The site of Tun-Huang lies 14 miles south-east of the village and contains 480 caves. There are wall paintings, statues, painted ceilings and altars from the fourth to the fourteenth century, from the Northern Wei to the Yuan dynasties. One of the inscriptions gives the year AD 366 as the date when these cave temples and shrines were founded. The caves of Tun-huang were known to Europe as early as 1879, when a Hungarian traveller visited them and later described them to Stein.1 Most of the buildings have now crumbled and no decorations from the earliest centuties survive, but in many caves there still stand statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas modelled out of stucco in Graeco-Bactrian or Gandhara style. However, in scenes depicting the lives of monks and in the floral motifs Chinese style predominates.2

The walled-in library was discovered by a Taoist priest in 1900. He was restoring one of the wall paintings when he noticed that underneath the fresco (reality tempera) were bricks not rock. He knocked a hole into the wall and behind it found a room full of scrolls. Seven years later he met Stein, showed him his treasure, and sold him part of it. The following year, when Paul Pelliot met him, there was still enough left for the French scholar to acquire some 15,000 manuscripts.

There were Buddhist religious texts from the fifth century, written in Chinese and in Brahmi; further Tibetan manuscripts; one of the oldest Tibetan chronicles covering the years 650–763; manuscripts written in the Iranian-Soghdian language and Aramaic script;3 old Turkish Manichaean texts and also a Turkish book written in the Orkhon-Yenisei runic script etc. The Buddhist paintings in the caves were described in detail by Stein.4

In Lou-lan, apart from the desiccated corpses, or ‘mummies’, already mentioned, and now in the Museum of Urumchi, the excavations revealed a number of houses built in the same style as those at Niya, but only one stupa, which seems to have been the only religious building there.

The first traveller who noticed some traces of human settlement at Lou-lan, in the eastern part of the Taklamakan, was Sven Hedin at the beginning of the twentieth century. He saw what could have been ruins and excavated some 140 coffins with mummified corpses. More detailed exploration of the site was carried out by the Chinese in 1979, while in 2004, west of Lou-lan, was found a tomb of a young woman; her coffin was wrapped in a buffalo hide, the body was covered with a well-preserved woollen blanket and she had a felt hat and leather boots. Seeds of cereals, also found there, indicated that agriculture was practised here some 2,000 years before the Han dynasty introduced it to China, having been brought from Anatolia. Bronze and jade objects were found in another tomb nearby.5

In Miran a Buddhist temple was found consisting of a cella that was square on the outside and circular on the inside, where there was a stupa. It is possible that the whole was vaulted over. Several other monasteries were founded there in the third and fourth century AD. Many of their shrines were set up in caves, the walls and ceilings of which were covered with paintings. Miran’s art stemmed from India and Gandhara, but was of a subtler character than either of these and attached importance to figural compositions.6 Miran’s style and iconography were then adopted by Tun-huang and numerous other centres in eastern Xinjiang. From the period of Tibetan occupation (eighth and ninth centuries) Stein noticed a Buddhist stupa and scraps of paper and wood inscribed with Tibetan texts. A ruined fort on the same site also yielded a large amount of Tibetan documents.

Niya, further west, is an important site on the river of that name, where in 1901 Stein found wooden tablets and manuscripts in Kharosthi and Sanskrit, as well as seals and figurines with motifs of Greek origin. Stein visited the site again in 1906 and, among other things, found in the ruins of a large building a whole set of Kharosthi records and a cellar with a complete archive.

Beyond a small room which seemed to have served as an antechamber for attendants, there adjoined a large apartment. It was a room twenty-six feet square with a raised platform of plaster running along three of its sides, very much as in the ‘Aiwan’ or hall of any modern Turkistan house of some pretension … a raised roof had been arranged to admit light and air just as in large modern houses.7

The houses at Niya were decorated with frescoes of which some fragments were found. There was a stupa and a temple with a hall where the excavations also yielded fragments of frescoes.

The site of Endere was abandoned already around AD 645. The fort, or citadel, which dates from the time of the Tibetan invasion, was surrounded by a circular wall within which was a temple and a palace. North of the fort a stupa was found built on a square three-tier base on which stood a cylindrical drum.

North-east of Khotan, the site of Dandan-Uilik yielded a number of Chinese documents dating from the years 781–90. (See 48.) Obviously, the Tibetan invasion that marked the end of the Tang domination in the Tarim basin was also the reason for the abandonment of these places. Documents found here were also in Khotanese Saka language, written in the Indian Brahmi alphabet while others were in Sanskrit. The Saka texts were mostly translations from Sanskrit and Tibetan. (See also p.163.)

66 The citadel walls, Balkh

67 Friday Mosque, Herat (detail)

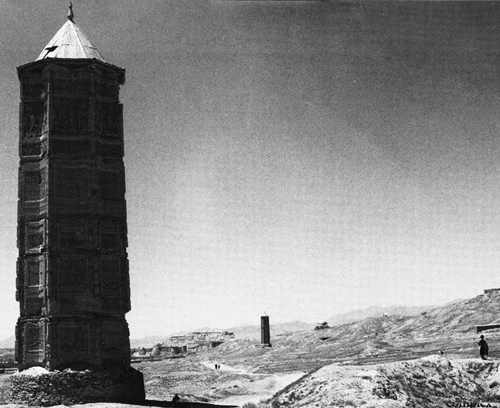

68 Tower of Masud III, Ghazni

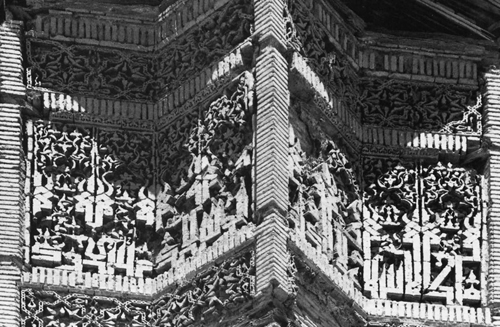

69 Tower of Masud III, Ghazni (detail)

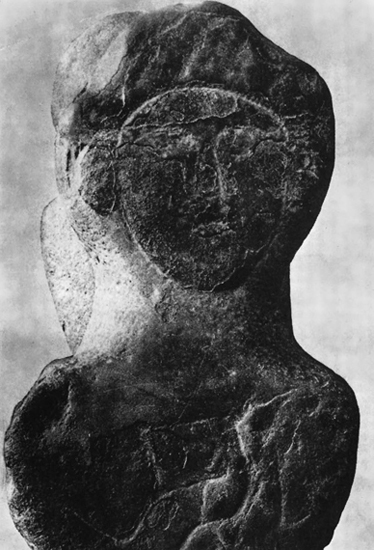

70 Balbal. Turkish gravestone. Tashkent Museum

71 Balbal. Turkish gravestone. Tashkent Museum

72 Parthian art. Ivory rhyton from Nisa

A century after Stein, in 2002, the site of Dandan-Uilik was explored by a Chinese team who found here a temple with a statue of a sitting Buddha in Gandharan style from the seventh century AD, remains of frescoes typical of the kingdom of Khotan, sheep bones, textiles, as well as a coin from the Tang period of China. The site of Domoko, lying on a river flowing parallel with the Keriya, was also explored.8

When the small eighth-century temple was excavated, the external walls were found to have been adorned originally with paintings which included figural scenes. One showed a group of youths riding camels and horses. Some riders are Chinese looking, others Persian and more particularly Sasanian. All have haloes to indicate that they are not only legendary but also holy personages. Dandan-Uilik was abandoned in 791, but in Tang times Chinese influence had made itself particularly strongly felt there.9

The paintings of Dandan-Uilik are among the most important ones found in Xinjiang. Fragments of frescoes, paintings on wood, stucco and clay were also found on the site of Farhad-Beg Yailaki, which was a vast complex containing six temples inside an enclosure with a further one outside it. At Rawak there was a monastery with a huge stupa built on a three-tier base and accessible by four stairways, a feature also found at Taxila, Pakistan. Among the paintings found at Balawaste, east of Khotan, the best known is the Buddha Vairocana, head and upper part of the body with tattooed chest and arms.

Not only was the Khotanese school strongly influenced by China, it was also highly appreciated there, and Chinese artists were in turn influenced by it. It was also greatly esteemed in Tibet. Khotanese artists followed Buddhist monks there, bringing with them styles and traditions that they imposed on the Tibetans. All communities along the Tunhuang trade-route further east were profoundly influenced by the art of Khotan.

The River Keriya, carrying waters from the Kuen-lun mountains, used to flow much further into the Taklamakan desert before it disappeared in the sands. On its lower reaches were a number of settlements, the traces of which were noticed by travellers such as Aurel Stein, Sven Hedin and Paul Pelliot, but excavations began there only very recently, after the Franco-Chinese cooperation agreement was signed.

By 1908 Aurel Stein had already noticed remnants of a building buried in the sand. In the years 1991–94, excavations carried out on the site allowed him to firmly link Karadong as well as the kingdom of Khotan, to the Indo-Gandharian cultural area and, dated approximately to the early thirdrd century BC, to be among the earliest Buddhist settlements in Xinjiang.

Two sanctuaries were unearthed with remnants of statues and paintings. There were large Buddhas and small Buddhas with mandorlas in grey and orange and dressed in robes in corresponding colours. Certain gestures of the hands point to sculptures of Gandhara and Hadda. Historically, these finds provide a missing link between the spreading of Buddhism in China and in Central Asia. Khotan is known to have been an important Buddhist centre at around AD 400, but comparison of Karadong and Miran shows that well before that a certain variety of styles already existed in this area.

Some fifteen sites were found in the protohistoric delta of the Keriya, north-west of Karadong, in an area until then totally unknown, providing evidence of being populated before the Han period, at around 500 BC. Djumbulak Kum was a fortified settlement with massive walls 2–4m high and 4–5m thick, of clay and large pakhsa bricks, built in a different way from the Chinese and showing a Central Asian influence. The inhabitants were sedentary shepherds and farmers with irrigated agriculture as their economic basis. Wheat, millet and barley were grown. Wooden implements and iron utensils were found, too. Mummies found in some thirty tombs were of Caucasian Europoid stock and were buried in a similar way to those found earlier in the south of Xinjiang, at Zhaganluk near Charchan. Mummies found in the Charchan oasis seem to have been of mixed race. Textiles found in these tombs – bits of clothing and decoration – show techniques of spinning and weaving similar to those found in Lou-lan and now deposited in the museum of Urumchi (see earlier) and allow us to reconstruct the dresses and ornaments of the inhabitants. Decorative motives show Iranian influence.10

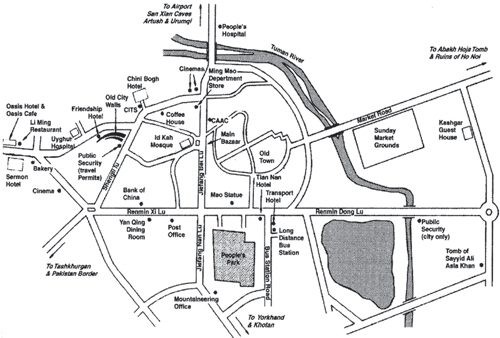

In the city of Kashgar (Kashi in Chinese) the most interesting monument is the mausoleum of Apak Khoja. (See 44 and 46.) It is an important shrine with a number of tombs, built in the late Timurid style in the seventeenth century. The walls are lined with ceramic tiles of rather inferior quality, the dominant colours being green and yellow, with some blue. With its tiled dome and four minarets it is reminiscent of a brightly coloured and not-so-magnificent Taj Mahal.

The mausoleum of Yusuf Kader Khan is the tomb of an eleventh-century sage. It was also built in the Timurid style, and the original date of the building is not known. It is now in full reconstruction with tiles predominantly blue and white. The Great Mosque (Id-Kah) is a nineteenth-century building of limited interest. The mausoleum of Sayid Ali Arslan Khan is a modest structure of unbaked bricks, next to a vast cemetery with many vaulted mazars. (See 45.)

The old town is a maze of little lanes opposite the Id-Kah Mosque. A short stretch of the old city wall, perhaps late medieval, can still be seen not very far from the old British Consulate building.

The main attraction of present-day Kashgar is its huge Sunday market.

North of Kashgar, on the outskirts of the town of Artush, is the mausoleum of the Karakhanid ruler Bugra Khan. Built in the eleventh century, it has undergone several reconstructions and little now remains of its original outlook.

West of Kashgar, the road to the Ferghana valley was first opened in 1935 when the Russian penetration of Xinjiang was on the increase. It was closed again for most of the time after the Second World War and was reopened only recently when the Central Asian republics became independent.

South of Kashgar, on the road to the Pamir, the small town of Tashkurghan (not to be confused with the town of the same name in north Afghanistan) boasts an ancient fort, now in a rather dilapidated state, which is most probably late medieval, but may have more ancient origins. In fact, Ptolemy mentions it as a stop on the road to China.

The road south of Tashkurghan is a modern one leading to the Khunjerab Pass and links with the Karakorum Highway of Pakistan.

The ancient caravan road branched west of it towards the Kilik and Mintaka Passes and from there to Kashmir. Between Kashgar and Tashkurghan two more roads, or rather tracks, branch off to the west, the first one to the former Russian Pamir (which is now Tajikistan’s), the second to the Wakhan valley and into Afghanistan.

Full details of abbreviations and publications are in the Bibliography

1 Professor de Loczy, head of the Hungarian Geological Survey, was a member of Count Szechenyi’s expedition and thus a pioneer of modern geographical exploration in Kansu.

2 Talbot-Rice, Ancient Art, p.219.

3 Stavisky, Bongard, Levin, Abstracts of Papers.

4 Stein, Ancient Tracks, pp.190–207.

5 Hopkirk, P., The Great Game, p.201.

6 Talbot-Rice, Ancient Art, p.214.

7 Stein, Ancient Tracks, p.71.

8 Hopkirk, P., The Great Game, p.80.

9 Talbot-Rice, Ancient Art, p.206.

10 Lebaine-Francfort, C., ‘Les Oasis retrouvées de Keriya’, Archéologia, 375/01.