The Beagle dropped anchor in Falmouth, England, on October 2, 1836. On her voyage of 58 months, 43 had been spent in South America. From Peru, she had sailed home in just 13 months, all aboard her ready to be done with the voyage, their thoughts fastened upon England and home.

Darwin, who had been seasick through one last gale in the Bay of Biscay as the Beagle worked her way up to the Western Approaches, was packed and thoroughly ready. He disembarked at once. That night (“a dreadfully stormy one”) he started north from Falmouth by mail coach to Shrewsbury and reached The Mount, the Darwin family home, at breakfast time on Wednesday, October 5.

“Why, the shape of his head is quite altered,” said his father to Darwin’s gaping sisters. Though neither Darwin nor his father were adherents of phrenology, both seemed to have believed, as FitzRoy did about his Fuegians, that concentration and employment of mental powers could affect the shape of the cranium. Darwin cites this observation by his father, “the most acute observer whom I ever saw,” as evidence that “my mind became developed through my pursuits during the voyage.” In fact, Darwin was balding prematurely. While away at sea he had lost most of the hair on top of his head.

The Beagle was an instant dockside attraction. In Falmouth, newspapers announced her arrival from around the world. People crowded the quays to see her, board her, put their hands upon her as they would today the space shuttle, and to question her crew about storms and savages. Her captain’s company was eagerly sought. On October 3, the day after her arrival, FitzRoy was invited to the home of Robert Were Fox, Falmouth’s eminent Quaker scientist. His daughter, Caroline Fox, recorded the visit in her journal.

October 3.—Captain FitzRoy came to tea. He returned yesterday from a five years’ voyage, in HMS Beagle, of scientific research round the world, and is going to write a book. He came to see papa’s dipping needle deflector, with which he was highly delighted…. He stayed till after eleven, and is a most agreeable, gentlemanlike young man. He has had a delightful voyage, and made many discoveries, as there were several scientific men on board.

The Beagle sailed on to Plymouth and Portsmouth to receive visits from Admiralty bigwigs, “repectable-looking people,” (who came aboard by the accommodation ladder) and “others” (humbler sightseers who were permitted to climb into the ship on a rough plank).

Darwin wrote to FitzRoy from Shrewsbury, offering sympathy at finding himself once more in “that horrid Plymouth,” where he had languished for so many months before beginning the voyage. But the time had been well spent for FitzRoy, as he revealed in his reply to Darwin.

Dearest Philos…that horrid place contains a treasure to me which even you were ignorant of!! Now guess and think and guess again. Believe it, or not,—the news is true—I am going to be married!!!!!! to Mary O’Brien. Now you may know that I had decided on this step, long, very long ago. All is settled and we shall be married in December.

On top of all the anxieties FitzRoy had suffered through his mission, there had been the question many seamen take with them when they leave a loved one at home: Will she still be there?

The Beagle sailed on up the Channel and into the Thames to Greenwich, where she let go her anchor on the zero meridian and FitzRoy made his final observations of the voyage. The ship remained at Greenwich for two and a half weeks for visits by the Astronomer Royal and other guests, then dropped downstream on the tide to Woolwich Dockyard, where she had been built and launched sixteen years before. On November 17 the ship decommissioned, her crew paid off.

Many of the seamen and officers who left the ship and parted from one another had been aboard the Beagle on both her voyages, under FitzRoy’s command for more than six years. They had faced something very like war during those years; together they had fought the sea, the Fuegians, and the most ferocious weather on Earth, and many times they had saved one another’s lives. A few of their number had died. FitzRoy did not write about it, but disbanding beside the Beagle on the dock in Woolwich that day would have been as emotional and wrenching for those seamen as the breakup of a tight battalion of long-serving soldiers at the end of a world war. The men went home, or they found berths aboard other ships. Some of the officers went on to notable careers. Most of the crew simply disappear from record.

FitzRoy went home to Onslow Square in London to prepare for his wedding and begin the work of overseeing the drawing and production of new, wonderfully accurate nautical charts from his years of prodigious surveying.

Darwin felt awkward at home. He had left as a boy just graduated from university and come back a grown man, an adventurer, a working scientist. He’d spent years galloping around South America with gauchos and soldiers, eating wild animals over camp fires, trading with natives, roaming through jungles, sharing desperate adventures with tough seamen.

The Mount was filled with sisters. They fussed over him. They expected him now to stay at home and settle into life as a country gentleman, to pick up again the threads of his preparation to be a country parson. But Darwin had been around the world, and while travel no longer held any attraction, the disciplines of the natural sciences, in which he had steeped himself for five years, and the community of his fellow scientists, now beckoned and urged him on to new exploration. He could not go home again.

Towards the close of our voyage I received a letter whilst at Ascension [Island], in which my sisters told me that Sedgwick had called on my father and said that I should take a place among the leading scientific men. I could not at the time understand how he could have learnt anything of my proceedings, but I heard (I believe afterwards) that Henslow had read some of the letters which I wrote to him before the Philosophical Soc. of Cambridge and had printed them for private distribution. My collection of fossil bones, which had been sent to Henslow, also excited considerable attention among palæontologists. After reading this letter I clambered over the mountains of Ascension with a bounding step and made the volcanic rocks resound under my geological hammer!

Darwin came home to the fruit of his tremendous industry over the course of the last five years. His collection amounted to a full museum’s worth of the world’s natural marvels: whole groups of plants and insects, birds, small and large animals and reptiles, corals, shellfish and other sea creatures and invertebrates, bones, fossils, rocks, and minerals. His labeling, cataloging, wrapping, drying, and bottling of specimens had been meticulous and thorough.

Everything had gone to Darwin’s mentor, Professor Henslow in Cambridge, who unpacked each box and crate on arrival, checked its condition and need for further preservation, and stored it for Darwin’s return. Henslow had been unable to resist putting out word of the magnificent collection accumulating, or publishing extracts of Darwin’s letters to him. He had spent five years paving the way for Darwin’s reappearance, so that in the world of the professors and the burgeoning natural sciences, Darwin was already famous. Charles Lyell wanted to meet him, the Geological Society wanted to elect him a Fellow. Museums everywhere wanted his bones and butterflies. There was no going back, no more search for a career. He had become somebody. All that running away from his studies—beetle collecting, riding, hunting, and shooting—had found him a destiny.

After ten days at home, he escaped to London, to stay with his older brother Erasmus. His life there became frantic with activity—tea parties with the Lyells, irresistible invitations from leading scientists. In December he moved to Cambridge, to the site of his collection. There, with the help of his Beagle assistant, Syms Covington, he began to look through everything, to unravel his voyage, to see what he had really done.

He sent his specimens off to the experts who could identify them, determine whether he had found new species, give them their official Latin names. Most of the early excitement was naturally generated by the big fossilized bones of the extinct creature Darwin had dug up on the east coast of Patagonia, the Megatherium—or was it a Scelidotherium, or a Toxodon, or all three? Here was something tangible to wonder at, obviously destined for the museums already clamoring for them. The smaller stuff—the Galapagos birds with their varying sizes of beaks, the different shells of the tortoises—were of subtler interest, and it would be some time before Darwin began to cogitate on just why they varied.

He had a book to write. Late in the voyage, while FitzRoy was beginning to prepare and collate his own journals for publication, he asked Darwin if he could read some of what he had been writing in his journals. FitzRoy thought “Philos’s” observations good enough to incorporate into the long narrative of the Beagle’s two voyages he was planning to publish. Initially, both Darwin and FitzRoy saw this contribution as sections slipped into the larger work, but later the size and readability of Darwin’s diary led them both to believe it could form a distinct volume on the natural history of the countries the ship had visited. Out at sea, at the time of FitzRoy’s suggestion, Darwin was flattered, excited by the idea of another book to write (in addition to the book on the geology of the counties visited, which he had first conceived early in the voyage at the Cape Verde Islands). But by late 1836, surrounded by overflowing crates of specimens in Cambridge, his head filled with a kaleidescope of images and ideas, such a book had become a mounting imperative to him. Threads and shapes and anomalies of creation were coursing through Darwin’s brain, hot-wiring his synapses, and he felt an urgent need to make sense of it all.

Such a book would also, he knew from the attention he was getting, put him on the map in the scientific community. This was what he wanted now, to take his place, as Sedgwick had suggested, among the leading scientists of the day, men like Lyell, whom Darwin respected and admired hugely, who influenced the thinking of the civilized world. He wanted to be one of them. A book about his voyage would do it.

Darwin began writing it in Cambridge in January 1837. In March, with most of his collection dispersed to the experts for identification, he moved back to London, renting rooms in Great Marlborough Street for himself and Covington who was still working as his general assistant. There he continued work on his book. It closely followed the daily journal he had kept throughout the voyage, on land and sea.

FitzRoy was at least as busy. After his marriage, he and his wife settled into domestic life in London, and Mary was soon pregnant.

FitzRoy returned to accolades rare for a naval officer in peacetime. He was publically thanked in Parliament. The Royal Geographic Society presented him with their gold medal. The appreciation of the Admiralty—for him more important than any honor—was deep. The quality of his work as a marine surveyor was immediately evident. It was so thorough and accurate that the resulting charts were used for more than a century.

In aristocratic, social, and scientific circles, FitzRoy was famous—much more so than Darwin, whose renown was narrowly confined to the community of academics and naturalists. On his return to London FitzRoy was much sought after: a dashing, witty, charming officer, a gentleman, seaman, and scientist of extraordinary accomplishments, with equally extraordinary tales to tell. More than anything, he had sailed around the world, and the neat geometry of this feat provided the shape and allure to all he had done. He was England’s nineteenth-century astronaut returned to Earth. Everyone wanted to meet and talk with Captain Robert FitzRoy.

When his work on his surveys and charts was completed, FitzRoy didn’t seek another sailing commission. Despite the inroads he had made in his personal fortune he was still financially independent, and with Mary pregnant and his own book of the voyage to write, he had more than enough to keep him at home.

The narrative he had long planned to publish consisted of two main parts. A first volume would cover the voyages of the Adventure and the Beagle during the years 1826–1830 (with Pringle Stokes and FitzRoy as successive captains of the Beagle), when both ships had been under the overall command of Captain Phillip Parker King; a second volume for the Beagle’s five-year voyage, from 1831 to 1836. Volume One was to be authored by Captain King, but as he had moved to Australia, the production of this fell entirely to FitzRoy, who had to put together and edit the first book from his own, Stokes’s, and King’s thick pile of notes and logs.

Volume Two, FitzRoy’s own dense day-by-day account of the second voyage, was enormous, if not quite epic. With lengthy essays on the state of native peoples, descriptions of coastlines, weather, sea conditions, shiphandling, adventures ashore, and, not least, the repatriation of the Fuegians, it would run to 695 pages and a quarter of a million words when completed. Multiple appendixes covered 350 pages in a separate volume. Darwin’s book would form a third volume, but apart from that it was all FitzRoy’s to do. He began early in 1837.

It must have seemed to him at first an enjoyable task: to stay at home with his wife and coming child, to voyage daily no farther than from bedroom to study. To suffer no setbacks from storms but rather to sit in a peaceful room in England and view the weather from the dry side of a windowpane—to a seaman such a secure berth holds an intense appreciation. To be free of the bedevilment of hostile natives. To light a fire, trim a wick, and spread around him at his desk the notebooks, logbooks, maps, and drawings from which he could select and produce a coherent account; to draw up a good chair, dip a smooth nib into a still inkwell, and begin.

He was swamped. Deciphering the handwritten logs of two other men, King and Stokes, going over their every word, checking each estimation of time or distance for mistakes or inconsistencies—it would be their accounts but his name would testify to it all—proved the most serious drudgery. This was not writing, not the creative effort that returns some glow of satisfaction for long hours in a chair.

He dined out, spent time with Mary and his new daughter, took walks—from his house in Onslow Square, which faced a garden, it was a ten-minute stroll to the Royal Geographic Society, or Hyde Park, a short cab ride from Admiralty House, Whitehall, Mayfair, or his club in St. James—but always the enormity of the work to be done gnawed in his mind and pulled him back to his study. It pulled him out of sleep with a jolt in the predawn hours, and it kept him bent over his desk late into the night. The two volumes, and a third comprised of essays and appendixes, amounted to 1,650 pages and over half a million words (six times the size of this book), and none of it could be done by anybody else. He still had his servant from the Beagle, Fuller, whom he’d recruited to be his clerk after Hellyer’s death, to assist him, to run errands, to help arrange for the engravings of plates for illustrations, but no assistant or clerk could check what only FitzRoy knew. The work pulled FitzRoy’s high tension wires tighter.

He and Darwin saw each other rarely after the voyage. Even when both were living in London, they seemed to grow farther apart.

I saw FitzRoy only occasionally after our return home [Darwin wrote many years later], for I was always afraid of unintentionally offending him, and did so once, almost beyond mutual reconciliation.

In the spring of 1837, Darwin came to tea with the FitzRoys. “So very beautiful & religious a lady,” he thought Mrs. FitzRoy. But the visit was probably less for social reasons than to confer about specimens both had taken from the Galapagos Islands: Darwin needed FitzRoy’s help to identify his birds.

It was not a happy reunion. Darwin came away bristling over FitzRoy’s ill humor, firing off several letters about his former messmate.

The Captain is going on very well [he wrote to his sister],—that is for a man, who has the most consummate skill in looking at everything & every body in a perverted manner.

And he wrote to Charles Lyell, with whom he had now become close friends.

I never cease wondering at his character, so full of good & generous traits but spoiled by such an unlucky temper.—Some part of his brain wants mending: nothing else will account for his manner of viewing things.

Nevertheless, FitzRoy gave him what he asked for.

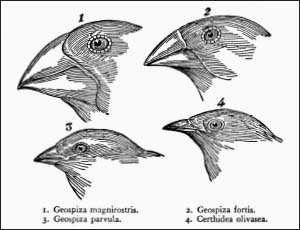

Darwin had sent his bird, mammal, reptile, and insect specimens to the London Zoological Society for identification. One of its fellows, John Gould, undertook the classification of his birds. Gould was a widely respected ornithologist and taxonomist, so Darwin had to believe what Gould told him about his Galapagos collection: three mockingbirds Darwin had collected from three different islands were not variations of South American birds but three new and distinct species. A number of birds Darwin had labeled variously as finches, wrens, and blackbirds, were all finches, Gould claimed, of a new group unknown beyond the Galapagos Islands. Their very different beaks made them finches of different species, and Gould believed that, like the mockingbirds, each species came from a different island.

Or so it appeared, but here Darwin’s collecting had been uncharacteristically clumsy. He had commingled specimens from several islands, never imagining that different but identical islands, not far apart, might produce different birds. Gould needed more Galapagos finches, properly labeled. Darwin could hardly return to the Pacific, so he had approached FitzRoy to borrow birds the captain, his assistant Fuller, and various seamen had clubbed and taken away from the islands, which FitzRoy had already presented to the British Museum. Despite their quarrel over tea, FitzRoy had two sets of bird skins sent to Darwin. Syms Covington had his own four birds from the Galapagos. All these were examined by Darwin and Gould and compared with Darwin’s lists and catalogs, in an effort to confirm what Gould claimed: different islands, different species.

One genus; different species. The finches with varying beaks that Darwin found at the Galapagos Islands. (Narrative of HMS Adventure and Beagle, by Robert FitzRoy)

Another fellow from the Royal Zoological Society, Thomas Bell, who had been identifying Darwin’s reptiles, came back with a parallel conclusion: each island of the Galapagos chain had produced its own distinct species of iguana lizard.

Darwin received this news in the spring of 1837 while he was deep in the writing of his book about the voyage. It concurred with a remark the islands’ vice governor had made to him while he was there eighteen months earlier, something about the markings on the shells of the islands’ tortoises. He hadn’t taken much notice at the time, but now the memory of it pealed through his mind. He put it all together in his chapter on the Galapagos Islands.

By far the most remarkable feature in the natural history of this archipelago [is] that the different islands to a considerable extent are inhabited by a different set of beings. My attention was first called to this fact by the Vice-Governor, Mr Lawson, declaring that the tortoises differed from the different islands, and that he could with certainty tell from which island any one was brought. I did not for some time pay sufficient attention to this statement, and I had already partially mingled together the collections from two of the islands. I never dreamed that islands, about 50 or 60 miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted.

On March 14, while Darwin was preoccupied with identifying his finches, he attended a lecture given by Gould at the Zoological Society, on the subject of the South American Rheas, or ostriches, specimens of which Darwin had brought back and presented to the society. In northern Patagonia, ostriches were common. The gauchos who ate them had told Darwin of a similar but much rarer bird they called the Avestruz petiso (“little ostrich”). Darwin had looked for this bird with no success, until farther south, at Port Desire in January 1834, he was eating what he thought was an ostrich, shot by one of the Beagle’s company, when he noticed it was smaller. The meal was over and the bird fully consumed by the time Darwin realized it was an Avestruz petiso. But rooting through the spat-out bones, skin, feathers, and leftovers, he came up with “a very nearly perfect specimen” that was later exhibited at the Zoological Society. But it was not the rarity he had been led to believe.

Among the Patagonian Indians in the Strait of Magellan, we found a half Indian, who had lived some years with the tribe, but had been born in the northern provinces. I asked him if he had ever heard of the Avestruz Petise? He answered by saying, “Why, there are none others in these southern countries.”

Gould did Darwin the honor of naming the smaller, southerly ostrich Rhea darwinii, after the man who had eaten it. The point of his lecture was that the Rhea darwinii was just as common in southern Patagonia as the bigger bird was farther north, yet there were differences enough between the two to classify them as different species. Different places, different birds, though of essentially the same feather. Just like the finches.

Why, Darwin began to wonder, had the creator bothered with such subtle differences? Why not make one species of finch and let it suffice for one small group of islands? Why make a baker’s dozen? Why two ostriches where one would do?

A little over a year earlier, on a sunny afternoon in January 1836, while out hunting kangaroo in New South Wales, Australia, such questions hadn’t troubled him.

I had been lying on a sunny bank & was reflecting on the strange character of the Animals of this country as compared with the rest of the World. An unbeliever in every thing beyond his own reason, might exclaim “Surely two distinct Creators must have been [at] work; their object however has been the same & certainly the end in each case is complete.”—Whilst thus thinking, I observed the conical pitfall of a Lion-ant:—A fly fell in & immediately disappeared; then came a large but unwary Ant; his struggles to escape being very violent, the little jets of sand…were promptly directed against him. His fate however was better than that of the poor fly’s:—Without a doubt this predæcious Larva belongs to the same genus, but to a different species from the European one. Now what would the Disbeliever say to this? Would any two workmen ever hit on so beautiful, so simple & yet so artificial a contrivance? It cannot be thought so.—The one hand has surely worked throughout the universe. A Geologist perhaps would suggest, that the periods of Creation have been distinct & remote the one from the other; that the Creator rested in his labor.

Darwin did not, in January 1836, question why the creator had bothered to make two different versions of the same insect. Like most nineteenth-century scientists and thinkers, he did not question that a creator had been behind it all. Time, he suggested, like a good Lyellian geologist, had simply made the creator rethink his model. It didn’t occur to Darwin then that the place, which after all looked not unlike England, might have something to do with it.

Fourteen months later, however, he was questioning the creator’s efforts. Nevertheless he transcribed this diary entry almost exactly into the book he was writing—his questions had not yet led him to a solid conclusion. (By 1845, when the second, revised, edition of his book was published, that conclusion had come, and Darwin relegated this incident with the lion ant to a footnote, shorn entirely of his ruminations about what a disbeliever might think of the creator’s scheme of things. By then he had become, in his own words, “an unbeliever in every thing beyond his own reason.”)

Darwin’s reasoning brought him to an inescapable idea: perhaps the creator had not created, at the beginning of time—on day five according to the Book of Genesis—all those different finches and placed them on the Galapagos. It seemed more reasonable that the islands might have been populated by South American birds, which, in time, could have adapted to the peculiarities and food sources on each island, until they became so distinctly, consistently different that they had become a new species. The same was possible with the South American ostriches. One species might have evolved from another.

It wasn’t a new idea, and certainly not to Darwin: his own grandfather had been an evolutionist. The Frenchman Lamarck had suggested the same thing almost forty years earlier, but in far more controversial terms: that humans had evolved from apes. Lamarck believed each plant, each animal, contained a “nervous fluid” that enabled it to generate in new directions, adapting to its local environment. The ancestors of giraffes, he suggested, extended their necks over time by stretching to eat the leaves on overhead trees, causing their nervous fluid to flow into their necks which, over successive generations, grew longer. Apes might similarly have dropped to the ground from trees and found that walking or running upright was the more efficient posture.

However clever or reasonable an idea this might have seemed, it was religious heresy. It suggested a godless world propelled by ungoverned, earthly forces. Such an anarchy of creation would produce a nightmare world of incessant haphazard mutation, of gargoyle monsters. And that could not be so, people believed, for the order and beauty of the world was everywhere apparent.

But Darwin saw a middle way: the transforming of one species into another, a process guided by nature, not by God, whereby a plant or animal gradually selected the physical peculiarities best adapted to its environment.

Inescapably with this came the corollary that Adam and Eve were not the semi-angels created by God in the Garden of Eden, but animals descended from other animals, most closely and recently from monkeys. Nothing encouraged this notion more than Darwin’s acquaintance with Fuegians. “Viewing such men, one can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow creatures placed in the same world,” he had written in his voyaging diary.

He had found it difficult to believe that he and they were one species. Bent, hulking, primitive, living in shelters far less complex than a bird’s nest, the Fuegians had seemed to provide a picture of Man at the dawn of his transformation from ape, perhaps closer to the root they had sprung from than to the apotheosis represented by European man. At the Zoological Society in London he had observed an orangutan named Jenny throwing a tantrum when her keeper would not give her an apple.

She threw herself on her back, kicked & cried, precisely like a naughty child.—She then looked very sulky & after two or three fits of pashion, the keeper said, “Jenny if you will stop bawling & be a good girl, I will give you this apple.—” She certainly understood every word of this, &, though like a child, she had great work to stop whining, she at last succeeded, & then got the apple, with which she jumped into a chair & began eating it, with the most contented countenance imaginable.

Remembering the relentless demands of “yammerschooner,” Darwin went home and wrote in his notebook: “Compare the Fuegian & Ourang outang & dare to say difference so great.”

Three years earlier, in Tierra del Fuego, he had written in his diary, “Nature, by making habit omnipotent, has fitted the Fuegian to the climate & productions of his country,” already unconsciously anticipating his new thinking about the “transformism,” as he first thought of it, of species.

He wasn’t afraid of what he was thinking. From all he had seen on his five-year circumnavigation, it made sense. The scientist in him embraced it. However, he was well aware of its religious impropriety. It was after all blasphemy, and Darwin was not a bold man in his researches. But he was conscientious. He had no wish to be controversial, so he kept his musings to himself. That summer of 1837 he started scribbling in notebooks, jotting down and organizing such thoughts. It would be twenty-two years before he published his ideas about transmutation, and then he did so only because another naturalist, a malaria-ridden Englishman wandering through Borneo, shocked him into action by sending him a letter suggesting identical conclusions.

Darwin finished his account of the voyage in September 1837, after nine months of concentrated transcription and editing of his own journals. It contained no allusion to his ideas on the transmutation of species. It was simply a fabulously adventurous travel book, filled with the descriptions of a teeming natural world by a remarkably observant scientist. There was nothing in it to offend anybody. He sent it off to the publisher, Henry Colburn, whose office was conveniently close by, on Great Marlborough Street in London where Darwin himself was living. The finished narrative, to be included with the three volumes FitzRoy was preparing, was due to be published the following year, 1838, but Colburn’s inquiries to FitzRoy about the date of his completion met with evasion.

FitzRoy was desperately trying to pull together a mass of chronologically overlapping, generally uninspiring seafaring accounts by three different authors into some sort of readable shape. He was brittle and ready to snap.

He finally did so when Darwin sent him the preface to his account in November.

FitzRoy reacted to it with a cold fury. Darwin’s preface, he wrote back to him, showed a shameful lack of acknowledgment of all those aboard the Beagle—not only the captain himself but the ship’s officers—who had tirelessly and generously assisted Darwin, looked after him, gave up room for him, put his well-being before their own on all occasions, and generally made possible all his efforts throughout the voyage, and of course, subsequently, the publication of his book. FitzRoy was right. Darwin had offered little thanks to the men who had nursed him through seasickness and looked after him as a favored guest for five years. There was no distinction made between Beaufort’s kindness in allowing Darwin to go on the voyage and FitzRoy’s unbounded generosity to him both as a guest and with the facilities of the Admiralty in shipping home his collection.

Darwin apologized. He rewrote his preface in more generous terms.

But there was more than slighting acknowledgment and offended feelings to their growing estrangement. Something else was happening to drive the two men irreconcilably far apart. Within two years of returning to England, both experienced profound changes of thought that were in direct and contentious opposition.

While Darwin was moving ineluctably toward scientific enlightenment, FitzRoy was heading fast in the other direction.