MIDSUMMEr

midsummer

The wildflower blossoms of May fade in the hay-scented breezes of June and ferns unfurl, giving the shaded woodland garden the lush, green appearance of a tropical rain forest. Along the stone wall, at the back of the vegetable garden, tall spikes of iris stand above clusters of sword-blade leaves. They burst into blossom of every conceivable combination of purple and yellow pigment—and a few too strange to be believed, as exotic as jungle orchids, with names like “Rocket” and “Millionaire,” “O Suzanna” and “Ecru Lace.” They stand proudly in the noonday sun, while secretly, in the crevices of the stone wall behind them, spiders lie in ambush or spin silken traps and wait to pounce menacingly on a careless moth or preoccupied gardener.

As the month progresses, the afternoon hours become uncomfortably hot, but evenings are still spent outdoors, on the back porch where fireflies twinkle in the grass and warm animal smells drift down from the sheep pen and chicken coop.

At Midsummer it is traditional to make amulets of protection out of various herbs for homes and animals. Boughs of rowan were hung up over the entrances to stables and cow barns, sheep and goat pens, and chicken coops as protection against any evil magick which might cause harm or disease to the livestock. Today not everyone keeps horses, sheep, or cattle, but anyone who has a pet a dog, cat, parrot, or toad may wish to hang a sprig of rowan over their “place” to give the special protection of magick to a beloved pet or companion.

Rue is also an herb of protection. As rowan protects against evil magick, rue protects against poison and disease; although rue itself, if ingested in excess, can be a poison. It is native to the Mediterranean countries of Europe, and was such an important medical herb in Italy that replicas of it were made in silver to be worn as amulets against the Evil Eye. Italian Witches also sewed sprigs of rue into a small pouch along with bits of bread, a pinch of salt, and a couple of anise seeds, using a red thread and saying words like:

Herb of rue, let this charm

Protect my family from harm.

In England, rue was believed to be protection against the spells of faeries; and witches in France included it in their flying ointments, but it had to be accompanied by these words:

By yarrow and rue

And my red cap too,

Hie over to England!

Rue is an herb that grows nicely in this country, although it dies in winter. Its medicinal properties, those of an emmenagogue, which stimulates the action of the smooth involuntary muscles, are lost when the herb is dried (but might be preserved by freezing). Its magickal properties for protecting against poison and disease, evil magick, and the mischief of faery-folk, however, are longer lasting, and for this purpose it is traditionally gathered at Midsummer.

An herb that is practically synonymous with Midsummer is St. John’s wort. In fact, its name came from St. John’s Day, the name given to the Summer Solstice by the Church in an attempt to abolish Pagan celebrations. St. John’s wort is ruled by the sun. Its flowers are the bright yellow that symbolizes the sun, and the arrangement of its foliage show the four spikes of the Sun Wheel. The plant, too, yields a sunny yellow dye. St. John’s wort has the power to bind spirits, and it is traditionally gathered at Midsummer and hung for this protection.

An ancient chaldean magickal text gives this charm for protection:

Fleabane on the lintel of the door I’ve hung,

St. John’s wort, caper, and wheat ears.

Here at Flying Witch Farm, we make little amulets out of a sprig of rowan, a sprig of rue, and some St. John’s wort. If the St. John’s wort isn’t ready yet, and it isn’t this far up the Delaware, then we use a pinch of the herb gathered last year and put it in a little red pouch. This we tie together with the sprigs of rowan and rue using red yarn. We hang one amulet in the sheep’s stall and one in the chicken coop, one over the dog’s bed, and one over the front door with these words:

Herbs of the sun, work your charm

Protect these animals (or this house) from harm.

As we hang up the new amulets, we take down the old ones which are very dry and burn nicely on the Midsummer fire.

Woodbine (woody nightshade or bittersweet) is also hung over stable doors for protection, and Scottish witches would pass a patient through a wreath of it nine times as part of a healing charm.

There are a number of herbs which are traditionally gathered at Midsummer. Vervain is an herb closely associated with the Summer Solstice, and as magickally powerful as St. John’s wort. Its magick is the magick of purification, and it has the power to banish evil or negativity. It is traditionally gathered Midsummer morning with the left hand.

The Greater Key of Solomon contains instructions for making an “aspergillum,” or magickal sprinkler, using a sprig of vervain and eight other herbs, including sage, mint, basil, and fennel. But in Pagan times, vervain was usually used alone to dispel negativity and invite joy into the home. The Key of Solomon requires that the herbs be bound with yarn spun by a maiden, but the Pagan knows that the Mother is as pure as the maid, and does not acknowledge the symbolism of the new religion. The aspergillum of the ceremonial magician has a wooden handle inscribed with signs and symbols, but a simple Pagan water sprinkler can be made with vervain alone, or with vervain, rosemary, and hyssop, which also have magickal purifying properties. Tie the bunch of herbs together with pure white yarn, spirally binding the stems together to form something of a handle.

This can be used to cleanse and purify objects such as jewelry purchased at an antique shop, or a second-hand crystal ball. It can also be used to banish the negative feeling that seems to linger in your home after it has been visited by people with very unhappy attitudes.

To use this tool, dip it in a bowl of spring water and sprinkle the article; or walk through the rooms of your home with the bowl of water and a bundle of herbs, sprinkling as you go, and saying words like:

By rosemary, hyssop and vervain

Evil spirits, be gain, be gain!

This is not to be confused with the consecration of the magick circle by the element of water, which is performed only with a bowl of water and the fingertips. The purpose of this ritual is to charge the circle with the magick of the element of water, not to purify it with the magick of any herbs.

Finally, it is sometimes instructed that after gathering vervain, an offering of honey should be made to the earth; but in fact, honey attracts ants which could eventually harm the vervain. An offering of water or plant food would be far more appropriate.

Mistletoe, sacred to the Druids (as was vervain), was also ritually gathered at Midsummer. At this time of year, it is without berries and is valued as an amulet of protection (at Yule it is with berries and is an amulet of fertility). Mistletoe was the only creature that could kill Balder, the Sun God of Germanic and Nordic peoples. It is suggested in ancient texts that it has power over life and death. On the day of Midsummer, at high noon, when the God of the Sun is at the peak of his power, the sacred mistletoe was cut in the oak groves of the Druids. As everyone knows, this was done with a golden sickle, and the precious herb fell onto white linen so that its magickal power would not be grounded.

Today many Pagans and Wiccans use a white-handled knife to cut sacred and magickal herbs, but the origin of this knife is in ceremonial magick and not in Paganism. As we are in the process of stripping away the masks and disguises of the new religion to reveal the true Pagan face of our own traditions, so we should be removing the concepts and paraphernalia of ceremonial magick, or at least recognizing them for what they are.

A truly Pagan device for the gathering of herbs would be a tiny sickle of brass (bronze), formed in the shape of a crescent moon. The blade could be made easily enough by cutting the crescent blade out of heavy gauge sheet brass available at many hobby shops. The blade need only be about three inches long. The cutting side can then be beveled with files, and finally brought to a sharp cutting edge with a whetstone or an old fashioned knife sharpener. Once the cutting edge has been established, the blade can be inscribed with runes or symbols, and a wood handle might be added for comfort.

Another would be a blade of flint or obsidian, or of stag antler. This, as well as the blade of bronze, would need to be kept in a leather sheath when not in use to protect its fine, sharp cutting edge. A quick cut with a sharp edge is the most humane way to sever the leaves or sprigs, as it also allows the plant to heal quickly and without infection. In some vineyards, where a great deal of pruning is done, pruning shears are periodically washed in isopropyl alcohol to prevent the spread of bacterial infection.

One final reason for the use of bronze or flint over the white handled knife is the fact that the early instructions for gathering herbs specifically forbids touching certain kinds of plants with iron or steel. Though these instructions are obviously the product of the Iron Age, such instructions have an air of antiquity about them, and seem to suggest a tradition that predates the Iron Age.

Another herb that is traditionally gathered at Midsummer is lavender, whose tiny purple spikes of aromatic blossoms now rise above the dusty gray foliage. Ruled by Mercury, the flowers of lavender are the basis of many an herbal incense blend and bath mixture. The plant was not native to Egypt, but was grown in the temple gardens there and it was burned as an offering by the ancient Greeks. Dried blossoms are still today used to make traditional incense for Midsummer rituals.

It was also traditional to gather the fern seed on Midsummer’s Eve for the purpose of making one’s self invisible. Ferns, however, are nonflowering plants, and as such, do not have seeds. They do have spores, though, which in a sense are seeds. These are so tiny as to be invisible.

They are contained in tiny organs which are arranged in neat rows on the underside of leaves of certain species of ferns. Gathered on Midsummer’s Eve and worn in one’s shoe (still attached to the fern leaf), they will aid a person to go about unnoticed if they wish to. Also, the root of the male fern with the embryonic leaves still attached, dried over the Midsummer fire, is the “lucky hand” amulet.

An old Anglo-Saxon herbal gives a lengthy poem called the “Nine Herb’s Charm.” It tells of the virtues of nine of the herbs believed to be the most powerful medicinal herbs of that time. Today the identity of some of the herbs are in doubt. Nevertheless, the first of the nine herbs that the poem praises is mugwort. This is one of the herbs most highly valued by modern witches for its magickal powers. An infusion of the herb is used to bathe crystal balls, scrying mirrors, and some amulets on the night of the full moon in order to recharge or enhance their ability to give psychic visions. Little pouches containing mugwort and bay leaves help to induce prophetic dreams. It was also believed in times past that to wear a leaf of mugwort in one’s shoe on a journey (or under the saddle, if going by horseback) would make the trip less tiring.

The second herb of the charm is plantain. A common weed today, it was once considered one of the very few herbs that could mend broken bones. It was brought to this country by some of the very first white settlers, and it spread so rapidly that the Native Americans called it “White Man’s Footprints”; however, many botanists believe that the plant was indigenous to North America.

Stime is the name given to the third herb of the charm, which has been interpreted as the moon-ruled watercress. While watercress was eaten by the Romans because it was believed to be a brain stimulant, the Greeks before them considered it a brain subduer.

The next herb in the charm is cock-spur grass, which is still used by some herbalists.

Mayweed is the fifth herb of the charm. It is a type of wild chamomile that prefers to grow in the poorest of soils, where almost nothing else will grow. It has some value in medicine, but it is more likely that the charm in the ancient herbal was referring to chamomile.

The mysterious name “wergulu” is given to the sixth herb of the charm. It has been interpreted as referring to the stinging nettle. If an herb can be defined as a useful plant, then stinging nettle belongs in every herb garden. No herb has had more uses than this one. The fibers of its stems have been spun and woven into fabric to make it more durable, some say even more durable than linen. It has also been made into rope and paper. It has been eaten as a green vegetable and as a soup green. Dried like hay, it has been fed to livestock and is said to increase egg production among hens and milk production among cows. The painful sting of the living plant, when planted as a hedge, however, forms a boundary that few domestic animals will cross. It is the food plant of some of our loveliest native butterflies, including the Red Admiral and the Painted Lady. And the seeds are a favorite food of several song birds. A tea brewed of the foliage is a tonic and a natural insecticide for seedlings in early Spring. It is also a healthful tonic for humans. The root yields a yellow dye for woolens, while the upper part of the plant produces a green dye. It has been used as a poultice to stop bleeding. The painful sting from the lightest touch of the nettle has caused it to be used in harmful magick, but the sting is lost when the herb is dried.

Apple is the seventh herb named in the ancient charm. Its fruit eaten once a day is said to keep the doctor away, and apples have been used to cure warts in remedies that are more magickal than medicinal. When cut in half horizontally the apple reveals a five-pointed star, and its wood and blossoms have been used in love charms.

The eighth and ninth herbs of the charm, thyme and fennel, are mentioned together. Both herbs have some value in aiding digestion, and both have the property of magickal protection. Thyme also is an ingredient in anointing oil prepared to enable one to see the faery kingdom.

Like Samhain, Midsummer’s Eve was a time for divining the future, especially for young girls who were interested in marriage. One method was to gather the buds of houseleek and name one bud for each eligible young man. The bud most opened on Midsummer morning predicted the name of the future bridegroom. In Denmark at Midsummer, two sprigs of St. John’s wort were set between the roof rafters of a house, and if they grew together there would be a marriage. In some countries, a plant of orpine was set on the windowsill of a young woman’s bedroom on Midsummer’s Eve. The next morning, its stalk would point in the direction from which her true love would come.

A method for dreaming true that can be done anytime, not just on Midsummer’s Eve, is to gather a bouquet of nine different kinds of flowers, one of each type. With the left hand, sprinkle them with oil of amber (i.e., oil in which an amber stone has been soaked). Then bind the blossoms to your forehead and get into a bed made up with fresh linen. You will be sure to dream true.

As it is traditional to burn nine kinds of wood for the Beltane fire, it is also a custom to throw nine kinds of herbs onto the Midsummer fire. Many of the herbs that were traditionally offered in this way have been mentioned above: St. John’s wort, rue, vervain, mistletoe, and lavender. The last one being an especially lovely incense. To these may be added feverfew, a daisy-like flower that, as the name implies, reduces inflammation; meadowsweet, which in ancient times was also called bridewort; heartsease, the tiny three-colored pansy; and trefoil.

There are several plants that in earlier times were called trefoil, and all were sacred to the Triple Goddess. Among these were oxalis (a type of sorrel), clover, and the shamrock. It is said that St. Patrick used the shamrock to demonstrate to the Irish people the three-in-one concept of the Christian trinity; but of course, the Tuatha de Dannan, the Children of the Goddess, were already familiar with the idea.

But it is the clover that is the trefoil of the Midsummer fire. Most clover leaves have three heart-shaped sections, but there is the rare and lucky four-leafed clover that, like the foliage of St. John’s wort, or the seed pods of rue, are the four part radial symbols of the Sun Wheel. The four-leaf clover is collected anytime as a lucky amulet:

One leaf for fame, one leaf for wealth,

One leaf for love, and one for health.

But if you find one with five, “let it thrive”; and if you find one on Midsummer’s Eve, offer it on the Sabbat fire!

The Nine Herbs Charm tells us something of the healing properties of certain herbs, and the nine herbs for the Midsummer’s fire tells us something about the magick of herbs. But they also tell us of the magick of the number nine. Nine is the number of completion. It is the last number of a cycle, the number ten being the beginning of a new cycle, or the same cycle on another level. Nine is also three times three, and three is a number sacred to the goddess.

The number one is the number of unity, it is often associated with the sun and the masculine principle in nature. It also relates to our stage in life as a newborn, and therefore to the sun and to the divine child. The number one, of course, is preceded by zero, a circle. The number one is symbolized by a circle with a dot in the middle.

The number two is a number of duality. It has been associated with the moon and its waxing and waning. It also corresponds to that stage in human development when we become aware of others. It represents the goddess and her consort, and all pairs of complements, balance, and harmony. The number two is symbolized by the solar cross.

The number three is sacred to the goddess and reflects her threefold nature of maiden, mother, and crone. For this reason, ingredients in a magick charm are often three in number and spells are repeated three times. The third time’s the charm. A triangle symbolizes the number three.

Four is the number of the earth plane, of the four directions: north, south, east, west; of the four elements: earth, air, fire, water; and of the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. It is also the number of the greater Sabbats, and of the lesser Sabbats. The number four is symbolized by the sun wheel or the square.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

A |

B |

c |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I |

|

J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

p |

Q |

R |

|

s |

T |

u |

v |

w |

X |

y |

z |

Letters of the Alphabet and their Numerical Equivalents

The number five is the number of man. It represents the five senses of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch; the five fingers of the human hand; and the five appendages, the two arms, two legs, and the head. It also represents the four elements of the number four plus spirit, which makes up five and all life, which is represented by the pentagram.

Six is a number of the goddess because it is a multiple of three, and it is often associated with the goddess in her aspect as a love and fertility goddess, Venus or Freya. The number six is the total of three and the numbers that precede it, one and two. This process of adding numbers together to better understand their significance is a practice much used in ceremonial magick, but seemingly forgotten in the natural magick of wicca and Paganism. It was, however, part of the magick of Pagan Europe because the practice of repeating a charm once, then twice, then three times (a total of six), is still a part of many an old European spell, as will be discussed later in this chapter. The number six is symbolized by the six-pointed star, among other things.

Seven is a mystical number, a number of spirit, and represents the various planes of existence, including the material or earth plane. It also corresponds to the psychic centers called chakras, which are associated with points along the central nervous system of the human body. The seventh, or the highest chakra, is receptive to the highest spiritual planes. The number seven also corresponds to the seven days of the week, and one week represents one phase of the moon, or new to the first quarter, first quarter to full etc., so that the number seven is also a number of the moon.

The seven days of the week are of great importance to ceremonial magicians, who recommended that certain types of magick be performed on particular days of the week, according to certain planetary influences. While we Pagans and wiccans may not be as concerned with planetary days and hours as we are with phases of the moon, it is important to be aware both of the Pagan origins of this tradition, and the names of the days of the week.

The first, of course, is Sunday, which is named for and sacred to the sun god, and the sun that symbolizes him. It is a good day for power magick, for health and vitality.

The second day of the week, Monday, is named for the Triple Goddess of the Moon, and this day is sacred to her. It is a good day for intuition and all sorts of magick concerning psychic ability.

Tuesday is named for the Anglo-Saxon and Norse god Tiew, an ancient father-god or spirit-father. Ceremonial magick associates Tuesday, or Tiew’s day, with Mars, but he is more closely linked with the Roman Jupiter or the Greek Zeus, the father of the gods. Among ancient languages, Z, D, and J are frequently interchangeable, so Zeus is Deus, meaning god. Jupiter is Zeus-Pater, meaning father-god. D and T are also interchangeable, so Deus becomes Tiew. Tiew’s day is best for magick associated with gifts from the gods, or the kind of money spells usually associated with Jupiter and performed on Thursday.

Wednesday is named for the god Woton, or Odin. Odin is a god of transformation and resurrection, and it is he who gives us the runes. Odin is also a shamanic god, and so his day, Wednesday, is perfect for all kinds of magick (especially shamanism), and anything dealing with the written word.

Thursday is named for the Norse god Thor, the god of thunder who, with his stormy nature and thunderbolts, superficially resembles Zeus. But he is really an ancient war god more closely linked with Mars and martial attributes of conflict, strife, courage, power, and victory. His day, Thursday, is more suited to magick concerning these things than is Tuesday.

Freya, the gentle goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, gives her name to Friday, traditionally a day of sorrow and tragedy. But this is probably due to the influence of the new religion and the events of Good Friday. For Pagans and wiccans it should be a day for love spells, fertility charms, and all acts of pleasure.

The seventh day is Saturday, named for Saturn, the Roman god of death and agriculture. As a god of death, it is suitable that he gives his name to the final day of the week. But Saturn is also the father of Zeus, and every ending is a new beginning. Saturday is perfect for magick dealing with new beginnings and firm foundations. Seven is represented by the seven-pointed star.

Eight is a number of power. It represents the sun and the eight solar Sabbats, the solstices and the equinoxes, and the turning points in between. It is symbolized by the eight-pointed star.

The number nine completes the cycle.

The letters of the alphabet also have numerical value which can be determined by using the chart.

The knowledge of numerology can be applied to the practice of magick in many different ways. For example, the number of herbs or candles to be used for a charm would depend on the kind of magick intended.

Other numbers that have great significance to Pagans and witches are thirteen, the number of lunar months in a year, and therefore the ideal number of witches in a coven; thirty-nine (three times thirteen), and one hundred and sixty-nine (thirteen times thirteen). These numbers are naturally all sacred to the goddess.

The time of the Summer Solstice is traditionally a time when charms and spells were performed for the purpose of protecting livestock and the barns in which they live, as well as the farmhouse. No one has done so more colorfully than the group of people who have come to be known as the Pennsylvania Dutch. These people, who migrated here in search of religious freedom early in the eighteenth century, include the Amish, Mennonites, Quakers, Lutherans, Reformed, and French Huguenots. Among the rolling hills of Lancaster and Lehigh Counties and the deep, haunted valleys of Burks County, they erected the enormous forebay barns, and cleared the fertile farms for their new homes; but they also brought with them from the old countries of the Rhine Valley a system of folklore, magick, and tradition that has been greatly overlooked by many on the Pagan path.

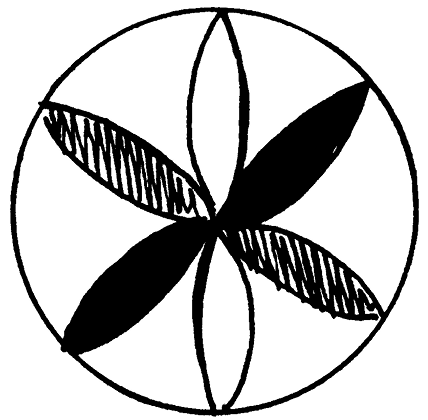

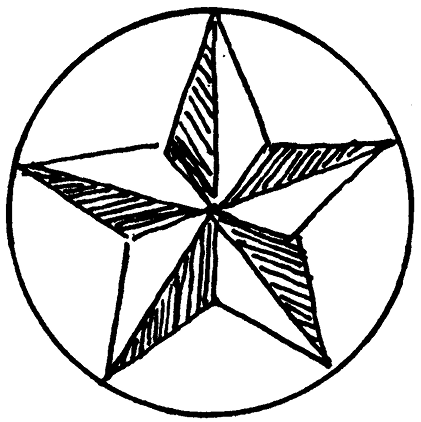

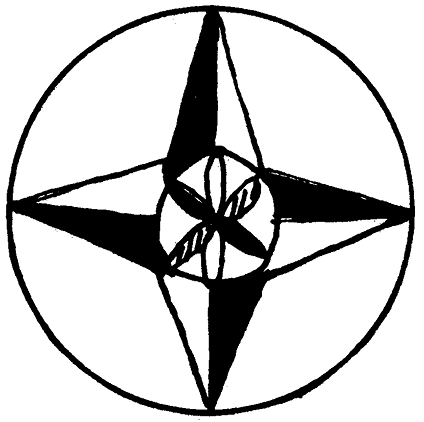

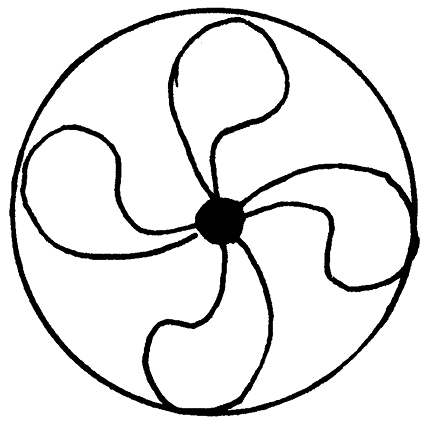

Probably the first thing that comes to mind when the term Pennsylvania Dutch is mentioned is the colorful and beautiful works of folk art known as hex signs. Incidentally, not all of the Pennsylvania Dutch use hex signs. The Amish and the Mennonites are plain folk who do not ornament their barns, their homes, or themselves. It is the Lutheran, Reformed, and others who produce these colorful rosettes enclosed in magick circles to protect their barns and livestock. These hex signs come in a colorful variety, almost as wide as the designs of the Pysanky, and each symbol has a specific meaning. The six-pointed rosette is for protection, and the five-pointed star enclosed in a circle—a sign more familiar to most Pagans—is a charm for good luck. A four-pointed star is a sun symbol, while the tear shape is a rain symbol. Oak leaves and acorns give strength of both body and character. The eagle, often two-headed, is also a strength symbol, while the distlefink or thistle-finch (gold finch) is a good fortune symbol. The eight-pointed star is for abundance. Hearts symbolize love, while “laced” hearts—those with scallops around them—insure love in marriage. Doves, unicorns, and tulips express virtues of peace, purity and faith, and hope and charity, respectively. Most of these symbols can be combined with others for more specific meanings. For instance, a sun symbol combined with a rain symbol would be a charm for fertility. Symbols can be repeated several times to multiply their power. For example, a five-pointed star surrounded by five additional five-pointed stars between its points is a powerful hex for luck and success.

Numbers, too, play a significant part in hex signs. Basically, three and multiples of it are feminine, while four and multiples of it are masculine.

But the most popular of all hex signs is the six-pointed rosette for protection. It is the basis of most other hex signs, and it usually forms the center of other designs. It is also based on a mathematical law which is one of the building blocks of nature: the relationship between the radius of a circle and the circle itself, as seen in beehives, ice crystals, etc. Here is how the six-pointed rosette is formed: using a compass, draw a circle of the desired size. Then, without changing the radius of the compass, make a mark anywhere on the circle. With the point of the compass on that mark, mark the circle with the radius. Then put the point of the compass on the new mark and mark the circle with the radius again. Continue this around the circle and you will find that the circle will be divided into exactly six parts by its own radius. Now, still without changing the radius, place the point of the compass on any one of the marks on the circle and draw an arc from one point on the circumference, through the center of the circle, to a point on the other. Continue doing this at each of the six points on the circle and you will have drawn a geometrically perfect six-pointed rosette, the basic hex sign. And this raises an interesting question. The name “hex” sign, of course, comes from the German word “hex,” meaning “witch” (today some Pennsylvania Dutch prefer the word “jinx”); but the hex sign is a six-sided figure, or hexagram, from the Greek word for six, yet there is no significant connection between the Greek hex for six and the German word for witch—or is there?

|

|

|

|

|

6-POINTED ROSETTE |

5-POINTED STAR |

4-POINTED STAR |

|

PROTECTION |

LUCK |

A SUN SIGN |

|

|

|

|

|

TEAR DROPS |

OAK LEAVES |

DISTLE FINK |

|

A RAIN SIGN |

STRENGTH |

PROSPERITY |

|

|

|

|

|

SUN & RAIN |

ROSETTE & HEARTS |

8-POINTED STAR |

|

FERTILITY |

LOVE |

ABUNDANCE |

The number six is a powerful number in the geometry of nature, and as the six-pointed rosette is the basis for most hex signs, so the rune “haglaz” (ninth in the Rune row) is sometimes referred to as the mother of all runes.

Not far from the Flying Witch Farm, among the wooded rolling hills and open farmland of Northhampton County, one hill stands out from all the rest. The name of this treeless rocky peak is Hexenkopf—The Head of the Witch. How this hilltop earned its name, and the mysterious power it contains, is a story that is closely linked to the hex signs of Lancaster County and is even less well known.

Along with the painted hex signs, the Pennsylvania Germans brought with them a system of healing magick called “pow wow.” In spite of its name, it had nothing to do with Native American practices. It is entirely Germanic. It is my belief that the term comes from the word “power,” because in the South those who have the ability or know some of the charms or incantations are said to have “the power.”

It is also almost entirely Christianized, almost—but not quite. Here and there among the charms, spells, and incantations, there are hints still to be discovered by the serious researcher of the great antiquity of this body of practice.

For example, an incantation from West Virginia to cure burns invokes the guardian angels of the four directions. Another, a cure for worms from Pennsylvania, states:

Mary, God’s Mother traversed the land

Holding three worms close in her hand.

The image of this Mother of God holding worms, or rather snakes, in her hands immediately brings to mind the Minoan goddess who holds snakes in her hands, as the word worm was often applied to snakes and serpents, and even dragons. A similar image appears even earlier in the goddess figures of old Europe, and a bit later on a stylized model of a funereal boat in a mound burial in Denmark, ca. 800 B.C.E. In this figure, a goddess is seated in the center of the boat with a snake on either side of her.

But the incantation continues:

One was white, the other was black,

The third was red.

These are the three colors—red, white, and black—which are traditionally associated with the triple goddess.

A remedy for fever begins with the words: “Good morning, dear Thursday!” and the instructions that follow explain that the charm must be begun on a Thursday. Thursday, of course, is sacred to the god Thor, and so the “dear Lord Jesus” invoked later in the same incantation was probably originally the god Thor.

HOW TO form the

six-pointed rosette

|

|

||

|

A CIRCLE DIVIDED |

AN ARC DRAWN FROM ONE POINT ON THE CIRCUMFERENCE TO ANOTHER |

A GEOMETRICALLY PERFECT SIX-POINTED ROSETTE |

|

|

||

|

HEXAGON |

HEX SIGN |

STAR OF DAVID |

|

|

||

|

HEXAGONAL CRYSTAL SYSTEM |

SNOWFLAKE |

HAGLAZRUNE |

When a researcher from the Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary was doing research on this form of healing in South Carolina, he came across a woman who used an incantation that invoked Thor. The incantation worked, much to the dismay of the researcher!

Aside from incantations, there are other instructions that link the practice of the Pennsylvania German pow wow to traditional wicca. For example, many of the charms must be applied three times, as in the saying “The third time’s the charm.” Usually a second application is made a half hour after the first, and a third one made one hour after the second.

Most incantations are followed by the practitioner making the sign of the solar cross in the air three times with the hand folded into a fist and the thumb held upward. So an incantation which repeats the magickal number of three times is accompanied by the Pagan sign of the solar cross, made the sacred number of nine times.

This marking of the solar cross with healing incantations is not confined to the Pennsylvania Germans. In England in 1528, Elizabeth Fotman was accused of Witchcraft and confessed that she took a rod and put it up to the horse belly that “was syke of the botts and made crosses on the caryers horse belly, and that the horse rose up and was hole.” Other women accused of witchcraft were also guilty only of healing animals with their charms.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, a book was written by a man named John George Hohman who lived in the vicinity of Reading, Pennsylvania. The book is entitled Pow Wows: The Long Lost Friend with a subtitle of A Collection of Mysterious Arts and Remedies for Men as Well as Animals. In it, Hohman states clearly that what cures man also cures animals (so the reverse might also be true). The book also states that anyone who owns the book and does not use it to save an eye or limb is guilty of the loss of the limb.

Another curious note in the preface states that the word “amen” at the end of an incantation means that the Lord will make come to pass that which was asked for. In other words, “so mote it be.”

Prior to the writing of pow wow, the charms and spells were passed down by word of mouth and never committed to paper, except in the case of a practitioner who knew too many charms to remember them all, and so wrote “papers” of them. The methods by which these incantations were passed on verbally is also purely wiccan. A practitioner (or “user,” as they were so called) was only permitted to transmit the knowledge to a member of the opposite sex, and only to three individuals in his lifetime. The penalty for violating these laws was the loss of “the power.” The first of these two conditions is based on the law of polarity and the flow of energy between opposites, a law that has largely been forgotten in recent years due to so much information being transmitted in the form of printed books. But when a charm is verbally transmitted form one person to another of the opposite sex, much more than just knowledge was given. This is why it is said that only a witch can make a witch.

The other part of this tradition, teaching the charms and spells only to three persons in a lifetime, reaffirms the almost forgotten law that states, “power shared is power lost”, one of the primary reasons for secrecy, even in pre-Christian times.

Hohman’s book is a collection of gypsy lore as well as Pennsylvania German pow wow and folk remedies, and really deserves serious study by anyone on the healing path.

Here are a few of my favorite remedies adapted for Pagan use: to prevent a person from killing game, speak the person’s name, and then say:

Shoot whatever you please,

Shoot but hair and feathers

And with and what you give

To poor people.

So mote it be.

Here is a charm for worms which begins:

Mary, God’s Mother [The Mother Goddess] traversed the land

Holding three worms close in her hand .

The charm ends with these instructions: “This must be repeated three times, at the same time stroking the person or the animal with the hand, and at the end of each application, strike the animal or person’s back, once at the first application, twice at the second, and three times at the third. Then set the worms a time to leave, but not more than three minutes.”

Some charms give the disease, or spirit of the disease, an alternative place to dwell. This is the secret of the Hexenkopf, the Witch’s Head. In the nineteenth century, near this unusual hill lived several pow wow doctors. The cabin of one of them still stands on a lonely knoll overlooking a wooded valley. All of these doctors, the Sailors and the Willhelms, used the hill called Hexenkopf as a vessel into which to drive the spirits and creatures of disease.

In ancient times, when tribes and clans gathered to celebrate the Sabbats, there can be little doubt that the telling of tales was a major part of the celebration. Particularly important were the tales that described the nature of the aspect of the deity being celebrated. These kinds of tales, which often come to be known to us in the form of myths and legends, tell us of a different kind of truth than historic truth, and of a reality other than physical reality. One such tale especially appropriate at the time of the summer solstice is the legend of King Arthur. From the Roman chroniclers of ancient Wales to the poets of the Victorian era, much has been added to the legend of Arthur, and these additions clarify rather than cloud the myth.

The historic facts about Arthur are simple enough. There was in fifth century Wales a warrior chief named Arthur, who twelve times met the Saxon invaders in battle, and twelve times was victorious. But the legend of Arthur, that is where history and myth come together, tells a much more important story. It tells the story of a Pagan Sun God.

Uther Pendragon, the rightful heir to the throne, in addition to his having just won it in battle, was filled with desire for the beautiful Igraine, wife of Gorolis. His friend and advisor, the wizard Merlin, agreed to help Uther to possess Igraine. Having had a vision of the coming of a king and a glorious future for the land, Merlin recognized his opportunity. He used his magick to shape-shift Uther into the likeness of Igraine’s husband, Gorolis. That night, as Uther and Igraine loved, Gorolis was killed at his encampment at Dilmilioc. At this time Arthur was conceived. His death/birth theme is a bardic type of formula used to indicate the divinity of the child.

In another version of this myth, Merlin and his master Bleys perform a spell to bring forth the infant Arthur from a storm tossed sea. The sea is a symbol of the Mother Goddess, and many an ancient God entered the material world by simply drifting ashore. But to some early Celts, the sea was also the site of the Underworld; so this myth suggests a return from death.

In Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, Arthur’s birth is surrounded by as much Pagan symbolism as is his conception, as Yule (i.e., the death of the old solar year and the birth of the new one) was the time chosen for Arthur’s birth. This repeats the death of the father/birth of the son theme basic to many Pagan belief systems, and in some Pagan traditions, represents the birth of the divine child—the sun god. Tennyson says:

And with shameful swiftness afterward

Not many Moons, King Uther died

himself, And that same night of the New Year

By reason of bitterness and grief

That vext his mother, all before his time

Was Arthur born.

The motif of the changeling or the kidnapped child in myth also usually indicates the child’s divinity.

Merlin hid Arthur away, or possibly left him in the care of a knight named Anton or Ector, who saw to Arthur’s schooling and welfare.

When Arthur was about fifteen years of age, he drew the sword from the stone, a feat that could only be performed by the rightful king. His kingship thus confirmed, Arthur was crowned. As king, he fought many battles and united the land. In one of these contests he shattered the sword that he had drawn from the stone. Merlin took him to the edge of a lake and an arm clothed in “white samite” appeared. It rose from the lake, holding aloft the jewel encrusted magickal sword, Excalibur. The sword was a gift from the Lady of the Lake, variously known as Vivian, Niniane, or Nimu. Arthur rowed out and took the sword:

The blade so bright that men are blinded by it—on one side

Graven in the eldest tongue of all this

world, “Take me” but turn the blade an ye shall see

And written in the speech ye speak yourself,

“Cast me away” and sad was Arthur’s face.

“What should I do?” Arthur asked. And Merlin said, “Take it, the time has not yet come to cast it away.”

Excalibur is, of course, Arthur’s sword or blade of power—his athame. But who is the Lady of the Lake? Traditionally, only the Mother can arm the son, but it is the Crone that bestows magickal power.

Arthur fell in love with Guinevere, daughter of King Leodogran. He sent one of his knights to fetch her to be his bride:

For that was later April, and returned

Among the flowers of May with Guinevere,

And before Britain’s stateliest altar-shrine the King

That morn was married while in stainless white.

Far shone the fields of May thro’ open door

The sacred altar blossomed white with May.

The Sun of May descended on their King

They gazed on all earth’s beauty in their Queen.

That the wedding took place in May suggests that this is a sacred wedding, of a god and a goddess. Celtic Pagan tradition held that during the month of May mortals were forbidden to marry. May was the month for sacred marriages, and June for mortal ones. The “Sacred altar blossomed white with May” refers not to the month, but to the white blossoms of the hawthorn tree with which Pagan altars were decorated at this time of year. The line, “The Sun of May descended upon their King,” reaffirms that Arthur represents a solar deity, and Guinevere as Queen of May represents the Maiden aspect of the goddess.

Following the wedding, the knights sang a song that began:

Blow trumpets for the world is white with May

Blow trumpets for the long nights have rolled away

Blow thro’ the living world—let the King reign!

This song would certainly suggest the celebration of victory of the sun god over the darkness of the winter months.

After the wedding, Arthur was given a gift of the Round Table by his father-in-law, Leodogran. The table had originally been designed by Merlin and could seat 140 men (or 150, depending upon the author). The Round Table is, of course, the Pagan’s Magick Circle.

Arthur gathered about him the Knights of the Round Table. A list of their names is given in the story of “Culhwch and Olwen” in the Mabinogian.

Here in the story of Culhwch and Olwen, the antiquity of the tale is attested to by the repetition of a bardic formula by Culhwch, the hero of the tale. He is told of thirty-nine tasks he must perform in order to win the beautiful Olwen. To each he answers, “It will be easy for me to get that, tho’ you think otherwise.” And each time his opponent replies, “Tho’ you get that, there are other things you will not get.” The magickal quality of this tale, and the identity of Olwen, are suggested by the number of tasks—thirty-nine, or three times thirteen—a number sacred to the goddess. Among the knights in this earliest tale of King Arthur’s court, there are a few familiar names like Kei and Bedwyr (Sir Kay and Sir Bedevere). Many of the names are possibly historic, and many of the knights have supernormal or shamanistic powers.

Lancelot, Galahad, and Percival are more recent additions to the legend, but even Lancelot has some of the earmarks of a deity. As an infant, he was snatched from his mother’s arms as she mourned over his father’s corpse on the battlefield.

Here again is the ancient Pagan theme of death of the father/birth of the son, as well as the changeling child. His abductor was Vivian, hence his name—Lancelot of the Lake.

In another tale, Lancelot must cross a sword bridge in order to reach Guinevere’s chamber. Like the rainbow bridge Bifrost in Norse Myth, the sword-blade bridge is a bridge to the Otherworld—and Guinevere, its Queen, a goddess.

One of the earliest of the knights associated with King Arthur is Sir Gawain. In the story of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain is invited by the Green Knight to take the first swing of the axe in a challenge; though Gawain succeeds in chopping off the Green Knight’s head, the Green Knight merely picks up his head and puts it back on his shoulders. Poor Gawain is then forced to keep the bargain they had made—to meet one year from this night, on the eve of the New Year, to give the Green Knight his turn to return the blow. The Green Knight represents the Holly King of the dying year (as is magnificently portrayed by Sean Connery in the lovely Stephen Weeks film, The Sword of the Valiant). While Gawain is likely to be a solar deity, the Oak King of the New Year. In Malory’s Le Morte D’ Arthur, Gawain predicts his own death will fall at noon, the hour when the sun’s strength begins to wane.

And so Arthur surrounded himself with knights, many of whom had supernormal powers and some of whom were earlier gods. King Arthur reigned and the land flourished and prospered because his powers were the powers of the sun.

The two most important objects in the tales of King Arthur are the sword Excalibur and the cup (cauldron) or grail. To Pagans, these symbolize the athame and the cup, male and female, god and goddess.

At one point, some of the knights went on a quest to find the Holy Grail, which according to Malory, was the cup which was used by Jesus at the Last Supper. Aside from Le Morte D’ Arthur, in the 1640s Thomas Malory also wrote A History of the Holy Grail, but the first actual mention of the Grail in connection with King Arthur is by Cretien de Troyes in 1180. According to Richard Barber in his introduction to Yvain, or the Knight with the Lion, “What Cretien himself intended by the Grail we may never know. Such evidence as there is points to a dish of plenty for which Cretien himself chose a rare French word ‘graal’ from the late Latin ‘gradalis.’ Such all providing dishes or cauldrons are fairly frequent in Celtic literature.”

In the tale of “Branwen, daughter of Llyr” in the Mabinogian, a cauldron is brought to Britain from Ireland by a pair of giant warriors. It has the power to bring warriors slain in battle back to life. In the tale of “Culhwch and Olwan,” handsome and generous King Arthur and his knights help Culhwch to obtain a magickal cauldron from the steward of the King of Ireland—one of his thirty-nine tasks. And, Taliesin became a wizard when he was touched by one drop of the brew from the Cauldron of the Goddess Cerridwen. One of the thirteen magickal treasures of Britain was the Cauldron of Dyrnwch.

Arthur had around him not only the bravest knights but also the wisest wizard—Merlin. Merlin is the Latin form of the Celtic “Myrddin,” and his story is as mystical as Arthur’s. During the Dark Ages, there was a King Vortigern who had usurped the throne, and who was hated by the people. He attempted to build a tower in which to protect himself, but the tower kept collapsing. He was advised by a court magician to find a boy child that had no father. This would end the problem. After years of searching he found a boy whose mother vowed that she had never known a man but was made pregnant by a spirit. The boy was Merlin, a child of the union of Spirit and Matter. (A Christianized version has it as the union of a demon and an unconscious nun.) Merlin told Vortigern that an underground lake was causing the tower to collapse, and that draining the lake would solve the problem. But when the lake was drained, there emerged two dragons—one red, one white—that engaged in a terrible fight. One killed the other and fled. An earlier version of this appears in the Mabinogion, in the tale of “Lludd and Llevelys,” a sun god imprisoned the two fighting dragons in a stone chest.

Inspired by the sight of these two dragons, Merlin developed the ability to prophecize. He predicted the death of Vortigen and eventually Uther attained the throne and fathered Arthur.

Geoffrey of Monmouth in his The History of the Kings of Britain, written in the early 1100s, credits Merlin with the building of Stonehenge. Geoffrey’s work is more fiction than fact, and it is he that first called Arthur a king. This linking Merlin to the pre-Christian Pagan shrine shows us that even then, Merlin was not believed to be of the new religion.

When he was one hundred years old, he began having premonitions of the end of Arthur’s reign. He also became involved with a beautiful young woman. But here things tend to get confused; some writers say she was Vivian, the Lady of the Lake. Others say that she was Arthur’s sister, Morgan le Faye. Whoever she was, Merlin eventually taught her a charm which would result in the death-like state of its victim. Tennyson says:

Then in one moment, she put forth the charm

Of woven paces and waving hands,

And in the hallow oak he lay as dead,

And lost to life and use and name and fame.

In some versions, Merlin is imprisoned in the hollow oak, while in others he is encased in an “island of glass.” The ancient pre-Celtic people of Western Europe buried their dead in hollowed oak logs, possibly because of the preserving qualities of the tannins in the wood; but more likely because of a belief in an Oak God and in an afterlife. (This idea bears stunning resemblance to an Egyptian myth in which Isis preserved the dismembered parts of her beloved Osiris in a hollowed tree trunk to give him eternal life.) The oak tree also suggests that Merlin was a Druid.

The island of glass may also lend itself to an interesting interpretation: according to The Atlas of Mysterious Places, “Glastonbury Tor was once almost an island for the sea-covered lowlands of Somerset Levels.”

“Glas” is a Celtic word meaning green or blue. “Tinne” is the Celtic name for holly, a sacred tree (but in ancient times the sacred tree was the evergreen oak). “Bury” means hill, so Glastonbury (glas-tinne-bury) means “Hill of Sacred Trees.” Possibly in ancient times there was a sacred grove on the Tor, which was then an island. An island of glas, then, would be the perfect place to keep the enchanted priest Merlin. Legend today holds that the summit of Glastonbury Tor is the entrance to Annwn—the Otherworld. And this is where Merlin waits for the spell to be broken.

The women in Arthur’s life are: Igraine, his mother; Guinevere, his wife; Vivian, The Lady of the Lake; and Morgan le Faye, his sister. Since Vivian and Morgan are also frequently confused, or their identities interchangeable, they can be considered one entity.

It is also Morgan/Vivian who brings about the end—at least for a time—of Merlin. Niniane or Vivian, the other half of this duality, gave Arthur Excalibur, the sword of power; the right to bestow magickal power also belongs to the Crone aspect of the goddess.

Robert Graves says that “le Faye” means “the Fates,” but faery is a better interpretation. She is certainly Morrigan the Celtic goddess of death. In an ancient French tale, Ogier the Dane, a knight of Charlemagne’s in his hundredth year, married Morgana the faery, who gave him back his youth. He lived for two hundred years in her Castle of Forgetfulness and then returned to the French court. There he wanted to marry another woman, but Morgana made him return to her castle. In this French version of the story of Merlin and Morgana, she most certainly is the same death goddess, and her Castle of Forgetfulness, Caer Arrianrod. But, above all, it is Morgan’s son Mordred who brings death to Arthur. According to the unknown author, known as the Gawain poet:

So Morgana the Goddess, she accordingly became

The proudest She can oppress

And to her purpose tame.

Igraine, Arthur’s mother, is most certainly the Mother Goddess. Guinevere, Arthur’s bride in May—goddess of love and beauty—is the Maiden. And his sister, the dark enchantress Morgan le Faye, is the Crone. All the women in Arthur’s life are aspects of the Triple Goddess.

The final symbolic episode in the life of King Arthur is its conclusion by death in a battle after a reign of thirty-nine sacred years. The night before the battle, Arthur had a dream. According to Malory:

King Arthur dreamed a wonderful dream, and in him

[the dream] seemed

he saw upon a scaffold a chair, and the chair was fast to a

wheel, and thereupon sat King Arthur

in the richest cloth of gold

that might be made.

As the dream went on, the wheel turned so that the chair was up side down, and the king fell into “an hideous black water and therein were all manner of serpents.” Initially, the symbols are obviously sun symbols—i.e., the solar wheel and the “richest cloth of gold.” And then the king or solar deity falls from his throne into darkness at the turning of the season.

The foe that Arthur is to meet in battle at daybreak is Mordred, son of his sister Morgan le Faye. According to some authors, including Malory, Mordred is also Arthur’s son. There is a wonderful scene in the outstanding 1981 British film Excalibur (starring Nigel Terry), in which Morgana uses Merlin’s magick to shape-shift into the likeness of Guinevere so that she may trick Arthur into begetting Mordred. The battle, according to Malory, takes place in Salisbury. What more perfect place for the ritual death of the sun god than at this ancient temple of the sun?

According to Tennyson, the battle was fought at Lyonesse. The “Lost Land of Lyonesse” is traditionally said to have been between Land’s End in Southwestern England and the Scilly Is. This is the westernmost point of Southern England. And since West is where the sun sets, and the western point on the circle in the wiccan-Pagan tradition symbolizes death, it is a most appropriate site for the death of the sun god.

The morning of the battle dawned dense with fog, and many were killed on both sides. Arthur received a fatal wound from Mordred, and at the same instant Excalibur struck its final blow killing the king’s nephew/son.

Then, according to Malory, Sir Bedevere carried the wounded king to a nearby ruined chapel. We could take this to mean Stonehenge, which in Malory’s day was understood to be a Pagan temple, and was even more of a ruin than it is today.

Arthur asked Bedevere to take Excalibur to a nearby body of water and cast it in, and to come back to him and report what happened. Twice Bevedere had not the heart to throw the sword into the lake, but the third time he did. And an arm “clothed in white samite” rose from the lake to grasp it—brandishing it thrice before disappearing beneath the waves. When Bedevere reported this to Arthur, the King asked to be carried to the water’s edge.

“Then saw they how there hove a dusky barge,” and on the deck of this barge, “Black-staled, black hooded, like a dream, three queens with crowns of gold.” And the dying king’s body was placed on the barge in the laps of the queens, to sail—

To the Island-Valley of Avilion

Where falls not hail, nor rain, or any snow,

And bowery hollows crowned with Summer see,

Where I will heal me of my grievous wound.

This most certainly is the Pagan Summerland, the three queens the triple goddess, and the barge at once a symbol of the goddess and the solar boat.

“And then the new sun rose, bringing the New Year.”—Tennyson.

And Malory says, “And many men say that there is written upon his tomb this— Hic jacet Arthurus, Rex qoudem, Rexque futurus.” Here lies Arthur, Once and Future King!

Early Celtic Christians saw in these ancient tales reflections of their own beliefs, and in the promise of the return of Arthur they saw the Second Coming. And this is not surprising because the roots of the new religion also grew out of the Pagan past.

The historic facts—whether Arthur actually was king, or if he really existed—are irrelevant. What is important is that here we have a tale that has been told and re-told. Bards have sung it, poets have put pen to it, and Hollywood has put it on film. It is the tale of a child born at the New Year. He becomes king and weds the queen in May. He reigns and the land flourishes; then his reign declines , and on the eve of the New Year he is killed by his sister’s son.

To look at a legend for its historical truth is to look through the wrong end of the telescope. The Legend of King Arthur—Once and Future King—is not the story of a king who died, but of a God reborn, and the promise of life renewing itself.

The warm, dry afternoon of June invites walks in quest of magickal herbs, along sunny country lanes, past fields of new mown hay drying in the sun, and in the shaded forest where lady’s slipper orchids and faery candles grow. Mentally, we mark the location of the herbs that on Midsummer’s Eve will be ritually gathered, to be offered on the Sabbat fire or hung as amulets for protection. As the lengthening days of June darken into honeysuckle-scented nights that twinkle with fireflies, we begin to prepare for the Sabbat rites.

Of all the solar Sabbats, this is the one that marks the greater glory of the sun, and so it is appropriate to have a sun symbol as a focal point within the Midsummer circle. In ancient times, the sun was portrayed in various ways by different cultures. The ancient Egyptians depicted it as a great gold disc carried on its daily voyage by a celestial boat. To the ancient Greeks, it was drawn in the solar chariot, and later personified as Helios, the god of the day, as Sol, and eventually as Apollo, god of the sun and brother to the moon goddess Artemis. By Northern Europeans, the sun was visualized as a great golden disc carried on the back of horses, and later came to be personified as Balder. But one of the most powerful and universal sun symbols of all is the solar cross contained within a circle, or solar wheel. This solar disc or sun wheel can be made out of a variety of materials. One of the simplest is made of grape vine. Vine that has been pruned in March is still flexible enough to be bent into a tight circle, wound around two or three times with the ends tucked around to the back. Once the circle has been formed, two short lengths of vine, a little longer than the circle is wide, can be used to form the cross. Place one length horizontally across the back of the wheel. Then, place the vertical length behind that one so that the lower end is in front of the circle, and bend it gently forward so that the upper end is also in front of the circle, locking everything in place.

This sun wheel can then be adorned with streamers of yellow ribbon, bright yellow flowers, or symbols of the four elements: e.g., bird feathers for air, a stone for earth, sea shells for water, and Yule log ash for fire. It has become our tradition here at Flying Witch Farm to hang the solar disc in a rowan tree over the altar of stone in the woodland wildflower garden after the Midsummer rites, and to burn the old one on the Midsummer fire.

This is the time of year when birds that have built their nests and laid their eggs begin to molt their feathers. Since ancient times, feathers have been collected for magickal uses, and one of the most famous charms using feathers is the Witch’s Ladder.

To make a Witch’s Ladder, first braid together three different colored yarns three feet long, the colors depending on the type of magick you wish to work. Enchant the cord as you braid it with words like:

Yarn of red, black, and white

Work your magick spell this night

Then take nine feathers—all different, or all the same, or a combination, again depending upon the type of magick. One at a time, tie each feather onto the cord with a knot, saying words like:

With this feather and this string,

Protection to my home I bring.

When all nine feathers have been tied onto the cord, tie the ends of the cord together to make a circle, consecrate it, and hang it high in your home or wish tree.

In ancient times, livestock was driven through the embers of the purifying Midsummer fire after the flames had died down. Today some traditions are reviving this ancient ritual. One safe way to do this is to build a second fire from the first one, leaving a safe path between the two, to walk or drive livestock through. An even safer method is to gather some of the ashes after they are cool and rub them on the animals, making the sign of the solar cross.

If this sounds like a Yule log tradition, remember that the Midsummer fire of June and the Yule log of December stand across the Wheel of the Year from one another, one marking the moment of the sun’s greatest power just before it begins to wane, the other marking the moment when the sun ceases waning and begins to grow in strength and power—and the solar year, the divine child, is born anew.

Whether you are planning to drive a herd of cattle through the Sabbat fire, or just a beloved pet and familiar, it is traditional to kindle the Midsummer fire with two kinds of wood, oak and fir. Originally, this Sabbat fire was lit by the friction of these two woods. This combination of woods can be interpreted as representing the god and the goddess, the oak being the sun king and the fir the moon goddess, united in the element of fire. Even if the Sabbat rites are held indoors, and the fire is kindled in a cauldron, these two kinds of wood should be present to lend their special magick to the celebration of the season.

About this time of year, the warm, dry hay-scented breezes of early June become the hot, oppressive stillness of high summer. The buzz of insects and the roll of distant thunder are all that break the quiet of the afternoon hours, and many of us seek the cool of the mountain forests or the refreshing ocean breezes. As we plan our summer trips it is a time to remember that the traditional magick of Midsummer places an emphasis on the protection of animals, not only of beloved pets and faithful livestock, but of those wild creatures who are likely to cross our path when we venture out in our cars and RVs. So this is a perfect time to cast a spell of protection around your vehicle so that it will not become a vehicle of harm to any living creature.

Obviously, this ritual will have to be performed in your driveway, so it might be wise to make it appear to be part of a traditional Saturday afternoon car washing ritual. Suds and hose the car if necessary, then asperge it with salted water walking sunwise around the car, all the while imagining any negativity being washed away. You might say words like:

I purify you with this water

So that you will not be a weapon of harm.

Use the car’s name if it has one (our vehicles do). Then when the car is dry, anoint the headlights, front bumper, front fenders, grill, hood, tires, any part of the vehicle you can imagine colliding with an animal, with a protection oil (pure olive oil in which herbs of protection, such as those mentioned earlier in this chapter, have soaked). Finally, anoint the hood ornament, or whatever passes for one on your car (these serve the same function as figure heads on ancient ships, to look out ahead of the vessel) saying words like:

Lord Faunas, I ask for your protection

God of the wild creatures

Let not this car of mine

Be a weapon for destruction,

As I will, so mote it be!

When the magickal herbs have been gathered, the Witch’s Ladders have been hung, and the Midsummer fire has died to ashes, the warmth and joy of the solstice Sabbat will linger until Lammas. Meanwhile, as the light of the sun wanes its heat intensifies, ripening the first sweet strawberries, then fragrant raspberries. The white, round heads of cabbages swell, and the strangely scented vines of the tomatoes begin to set fruit. The hazy heat of the summer afternoons drive sheep and dairy cows alike to seek the shade of trees, and other creatures more secretive only venture out at night. By day the toad is hidden from the sun, and snails and slugs leave only silver trails to be found in the light of day. And all the while the grain, still green, ripens in the fields in preparation for the sacrifice of the harvest.