•

Robert Bauval caused a sensation when, together with Adrian Gilbert, he wrote The Orion Mystery back in 1994, which claimed that the Giza pyramids were planned as a representation of the stars of Orion’s Belt. It seems a reasonable enough claim, given that it is known that these stars were important to the pyramid builders, but virtually since the day it was written Egyptologists have been up in arms to dismiss it in favour of their own pet theories.

Robert may not walk like an Egyptian, but he certainly thinks like one, being born and brought up in Alexandria to parents of Belgian origin. He is a fluent Arabic speaker and has spent most of his life living and working in the Middle East and Africa as a construction engineer.

We decided that we needed to share our findings with Robert, who we knew had for some time lived in southern England. However, we soon found that he had left the country, having had the good fortune to sell his house just as the credit-crunch of 2008 hit the Western world. He was obviously missing the warmer climes of his youth in Alexandria as he had now taken an apartment on the Costa del Sol in southern Spain. By some coincidence Robert’s new residence was just a 15-minute drive from a house Chris has as a holiday home, so it was a simple matter to arrange a convenient date and time for a meeting.

We left England early on a very icy January morning and arrived less than three hours later to the pleasantly warm city of Malaga. Without hold baggage we picked up our hire car without delay and headed out on our 30-km journey down the motorway signposted to Cadiz. After calling at the local supermarket for some essential supplies we were soon sitting by the swimming pool in hot sunshine planning how best to introduce Robert Bauval to our discoveries.

We arrived at Robert’s home early the next day. It was a delightful apartment in a high building that gave him a fantastic panoramic view of the Mediterranean. In the first few hours we talked about many things and Chris was surprised to hear that a friend of his had visited Robert and his wife the previous evening. This was the American novelist, Katherine Neville. A few years earlier Chris had enjoyed a memorable dinner with Katherine and her husband, Professor Karl Pribram, the award-winning medical academic and neurosurgeon. The conversation had been delightfully varied, extending from the motive behind the fall of the Knights Templar to Karl’s latest researches into the quantum state of the Bose-Einstein condensate elements within the human brain.

We could only hope that today’s discussion was going to be as much fun – but hopefully less complicated!

Robert had invited his elder brother, John Paul, to join us. John Paul is an architect and has lived in this part of Spain for 45 years. He has been a major force in its development as a tourist location. But he is also a talented amateur mathematician, who was keen to hear more of the metrological properties underlying our findings.

Our meeting with Robert was going well. Both Robert and John Paul were excited about our discoveries, and Robert was finding powerful connections with his own recent researches. Both brothers immediately saw the logic of the 366-degree circle arising from the Earth’s axial spins per solar orbit. But when we discussed the 233-732 relationship used at Thornborough to produce a circle with a circumference of 2 × 366 equal units, Robert raised his hand in the air, as though calling for a pause in the conversation.

‘These numbers – 732 arising from double 366 with 233 and pi. We have also found these in Egypt – firstly at Saqqara by Jean-Philppe Lauer,’ Robert said, as he looked down at the plans of the British henges. He jumped up and retrieved a copy of his book, The Egypt Code, from his bookshelves. He flicked through the pages and pressed the book flat before passing it for us to see

The Saqqara pyramids are a few kilometres south of the Giza Plateau and some decades older. On a plan of the boundary wall Lauer had identified that the northern and southern walls of the boundary wall of the Djoser complex each had 2 × 366 panels. At first glance it appeared to be a ceremonial acknowledgement of a ‘magical’ number pattern rather than a practical application for astronomical purposes. But nonetheless, it was obvious that someone in Egypt knew about the importance of these values 100 years or so before the Giza trio were planned! This was getting very interesting.

After several hours of conversation we set out to walk to a fish restaurant, some 3 km along the beach, to continue our wide-ranging discussion. The sun shone with the power of a good English summer’s day, and the food was as good as the conversation. We continued talking as the sun fell lower across the sea.

As we walked back to Robert’s apartment, we wondered what he would make of hearing a new take on his famous Orion correlation theory. He might love it but, then again we were well aware that he might not.

Without doubt Robert Bauval is ‘master of the Giza Plateau’ and one does not lightly tell him that he might be wrong. So we didn’t attempt to. But we did show him an argument for considering one significant adjustment to his famous theory.

What we had found was based on our discovery that ancient cultures measured stars by timing their relative movements with pendulums. It seems that nobody, including Robert, had ever given a great deal of thought to how the pyramid builders of Giza had measured the relative position of the stars in order to map them so accurately onto the ground. It appears that most commentators have simply assumed the builders did it by looking upwards to gain a mental impression of the star group and then drawing the arrangement on a sheet of papyrus or a slate before evolving their awesome ground plan through artistic interpretation alone.

In our opinion this simply would not work, or rather it would not work to the level of accuracy we knew existed in terms of the Giza pyramids and Orion’s Belt.

Our years of work on prehistoric and ancient metrology had already taught us to respect these long-gone builders as true engineers, rather than casual artists. The magnificent quality of the Thornborough and Giza layouts screams out that there was heavy-duty science behind their unerring accuracy.

Because stars as seen in the night sky are little more than ‘pin pricks’ of light, any two stars can be compared with any two objects on the ground at any arbitrary scale. But when three stars are compared to three terrestrial objects, unless there is a flawless fit, one has to decide which two are correct (as two always will be) so that the degree of inaccuracy for the placement of the third can be established. The standard way of comparing the three main Giza pyramids with the shape of the stars of Orion’s Belt, both by Robert and his critics, is to consider Khufu’s and Khafre’s pyramids as being the ‘correct’ ones and then arguing a smallish error in the placing of Menkaure’s pyramid (the southernmost and by far the smallest of the three).

We are as certain as it is possible to be that this is not a correct assumption. Because the tool employed was the pendulum, and because we know from our findings at Thornborough and elsewhere that distances on the ground were direct translations of time in the sky, we knew that the outer two pyramids (Khafre and Menkaure) had to be positioned first and then the central pyramid of Khufu fitted in last.

This is because, as described in Chapter 6, the period of time between the outer stars of Mintaka and Alnitak reaching a fixed point was measured in seconds as they rose above the horizon, which can then be translated into the same number of any units of length. The gap between the first and second, and the second and third, was gauged when the Orion’s Belt trio were level with the horizon (at their maximum altitude – exactly south). However, whilst the ancient observers could accurately gauge the ‘off-centredness’ of the middle star in horizontal terms, there was no way they could measure its vertical deviation from the straight line between the other two stars.

This one element could only be estimated by eye alone.

We would therefore expect these perfectionist pyramid-engineers to get every aspect of the ground plan extremely accurate – apart from the amount of deviation of Khafre’s pyramid to emulate the dogleg shape of the stars they were copying. The builders knew the precise point on the SW–NE ‘back sight’ line to place the middle pyramid, but not the 90-degree offset towards the northwest.

We would therefore expect to find some level of error to be present on the ground plan in relation to this aspect – and this aspect alone. This is exactly what we found when we made a slight twist in the logic of Robert’s Orion correlation theory.

Our meeting with Robert and John Paul had been wonderfully exhilarating and stimulating. But now we were to introduce the idea that we believed needed to be aired. It does not form any part of our core thesis – but we still had to share it.

We put it to Robert that maybe there was a different way of looking at the Giza ground plan in the light of this one expected error. And, we suggested, it was a solution that fitted all of the available facts even better than anything discussed before.

We had been sitting in the bar of our hotel in Giza, some months earlier, drinking ice-cold Egyptian beer whilst looking straight up at Khafre’s pyramid, when the idea began to develop. On that same day we had taken a long and close look at the reassembled pyramid boat housed near the Great Pyramid, and it seemed to us that the importance of this vessel, and of others like it, might have been underestimated by earlier Egyptologists.

Seven boat pits have been found in the whole complex of Khufu at Giza, two of which are associated with the lesser so-called Queen’s Pyramids. These boat pits are very large – over 50 m long, 7 m wide and nearly 4 m deep. Whilst some of the pits have been found to be empty, two intact boats were discovered in 1954 by the young Egyptian archaeologist Kamal el-Mallakh. When one of the slabs was raised from the eastern pit, the planking of the great boat was seen – it had been dismantled and carefully flat-packed four and a half millennia before. One of these Lebanese cedar boats had its 1,224 individual parts reassembled by Ahmed Youssef Mustafa during a period of some 10 years, and is now on display in a superb boat-shaped museum next to the Great Pyramid.

In the absence of any ancient written records about these vessels, scholars have speculated about their purpose and meaning. According to the Egyptian Director of Antiquities, Zahi Hawass, the boats to the south of the pyramid are solar boats in which the soul of the king symbolically travelled through the heavens with the Sun god. Others suggest that the pit, which lies parallel to the causeway, might have contained the funerary boat used to bring the king’s body to its final resting place. But that raises the question as to why the boat was not returned to other duties after completing this task, instead of being so carefully interred at Giza. It seems to us that the boats were placed in their pits for a supposed future purpose rather than because they were no longer needed.

To us, it seems that Dr Hawass is probably quite close to the mark. As Egyptian religious beliefs developed, Pharaohs were buried along with artefacts necessary for use in the afterlife, and therefore is seems reasonable to assume that these boats were packed away so expertly for later use – for the dead king’s journey to the Duat, the realm of the dead that existed amongst the stars.

Slightly later records from the pyramids of Saqqara tell us the way that ancient Egyptian kings thought about the journey to the afterlife – which was all about sailing to the stars. There is no doubt whatsoever that Orion’s Belt and Sirius were of special importance to the ancient Egyptians. Amongst the inscriptions found on the walls of the Saqqara pyramids is the following incantation:

Be firm, Oh king, on the underside of the sky with the

Beautiful Star upon the Bend of the Winding Waterway…

The Beautiful Star of Isis is Sirius (Sopdet to the ancient Egyptians), which, at its heliacal rising at the summer solstice, marked the opening of the life-bringing Nile flood. This was the flooding that brought life back to the entire land of Egypt. It is, of course, to Sirius that the three stars of Orion’s Belt point.

A few weeks after the annual inundation began, the swollen Nile would be lapping against the edge of the Giza Plateau. Anyone standing next to Khufu’s pyramid looking southwards, towards Sirius rising before dawn at this time of year, would see the light of the billion stars of the Milky Way reflecting on its surface so that the horizon itself melded into a continuous waterway, right from their feet and extending far up into the heavens. Could it be that the kings believed that their boats would set sail at the moment that Sirius broke above the waterway, leading the way for their voyage to the Duat? The Saqqara inscriptions seem to describe it, and the boats were ready for the journey.

The Egyptians associated their gods with constellations, or specific astronomical bodies. The constellation Orion was considered to be a manifestation of Osiris, the god of death, rebirth, and the afterlife. The Milky Way represented the sky goddess Nut who gave birth to the Sun god Ra. The horizon had great significance to the Egyptians, since it was here that the Sun would both appear and disappear on its daily journey. The Sun itself was associated with a number of deities, depending on its position within the sky. The rising Sun was associated with Horus, the divine child of Osiris and Isis. The noon Sun was Ra, god on high, and the evening Sun was Atum, the creator god who lifted Pharaohs from their tombs to the stars.

The red glow of the setting Sun was considered to be the blood of the Sun god as he ‘died’ and became associated with Osiris, god of death and rebirth. This led to the night being associated with death, and the dawn with rebirth and life.

It seems to us that great kings such as Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, who saw themselves as gods in life, expected to take up their new life, after earthly death, by travelling to the stars – the realm of the gods. But how did they expect to get there? According to the records left to us, the answer is by sailing down the Nile and past the horizon into the heavens and onwards to Orion.

And in what did they expect to sail? Surely the boats, so carefully packed away next to the pyramids, provide a large and tangible clue? And the next question then has to be: How exactly did they envisage this journey happening?

As far as we are aware, there is no known Egyptian text that explicitly describes the anticipated structure of the world of the afterlife – the heaven amongst the stars. But the later Greek culture drew heavily on Egyptian ideas and they described the starry heavens as follows:

The heaven is solid and made of air (mist) congealed by fire, like crystal, and encloses the fiery and air-like (contents) of the two hemispheres respectively.

Aetius, II, 11, 2

The fixed stars are attached to the crystal sphere; the planets are free.

Aetius, II, 13, 2

So, the Greeks considered that the stars were attached to a crystal sphere that was fixed above and parallel to the surface of the Earth. It seems highly probable that the earlier Egyptians saw things in a similar way.

We put it to Robert Bauval that the ancient Egyptians may have built the pyramids as an earthly connection to the stars of Orion’s Belt. Not as a symbolic copy of the star arrangement in honour of Osiris, but a physical star-to-pyramid correlation – a direct conduit between the realm of men and the realm of the gods. The stages of the journey might have been something like this:

1. The three pyramids were carefully constructed to fit the stars – to effectively ‘plug into’ them. This was achieved by taking careful measurement of the star group, using a pendulum to time the gaps between the rising stars. After this, the timed swings of the pendulum were converted into pendulum lengths on the ground. The centre of each pyramid corresponded to the point of each star.

2. Each pyramid, and therefore star, was associated with one of the three kings (father, son and grandson). The largest pyramid, nearest the Nile is Khufu’s, the next Khafre’s and the smallest one, Menkaure’s.

3. The first star of Orion’s belt to rise above the horizon is Mintaka. Khufu was the first king to ‘rise’ at birth and to eventually ‘set’ at death. The second star is Alnilam and therefore corresponds to the next king, Khafre, and the third to rise is Alnitak, which makes it Menkaure’s star. (This has an obvious logic – but it does reverse the sequence as described by Robert Bauval.)

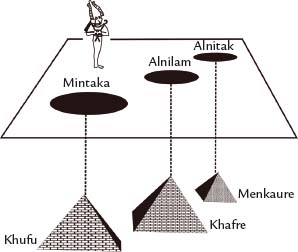

The evidence strongly suggests that the ancient Egyptian kings believed that the stars were on a plane parallel to the Earth and that they could stand in heaven and look down upon the land of mortal men. This explains why the pyramids were designed to correlate with the stars of Orion’s Belt as viewed from heaven rather than from the surface of the Earth.

Figure 15. The ‘crystal sphere’

4. The boats may well have brought the bodies of the deceased kings to the pyramids, but then they were dismantled and stored in the ‘graves’ prepared for them. The bodies of Khufu and Khafre were taken to their pyramids as they died 34 years apart. Then when Menkaure died 22 years later, the three kings were ready for their journey.

5. The ‘spiritual boats’, in other words the ‘essence’ of the boats that had been so carefully created and buried on the site, were assembled at the jetty in front of the pyramid complex in the same order as the pyramids. The dead kings set out to the stars with Khufu sailing south down the Nile in his mystical boat, followed by Khufu and then Menkaure.

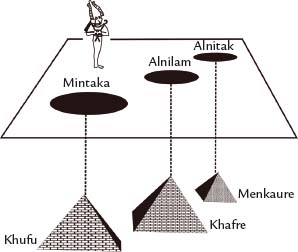

6. The journey began after dark and, as Sirius rose, the blaze of the Milky Way was perfectly reflected in the river to create a sparkling and uninterrupted waterway from Earth to heaven. Khufu’s boat, representing Mintaka, was first to cross the horizon. The three boats rose one after the other into the heavenly waterway and sailed in sequence up the Milky Way towards Orion’s Belt.

7. They sailed onto the plain of the stars that was parallel to the Earth but far above it; where even the mightiest of birds could not fly. Here the brilliant white stars existed on a celestial ‘ground’ – just like the equally brilliant white pyramids below them.

If this explanation were correct, it would mean that the relationship between the stars of Orion’s Belt is different to Robert’s original correlation. In this case the pyramids would be reversed and inverted in terms of the stars they represent. Instead of simply looking at Orion’s Belt from an Earth perspective, the key to the problem would be to look from the heavens downwards. From the parallel realm of the gods the deceased god-kings of Egypt could gaze down on the nation they once ruled.

We think that our revision of Robert’s Orion correlation theory has the benefit of fitting all of the available facts. Most particularly it largely removes the apparent inaccuracy in the layout of the pyramids in relation to the three stars – except for the anticipated tiny error in the deviation of the ‘dog-leg’. We explained our idea and Robert was not slow to respond.

‘This cannot be correct,’ he said, waving his hand from side to side. ‘You are proposing a level of accuracy in the position of the pyramids relative to each other that could not be achieved.’

We could not help but agree with his reasoning and yet the lateral error disappeared completely when our slight alteration of Robert’s evidence was introduced.

‘That is indeed strange,’ John Paul said with a nod and raised eyebrows. Perhaps he shared our view that it was an odd argument to suggest our explanation was wrong because it fitted the known facts ‘too’ well.

The boats of the kings were believed to sail to the afterlife in the order of the pyramids – Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure. They sailed down the Nile in order and at the horizon, where the Milky Way merged into its own reflection, the craft lifted off to sail up the ‘heavenly Nile’. They crossed the sky and arrived at Orion’s Belt so that Khufu became one with Mintaka (the first to rise), Khafre became Alnilam, and Menkaure was Alnitak.

Figure 16. Solar boats in the sky

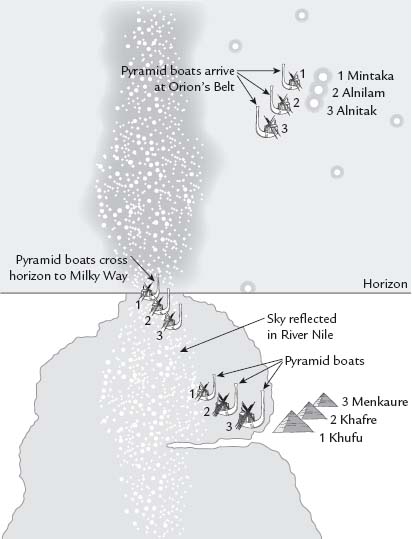

The back sight at Giza. The three pyramids are aligned at their southeastern corners. The line was aimed straight towards Heliopolis, the city of the sun, in the northeast. The point where each pyramid touches this virtual line marks the time gap between the stars of Orion’s Belt, measured in seconds- pendulum beats and converted to pendulum lengths on the ground. The greater gap is between Khufu’s Pyramid and Khafre’s Pyramid, demonstrating how the pyramid of Khufu represents Mintaka, not Alnitak as previously suggested by Robert Bauval.

Figure 17. Pyramids and back sight

One of Robert’s reasons for not wishing to pursue our suggestion was that he believed it had been aired before, for different reasons, in a very aggressive and public manner. In this case the attack had come from that icon of fair-mindedness and objectivity – the BBC.

The ability of the ‘establishment’ to rebuff new ideas, and particularly when that change comes from individuals deemed to be amateurs, should never be underestimated. It is right and proper that new ideas are put to the test but sometimes the process is less than objective. In 1999 the highly regarded BBC science programme, Horizon had set out to ‘rubbish’ Robert’s correlation theory. The two programmes were made with Robert’s cooperation, but he was unaware that they would be broadcast under the inflammatory titles ‘Atlantis Revisited’ and ‘Atlantis Reborn’. The Horizon team knew that anyone associated with the term ‘Atlantis’ is likely to be viewed as a fantasist.

Robert Bauval and Graham Hancock were both badly treated by these Horizon productions and, following a formal complaint, the Broadcasting Standards Commission judged that the central part of Horizon’s attack on Hancock and Bauval was indeed unfair. The complaint upheld by the BSC specifically identified Horizon’s unfair representation of the Giza-Orion correlation theory, in which Robert Bauval’s critic was given the opportunity to explain his point of view, but Robert’s own evidence was largely edited out.

For what it is worth, it is our opinion that Chris Hale, the producer of the Horizon programmes, was not knowingly dishonest – he was just a victim of his own prejudices. He explains his point of view in a section of a publication called Archaeological Fantasies, edited by Garrett G Fagan.1 Hale has some fundamental issues with an aspect of claims made by Hancock and supported by Bauval, and this led him to give a very partial review of the evidence regarding the Orion correlation theory. We discuss this collision of thinking styles in Appendix 10, which we believe has considerable implications for the broader process of identifying what constitutes legitimate approaches to reasoning.

It is human nature to protect ideas that we have adopted over many years of reasoning and very few people are willing or able to deal with new information that is not a small or incremental adjustment to embedded ideas. It matters not whether someone is a world-class professor in his or her subject or a believer in alien abductions – people seek out information that supports existing assumptions and reject anything that would demand a major overhaul of their existing world-view. This not only applies to ideas themselves but to the method of reasoning used.

And Robert Bauval is no exception, but in this case for the good reason that he believes he has dealt with the point we were making when he countered the Horizon attack. We fully understand that our suggested variation on the correlation theory looked similar to the one raised by Ed Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. Interviewed for the Horizon programme the American astronomer had said:

When The Orion Mystery came out my curiosity was naturally aroused. Anybody coming up with a good idea about ancient astronomy I want to know about it. And in going through the book there was something nagging me. In The Orion Mystery there’s a nice double-page spread (showing two pictures of the Giza Pyramids and Orion’s Belt) and anybody looking at this would say, ah! Giza pyramids, Belt of Orion, one kind of looks like the other, you know, you’ve got three in row, three in a row; slanted, slanted; we’ve got a map!

Immediately, Krupp had painted the picture of a halfwit seeing two sets of three objects in a bent row and leaping at the unwarranted assumption that there was a direct connection. This failure to mention a whole raft of reasons for the proposed connections feeds the preconceptions of the conventionalist group. Krupp continued:

And what I was bothered by turned out to be really pretty obvious. In the back of my head I knew there was something wrong with these pictures, and what was wrong with these pictures in their presentation is that north for the constellation of Orion is here on the top of the page. North for the Giza pyramids is down here. Now they’re not marked, but I knew which way north was at Giza and I knew which way north was in Orion. To make the map of the pyramids on the ground match the stars of Orion in the sky you have to turn Egypt upside down, and if you don’t want to do that then you have to turn the sky upside down!

Krupp’s argument was not exactly insightful. Apart from a completely arbitrary modern convention, why assume that north equals the top and south the bottom? Some people are still confused by the fact that Upper Egypt is in the south of the country and Lower Egypt is the northern half. This description refers to the fall of the River Nile from the higher altitudes towards sea level at the delta that spews the Nile’s fresh water into the Mediterranean.

What we were trying to say to Robert was quite coincidentally related to Krupp’s comment but arrived at for entirely different reasons. In fact we believe our description of events negates Krupp’s objection and makes the correlation theory sounder than ever.

In the Introduction to the aforementioned book, Archaeological Fantasies, the editor says:

Whatever is theorized about the pyramids must be coherent with the way in which other aspects of Egyptian civilization are described.

This is obviously good advice – most of the time. But it would be foolhardy to insist that it is a rule that must always be applied in all cases as stated here.

It is important to keep an eye out for the completely unexpected. One eminent geologist from Cambridge University once said to Chris: ‘You are assuming a closed system. What if it was not a closed system?’ He had been responding to Chris’s comment that the ancient global flood stories, such as Noah’s Flood, cannot be true because there is not enough water to flood everywhere simultaneously. In this case, what if the Egyptian pyramid builders were directly influenced by a group from outside their own culture? If we automatically rule out candidate ideas to explain the available evidence, just because they don’t seem to fit our previous expectations of the culture, it would be impossible ever to spot the arrival of a major external influence.

One of the criticisms of Robert Bauval’s theories regarding the Giza pyramids is the apparent over-emphasis of stellar issues involved, when the Old Kingdom is generally considered to have been overwhelmingly a solar orientated culture. The importance of the Sun to these people is beyond question, from the god Ra to the incredibly important city of Heliopolis. It was only much later, most probably as a result of Babylonian influences, that Egyptians are known to have taken a serious interest in astronomy.

Before the primary pyramid age, and indeed for some considerable time after it, the study of stars does not appear to have been of specific importance to the ancient Egyptians. Yet the pyramids do seem to imply a great interest in the stars and this is also borne out by many of the ‘spells’ or ‘incantations’ included amongst the Pyramid Texts. And if we are right about the pendulum method used to map the stars onto the Giza Plateau, the level of observational astronomy amongst whoever planned the pyramid sites must have been considerable.

So where did this astronomical knowledge come from?

Before we deal with this question, it is worth looking at one anomaly regarding the pyramids. This anomaly concerns the ruined pyramid of Djedefre, which stands about eight miles north of Giza at a place now called Abu Rawash.

Djedefre was the successor and son of Khufu and he became king in 2528 BC, upon the death of his father. He apparently died eight years later when his brother Khafre came to the throne, who was in turn followed by his son, Menkaure. The question is, if the three pyramids of Egypt were, as is normally accepted, conceived as a single project, why was Khufu’s eldest son excluded from the plan by having his pyramid constructed inland of the Nile and further north?

The name Djedefre means ‘enduring like Ra’ and he was the first king to use the title Son of Ra as part of his royal title, which is generally considered to show an indication of the growing popularity of the cult of the solar god Ra. Could it be that this king had no time for newfangled, and perhaps alien ideas about stars being as important as the Sun?

A boat pit has been found at this pyramid, but it was empty apart from fragments of over 100 statues, mostly representing Djedefre on his throne. Three more or less complete heads were found, including one now in the Louvre in Paris and another that resides in the Egyptian Antiquity Museum in Cairo. The statues appear to have been deliberately destroyed, as though to deny the king’s status. It is widely thought that there were deep rifts and that Djedefre had gained the throne by murdering his older half-brother, Kauab. He then married his sister Hetepheres II, widow of his dead half-brother, to strengthen his claim to the throne, as his own Libyan mother was a ‘lesser wife’ with no ties to the royal family.

Perhaps because of the break with his father’s family, Djedefre moved his mortuary temple and monument north to Abu Rawash, where he began to construct a large pyramid. This structure had only risen to about 20 courses when he died. The possibility of a family feud looks all the more likely because work on the pyramid was stopped immediately. Furthermore, there are no explanations as to why Kauab was not succeeded by any of his own sons, Setka, Baka or Hernet, so it may have been that they all died before, or at the same time as, their father.

It has been further widely speculated that Khafre murdered Djedefre, and then destroyed all images associated with his brief rule of just eight years. And it is possible that he also killed Djedefre’s sons to remove any competition for the throne.

It is certain that all Egyptian kings had respect for Ra and we already knew that the back sight, which links the three Giza pyramids, points northeast towards Heliopolis, the city of the Sun. But Djedefre shows an even greater liking for Ra. From his pyramid at Abu Rawash, the summer solstice Sun rises out of Heliopolis – a fact that must surely have driven the king’s choice of location.

Was Djedefre cut out of the plan completely? The available evidence now suggests not.

The feud theory is now under question, as the broken statues seem to have been smashed during the Roman and Christian era. Furthermore, it would also appear from fragmentary evidence around his pyramid that, after Djedefre’s death, he enjoyed a lengthy cult following that was not disrupted by his successor. Why Djedefre chose to build his pyramid at Abu Rawash is still considered a mystery, but there is evidence that Djedefre definitely had a religious departure from his family. His pyramid has a number of elements that seem to revert to earlier times, while his adoption of a ‘son of Ra’ name indicates his religious deviations away from the stellar leanings of his father Khufu. Whether or not the sons of Khufu set about murdering each other in a fight for the kingship, there is good reason to believe that the family were all happily working together – at least during the lifetime of Khufu. Recent evidence suggests that it was Djedefre who completed his father’s burial at Giza and was responsible for the provision of his funerary boats, where Djedefre’s name has been found.

And we believe that there is a perfectly good explanation as to why Djedefre’s pyramid is at Abu Rawash and not Giza.

No one appears to have looked closely at the relative positions of the pyramids associated with Khufu and his sons Khafre and Djedefre. Using satellite mapping we measured the distance between Djedefre’s pyramid and Khufu’s at Giza. The first thing that leaped out was the angle of the straight line. Drawing a line from the northwest corner of Djedefre’s pyramid, through its centre and the southeast corner and onwards for just over 8 km, it intersects Khufu’s pyramid at the northwest corner, continues through its centre and then hits the southeast corner. The pyramids are as perfectly aligned as Khufu’s is with Khafre’s.

Khufu’s pyramid is aligned so that the diagonals of its sides are both perfectly aligned to the pyramids of his two sons. It looked for all the world as though Khufu was facing the setting Sun and stretching his arms out toward his sons exactly 90 degrees apart. The chances of this arrangement happening by accident are virtually nonexistent, and it must have taken great skill to get the alignment so accurate over a distance well beyond the horizon. So we conclude that even this distant pyramid was part of a complex plan created by Khufu during his lifetime. It may be that he accepted Djedefre’s single-minded religious beliefs concerning Ra, the Sun, but still wanted to involve him the largely star-orientated theology that he had been developing, to ensure that he and his progeny found an eternal home in the Duat above.

When we looked at the distance between Khufu’s and Djedefre’s pyramids it was 8,218 m centre to centre, which was immediately interesting. We then measured the distances between the locations of each sarcophagus and found that the mummified bodies of the two kings had been placed 8,235 m apart – which, to an accuracy of 99.6 per cent, happens to be 10,000 Megalithic Yards!

So, let us now return to question as to where the astronomical knowledge underpinning the planning of the pyramids came from. Our answer is that it came from the British Isles – and there are very hard-edged reasons for making this apparently outlandish claim.

The British Isles, along with some other parts of Western Europe, still has the remains of tens of thousands of structures used for tracking and measuring the movements of the Moon, planets and stars. Thornborough itself had been in use for almost a millennium before the pyramids were built. Given that both the henges of Thornborough and the three pyramids of the Giza Plateau appear to be built in the form of Orion’s Belt, there are three possible explanations for the connection.

First, it could be that there is no connection at all. It is simply that two different cultures naturally focused their attention on Sirius, the brightest of all stars, and then noticed a nearly straight line of three stars rise ahead of it and point almost at it. They then attached some mystical significance to these stars and decided for some reason to build a model of them on the ground.

The second option is that there was contact between the ancient Egyptians and the people of megalithic Britain, and the Egyptians adopted the beliefs of the Northerners by merging their star-based astronomical ‘magic’ into their existing solar theology.

The third possibility is that the astronomical priesthood of the British megalithic culture was actively involved in the design and layout of the pyramids. Whilst all of the evidence shows that the people of Britain were far behind the Egyptians in terms of stone building and the production of bronze tools, they were clearly ahead in their astronomy and the adoption of complex multifunctional measuring systems. Critics might argue that any association between these two groups would have led to the adoption of metals in Britain at a far earlier date, but we have good reason to believe that this would have been an anathema to the megalithic priesthood. This is an argument too complicated to enter into within the scope of this book. To follow this third, ‘strong’ version of the British-Egyptian theory, it could be that either the megalithic priests came to Egypt or that the Egyptian kings sent their builder-priests north to investigate the ‘magic’ of the stars understood by a people they had learned about.

The evidence suggests it was the latter of these options that occurred.

If the pyramids were placed as we have argued – by timing the stars of Orion’s belt rising and then converting the pendulum lengths used into linear units – then we can detect where and when it was done. This is because the angle of the rising of the stars changes by latitude, and when we looked at the rising of the stars of Orion’s Belt at Giza in circa 2500 BC we found no correlation whatsoever with the actual layout of the pyramids in any units at all.

But then we tried Thornborough and the fit was immediate – and astonishingly accurate! Using standard astronomy software we took the timings on the autumn equinox at Thornborough on 14 October in 2500 BC and we found that the three stars rose at following times of day, using a 24-hour clock:

Mintaka 21:02:27

Alnilam 21:10:49

Alnitak 21:18:11

As we have previously said, it is the two outer stars that have to be measured at rising because the dogleg of the middle star distorts the true timing and therefore ultimately the linear distance between the stars. This means that the time taken between the rising of Mintaka and Alnitak was 15 minutes and 44 seconds – a total of 944 seconds.

The time lag between the rising of the first and last stars represented 944 swings of a seconds-pendulum that was 99.55 cm in length: 944 such lengths would measure 940 m. The gap between the centres of Khufu’s and Menkaure’s pyramid, as best as we can tell, is 942 m. This gives a fit of 99.8 per cent, which is as close to perfect as it is possible to get, given that we could be slightly out in our estimations of the true distance between pyramid centres, and bearing in mind that the Egyptians could have been slightly out in placing them.

Either it is a huge coincidence that both structures are copies of Orion’s Belt and the measure of the stars at Thornborough in 2500 BC fit the pyramids’ position on the ground, or there is a connection. It becomes obvious that further and quite extensive research into possible connections between the two cultures in question is going to be necessary. From our own point of view we remain utterly convinced that the three major pyramids on the Giza Plateau were built upon a footprint that was not created first on the desert sand by the side of the Nile, but in the green and pleasant land of North Yorkshire. Both the Thornborough henges and the Giza Pyramids were planned by engineers, and engineers cannot avoid leaving evidence of their presence. In both these cases we can see their footsteps as clearly as if they walked this way yesterday.