Although a very ancient city, Kabul was overshadowed in the earliest part of its history by Kapisa (Begram), which was the capital and the royal residence at the time of Greek Bactria as well as of the Kushan Empire. Kapisa remained the centre of the area under the Sasanians and the Hephthalites. Suen-Tsang, the Chinese pilgrim of the seventh century AD, barely mentions Kabul, but describes Kapisa at length and with enthusiasm. Kabul began to play a more important role at the time of the Arab conquest, when the victorious advance of Islam was halted by the stubborn resistance of its rulers, the Turkish, Indianised dynasty of the Kabulshahs or Ratbilshahs, also referred to as the Turk-Shahi. Although Kabul was taken in 644, the Arab occupation did not last long, and the Turk-Shahis survived for another 200 years, until, around 850, they were replaced by the purely Indian Hindushahis. The definitive victory of Islam came only with the Ghaznavids, who captured Kabul in 977.

In the time of the Timurids, Kabul was a provincial capital, but the real turning point came when Babur, the young Timurid prince of Ferghana, made it his capital in 1504. It was from here that he departed in 1525 for his celebrated conquest of India, but even after he established his imperial residence in Agra, he kept returning to Kabul. He also wished to be buried in the beautiful gardens that he founded. However, unrest following his death in 1530 prevented the immediate fulfilment of this wish, and it was onlt nine years later that his wife brought his remains to Kabul.

Bagh-i Babur Shah, Babur’s Garden, is the first of the famous Moghul gardens of which a number were built by Babur and his successors in Delhi, Lahore and Srinagar. It follows the traditional Persian principle of the Chahar-Bagh, or Four Gardens, which is a square divided into quarters by channels of running water. The garden consisted of several such squares laid on sloping terraces. In the centre of one of them usually stood a pavilion.

The Bala Hissar, or the citadel, stands on a rocky spur where a fortress is known to have stood already in the seventh century. The walls of Kabul, 18ft high, and almost 12ft thick, which the Hephthalites are said to have built originally, start here. It was in this citadel that Babur was married and his son and successor Humayun was born. In Moghul times, gardens and palaces were built within the citadel, which probably resembled the forts of Lahore, Delhi or Agra. It became a royal residence again at the end of the eighteenth century under Timur Shah. In the early nineteenth century there was a Lower Fortress with three palaces and, at the top of the hill, the Upper, or Inner, Fortress with the armoury and the prison. The British army was quartered in part of the citadel for a short time in 1839. It was then sporadically occupied by the ruling amirs until the 1870s. In 1879, it was damaged by an explosion of the powder magazine, and in 1880 it was finally demolished by the orders of General Roberts, in retaliation for the massacre of the British mission the previous year.

The Christian cemetery contains the tomb of Sir Aurel Stein, the explorer and archaeologist who died here in 1943 at the age of 82.

Near the village of Begram, some 40 miles north-east of Kabul, at the confluence of the Panjshir and Ghorband Rivers, lies a long mound encircled by high ruined ramparts. This was Kapisa, the summer capital of the Kushan kings. It was excavated twice, in the late 1930s and the early 1940s. The stratigraphic sequence established by Ghirshman in 1941–42 shows three major occupation periods. The first was from the second century BC to the second century AD, which coincides with the Indo-Parthian level of Taxila. This was perhaps the capital of the last Indo-Greek (Graeco-Buddhist) kingdom. The second was from the second to third century AD, a Kushan city probably destroyed by the Sasanian King Shapur in 241. The third was from the third to fifth century AD, a period up to the Hephthalite invasion. This invasion was, of course, not the end of Kapisa, for Suen-Tsang, when he visited it in the seventh century, found it a very lively place, although a little rough.

The Kingdom of Kia-pi-che has a circumference of about four thousand li. In the north, it leans on the snowy mountains; on the other three sides it is surrounded by black mountains. The distance around the capital is about ten li. The country is well suited for the cultivation of cereals and wheat; there is a great number of fruit trees… The climate is cold and windy. The character of the inhabitants is cruel and rude. Their language is low and coarse and their marriage is just a shameful mixing of sexes… The inhabitants wear dresses of wool, sometimes lined with fur. In trade they use gold and silver coins and small bits of copper the size and shape of which is different than in other kingdoms. Their king … rules over a dozen kingdoms. He loves and protects his people; he respects and honours the Three Jewels. Every year he has a silver statue of Buddha made, eighteen feet high and then he calls the Grand Assembly in which he dispenses grants to the needy and alms to the widowed men and women… There are a good hundred monasteries there with more than six thousand monks who all study the doctrine of the Greater Vehicle (Mahayana)… There are several dozen temples of various deities and a thousand heretics. Some of them go naked, others rub themselves with ashes or make bonnets of skull-bones and wear them on their heads… The princes of various kingdoms in India return in summer to Kia-pi-che; in spring and in autumn they stay in the kingdom of Kien-to-lo (Gandhara). This is why, in each place where these hostages stay for three seasons, there was a monastery built for them. This one, which we describe, has been built as their summer residence. This is why, on all the walls, they have painted the portraits of these hostages whose faces and dress resemble those of the men from the East [sc from China]1

The excavations of Hackin (1936–40) yielded some of the most spectacular museum pieces found in this century. In the so-called new royal city two rooms were found that were probably a rich merchant’s treasure or warehouse. They were filled with luxury goods and rare Buddhist objects, carved ivories from India, vases and lacquerware from China, classical Graeco-Roman bas-reliefs, Graeco-Egyptian bronzes, Phoenician glassware. There was jewellery from India, Rome, Egypt and Central Asia. Some specimens even resembled those found in Sarmatian tombs in the Russian steppe.

Two Buddhist monasteries were excavated to the east of the site of Begram, dating probably from the first to third century AD. One of them, Shotorak (Baby Camel), was the monastery built for the Chinese hostages taken by the Kushans.

The most romantic of these dead monasteries is the Shahzade-I Chin, ‘The Chinese Princes’. It is, in fact, the place where a clutch of distinguished Chinese hostages was held, in honourable confinement, by the Kushan emperor Kanishka. The emperor is said to have paid his prisoners the compliment of sharing their monastery prison with them for a month.2

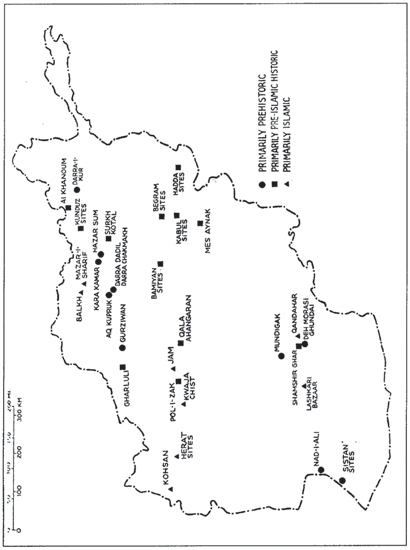

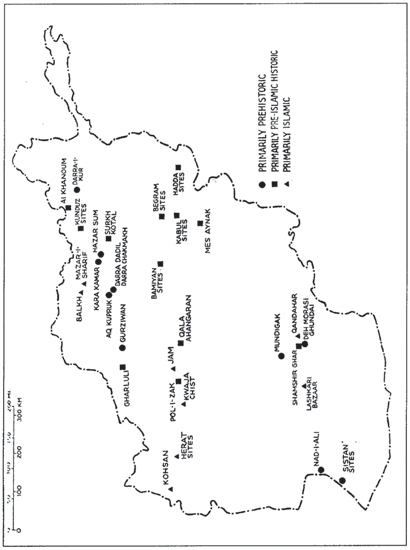

Fig. 29 Archaeological sites in Afghanistan

These were the ‘men from the East’ whose portraits on the walls Suen-Tsang saw some five centuries later. It was a large complex consisting of two spacious courtyards and ten stupas bearing bas-reliefs in schist depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha. The main stupa in the first courtyard measured 27 square feet and was built of stone, whereas the surrounding buildings were built of clay. Inside the stupa was found a terracotta vase filled with earth. No other relics were found, and it is assumed that the earth probably came from some holy spot connected with the life of Buddha, and was itself a relic.

There were four small stupas in front of the main one, some 4.5 square feet. None had a cupola. All show certain similarities with the stupas at Mohra Moradu, Jaulian and Takht-i Bhai in north Pakistan. The sangharama or monastery, was a two, or possibly three-storey building. Its ceilings were probably made of matting covered with clay and supported by wooden columns. Everywhere, the dome, or cupola, is conspicuous by its absence.

The style of the bas-reliefs belongs to the latest period of Gandharan art, but the reliefs are heavier, more rigid and more schematic. Among other sculptures the most remarkable find was a throne supported by two lions. The other site, Paitava, is a stupa dating from the third or fourth century AD with some stucco heads and bas-reliefs in schist.

The Guldara stupa, in desolate countryside about 3 miles from the village of the same name, stands on a square platform on a high rocky spur. Below, in a sheltered corner, a spring with a single tree catches the eye, the only refreshing sight in the stony desert. (See 36.) The stupa has a square base, a two-tier drum and a dome. The dome has collapsed and only part of it is still in position. The square base is an unusual feature, as most Buddhist stupas in Afghanistan have only a high cylindrical drum. The base is decorated on three sides with a row of false columns and a central niche; on the south-west side, a staircase leads to the platform on top of the base. The decoration on the lower part of the drum is fairly simple, but the upper part shows elaborate ornamental ledges, which form a false arcade of alternating half-circles and half-hexagons. In between is a motif symbolising the umbrella mast. According to some authorities,3 this motif is that of a console carrying ornamental stucco eagles with spread wings, painted gold. The masonry, both on the base and on the drum is of the ‘diaper’ kind, typical of the Kushan period. The layers of schist that make the wall-facing are interspersed with large blocks of stone of a different colour, thus achieving a pronounced ornamental effect. Gold Kushan coins and several other gold objects were found in the reliquary chamber inside the drum. The stupa was part of a monastery complex, the main building of which was excavated in 1963–64.

East of Kabul, the most important site is Hadda. It is the modern name of a group of Buddhist monasteries, stupas and caravanserais situated on the outskirts of the ancient city of Nagarahara, which corresponds to the present-day Jalalabad. The site is some 5 miles south of Jalalabad on what used to be one of the main caravan roads linking the Punjab and the Kabul area. It dates from the second to seventh century AD, when the Jalalabad area was among the most sacred in the Buddhist world. There were reputedly as many as 1,000 stupas in the land of Hilo, which is how the Chinese chroniclers referred to Hadda. So far, the French archaeological mission has explored more than 500 of them.

There are seven main groups of ruins in the area; the most important of them is the site of Tepe Kalan, on which the excavations concentrated. They have yielded a fantastic number of statues in limestone, schist and stucco that show great similarity with the art of Gandhara and Taxila, although with a slightly provincial touch. Between 1923 and 1928, the French expeditions uncovered some 23,000 heads of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, various demons and other figures, such as donators, monks etc. Apart from the heads there were bas-reliefs and other sculptures depicting episodes from the Buddhist legends, scenes of offerings and individual persons. Some fragments of secular scenes were also found in addition to pieces of architectural decor. The art of Hadda comes from two main periods: the second to third century AD and the fifth century. It is a mixture of Bactrian, Graeco-Roman and Indian elements. The Western influence is particularly visible in the classic profiles, pseudo-Corinthian capitals, vine-scrolls and Roman drapery.

It was in Hadda that the stucco technique reached its peak. The bodies of figures were moulded in mud and covered with decorated gypsum plaster. The heads were made separately from lime plaster mixed with straw and pebbles, and then covered with a shell of stucco, which consisted of lime, sand and marble dust. They were painted in brigh colours, pink and ochre, the hair often blue.4

The valley of Bamiyan, 146 miles north of Kabul, with its colossal statues and innumerable caves, has attracted the interest of travellers ever since the Buddhist pilgrims Fa-Sien and Suen-Tsang described it in the fifth and seventh centuries AD respectively.

The valley, which is some 9 miles long and not more than 2 miles wide lies at an altitude of 8,250ft, but it is well sheltered from winds and has abundant water supplies. (See 64.) It is now as it was in the past, an oasis of intensive cultivation and refreshing greenery amidst the barren mountainous landscape that surrounds it on all sides. It became the home of a colony of Buddhist monks in the early stage of their movement across the Hindu Kush and into northern Afghanistan. It was conveniently situated halfway between the important cities of Balkh and Kapisa, on the caravan route linking India with Bactria and Transoxania, at a place that, probably for centuries before, had been a natural caravan halt offering a sheltered resting place to traders and pilgrims, well equipped with provisions and repair facilities, grazing grounds and replacement mounts. Its additional attraction, which may well have been decisive for its selection as a place of worship, was a long, sheer vertical cliff-face of soft rock, eminently suitable for digging cave sanctuaries and carving statues. There was an established tradition of such sanctuaries in India, whence Buddhism came, and no doubt Ellora, Ajanta and others provided the models for the first cave sanctuaries at Bamiyan, just as they were to provide them for the similarly situated sites later developed in Xinjiang.

The most striking feature of Bamiyan were the two giant statues of the Buddha, carved in the cliff, one 115ft and the other 175ft high. Each was surrounded by a number of man-made caves of various sizes and shapes, some of them in elaborate sanctuary complexes. Between them there were other statues of seated Buddhas.

To the west of the statues was the capital city, its northern flank protected by the cliff. Nothing remains of that city, except perhaps some disused caves. A mound east of the ‘small’ Buddha, which hides the remnants of a stupa, is the only trace of an open-air construction from the Kushan period. The complex of caves surrounding the statue of the smaller Buddha originated as an extension of the monastery into the rock.

The caves were not spread haphazardly over the rock face. They formed organised units serving definite purposes, and they were connected by a wealth of communications, both horizontal and vertical. Steps and staircases were dug in the rock and horizontal galleries linked caves on the same level so that each complex had its own independent access. Unfortunately, many of these communications have been destroyed or blocked, and it is not easy nowadays to reconstruct the original picture. (For the present state of the site, see p.213.)

The niches of the statues and several of the caves were decorated with frescoes of which a fair amount is still discernible. Their style is predominantly Indian with some Iranian elements.

The smaller of the two Bamiyan statues of the Buddha stood in the eastern part of the cliff in a niche 26ft deep. Its disproportionately large head, wide shoulders and thick-set body betray an artistic primitivism as well as inexperienced craftsmanship. The hair is dressed in Greek fashion, the folds of the garment are stiff and unnatural. The face has been systematically obliterated. The whole statue has been hewn out of solid rock, with the exception of the folds and the forearms, which were made of plaster. The forearms were missing. The statue was covered with a layer of clay mixed with straw on top of which came a layer of mortar, which was painted. The body was originally blue, the hands and the face were painted gold. The niche was decorated on the inside with frescoes, some of which are still clearly visible. They formed a vast composition centred around a lunar, or solar, deity, surrounded on the right and on the left by two rows of figures, bodhisattvas, donators etc. There are strong indications that the frescoes, which resemble those found at Kyzyl and Kumtura in Xinjiang, are of Iranian origin and were probably executed in the fifth or sixth century AD.

Artistically, the statue of the ‘large’ Buddha, which stood a quarter of a mile further west inside a trilobate niche, represents a considerable improvement. Its proportions were better balanced and it looks as if the artists modelled their work on certain Hellenistic statues. (See 61.) On the other hand the ornamental folds of the garment were very shallow, and in places barely indicated, being thus closer to the schematic arrangement typical of the Gupta period, which differs considerably from the softer and deeper folds of the Hellenistic style. The face, again, has been completely destroyed; only part of the chin remains. The forearms, which were missing, were not cut out of the rock but were made of plaster carried on wooden beams. The legs were damaged by cannon balls fired by Nadir Shah’s troops. The folds were modelled in plaster and fixed to the body by wooden pegs, the holes of which are clearly visible.

The body was probably painted red, while the face and the hands might again have been gold. Being later than its smaller counterpart, it must be assumed to have originated in the fifth or sixth century AD.

The niche of this statue was also decorated with frescoes, the oldest of which can be seen on the lateral surfaces. There is, for example, a series of five medallions with two female and one male figure in each, surrounded by winged demons reminiscent of Gandharan iconography, a series of five Buddhas resembling those of Ajanta – although drawn much more clumsily – seated under the sacred fig tree with a group of royal donators, framed by architectural decoration and floral ornaments. There are female figures with Indian faces, semi-nude or thinly veiled in transparent robes, some dancing and others playing musical instruments. Behind each group can be seen a dome or an umbrella of a stupa. The contours of the figures were drawn in ochre, and indigo-blue was used for some surfaces, which, again, points to the Indian origin and, in particular, to the Gupta period. Certain details of dress and hairstyle, as well as some decorative elements, show Iranian influence, while the virtuoso brush stroke and the softness of lines betray a Chinese hand.5

In the valley of Kakrak, a short distance to the south-east of the main valley, another giant statue of the Buddha stands 23ft high with its face intact in a niche amidst a group of cave sanctuaries. The niche was decorated with frescoes and sculptured ornaments.

Two other sites in the valley of Bamiyan must be mentioned. East of the township, the spectacular ruins on a high rocky promontory is the Shahr-i Zohak, the Town of Zohak, also called the Red City because the colour of its brick wall is reddish-brown. (See 38 and colour plate 17.) Zohak, or Zahak, was in Iran’s national epic, the Shahname, a tyrant reigning 1,000 years, in another epic a legitimate king. The rulers of Ghor traced their ancestry to this legendary figure. According to Schlumberger, the fortress was originally a Turkish castle dating from the sixth or seventh century AD. The ruins of the fortress are one of the most dramatic sights in the whole country. Soaring on inaccessible cliffs, perfectly blended with the narural rock, dominating the fertile valleys to the east, north and west with its three-tier ramparts, it was nevertheless conquered and destroyed by the Mongols of Chingiz-Khan. The same destiny befell the strongly fortified Islamic city of Bamiyan, the ruins of which are now known as the Shahr-i Gholghola, the City of Murmurs (more exactly, City of Noise). It was built in the eleventh century on a hillock south of the Bamiyan cliff, in the middle of a well-irrigated plain. The patterns of the bazaar, the mosque, the palaces and the caravanserais of this once prosperous city are still discernible in the maze of dilapidated clay walls. From the top a beautiful view extends towards the valley of Bamiyan in the north, the valley of Foladi in the south-west, the Kakrak valley due south and the majestic barrier of the Kuh-i Baba on the horizon behind it.

Almost exactly halfway between Kabul and Bamiyan, about 31 miles from the town of Charikar and 3 miles from the village of Siyahgerd, lies the site of Fundukistan, one of the most important monastic sites in the country. Excavations carried out in 1937 revealed a monastery complex consisting of a square courtyard surrounded by a wall with twelve niches, and with a small stupa in the centre. The architectural decoration, arcades with foliated scrolls and columns with pseudo-Corinthian capitals is perhaps less remarkable than the magnificent frescoes reflecting both Indian and Sasanian elements, and the sculptures reminiscent of the Indian Gupta school.6

Kunjakai, some 25km west of Kabul, on the ancient road to Gbazni, consists of a stupa, a monastery and niches between the two, dominated by a citadel on the hill opposite. It has been looted since the ninth century: sculptures that were in the niches have now mostly disappeared and the stupa decoration has also been destroyed, probably by the Muslims, (first by the invasion of Yakublais Saffar at the end of the ninth century, and then by Mahmud of Ghazni a century later). It was similar to the stupa of Guldara (see p.185), and was just a little smaller than the stupa of Tepe Maranjan (see p.189). Its side measured 16.8m, the height was 6.4m. Either side of Kunjakai were found two cemeteries and three archaeological sites, so far unexplored.7

Khwaja Safa south of Kabul, near the Bala Hisar, mentioned for the first time by Charles Masson in 1830, was also a monastery with a stupa and a wall with niches, the sculptures of which have disappeared. In its lower part were several chapels, some of which contained remnants of statues painted red and ochre and gilded.8

Tepe Naranj, south of the citadel of Kabul, is a site dating from the fifth to sixth century, and was first excavated in 2004. It yielded some pre-Islamic pottery, bricks from the Hephthalite period and fragments of statues of bodhisattvas in Gandharan style. A major discovery was a statue of a sitting Buddha, with a bodhisattva Vajrapani in a style characteristic of the Hephthalite period on his right. A circular meeting room, covered with a layer of ashes, is so far a unique architectural feature. Excavations in 2008 have uncovered traces of a small monastery below the site and another approximately 2km south-east, which seem to confirm an artistic style called by some scholars ‘Hephthalo-Buddhist’.

In 2005, traces of a monastery were found in the Babur Gardens in Kabul, linked with the monasteries of Tepe Maranjan, Khair Khane and Tepe Khazana.9

Mes Aynak is a major site, some 30km south of Kabul, at an altitude of 2,500m, in immediate proximity of a giant copper mine owned by the Chinese, which threatens to destroy it in the near future. There were three monasteries and at least two large stupas. Shards of pottery found here indicate that the site was occupied from the third century BC until the fifteenth. So far, one of the monasteries, near the village of Gul Ahmad, occupied probably until the end of the tenth century, has been explored. Two chapels and some monastic cells were uncovered, next to which were found eight large jars buried in the ground that probably served as water reservoirs. A small square stupa had on one side three lions painted red, of which only the front paws can be discerned. A clay statue of a sitting Buddha was also painted in red ochre. Generally, the style of these sculptures, technically more primitive than the sophisticated ‘Hephthalo-Buddhist’ style at Tepe Naranj, points to the last period of occupation of the site. Most of the paintings and sculptures have disappeared, probably because of a military attack, when the monks tried to protect the site by blocking it with bricks and clay. Ancient copper smelting took place here, as blackened areas of the ground indicate. Some 150 statues have been found.10

Recent excavations 2010–11 have centered on the second monastery, called Tepe Kafiriat. At the time of writing only about half of the building has been uncovered. Its base was a large rectangular platform with round turrets in each corner; there were monastic cells in the north-western part and a group of stupas in the south-east. Access was probably through a monumental entrance in the south-east, which has not been found so far. There was a large stupa surrounded by eight small ones; a huge statue of a sitting Buddha next to it was made of clay and painted and around it were small sculptures, also of clay. An unusual item was a statue of a sitting bodhisattva accompanied by a monk, both in schist, which is a material rarely used in this area. On the north side was a large central courtyard surrounded by small cells roofed with cupolas based on squinches, which is also a rare element. The building was obviously rebuilt several times. Two chapels were added on either side of the entrance. In one of them was found a statue of a lying Buddha some 3m long, as well as traces of other monumental statues of which only the feet can be seen. In the second chapel there were statues dating from at least two different periods. From the first one there is a sitting Buddha covered with gold leaf, from the second, much later and dating probably from the sixth to eighth centuries, there are monumental statues of six bodhisattvas and one Buddha.

A few miles further away, near the village of Baba Wali, remnants of a fortified settlement, which probably guarded the ancient mines, can be seen. In 2010, fragments of some manuscripts in brahmi were found here, dating from the fifth century, as well as stone sculpture with traces of paint, representing the Buddha Dipankara, dating probably from the second to the third century AD. Other buildings, stupas and monasteries are still waiting to be explored.11

It seems that the site of Mes Aynak was one of a long string of settlements along the road by which Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia and to China.12

Ashoka (c.270–32) had edicts carved in rocks throughout his empire. These were primarily concerned with defining the order of his state and ensuring its unity by promoting Buddhism, wich was seen as the principal instrument in achieving this aim. A number of pillars inscribed with religious exhortations and legal and administrative orders were erected in various parts of the empire. The languages used in them reflect relations with Persia and the Hellenistic West.

A rock edict of Emperor Ashoka was found near Chehel Sina in 1958. It is a stone slab 55 x 50cm, with fourteen lines of text in Greek and eight lines in Aramaic, which until the finds of Surkh Kotal and Ay Khanum was the easternmost Greek inscription, and also the only one attributed to Ashoka. Another fragment of a Greek inscription came to light in the Kandahar bazaar in 1963, which contained twenty-two lines on a limestone block measuring 45 x 70cm, and can also be attributed to Ashoka. It comes, presumably, from Shahr-i Kuhna, the Old City of Kandahar. In the same year, an inscription in Prakrit and Aramaic was also found in the bazaar. It had seven lines of script on a 24 x 19cm block. A further four Ashoka inscriptions were found in the Laghman area in 1969; three of them were in Prakrit, or another Indian language, and one in Aramaic.

This hoard, dating from the Bronze Age, was found in 1966 in the province of Badakhshan. It consisted of five gold and twelve silver vessels from different periods and different localities. The motifs and the techniques used were a mixture of Indian, Iranian, Central Asian and Mesopotamian elements. On this evidence it seems probable that most objects could be dated to c.2500 BC.

Full details of abbreviations and publications are in the Bibliography

1 Translated from Julien, S., Hiuan-Tsang, pp.40–42.

2 Toynbee, A., Between Oxus and Jumna, p.128.

3 Auboyer, J., Afghanistan et son art.

4 Barthoux, J., ‘Les fouilles de Hadda’, Mem. DAFA IV; 1933.

5 Godard, A., Godard, J., Hackin, J., ‘Les antiquites bouddhiques de Bamiyan’, Mem. DAFA II, 1928.

6 Duprée, N., Duprée, L., Motamedi, A.A., The National Museum of Afghanistan, p.99.

7 Paiman, Z., ‘Kaboul, les Buddhas colorés des monasteres’, Archéologia 473/10.

8 Paiman, Z., ‘Kaboul, foyer d’art bouddhique’, Archéologia 461/08.

9 Paiman, Z., ‘Region de Kaboul, nouveaux monuments bouddhiques’, Archéologia 430/06.

10 Paiman, Z., ‘Afghanistan, decouvertes a Kaboul’, Archéologia 419/05.

11 Buddha Dipankara, one of the Buddhas of the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana) was a protector of travellers and traders.

12 Fournie, E., ‘Mes Aynak, joyau bouddhique de l’Afghanistan’, Religions et Histoire 37/2011.