Heads up! Watch out! Looks like Hockney’s on another one of his perceptual-conceptual tears.

Or so I quickly came to realize several weeks back when I happened to be in Los Angeles and, as I usually do on such occasions, gave him a call to see how things were going. “Where are you?” Hockney demanded to know once, with no small di‹culty in hearing, he’d finally managed to ascertain who I was. “Can you get up here right away? There’s something I have to show you!”

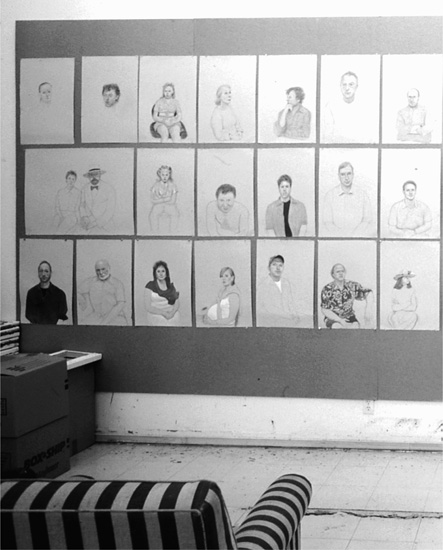

Meeting me at the front door of his colorful home a few hours later, Hockney didn’t even bother inviting me in for our usual tea, instead squiring me immediately up to the hillside studio, where the inside wall to the left of the entry was covered over with dozens of recent portraits of friends—or rather, on second glance, photocopied blowups of the lovingly rendered drawings whose originals had likewise been ranged along the perpendicular wall facing the studio entry (Fig. 35). Confronting such a remarkable array, I immediately thought of the death of Hockney’s mother, at age ninety-eight, earlier in the year. As one of Hockney’s studio assistants had commented to me in the wake of a similar eruption of the artist’s impulse toward portraiture a few years back, immediately following the death of his beloved friend Henry Geldzahler, David tends to respond to such desperate losses by gathering his surviving friends yet closer around him in a sort of defiant inventory of the life that remains.

Hockney allowed me a few moments to admire the portrait walls, but rather quickly (uncharacteristically so) drew me away toward the wide worktable in the middle of the studio, which was covered over with art books, reference manuals, bulging folders, and hastily scribbled memos. One might have been excused for imagining Hockney to be gearing up for a full-frontal assault on the entire history of the Western painterly tradition; and, as it turned out, one would not have been far wrong.

FIG 35 Camera lucida drawings in David Hockney’s Los Angeles studio, September 10, 1999.

“The past year, as you know, was an incredible one for art shows,” Hockney now launched out. “The Pollock in New York, the Monet in London, and the Ingres, also, initially, in London. I spent hours at each, and each seemed to leave me more exhilarated than the one before. Especially the Ingres, which I went back to three times—the paintings, but, in particular, the drawings. Now, for someone like me, trained in the conventional Carracci tradition—you know, plumb line, the extended thumb, gauging relative proportions, and so forth—those pencil portraits of Ingres’s were mind-boggling. For one thing, their size—how small they turn out to be, when you get to see them in person. The images are seldom more than twelve by eight inches, incredibly detailed and incredibly assured. If you draw at all, you know that’s very rare and not at all easy. I bought the catalogue, brought it back here to L.A., studied it some more, read every word, blew up some of the drawings on the copier over there, and one morning, studying the blowups, I found myself thinking, Wait, I’ve seen that line before. Where have I seen that line? And suddenly I realized, That’s Andy Warhol’s line.”

Hockney cited Studio Still-Lifes, a show of Warhol’s at Paul Kasmin’s gallery, in New York, the year before last. “Because Andy’s is indeed the same kind of line: clean, fast, completely assured. Now, in Andy’s case we know he was using a slide projector—Kasmin even had the original photos from which Andy had traced his images.” Hockney reached for the Kasmin catalogue, opened the slim volume to a page featuring Warhol’s 1975 arrangement of a bowl, a can opener, and a handheld mixer (Fig. 36), and then opened his well-thumbed Ingres volume to the stunning 1816 portrait of Lady William Bentinck (Fig. 37).

“Look at that,” Hockney said, “and now look at this, especially the clothes, the fall of the draped cloak, the ru›e around the neck, the gathered sleeve, and then her expression, its palpable freshness: the speed of the line, its boldness, its absolute confidence, no awkwardness, no hesitancy. Of course, Ingres wasn’t using a slide projector, but he might well have been using a camera, a refracting instrument of some sort.”

Hockney reminded me that cameras and lenses long predated the invention of chemically fixed photography. For that matter, the things that happen to light as it passes through a pinhole are natural phenomena—“as omnipresent and wondrous as rainbows,” Hockney said, and went on, “People have marveled over them literally for millennia, tinkering with ways to exploit the effects. And the more I looked at Ingres’s drawings, the more convinced I became, on the basis of the optical evidence of the images themselves, that Ingres had to be using some sort of device based on those effects.”

Hockney recalled how when he was in art school he’d been shown a camera lucida, a device invented in 1807. So now he sent his assistant down to an art supply shop to see if he could find one. “Turns out they’re relatively rare nowadays and quite expensive: the one he found cost over two thousand dollars,” Hockney said. “Anyway, I set up a little corner and—come here, I’ll show you.”

FIG 36 Andy Warhol, Still Life, 1975.

FIG 37 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Lady William Henry Cavendish Bentinck, née Lady Mary Acheson, 1816.

Alongside the drawings wall, Hockney had erected an alcove, cordoned off with screens and curtains. This cozy little nook (I’ve often thought of Hockney, like Auden before him, as a sort of phenomenologist of the cozy) contained a comfortable chair propped before a flat drawing table, on which Hockney had installed his camera lucida—a tiny prism (barely wider than an eyeball) suspended, as if free-floating, at the end of a flexible metal rod. He showed me how when you looked down through the prism, the image of whatever happened to be before you seemed to be transposed onto the tabletop—or onto any blank sheet of paper that you might put there. The effect was illusory: no image was actually being cast on the page, as with a slide projector. But one could deploy the illusion to help capture a likeness (Fig. 38).

“Sit there,” Hockney commanded, and then spent a few moments adjusting my pose. “Perfect,” he said. “Stay like that.” He fetched a sheet of Arches paper and a canister of sharpened pencils, laid the page beneath the prism, and set to work.

The first part of the session lasted about an hour, but Hockney used the camera lucida itself for only two or three minutes—quickly and, yes, with startling assuredness, sketching out the tangle of my hands, legs, and sleeves, and then, turning to my face, laying in the general shape of my head. Muttering, “This is the crucial part,” he posited, with the faintest of pencil stabs, the coordinates of my pupils, the corners of my eyes, my nostrils, the lay of my glasses over my ears, the edges of my mouth. After that, he reverted to a more standard posture, gazing past the hovering prism, as if it weren’t even there, and probing my face and then the page, back and forth. His own face was becoming increasingly scrunched up with concentration, so much so that at one point his earpiece began to screech (he plucked it out and set it aside); his tongue, animate, prehensile, lolled and darted from one side of his half-opened mouth to the other in evident syncopation with his drawing hand (it was as if he were thinking with his tongue). Only once or twice thereafter did he bother to look through the prism, for minor adjustments.

FIG 38 David Hockney drawing with a camera lucida, 1999.

At length, we took a break, and Hockney reinserted his earpiece. The gist of the image was already well in hand. “Especially the mouth,” Hockney said, tapping the page. “It’s always the hardest to get right when you’re just eyeballing it. Wasn’t it Sargent who said, ‘A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth’? And a smile is hardest of all: it’s not just the mouth but, rather, the precise fleeting relation of the mouth and the eyes, the crinkles around the eyes. I used to struggle for hours—days!—to get a proper likeness, revising and revising so as to transcend the drawing’s inherent awkwardness, and, even so, if you look back, say, at those meticulously realistic drawings of mine from the early seventies, you’ll notice how the sitters are hardly ever smiling: they’re stiff, poised, still—posed.”

He reached once more for the Ingres catalogue. “Whereas here, look,” he said, turning the page. “And this one here, see: absolutely no awkwardness. Not always; not every time. In some of the studies, especially early ones, he’s laid in a traditional grid, and you can see his hand groping. But then you get another of those amazing pencil portraits he was doing in Rome, as a kind of sideline—visiting English gentry on their grand tours, people he was often meeting for the first time. He just dashes the images off, usually in a single sitting, with complete authority.”

Hockney rifled among some of the other books and images spread about his table. “The thing is, once I started seeing it in Ingres, I began to notice lens- or mirror-based imagery, optically rendered imagery in all sorts of other places, including before Ingres, and in fact well before. Hundreds of years before.

FIG 39 Albrecht Dijrer, Artist Drawing a Lute, 1525.

FIG 40 Caravaggio, Young Boy Singing and Playing the Lute, 1595.

“Look here,” he said, grabbing a photocopied image. “Most painters, most artists, are highly secretive about their methods. One of the few who were willing to divulge their secrets was Dürer, in the early sixteenth century. In this woodcut, he’s showing how you drew a lute in perspective without, or maybe before the introduction of, lenses. Very complicated, very cumbersome. Takes two guys, an adjustable sightline, a slidable perpendicular grid, a page mounted on a hinged side panel that keeps getting swung into and out of position to note the precise spot where the moving sightline crosses the imaginary picture plane . . . Must have taken hours. That’s—what?—that’s 1525. And now look at this.” Hockney pulled out a reproduction of Caravaggio’s Young Boy Singing and Playing the Lute. “This is— what?—1595. Not only has Caravaggio rendered a lute in complex perspective, perfectly and seemingly effortlessly, with absolute authority, but he’s thrown in a violin lying there on the table for good measure” (Figs. 39 and 40).

Back to Dürer, 1525. Hockney showed me another woodcut, this one portraying an artist using an intervening gridded glass plane to block out a portrait; the artist has to keep his eye steady, peering through an eyehole at the tip of a raised stick, and his subject is forbidden to move. “No wonder,” Hockney was saying, “that when you paint like this you end up with faces like this.” He showed me Christ and the Fallen Woman, by Cranach the Younger, a rendering from about the same period: stiff, impassive faces, mouths grimly shut, expressions stilled.

“Whereas just a few years later you get faces like these.” Hockney began flipping through a nearby Caravaggio catalogue. Almost all the faces were vividly alive, openmouthed (“You try keeping your mouth open like that for more than a few moments, as one would have had to, using Dürer’s gridded-glass method”), and characterized above all by fleeting, evanescent expressions—expressions, as Hockney put it, “captured on the fly.”

He went on, “Notice the constant sense of assurance. And with no drawings, no sketches! There are no preparatory studies with Caravaggio. At any rate, none have survived. Or, for that matter, with Velázquez. Or Vermeer. Or Hals. Or Chardin. Hardly any.” Hockney rustled through one reproduction after another. “Suddenly, they all seem to be able to render the image, just like that, onto the canvas itself. And it’s not just the great masters.” He showed me Dirck van Baburen’s Concert, of 1623: a lute, a violin, one player grinning antically, another with his mouth open. Seemingly effortless.

Of course, the keyword there was “seemingly,” for as Hockney went on to insist, “Optics don’t make paintings; artists do. The lens can’t draw a line, only the hand can do that, the artist’s hand and eye in coordination with his heart. And, in any case, such optical devices are quite hard to use. You have to be a good draftsman to be able to take advantage of them at all. It took me a good several months to learn how to use that camera lucida. You look at somebody like Ingres, and it would be absurd to think that such an insight about his method undercuts the sheer marvel of what he achieves. Nobody can do it as well as he can—the subtlety of characterization, the inner life of the drawings—and the more I study him, my admiration just goes up and up and up. This whole insight about optical aids doesn’t diminish anything; it merely suggests a different story, a more accurate one, perhaps—certainly a more interesting one.”

With growing excitement, Hockney proceeded to lay out the broad contours of that story as he was beginning to understand it. Coming out of the Middle Ages, most painting, most rendering, he suggested, was a matter of “eyeballing,” of “awkward, groping approximation,” but the early Renaissance, especially in Italy, saw the rise of various mathematical systems of perspective and proportion—the transition, say, from Giotto (Fig. 41) to Piero della Francesca and Uccello, and then on through the glories of the High Renaissance, to Michelangelo and Titian. These systems of perspective were grounded in ever more elaborate intellectual superstructures, a virtual science of vision: tapering grids projected onto empty space, and then filled, according to rigorous rules, with the artist’s idealized renditions of reality.

Hockney was becoming convinced, however, that during the sixteenth century in different places and at different rates, an alternative way of proceeding started to emerge—one based on mirrors and lenses. It had been widely known since antiquity (Aristotle and Euclid both make much of the fact) that when light passes through a small hole into a darkened enclosure, a vivid if inverted image of the external world may appear on the far wall. The effect was much discussed, in tones of hushed and pious marvel, during the Middle Ages and went on to become a central motif—the metaphor, that is, of the eye itself, and, for that matter, the mind, as a room receiving, through a pinhole and onto a blank wall, sense impressions from the outside world—in the epistemologies of thinkers ranging from Kepler and Newton through Descartes, Leibniz, Locke, and beyond. With the passage of time, the effect was deployed in a series of ever more sophisticated boxes—camera obscuras (literally, “darkened rooms”)—with lenses to sharpen the projection and mirrors to reverse the inversion. Inevitably, such boxes drew the attention of artists; by the middle of the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth, the devices were in common evidence. Canaletto, for example, used them in his depictions of Venice.

FIG 41 Giotto di Bondone, Marriage at Cana (detail), 1303-6.

But Hockney was increasingly coming to suspect that versions of lens-and-mirror technology (perhaps without the rigid confines of the camera obscura itself ) were being used by artists long before that—initially, perhaps, in northern Europe (with Van Eyck and subsequently the Dutch landscape artists), but rather quickly spreading into northern Italy (and especially Caravaggio’s Lombardy) as well.

The transition to lens-assisted artistic production was not without its controversies. Caravaggio, for instance, was regularly attacked by his more conventionally perspectival academic contemporaries, but, as Hockney now pointed out, “the attacks themselves were quite revealing.” He reached for Howard Hibbard’s 1983 monograph on the artist, which includes a generous sampling of such criticism. For instance, he cited Giovanni Pietro Bellori’s slamming of Caravaggio for making “no attempt to improve on the creations of nature” and for lacking “invenzione, decorum, disegno or any knowledge of the science of painting.” Bellori speaks of Caravaggio’s need for models, “without which he did not know how to paint,” and notes how older painters accused him of being able to paint only in cellars—which is to say, dark spaces—“with a single source of light and on one plane without any diminution.” Nonetheless, Bellori goes on, “many artists were taken by his style and gladly embraced it, since without any kind of effort it opened the way to easy copying, imitating common forms lacking beauty.”

“Well, maybe not that easy,” Hockney concluded, putting the book aside. “I mean, few artists could do it as well as Caravaggio. But, still, it’s clear from attacks like these that they must be talking about optical devices of some sort—devices whose use is further confirmed by the evidence of the paintings themselves. I mean, for instance, compare the mathematical foreshortening involved in one of the slain battle figures in a picture of Uccello’s with the uncanny rendering of the Apostle Peter‘s outstretched arms in Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, with the near and far hands almost the same size—precisely the effect you’d get, incidentally, with certain kinds of telephoto lenses” (Figs. 42 and 43).

These optical techniques were increasingly dominant in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and became virtually ubiquitous during the first half of the nineteenth century, at which point, according to Hockney, “Suddenly something happens. And that, of course, is the invention of photography—or, to be more precise, the invention of various methods for chemically fixing the sort of lens-cast image that up till then had required the interposition of a human hand.”

Hockney pointed out that photography grew directly out of the camera lucida. Rummaging around in his pile, he read from William Henry Fox Talbot’s account of how, in 1833, by the shores of Lake Como, he’d been attempting to sketch with a camera lucida, though “with the smallest possible amount of success.” For, Talbot went on, “when the eye was removed from the prism—in which all looked beautiful—I found that the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.... The idea occurred to me . . . how charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed upon the paper!” By 1835 Talbot was experimenting with papers soaked in silver chloride, and by 1839 he was able to publicize his method; by 1841 he was using negatives to make multiple positives, a marked improvement on Louis Daguerre’s method, developed around the same time, which could produce only a single image.

On first encountering a daguerreotype, Ingres’s great rival, Paul Delaroche, declared, “From today, painting is dead.” For his own part, as Hockney points out, Ingres himself increasingly turned to photos rather than the camera lucida in the years prior to his death in 1867. “His late self-portraits all have the tonality of photographs,” he elaborated, turning once more to the catalogue. “Compare the forehead from his portrait of Monsieur Bertin, of 1834, here, with the forehead in that late self-portrait and you can see the effect on painting of the daguerreotype.”

But it wasn’t so much that photography killed painting, Hockney now went on to argue (“I mean, obviously not!”), as that it provoked a decisive rupture in the blending of painting and the sort of lens-based way of seeing that had dominated it for more than three hundred years. “By 1870, the photograph had pretty much established itself as a cheap form of portraiture, and artists, for their part, started to fall away,” he said. “Cézanne, for instance, starts to look at the apples before him with both eyes, opening one and then the other, and painting his doubts [Fig. 44]. Awkwardness returns to European painting, for the first time, really, since Giotto. Surely this is part of why the artists of Europe suddenly start turning toward Japan, and China, where the lens-based methodologies had never held sway.

FIG 42 Paolo Uccello, The Battle of San Romano, ca 1455.

FIG 43 Caravaggio, The Supper at Emmaus, 1601.

FIG 44 Paul Cézanne, Apples and Biscuits, ca 1880.

“Soon cubism arises and, in this context, can be seen as an ongoing critique of monocular photography and, by extension, I suppose, of the entire lens-based tradition that preceded it. Painting would now endeavor to capture all the things a photograph or a single-lensed vantage could not: for example, time, duration, multiple vantages, the sense of subjectively lived reality. As the years passed, that rupture between painting and lens-based opticality widened, though at first, I’m convinced, it was a choice. Cézanne and his contemporaries knew about the various lens-based devices and chose not to use them. But within a generation or two the knowledge had been lost. And eventually you get to a generation like mine, going to school and looking back at Caravaggio and Velázquez and Ingres, and we honestly can’t imagine how they were able to do it. The question itself doesn’t even occur to us. They loom there like giants, preternaturally gifted, demigods, almost another species.”

FIG 45 David Hockney, Lawrence Weschler, Los Angeles, 20th September 1999.

I was reminded of the way the peasants, deep in the Middle Ages, had gazed upon such antique relics as the Pont du Gard, the soaring Roman aqueduct outside Nîmes, stumped as to how fellow humans could have built such things, and convinced that a species of giant must once have strode the earth.

“Well, maybe we should finish that portrait,” Hockney now said, smiling, as he straightened his books and pages. He escorted me back to the alcove, pulled out his hearing aids, and set to work. (It suddenly occurred to me that this surge of insights regarding the history of optical devices was flooding over an artist and thinker who happened to be finding himself more and more reliant on auditory ones—

sound lenses, as it were.) Over the next forty-five minutes, Hockney peered through his camera lucida another three or four times. The rest was steady gazing: my face and the sheet before him.

The likeness, once he’d concluded, was indeed striking, and the speed with which he’d rendered it even more so (Fig. 45). Oddest of all, though, was a strange distortion: my front arm seemed to bulge, as if in a convex mirror—much like that in Parmigianino’s famous Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (from 1524).

“Precisely,” Hockney said. “But look at the size of the image”—about twenty inches high. “If an artist wanted to avoid such distortions, he’d have had to have his subject stand further back, and the resultant image, in turn, would have been much smaller. Which, for that matter, is probably why those Ingres drawings are so small.”

I’d noticed John Walsh’s visage up on Hockney’s portrait wall, not terribly well rendered (the face was still fairly stiff) but unmistakable nonetheless. I knew that Walsh, the erudite director over at the Getty Museum, had been a longtime admirer of Hockney’s and had even helped to secure what was arguably the finest of Hockney’s photocollages from back in the eighties—Pearblossom Hwy.—for the Getty’s own collections. I figured I’d give him a call to see what he made of all this. (In another guise, Walsh is also a vastly knowledgeable art historian, especially steeped in Dutch art of the seventeenth century.)

“Well, I mean, it’s quite remarkable, isn’t it?” Walsh said, laughing, when I reached him by phone. “The sheer intensity of David’s passion these days. David will often take a sound general observation—and not infrequently, like this, a surprising one, one that’s long gone unnoticed—and then push and push it, way, way out to the very limit and beyond. Which is fine: it’s what makes him an artist, that divine confidence of his. But in this latest discourse, marvelously suggestive as several of his notions are, I fear that David may well find himself sailing against the wind. For before the seventeenth century, where’s the evidence? Where’s the testimony of sitters or other contemporaries, or the treatises of the artists themselves? We have vast inventories, often compiled for inheritance purposes at the time of artists’ deaths, every single brush accounted for—and where are all the lenses and other devices you’d expect to find listed, if David were right? It’s pretty dicey.”

Back in New York, I looked up Gary Tinterow, a senior curator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum and one of the principal organizers of the Ingres show, which had been at the Met last fall. He had been through the exhibit several times with Hockney, and had even slotted the artist for an appearance at an all-day Ingres symposium scheduled for a few weeks hence.

We met in the galleries, and I found him a bit more receptive than Walsh. “Hockney’s insights are potentially very important,” Tinterow told me, “not only with regard to Ingres but maybe even more so with regard to some of the others, especially those painters for whom, as he notes, we don’t have any preliminary sketches. But it will all depend on fact finding: our work as historians is now cut out for us, to find corroborating evidence. I mean, I think one can already say that Ingres’s drawing style does undergo a noticeable shift after 1807, the year the camera lucida would have become available to him; and when I’m with David I can in fact see what he means by the Andy Warhol line, especially as it courses from one distinct garment, say, over onto another and then back again, seemingly oblivious of the separate volumes. Other times, though, by myself, I’m not so sure; that kind of skating over distinct volumes doesn’t seem as evident to me.

“And, for instance, take this image here”—we walked over to one of the earliest pictures in the show, dated before 1806. “David would doubtless speak of its elongated foreshortening, how one is given to see more than one could ordinarily take in in a single glance—this kind of scooped-out concavity, from which David would infer that Ingres had to be looking through some kind of lens. Sounds great, sounds plausible, but we just don’t know it to be the case. And the very same qualities, for that matter, could result from other factors. Perhaps Ingres is consciously quoting from earlier sources, and that’s why you get these effects. Then again, maybe those earlier sources—Bronzino, Jacques-Louis David—were using optical devices of their own. As for the relative smallness of the drawings, perhaps, as David suggests, they result from Ingres’s use of a camera lucida. On the other hand, Ingres’s father was also a painter and, in particular, a miniaturist, and maybe it has something to do with that. Then again, as a miniaturist, maybe his father was likewise using lenses. It would be nice if we could find an account from one of Ingres’s sitters—and there are many who left such accounts, who mention his easels and brushes and canvases—a sitter who described Ingres’s use of such optical devices. On the other hand, who’s to say we won’t yet come upon just such an account, especially now that we know what to look for?”

Such comments were typical of the hesitations raised by several (though not all) of the art historians I spoke with in the ensuing weeks—and several were far more bluntly dubious. Hockney was unfazed. “For one thing,” he told me when I telephoned, “the paintings themselves are the evidence, if you know how to look at them—if you look at them, that is, as an artist would look at them. Many art historians regard themselves as too lofty—too concerned with the history of ideas, of iconography and so forth—to bother with questions about the mere craft of a painting’s making. I must say, frankly, that I’m not all that interested in what sometimes passes for ‘art history,’ though I am intensely interested in the history of paintings.

“As for evidence,” he went on, “if anything, it’s the other way around: the burden is on them. If you say I’m wrong about the proliferation of lenses and optical devices, then you’ve got to explain how you could get Caravaggio’s lutes just a few short decades after Dürer; how come those skills seem to rise up out of nowhere, spread everywhere, and then disappear just as quickly with the advent of the chemical process, some three hundred years later? How come awkwardness seems to disappear completely from western European art for three hundred years and then just as quickly reappear? It all just happens by itself? That would be the loopy theory.”

But what about the apparent lack of testimony on the part of the artists or their sitters? “Artists are notoriously secretive about the specifics of their technique, always have been,” Hockney replied, “and this would have been especially so in the early modern period, when the projection of such illusion was almost deemed a magical gift—though in many ways it’s no less so today. Does anybody know exactly how Roy Lichtenstein created his effects? Or Morris Louis? Were they telling?

“As for the apparent lack of testimony, for example, by Ingres’s sitters, the fact is—as you saw—the camera lucida is just a brief element of the entire process. It’s tiny; if you didn’t know to look for it, you might not even have paid it any attention. That may be one reason. More generally, the optical tools may just have been taken for granted by sitters as part of the artist’s craft: nothing worth commenting on. If I asked you what it was like having your picture taken by some photo-portraitist today, you wouldn’t reply, ‘Well, he took this boxlike object with a bit of glass in the middle at the end of a stand with a cord he pressed.’ You’d focus on other aspects of the experience, how he set you at your ease, made a nice cup of tea, chatted wittily, and so forth. And furthermore, for all we know, the sitters and witnesses have been commenting on the optical aspects all along; we just didn’t know what words to look for. They may not have said optical device, or lens, or camera obscura … For instance, they may have used the word glass— as in spyglass for telescope, a looking-glass for a mirror—and up till now we weren’t paying attention.”

I could see why Hockney drove some art historians crazy. “He’s a nimble thinker” is how John Walsh had parsed matters for me, his voice brimming with wry affection. “He’s seldom at a loss for answers, even if those answers might seem to overlap in sometimes wildly contradictory ways.”

“And anyway,” Hockney was now saying, “who says there isn’t already plenty of evidence of precisely the sort they seem to be demanding?” He noted how he’d recently begun a fax correspondence with Martin Kemp, the eminent art historian at Oxford University, whose massive 1990 study The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat was studded with suggestive leads. “And my friend David Graves, in London, has been spending time in the British Library, digging up all sorts of things. For instance, here”—I could hear him shu›ing papers. “Right. This: from Giovanni Battista della Porta’s 1558 four-volume treatise Magiae Naturalis—Natural Magic—by which was meant seemingly supernatural phenomena that could be explained scientifically. And here he’s revealing what he calls the carefully guarded secret’ of deflecting images onto a page. ‘If you cannot paint,’ he advises, ‘you can by this arrangement draw (the outline of images) with a pencil. You have then only to lay on the colours. This is done by reflecting the image downwards onto a drawing board with paper. And for a person who is skillful, this is a very easy matter.’ And so forth. So I really don’t know what these historians are talking about: no evidence.”

I began getting faxes on an almost nightly basis—part of a stream of such inspiration that Hockney seemed to be sending out to an ever-widening group of corre- spondents (Martin Kemp, David Graves, Gary Tinterow, and so on). The notes were invariably handwritten. Hockney—this great student of technical wizardry—has never learned to type, and hence shies away from e-mail. For that matter, the fax allows him to send reproductions of imagery, too.

One morning, I found a single sheet on which Hockney had included, side by side, a reproduction of The Art of Painting, by Vermeer (the artist in his silly dark pantaloons, seen from behind, seated at his easel, his model poised gracefully before him), and a witty Triple Self-Portrait by Norman Rockwell (the artist, likewise seen from behind, leaning over to peer, bespectacled, into a mirror as he completes the prettified self-image, without glasses, on the canvas before him). As Hockney subsequently remarked, both images manifestly fictionalized their own creative process; neither artist was in fact eyeballing the painting we see before us. Rockwell famously used photographs to develop his imagery, and Vermeer has been shown by the National Gallery of Art’s Arthur Wheelock, among others, to have blocked out his canvases with the aid of a camera obscura.

Another morning, I woke to find yet another impromptu treatise on Caravaggio’s method. “The more one looks into Caravaggio,” Hockney wrote, the more “one can figure out his tool, which had to be a sophisticated lens.” He went on to note that, as he’d suspected, there were contemporary written references to Caravaggio’s “glass” (“I mention this for the historian of pictures who wants everything in writing so he doesn’t have to look very hard at the pictures and deduce methods”), after which he set out, precisely, to deduce Caravaggio’s possible technique:

He traveled a lot, so the equipment has to be portable, not really very big. So I suggest a lens that is not much bigger than two cans of beans. Some lenses are more sophisticated than others. Today compare the results of a throwaway camera (cheap plastic lens) with exactly the same subject, lighting, and film, [taken] with a Leica. One will be fuzzy edges, all colors tending toward murky green; the Leica will be sharper and with richer and more varied colours. Common knowledge, you might say, but, again, I mention it for those who want it in writing, etc., etc.

The lenses were all hand-made, hand-ground, etc. Caravaggio’s would never have left his person, unless he was using it. In the highly competitive world of painters, no wonder he carried a sharp sword in those violent times.

He worked in dark rooms—cellars.... He used artificial lighting, usually from the top left. He would use models from the street—who else would sit still for him very long?—and was known to work very fast. How long can you hold your arm outstretched even resting on a stand? Try it: you begin to ache under the arms.

So the Supper at Emmaus was set up carefully in a cellar, lit carefully, and then he put his lens in the middle on a stand and hung a curtain (thick material in those days) around it. The room is now divided into a light part and a dark part. He is “in the camera” and the tableau is projected clearly with telescopic effect (notice again how the rear hand is almost bigger than the front hand nearer to you).

He covers the canvas with a rich dark undercoat that, being wet, reflects light back. He takes a brush and with the wrong end draws guidelines for the figures in the composition, to enable him to get the models back in position after [breaks for] resting, eating, pissing, etc.

He rapidly paints on the wet canvas, skillfully and with thin paint, knocking in the di‹cult bits, and then with his virtuosity he can finish by taking down the curtain, turning the canvas round and looking at the scene in reality.

All this sounds perfectly plausible to me. So, say there’s no lens; then give a reasonable explanation. Remember: there are no drawings, no notes.

Goodnight, D. Hockney

Good night indeed: I noticed that the fax had been sent at two-thirty in the morning, his time.

I subsequently spoke with Gary Tinterow about this particular piece of Hockneyan speculation. We happened to be looking at one of the Met’s own Caravaggios; he crouched at the side of the canvas and urged me to look up with him. “It’s interesting about Caravaggio,” Tinterow said. “Because the fact is that when you look at his paintings in a raking light like this, you can indeed still make out the marks made upon the canvas by the blunt end of the brush or a stylus as it traced out the contours of the various forms.”

Thinking further about Hockney’s scenario, I was reminded of the strange old performance tradition of tableaux vivants, in which society types would go to great lengths to gussy themselves up as figures in old-master paintings, painstakingly staging the costumed pose, lighting it just so, and then holding it like that, frozen, for minutes at a time before an admiring audience. For a moment, it seemed to me that in such situations the canvas itself had been transformed into a sort of time prism, veritably projecting one group’s frozen pose across the centuries onto another entirely different such group.

FIG 46 Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1601-2.

In a similar frame of mind, another afternoon, I was leafing through Hibbard’s monograph when I came upon a reproduction of Caravaggio’s astonishing rendition of The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, from the Staatliche Schlösser in Potsdam (Fig. 46). Christ stands to one side, gingerly pulling aside the cloth draping his torso so that a manifestly peasant Thomas, backed by two other street types, can literally poke his finger into the gash in the risen Messiah’s flank. And for a fanciful moment I found myself wondering whether Caravaggio’s composition might not contain a subliminal allusion to the dumbfounding hole-in-the- curtain methodology of the painting’s very creation.

FIG 47 Diego Rodriguez Velázquez, Triumph of Bacchus (Los Borrachos), 1628.

I tried such notions out on Hockney a few days later during another phone conversation, and the part he homed in on was this business of the evident street-class nature of Caravaggio’s models. “Because, you see, that’s the point,” he said. “These methods have certain subjects and ways of treating them built into them. The street urchin down the lane becomes a god, an angel, an apostle, because he’s the only one with the time and willingness to pose, or anyway the only one the painter can afford to pay. The well-scrubbed society types wouldn’t bother—except maybe, years later, as a sophisticated form of divertissement. But that’s why you now start getting these sorts of faces in such heightened contexts. It’s exactly the same thing, some years later, with the early Velázquez: the same sorts of faces in the same sorts of contexts [Fig. 47]. And look at those, while you’re at it: the fleeting expressions, the open mouths, the self-conscious grins. . . .”

About a week after I’d got Hockney’s Caravaggio treatise, my phone rang me awake way before seven: there was a whistling on the line. “Oh, dear.” Hockney’s voice came rising through the whistle. “What time is it?” It turned out that he was call- ing from Canberra, Australia, where he’d gone to deliver an early version of these ideas as a lecture. Frank Stella, another Caravaggio enthusiast, was in attendance and, according to Hockney, he’d said to him afterward, “I’m sure you’re right.” Hockney apologized for waking me, but went on, “Listen, love, there’s a book you have got to get. That Taschen book: The Portrait. Norbert Schneider. I picked up a copy this afternoon at the museum here, and it’s incredible. The first page, in the introduction, Schneider writes—he’s talking about the late fifteenth century—‘It remains a source of continual astonishment that so infinitely complex a genre should develop in so brief a space of time, indeed within only a few decades.’ Continual astonishment: he’s talking about the arrival of the lens, and he doesn’t even know it. But I’m absolutely convinced of it. The plates are amazing. Get the book and we’ll talk later.”

I did—it is a beauty—and that evening the phone rang again; it was Hockney, almost breathless with excitement. “You have the book?” he asked. “Good. Because I think Schneider’s right. It happens before Dürer. Dürer is showing an old way in those woodcuts.” He instructed me to turn to a page that featured a small color reproduction of Giovanni Bellini’s portrait of the doge of Venice, circa 1500—an extraordinary painting (Fig. 48). Then he told me to turn to the opposite page, which was filled with a detail of the doge’s face in black and white or, rather, sepia. “And there you can really see it,” Hockney said. “Something about the sepia tonalities, perhaps, but the image looks for all the world like some antique 1870 photograph of an Indian raja.”

The effect was indeed uncanny. Stripped of its color, recast in black and white, the image did indeed look exactly like a photograph, and the doge like our virtually immediate contemporary. (I was momentarily reminded of a similarly uncanny, if diametrically opposite, effect I’d experienced some years earlier on first gazing at a book of Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii’s 1909 color photographs for the czar: Count Tolstoy, a rug merchant, a beautiful young woman. How, I remembered thinking, stupefied, could they possibly ever have existed in color?)

“Look at the detail of the tight embroidering around the doge’s cap,” Hockney went on, “how precisely the pattern follows the contours of the cap—your eye thinks it’s lying there perfectly. No way, absolutely no way that could have been eyeballed, no way mathematical perspective could account for such precision.”

FIG 48 Giovanni Bellini, The Doge Leonardo Loredano, ca 1500.

FIG 49 Hans Holbein the Younger, The Merchant Georg Gisze, 1532.

Hockney then had me turn to a reproduction of Holbein the Younger’s 1532 portrait of Georg Gisze. He pointed out the highlights on Gisze’s sleeve, and how precisely the geometric pattern follows the rug as it falls over the edge of the tabletop. The glass vase, the pestle, both perfect, rest perfectly on the tabletop. “Your eye knows they’re right,” Hockney insisted, now guiding my attention to “that curious cylindrical brass canister on the table between them [Fig. 49]. Because something’s wrong: I mean, itself it looks right, but something’s wrong with how it’s resting on the tabletop. It’s as if it had been added as an afterthought, a separate projection, which didn’t align quite right. Right?”

Hockney was warming to his theme. I realized that it must be six in the morning for him, and I wondered whether he’d slept at all. He directed me to turn to a Raphael painting, circa 1517, of Pope Leo X (Fig. 50). “Look at the thick brocade of his sleeve: perfect,” Hockney said. “I was talking with a historian the other day about this picture, and he stopped me cold. What was I talking about? There couldn’t possibly have been any lenses in 1518. Galileo doesn’t happen till 1609, Leeuwenhoek is more like 1660. ‘Oh yeah,’ I countered. ‘What do you think that is in the Pope’s hand?’” Sure enough, Pope Leo was holding a magnifying glass. “And, of course,” Hockney said, “it stands to reason that lenses would first have been prized by popes and kings, the wielders of power, and, in turn, their court painters—accurate portraiture being such an important aspect of their rule—and only later, maybe even much later, by scientists and academics and their lowly like.”

FIG 50 Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), Pope Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi, ca. 1517.

He paused for air, but not for long. “And, by the way, look at which hand the Pope’s holding his lens in.” The left. “I was talking with another historian the other day, and he assured me that no left-handed person would ever have been allowed to become pope in those days: the left was the devil’s hand. Sinistra. But that’s the effect you would get, in the early days of lens projection, if you hadn’t yet learned to compensate for the reversal caused by the lens. For that matter, look through the rest of the book: Lorenzo Lotto’s Man with a Golden Paw, in which the paw in question is clearly being held in the guy’s left hand. Doesn’t it seem to you there are an inordinate number of left-handed people in this book?” He paused again before positively exulting, “I’m right. I’m right. I’m more certain of it every day.” Whereupon he rang off. A few weeks after that, Hockney was back in New York, addressing the Ingres symposium at the Met. His presentation was the last of the day, following public talks by such art historians as Thomas Crow (on Ingres and David), Jack Flam (on Ingres and Matisse), and Robert Rosenblum (on Ingres’s progeny, from Gérôme to Picasso).

During his slide show, Hockney went over much of the material he’d been rehearsing with me and with others over the previous several weeks—Ingres, Warhol, Caravaggio, Bellini, Raphael—but he added some newer material as well. For instance, he devoted more time to Velázquez, Van Dyck, and Rubens (an oddly anomalous eyeballer). He’d developed a charming riff on early modern Spanish still lifes, especially the work of Juan Sánchez Cotán (1561–1627), a master of sliced melons (“the lutes of the vegetable world”) and cabbage heads. “How long do you think a cabbage like that one would have lasted in those days, prior to refrigeration, in a strong light like that?” Hockney challenged his audience.

Later, during the question period, someone in that audience asked the historians what they made of Hockney’s theory, a question that drew a long, somewhat embarrassed silence, though whether the embarrassment was for themselves (at never having noticed such a thing before) or for Hockney (how could anyone publicly champion such ridiculously grandiose claims?) was not immediately apparent. One of the historians hazarded the predictable “But there are no documents.” To which Hockney responded with his growing arsenal of ripostes, culminating in the faux-modest “I mean, I’m only speaking from my experience as an artist, though surely that must count for something”—which brought down the house.

Hockney returned to Los Angeles, and his fax and phone updates resumed apace. “Heresy,” he announced one evening over the phone. “It turns out that della Porta got himself arrested, playing with these effects. Earlier, in the thirteenth century, when Roger Bacon wrote to the pope about lenses, he was told to shut up and get himself back to Oxford. And, of course, Galileo. The Inquisition. Lenses were still dangerous things, highly suspect at the dawning of the scientific age. No wonder they aroused so much secrecy. No wonder there’s so relatively little written evidence about them.”

“America!” he announced on another occasion. “Doubtless it won’t have been lost on you that the lens begins to proliferate across Europe almost simultaneously with the discovery of the New World, a discovery that, in turn, required its own breakthroughs in lenses and optical measuring and navigational devices of all sorts.”

Then, just the other day: “But of course it’s all coming back together again nowadays. I mean, the rupture between photography and modernist painting. What else is one to make of the news these days? All the revelations about the ease with which journalistic photo editors are regularly altering their digitally based images. The computer changes everything: pixels rather than negatives, the hand back inside the camera! That’s what the Guardian’s picture editor must have meant when he got found out in one of those mini-tempests: ‘Ah,’ he said, we’ve been caught with our fingers in the electronic paint box.’ From this day forward, one might want to say, paraphrasing Delaroche, chemical photography is over! The monocular claim to univalent objective reality is falling away once and for all, and we are being thrust back on ourselves, forced to take responsibility for the way we make and shape our realities, with eye and hand and heart. Who knows where it all will lead? But it’s a very exciting time.”

It had been an exciting couple of months for me, at any rate, trying to keep up with the pace of Hockney’s rampaging discoveries. Sometimes I wasn’t sure. Some of his arguments verged on the tautological: if the rendering was assured, the methodology had to have been lens-based; if it was groping or awkward, it couldn’t possibly have been lens-based; therefore, assured rendering proved the presence of lenses. Weren’t his claims perhaps too broad? I mean, all art over a three-hundred-year swath founded on lens-based techniques? Might it not, rather, have been a case of perceptual hegemony—that a lens-based look came to be deemed real, and that artists, through a variety of techniques, were now required to hew to that standard? And what of virtuosity? Mightn’t certain artists who began by using lenses eventually have graduated beyond them, having got the proportions and the vantages into their very bones, so to speak? And couldn’t one imagine visual prodigies, individuals who might never have required such aids? One speaks of a musician having perfect pitch, of certain readers having a photographic memory of everything they’ve ever read. Might not it likewise be possible for certain artists (say, Velázquez) to have a photographic memory, as it were, of everything they saw—so that, for example, it wouldn’t matter if the cabbage rotted; they would have it whole in their minds and could paint it at their own slow sweet confident leisure?

At other times, however, such hesitations seemed like quibbles. It was as if Hockney had laid a camera lucida across five hundred years of art history, projecting the entire expanse in vividly novel detail. And who cared, finally, if Hockney’s version of history was to actual history what Hockney’s version of a pool is to an actual pool? Which would one rather look at?

One day, I asked John Walsh what he made of the general arc of Hockney’s theory. “Oh, I don’t know about vast historical arcs,” he said. “Maybe there is such a thing. But it seems to me history is far more circuitous, filled with starts, stops, backsliding, lurches forward. In the end, though, none of that really matters, because in the end nobody is expecting a killer theoretical tome from Hockney. What one awaits, with ever mounting anticipation and excitement, is how he’s going to interweave all these fresh insights into his own ongoing work—what fresh new art all this is going to provoke.”

A version of this essay originally appeared as an Onward and Upward with the Arts piece in The New Yorker of January 31, 2000.