The oasis of Herat stretches along the right bank of the Hari Rud, between the river and the foothills of the Safid Kuh range, the ancient Paropamisus, in the north. On the left bank, the green belt is confined to the immediate vicinity of the riverbed. The stony and sandy desert begins, abruptly, only a few hundred yards from the river. From the air, it can clearly be seen that the irrigation network extended much further in the past and that the area of cultivated farmland began much higher upstream than now.

Herat is, without doubt, one of the oldest cities on Afghan soil. When Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered it in the sixth century BC, it was already an important stronghold mentioned in the Avesta as Hairava. Alexander took it in 330 BC, rebuilt and strengthened the fort, and gave it the name of Alexandria Ariana. It was held in succession by the Seleucids, Parthians, Kushans and Sasanians. For a period in the fifth and sixth centuries it was dominated by the Hephthalites, or White Huns, who ruled their empire from the nearby province of Badghiz. At the end of the sixth century it was sacked by the Turks, and in 645 it fell to the Arabs. From then on, it remained firmly Muslim, but the story of conquest continued. It was taken by Mahmud of Ghazna in the year 1000, fell to the Seljuks after the defeat of the Ghaznavids in 1040, and to the Ghorids in 1175. Although the Ghorid domination lasted less than half a century, it is the earliest period from which some architectural monuments have been preserved in Herat.

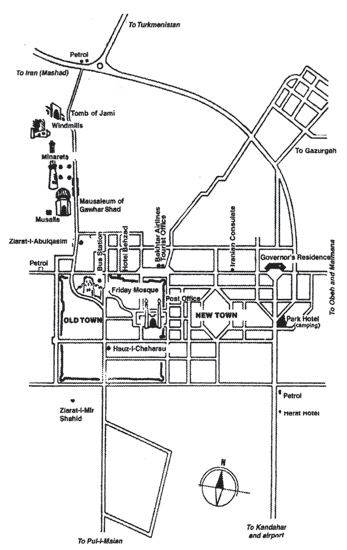

Shortly before the Mongol invasion, Yakut considered Herat to be ‘the richest and largest city he had ever seen’.1 His contemporary, Kazwini, notes that ‘here might be seen many mills turned by wind, not by water’, for him an uncommon sight.2 Some of these curious mills, working on the principle of a vertical shaft revolving in a cylindrical tower, still exist.

The second period of prosperity came in the fifteenth century, under the Timurids, Shahrukh (1405–47) and Husayn Baykara (1469–1506). Shahrukh, Timur’s fourth and youngest son became governor of Herat after his father’s conquest of the city. When, after a brief interlude following Timur’s death in 1405, he established himself as his successor, he made Herat the capital of the Timurid empire. Politically, culturally and commercially, it became the metropolis of Central Asia, competing with and, for a time, surpassing Samarkand.

The citadel (Arg, Bala Hissar) is an imposing building constructed in the ninth or tenth century on the site of an earlier fortress, the origins of which would probably go back to antiquity. (See 5.) No excavations have been carried out here, and the hypothesis that this may be the site of Alexander’s fort, Alexandria Ariana, still awaits confirmation. The ramparts and round towers were rebuilt several times, especially by the Kart dynasty after the Mongol onslaught, and by Shahrukh in the wake of Timur’s conquest. It forms a rectangle of approximately 4,300ft by 4,600ft, situated on an artificial mound in the north-western corner of the city. A bastion built by Shahrukh between the northern city wall and the north-eastern side of the fortress made the city and the citadel into a single defensive complex. The ramparts of the fortress were equipped with semicircular towers; on the bottom part of one of these in the north-western part, remains of an inscription frieze with geometrical patterns in glazed bricks could still be seen. This decorative frieze consisted of a wide ornamental band framed in a curious way with dark and pale-blue tiles and filled in with a sophisticated imitation of Arabic calligraphy in pale blue.

Although after the citadel the Friday mosque was the oldest monumental building in Herat, medieval texts contain surprisingly little information about it. As we have seen in Ibn Hawkal, it stood in the midst of the chief market, and no mosque in all Khorassan or Sistan was its equal in beauty. (See 62 and 67.) Other sources are even more laconic. We would have to wait until the nineteenth century for a more meaningful description, and by then, of course, the original aspect of the building might have been altered beyond recognition. To Byron,

… this morose old mosque inside the walls growls a hoary accompaniment to the Timurid pageant of the suburbs… The Friday mosque was old and ruined before the Timurids were heard of. It is less ruined now they are not heard of. For seven centuries the people of Herat have prayed in it. They still do so, and its history is their history.3

The layout of the building is that of a traditional Iranian four-iwan mosque, which developed from a combination of the original Arab hypostyle mosque and an Iranian fire temple.4 On the west side – or the south-west, according to some sources – of a courtyard measuring approximately 300ft by 195ft is the main iwan with a prayer hall, flanked by two minarets. Opposite is the entrance iwan, and in the middle of the longer sides of the rectangle, two lateral iwans. All the iwans are unusually deep. Inside the arcaded wings enclosing the courtyard are halls of columns concealed behind the façade niches. Each of the courtyard iwans has its counterpart in the outer façade. All outer iwans are flanked by two minarets each, and there is a small turret in each corner. The present state of the building is the result of restoration carried out since the mid–1940s.

The general impression may be Timurid, and there are undoubted similarities with other monuments of the same period, but conspicuous differences point to earlier origins. For example, the pillars in the passages are remarkably strong, the iwan vaults have unusual proportions, and the points of the arches differ from the usual Timurid style. Melikian-Chirvani,5 who has analysed the building, believed these elements to be closer to twelfth- or thirteenth-century models. There are at least three distinct items pointing to this period of origin: right and left of the western iwan, the low vaulting and its brick pattern, in addition to the inscription along the base of the vault in the passage leading south from the iwan; a large portal on the south side of the eastern façade, half hidden under a layer of late Timurid decoration; and the remnants, still visible some forty years ago, of a mausoleum incorporated into the northern façade just behind the northern iwan.

The portal in the eastern façade was ‘discovered’ only in 1964, although Byron noticed ‘a Kufic legend in fancy brick over an arch in the north-east corner’,6 and Wilber described it – with a photograph – in 1937.7 Earlier stucco decoration has been found under Timurid tilework. The portal, which originally had a high arch lined with with an inscription frieze, was framed by a band of script and flanked with two pillars covered with geometrical ornaments. The medallions decorating the spandrels of the arch and the patterns of the columns were executed in incised terracotta. The Kufic in the portal, likewise in incised terracotta, was more conservative in design than that in the passage, but also of a very high quality. The motifs in the frame are essentially the same as those on the minaret in Dawlatabad,8 which again dates from the twelfth century.

Thus three separate sections of the mosque, lying west, east and north of the courtyard, date back to the early thirteenth century, to the reign of the successor to Ghiyat-ud-Din, Abu’l-Fath Muhammad ben Sam, or of his son. It can therefore be assumed that the layout of the Ghorid mosque was substantially the same as it is now and that all the subsequent restorations have little affected the inner structure. Only the eastern and western façades show sixteenth-century additions. The outer façades were, of course, completely reshaped. A beautifully decorated bronze cauldron stood until recently in front of the eastern iwan.

Walking north from the citadel past the recently restored fifteenth-century mausoleum of Abu’l-Kasim on the right, we arrive at a vast site stretching, on the left of the road, along both sides of an irrigation canal and marked by a number of high elegant minarets that look rather like a group of factory chimneys from a distance. There are six of these at present: four in the middle of an enormous field of rubble on the north side of the canal, the remaining two in the gardens on the south side of it. A beautiful mausoleum with a typical Timurid ribbed dome stands between the two. This is all that remains of what the French traveller, Ferrier, described in 1845 as ‘one of the most accomplished, most imposing and most elegant architectural complexes in Asia’. It is the site of the Musalla, which, in the fifteenth century, was a vast complex of learning, a ‘university district’, founded by Queen Gawhar Shad, the wife of Shahrukh, in 1417 and extended and completed by Husayn Baykara at the end of the century. (See 55.) Musalla means ‘space (or place) for prayer’. In Arabic, the word originally indicated an open space oriented towards Mecca, the same as the Persian word ‘namazgah’. Later, it was used in a wider sense to describe any place destined for religious gatherings.

There is a sketch made by a British officer just before the demolition of 1885. It shows the portal of the madrasa in an advanced state of decay, with one minaret out of the two, on the right, the arcades of the madrasa court, and behind, the iwan and the two domes of the Musalla. It was on this sketch that Byron9 based his description, in which the Musalla had a monumental portal, a square courtyard with two-storey arcades, and four minarets. Opposite the portal, on the west side, was a single iwan, behind which were two circular chambers with saucer-shaped domes. Adjacent to the north side of the Musalla was the madrasa, inside which stood the royal mausoleum.

Turning now to the description of the existing buildings: the minaret with one gallery stood in the western corner of the courtyard of the Musalla, which according to a reconstruction measured some 386ft by 231ft. Its octagonal base was once covered with exquisitely carved marble panels. The whole tower was entirely covered with ornaments in mosaic faience and bands of calligraphy, of which only parts remain.

The other minaret, with two galleries, standing to the east of the mausoleum was probably one of the flanking towers of the entrance iwan of the madrasa. The galleries were supported by lavishly decorated stalactite vaults (mukarnas). On the tower itself, brick ornaments alternated with bands of tilework. Both minarets have lost their tops.

The four minarets on the north side of the canal form a square of some 330ft, which was the area occupied by the madrasa of Husayn Baykara. The minarets are between 100ft and 130ft high, but their original height cannot be assessed as their tops, too, have collapsed. Their decoration consisted mainly of geometrical ornaments in mosaic faience, turquoise blue framed with white. Curiously enough, the white mosaic has survived better than the turquoise one, so that in parts bare bricks are laced with a pattern of white tiles.

The mausoleum, commonly ascribed to Gawhar Shad, stands in a pine grove not far from the canal. It is a squat square structure with a bulbous dome on a high drum, some 83ft high. It has been almost entirely restored, and remnants of the original decoration can be found on the west side only. (See colour plate 21.) The drum has also been partly restored, but a good deal of the decoration still exists. The dome, on the contrary, is in its original state, with a dilapidated top but with the lower part of the rib decoration still in place. (A damaged part of the top shown in a photograph in Byron has been repaired). The drum bears a high outer dome and itself exceeds the height of the lower, inner dome.

On the outside, the decoration of the dome consists, on the ribs, of geometrical ornaments in turquoise, blue and white tiles. At the bottom is a white and blue band with medallions of rosettes and stylised lettering. The transition between the dome and the drum is made by stalactites, again decorated in blue and white. The upper part of the drum carries a band of rectangular medallions filled with floral ornaments, white on a blue background. In the middle part is an inscription frieze, now largely damaged, whereas the lower part consists again of ornamental rectangles, only much larger than at the top. Dark blue hexagons with stylised golden flowers are separated by natural brickwork with blue and white rectangles above and below.10

Inside, there are two zones of transition between the square base and the dome. First, four pointed squinches make the square into an octagon, and then a band of sixteen mukarnas-niches transform it into a sixteen-sided figure on which rests the dome. The dome and the transition zones offer one of the most spectacular decorations ever achieved in Islamic architecture. Intersecting pointed arches – which are remotely reminiscent of the gothic arch, but have nothing common with it,11 divide the sphere into various polygons and mukarnas decorated half- and quarter-domes bearing painted ornaments in lapis blue, gold, ochre and white. The lapis-blue pigment was obtained from the genuine lapis lazuli of Badakhshan.

It is not clear how many tombs were originally in the mausoleum. Some sources mention as many as twenty. Khanikov still saw nine in the 1860s. Yate saw five and Byron only three. There is nothing unusual in this, as the habit of re-using tombstones was widespread. Strangely enough, where Byron saw three, there are now six. According to Wolfe,12 they belong to Gawhar Shad (d.1457), her son Baisanghur (d.1432 or 1433), his son Ala-ad-daula (d.1459), his grandson Ibrahim (also d.1459) and two other members of the family, Ahmad and Shahrukh ibn Sultan Abu Said (d.1493). As mentioned above, the mausoleum was originally built for Prince Baisanghur, who predeceased his mother; Golombek (and also Saljuqi, Khiaban) call it the mausoleum of Baisanghur and Gawhar Shad.13

Some 3 miles north-east from the city, and near the village of Gazurgah, stands the shrine also referred to as Gazurgah, built around the tomb of a Muslim saint, the Khoja Abdullah Ansari. Best described in an excellent monograph by L. Golombek (The Timurid Shrine at Gazur Gah, Toronto, 1968), the shrine is one of the most complex architectural and artistic monuments in the Islamic world. (See 65 and colour plate 22.)

Gazurgah means ‘bleaching ground’, although some authorities would prefer to interpret it as ‘site of a battle’. It lies at the foot of the mountain known as Zanghir Gah, which is part of the chain running east to west, along the southern slope of which flows the Hari Rud. Since part of the oasis has been relatively well watered it has always been a favourite site for gardens, palaces and burials of prominent Herati personalities. Already before the tenth century, medieval historians mention a shrine on the the slopes of Zanghir Gah.

It was the teacher of Khoja Ansari, Sheikh Amu, who established a khaniga (khanaqah) at Gazurgah and thereby raised it from a minor sanctuary to a flourishing centre of Muslim learning. Sheikh Amu died in 1049, and Khoja Ansari became, in his turn, the leading personality among the Sufis of north-eastern Khorassan. He was a philosopher and mystic, and soon after his death in 1089 became venerated as a saint.

According to literary sources, a madrasa was built at Gazurgah in the Ghorid period, in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, and there was at least one royal burial at the site.

Most of the present shrine goes back to two periods in the fifteenth century. Originally built by Shahrukh in the years 1425–26, it was heavily damaged in a disastrous flood in 1493; Ali Shir Nevai, the vazir of Husayn Baykara, repaired and rebuilt it in 1499. Some later additions were made under the Safavids, while the Chinghizid khans in the seventeenth century added some interior decoration and restored and reconstructed parts of the complex.

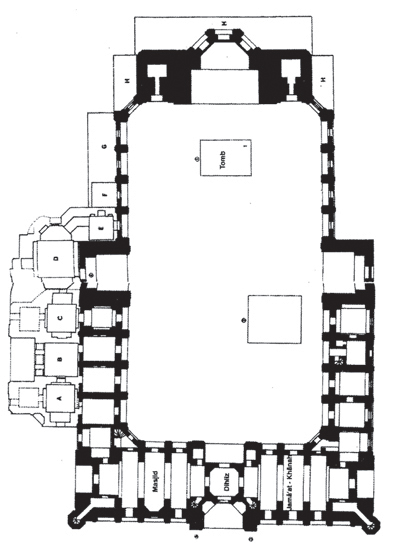

Fig. 32 Gazurgah. A, B & C First additions; D & E Second additions; F, G & H Modern additions

The shrine itself consists of an entrance iwan framed by a high portal screen and flanked on either side by an arcade terminated by a corner turret. Behind it, to the east, is a rectangular courtyard framed, on the north and south sides, by arcaded wings with an iwan in the centre of each side. The east side is formed by a monumental iwan with a mammoth portal (pishtak) in front of which lies the tomb of the khoja. The entire surface of the courtyard is densely covered with tombstones representing ‘one of the richest graveyards in the East’.14

The west wing of the shrine contains, first and foremost, the entrance complex consisting of the main portal, or iwan, facing the forecourt, the vestibule behind it and another iwan facing east into the inner courtyard. On each side of the vestibule is a large room, a mosque on the north side and an assembly room on the south side. Each of these two rooms, the proportions of which are similar, has direct access from the outside through lesser portals on the north and south sides of the outer façade.

The entrance portal consists of a five-sided bay covered by a semi-dome joined to a portal screen. The decoration is mainly in turquoise and black glazed tiles, with medallions executed in mosaic faience. The large inscription frieze that frames the portal screen has been added in the seventeenth century.

The interior of both the mosque and the assembly room displays a striking architectural décor. Their ceiling consists of a complex system of plaster vaults, semi-domes and transverse arches with fan-shaped plaster mukarnas in the domes between the arches. The entire interior is white, except the lower part of the walls, which are decorated with a wide band of buff-coloured tiles lined with black and blue mosaic faience and set in a simple geometrical pattern.

Seen from the courtyard, the north wing consists of a central iwan flanked on either side by a façade with four arcaded recesses, or niches.

The decoration of the iwan is preserved mainly on the inside wall, and consists of large geometrical patterns in glazed bricks (banai-technique). Parts of an inscription frieze in mosaic faience still exist on the outer wall, and there is a well-preserved panel in the same technique above the entrance.

One more room should be mentioned on this side of the courtyard. It is a mud-brick construction added in modern times, which can be entered by a door in the curtain wall east of the iwan. Inside is the famous cenotaph of carved black stone known as the Haft Qalam or Seven Feathers. According to Golombek, it is ‘one of the most intricate and delicate carvings ever created by the Iranian world’.

Like the north wing, the south wing consists of a central iwan and an arcaded façade, the eastern part of which is just a curtain wall, while behind the western part is a series of rooms, the size and layout of which more or less corresponds to its northern counterpart. Generally speaking, the structures on the south side are much more damaged, especially the rooms and roofs nearest to the south-western corner. No interior decoration survives. Most of the decoration on the façade is in a poor state too. The interiors of some of the rooms were reconstructed to the extent that it is difficult to determine the original layout. There were no later additions on this side.

The eastern iwan is the most imposing part of the shrine. The pishtak, some 100ft high, is visible from afar. It was originally completely covered with ornaments of glazed tiles, but unfortunately much of it has disappeared. Inside the iwan, however, ‘the surfaces have preserved some of the richest and most imaginative glazed tile compositions ever created’.15 The bay in the back of the iwan is decorated in the lower part with rectangles consisting of an arched panel with a square above it; the middle part is formed by a large inscription frieze in what looks like Kufic script but is, in fact, a ‘rare example of Naskhi script executed in banai-technique’.16 The semi-dome above it is filled with stars and polygons, a favourite motif symbolising the dome of heaven.

The vault of the iwan is separated from the bay by an arch decorated with an inscription frieze. The inscription, executed in beautiful two-line Thulth, continues horizontally along the sides of the iwan. The upper section, or arch, of the iwan is covered with a kaleidoscopic design consisting of small geometric units, squares, rhomboids and triangles, centred around a hexagon and fitted together to form a larger design. The hexagons are decorated with floral and arabesque motifs, the rhomboids bear the word ‘Allah’ in stylised Kufic etc. The lower section is equally remarkable. It consists of squares and rectangles made up of minuscule simulated brick-ends featuring imaginative epigraphic themes in alternating colours. The whole design is framed by a wide band in the same pseudo-Kufic script as in the bay, endlessly repeating the same evocation of God.

The tomb of Khoja Ansari is in front of the eastern iwan, hidden behind a lattice-work structure. North of it stands a 16ft-high ornamental marble column adorned with inscriptions and stucco mukarnas, which was erected in 1454. Next to the column is the tomb of Amir Dost Mohammed, who died in Herat in 1863 in the course of a military campaign.

Among the many tombstones in the yard, the most imposing is the large rectangular platform in front of the southern iwan known as the Takht or Throne. Built by Husayn Baykara in 1477–78, it is decorated with a pattern of white marble inlaid with black along the sides. On the platform itself are six cenotaphs of black belonging to the sultan’s family (his father, uncle and brothers). Another black marble stone, elaborately carved but undated, lies opposite the north-western corner of the platform.

Immediately west of the shrine complex two buildings should be mentioned, the Zarnigar-Khana and a pavilion called Namakdan, the Salt Cellar. The main entrance to Zarnigar-Khana is through a large iwan on the north side, facing the forecourt, in which remains of elaborate decoration in tinted plaster can be seen. The outer façade is bare. Inside is a large domed hall, some 30 square feet, with a mihrab in the western wall. The transition zone between the dome and the walls and the dome itself are covered with gold and blue paintings remarkably well preserved.

Some of the floral motifs in the paintings are similar to those found on the carved tombstones of the ‘haft qalam’ type executed in Herat toward the end of the fifteenth century. A common inspiration for both is seen by some scholars in carpet designs that go back at least to the beginning of that century, and have as their ultimate source Chinese silks.17

The decoration of the Zarnigar-Khana dates in all probability from the very end of the fifteenth century. It is possible that the structure itself was erected somewhat earlier. It now houses a local school. The Namakdan is a garden pavilion twelve-sided on the outside and octagonal on the inside. The central octagon is covered by a star-vault composed of interesting plaster ribs. There is no other decoration. It was probably built in the seventeenth century, and is at present used as a guest house by the administrator of the shrine. There is evidence that a similar pavilion stood some 100 yards further west.

The covered cistern, Zamzam, was restored in the year 1683 or 1684. An inscription attributes its original foundation to Shahrukh, who is believed to have brought water for it from the holy well in Mecca.

The inscription, which is in the form of a poem, not only compares the cistern with the Zamzam of Mecca but alludes to the shrines of Hebron and of Medina, which also appear in the paintings of the vestibule. It is therefore highly probable that these paintings were executed at the same time as the cistern.

The underground mosque, just west of the cistern, consists of a dome chamber and deep recesses leading to small meditation cells. The vault of the chamber is probably of the Timurid or Safavid period.

About 60 miles further east up the valley we come to one of the most famous monuments of Afghanistan and, indeed, of the whole Islamic world, the minaret of Jam. The road is difficult to find, and can only be negotiated by Jeep or Land Rover. After the village of Shahrak, a track to the left leads to the river, where the minaret stands in complete isolation. It was only discovered in 1957 by a French archaeological expedition, although rumours of its existence had been circulating for some time. With its height of 215ft it ranks second in the Islamic world, after the Kutub Minar in Delhi (241ft). It consists of a low octagonal base some 26ft across, and three cylindrical stages; the first is decorated with geometrical patterns in fired bricks arranged in panels separated by vertical bands of Kufic inscriptions. A wide horizontal band of blue tiles with a Kufic inscription runs around the top of the first stage. In it, a line of Naskhi gives the name of the calligrapher as ‘Ali’. The second and third stages are decorated with horizontal bands of inscriptions, again in fired bricks. The stages were originally separated by galleries, which have not survived. The top was closed by a lantern, which has also collapsed. An interior staircase leads up to the second stage. The inscriptions confirm that the minaret was erected by Sultan Ghiyat ud-Din Muhammad ben Sam, the ruler of Ghor. It was built, in all probability, between 1193 and 1202.18 (See p.211.)

Full details of abbreviations and publications are in the Bibliography

1 Le Strange, G., The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate, p.409.

2 Le Strange, The Lands, p.409.

3 Byron, R., Road to Oxiana, p.103.

4 Lewis, B. (ed.), Islam, pp.66–67.

5 Melikian-Chirvani, A.S., ‘Eastern Iranian Architecture’, BSOAS XXXlII, 1970.

6 Byron, Oxiana, p.85.

7 Wilber, C.N., The Architecture of Islamic Iran, p.35.

8 Sourdel-Thomine, J., ‘Deux minarets de l’epoque seljoukide en Afghanistan’, Syria, XXX, p.108.

9 Byron, R., ‘Timurid Monuments in Afghanistan’, IIIe Congrès International d’art et d’archeologie iraniens, 1935.

10 Byron, Oxiana, p.96.

11 Renz, A., Geschichte und Statten des Islam, p.468.

12 Wolfe, N.H., Herat, a Pictorial Guide.

13 Golombek, L., The Timurid Shrine at Gazur Gah, p.90.

14 Golombek, Gazur Gah, p.28.

15 Golombek, Gazur Gah, p.45.

16 Golombek, Gazur Gah, p.45.

17 Golombek, Gazur Gah, p.66.

18 Auboyer, J., Afghanistan, p.162.