In Uzbekistan on the Amu Darya, not far from the mouth of the Surkhan Darya, lie the ruins of the important medieval city and fortress Termez, sometimes transcribed from Persian as Tirmidh. There are three different sites of the city. Old Termez, situated immediately on the riverbank, was destroyed by Chingiz-Khan. A settlement was already on this site in ancient times, mainly because an island in the river and a shallow bed offered an easy crossing.

We reached Termez, a large town with fine buildings and bazaars and traversed by canals. It abounds in grapes and quinces of an exquisite flavour as well as in flesh-meats and milk… The old Termez was built on the bank of the Oxus, and when it was laid in ruins by Chingiz, this new town was built two miles from the river.1

This town still existed under the Uzbeks. In Timur’s time the ford was so important that a permanent floating bridge was kept here and tolls were levied from caravans and travellers who crossed it. The third site is that of the present city, which lies on the intersection of the Bukhara (Kagan)–Dushanbe railway line and the highway from Samarkand to Afghanistan. A modern bridge, a few miles upstream, paradoxically called the ‘Bridge of Friendship’ served the Russian army in its invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

Clavijo, the Spanish envoy to Timur, has this to say about Termez:

We crossed the Oxus and in the evening of the same day we entered the big city of Termez. Previously it was part of Lesser India [i.e. Afghanistan], bur Timur made it part of Samarkand. The country of Samarkand is called Mongolia and the language here is Mongolian. Some of the Oxus people speak Persian and cannot understand it. These two languages have hardly anything in common. Even the script used by the Samarkandians is different from Persian and those on the south bank cannot read it currently.

By this Clavijo means the Uighur script, which the Mongols took on after their victory over the Uighurs. It was of Syriac origin and was brought to the Uighur country, east of the Tien-Shan and south-west of Lake Baikal, by the Nestorian monks. The Persians at that time used Arabic script, as they still do.

Clavijo also noticed one extremely interesting detail when crossing the river:

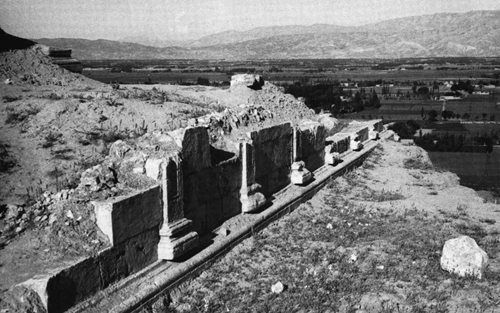

Fig. 24 Amu Darya and Zarafshan

Nobody may cross the Oxus from north to south without a special permit or laissez-passer. In this must be stated who he is, where he comes from and where he goes. Even a free man who was born in Samarkand must have such a permit. On the contrary everyone who wants to enter Samarkand, may cross the river freely and does not need anything.

The reason for this ingeniuous arrangement was obviously to keep people in the country and prevent them from escaping abroad.

The city of Tirmiz is vast and very populous; it has no walls and is not fortified. And it is enough to say, that the inn where they accommodated us was so far from the entrance of the city, that we were quite tired before we arrived there.2

Belenitsky3 regards the name Termez as a distortion of the name of a Graeco-Bactrian king, Demetrius. The existence of the city in the Graeco-Bactrian period seems to be confirmed by many coins and other objects from that time that were found in the ruins. A thorough excavation of levels belonging to the period has so far not been possible, because they lie at a considerable depth under later levels.

However, an important discovery must be mentioned here, although it was made 8 miles upstream from the town, near the village of Ayrtam. In 1932 a carved slab of limestone was found in the water, and in 1936 seven other fragments were unearthed during excavations of a Buddhist shrine. All fragments, now in the Hermitage, belong to a frieze that dates from the Kushan period (first or second century AD) and shows, in high relief, figures of male and female musicians and bearers of offerings. Each figure is framed in acanthus leaves. The site was excavated in 1964–66. It seems that in the second century BC there was a fortified Greek outpost, while in the first and second centuries AD a Buddhist cult complex was built with a sanctuary, a stupa, and some auxiliary buildings. A burial site nearby dates from the second to the first century BC.

Much valuable material belonging to the Kushan period was discovered in Termez itself, in particular a Buddhist cave monastery on the hill of Kara-Tepe, in the north-western corner of the ancient city. The distinctive feature of this short-lived building complex of the early Kushan era is that it was mostly hewn out of rock, an Indian characteristic quite exceptional in these areas. It is, in fact, the only site of this kind so far discovered in Transoxania. In addition to badly preserved wall paintings there were plaster reliefs and statues and also fine thin pottery with numerous inscriptions in ancient Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. Similar inscriptions were found in Balkh and Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan.4

In the ruins of the medieval, pre-Mongol, city we find the group of buildings around the mausoleum of Abu Abdullah Muhammad ben Ali Tirmidhi, called Hakim al-Termezi, who died in the year 869. (See 49 and colour plate 10.) The mausoleum itself was built towards the end of the ninth century. The present building dates mostly from the twelfth century and is built of unbaked bricks; baked bricks were used as tiles on the outer walls only. On the western and southern walls some ornaments in incised stucco were preserved. Above the cenotaph, a domed ceiling is decorated by some Zoroastrian motifs, circles with symbols of the sun and ornamental vases between them. The cenotaph itself is of white marble or of limestone resembling marble, richly carved. It was donated by Ulugh-beg in the fifteenth century. Next to the mausoleum is a small mosque, which, in the eleventh century, was merely a wall with a cylindrical mihrab. This too was originally covered with ornamented bricks, but after a reconstruction received a much more elaborate decoration, both architectural and ornamental. The entrance to the mosque is through a khaniga, a domed brick building dating from the Timurid period.

The palace of the rulers of Termez, of which only a number of decorated slabs and panels have survived, was built perhaps in the eleventh century, but not before 1035. The original decoration, again mainly of bricks, was thoroughly altered at the turn of the twelfth century. The palace consisted of a large number of buildings round a courtyard; opposite the entrance was an iwan, a large open reception hall with three walls, open on the fourth side; on the walls were three parallel rows, or bands, of ornamental panels, one above the other. The bottom one consisted mainly of medallions in small arches and the middle one of girikhs. In the top one we find both girikhs and medallions on the columns, and on the walls, between the curves of the arches, some pictures of fantastic animals. Incised alabaster was also applied inside the arches, on their fronts, on the corner columns and on the stalactites. The variety of ornamental motifs is enormous. Some fragments of wall paintings have also been found. The colour scheme and the design was most probably similar to that of the alabaster stucco.5 The outer walls of Termez date probably from the beginning of our era. In the ruins of the medieval, pre-Mongol, city, the archaeologists have recently uncovered a house from the tenth and eleventh centuries built of unbaked bricks with column bases of stone in the central room or patio.

A huge fortress was found in the vicinity or Termez and excavated by a French-Uzbek archaeological team from 1993 onwards. The site, dated to the first to the third century AD, was a fortified urban settlement around the mound of Chinghiz Tepe, with a number of religious buildings of a pre-Buddhist dynastic cult and Buddhism. There was a stupa with some Graeco-Buddhist decorative elements, a hall with columns and a monumental entrance. At the top of the mound the ruins of an important building are being excavated. The medieval citadel in fired bricks lasted until the twelfth century, when it was destroyed by Chinghiz Khan. Thanks to its position on the Silk Road, the site that was originally a small Greek military outpost, became an important commercial and religious centre surrounded by several Buddhist communities and monasteries, such as Kara Tepe and Fayaz Tepe (see below).6

Ten miles north of Termez lies the site of Balalyk-Tepe, a Soghdian fortress, which existed probably until the Arab occupation. It was a small building, 100 square feet, standing on a mound some 20ft high and containing fifteen rooms. Most interesting of these is a square reception room in the centre, approximately 16 square feet, with benches all round. Some interesting paintings were found on the walls, dating from the sixth to the seventh century.

All paintings are devoted to the same theme – a ceremonial banquet in which a large number of people are taking part. The paintings on three walls contain 47 figures of men and women, wearing splendid garments patterned in many colours. In the foreground are the banqueters in a variety of attitudes, either sitting with crossed legs or in a semi-reclining position. Behind them on a smaller scale are the serving girls. The clothing and various articles they hold in their hands are painted with astonishing care and delicacy. The men wear closely fitting caftans with a broad lapel on the right breast; the women wear sleeveless cloaks thrown loosely over their shoulders. These garments are made of brightly patterned fabrics which show great variety of design.7

The paintings of Balalyk-Tepe and carved wood and clay reliefs from DzhumalakTepe are considered by Rempel to be the most outstanding art specimens of that period (sixth and seventh centuries). He sees, for instance, in the ornaments on the garments some important motifs, little palmettes, hearts, crosses and circles enclosing human and animal heads that later played a significant role in European and Middle Eastern heraldry. In spite of some Buddhist elements, the wall paintings and the objects found in Balalyk-Tepe do not seem to relate to Buddhism but more probably to a blend of various creeds and forms of worship.8

Sixteen miles north-west of Termez is Zar-Tepe, where coins from Greek Bactria to the Hephthalites, as well as pottery from the third century BC to the fifth or sixth century AD were found. The site was excavated in 1979–81; a walled chapel was constructed on top of a Kushan one that was apparently abandoned at the time of the general decline of Kushan settlements at the end of the fifth and the beginning of the sixth century AD. Zang-Tepe, 20 miles north of the city, was a fortified castle founded in the first century BC and rebuilt at the end of the fifth century AD. Among other interesting finds, like glassware and pottery of the seventh and eighth centuries, were numberous Buddhist texts written in Sanskrit on birch bark a millimetre thick, in a variant of the Brahmi script. Dzhumalak-Tepe and Zang-Tepe are Soghdian forts of a similar type to Balalyk-Tepe. They were basically the dwelling and farmstead of a landowner and were built, for security reasons, on an artificial mound or podium (stylobate). Such castles, or kushks as they were called, were the most typical feature of Central Asian architecture of the Soghdian period. They usually stood in the centre or on one side of a rectangular platform on top an artificial mound of clay. The kushk itself contained either a number of rooms alongside each other on both sides of a narrow corridor, or grouped around a central hall with a cupola, which later became known as the mehman-khana, or reception room. In the walls were usually some narrow loopholes. From the outside, the kushk looked like a massive rectangular fortress. The walls were reinforced with half-columns or half-turrets and towered high above the truncated pyramid of the base.9

A typical example of a Soghdian kushk is Kirk Kyz, a few miles north of Termez. (See colour plate 16.) The so-called Zurmala Tower, 51ft high, is believed to have been a Buddhist stupa dating from the first century BC or the first century A. Fayaz-Tepe, also north of Termez and recently excavated by L. Albaum, was a late Kushan Buddhist monastery. A courtyard, the monastery buildings around it and the remnants of a stupa can be seen.

The two mausoleums of Sultan-Saadat near Termez also date from the eleventh or twelfth centuries. They stand alongside each other, built on a square plan, and are joined by a fifteenth-century iwan (portico) with a high frontal wall. The northern mausoleum (eleventh century) is better preserved. Its decoration is strictly architectural, both outside and inside, but some ornamental details may be found on the corner columns and in the arches. They are engraved and incised in simple baked bricks, and mark an important step towards the technique of incised terracotta later widely used all over Central Asia.

West of Termez, in the region of the Kuhitang mountains, are several Paleolithic sites containing rock engravings (Zaraut-Say, Zarauk-Kamar etc.).

Following the road west from Termez along the Amu Darya, we come to town of Kelif. This, according to Arab geographers, was about two days’ journey from Termez. In the tenth century, Kelif was situated on both banks of the river and was thereby distinguished from all the other towns along the banks of the Amu Darya. The main portion of the town, with the mosque, was on the left bank. The road from here to Bukhara ran, as it still does, through the Kashka Darya valley. Below Kelif was the town of Zamm, and from here, along the left bank, the waters of the river were used for artificial irrigation. The uniformly cultivated tract began, according to Barthold10 from Amul, the present-day Chardzhou. This town, now an important railway junction on the line from Tashkent to Ashkhabad and Khorezm, was, in the Middle Ages, situated on the caravan route from Transoxania to Khorassan (which the present railway line roughly follows). Where now there is a railway bridge, there used to be the most important ferry across the Amu Darya, more important in some periods than the Termez ferry.

East of Termez, on the Kafirnigan River, on the territory of Tajikistan, lies the small town of Kobadiyan, near which one of the most famous treasures of all time, the so-called treasure of Oxus was found in the late 1870s. This was a considerable hoard of objects dating mostly from the Achaemenid period, and now in the British Museum. Unfortunately nothing is known of the circumstances in which it was found, and experts hold different views about its origin. Some archaeologists believe that this was not a hoard of golden objects imported from Persia, having all been found in one place, but the result of continuous looting. Moreover, it cannot be ascertained that the present collection includes everything that originally belonged to it. In 1877 most of these objects appeared on the markets of Bukhara, from where they gradually found their way to the bazaars of Peshawar and Rawalpindi and finally to London.

55 The Mausalla, Herat. Minaret

56 Guldara stupa

57 Citadel Bala Hissar, Herat

58 Shahr-i Zohak

59 The stupa, Haibak

60 Remains of central sanctuary, Surkh Kotal

61 The ‘large’ Buddha, Bamiyan

The site of Kobadiyan itself became a centre of archaeological interest in the 1950s. Two sites were found on which ancient settlements existed and land was extensively irrigated from the seventh to the fifth century BC. The level called Kobadiyan I (seventh to fourth century BC) was mostly found at Kala-i Mir, and Kobadiyan II (third to second century BC) at Kei-Kobad-Shah. Kobadiyan III (first century BC to first century AD) coincided with the period of the Graeco-Bactrian Empire, and Kobadiyan IV (second century AD) was contemporary with the reign of the Kushan king Kanishka. Grey-ware pottery and small human and animal figures are characteristic of Kobadiyan III, while red-ware pottery prevailed in Kobadiyan IV. In the last period (third to fourth century AD.) not only pottery but also some coins were found.

In Kala-i Mir, an ancient Bactrian dwelling from the seventh to the sixth century BC was discovered; the pottery here was similar to that of Giaur-Kala (Merv), Samarkand-Afrasiyab and Bactra-Balkh. Kei-Kobad-Shah was a fortified place, inhabited continuously from the third or second century BC until the fourth or fifth century AD. Bases of columns and Corinthian capitals with clear Hellenistic influence were found here.

Of the kurgans in the Kobadiyan region it is possible to distinguish between the tombs of the nomadic tribes responsible for the collapse of the Graeco-Bactrian Empire, those of the Kushan period, and finally the post-Kushan tombs. In contrast to the usual practice of burying the corpses, some tombs indicate that the corpses were incinerated. This suggests that some later tribes, possibly the Huns, crossed the region in the fourth and fifth centuries AD on their way to Afghanistan.11

Still further east, on the Vakhsh River, the biggest tributary of the Amu Darya, 11 miles from the town of Kurgan-Tyube, is the site of the Buddhist monastery of Adzhina-Tepe. This is the most important Buddhist monastery so far discovered in Central Asia. Excavations of this mound (approximately 33ft by 150ft) have been going on since 1960. As described by Belenitsky,12 the monastery consisted of two equal halves, each 150 square feet, joined by a gangway. Each half was built on a four-iwan plan. In the south-eastern half there was a courtyard, in the north-western half was a stupa, while the monastery proper was in the south-eastern part. In this were the temple buildings, cells for the monks, a large hall or auditorium with an area of over 1,000 square feet, and various offices. The different parts of the structure were linked by corridors running round the inside of the perimeter. The stupa was surrounded by an outer structure consisting of corridors, small shrines and a number of small chapels, each with an iwan opening towards the stupa. The entrance, in the middle of the south-east side, consisted of a double iwan facing in opposite directions linked by an arched opening. The whole structure was built in large blocks of pakhsa and adobe bricks; the long buildings and the corridors had vaulted roofs, yet the square buildings had domed roofs, and the auditorium and temple apparently had flat wooden roofs. Here, too, remains of paintings and sculptures were found. The walls and ceilings of the buildings round the stupa were probably decorated with paintings, and those in the monastery half of the complex too, but only negligible fragments were preserved on the walls; most fragments of painted stucco-work were found in the rubble on the floors. The clay sculpture was better preserved; all the paintings and sculpture were on religious themes (pictures of Buddha, bodhisattvas, monks, demonic beings etc.). The largest piece is a figure of a reclining Buddha, 40ft long, dating from the fifth century AD, and similar in size and style to the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan. It can now be seen in the museum of Dushanbe. Some symbols engraved in the ceilings of man-made caves are reminiscent of those in the Buddhist caves of Bamiyan. All the statues were moulded from clay without any reinforcement, and remains of original colouring can be seen.

In 1954 the fortified building compound of Kukhn-Kala, of the Graeco-Bactrian period, was found near the town of Voroshilovabad. Bronze objects and high-grade pottery dating approximately from the end of the second and the beginning of the first millennia BC were found in tombs in the lower Vakhsh region where the Rivers Vakhsh and Kyzylsu join the River Pandzh (upper Amu Darya).

Stone Age and Bronze Age sites were found in abundance in the Pamir mountains in the region of Upper Badakhshan. The area is accessible by road only in the summer months, either from Osh in the north or from Khorog in the west. Paleolithic and Neolithic industries appear to have frequently coexisted here, and distinguishing between them is sometimes difficult.13 The Paleolithic finds in the eastern Pamirs comprise the Shakhty Cave, with interesting rock carvings, among which was a human figure with a bird’s head. The rich Neolithic finds were near Lake Rangkul, north of the Murghab and Aksu Rivers, in Markansu (the Death Valley), north-west of Lake Karakul, and at Osh-Khona, which yielded the richest collection of Neolithic tools found so far in Central Asia.14

A great many kurgans were explored after 1946, the oldest of them being the Saka tombs in the eastern Pamirs. They yielded a mass of information on the burial rites of the population, which was most probably nomadic. The finds date mainly from the sixth to the second century BC, and contain bronze objects, ornaments, jewellery in bronze with semi-precious stones, and also rather clumsy bronze figures of animals reminiscent of the Scythian animal style.

The valley of the Surkhan Darya, north of Termez, represents another region rich in finds of all archaeological periods. In the extreme north, in the Hissar Range, Neolithic finds have enabled the so-called Hissar culture to be named. The material here is entirely of stone, a grey conglomerate, with a small amount of flint. Floorings have been discovered made of a mixture of plaster and ashes, with the bases of large pots or jars set into the ground. The main occupation of the inhabitants was hunting, but some traces of primitive agriculture were also found.15 Near the town of Denau there are two sites dating from the Graeco-Bactrian period: a large town site, Dalverzin-Tepe, and a smaller one, Khaydarabad-Tepe. At the village of Shahrinau, near Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, a site with an area of 860 acres has been discovered. None of these three sites has so far been systematically explored.

Near the mouth of the river lies one of the most important sites of the Kushan period. It consists of a group of separate mounds near the village of Khalchayan and dates from the first century BC to the second century AD. A small, wellpreserved building discovered in one of these mounds was rectangular in plan. It consisted of a five-bay hexastyle iwan, an oblong hall behind it, another room with two columns and several adjoining apartments with linking corridors – a total of eight rooms.16 Stone bases were found here for the wooden columns that had supported the roof beams, and also fire-baked tiles, antefixes and stepped merlons from the roof. Apart from pottery, various utensils and coins, there were some interesting fragments of clay sculptures representing an important stage in the development of local art. There were several subjects – a frieze with gods, goddesses, girls, musicians and dancers; a group of statues consisting of a seated king and queen surrounded by their family; and yet another group of figures that suggest they were portraits of particular persons. Horsemen form a separate group, with horses in full gallop and riders clad in closely fitting belted tunics, trousers and soft-soled boots, and probably armed with bows and arrows. Some of them were in bas-relief. but most in high-relief or almost fully in the round. These horsemen recall the figures of Parthian cataphracts (cavalry) in Dura Europos, and also fit into Plutarch’s description of the Parthians who fought against the Romans at Carrhae in 63 BC.17 As for style, the sculptures of Khalchayan represent an early stage of the so-called ‘dynastic style’ – as opposed to the temple art of Buddhism – and are closely connected with the Parthian art of Nisa.

Also in the Surkhan Darya region, there is an interesting minaret in the village of Dzhar Kurgan. It is dated 1108–9, built on an octagonal base, and formed of twenty-four half-columns or ribs, larger at the base and narrower at the top. Originally, the minaret was much higher, but the top part, just above the band of ornamental inscriptions, has disappeared. The half-columns are decorated with simple brick ornaments that belong to the same style and same architectural school as other outstanding minarets from that period (Kalan in Bukhara, Vabkent) in Central Asia and, somewhat later, in Delhi, Khorassan and elsewhere.

The excavations at Takht-i Sanghi (see also p.206) where the famous Oxus treasure was found, started in 1877 and continued sporadically until recently when they had to stop because the site was included in a military zone. It is a small hillock near the confluence of the Vakhsh and the Pandzh, which from here acquire the name of Amu Darya. A Zoroastrian fire temple was unearthed which was thought to be the biggest in ancient Bactria. Some 8,000 objects were brought to light which had mainly been used for sacrificial purposes. Hellenistic ivories, a number of gold vessels, carved bone reliefs, coins and jewels similar to those found in the fortress of Hissar in the west of the country and dated from the fourth to the third century BC, are now exhibited in the museum of Dushanbe.18

Another interesting site in the south of the country was excavated in 2001, close to the regional centre of Kulab. A pottery workshop from the Achaemenid period was found here as well as two tombs and traces of walls and paving, indicating that this was the site of a large settlement the size and importance of which has still to be ascertained.

Full details of abbreviations and publications are in the Bibliography

1 Gibb, Ibn Battuta, pp.174–75.

2 Le Strange, Clavijo, pp.201–2.

3 Belenitsky, Civilisation, p.74.

4 Frumkin, CAR XIII, p.242.

5 The sites of the palace and of Kara Tepe lie within a military area and are not accessible.

6 Leriche, P., ‘Decouverte d’une capitale d’empire Kushan’, Archéologia, 417/04.

7 Belenitsky, Civilisation, pp.116–37.

8 Frumkin, CAR XIII, p.245.

9 Rempel, Ornament, p.72; see also above, pp.97, 110, 113.

10 Barthold, Turkestan, p.81.

11 Frumkin, CAR XII, p.176.

12 Belenitsky, Civilisation, pp.140–42.

13 Frumkin, CAR XII, p.173.

14 Frumkin, CAR XII, p.171.

15 Belenitsky, Civilisation, p.46.

16 Belenitsky, Civilisation, p.100.

17 Belenitsky, Civilisation, p.101.

18 Francis, A., ‘Grandeur et misère de Tajikistan et d’Afghanistan’, Archéologia, 387/02.