When a version of the preceding chapter first appeared in the January 31, 2000, issue of the New Yorker, it provoked a veritable Niagara of response. I write about all sorts of things—hell, I write about relations between Jews and Poles, for God’s sake—so I’m used to getting letters. But I’d never found myself on the receiving end of anything like this. It turns out that the question of technical assistance may be the Third Rail of popular art history. Most people, it seems, prefer to envision their artistic heroes as superhuman draftsmen, capable of rendering ravishingly accurate anatomies or landscapes or townscapes through sheer inborn or God-given talent (talents, which in a corollary to this conviction, somehow seem simply to have dried up, for the most part, over the past hundred and fifty years). Back in the Old Days, I was repeatedly told, artists just knew how to draw—they wouldn’t have needed, and certainly wouldn’t have deigned sully themselves with, cameras or lenses or prisms. Hockney’s observations were by and large dismissed as the self-serving rationalizations of an envy-addled latter-day midget—though sometimes in terms not quite so stark. Nor were professional historians, for the most part, any more open to Hockney’s surmise. (In fact, theirs were some of the rudest ripostes.)

Granted, such revulsion was hardly universal. Maybe a third of the letters came from individuals who’d long harbored suspicions about this artist or that, without perhaps ever having been quite able to articulate them; or else from other individuals with this or that stray scrap of information, which suddenly made sense in the context of Hockney’s wider puzzle; or from others still who were simply charmed and energized by Hockney’s vaulting speculations. (And even a few historians numbered among this group.)

One of the more unusual dispatches of this latter sort came from a professor named Charles Falco, who introduced himself as chair of the condensed matter/ solid-state physics program at the University of Arizona in Tucson. He averred no particular artistic expertise, or even that much interest, unless you included his thralldom to the aesthetics of motorcycles. Living out there in the desert, he’d compiled a superb collection of vintage bikes and was known for his spare-time expertise in that field—so much so that when the Guggenheim began assembling materials for its celebrated 1998 Art of the Motorcycle show, staff members there had initially come to ask him for advice and to borrow the odd bike or two and ended up marshaling his services as cocurator of the entire exhibition. One of his Guggenheim collaborators from those days had spotted my article and sent it on to him, and now Falco was contacting me to say that though his main scientific enterprise these days consisted of running an extremely high-tech lab (one of the most lavishly funded in the country, as I subsequently found out) devoted to figuring out (among other things) how to narrow the thickness of the layer of cobalt atoms arrayed on the surface of a silicon wafer from their current six hundred down to a single one (with the consequent increase in computer-chip e‹ciency such a breakthrough would entail), this work had forced him to become expert in quantum optics, which in turn had required his becoming proficient in standard optics as well. A proficiency, he went on to suggest, that might prove helpful to Hockney in his ongoing researches.

I put the two of them in contact with each other, and a few weeks later I flew out to LA. to join Falco on one of his first visits to Hockney’s studio. The two had hit it off immediately: and it turned out the ride was only just beginning.

Hockney, for his part, had hardly been standing still.

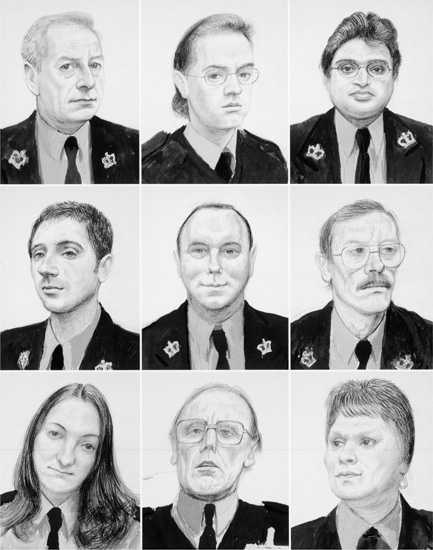

For one thing, he’d continued burrowing into his own series of camera lucida portraits, probing the medium (for both its promises and limitations) and honing his skill (“It’s not that easy,” he insisted. “The truth is, if you need the device in order to be able to draw, it won’t be of much use at all. On the other hand, if you don’t, it can be immensely useful.”) Most of his subjects were friends and new fellow explorers (notably including Martin Kemp, the Oxford historian whose Science of Art is arguably the premier book in the field and who was to become a frequent fax correspondent in the months ahead), and by the spring he was mounting a show called Likenesses, of forty such works, at UCLA’s Hammer Museum. Later that season, as his contribution to the millennial Encounters show at London’s National Gallery, in which over twenty contemporary masters had been invited to perform riffs on particular masterpieces by their predecessors lodged within the museum’s bounteous collection, Hockney chose to honor Ingres himself by performing a variation on that master’s feat of capturing perfect likenesses of British aristocrats who’d visit his Rome studio for a single session in the midst of their European Grand Tours. Reversing the class polarities, Hockney had the museum select twelve guards, previously unknown to him, whose images he now endeavored to capture, likewise in a single sitting, and likewise (or so he insisted) through the initial deployment of a camera lucida. Although Hockney made no claims for the relative parity of the resultant images (Ingres, after all, being one of the greatest draftsmen of all time), the effect was nonetheless quite powerful: for one thing, visitors to the museum often got to witness Hockney’s version side by side with the living models. (The guards, normally invisible watchers, were thus suddenly transformed into objects of intense scrutiny themselves—had that guard there been one of Hockney’s subjects? how about that other one there? For that matter, forget the art; look at the density of that living face right over there! For a short period, strolling through the museum, one was invited to gaze upon passing faces with the same focused regard an artist might.) Beyond that, there could be no doubt as to the similarity of the “ look”; and in fact, more uncanny yet, many of the guards turned out to a startling degree to look just like several of Ingres’s own aristocrats, as Hockney, with his encyclopedic visual knowledge of Ingres’s portraits, was able to demonstrate with a sly grid alignment of his own (Figs. 51 and 52).

In London, with the protean assistance of David Graves, his tall, lanky, and astonishingly competent aide, Hockney had likewise continued burrowing into libraries and archives for any further scraps of evidence they could muster. Back in his Hollywood home, with Graves still in tow, Hockney now cleared the long two-story-high wall of his hillside studio (the studio retains the general dimensions of the onetime tennis court over which it was built), installed a color photocopier in the middle of the space, and, drawing on his brimming private horde of art books and monographs, effectively proceeded to photocopy the entire history of European art, shingling the images one atop the next—the year 1300 to one side, 1750 to the far other, northern Europe on top, southern Europe below—a vast, teeming pageant of evolving imagery (and in some ways Hockney’s most ambitious photocollage yet) (Plate 23).

FIG 51 David Hockney, (top left) Ron Lillywhite, London, 17 December 1999 (detail); (top center) Devlin Crow, London, 11 January 2000 (detail); (top right) Pravin Patel, London, 5 January 2000 (detail); (center left) Jack Kettlewell, London, 13 December 1999 (detail); (center) Graham Eve, London, 7 January 2000 (detail); (center right), Ken Bradford, London, 20 December 1999 (detail); (bottom left) Maria Vasquez, London, 21 December 1999 (detail); (bottom center) Brain Wedlake, London, 10 January 2000 (detail); (bottom right) Fazila Jhungoor, London, 18 December 1999 (detail).

FIG 52 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, (top left) Dr. Thomas Church (detail), 1816; (top center) André-Benoit Barreau, called Taurel (detail), 1819; (top right) Charles Thomas Thruston, 1816; (center left) Jean-François-Antoine Forest, 1823; (center) Guillaume Guillon Lethière (detail), 1815; (center right) Portrait of a Man, Possibly Edmé Bochet, 1814; (bottom left) Portrait of Madame Adolphe Thiers, 1834; (bottom center) Monsignor Gabriel Cortois de Pressigny (detail), before end of May 1816; (bottom right) Madame Louis-François Bertin, née Geneviève-Aimée-Victoire Boutard (detail); 1834.

When, he was asking, and where does that optical look first emerge? And with the procession of European art splayed out like that, the answer was as patent as it was unexpected: far before Caravaggio, and not even in Italy. Rather, in Bruges, where, basically across the single decade on either side of 1425, a group of Flemish masters (the Master of Flémalle, who was most likely Robert Campin; Jan van Eyck; Rogier van der Weyden) almost from one moment to the next, without any awkward groping toward proficiency, evinced a seemingly instantaneous mastery (as if one morning European painting had simply gotten up and put on its glasses)— and there it was, out of nowhere, the optical look, which would now spread rapidly and, as Hockney would indicate for visitors with a triumphant sweeping gesture, come to dominate European painting for the next four hundred years.

The claim was almost literally revolutionary, a turning of the traditional account on its head. Italy, after all, had long been deemed the font of the Renaissance, from which the rebirth of classical knowledge spread outward in the early 1400s, in particular owing to the (re)discovery and elaboration of a mathematically rigorous and idealizing one-point perspective. Van Eyck and his cohort were often referred to as “Netherlandish primitives” because they hadn’t yet attained that new knowledge (they were only able to portray things as they were, went the traditional critique, not as they ideally ought to be). But here Hockney was (he’d lately taken to loping up and down the Wall, sporting a V-neck T-shirt emblazoned with the legend I KNOW I’M RIGHT!), both discounting the importance (and the pervasiveness) of Italianate one-point perspective and highlighting the countervailing spread of the northern optical look. “It’s easy to see how the early art historians got it wrong,” Hockney would cluck to visitors before the Wall. “Modern art history gets going more or less around the same time as the invention of chemical photography, in the middle of the nineteenth century, and by then, if you were a British or a German academic, where were you going to want to be spending your summers, in dilapidated industrial Bruges or amidst the golden rolling hills of Tuscany?” (He ought to know, this child of dreary Yorkshire who’d long ago transplanted himself to sunny Southern California.)

For all Hockney’s certainty (and Graves’s steadily mounting corroborating research), the theory was still subject to substantial qualms. Apart from the evidence of the pictures themselves (and Hockney’s insistent claims that he could plainly make out a lens-based optical “look”), the corroboration was mostly circumstantial (for example, indications that lenses of a certain type might indeed have existed at such and such a moment, somewhat earlier than had been thought). Skeptics were quick to advance other possible theories, and meanwhile, there was precious little evidence that lenses had been in widespread use in Bruges, of all places, as early as 1420.

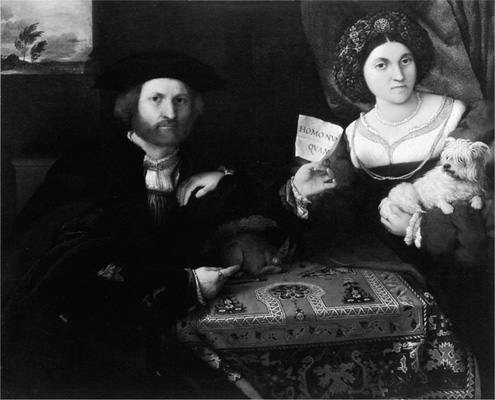

This was the state of play when Falco arrived on the scene early that March. Hockney had immediately led him up to the studio, and the two men had traipsed up and down the Wall, like a pair of generals reviewing their troops, with Falco on the lookout for a specific sort of image, a picture with a particular set of characteristics, an image like . . . like . . . like this one here. He’d speared a reproduction of a painting by the Venetian master Lorenzo Lotto, the Hermitage’s Portrait of a Husband and Wife, dating from about 1543 (which is to say roughly a century after Van Eyck and three-quarters of a century before Caravaggio); he took it down and brought it over to the worktable (Fig. 53). “See,” he’d explained, now repeating the explanation for my benefit, “the husband and wife are sitting on the far side of an intervening table and, as it happens, there’s a Turkish carpet draped over the table, with that regular repeating triangular border pattern running along the edge facing us.” Falco, a mustachioed dervish, may be the only person I’ve ever met who can even begin to approximate Hockney for sheer exalted enthusiasm. “Now, whether that’s centimeters or inches, whatever, those triangles make up a regular repeating pattern, and the point is we can use their modular dimension as the basis for a series of measuring calculations.” He whipped out a notepad and threw himself into a dizzying array of calculations, muttering merrily away about image size and subject size, lens-image distance, magnification, average spacing between the pupils of the sitters’ eyes (though such calculations seemed entirely second nature to him, he was leaving even Graves in the dust), presently emerging with the claim that Lotto would most likely have been using a lens with a diameter of roughly 2.4 centimeters and a strength of, let’s see, 1.86 diopters (“roughly the equivalent of a pair of reading glasses”), with a depth of field (the depth before the image went out of focus) of about 22 centimeters.

But what sort of claim was this? “Well,” he went on, “it’s a scientific hypothesis, which we’d now need to test against other details in the image. And see, here”— he jabbed his finger at the middle of the table—

“Yes,” Hockney interrupted, “David and I already noticed that, too. The border pattern juts back into the middle of the table there in a sort of arch, but there at the back it goes out of focus, which would have been impossible for an artist to see, let alone replicate, without witnessing the effect projected onto a flat surface by some sort of lens. After all, the moment he would have tried to attend to that out-of-focus patch, it would have gone into focus for him. Whatever we look at is always by definition in focus as we look at it.”

FIG 53 Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Husband and Wife, ca 1543.

FIG 54 Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Husband and Wife (detail), ca 1543.

Falco nodded. “Yes, and it goes out of focus at the right spot, according to our calculations, about twenty-two centimeters back. And furthermore, you’ll notice that beyond that, the image is back in focus again, which means Lotto would have had to refocus his lens, either by moving the lens, or the canvas, or the table, but (think about what happens when you refocus a zoom camera, the lens telescoping either out or in) that would have subtly affected the magnification, the two parts would not quite have jibed, and you would expect furthermore”—he pulled out a ruler and traced the front part of the receding pattern, and then its back part (Fig. 54)—“and, yes, you get it: rays receding back to two entirely different vanishing points. This painting was obviously not accomplished according to some mathematical model. Assuming our hypothesis is correct, the same sort of thing should be happening elsewhere in the picture, for example here, on the right-hand edge of the table, where the receding triangular pattern at first seems to stay in focus all the way back; the band is narrower here on the edge than with that arch there in the middle of the table, and hence it would have been easier for Lotto to fudge. But if we take out our ruler, I bet you it will turn out that”—pen swipe, pen swipe—“yup, the vanishing points again differ for the front and the back, by the slightest but still an identifiable degree.

“That,” he rose up, smiling, triumphant, “is what in science we refer to as a proof.”

(“You make a prediction,” he would subsequently recount for me, as we discussed that first day and the Lotto painting which he’d taken to referring to as “our Rosetta Stone”—“you make a prediction, and then it holds true. We like that in science. It’s strange,” he went on, surveying what by then had already grown into several months of collaboration between him and Hockney, “but had either one of us maintained all of this on our own, nobody would have believed us. But together …” He let the thought trail off, breaking into another wide smile.)

Hockney and Falco were almost slaphappy with excitement at this point, and I hated to be the one to throw a damper on things, but, still somewhat skeptical, I broke in, “That’s all fine and good, but what about back over here, with Van Eyck in Bruges? Isn’t the problem that there’s no good evidence of the existence, let alone widespread dissemination, of such lenses, at that place at that time?”

None of us was subsequently able to recall precisely what Falco said in response (as far as he was concerned, he was only repeating what every optical scientist would know, though, as I was subsequently able to determine, hardly a single art historian seemed to know it)—but somewhere buried in the subclause of a subclause of his response, he noted how, “Of course, a concave mirror has exactly the same optical properties as a lens”—a throwaway comment that veritably stunned Hockney and Graves.

Really?!

“Sure,” Falco continued. “Try it yourself. In the morning, in the bathroom, take your shaving mirror—you know, the one that magnifies the image of your face— you may want to narrow the f-stop a little, for maximum effect, wrap a little bagel of cardboard around the outer circumference of the mirror—anyway, when it’s bright outside and still dark on your bathroom’s inner wall, aim the lens at the world outside the window so the gathered light bounces off the mirror and onto the darkened wall, move the mirror in and out till things cast there onto the wall come into focus, and what you’ll get is a Technicolor perfect image of the world outside. Upside down, granted, but incidentally not right-left reversed, as would be the case with a lens.”

As Falco had been expounding, we’d all drifted on over to the 1420 section of the Wall. “You mean,” asked Hockney, “a mirror like this, or this, or this?”—he jabbed at one image after another, for almost simultaneous with the proliferation of the optical look there in Flanders, there had occurred a proliferation of mirrors in Netherlandish paintings.

“Well,” Falco concurred, “those are all convex, which is to say bowed outward at the center. You’d need to turn them around but”—we’d come to Van Eyck’s celebrated Arnolfini Marriage (1434) (Fig. 55), with its mirror dead center on the far wall, at the focal point of the entire painting, the master’s ornate signature, “Johannes Van Eyck made this,” immediately above it. “But once you did—and remember, in those days the back side of a mirror wasn’t blackened; they just silvered the bottom of a globe of blown glass and sliced out the circular segment—you’d have a concave mirror, and in fact, a mirror quite like that one may well have been used to construct this image. Now, of course, such a mirror would only have had a sweet spot of around thirty centimeters”—a zone of focus, an invisible sphere or globe, as it were, 30 centimeters from side to side and front to back—“so that the artist would have had to move it around, refocusing, with the consequent multiple overlapping vanishing rays. I’m sure if we spent a little time studying this image we’d come upon all sorts of anomalous . . .”

And hence, I pointed out, the lack of unified one-point perspective which, as far as the Italianists were concerned, still rendered these images so “primitive.”

“Whereas, in fact, the visual intelligence and sophistication involved here,” Hockney countered, “the way in which the perspectives are layered, one upon the next, is of the very highest order. Not in the least bit primitive.”

Up to that point, critics of Hockney’s theory, especially its maximal Flemish claims, had been castigating him over the lack of evidence for the existence of the lenses or flat mirrors they’d imagined crucial to the process (after all, the Flemish seemed only to have had those reflection-warping convex mirrors, and what good could they possibly have been?), whereas it now turned out that it was the flat mirrors that would have proved useless, and only curved mirrors, with their ray-concentrating properties (the same properties, as Falco pointed out, that had led Archimedes to deploy them as burning lenses to defend Syracuse from besieging flotillas), that would have done the trick.1

FIG 55 Jan van Eyck, The Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and His Wife Giovanna Cenami(?) (The Arnolfini Marriage), 1434.

“For example, look at that chandelier,” Hockney now crowed (he’d immediately grasped the implications of Falco’s throwaway comment about the concave mirror). “There’s another one there, and there, and there”—he was pointing all about that 1420s Netherlandish region of the Wall. “There’s no way anybody before that could have recorded such an astonishingly accurate and assured rendition of a chandelier.” He pointed back at some earlier approximations, in Giotto and others. “Nor is there any way Van Eyck could have achieved it with one-point perspective, either. But here suddenly they’re all doing it, almost as if to say, ‘Commission me to do your portrait and I’ll throw in that chandelier for free.’”

“And keep in mind who this is,” Graves now interceded. (He seemed to have become as encyclopedically grounded in the history of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century art history as Falco was in the physics of curved mirrors.) “Mr. and Mrs. Arnolfini. He’s an Italian merchant, resident in Bruges—Florentine, and in fact the representative on the scene of the Medici Bank. He could easily have taken the knowledge—”

“— one of the most valuable bits of knowledge of its time!” Hockney chimed in.

“Yes,” Graves continued, “taken it back with him to Tuscany.”

The sweet spot of Hockney’s entire theory suddenly seemed to swim vividly into focus.

Falco left that evening, returning to Tucson—not a bad day’s work—but the very next morning, Hockney and Graves and Hockney’s California assistant Richard Schmidt were out alongside the outer wall of a guest cottage on the other side of the compound, building a little outhouse-size art-mirror shed: essentially darkness-enclosing walls with a crisp square outfacing window, and inside a standard shaving mirror mounted on an adjustable pedestal. They’d been studying a drawing Van Eyck had made on the occasion of Cardinal Niccolò Albergati’s one brief visit to Bruges, in December 1431 (Fig. 56). It was a drawing that Van Eyck would use the following year as the basis for his celebrated painting of the cardinal (Fig. 57). “Look,” Hockney commented. “Look at the pupils: little pinpricks. Quite unusual, but exactly the contracted effect you’d get if you’d sat your subject outside in the bright sun.” Graves, inside the shed and adjusting the mirror pedestal, pointed out that the Bruges artists had all been members of the Guild of St. Luke, which, as he now recalled from his researches, happened to be the guild of “painters and mirror makers.” Hockney invited a visiting friend to sit for him outside, swathed the man in a red cape reminiscent of the cardinal’s, climbed into the operator’s cockpit inside the shed, adjusted the mirror—and it was exactly as Falco had foretold: A perfect upside-down image of the man outside was being cast onto the blank sheet of paper Hockney had a‹xed to the wall beside the window. He worked quickly, sketching out the contours of the man’s face and noting the signposts, and then, pulling the page off the wall and flipping it right-side up onto an easel, simply polished off the man’s likeness, in a process that was if anything even more straightforwardly e‹cient than the camera lucida.

FIG 56 Jan van Eyck, Cardinal Niccolò Albergati, 1431.

FIG 57 Jan van Eyck, Cardinal Niccolò Albergati, 1432.

Back up in the studio, a few hours later, marching up and down the Wall again, Hockney was pointing out the profusion of window-framed images that characterized the portraiture of the latter half of the fifteenth century and on into the sixteenth, initially in Flanders and then everywhere. “And usually with very pronounced shadows,” he pointed out, “as if the sitter were outside, even when the sitter is being portrayed as if he’s the one on the inside.”

Presently he zeroed in on a marvelous interior scene, a teeming Last Supper by Dirck Bouts, the central panel of an altarpiece painted around 1466 (Fig. 58). “See,” he said. “Another chandelier, and as with Van Eyck’s in the Arnolfini, painted as if from head-on and not from below. In fact, the heads of each of the disciples gathered around Christ are painted as if close-up and from head-on, as, for that matter, are their feet—and actually, wait a second, wait a second: isn’t that the same fellow seen over and over again, from different angles—Christ and that disciple and that other one over there? Bouts must not have had enough models to stage a full dozen. And then, look over here, the two men in the window looking in on the scene from outside, as if Bouts were providing us with a clue as to how he’d accomplished the whole composition. I recognize this technique, because in essence, it’s the same way I built up my Polaroid collages back in the early eighties: close-up and one framed detail at a time, slowly building out to a sense of wider space. In many ways the opposite of the standard Italian one-point perspective, as in this one over here”—Andrea del Castagno’s 1447–49 version (Fig. 59)—“which in turn mimics a standard single-snap photographic shot.”

Meanwhile, on an almost hourly basis, Falco was chiming in by fax with his own fresh discoveries. (He subsequently told me that the session with Hockney had left him so energized that he’d found it impossible to sleep that night, and that at three in the morning he’d risen from bed, popped his contacts back in, and begun scouring the art books he had rapidly taken to collecting.) There were numerous carpet-draped tables—a Memling from fifty years before the Lotto, Holbein’s portrait of Georg Gisze from 1532 (which had already been the focus of some of Hockney’s most intensive earlier investigations; see Fig. 49)—exhibiting improbably multiple vanishing rays entirely incongruent with any mathematically perspectival approach. (On the lower right-hand side of the Gisze panel, as Hockney himself now noticed, the table just seemed to fall away completely: very odd. Graves, for his part, was becoming convinced that the curious little canister with the mysterious slot opening on the table in front of Gisze’s forearm might itself be some sort of optical device: couldn’t that little highlight inside the slot be the glint of a tiny mirror?)

FIG 58 Dirck Bouts, Last Supper, ca 1466.

FIG 59 Andrea del Castagno, Last Supper, 1447–49.

Furthermore, Falco had been researching the Cardinal Albergati drawing and its subsequent painting. It turned out that while the drawing was 48 percent of life-size, the final painting was 41 percent larger than the drawing, the sort of thing that gets obscured in art books (such as this one) that reproduce the two images side by side and at the same scale. And yet, Falco noted, if you make a transparency of the drawing and blow it up to scale and place it over the painting, the lines match up almost precisely—the forehead, the pupils, the nose, the lips—far more so than could be accounted for by mere eyeballing, and impossible to have accomplished by the pinprick-and-charcoal tracing method advanced by some art historians as the likeliest technique when the scale of the drawing and the painting is identical. (The drawing had in any case never been pinpricked.) No, Falco maintained, the likeliest scenario involved Van Eyck’s having deployed some sort of prior-day epidiascope (or opaque image projector)—and if he’d used such a thing to transfer the image, why would he not have used a similar device to make the image in the first place, especially when he’d been granted so little time with his distinguished sitter? Furthermore, as Falco related in a subsequent note, the failure of the transparency of the drawing to line up perfectly with the painting was itself highly revelatory: the front half of the face did, but the ears and back of the head were off by a few degrees. If, however, you shifted the transparency left two millimeters and up four millimeters, the ears and the shoulder squared up perfectly (while the front of the face went out of whack). Wasn’t it likely, Falco surmised, that Van Eyck or some assistant had simply bumped up against the mirror, or the easel, or the work-table, in the middle of the transferring process, therefore accounting for the barely perceptible double exposure?

Falco, like Hockney, proved a veritable logorrheic on the fax machine: his steadily accumulating dispatches, of which I was being sent copies, would come to fill two huge binders on my shelf (at times I felt as if I were eavesdropping on Freud and Fliess), with Hockney’s to Falco and Kemp and others swelling another several folders. Of all Falco’s myriad observations and calculations in the months ahead, one of my favorites would involve the famously elongated smear of a skull at the bottom of Holbein’s 1533 painting The Ambassadors, another of Hockney’s own most cited works (Fig. 60). Hockney had always admired the “marvelous accuracy of the foreshortening” in the anamorphic skull, rendered all the more palpable when subjected to computerized restoration. But Falco noted how the compressed version still “bothers me every time I look at it.” And he’d now figured out what the problem was: “The back of the skull is far too big—and if you look at the top of the skull, it’s clear it’s made of two curves. This happens at an appropriate depth into the scene for Holbein to have had to refocus, had he used a lens. If you slice the attached fax at this joint (that is, where I drew a vertical line) and slide the back portion of the skull to the left by one inch and up by a half inch, not only does the skull take on a much more human look, but several important lines and features Holbein painted on the two portions of the skull line up.”

FIG 60 Hans Holbein the Younger, Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve (The Ambassadors), (computer-manipulated detail), 1533.

Forget Freud and Fliess. Other days, I imagined I was eavesdropping on the earliest days of plate tectonics theory.

During the weeks that followed, back home now in New York, I continued to listen in, mostly by way of cc’ed correspondence, on the ongoing investigation being conducted, principally, by Hockney, Graves, Falco, and Kemp. Graves passed along a curious engraving he’d come upon, the frontispiece of a 1572 Latin translation of the tenth-century Arab scholar Alhazan’s Optics, which featured a panoply of illustrated optical effects: a rainbow, legs refracted in water, and down there at the bottom a very odd little man bouncing the image of his face off a concave mirror (Fig. 61)! Hockney, meanwhile, zeroed in on the Mona Lisa, of 1503, which he said stood out on his Wall as the first instance of the softer focus one actually gets from an image projected (by either a mirror or a lens) into a darkened chamber. (Earlier artists had aspired to more exact measurements, but Leonardo seemed to be approximating the very cast of the projected image.) He also noted the bright light shining down from above (indicated by the deep shadows beneath the nose and lips)—at which point one of the others pointed out that Leonardo, at any rate, certainly knew of the optical properties of the camera obscura, mention of which occurs dozens of times in his notebooks (written in his secret-keeping reverse handwriting, of course). (What didn’t Leonardo know? Hockney marveled in response.)

FIG 61 Alhazan, “Archimedes using burning mirrors to destroy the Roman fleet in Syracuse harbour.”

In a similiar vein, Hockney pointed out how one of the hardest things to master with collaged, multiple-vantage painterly composition was a believably realistic spatial relationship between figures. With Georges de La Tour, for example, for all the French masters splendors, the figures seem separately posed (as they probably were) and seem barely to inhabit the same space. They fail to make eye contact; the spaces between figures are subtly wrong. In The Fortune Teller (ca. 1630, Fig. 62), for example, the girl in the rear is bigger than the young man in the foreground. By contrast, Hockney came to see in the later Velázquez a virtual champion of the technique—again thanks to his softening of the atmospheric contours of the various figures, so that they indeed seem to stand side by side or one behind the other. (In fact, Velázquez’s entire career can be seen as one of consistent progress toward such consummate mastery.)

FIG 62 Georges de La Tour, The Fortune Teller, ca. 1630.

FIG 63 Frans Hals, Young Man with a Skull (Vanitas), 1626–28.

Meanwhile, Frans Hals, of all people, began increasingly to consume Hockney’s attention: strange, because he of all artists seems the most slapdash and spontaneous. Precisely, Hockney countered, but look, for instance, at the amazing foreshortening of the outthrust hand in his portrait of the boy with the red-feathered cap holding the skull, from 1626–28 (Fig. 63). How long could a model have been expected to hold that pose? Keep in mind, there is no charcoal underdrawing, yet the gesture retains an astonishing freshness. Could Hals merely have eyeballed this, Hockney wondered, or was some solid optical structure guiding the quick, fluid brushstrokes?

Presently, Falco invited Hockney to come out and visit him at his Tucson lab, and I decided to join them. On a sweltering, crystal-clear May afternoon, Falco picked us up in his arrest-me-red BMW and squired us over to his air-conditioned lab on the top floor of the university’s ten-story Optical Sciences Center. (On the way, he pointed out that the pristine air and the desert stillness of the atmosphere accounted for the presence of more working telescopes within fifty miles of Tucson than anywhere else on earth.) Once at the lab, we were all required to don head-to-toe pillow-white ghostbuster outfits, complete with shower caps and booties, and then to subject ourselves to an invigorating air shower before breaching the inner sanctum. (Falco explained that some of the experimental chambers within were required to maintain vacuums ten thousand times purer than even the vacuum found in outer space.) We looked preposterous but endearing, I suppose: some while later a faxed photo of the touring group began circulating among us, to which somebody had a‹xed the hand-scrawled motto: “Fifteenth Century Art History: It’s a Tough Job, but Somebody’s Got to Do It.”

Inside, multi-million- dollar contraptions assured the perfect gyroscopic stillness of platforms on which additional multi-million-dollar contraptions assured the yet more perfect stillness of various further million-dollar electron-scanning supermicroscopes. (Suddenly I could see where Falco might have gotten that idea about Van Eyck’s inadvertently jiggling the Cardinal Albergati epidiascope.) “I always tell my students,” Falco explained, “that there are two ways you can be better than everybody else. The first is to be smarter: not that easy; there are a lot of smart people. The second is to have better equipment.”

“Same as Van Eyck,” Hockney deadpanned, without missing a beat.

Falco had an assistant zero in with one of the video monitors hooked up to the microscope. “Let’s see,” he said. “As you can see, that’s an array of eleven cobalt atoms lined up one beside the next.” It was incredible: one could actually count them.

“I think artists and scientists have more in common with each other,” Falco now hazarded, “than either do with the historians of their respective disciplines. For one thing,” he continued, “scientists tend to be deeply visual, that’s how they think, whereas I’m surprised to say that many of the art historians I’ve been talking with lately don’t seem to be visual at all.” Hockney concurred absolutely—this, after all, being one of his favorite stalking horses. (He tends to retain as straw man a stereotype of his art-historical interlocutors, as many of them do of his evolving and increasingly nuanced theory.) “They just don’t get it,” Hockney insisted. “They go on and on as if the artists of that time would have been too unsophisticated or too ashamed to have been using optical devices, whereas on the contrary, these weren’t stupid people, they were keen to make pictures! They weren’t art historians, for god’s sake.” He went on to note Kemp’s comment to him that painters in an era when they hadn’t yet divided off from scientists—we are speaking of a time before that artificial division—far from being ashamed, would have taken pride in their proficiency with optical devices; they’d have been ravenous to deploy any new aid. “And anyway,” Hockney went on, “why is it that mathematical perspective is deemed acceptable as such an aid, but a camera obscura is somehow suspect? I’m sure that wasn’t the case for them.”

Falco noted how he’d been astonished at the relative scientific illiteracy he was encountering not just among the average folks to whom he was endeavoring to explain the team’s optical discoveries, but among the tenured humanities professors as well. “It’s not just that their eyes glaze over at the slightest whiff of an equation”— Hockney and I eyed each other sheepishly—“they don’t even seem to understand the rudiments of scientific discourse. I was laying out our Lotto discoveries for one of the art history profs around here the other day, and he ended up saying, ‘Well, that’s your theory, I just happen to have a different one.’ This isn’t a theory, I just about shouted at him, it’s a proof! It’s established fact. He just shook his head at me, condescendingly. It was incredible.”

The sheer exasperation of it all made us all hungry, so we decided to head out to get a bite to eat. As we left, I noticed a framed photo of Falco astride a veritable beast of a gleaming, souped-up motorcycle in the very middle of his lab. “How did you manage to—” I started to ask. “Long story,” he said, “long story.”

“What’s their alternative theory?” Hockney now asked, as Falco drove us over to the restaurant: he was still fuming. “That one day all over Europe painters simply started receiving postcards saying, ‘Hey guys, the Renaissance has started. Time to ramp up your drawing technique!’”

The conversation segued into a consideration of specific painters. Falco had been studying Petrus Christus, a Netherlandish painter from the generation following Van Eyck. “Historians credit him with being the first guy up there to transcend the so-called primitivist look and attain a one-point perspective, but I think they’ve got it wrong. I think he was just incompetent at moving the lens around.”

We pulled into the restaurant parking lot—brief blast of furnace-hot air between two air-conditioned enclaves—and once inside, after we’d ordered, Hockney pulled out a sheaf of photocopied reproductions he wanted to go over with Falco. The first was a Van Dyck, a circa 1626 portrait of a seated Genovese matron with her son standing beside her: quite beautiful, quite convincing, until you gave it a second look (Fig. 64). “I mean,” Hockney asked Falco, “if she were to stand up, how tall would she have to be?” Falco, who seldom allowed such challenges to pass as merely rhetorical, whipped out a pen and pocket ruler and began to make napkin calculations: “At least fifteen feet,” he presently surmised. “Mother’s weren’t giants in those days,” Hockney asked, “were they?”

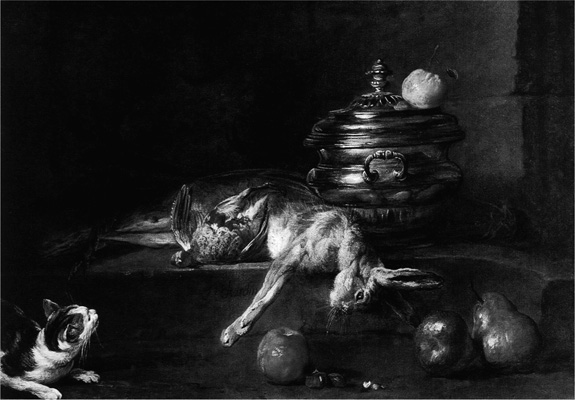

He then pulled out another image, Chardin’s Silver Tureen from the Met, a still life with a cat to one side, a couple of pears off to the other (Fig. 65). “Wonderful painting,” he averred, right from the outset. “Incredible surfaces, truly exquisite rendering. But the pears are as big as the cat, which seems a bit strange—unless, of course, as with the Van Dyck mother and son, they were painted separately, off separate projections.” He pointed out that Chardin was another of those artists from whom precious few study drawings or underdrawings exist; and he was notoriously secretive about his techniques. “The marvelous thing, though,” he continued, “is the way the viewer’s eye compensates, the viewer’s mind actively corrects so that it doesn’t seem strange, partly because we too take the pictures in through a series of details, which we then configure into a seamless whole, and partly because we know this is a cat and that a pear, this a mother and that a son, we know their relative sizes, and we adjust for them accordingly. Our minds do that, the perceiving mind being perhaps the greatest wonder of all.”

FIG 64 Anthony van Dyck, A Genovese Noblewoman and Her Son, ca. 1626

FIG 65 Jean-Siméon Chardin, The Silver Tureen ca 1728.

FIG 66 Jean-Siméon Chardm, Return from the Market (La Pouvoyeuse), 1739.

Hockney pulled out another, if possible still more lovely, Chardin, the sublime Return from the Market of 1739 (Fig. 66). “She’s another tall one,” he noted, and Falco whipped out his pen and pocket ruler again. Following a few quick measurements and calculations, he concurred: “If the space between her pupils were the standard two and a half inches, then she’d have had to be approximately, let’s see, umm, six foot eleven—she’d have had a hard time making it through that door jamb.” Hockney noted that he and Graves had already ascertained that the composition featured at least two distinctly different vanishing points (the back wall rectangular stones and the chest of drawers receded to separate foci), consonant with at least two different projections, one for her lower body and a separate one for her upper half. “But look here,” Hockney went on. “Where’s her elbow? If you look at the picture from below, running up her exposed forearm, it’s at one place. Whereas if you follow her shoulder down, it’s somewhere entirely different. It’s as if her arm has an extra middle bone. This is clearly bothering Chardin as well, because in two other versions of the same painting, he’s still monkeying around with the elbow passage, trying to get it right.”

Falco grabbed back the image and proceeded to hold it flat, extending the page straight out level from his squinting eye. “I’m looking at the door jamb. Yeah, you can see it, you can see the jog, at least one, there might be another. Here,” he said, his finger on the spot as he brought the image back onto the table, “and maybe here as well. That’s what we scientists call ‘sighting along the data.’ You do that sometimes when you’ve got a chart with a splatter of data points; you hold it up from the side and see if you can’t make out a pattern that wouldn’t otherwise be discernible.”

“The point, though,” Hockney went on, “is precisely that unless we focus on the disjunction, we don’t see it. And who focuses on elbows? The lower arm seems fine, the upper as well, our mind makes the necessary elisions, and the painting as a whole feels seamless. Perfect.”

Back at his campus o‹ce, later that afternoon, Falco pulled out a sheaf of his own, the working draft of a piece on their discoveries which he was coauthoring with Hockney and which they would soon be submitting for publication to the Optics and Photonics News, the prestigious monthly of the Optical Society of America, with subscribers in fifty countries (though probably not a single art historian among them). The two reviewed a few outstanding issues, after which Falco drove us to the airport for the flight back to LA.

The next morning, before returning to New York myself, I went up to visit Hockney at his studio. For the first part of the visit we were joined by a distant neighbor of his, the sleight-of-hand artist and antiquarian historian of magic, Ricky Jay. After Hockney demonstrated the mirror shed for him with its upside-down projection, Jay pointed out how forgers too often preferred to work upside down. It made for a more accurate, less mind-filtered copying process. “Here,” he said, grabbing my notepad, penciling a line down its length, and then handing the pad to Hockney: “Go ahead, sign your name underneath the line.” Hockney did so and handed the pad back to Jay, who turned it upside down and, after flourishing his pencil hand a few times theatrically, proceeded to dash off (backwards) an uncannily precise simulation of Hockney’s signature on the other side of the line. “Of course, I’d never dream of deploying such a skill to illicit purpose,” he assured us, whereupon he took his leave.

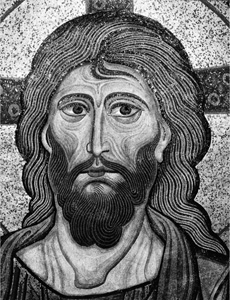

The Wall, meanwhile, had wrapped itself clean around the entire studio, 1750 now continuing all the way around past the invention of photography up through about 1900, which kissed back up against the 1300 corner of the far wall. “Awkwardness,” Hockney was saying, wheeling around, “the disappearance of awkwardness, the invention of chemical photography, and the return of awkwardness. The preoptical,” he wheeled once more, “the age of the optical, and then the post-optical, which is to say the modern. And look here.” He led me over to the corner where the two ends of the procession abutted. On the one wall he’d posited, as endpoint, Van Gogh’s portrait of Trabuc; next to it, on the other, was a medieval Byzantine icon of Christ (Figs. 67 and 68). If anything, the overlapping effect was even more uncanny than that of Ricky Jay’s paired signatures.

The photocopying machine had been pushed over to the side, and the center of the studio was once again teeming with Hockney’s own painting efforts, and in particular a remarkable canvas portraying the view immediately outside the studio: the tree-covered path leading back down to the house. But this was no mere photo-optical approximation. On the contrary, the image, thrillingly precise, somehow was managing to convey not only what was directly before the viewer but what was wrapping up above and below and to the side; it even seemed to be beginning to include what was behind (Plate 24). This was no window, cut out and cut off: this was a world in the process of being entered, a space fully inhabited, enfolding, and receiving: a sort of concave phenomenological bulge. I’d never seen anything quite like it. Next to it, leaning against another easel, was a similar view of the patio outside his London studio. “I wanted to paint that vista from memory,” Hockney explained, “without the use of any photographic aids, only as I was able to reconstrue it in my mind’s eye. And next month, when I get back to London, I’m going to attempt a similar series of views from my breakfast table here, gazing out toward the patch of valley in the distance. Again as a further way of evading the optical bias.”

FIG 67 Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Trabuc, September 5-6, 1889.

FIG 68 Christ Pantocrator, ca 1150 Byzantine apse mosaic Cefalù cathedral, Sicily.

No more lenses, he seemed to be saying. Or rather, maybe, a different sort of lens: his very being reconfigured as a time lens.

A couple months later, when I happened to be passing through London on other business, I paid a call on Hockney at his Pembroke studio, and the LA. vistas were indeed on his easels. (The July issue of Optics and Photonics News was likewise on his table, the Arnolfini Marriage splashed across its cover.) As it happened, Hockney’s staging of Stravinsky’s Rake’s Progress was going to be receiving its twenty-fifth anniversary performance the next afternoon down in Glyndebourne, and Hockney invited me along.

Such celebratory productions are increasingly bittersweet affairs for Hockney, what with his continually encroaching deafness. He no longer participates in the actual staging, and is no longer taking on fresh projects. (Granted, he’s not beyond using his auditory di‹culties to maximum tactical effect. If he doesn’t want to entertain objections to or hesitations about his theories, he simply doesn’t hear them and plows on, oblivious. The deafness may account, at least in part, for what seems a narrowing of his universe, but it also allows for a sometimes awe-inspiring intensity of focus as well—seldom have such proliferating manifold perspectives been pursued with such monomaniacal passion—so it’s a mixed bag.)

At any rate, the Rake’s Progress the next day was as crisp and fresh as ever—a true evergreen staged in a setting of lulling pastoral ease (the grazing sheep on the meadows surrounding the manor bunched and drifting like earthbound clouds)— but the thing that most astonished me was how already, way back then, Hockney had been conceiving of the opera’s Bedlam scenes. Virtually every other conception of an insane asylum I’d ever encountered (from the Bell Jar through Cuckoo’s Nest, from Hogarth through Sweeney Todd) envisioned the madhouse as just that: mad. A tumultuous, roiling chaos. But for Hockney—and remember, this was twenty-five years ago, long before his various photocollage investigations or the more recent spate of theorizing—Bedlam was already a hell of receding one-point perspective, each inmate slotted into his tapering little foreshortening cell in the perfect vise of a cyclops’s gaze (Fig. 69). Already back in 1975, this had been the prospect from which Hockney had clearly been endeavoring to escape.

Back in London the next day, as if in blithe and tonic compensation, Hockney was recalling for me the trip he and Graves had taken to Bruges a few weeks earlier: the paintings, even more lustrous than their most vivid reproductions; the light filtered through the leaded casement windows (pattern-gridded windows that almost forced one to look through multiple vantages); the wood-beamed interiors within which he and Graves had undertaken their own pocket mirror experiments. But the most enthralling experience of all, he went on, had been their side trip to neighboring Ghent to experience Van Eyck’s magnum opus, the altarpiece, in person. “No amount of viewing of reproductions can prepare you for the experience,” he assured me. “For one thing there were the colors: colors you never encounter in nature, and can’t even reproduce on the page, but which we’ve been continually encountering in our own projections. I mean, I recognized that green. And then, there’s the sheer scale. The central panel, with its marvelous Adoration of the Lamb, is almost twenty feet long and over twelve feet high—nothing like the miniature foldouts you get in most monographs.” He nevertheless reached for such a foldout and showed me (Fig. 70). “The point is that such renditions necessarily betray the altarpiece’s essential conceptual genius—the literally hundreds of separate detailed vantages—by homogenizing everything to a single one-point perspective shot. I’ve been talking with the people over at the BBC”—he’d agreed to host a series of documentaries on his new theories, to be aired this October in conjunction with the publication of a book laying out his argument, early galleys of which he’d also been showing me—“and I was telling them, there will simply be no way that they will be able to engage the entire expanse of the Adoration within a single shot. They replied that that was all right, they’d just sweep across the panel in a series of slow panning takes, to which I replied, ‘In other words, you’ll be doing exactly what he did: hundreds of individual vantages, one after the next, bringing every detail up close.’

FIG 69 David Hockney, large-scale painted environment with separate elements based on Hockney’s design for “Bedlam” from Stravinsky’s opera The Rake’s Progress, 1983.

FIG 70 Jan and Hubert van Eyck, Adoration of the Lamb, panel from the Ghent Altarpiece, 1432.

“Now, I may have been sensitized to this in advance,” he went on, “because in a way, and again without in any way wanting to compare the quality of the final products, Van Eyck built up his Adoration exactly the way I built up my Pearblossom Highway”—one of the last and perhaps the most ambitious of his photocollage tableaus.

Hockney pulled out a catalogue of his own work and turned to a reproduction of the piece (see Plate 11). “Again, of course, reproductions distort a fundamental aspect of the work,” he said, “but you can get an idea.” The convergence was indeed startling—almost comically so: Compositionally, the center ditch and fountain pole of the Adoration echoed the median divider of Pearblossom— or, I guess, vice versa; the red platform of the former was mirrored in the stop sign of the latter; and so forth. “The point is,” Hockney explained, “it took me two days out there at that intersection in the desert to photograph all of those details; I had to climb on a ladder, for example, to get the head-on shots of the stop sign, and for that matter to get the proper down-gazing vantages of the foreground asphalt. Those beer cans to the side, I had to get right up close to them and then photograph them from an angle which subsequently would meld with all the surrounding shots I was taking. And all of that is what accounts for the sense of immediacy, of closeness, of being right there, that you get with the final collage—especially if you compare it with a standard single snap of the same scene (see Fig. 29). And I’m convinced Van Eyck was doing something remarkably similar, pulling in close for each face in the crowd, for each clump of trees, for each flower, and then feathering all of those vanishing points one atop the next. After which, for all his trouble, he gets dismissed as primitive’!”

He paused, gazing over at the L.A. vistas on his easels, and from them, apparently, free-associated back over to his upcoming BBC documentary project. “It will have the same title as the book,” he said, “Secret Knowledge, but I’m thinking of giving it its own subtitle: ‘Four Picture-Making Cities: Bruges, Ghent, Florence, and Hollywood.’” He laughed and then grew more serious. “Because, actually, the history of picture making is continuous. Today’s Hollywood epics grow directly out of the tradition of prior history painting: Abel Gance comes right out of David, DeMille directly out of Alma-Tadema, and David and Alma-Tadema, of course, directly out of what had come before: Poussin, Caravaggio, Van Eyck . . . Think of the very shapes and dimensions of the screens upon which movies were projected from the start, and then, conversely, of the lenses and other optical devices with which we’ve been showing that those earlier paintings were themselves created.” I recalled how once, a few months previous, pointing to the deep shadows in a night scene of Velázquez’s, Hockney had quipped, “Day for Night.” Back in the Bradford of his youth, Hockney was now recalling, “My dad used to take us to ‘the pictures,’ that’s what they were called, and they were playing at the Picture Palace. And in fact, looking at things again from the other way around, I think one of the most common misperceptions about the old masters is to imagine them as solitary freelancers, on the order of Van Gogh, for example—the great romantic myth of the artist as anguished and questing loner. Whereas, of course, it’s not for nothing that Van Eyck and Van Dyck and Rubens and Velázquez were all said to have studios. Their studios were like nothing so much as the Hollywood studios of the Golden Age. They had lighting people and lens assistants, costume people and makeup artists, accountants and apprentices, and I’m sure Rubens had two flaming queens in the back in charge of all the hats.” (Of course, one of the ironies here is that both the old masters and Hollywood were among the leading promulgators of that myth of the solitary questing knight.) “Caravaggio, in his cellar studio, arranging his models in their poses, draping the costumes over their shoulders, gauging the light, ducking behind the lens to study the image projected onto his wet blackened canvas, coming back out to rearrange the poses once again—his referent nowadays wouldn’t so much be some other painter as, say, Ze‹relli.”2

Caravaggio had probably been the principal focus of Hockney’s interest, certainly after Ingres, in the earliest phases of his historical investigations, and now, during the latter part of 2000 and into the winter of 2001, the Lombard master seemed to wheel back into the center of Hockney’s purview once again. This was in part owing to the sojourn of the dazzling Genius of Rome show at the Royal Academy in London; Hockney visited the exhibition repeatedly, often in the company of a new colleague-in-inquiry, John Spike, the seasoned Florence-based historian and author of a forthcoming Caravaggio catalogue raisonné. Spike subsequently recalled for me how he’d telephoned Hockney shortly after arriving in town for a few days’ visit and Hockney had insisted that they meet at the exhibit right then, immediately—alright, fine, in twenty minutes. “He is definitely a man on a mission,” Spike commented, “and he is definitely noticing things.” He went on to describe, for example, how the two of them had stood for some time before Caravaggio’s so-called Kansas City John the Baptist, and how Hockney had pointed out the absurd, anatomically impossible appearance of the youth’s rippling abdomen. “The reason is simple,” he told Spike. “It’s another depth of field distortion. He was focusing his lens on the elbow in the foreground, such that the boy’s torso went out of focus. An effect you couldn’t possibly eyeball, but which you couldn’t avoid using a lens projection.” Spike was convinced, but now he returned once again to Hockney’s passionate absorption. “At one point,” he recalled, “a few moments later, I noticed how a stooped old man had stationed himself behind us and was likewise gazing intently. Actually, he didn’t seem to like this particular painting and was muttering under his breath. And you’ll never guess who this was: Henri Cartier-Bresson, the great photographer! Hockney was too absorbed even to notice. Needless to say, it was an uncanny moment for me.”

Back in L.A., later in the winter and into the spring, as Hockney and Graves completed work on their book version of the theory (due out from Thames and Hudson and Viking that coming October), they remained focused on Caravaggio, as I came to realize on another trip out, a few months ago, when Falco happened to be visiting as well. We converged on Hockney’s hangarlike auxiliary studio space down on Santa Monica Boulevard, which had been converted into a vast optical lab.

“Look here,” Hockney veritably crowed, as he drew us over to a black tentlike structure, with thick drapes hanging over a tall metal-pipe modular armature, an easel on the inside of the tent, a sliding lens-bearing contraption at its edge (where the drapes were pulled to the side) and a table on the outside, with a bank of daylight-simulating floodlights bearing down upon it. “Now, watch this.” He placed a highly reflective armor breastplate on the table (remember, we were in Hollywood, after all), so blindingly reflective, in fact, that it was virtually impossible to make out any of its details. “Now, come in here,” he said, pulling aside the drapes. Inside, an image of the armor was indeed being cast, upside down, onto the blank canvas, but with the blinding brilliance subdued, the colors and the composition subtly modulated into an enchanting compositional whole—one that looked, if you’ll pardon the expression, exactly like a painting. Falco had whipped out his calculator and was pointing out that both the luminosity and the spectroscopy of the armor still life were being compressed by the lens—he tossed off a series of numbers. “Or try this,” Hockney continued, scooting outside and replacing the armor with a tumbling swath of satin. Again, out in the bright glare of the floodlights, it was almost impossible to make out the glaring fabric—but inside (the cast image was lovely and deeply affecting) you could easily make out where each of the highlights belonged. “Same thing with wall maps,” Hockney went on. “We were noticing the wall maps in the Vermeers at the recent New York show, for example the one behind the girl in The Allegory of Painting—and we did the experiment. With the naked eye, there’d be such an overload of information—the coastline, the marshes, the borders, and so forth—that it would be di‹cult to make out the creases and folds in the hanging map itself. But when you cast such a scene through a lens, creases and folds are just about the first thing you notice. . . .

“Now, come here.” He drew us back out of the tent and over to a side wall onto which had been pinned a Hockneyesque pastiche of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus of 1601. “We figured out precisely how he did it. It’s a bit more complicated than we thought before. Remember how before, I thought he set up the whole ensemble, all four of the sitters, and then he had them pose while, retreating behind his curtain, he sketched out the whole thing on his glistening wet and reflective canvas, incising the contours with the blunt end of his brush so that his models could take occasional breaks and then return to their positions. But we don’t think it was quite like that anymore. Rather, here, look.” He reached for a superb reproduction of the heartrending painting (see Fig. 43). “Look at Peter’s extended left hand, here on the side, the one closest to us. It’s roughly level with the fruit basket, in terms of depth, yet just about the same size as the fruit basket: those must be mighty tiny apples and positively minuscule grapes. Now, look at Peter’s other hand, flung deep into the backdrop of the painting: it’s the same size as the one closest to us—in fact if anything even bigger, and bigger certainly than Jesus’s hand, which in turn is thrust way forward. Before, we used to think he must have been using some kind of telephoto lens. But no, this is what he did, we did the experiment.” Hockney nodded over at his pastiche. “The lens stayed in place, but he posed the figures separately, one at a time. First, let’s say, Peter. He moved his easel over so that the cast projection was falling on the canvas’s right side. He had his model pose with his hands outthrust, and first he sketched in the hand closest to us, but the rest of the guy’s body went out of focus. So when he’d finished with those notations, he had the sitter move forward, so that his head and torso fell into the sweet spot of the focus, adjusting the easel accordingly; and finally he had him move forward one more time, so that he could get the back hand which, being in the same sweet spot, was the same size as the front one. Note how Peter’s gaze actually seems to fall on nothing—he’s not making eye contact with a Jesus who literally wasn’t there at the time he was painted. Okay, so now Caravaggio moved the easel again, so that the sweet spot fell on the center of the canvas, and he had the Jesus model sit in pretty much the same place and now he did him. After which, moving the easel again, he did the two other figures, one by one. Notice, by the way, the white tablecloth over the Persian rug. That solved the Lotto problem—and you’ll notice by the way the same strategy being used by all sorts of artists around that time. You’ll also notice,” Hockney was now regarding his own pastiche, “this way you could even use the same models over and over again.”

It occurred to me that in a sense Hockney had refined his Ze‹relli analogy yet further. Caravaggio had effectively built up his story through a series of close-ups and reaction shots. “Exactly” Hockney agreed. “For the people of those times, such paintings were motion pictures—their eyes were invited to move through the unfolding story.”

It also struck me that this more supple version of the theory bore to the original version something of the relationship that Hockney’s gridlike Polaroid collages bore to their more fluid and dynamic Pentax successors. For that matter, the entire theory had the feel of a lens being dragged across a vast swath of history as one detail after another fell into its sweet spot.

“This is what we now think happened,” Hockney was holding forth, summing up. “It begins with the concave mirrors, most likely in Bruges around 1425 and spreading outward, but curved mirrors have got this problem: they can only project a zone of focus of about thirty centimeters diameter. Presently artists begin to notice that you can get the same and an even better effect with a lens, and that lenses are much more versatile. Della Porta is describing lenses projecting images through a hole into a darkened chamber as early as 1558. From 1570 or so till about 1660, we enter the era of the left-handed sitters—suddenly you see them everywhere, everybody’s drinking or signaling or grabbing their swords with their left hands (you even get left-handed monkeys!), which is because the lens, unlike the mirror, not only turns the image upside down but reverses right and left. And the artists aren’t able to compensate for that until flat mirrors become affordable, toward the last half of the seventeenth century. After that, artists become more and more adept, the lenses more and more sophisticated—Vermeer, Velázquez, and so on—and new variations arise (Reynolds’s secret camera obscura that could collapse into the shape of a book and, thus disguised, be slotted onto a shelf; Ingres’s camera lucida), up through the invention of chemical photography itself in 1839. “Of course,” he said, “that still leaves us with the problem of Brunelleschi.”

Brunelleschi: a Florentine contemporary of Van Eyck’s, widely regarded as the progenitor, actually about a decade prior to Van Eyck’s breakthroughs, of classic Italian mathematical abstract perspective. The story of that astonishing innovation is one of the chestnuts of art history: how Brunelleschi—who would go on, as his greatest achievement, to mastermind the dome over the Florence cathedral—had earlier in his career contrived a spectacularly realistic pair of paintings, one of the octagonal Baptistery as seen across the square from the cathedral’s deep portal, the other of the view across another nearby square. Both of these panels have since been lost, but their reputation lives on. So precise were they said to have been that Brunelleschi was able to bore a hole through the center of each of the panels and then have viewers stand precisely where he had stood in making them, bring the back side of the panel up to their faces, peer through the hole at the actual scene, and then extend a flat mirror at arm’s length so they could gaze on the reflection of the painted panel itself—and there was no difference!

Hockney and Graves had long been wondering about those panels and that epiphanous moment. How would anyone who had never seen photos or optical projections of any sort ever have come up with the idea for one- or two-point perspective or any other system of mathematical abstraction? There are no medieval antecedents, and understandably so: We don’t ordinarily suddenly find ourselves standing stock-still, storklike, closing one eye and freezing the other in its gaze, in order to gauge a scene. Rather (as cognitive psychologists have recently been showing ever more emphatically) vision as it is lived involves a stereoscopic vantage in continual motion, with the perceiving mind actively engaged in retrieving memory, projecting expectation, computing relative scales, compensating for seeming discrepancies, and so forth. How would the idea of doing it any other way ever have arisen?

The standard account (for example in Martin Kemp’s Science and Art) has Brunelleschi extrapolating from the surveying skills and arts he had been perfecting in his ongoing study of antique ruins. But Hockney and Graves began to suspect that Brunelleschi himself had used an optical device, perhaps even a concave mirror. (Admittedly, were this the case, it might require a rethinking of the puta- tive Bruges-to-Florence trajectory, though perhaps still with the Medici banker Arnolfini as the carrier.) In corroboration, Graves had dug up a remarkably suggestive description of a curved mirror being used to cast an image onto a wall “of things outside not in sight” in a text written in 1275 (!) by the Polish monk Witelo, who in turn seems to have based his hermetic suggestions on the writings of Roger Bacon and, before him, that eleventh-century Arab scholar Alhazan. Graves was also able to build up a fairly strong case for the simultaneous presence of Witelo manuscripts at the turn of the fifteenth century in libraries in both Florence and Ghent. Might not Brunelleschi and Van Eyck, omnivorously curious as both of them obviously were, have separately come upon the same reference? Thanks to contemporary accounts, we know that Brunelleschi staged his demonstration, particularly of the Baptistery panel, early in the morning; that he stood a few feet inside the darkened cathedral portal, facing out into the bright morning light, and that the panel he created was approximately thirty centimeters in length (precisely the dimension of a mirror projection’s sweet spot). Mightn’t he have used a mirror to make the image in the first place and then, instead of moving the lens around as the Flemish took to doing, mightn’t he or his successors have noticed the way the three-dimensional world’s parallel lines seemed, on the two-dimensional panel, to recede to specific vanishing points, and then gone ahead and extended those imaginary lines to create a mathematical perspective (as an alternative to the multiple-vantage method with all its attendant splicing problems)?

Hockney became more and more convinced that this was indeed the case. In late May, on the occasion of a gathering in Florence of scientists and historians exploring scientific issues in Italian Renaissance art, with both Spike and Kemp in attendance, Hockney arranged to have the cathedral’s portals swung open at seven in the morning (a highly unorthodox procedure, for which he’d had to secure special ecclesiastical dispensation) so he could demonstrate what he thought Brunelleschi did. And it worked.

What its “working” meant was open to debate. This time he even left the normally enthusiastic Kemp somewhat cold (Kemp had devoted an entire appendix in his Science and Art to his more orthodox account, based on surveying): This was all just too speculative. “David sees the optical evidence everywhere,” Spike, for his part, subsequently commented to me, “and that may be a problem. He at- tempts to explain too much. Caravaggio’s Bacchus being left-handed, for example: that could have had an optical genesis, but it also might just be an iconographic decision, the left hand being thought of as notoriously lascivious. David leaves too many threads for the naysayers. And yet the overall thrust of his argument is quite powerful.”

Spike’s critique reminded me of an account I’d once heard of the nature of heresy in the Early Christian church—how a heresy in those days wasn’t so much false in itself as an excavation of a long-suppressed aspect of the Truth which was then raised to the level of the Whole Truth and idolatrized as such. The trouble with such heresies (and one could easily substitute all manner of subsequent ones—the feminist heresy, the Afrocentric heresy, the Serbocentric heresy, and so forth, and maybe Hockney’s as well) wasn’t so much one of verity as one of proportion and right relation. (Another art historian once commented to me how she’d have thought that an artist of all people would have been the most suspicious of a Theory of Everything.)

But Hockney’s a real shape-shifter in this regard. Suddenly he’ll seem to double back: “It’s not that everybody was necessarily using optical devices all the time,” he commented to me that day beside his optical tent. “Rubens, Rembrandt, Titian, they often seem to be eyeballing things, whereas even those who clearly are using such devices may not be relying on them at every moment. But the devices established a standard, they dictated a look. In fact,” he gestured back into the tent where the tumble of satin was still glowing on the blank canvas, “to see it was to use it. You see how overwhelmed everybody is by the sheer beauty of such projections even today—and we live in a world surrounded by movies and magazines and television. Imagine the impression that sort of projection must have made on them! And these were visually intelligent people; looking was what they did for a living. Surely they would have seen the implications. How convincingly a three-dimensional space could be laid across a two-dimensional plane. You think they would have thought twice about using it? And even if they themselves did, with everybody else using it, the optical look would have spread everywhere because they’d all have been studying each other’s efforts.”

In the meantime, I’ve been beginning to notice a subtle shift in the sorts of objections to Hockney’s theory that I’ve been hearing. In the earliest days, when I’d broach the theory with an art historian or a curator, I’d encounter the old bird-talking-back-to-the-ornithologist problem: What standing did a mere artist have even to be entering such charged and protected terrain? (All professions, as someone once said, are to a certain extent a conspiracy against the laity.) Hockney’s speculations would be dismissed out of hand—not true, impossible, where’s the documentary evidence, where are the written accounts or instruction manuals or references in ledgers and so forth? More recently, skeptical response has segued into variations on “Well, we knew that all along.” Or somewhat more subtly, “But who cares how they made the paintings—that’s not what matters. What matters is iconography, social context, market relations, the metahistory of representation”—whatever.

Hockney has been countering that the story of how artists saw and extended the possibilities of seeing is inherently fascinating, in and of itself. But in the end, that’s not been his main concern. In the same way that during the early eighties, when he was taking literally hundreds of thousands of snaps across his photocollage passion, the celebration of photography itself had never been Hockney’s principal intention (in fact the whole passion was being conducted as a massive critique of the claims of photography)—so, more recently, for all his immersion into the techniques and triumphs of the old masters, celebrating their optical achievement has never been his principal focus. How they made their paintings—the four-hundred-year optical hegemony over painting—matters to Hockney primarily because of what came after: his true passion has been the post-1839 assault on the optical waged by his real heroes—Manet, Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Picasso, artists who through great struggle threw off the cyclopean way of seeing and began looking at the world with two eyes, from a more realistically moving and lively vantage.

“Look,” he said to me one day a few months ago as we gazed across the length of his studio at the 1750–1900 expanse of his Wall. “Look at that basket of fruit by Chardin over there on the left, and now at the same subject by Cézanne—see it there on the right ? Chardin’s version, for all its indisputable mastery and beauty, feels far away; it’s a picture of fruit at the far end of an optical remove, receding into the picture, whereas Cézanne’s, even from this far away, feels right up close; those apples feel close at hand, they feel present to hand, they come out to us. That’s what you can achieve when you break from the tyranny of the optical.

FIG 71 William-Adolphe Bouguereau, La Vague, 1901.

“And yet”—he now pulled me back across the room toward that section of the Wall—“for all the modernist achievement in that regard, it was the monocular optical vision that appears nevertheless to have triumphed. Compare those Cézanne bathers there with this Bouguereau nude, an academic work, which in effect continued the optical tradition in painting long after the invention of chemical photography [Fig. 71]. You can just see how Bouguereau was using projected photographs: the breaking wave is an entirely artificial backdrop, ludicrously unintegrated with the figure in the foreground, a flat; you can even make out the table the model must have been sitting on in the indentations of the sand. But this is the view that won and continues to hold sway to this day, in photojournalism, in advertising, on television (which is one great receding perceptual tunnel), in movies. David Graves came upon a great line in one of those thirteenth-century precursor texts he’s been digging up, Arnold of Villanova’s advocacy of secrecy about emerging esoterica: ‘Some of this knowledge should not fall into the hands of showmen and fools.’ Quite something to come upon,” he laughed, “here in Hollywood on the far side of the millennium.”

One morning I rose to find another of Hockney’s occasional faxes dangling out from my machine. He’d photocopied two printed texts onto a page. The first, in boldface, read:

4. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in Heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water underneath the earth;

and the second:

Islam tells us that on the unappealable Day of Judgment, all who have perpetrated images of living things will reawaken with their works, and will be offered to blow life into them, and they will fail, and they and their works will be cast into the fires of punishment.

Beneath these unsettling edicts, Hockney had scrawled:

I will try to send some better news later.

For all the humor of his dispatch, there’s no question that Hockney feels he is playing for big stakes—that more, at any rate, is up for grabs than a mere reinterpretation of the history of painting. Falco, for his part, has been pushing his researches into almost revolutionary territory. He is convinced that his collaboration with Hockney has been leading him toward an entirely new way of conceiving the problem of computerized visual analysis, one of the holy grails of artificial intelligence research. So now he has yet something else to do on those mornings when he’s not monkeying around with his bikes out in the garage.

The other day, reviewing my files as I prepared to write this piece, I happened upon a handwritten note Hockney had faxed me roughly midway through the adventure, when the stakes were beginning to come clear to him:

Dear Ren:

We move on, we have begun to understand the construction of the Van Eyck altar pieces—Dirk Boutes, Rogier van de Weyden, etc. It’s not one window—like Alberti’s perspective, but many windows—more like the Polaroids.

Nevertheless, this is not just about Art History—nor about artists “cheating,” although we had in the process of all this to understand the use of optics.