A few years ago, David Hockney extracted a paragraph from the late astronomer Carl Sagan’s book Pale Blue Dot:

In some respects, science has far surpassed religion in delivering awe. How is it that hardly any major religion has looked at science and concluded, “This is better than we thought! The universe is much bigger than our prophets said—grander, more subtle, more elegant. God must be even greater than we dreamed”? Instead they say, “No, no, no! My god is a little god, and I want him to stay that way.” A religion, old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the universe as revealed by modern science might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe hardly tapped by conventional faiths. Sooner or later, such a religion will emerge.1

He photocopied it and embedded the text, beneath Sagan’s name, in a simple color drawing of a headstone on a rock-strewn plain, copies of which he proceeded to mail to friends. In the version I saw, he’d hand-scrawled, in the lower right-hand corner of the image, the simple injunction, “Love life!”

That drawing was very much on my mind, recently, as I flew out to the north of England to meet up with David in Bradford, his childhood hometown and the site of the Salts Mill, a mammoth old dilapidated Victorian textile mill complex entirely reclaimed over the past several years by his dear friend Jonathan Silver and the home now, among other things, of the 1853 Gallery, the world’s vastest emporium of Hockneyana. After a few hours touring the mill, David and I set out in his red roadster convertible—the top down, the footspace heater turned full up— through the rolling Yorkshire countryscape to the modest seaside resort of Bridlington, on the North Sea coast, where David keeps an attic studio in his sister’s house, a few doors away from the nursing home where his ninety-year-old mother now resides. Our conversation took place there.

LW: David, I’ve been thinking the past several days about that paragraph you embedded in your drawing of the Carl Sagan tombstone.

DH: Actually, when I made the drawing, Sagan was still alive—I don’t think I even knew he was in the process of dying of cancer at the time—and I’d intended the image more as a sort of tablet, a commandment. Though I can see how in retrospect the text might read as an epitaph.

LW: It’s interesting, I suppose, that I had that mistaken impression, but the larger point I’m getting at is still valid, because I’m struck by your response, over the past decade and a half or so, to what has truly been for you a death-permeated, death-haunted world. You have lost so many dear friends: your dealer Nathan and the countless others who’ve died of AIDS; Henry Geldzahler; and now Jonathan Silver. And your response, it seems to me, time and again, has been an almost defiant throwing in the face of death this love of life. Whether it is the flower paintings or the Tristan opera staging, the dog paintings, or now these landscapes. I mean, this refusal to be cowed and how, if anything, over and over again, you keep returning to magnificence and awe and—might the proper word be reverence?—as responses to all this devastation.

DH: Well, we all have a fear of death, of course. But, its opposite is surely the love of life. Which, I think, is a much greater force really. Or should be. I mean, Jonathan, a week before he died, said to me, “Paint those pictures, David. Keep on painting them. Life is a celebration, really.” I mean, here he was dying—he knew he was dying—and he understood that. And, ever since he died, actually, I’ve done nothing but work. Been just working away like mad.

LW: Can you talk about Jonathan a little?

DH: Jonathan was a fellow Bradford lad, though about twelve years younger than me. He first contacted me when he was editing an alternative magazine at my old high school to ask if I’d contribute a drawing. A brash, cheeky sort of thing to do—which I liked. And over the years I kept up friendly relations with him and presently his wife and their two lovely daughters. In 1987 he somehow acquired the abandoned old mill at Saltaire from the town of Bradford and set to reviving it—letting space to software companies, launching restaurants and bookstores along with that gallery devoted mainly to my work. He was wonderfully bright, cultivated, energetic, funny—we were in regular phone contact. And after Henry died in 1994, of a very rare form of pancreatic cancer, I found myself relying more and more on Jonathan for that sort of telephonic companionship.

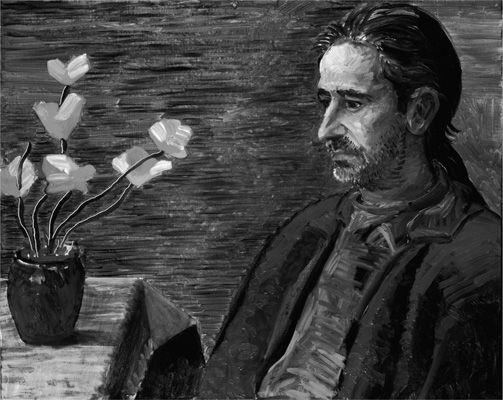

FIG 32 David Hockney, Jonathan Silver, 1996.

Then, exactly a year later—actually, I saw it first in my rendering of him [Fig. 32]—I could see it even before he told me, giving the drawings a second look later, after I’d finished them: Jonathan came down with cancer, too. And the very same kind as Henry’s! Incredibly bizarre. He fought it valiantly, even looked for a while like he had it beat: he ended up lasting two years. But by the summer of 1997, the cancer had come surging back.

LW: It must have been a terrible time.

DH : I was home in California, and everybody was saying, “Why don’t you go back? You’re too worried here. You’re going a bit mad.” Richard [Schmidt] said that. Gregory [Evans] said that. “We can see you’re always on the phone. Why don’t you go and see him?”

So I came back at the end of July. And I realized when I saw him—I could see he was deteriorating, he was very ill. I mean, you saw it in the face. After all, I’d seen this before. I realized, I can’t just fly back to L.A. What would I do there? So, I decided, well, I’ll stay here. And actually, I was quite comfortable here.

LW: Here in Bridlington.

DH: Yes, with my sister and her companion, Ken. And, I felt, well, if I’m going to stay here, I might as well get working. I have to do some work or something. I’d been here maybe three weeks, which is the longest I’d been here for a long time—

LW: Meaning, you were driving back and forth each day through East Yorkshire.

DH : To just east of York, actually—not quite as far as Bradford—where Jonathan and his family were now living. By August he wasn’t really going to the mill anymore.

LW: Maybe a forty-five-minute drive.

DH: Yes, and as you saw, quite attractive. I kept just going to his house. And one day, driving, I recalled how he’d always been saying to me, “Hey, why don’t you paint Yorkshire?”

LW: And why hadn’t you painted Yorkshire?

DH : Well, before, I’d simply never stayed long enough to even look at it that much. I’d come for a week and leave—not enough time to notice things, really.

Now, just before that, in June and July, back in America, I’d made two long driving trips from L.A. to Santa Fe and back, and I’d been contemplating doing some sort of big landscape of the West. Big spaces: that’s what was getting into my head. I was experiencing a growing claustrophobia or something—

LW: A fear of being in closed spaces, or more the love of being in open spaces?

DH: Yes. That’s it: the agoraphilia was stronger, the longing for big spaces.

LW: Could that be related to your progressive loss of hearing, the way the world of sound, for its part, has been closing in on you?

DH: It could be. It could be, but then I often think, you know, Why did I go to California all that time ago in the first place? At the time, I always said I’d gone because it was sexy, it was sunny. But Los Angeles is also the most spacey city in the world. You feel the most space. I was always attracted to its spaces as well. Always.

LW: And now East Yorkshire was turning out to be spacious in a similar way?

DH: Well, it was only after driving back and forth like that, through that actually very attractive space, where at times you could see a long way away— from the top of Garrowby Hill, you see the whole plain of York—that it began to occur to me how it does have some connection to the American West in that way.

LW: Can you describe for people who haven’t been here what East Yorkshire is like?

DH: Well, first of all, there are not many people who live here. Historically, it is beyond the Roman wall. The Romans built the town of York—they called it Eboracum—but this area was beyond that. And just to the south there is a wide river, the Humber, which they’ve only just recently built a first bridge over. So that no main road runs through this part of the country. You don’t come through Bridlington on your way to anywhere. You have to decide to come here. Which, come to think of it, may be one of the reasons this region has been so relatively little painted, historically.

But you have the Wolds, chalk hills with these tiny little valleys without rivers running through them. Strange: not caused by water or rivers. A bit like Normandy where Monet painted; that must be chalk there, too.

LW: A wonderful sense of scale. You have these little gullies that hardly deserve the name valley, they’re so tiny, but they have a sense of being big valleys.

DH: Right. I’ve been coming here for quite a long time, and it has hardly changed at all. But driving through the Wolds, virtually every day, I mean, I began really to look at them, you see. Also, it is agricultural country.

LW: I was going to say, in the context of the comparison with the American West, which is also quite underpopulated—but there one has the sense of nature in the raw, of a human confrontation with something alien, vast and other, whereas here we are speaking of a distinctly human space, a space inhabited and domesticated to the human scale.

DH: Well, husbandry is the word that comes to mind, if you think about it, a good medieval word. Biblical word from my youth. My mother’s quite religious, I was brought up a little religious, but then wandered off from it. But you do remember the language of the King James Bible.

LW: Husbandry, implying being husband to the land, in some intimate relation.

DH : Yes, and a changing one. Meaning the surface of the land is constantly changing, as I came to realize on those drives in my open car. I arrived at the end of July as they were just about to begin harvesting, so the corn was just turning to gold. The big machines were around, getting ready. They told me it rained all of June and July. The moment I came, it seemed to clear up. So this is August really, three weeks into August, and I’m going back and forth, watching, in a sense, the surface changing. I begin to notice how last week that was golden, now it has all these little dots on it from those machines, which were like pregnant insects laying eggs.

LW: The harvesting machines with their little rolls of hay.

DH : Yes, in the evening shadows. One field would be green and another would have these drops on it, another would have sheep, and the surface of the land was constantly changing. Also, I was driving over to see a friend who I was well aware then was in the process of dying. I didn’t say it, but deep down, that’s why I was staying.

LW: The sense of him near the end of his life and the bringing in of the harvest must have—

DH: Yes, the living aspect of the land, how they bring in the harvest: something dies, it grows up again. I began to see all that far more intensely than I would have if I’d just come for a weekend.

LW: And, on top of everything else, this person who was dying had specifically asked you to do portraits of the land.

DH: Well, Yorkshire has the biggest spaces of England, as I came to see, and I thought, maybe I can deal with those issues here. Also, I was pressed for time, in a sense, observing Jonathan’s decay. So, the first one I did was this sort of round trip . . .

LW: The one called North Yorkshire [Fig. 33].

DH: Yes, and of course it’s a trip, a hundred and fifty miles, actually, up there and back. But the first thing I drew was the outline, which, actually, happens to approximate the shape of Yorkshire on a map.

LW: It also reads to me as alternatively a head or a tree.2

FIG 33 David Hockney, North Yorkshire, 1997.

DH: Yes. Well, I began playing with such ideas, but I was aware that it was also a map.

LW: And there is no way to look at that painting without driving around inside it.

DH: Yes. LW: Your eyes go on a ride.

Now, the second one, The Road through Sledmere, I was painting at about the same time as The Road across the Wolds [Plates 17 and 18].

LW: And all these pictures, you were doing in this attic studio here?

DH: Right. Sledmere is a village that is around fifteen miles from here that, to my knowledge, has not changed one bit in fifty years. Those Edwardian red brick houses, with red paint on them, glorious in their redness those sunny days of late August, September. So one was getting marvelous greens, washed greens, the land changing, the very rich soil; and, in Sledmere I would drive up here, turn the corner, go back through here, around and off down there.

LW: I can say, as someone who has now been on this drive with you, that there is no place, no vantage, from which you could take this photograph. This is not intended as a reproduction of a single-point perspective.

DH: That was the point.

LW: But it does capture what it is like to drive through a place, as opposed to what it is to be frozen in place.

I notice, incidentally, how in all of these, there’s hardly any sky—I mean, in contrast to much of the rest of the great English landscape tradition. People like Constable and Turner. Or some of the Dutch painters, whose landscapes were often half-skyscapes.

DH: Yes, I suppose so, but when you’re driving you don’t really look at the sky, do you? You keep your eye on the road. And in fact, with some of these—The Road across the Wolds, for instance—I was consciously piling horizons one atop the next, such that when you were at one place in the painting, that’s the horizon you’d see, whereas a bit further along, you’d see this other horizon line. They’re fairly complicated paintings, actually.

So, anyway, I was painting away, and people in London would ask me, “When are you coming around? How long are you going to be staying up there?” And I’d say, “I’m painting some pictures of Yorkshire, actually.” And I remember someone said, “Aren’t they going to be a bit sad?” And I said, “No, I’m painting them for Jonathan. They’re going to show all the joy about the world I can. I’m going to take them over for him. Why on earth would I paint it gloomy, anyway?”

LW: I have to tell you, this whole series for me has the quality of a love song.

DH: Well . . .

LW: A quality, too, which may derive from the fact that alongside the death and last-things undercurrent you’ve evinced in these paintings, they were also constituting a sort of return to first things for you.

DH: Well, yes, as I told you on the drive over, I’ve really known this countryside quite intimately since the early fifties, when I came here to work during breaks from school—helping with the harvesting of corn. Wheat. Barley. I used to sack them for transport into Bridlington.

LW: And indeed there’s a certain T. S. Eliot “Little Gidding” from the Four Quartets quality to these paintings—“We shall not cease from our exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” I’m reminded, too, of Czeslaw Milosz’s recent return-tramps through Lithuania.

Can you talk a little about the use of reverse perspective in these paintings?

DH : As you know, the tyranny of vanishing-point perspective is something I’ve been obsessed about for years now—what it does to us—it’s gotten so as I can’t even watch television anymore because of the way the box focuses one’s gaze down that narrowing—

LW: Like a funnel.

DH: Yes, when all I want to do is just the opposite. Did I ever tell you the story about the time when I was in Milan, doing The Magic Flute at La Scala, and I took a drive to Zurich with Ian Falconer? And they’d just built this tunnel under the St. Gotthard Pass. The tunnel is about twenty-three kilometers long, of which about nineteen kilometers are a straight line. And, when we entered it, we were the only car entering. So all you saw was this rectangle ahead of you tapering relentlessly down to a single point in the middle, way up ahead. We were going on and on like this, and I said to Ian, “This is like living in one-point-perspective hell, this tunnel. Never have I experienced anything like this.” One found oneself longing so powerfully for the opposite, which at last one finally got, emerging from the tunnel.

LW: A sort of opening out.

DH: Exactly. Oh, I loved it. I love it. I love it, and I’ve never, ever forgotten that. In painting, reversing the perspective both brings the distant back up close to you, and also tends to undercut the illusion of being planted in a single space and time. It affords a sense of motion, of liveliness.

LW: So we’ve talked about the first three paintings. What did you work on next?

DH: Once I’d finished the first three, we rented a van and took them over to Jonathan—he was pleased, he immediately said, “Oh, they go back to your Grimm’s Fairy Tales etchings—the little Gothic towers.”

And, I thought, Well, I’ll paint Saltaire: the mill itself with the workers’ village all about it. This would be the earth altered even more: architecture, another big subject of mine, going way back, the apartment buildings in L.A., for instance, or the Mexican hotel courtyard painting from a while back. And, in this instance, I’d known the building since my childhood. I mean, I first probably walked down those roads when I was five years old—not more than three miles from our house.

So I drove over and walked around the streets again. I probably took a few little photographs, but this is not a view you could get—you can’t really find a view like this at all. And I said to Jonathan, “I’m going to paint Saltaire.” All he said to me was, “Show how big the mill is.” I said, “Yes, that’s the subject. How big, how great the mill is.”

I came back here and began working on it—put together two canvases. And I thought, “Well, I can play with these spaces now in an interesting way.” I’d take drawings and photos of the developing canvas over to Jonathan each day, and he immediately realized how if you hung this picture at the mill, people would understand what you were doing with the space.

So I was painting away, and I found it quite di‹cult, really. I mean, the mill itself, actually, is not a subject I normally would have dealt with. And on top of everything, I was working against the clock. Meaning, I knew he was getting worse and worse.

LW: Did you make it?

DH: Actually, it was finished about a week before he died. I think, maybe ten days before he died [Fig. 34]. I’d been showing him the snapshots as the painting developed, and actually he was quite talkative. But it was during that time that he told me not to worry so much about him, to get back to work, that life is—“You just paint those pictures, David. Don’t do anything else. Don’t bother with anything else now. You paint those pictures. Celebrate life.” I mean, he was fading away, in terrible … You know, the face begins to cave in. I’d seen it before. And I was in a turmoil, really. I mean, I was pleased I’d done these for him. But. . .

FIG 34 David Hockney, Salts Mill, Saltaire Yorks., 1997.

LW: Looking at the Saltaire painting now, do you see Jonathan’s death in it?

DH: No, I see his life in it, actually. I see his life.

LW: Strangely, a few minutes ago you described how you only first became aware of Jonathan’s illness—of the death in him—looking afterward at the drawings you’d been doing of him. And now here, in the painting you were doing as he was actually dying, what comes through is the opposite of his death.

DH: Because, why not? I mean, you don’t think of your friends now as they were when they were dying; you think of them as they were when they were alive. Always. That’s how I think of Henry. Jonathan.

So, but… he died just after. And I stayed a little bit. They had a very quiet funeral. And then I went back to L.A. It took a while to sink in, what happened. And I started on the next one.

LW: The double canvas: Double East Yorkshire [Plate 19].

DH: Which is more, as you see, the autumn. The plowing. The harvest is done.

LW: Your friend has been harvested.

DH: All’s been harvested. These were the colors of a much later summer.

LW: This strikes me more as a picture about rhythm than about death.

DH: Rhythms of the landscape around here, yes. And the way you see these patterns, and the plowing. In a way, I realized I hadn’t finished with Yorkshire, really.

LW: Or with Jonathan.

DH: No. And then I came back to Bradford: we did a memorial for Jonathan. We put the pictures up, these pictures, in a room at the mill, and we had an afternoon where I spoke, a few people spoke about him. From there I went on to Cologne, where they were preparing a show, came back to L.A., continued finishing the harvest painting, and then went on to . . .

LW: To Garrowby Hill.

DH: Garrowby Hill, yes, which I’d wanted to do. It was in me. I probably painted it in three weeks, though, of course, I’d been planning it for much, much longer [Plate 20].

LW: Can you talk about it a little bit because to my mind, it’s the culmination of the whole series—the one that really brings things all together.

DH: Well, it was the very last one of the Yorkshire pictures, and the one that anticipates the big vistas up ahead.

LW: First of all, can you describe—where was this?

DH : Well, Garrowby Hill is the hill that—York is a city nestled in a great big plain. The Vale of York. The rivers from West Yorkshire meet in York and go on out on the Humber. It is a very flat area. And Garrowby Hill, on the eastern edge of the vale, is the hill where the chalk wolds rise up. And you go from, probably, sea level, to about eight hundred feet.

LW: So, each morning coming over from Bridlington, this would have been your view.

DH: I must have driven up and down that hill—probably sixty times in the previous few months. So it was very strong for me. A very powerful feeling. On clear days, you could probably see fifty, sixty miles, which is a long way for England. And there, on the horizon, you could make out the cathedral, York Minster—twelfth century, huge building.

LW: But the main thing from Garrowby Hill is the sense of scale.

DH: And it also imparts this marvelous feeling, how you’re about to take off and fly. A momentary sense of soaring.

LW: Can I try a few associations that I get from the picture on you? First of all, there is no question in this picture that you’re driving. You are not just standing there, you are driving into this vista. Not only are you driving, but somehow it is clear—somehow you have conveyed this—you have just come over the hill. In fact, your back wheels are still on the other side of the hill, and the front wheels are only just beginning to start down. And I in turn have two sets of associations to that sense of dynamic. One is to what it was for you to be coming over the hill of this terrible thing you’d just been going through. Coming out the other side, as it were, onto the wide expanse of life remaining for you and the work remaining for you, all the fields remaining for you to go after. But also there’s a kind of magisterial quality of what it is or was for Jonathan—

DH: Jonathan.

LW: For him to have come over the hill of his life, and of his final illness, out into this kind of openness, which is where I come back to the Carl Sagan quote. Or phrased differently, maybe: this whole painting seems about overcoming. You are coming over the hill. You are overcoming.

DH: That’s very good. Yeah. Overcoming.

LW: Which is why this picture feels so much to me like the culmination of that whole body of work.

DH : And it was painted in California without any references, really, at all. And most of those fields keep opening out, you see.

LW: Again: that reverse perspective.

DH: Always opening, as if you were coming out of this tunnel. Which, in a way, I suppose, I was.

LW: Let’s gradually go from talking about painting things that generally had not been painted before to painting things that people said were unpaintable. You were telling me the story about an ad for the Santa Fe Railroad.

DH: Well, I went to the Thomas Moran show in Washington, D.C., last December, in the middle of all this, just before I began moving toward my Grand Canyon paintings, and in the catalogue they featured an early ad for the Santa Fe Railroad, which characterized the Grand Canyon as “the despair of the painter”—meaning, it was too di‹cult to paint. And I must say, I’d always thought the Grand Canyon was unphotographable, in a sense, as well—by any conventional means, at any rate. In fact, generally, I’ve long felt that the one aspect of photography that seems to have let us down is, actually, landscape.

LW: How so?

DH: Photography seems to be rather good at portraiture, or can be. But, it can’t tell you about space, which is the essence of landscape. For me anyway. Even Ansel Adams can’t quite prepare you for what Yosemite looks like when you go through that tunnel and you come out the other side.

LW: Is that why, back in 1982, you headed out to the Grand Canyon almost immediately as you moved from your Polaroid collages to working with a more ordinary camera?

DH: Exactly. I wanted to try to photograph the unphotographable. Which is to say, space. I mean, there is no question—for me, anyway—that the thrill of standing on that rim of the Grand Canyon is spatial. It is the biggest space you can look out over that has an edge. I mean, of course space is bigger if you turn your head and look up, but that space is incomprehensible to us, really.

LW: And indeed it seems to me that each time you’re on the verge of some sort of breakthrough, pictorially, you return to the Grand Canyon to see whether you can lick your chops on that.

DH: Well, I must admit I’m always thrilled by it. I mean people go to look into it, don’t they? Very few actually go down into it. And actually, you can peer into it for an awful long time. And you look all over. I mean, it is the one place, I think, where you become very aware of how you move your head, your eyes, everything.

LW: In a way what you’re saying is, it is the one place where everybody actually peers at the world the way you are suggesting one should peer at the world all the time.

DH: Well, the way we do look at the world all the time.

LW: But you become aware of doing so at the Grand Canyon?

DH: You become very aware of it there. I think so.

LW: Actually it was delving once again into those photocollages of the Grand Canyon from the mideighties that proved the immediate occasion for the current series of paintings, wasn’t it?

DH: Well, the Ludwig Museum in Cologne was preparing a retrospective of my photographs around this time, and I’d gone over to look at the space, and there was going to be this very large room with a large wall at the end of it. And this afforded me the opportunity to try something I’d wanted to do back in the mideighties—to blow up one of those photocollages into a wall-size mural—something that would have been prohibitively expensive to do back then, but in the meantime, what with laser reproduction, had become entirely feasible. The Grand Canyon seemed the ideal subject for such an exercise—the right scale—and I began reviewing some of those collages, eventually choosing one I’d photographed in 1982 but had actually only put together in 1986, at the time of the ICP retrospective in New York.

LW: When was this?

DH: Well, I was now back in L.A. as we were blowing up the negatives. This would have been January, while I was starting on Garrowby Hill. And then I went back out to Cologne to supervise the installation of the wall mural, and it turned out well enough—I mean, people liked it—but what I noticed was how the image did not read from a great distance. It seemed to lose its presence, its impact, as you stepped back [Plate 21].

LW: Why, do you suppose?

DH : Well, for starters, photographic ink, photographic printing, any kind of printing, is not like paint. This is one of the lessons I took from the Vermeer show: the colors! The vibrancy of the colors after all these years. I spent hours in those rooms in The Hague, just studying how he did it, how he made those images glow like that. Just technically—the layering, the building-up of thin layers of colors one atop the next, the foreplanning. I joked that Vermeer’s colors will last a lot longer than MGM’s, but it’s true. And I applied those lessons to the flower paintings I did immediately thereafter—people would say, “What do flowers have to do with Vermeer?” and I’d say, “I’m not talking about subject matter”—and then in the Yorkshire landscapes as well. And the photocollage mural in Cologne, as impressive as it was, couldn’t hold a candle to that kind of presence. I turned to Richard and said, “I should paint the Grand Canyon; I’m going to have to paint the Grand Canyon now.”

I decided to do a large wall piece across a grid of sixty small canvases (the same number as there were individual snaps in the photocollage)—in part because it would be more manageable, working in the studio, but also because, as with the photocollages, such a cubist method, as it were, would allow sixty separate vantages, sixty separate vanishing points; it would undermine the one-point perspective and help entice the viewer’s eyes to rove about.

LW: Just like at the canyon itself. How would that have differed from, say, Thomas Moran’s approach?

DH: I should say, incidentally, that I thought that that was a marvelous exhibition, very enjoyable. Moran was actually an Englishman himself, born exactly one hundred years before me not forty miles away from Bradford. And he, too, obviously, developed a taste for the American West. He went along on Powell’s 1873 expedition into the canyon, but almost under a government commission, with the intention, the assignment, of conveying information—about topography, geology, and so forth—as accurately as possible. As I say, that’s not my interest. I’m trying to convey the experience of space.

LW: Moran also seemed fascinated by atmospherics, by weather and microclimates. There’s no sense of haze in your version.

DH: And I didn’t want any. I didn’t want to use any atmospheric color—the colors on those canvases are very vivid, pure—which in turn was one of the reasons why, even when you were looking at the various studies, and then the developing canvas, from the far side of the studio, it was still as if you were at the very edge of the canyon. In fact, I realized that the further back you got, the stronger the image read [Plate 22].

It was reminiscent of something I’d learned doing Tristan.

LW: I was going to say, this image itself is reminiscent of your staging of Tristan: the ship’s prow, the cliffscape. And perhaps that is not surprising, since the photocollage it’s based on was put together in 1986, only a year before you first designed those Tristan sets.

DH: Well, onstage, the thing is, if you put a real tree there, if you’re sitting in the front row, you’ll feel near to it, while if you’re sitting in the back row, you’ll feel far away. Whereas, for instance, the wiggly lines I painted in on the mast of the ship in Tristan made it such that it didn’t really matter where you sat: you felt you were on the ship even if you were in the back row. And I’ve noticed how all the paintings I’ve done since 1988 share that feature: they read across the room. Especially this Grand Canyon.

LW: Making distance intimate. Indeed, I noted, when I went to see this recent Bigger Grand Canyon of yours during its premiere showing in Washington—in fact, right next door to where the Morans are usually hanging at the Smithsonian— everybody seemed to be pushing back, as far away as possible: there was a whole group pressing themselves against the far wall. By no means in revulsion. I was assuming this was because they were trying to get it all in their visual field at once.

DH: In part, perhaps. But it’s also the case that the more the viewer pushes back, the more the image pulls him in. It becomes clearer and clearer, stronger and stronger.

LW: The way the sky works seems important in that regard here as well. Again, you have virtually no sky presented, just a thin sliver at the top, and, yet, there’s a huge feeling of the sky above you.

DH: Well, because everything above the painting can be the sky.

LW: The blank of the wall. . .

DH: … can read as an infinite sky.

LW: Whereas if the sky went halfway down the picture, as it does, say, in a Moran, that would be all the sky there is.

DH: That is it. Exactly.

LW: This way, the white of the wall above the canvas, and specifically above the point on the canvas representing the farthest horizon from you, can read as sky, going up and up, along the ceiling and then, over the top, even behind you—while the bottom of the image, the rim of the canyon, likewise bleeds into the lower wall and then the floor and on under you. The two vectors, as it were, meeting behind you and drawing you in.

DH : And all the more tautly the further back you stand. That’s why you feel sucked in, as if there’s no gap between you and it.

LW: You were telling me a story about Ed Ruscha . . .

DH: Yeah, I met him at a party one evening as I was working on the big painting, and I was leaving early. I said, “Well, I’m going home. I go to bed early. I get up very early. I’m doing this large painting of the Grand Canyon.” And, he said, “Well, in miniature, of course.” Which I thought was very witty. For, of course, whatever size we do it, it will be a miniature.

LW: To what extent as you were painting this painting do you suppose Jonathan’s deathbed injunction—that you should go out and celebrate life—was still reverberating in your mind?

DH: Well, actually, yes. Surely it was, really.

LW: The reason I ask is that, again, what is interesting in the Yorkshire paintings is their evocation of a very lived-in geography: the farms, the haystacks, the sense of human scale and habitation. Whereas the Grand Canyon, par excellence, is almost inhuman in its vastness: space and rock and little else. But at the same time, what is celebrated in your painting is the human capacity for perception. And, and the wonder of being alive before that kind of awe.

DH : A friend of mine looked at it and said he thought he was on the way to Heaven, as he put it. A very nice thing to say, really. My sister thinks space is God, and I like that.

LW: Which brings us back to Carl Sagan’s insistence that we not be satisfied with puny Gods.

DH: Right, because his comment is actually about big space, isn’t it?—how God must be even greater than we dreamed of. Much bigger. The universe, bigger. Grander. Vaster. More spacious. I thought that was marvelous.

This text was originally composed for the catalogue to the Looking at Landscape/Being in Landscape exhibit of Hockney’s East Yorkshire and Grand Canyon paintings at the LA Louver Gallery in September 1998.