). This comes from the root Halal (

). This comes from the root Halal ( ), which is normally translated as “to praise.” The Psalms are therefore most often simply viewed as nothing more than a series of praises to God.

), which is normally translated as “to praise.” The Psalms are therefore most often simply viewed as nothing more than a series of praises to God.Looking at these terms relating to meditation and contemplation, it immediately becomes obvious that many are found in the Psalms, often in a sense where they most strongly suggest higher states of consciousness. This is particularly true of the 119th Psalm, from which we have already quoted a number of passages highly suggestive of meditative states. This would suggest that in Biblical times the Psalms played an important role in the meditative disciplines.

It would therefore be of some interest to make an etymological analysis of the Hebrew name for the Psalms, which is Tehillim ( ). This comes from the root Halal (

). This comes from the root Halal ( ), which is normally translated as “to praise.” The Psalms are therefore most often simply viewed as nothing more than a series of praises to God.

), which is normally translated as “to praise.” The Psalms are therefore most often simply viewed as nothing more than a series of praises to God.

The root Halal, however, has two other meanings which are very significant from our viewpoint. The first is that of brightness and shining, as in the verses, “Behold the moon does not shine (halal)” (Job 25:5), and, “When [God's] lamp shined (halal) over my head” (Job 29:3). The second connotation is that of madness, as in the noun Holelut ( ), referring to the demented state in many places in the Bible.69

), referring to the demented state in many places in the Bible.69

This would therefore indicate that the word Halal denotes a state where one leaves his normal state of consciousness, and at the same time, perceives spiritual Light. It is distinguished from the many other Hebrew terms for praise, since Halal is praise designated for attaining enlightenment through a state of oblivion.

The relationship between enlightenment and madness should not be too difficult to understand, since the Bible explicitly relates madness to prophecy. In one place, a prophet is called a madman, and the leading commentator, Rabbi Isaac Abarbanel, comments, “They called him mad, since as a result of his meditation (hitbodedut), he appeared demented, not paying attention to mundane affairs.”70

In another place we find an even more explicit parallelism. God says, “Every man who is mad, who prophesies, shall be put in the stocks” (Jeremiah 29:26). Here again, the commentaries, most notably Rabbi David Kimchi, state that many people considered the prophets to be mad because of their unusual actions. It was not unusual then, to use the term “prophet” as a synonym for madman.

The word Halal is thus related to the roots Lahah ( ) and Lo (

) and Lo ( ) which, as discussed above, denote states of negation. It is also related to the root Chalal (

) which, as discussed above, denote states of negation. It is also related to the root Chalal ( ), meaning hollow, especially in a spiritual sense. Such a level of “hollowness” is closely related to prophecy, this being the level of King David, who said of himself, “My heart is hollow (chalal) within me” (Psalms 109:22).

), meaning hollow, especially in a spiritual sense. Such a level of “hollowness” is closely related to prophecy, this being the level of King David, who said of himself, “My heart is hollow (chalal) within me” (Psalms 109:22).

All this indicates that Halal denotes negation of the senses and ego in the quest of enlightenment. The Psalms were therefore called Tehillim because they were especially designed to help one attain this exalted state.

This philological analysis might not be conclusive if it were not backed up by a solid tradition. In the Talmudic tradition there is a clear indication that the Psalms were used to attain the state of enlightenment called Ruach HaKodesh.

If one looks at many Psalms, one sees that they begin with either the phrase, “A Psalm of David” (Mizmor LeDavid) or “Of David, a Psalm” (LeDavid Mizmor). The Talmud states that when a Psalm begins with the phrase, “Of David, a Psalm,” this indicates that he recited the Psalm after he had attained Ruach HaKodesh. But when the Psalm begins with “A Psalm of David,” it means that David actually made use of the Psalm in order to attain his state of enlightenment.71 Thus at least eighteen of the Psalms were specifically composed as a means of attaining higher states of consciousness.

There is another intriguing statement regarding Psalms 90 to 100 in a Midrash. Psalm 90 is “A prayer of Moses,” and according to tradition, all eleven Psalms from 90 to 100 were also written by Moses. The Midrash notes that, “Moses said these eleven Psalms in the technique of prophecy.” 72 Although the interpretation is not conclusive, the Midrash may be teaching that these eleven Psalms were meant to be used as a means of attaining prophecy.

The Midrash goes on to say, “Why were these Psalms not written in the Torah [since they were written by Moses]? Because one deals with Law, and the other with Prophecy.” The Torah must deal primarily with Law, while things dealing with prophecy and mysticism have their proper place in the Book of Psalms.

Upon close examination, we find that there is some additional evidence to support this. The Talmud states that Psalm 91, one of these eleven, is called the “Psalm of the Stricken Ones.”73 The Midrash states that when Moses ascended into the spiritual realm on Mount Sinai, he recited this Psalm in order to be protected from the forces of Evil.74 Hai Gaon (939–1038), one of the important early masters of the mystical arts, writes that these “stricken ones” include such as Ben Zomah, who was stricken with insanity when he attempted to penetrate the mysteries of the Merkava. This Psalm was meant to protect the ascending mystic against such mishap.75

Another Psalm, which, according to the Zohar, was used especially to evoke the prophetic spirit, is the seventh Psalm.76 This Psalm is called a Shiggayon, and according to at least one Midrash, this name is related specifically with the quest of the spirit of enlightenment and prophecy.77 This would also explain the meaning of the mysterious word Shiggayon ( ). which causes the commentaries much trouble. According to this interpretation, its base would be the single letter Gimel (

). which causes the commentaries much trouble. According to this interpretation, its base would be the single letter Gimel ( ), and it would thus be related to Nagan (

), and it would thus be related to Nagan ( ), “to play music,” and Hagah (

), “to play music,” and Hagah ( ), discussed earlier. It would thus be a Psalm used specifically for Hagah-meditation.

), discussed earlier. It would thus be a Psalm used specifically for Hagah-meditation.

The fact that the context of this Psalm deals with the singer's enemies rather than higher spiritual concepts does not contradict this. These enemies actually refer to the Klipot and forces of Evil which form a barrier, endangering one who would climb the spiritual heights. The first step in ascending to the higher spiritual levels therefore involves passing through the domain evil, this being indicated by the “stormy wind, deep cloud and flaming fire” in Ezekiel's vision. The primary purpose of the Shiggayon, like Hagah-meditation, is to clear the mind of the mundane and overcome these “enemies.” A major mystic and Kabbalist, Rabbi Joseph Gikatalia (1248–1305), explicitly writes that this was the purpose of all the Psalms.78

Of all the Psalms, however, the most interesting is the 119th Psalm. Even in structure, this Psalm is different than any other passage in the Bible. It is in the form of an alphabetical poem or chant, with eight verses for each letter of the Hebrew alphabet. There is one other thing that also strongly draws our attention to this Psalm. This is the fact that all the words which we have determined to refer to meditation and meditative states occur in this Psalm in a disproportionately high number.

One significant feature of this Psalm is the fact that each letter is repeated eight times. This becomes very important when one realizes the meaning of the number eight. Although this is discussed in a number of places, the clearest analysis has been made by the eminent Kabbalist and mystic, Rabbi Judah Low (1525–1609), the “Maharal” of Prague, famed as the maker of the Golem.

According to the Maharal, the number seven refers to the seven days of creation, and hence, this number always denotes the perfection of the physical world. The number eight is the next step, and therefore eight denotes one step above the physical. Whenever we find the number eight used, it is in reference to something that brings one into the spiritual realm.79 Elsewhere, the Maharal states that this is precisely the significance of the eightfold repetition in the 119th Psalm.80

The Maharal speaks of the number eight with regard to circumcision, which is always performed when the child is eight days old. Sex involves some of man's deepest emotions and strongest desires. In giving Abraham a covenant related to the sex organ, prescribing it for the eighth day, God indicated that these emotions and desires would henceforth be used for the mystical quest of the Divine on a transcendental level.

Very closely related to this concept is the fact that the High Priest (Cohen Gadol) would wear eight garments while serving in the Temple.

It is significant to note that before giving Abraham the commandment of circumcision, God told him, “Walk before Me and be complete (tamim)” (Genesis 17:1). This is also the key word in the first verse of this 119th Psalm: “Happy are those who are complete (tamim) on the way” (Psalms 119:1).

The word Tamim( ) denotes spiritual completeness, where one can attain the eighth level, above the mundane. Thus, after forbidding various occult practices favored by the pagan Canaanites, God said, “You shall be complete (tamim) with the Lord your God” (Deuteronomy 18:13). As the renowned exegete, Rabbi Isaac Abarbanel, explains, the word Tamim has the connotation of true enlightenment and prophecy, as distinguished from spurious mystical states.81

) denotes spiritual completeness, where one can attain the eighth level, above the mundane. Thus, after forbidding various occult practices favored by the pagan Canaanites, God said, “You shall be complete (tamim) with the Lord your God” (Deuteronomy 18:13). As the renowned exegete, Rabbi Isaac Abarbanel, explains, the word Tamim has the connotation of true enlightenment and prophecy, as distinguished from spurious mystical states.81

According to some Kabbalists, the word Tamim is closely related to the word Teomim ( ), meaning “twins.”82 When a person is complete—Tamim— then he is like a “twin” to the Supernal Man—the “Man” that Ezekiel saw sitting on the Throne. An individual who reaches such a level is then worthy of communing with the supernal Forces.

), meaning “twins.”82 When a person is complete—Tamim— then he is like a “twin” to the Supernal Man—the “Man” that Ezekiel saw sitting on the Throne. An individual who reaches such a level is then worthy of communing with the supernal Forces.

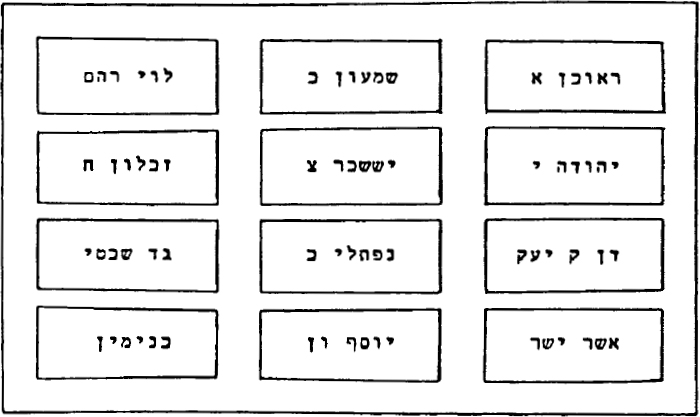

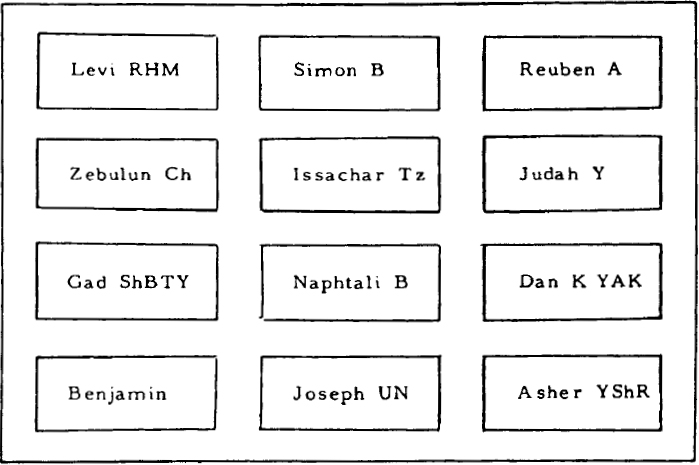

This also explains the meaning of the Urim and Thumim. These consisted of twelve stones, set into the High Priest's Breastplate (Choshen), and inscribed with the names of the tribes of Israel.83 This Breastplate was one of the Eight Vestments worn by the High Priest in the Temple.

According to some, the Urim and Thumim also consisted of a parchment containing the 72 letter Name, which was placed in the Breastplate.84 According to the Kabbalists, the names of the tribes and other words inscribed on the twelve stones also contained exactly 72 letters.85 This is significant, since, as we have discussed, the 72 letter Name plays an important role in the attainment of the prophetic state.

We have already discussed how the word for the Breastplate, Choshen, has the connotation of a mystical experience and revelation. It is also significant to note that the Urim and Thumim could only be used by the High Priest when he was wearing all Eight Vestments.86 In using the Urim and Thumim, the Priest would reach the eighth level, transcending mere physical perfection and entering the spiritual domain.

According to the Talmud, the Urim and Thumim were actually used as the subject of mystical contemplation. The High Priest would contemplate the stones of the Urim and Thumim, meditating until he reached the enlightened state of Ruach HaKodesh. He would then see the letters on the stones light up, spelling out the necessary message.87

This explains the meaning of the terms Urim and Thumim. The word Urim ( ), clearly comes from the word Or (

), clearly comes from the word Or ( ) meaning “light.” This indicates that the letters actually light up.88 The word Thumim (

) meaning “light.” This indicates that the letters actually light up.88 The word Thumim ( ) is derived from the word Tamim, under discussion.89 This indicates that the Thumim would bring the High Priest to the level of Tamim, the completeness and perfection implied by Ruach HaKodesh.

) is derived from the word Tamim, under discussion.89 This indicates that the Thumim would bring the High Priest to the level of Tamim, the completeness and perfection implied by Ruach HaKodesh.

Thus, when the 119th Psalm speaks of those “Complete on the way” (Tamim Derekh), it is speaking of those who are seeking enlightenment and the transcendental experience. One gets a definite impression that it was actually a Psalm changed by people seeking enlightenment, perhaps even the disciples of the prophets in their quest of the prophetic experience. As such, it could have been a like a long mantra, chanted in a prescribed order until it brought the individual to a high meditative state.

In this context, it is significant to note that the Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760), founder of the Hasidic movement, made use of this Psalm. He was taught by his spiritual Master that if he said the 119th Psalm every day, he would be able to speak to people, while at the same time maintaining a transcendental state of attachment to the Divine.90 Thus, even among the later mystics we find that this Psalm played an important role.

Once we understand the meaning of the terms relating to meditation and the meditative state, we can accurately translate this Psalm. It immediately becomes evident that many passages are highly suggestive of the mystical experience. The Psalm speaks of the person walking the path of enlightenment, seeking higher states of consciousness, while at the same time asking to be delivered from error and other dangers facing those who ascend this spiritual heights.

In Your mysteries I meditate (siyach)

And I gaze at Your paths;

In Your decrees I am enraptured (shasha)

I forget not Your word;

Ripen Your servant

I will live and watch Your word;

Uncover my eyes, I will behold

Wonders from Your Torah.91

. . . .

Let me understand the way of Your mysteries,

I will meditate (siyach) in Your wonders;/

my soul melts from meditation (tugah)

Support me as Your Word;

Remove me from a false way,

Favor me with Your Torah;

I have chosen a way of faith,

Your judgments make me stoic;

I have bound myself to Your testimonies,

O God, let me not be deceived;

I run the way of Your commandments,

For You have expanded my heart.92