartic. By then Hockney himself had lost several of his closest friends to the plague, and several others—including many in the opening-night audience—were HIV-positive, some of those wracked by advanced stages of the illness. Hockney has occasionally been criticized over the years for not confronting the issue of AIDS head-on in his work, but as he has said, “I mean, you shouldn’t have to scrawl the word itself all over the wall in order to register a statement.” In any case, the charge itself is preposterous. How else are we to interpret the sudden upwelling of the motif of empty (vacated) rooms in his paintings around this time, or the gradual disappearance of variously lollygagging youths as a central motif in his work (the tender, loving gaze instead seeming to transfer over to the dachshund puppies he’d first acquired around this time)? But perhaps Hockney’s single most affecting confrontation with the AIDS scourge came here, in the immediate wake of Isolde’s dying swoon, as Wagner himself launches the orchestra into that final incomparable chord, the music rising, subsiding, rising, and subsiding again atop an incandescently sustained solitary oboe line: the apotheosis of love and unity beyond death. Perfectly rhyming his effect to the music, Hockney now turned his entire cliff pitch nighttime black, starkly silhouetting it against the engirdling sky, which suddenly swelled up blindingly bright, with rich blue stage lights cast upon the cobalt blue surround.

“The transcendental dawn,” Hockney now pronounced, having just re-created the effect that even inside the narrowed confines of his miniature model suggested an infinitely pearlescent expanse. “Because, of course, the thing is, Tristan’s ending isn’t the tragedy it might at first appear,” he continued. “That last chord: despite the bodies’ lying there littered all about the stage, the music somehow lifts you up and out of all that and onto another plane altogether, one of ineffable joy and a‹rmation, a kind of rapture.” Hockney paused, sighing, as if himself recalling the death-glutted context of those first performances. “When you suddenly find yourself surrounded by so much suffering,” he resumed, “you begin to think of death differently—I know I did: before I hadn’t really thought about death at all. It loses some of its terror, and it even begins to feel like a deliverance toward something else. I mean, I think for instance of Nathan and René”—two of his closest friends, both of whom attended the premiere and both of whom would be dead within two years—“death ended up joining them really, as they’d both fervently desired. That’s the higher possibility Wagner’s music holds out and that I too was trying to suggest, whiting out the backdrop sky like that.”

Hockney shook his head, sighing again. “But it’s really something: I can’t hear the low notes anymore. I mean I remember them, so I can sense myself filling in the blanks. But I can also feel all that sound just bleeding away.”

It occurred to me that perhaps that was going to be the subtext for this upcoming series of performances—the whiting-out, as it were, of an entire swath of Hockney’s own creative horizon: the bleeding away of sound, and of the possibility of any future such operatic collaborations on his part.

There was something deeply poignant and almost tragic about that prospect. And yet. . . For one thing I was reminded of something my grandfather, the composer Ernst Toch, used to say when people would provoke him with the hackneyed observation about how tragic it was that Mozart died so young. “For God’s sake,” he’d exclaim, “what more did you want from the man?” And indeed, what more—after the past twenty years and their entirely unexpected bounty of The Rake’s Progress and The Magic Flute, the French triple bill and the Stravinsky triple bill, Tristan and Turandot and Die Frau ohne Schatten—what more do we want from our man?

Beyond that, I don’t know, maybe I was still in thrall to the Tristanian ethos, but this didn’t seem an entirely desperate ending: there remained the distinctly happy possibility of transfiguration on the far side. I’d been struck by Hockney’s use of the phrase “whiting out” to describe his staging of the opera’s final moments—actually he’d used the phrase several times over the past few hours—when, of course, there was nothing the least bit white about that rapturously blue finale. Nonetheless, what in fact does await Hockney on the far side of these final upcoming performances is a virtually infinite expanse of empty white canvases. And as he’d also mentioned several times in passing, with an almost palpable eagerness and anticipation, “Enough of this already: it’s really time for me to be getting back to painting.”

A version of this piece originally appeared, under the title “The Colors of Silence,” in the Los Angeles magazine issue of February 1997.