THE AMERICAN EXTRA PHARMACOPOEIA

DAVID WINSTON

THE AMERICAN EXTRA PHARMACOPOEIA

DAVID WINSTON

In China the traditional pharmacopoeia of plant, mineral, and animal drugs is vast, containing over a thousand remedies; the same is true of India’s Ayurvedic system of medicine. Other ancient and equally successful indigenous systems, such as the Ani Yvwiya (Cherokee) Nvwoti, Japan’s Kampo, the Tibetan So-wa Rig-pa, and the Unani Tibb system, also use a large number of botanical drugs. Conversely, in the United States and Great Britain there is a trend toward relying on an ever dwindling materia medica. Possible reasons for this situation are many:

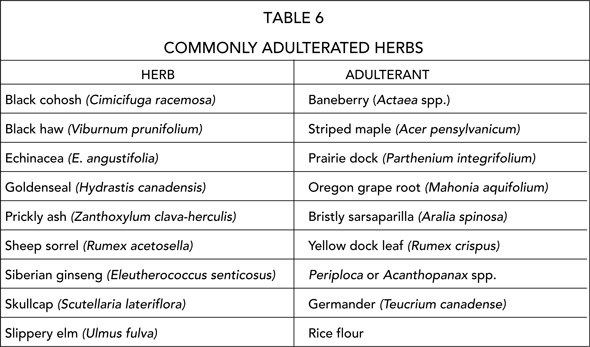

Our reliance on so small a pharmacopoeia can and has caused certain problems to develop. Many once-common herb species are now threatened or endangered, or are becoming increasingly scarce and costly. These include ginseng (Panax quinquefolium), lady’s slipper (Cypripedium spp.), slippery elm (Ulmus fulva), goldenseal (Hydrastis can ad ens is), gentian (Gentiana spp.), false unicorn root (Chamaelirium luteum), and bethroot (Trillium erectum). With the demand for these popular botanicals increasing and the supply shrinking, the chances of adulteration and/or spurious substitution increase.

As our materia medica shrinks, so do our options for treatment. The tendency of self-limitation creates practitioners who rely on the ten or twenty “most valuable herbs.” The assumption is that this small number of botanicals is sufficient to cope with any disease or complaint.

This is all the more ironic when you realize that in the past, the average Cherokee layperson knew and used one to two hundred medicinal herbs, while a medicine person would be knowledgeable in more than eight hundred. How many of us can honestly say we are intimately familiar (taste, energy, usage, taxonomy, chemical constituents, and so on) with even one hundred herbs?

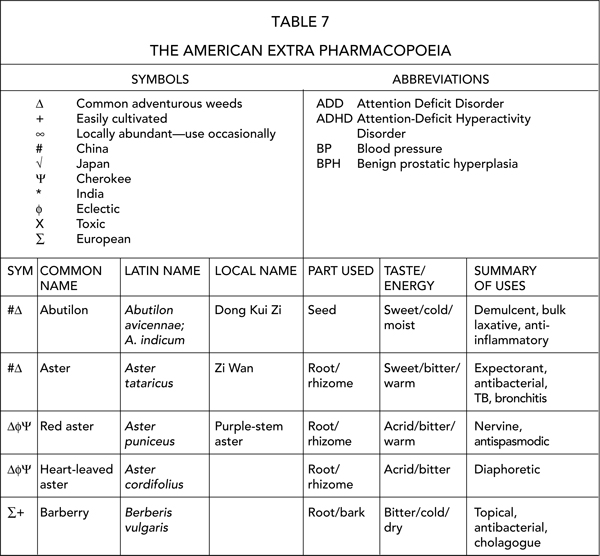

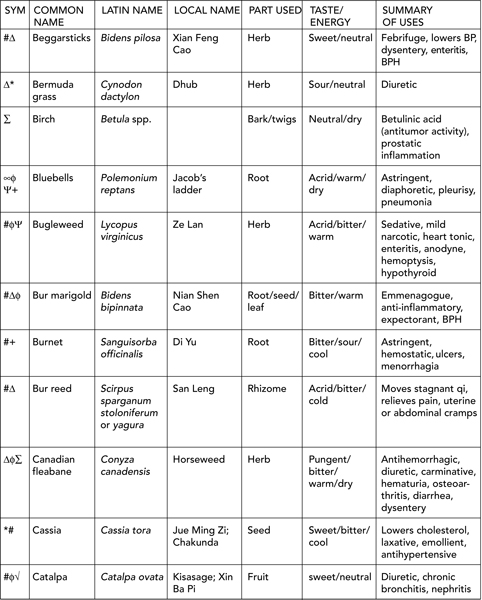

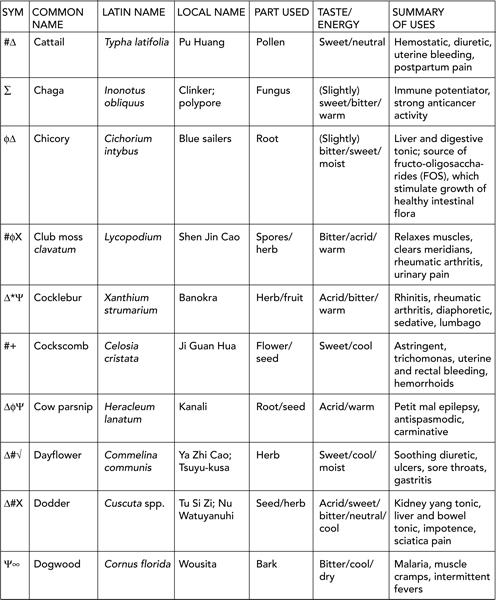

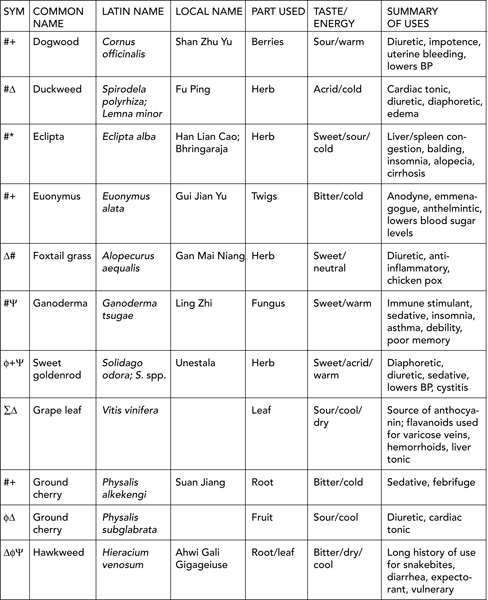

One way to correct this problem is to expand our locally available pharmacopoeias by the inclusion of unused but effective indigenous and introduced species. There are hundreds of such herbs available that have long histories of usage by peoples who depended on them for health and well-being. With a few exceptions, the plants on this list are little known and rarely used in this country; still, they are or once were commonly used throughout the world. Most species discussed are classified as adventurous, hardy weeds that are common throughout much of the United States and are abundant and easily procured while fresh and still potent. Many are considered noxious weeds. Millions of dollars are spent and thousands of pounds of toxic chemicals are applied yearly by farmers and lawn care providers in order to eradicate these helpful plants. The use of such herbs curbs their relentless spread, reduces the need to use polluting herbicides, and helps maintain sensitive ecosystems threatened by these aggressive foreign weeds. Creating and educating the public and practitioners about the American Extra Pharmacopoeia (AEP) will broaden our knowledge, enhance our clinical practices, and help create a system of planetary herbal medicine that is effective and ecologically sound.

THE AMERICAN EXTRA PHARMACOPOEIA

GROUND IVY

Latin name: Glechoma hederacea

Chinese name: Lian Qian Cao (Glechoma longituba)

Common names: Gill-over-the-ground, alehoof

Part used: Fresh or dried herb

Taste: Bitter

Energy: Cold and dry

Constituents: L-pinocamphone, L-menthone, L-pulegone, d & ß pinene, limonene, ursolic acid

Action: Antiviral, cholagogue, expectorant

Dosage: Tea—Add 1 teaspoon of dried herb to 8 ounces of hot water. Steep, covered, for half an hour. Drink one 4-ounce cup three times per day. Tincture—1:2 fresh extract, 20-40 drops (1-2 ml), three times per day.

An aggressive garden and lawn weed, ground ivy has a long history of use throughout Europe and China. The Chinese use a closely related species (Glechoma longituba) to clear toxic heat for conditions such as jaundice and cystitis, and to help expel urinary and biliary stones. Recent research shows that the herb stimulates an increase in bile secretion and movement of the gallbladder sphincter. Ground ivy is also used topically to dispel blood stasis and for traumatic swellings such as sprains, bruises, and infections. European use parallels traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) usage as a liver/gallbladder and digestive herb, with additional activity based on the herb’s antiviral and expectorant properties. It is effective for bronchitis, pneumonia, hot damp coughs, and chest colds.

JAPANESE KNOTWEED

Latin name: Polygonum cuspidatum

Chinese name: Hu Zhang

Part used: Dried root and leaf

Taste: Bitter

Energy: Cold and dry

Constituents: Anthraquinones and anthraglycosides, primarily emodin, rhein, chrysophenol, resveratrol, and tannins

Action: Astringent, antitumor, antibacterial, laxative, emmenagogue, expectorant

Dosage: Tea—Add 1 teaspoon of the dried root to 8 ounces of water. Decoct for ten minutes, or longer if you want to decrease the laxative effect Steep for half an hour. Drink one 4-ounce cup of tea twice per day. Tincture—1:5, 40 percent alcohol, 20-30 drops (1-2 ml), twice per day.

The roots and leaves of this highly invasive weed are used in TCM to eliminate damp heat—dysentery, jaundice, appendicitis, hepatitis, and enteritis. It also promotes circulation of blood (xue), relieves pain, and is used orally and topically for snakebite, rheumatoid arthritis, burns, trauma injuries, abscesses, and boils. It has antibacterial and expectorant qualities, making it useful for bronchitis, pleurisy, and other damp-heat lung infections. Two constituents in Hu Zhang, rhein and emodin, have shown strong antitumor activity both in vitro and in vivo. A third ingredient, resveratrol, is a powerful anti-oxidant. This combination makes this herb a potential choice for cancer protocols. Excess amounts of the root can cause diarrhea and/or rebound constipation.

KUDZU

Latin name: Pueraria lobata

Chinese name: Gegen

Part used: Dried root, root starch, and flower

Taste: Sweet, pungent

Energy: Cold and moist

Constituents: Isoflavones, including puerarin, diadzein, and diadzin

Actions: Antihistamine, anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, and demulcent

Dosage: Tea—Add 2 teaspoons of the dried root to 8 ounces of water. Decoct for thirty minutes. Steep for thirty minutes. Drink one 4-ounce cup three times per day. Tincture—1:5, 30 percent alcohol, 40-60 drops, three times per day (not appropriate for reducing alcohol cravings). Capsule—Two capsules twice per day.

Kudzu was introduced into the United States in the 1880s as an important and versatile economic plant. Later, in the 1930s, it was promoted as a way to control erosion. As a means of controlling and preventing erosion, the plant is indeed an incredible success. It is also successful in destroying native herbs, shrubs, and trees, and creating environmental havoc throughout the southeastern U.S.

The way to control this highly aggressive plant is to use it, a lot of it. Multiple parts of the plant can be used for medicine, food, animal fodder, and fiber. The root is used as a tea in TCM for colds and flu with fever, dry mouth, headaches, and muscle stiffness in the head and back. It is also useful for head colds, sinus congestion, and sinus headaches. Its antispasmodic actions make it effective for torticulis (wry neck), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea, and ischaemic heart disease, especially angina. Recent research on kudzu found that the decoction of the root reduces alcohol cravings in Syrian golden hamsters, and has a similar effect in humans. In China the flowers were traditionally used for a related purpose—alcohol poisoning (hangovers).

Other parts of the plant have uses as well. The leaves can be eaten as fodder, especially by goats, and they are used as poultices for wounds. The root starch is used as a thickening agent for foods in Japan, as well as a medicine in the macrobiotic diet. Finally, the stems can be used to make fiber and can be woven into beautiful and durable baskets.

PURPLE LOOSESTRIFE

Latin name: Lythrum salicaria

Common name: Purple loosestrife

Part used: Dried flowering herb

Taste: Sour

Energy: Cool, dry, and moist

Constituents: Vitexin (a glucoside), salicarin, tannins, pectin

Action: Antibacterial, antiamoebic, astringent, demulcent, anti-inflammatory, anti-hemorraghic, antihistamine, antispasmodic

Dosage: Tea—Add 1-2 teaspoons of the dried herb to 8 ounces of hot water. Steep for one hour. Drink 1-3 cups of tea per day. Tincture—1:5 dry extract, 30 percent alcohol, 40-60 drops (2-3 ml) three to four times per day.

Originally planted as a perennial ornamental for its lovely purple-magenta flower spikes, purple loosestrife quickly wore out its welcome. It likes wetlands and now covers hundreds of thousands of acres, choking out native plants and the species of animals and insects that depended on them for food and habitat. Once commonly used in European herbal medicine, we need to utilize this weed again both for its valuable medicinal qualities and to reduce its invasive spread. Upon first taking Lythrum, you will notice a pronounced astringency, later followed by a soothing demulcent quality. This combination of actions, along with others, makes this plant appropriate for diarrhea, bacterial or amoebic dysentery, enteritis, IBS, leaky gut syndrome, and sore throats (as a gargle). Maude Grieve, in her book A Modern Herbal, says “that as an eyewash Purple Loosestrife is superior to Eyebright for preserving the sight and curing sore eyes.” Current European uses of this herb include the treatment of ophthalmic ulcers. The herb can also be used as a vaginal douche for leukorrhea and bacterial vaginosis, and as a nasal douche for nosebleeds. Topically the ointment is used for ulcers and sores; a poultice is soothing to bruises, abrasions, and irritated skin. The stems can be chewed for bleeding gums caused by pyorrhea and gingivitis.

SELF-HEAL

Latin name: Prunella vulgaris

Chinese name: Xia Ku Cao

Common name: Allheal, heal-all

Taste: Bitter, slightly pungent

Energy: Cold, slightly moistening

Part used: Dried flower spike and leaf

Constituents: Saponin (a triterpenoid), rutin, hyperoside, caffeic acid, d-camphor, and d-fenchone

Action: Antibacterial, antimutagenic, diuretic, hypotensive agent

Dosage: Tea—Add 1-2 teaspoons of the dried herb to 8 ounces of hot water. Steep for one hour. Drink 2-3 cups per day. Tincture—1:2 fresh extract, 30 percent alcohol, 40-60 drops, (2-3 ml), three times per day.

Self-heal is a small member of the Lamiaceae (Mint) family commonly found in lawns and waste areas. It has attractive spikes of purple flowers but is considered a nuisance weed. Once known as allheal, it is now little used in Europe and the United States but maintains a place in the Chinese materia medica. In TCM Xia Ku Cao is used to soften hardness (lumps, enlarged lymph nodes). It is also used for goiters, lipomas, mumps, mastitis, lymphosarcoma, and scrofula. In addition, it is used for pathological heat in the liver (liver fire rising). These conditions include liver fire headaches, acute conjunctivitis, hypertension, vertigo, and painful or light-sensitive eyes. Topically, self-heal is used for inflamed wounds that are red and painful to the touch as well as hot (fire poison)—boils, carbuncles, sties, and staph infections. Keeway-dinoquay, an Anishnabe elder, says that self-heal is exceptionally effective as a compress for removing splinters of wood, metal, or glass.

SPICEBUSH

Latin name: Lindera benzoin

Cherokee name: Nodatsi

Common name: Spicewood

Part used: Dried bark, leaf, fruit

Taste: Pungent and sweet

Energy: Warm and dry

Constituents: Linderol, linderone, linderalactone

Action: Antiseptic, carminative, diaphoretic, emmenagogue, expectorant

Dosage: Tea (bark/leaf)—Add 1 teaspoon of the dried bark or leaf to 8 ounces of hot water. Steep (covered) for one hour. Drink 2-3 cups per day. Tincture—1:5 (dry) extract, 40 percent alcohol, 30-40 drops (1-2 ml), three times per day.

Spicebush is one of the most common under-story shrubs throughout second- or third-growth eastern forests. Early in the spring it is covered with small yellow flowers, which perfume the air. Every part of spicebush is medicinal; the tea of this herb is used extensively for colds, flu, coughs, nausea, indigestion, croup, flatulence, and amenorrhea. The inhaled steam is used to clear clogged sinuses, and the decoction of the twigs makes a soothing bath for arthritic pain (some of the tea is also taken internally). A related species of spicebush, L. strychnifolia, is used in TCM for dysuria, fungal infections, asthma, dysmenorrhea, hernia pain, and diarrhea. Spicebush is also commonly used as a beverage tea, and the dried fruits can be used as a spice in baking.

SUMAC

Latin name: Rhus glabra, R. copallina, R. typhina, R. aromatica

Cherokee name: Qualagu

Common name: Staghorn sumac

Part used: Dried berry, bark

Taste: Sour

Energy: Cool, dry

Constituents: Bark—Gallic acid. Berries—Citric acid.

Action: Alterative (bark), antiseptic, astringent, diuretic

Dosage: Tea (berry)—Add 1 teaspoon of the dried fruit to 8 ounces of hot water. Steep for thirty minutes. Drink 2-4 cups per day. Tea (bark)—Add ½ teaspoon of the dried bark to 8 ounces of water. Decoct for fifteen minutes. Steep for one hour. Drink one 4-ounce cup twice per day. Tincture (bark)—1:5 dry extract, 30 percent alcohol, 10 percent vegetable glycerine, 20-30 drops (1-2 ml) three times per day. Tincture (berry)—1:5 dry extract, 30 percent alcohol, 10 percent vegetable glycerine, 40-60 (2-3 ml) three times per day.

Sumacs are small shrubby trees that bear highly visible clusters of bright red berries each autumn. Their toxic relative, poison sumac (R. vernix), has white fruit and prefers swampy areas to the dry, open environment where other sumacs are found. Sumac berry tea is effective for urinary tract infections (it acidifies the urine), thrush, apthous stomatata, ulcerated mucous membranes, gingivitis, and some cases of bed-wetting (irritated bladder). The fruit tea can be taken hot or chilled as a refreshing beverage similar in taste to hibiscus or rose hips. The bark is a strong astringent (used for diarrhea and menorrhagia) that affects the female hormonal system. The Cherokee used the bark for alleviating menopausal discomfort (hot flashes, sweating) and as a galactogogue. Externally the berry or bark tea has been used as a wash for blisters, burns, and oozing sores.

The Eclectics used the bark of fragrant sumac (R. aromatica) for urinary incontinence, interstitial cystitis, and profuse clear urination associated with diabetes; some physicians felt it helped control diabetes as well.

REFERENCES

A Barefoot Doctors Manual. Seattle: Cloudburst Press, 1977.

Bensky, D., and A. Gamble. Chinese Herbal Medicine Materia Medica. Seattle: Eastland Press, 1986.

Bianchini, E., and E Corbetta. Health Plants of the World. New York: Newsweek Books, 1975.

Boik, John. Cancer & Natural Medicine. Princeton, Minn.: Oregon Medical Press, 1996.

Chiej, R. The MacDonald Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants. London: MacDonald, 1984.

Dastur, J. E Medicinal Plants of India & Pakistan. Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala, 1970.

Duke, J. A., and E. S. Ayensu. Medicinal Plants of China. Algonac, Mich.: Reference Pub., 1985.

Felter, H. W., and J. U. Lloyd. Kings American Dispensatory. Vols. 1 and 2. Portland, Oreg.: Eclectic Med. Pub., 1983.

Fernald, M. L. Grays Manual of Botany. 8th ed. New York: American Book Co., 1950.

Foster, S., and Yue Chongxi. Herbal Emissaries. Rochester, Vt.: Healing Arts Press, 1992.

Garg, S. Substitute and Adulterant Plants. Delhi: Periodical Exports Book Agency, 1992.

Grieve, Mrs. Maude. A Modern Herbal. New York: Hafher, 1967.

Him Che Yeung. Handbook of Chinese Herbs & Formulas. Vol. 1. n.p.: author, 1985.

Hobbs, C. Chinese Herbs Growing in the Western US. Los Angeles: author, 1985.

________. Medicinal Mushrooms. Santa Cruz, Calif.: Botanica Press, 1995.

Hsu, Hong-Yen. Oriental Materia Medica. Long Beach, Calif.: OHAI, 1986.

Lad, Vasant, and David Frawley. The Yoga of Herbs. Santa Fe, N.M.: Lotus Press, 1986.

Li Ning-hon, ed. Chinese Medicinal Herbs of Hong Kong. Vols. 1-5. Hong Kong, 1983-1986.

Lou Zhicen. Color Atlas of Chinese Traditinal Drugs. Vol. 1. Beijing: Science Press, 1987.

Munz, Philip. A California Flora. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962.

Radford, A., H. Ahles, and C. R. Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1973.

Tsanusdi, Tawodi. Personal communication with author, 1980-1998.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Selected Weeds of the United States. Agriculture Handbook 366. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1976.

Xu Xiang Cai. The Chinese Materia Medica. Vol. 2 of The English-Chinese Enyclopedia of Practical Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 1990.