Anglo-Saxon

It seems improbable that the early Germanic peoples had no tradition of masking at all. But they were an oral, not a literate, culture, and our evidence is about as sparse as it can be. What there is belongs to the warrior élite, and suggests inevitably that masking was solely connected with the practice and (possibly) rituals of warfare. If the Anglo-Saxons had a tradition of folk masking, they have left no evidence of it.

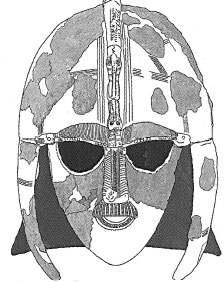

They had a word for ‘face-mask’, grīma.1 It turns up in the almost exclusively warrior context of the grīmhelm, the masked helmet long known from Beowulf and several other Anglo-Saxon heroic poems,2 which was given vivid substance by the Sutton Hoo excavations. The seventh-century helmet unearthed in that ship-burial and painstakingly reconstructed by the British Museum seemed almost magically to embody the grīmhelm of the scholars’ imagination.3 Even so, it is not specifically a Germanic style of armour, as it seems to be based on the Roman parade or circus helmet which sometimes bore a full stylised portrait mask;4 though the poets speak of the grīmhelm in a matter of fact way, as if it were a standard piece of comitatus equipment, albeit one worn in the legendary past rather than the present. We do not of course know if they were thinking of the full face-mask known only from Sutton Hoo, or of the variously visored helmets known from other Germanic burials.5 There is not the slightest suggestion in the poems that these helmets were used for anything but military purposes,6 though some of their decoration, notably the ‘boar-images above the cheek-protectors’, seems to have been prophylactic.7

The primary function of these visors must have been protective: but the artistry which has gone into their decoration, and, in Sutton Hoo, the creation of an impassive surrogate metal face to cover the warrior’s vulnerable human one, suggests something more than this. This may well be a secondary effect rather than a primary intention: the instinct to ornament may have led to the creation of an object which thereupon acquired meaning in its own right. As such it looks forward to the tournament helm discussed in a later chapter. Unlike the tournament helm, however, it does not completely conceal the person beneath. Like all masks, when it is not being worn it tells only half the story, and its effect in action may have been rather different from the hieratic (and even ‘ritual’) air it holds when at rest. Photographed on a display stand it looks remote and brooding, its empty eye-sockets unreadable. Imagine a pair of live human eyes instead. For the mask-maker, the moment when the actor puts on his creation is the moment it ceases to be a piece of sculpture and acquires an unexpected (and sometimes malign) life of its own. Encased in this carapace, the warrior might be transmuted into a hideously animated killing machine. Conversely, the helmets which only provide eye-and cheek-protection may have emphasised the vulnerability of the face beneath (a half-mask creates a completely different effect from a full mask): but even the eighth-century Coppergate helmet,8 with only a nasal and cheek-guards, shares with surviving Swedish helmets the ornate eyebrows which must have produced an unsettling change of focus, as if the warrior’s face had begun to harden into metal.

FIG. 1: The Sutton Hoo Helmet

What exactly were the contemporary connotations of a helmet mask like this? As we might expect, the vocabulary suggests aggression and (in the beholder) fear. The noun grīma may be related etymologically to the adjectives grimm ‘ferocious’, and gram ‘enraged’, also used as an epithet of the devil. Its other meaning seems to be ‘frightening creature, spook’,9 possibly even, in a biblical context, ‘devil’.10 Grīmhelm might therefore mean either ‘visored helmet’ or ‘terrifying helmet’. This seems very far from festivity or play.

The Sutton Hoo helmet has however been linked by writers on Germanic mythology and on folk custom with something which might be described as a sport, or more portentously as a ritual, and which may perhaps be associated with masks. One of the repoussé designs on its decorative plaques shows two men in horned headdresses with flared cheek-or possibly neck-guards standing, or perhaps dancing (their feet are oddly pointed), side by side. Each brandishes a sword and a pair of throwing-spears. Their expressions are blank, but this seems the effect of stylisation rather than an attempt to represent a mask.11 Another, apparently stark naked except for a belt, stands on a seventh-century gilt-bronze buckle dug up in Kent;12 another from the same period on a bronze matrix for a Sutton-Hoo-type helmet-plaque found in Torslunda in Sweden; and vestiges of other versions of the same motif exist, mostly associated with helmet decoration and mostly Swedish, though some have been found, as amulets or decorating vessels, in female burials in both Sweden and England.13 This last fact has reinforced the idea that they are of cultic significance, possibly connected with the worship of Woden, rather than simply suitable decoration for a warrior’s war-gear.

FIG. 2: The Finglesham Buckle

They have been identified with a sporadically recorded weapon-dance which was enthusiastically linked by E.K. Chambers with ancient sacrificial ritual practices, and hailed as ancestor of the modern morris sword-dance.14 Tacitus, in AD 98, mentions a dance by naked young German warriors inter gladios … atque infestas frameas (‘among swords and hostile spears’). There is no suggestion, however, that it is other than a ‘public show’ (spectaculum) or ‘game’ (ludicrum), performed for the pleasure (lascivia, voluptas) of the dancers and their audience, and he does not mention masks.15

Eight centuries later, Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos, writing on the ceremonies of the Byzantine court, describes a curious Christmas-time dance traditionally performed by the ‘Gothic’ guards in the service of the Emperor.16 Two pairs of Goths, dressed in γoυvασ (tunics made of skins) with the fur on the outside,17 and perhaps wearing masks (πρoσωπα διαϕoρωειδεων, ‘faces of various sorts’) danced, accompanied by panduras,18 to a curious Gothic song (Γoτθικα), punctuating it by beating on their shields with a stave and chanting ‘Tul! Tul!’ But before we start imagining pagan rituals, we should remember that by this time the Goths19 had been Christian for nearly 600 years. Whatever the original purpose of the dance, by now it is an interesting but alien calendar custom observed by the sophisticated Byzantine court with possibly the same mixture of emotions as a Twickenham crowd at a rugby international watches the New Zealand All Blacks perform their haka. Presumably the purpose of the masks, if they were masks, and were an original part of a warrior dance, was the same as that of war-paint. The warrior hopes to make himself terrifying to the enemy, while by changing his outward appearance he also shifts his own peaceable persona to his warrior alter ego. The psychological effect benefits the wearer as much as it disadvantages his target.

This desire to change personality, even, for the duration of the battle, to discard humanity and become a predator, may lie behind the figures of the Scandinavian berserkir and úlfheðnar (‘wolf-skins’), which is perhaps reflected in some of the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary for warrior: beorn (‘bear’), freca (‘greedy one’, wolf), wœl-wulf (‘carnage-wolf’). On the same Torslunda stamp, the dancing spearman is followed by a mysterious creature with an animal’s head, possibly a bear’s, and a tail, but clothed and with distinctly human feet and legs. It also carries a spear, and appears to be drawing a sword. It might be an attempt to show a warrior possessed by his totem animal in this way, or it might, naturalistically, depict a masked dance, designed to give the dancer the qualities of the animal it represents, and possibly to stir up a trance-like battle-frenzy.20 On the other hand, Plutarch, writing in AD 105–115, says in his ‘Life of Caius Marius’ that the horsemen of the Germanic Cimbri and their confederates, who invaded Italy in 102 BC, wore ‘helmets made to resemble the maws of frightful wild beasts or the heads of strange animals, which, with their towering crests of feathers, made their wearers appear taller than they really were’.21 This sounds a purely pragmatic type of psychological warfare. Earlier the foot-soldiers are said to go into battle ‘rhythmically clashing their arms and leaping to the sound’, shouting their tribal name ‘Ambrones’ in unison, which may give us a glimpse of the reality for which the sword dance was a training.22 But we have no proof of a link between the helmet decorations and the dances in Tacitus or in Constantine VII except for a general Germanicness; and the visual images, though suggestive, remain elusive and enigmatic.

FIG. 3: Torslunda Plaque

The last often-cited appearance of the Germanic sword- and spear-dance is in 1555, when Olaus Magnus, Bishop of Uppsala, describes one performed by the septentrionales Gothi et Sueci (‘Northern Goths’, i.e. from the southern Swedish peninsula and the island of Gotland, ‘and Swedes’). Verbally this sounds suspiciously like Tacitus, save that the swords rather than the dancers have become naked: inter nudos enses et infestos gladios seu frameas (‘between naked blades and hostile swords or spears’). He says that this is danced ‘especially at the time of Carnival, or in the Italian term, “of masks/masquerades’” (praecipue tempore carnisprivii maschararum Italico verbo dicto). At first this may sound as if the dancers wore masks, but in fact Olaus Magnus, who was living in exile in Rome at the time, is merely giving a local term for the carnival season.23

This is the sum total of our solid evidence for Anglo-Saxon masking and its possible Germanic context. Both artefacts and dances appear to be connected with the art of war. There is nothing to suggest that ordinary people in Anglo-Saxon England went in for masked dancing, recreational or ritual. The surviving literature talks enthusiastically about music, tale-telling, drinking, and field sports, but that is all.

Yet these scraps of data continue to tantalise with the promise that there might be something more there if only we had the ingenuity to work out what it was. It is easy to see how earlier scholars, under the influence of Grimm and Max Müller, were seduced into constructing a painstakingly woven house of twigs for Anglo-Saxon paganism. The tempting methodology they evolved24 would only be of academic interest here if it were not that it has seeped through into popular imagination and become an ‘explanation’ of modern folk customs, which, it is confidently asserted, must go back to pagan times.25

To enthusiasts of this school of thought, it seems axiomatic that all folk customs, and all non-Christian decorative art must necessarily be rooted in pagan ritual, and (a further leap of faith) that this ritual can then be linked, tentatively or with confidence, with the gods of Germanic mythology. This hypothesis then provides a structure into which we can satisfyingly slot our nuggets of information. The animal-headed creature with human feet, apparently drawing a sword, on the Torslunda stamp must be a berserkr taking part in a ritual dedicated to Woden/Óðinn, the god of war, trickery, and the dead. Because Óðinn in later Scandinavian literature appears to travel between our world and the realm of the dead in order to gain occult knowledge, and his name is said to mean furor, he must be a shaman.26 Because one of his by-names in the Poetic Edda is Grímnir, the Masked or Cowled One,27 his shamanism might have involved masking. The animal-headed creature is therefore a warrior-shaman wearing a mask.28 His companion on the stamp must be taking part in Tacitus’ naked-warrior dance, also in honour of Óðinn. This then opens up the possibility of comparisons with modern anthropological work on shamanism, particularly attractive to theatre practitioners who would like to appropriate the idea of possession by the spirit of the mask;29 and it would add a dimension to this study which is otherwise completely lacking.

But however attractively suggestive it may be, we must avoid being seduced by the vision of rituals of whose details we know nothing, and acknowledge the prosaic truth. By the time we have written evidence of the Anglo-Saxons, they are Christian. If masked folk practices of this kind existed, and if they survived the Conversion, we have no record of them.

This in itself may be significant. If there were a living, even though underground tradition, we might expect to find condemnations of it in the various law-codes30 and penitentials,31 which are very informative about other areas of superstition and misdemeanour. But though both mention heathen practices (most notably after the Viking settlements), they do not refer at all to this kind of proceeding: in fact, compared with continental penitentials and decretals, they are disappointingly mundane.32 Penance is enjoined for sacrificing to ‘idols’, largely trees, wells, or standing stones, or for practising various kinds of charm – love philtres, death-spells, cures – and auguries and other superstitions; but no-one suggests that masked figures are slipping out through the moonlight to celebrate the winter solstice,33 or worshipping the old gods by dancing in animal disguise. Those seeking for traces of ancient mystery will have to look elsewhere.

Most of the supposed ‘evidence’ for the native pagan antiquity of masked British folk calendar customs, such as mumming and guising, in fact belongs to a completely different, Mediterranean tradition, the Roman festival of Kalends. Its apparent transplantation to Anglo-Saxon England is an illusion which owes more to the eclectic habits of clerical copyists than to actual native practice. For example, the so-called Penitential of Egbert of York (c. AD 740), among several prohibitions ‘of auguries and divinations’, prescribes a penalty of five years’ penance for a cleric and three for a layman for ‘honouring the Kalends of January in conformity with heathen practice’ (Kalendas Januarias secundum paganam causam honorare),34 But this statement is taken almost verbatim from a continental penitential, which in its turn copied it from a much earlier southern European sermon. We cannot be certain that the Anglo-Saxons celebrated 1 January either as a local traditional festival,35 or, as the penitential seems to suggest, as it was celebrated three centuries earlier in Provence. We seem to be confronted with a choice of two extremes: if we cannot subscribe to the pan-Germanic theory of persisting heathen folk-practices, then we have to conclude that the later medieval New Year masking games were an importation from the Continent. Kalends masking of a sort does eventually appear in England, but only after a long and riotous career on the mainland of Europe. It is to this infinitely better-evidenced festival that we now turn.

Kalends

Medieval and early-modern authorities themselves believed that the tradition of an extended period of winter festivity went back time out of mind. Academic writers, even in Britain, saw a classical origin for the celebrations: William Prynne, the early seventeenth-century antitheatrical campaigner, exemplifies the standard parallel drawn between the Christmas and New Year festivities of his own time and the Saturnalia and Kalends festivals of classical Rome. His detailed and vituperative comparison concludes that since both are:

… spent in revelling, epicurisme, wantonnesse, idlenesse, dancing, drinking, Stage-playes, Masques, and carnall pompe and jollity … wee must needes conclude the one to be but the very ape or issue of the other.36

In spite of Prynne’s assertion, however, there is no evidence for ‘masques’ and masking at the Roman Saturnalia and Kalends festivals until the fourth century AD.37 Yet from then on, masking seems steadily to infiltrate even the most unlikely customs, so that by the fifteenth century we find dicing in masks, dancing in masks, good-luck visits in masks, even, in Italy, bull-fighting in masks. The masks do not seem to be organically related to the individual customs, but to the festivities as a whole, though once they have arrived, they can alter the entire focus and apparent meaning of the customs themselves. It is therefore worth considering the nature of these Roman festivals before they acquired this mysterious overlay.38

The Saturnalia took place officially on 17 December, though celebrations rapidly spread far beyond.39 Business of any kind was forbidden, presents were given, parties thrown, people played draughts and dice for nuts. One of the themes of the holiday was ‘the world upside-down’: for its duration slaves were treated like free men and served at table by their masters, while a Lord of Misrule (Saturnalicius princeps) was chosen on a throw of the dice.40 Lucian (c. AD 125–200), in the dialogue Saturnalia, catalogues the riotous proceedings:

… potare, inebriari, vociferari, ludere, certare tesseris, creare reges, famulos in convivium adhibere, canere nudum, lascivo corporis motu saltitare, nonnumquam et in gelidam aquam dare praecipitem, facie fuligine oblita.41

… drinking, getting drunk, shouting at the top of your voice, playing games, throwing dice, making kings, having your slaves to dinner, singing in the nude, sexy jiggling about, and as often as not ducking people head first in icy water, with a face covered in soot.

The return to Saturn’s Golden Age42 is translated into a land of Cockaigne.

The Kalends, the New Year festival, followed close behind.43 Officially marking the inauguration of the new Consuls, unofficially it was a festival of household celebrations and rituals to bring luck to the new beginning: people exchanged seasonal greetings (vota); gave gifts (strenae), often of gilded dates or honey; later, and among the wealthy, of money.44 Front doors were decked with greenery and lanterns. It was a season of good will; essentially a festival of private inaugurations and hanselling among friends and neighbours.45 The two festivals appear gradually to have run into each other.46 While the Saturnalia remained a Romano-Greek festival, the wider Roman world, which included Gaul and Spain, celebrated it as an extended Kalends.

It is against this background of winter festivity that we first hear of play involving masks. Both the facts, and the ambience, are elusive, partly because, as we will find repeatedly and often frustratingly with popular masking, the evidence comes from those who thoroughly disapprove of the practice preaching to those who know all about it. It suddenly comes into prominence in the years around AD 400, when early Christian bishops start trying to dissuade their congregations from joining in New Year celebrations which apparently included not only the traditional gift-giving and parties, but masking in feminam … aut in pecudes, aut in feras, aut in portentas (‘as women … or as farm animals, or as wild animals, or as monsters’).47

Even the natural impression that this is a new development could be wrong. It may well be that this masking had been going on for centuries, but that nobody recorded it because it was not considered either particularly offensive or particularly noteworthy. It was neither part of official cult nor a sophisticated Roman pastime: we would probably classify it as ‘folk custom’ in the nineteenth-century sense, with all the connotations of rural indigenous ‘traditional’ behaviour. It becomes the focus of attention because the Church, relatively new to official status, was struggling to make Christianity into a ‘community religion’.48 In the process it attempted to control aspects of everyday life which had previously been left unremarked. Among these were the traditional superstitions and festivities of local people – probably the most accurate translation of the word pagani49 – though the sense that they are largely practised by country-folk may be partly true.50 Hence perhaps the appearance of farm animals and wild animals among the masqueraders.

Earlier polemic against masking had been directed at the spectacula in the amphitheatre whose cruelty and tackiness could be specifically associated with the worship of the official Roman pantheon.51 It targets theatre masks, worn by professional actors, though versions of these seem also to have been worn in festive processions, especially the pompa circensis. Peter Chrysologos, preaching in Ravenna, the seat of government, in the first half of the fifth century, seems to refer to an urban Kalends procession in which even Christians from his flock wore masks representing the gods, but in order to guy them, just as carnivals in some places today lampoon political figures.52 But he also attacks an impressive range of animal and monster disguises: ‘wild beasts … draught animals … flocks and herds … demons’.53

The element of this masking that until recently attracted most attention, both scholarly and not-so-scholarly, is the animal disguise. The bishops accuse their congregations of dressing up as pecudes (‘farm animals’), ferae (‘wild animals’), and most specifically as the cervulus or Little Stag.54 Allusions to this mysterious creature, which has been adopted enthusiastically as a sort of Missing Link between the Sorcerer of Les Trois Frères and the hobby-horse,55 and thus as direct evidence of pagan survival in modern folk custom, are thinly scattered and uninformative. The earliest comes from Barcelona (c. 370) where Bishop Pacian, having written a (now lost) treatise on the Little Stag, is struck with rueful anxiety that he may actually have revived the custom he was trying to suppress:

… tota illa reprehensio dedecoris expressi ac saepe repetiti, non comprensisse videatur, sed erudisse luxuriam … Puto nescierant Cervulum facere, nisi illis reprehendendo monstrassem.56

… all that censure of the unseemly behaviour, [which I had] described and itemised so often, did not seem to be understood [as censure], but as instruction in self-indulgence … I think they wouldn’t have known how to do the Little Stag if I hadn’t shown them by censuring it.

This tells us almost nothing about the Little Stag, except that Pacian considered it unseemly, but that his congregation, once reminded, enjoyed it. An even more elusive, but apparently affectionate reference from St Ambrose in Milan (c. 374–97) reveals in passing that in principio anni, more vulgi, cervus allusit (‘in the beginning of the year, by folk custom, the stag frolicked about’).57

In the next couple of centuries we get a clearer picture of what cervulum facere might be. Caesarius of Arles (c. 470–542) reports that those ‘doing the Little Stag’ (cervulum facientes):

… in ferarum se velint habitus commutare. Alii vestiuntur pellibus pecudum; alii adsumunt capita bestiarum, gaudentes et exsultantes …58

… would like to change their appearance for that of wild animals. Some are dressed up in the skins of farm animals; others put on the heads of wild animals, celebrating and leaping about…

We learn too that Christians should not only not do this themselves, but ante domos vestras venire non permittatis (‘you should not let it come before your homes’).59 Clearly the Little Stag was ambulatory and this, combined with the time of year and the advice to householders, suggests a quête or good-luck visit.60

The origins of these animal disguises are unclear. The bishops associate them generally with Roman paganism, but usually because they celebrate a festival dedicated to Janus, whose double face, it was suggested, could be seen as a freakish mask.61 Some commentators have hopefully linked the cervulus with the Bronze Age Celtic stag-headed god, ‘Cernunnos’.62 The haunting figure of the animal-headed human encouraged E.K. Chambers, highly influentially, to posit an ‘unforgettable connexion with heathen cult’; while sixty years later Michel Meslin, in a largely perceptive and revealing discussion of Kalends customs, sees in this animal masking la marque la plus authentique d’une sacralité archaique.63 But there is no contemporary evidence for any active or conscoius cult, and neither the maskers themselves, nor their critics, suggest that this is the case.64 At most it may have been a traditional good-luck bringer: the stag-headed god was sometimes shown with a cornucopia or a purse of coins at his feet.65

In spite of discouragement, people seem to have stuck firmly by the Kalends Little Stag and his mates, the Heifer (iuvenca, vitula, or annicula), or the She-Goat (capra),66 well into the Christian period. Their geographical distribution is harder to map. At first the references come from around the Mediterranean: North Italy, Southern Gaul, the Iberian peninsula.67 The illusion is created that their subversive gambolling also lay in wait for churchmen and missionaries north and west into the alien heathen territory of Francia and beyond, as prohibitions on animal masking, most often based on Caesarius and Martin of Braga,68 are repeated in sermons and collections of decretals. But works like these, which were then adapted as penitentials for the use of confessors, were widely copied and compiled from each other, until it is difficult to tell if they are a reliable guide to local customs.69 However, as late as 1012 the standard compilation by Burchard of Worms prescribes thirty days’ penance for ‘doing the Little Stag’ quale pagani fecerunt et adhuc faciunt in Kalend. Januarii (‘as the heathen used to do and still do on the Kalends of January’).70

There is no firm evidence that the cervulus and his animal companions either did, or did not, frolic in Britain. It seems unlikely. Aldhelm, E.K. Chambers’ ‘only authority for the presence of the cervulus in England’, merely says in contortedly elegant, ambiguous Latin that the age when the snake and cervulus were worshipped in heathen shrines has now passed.71 There is certainly no evidence that the Little Stag, or any of its mates, is the direct ritual ancestor of such calendar customs as the Padstow ’Oss, the Mari Lwyd, or the Dorset Christmas Broad. None can be traced back to before 1800, and the hobby-horse of which they seem to be a development is recorded only from the fourteenth century.72 The only possible claim to antiquity lies with the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, and that only because the antlers carried by the dancers can be carbon-dated to the eleventh century. But the dance itself is only evidenced back to 1532, with a break at the Commonwealth and for some years after; and the reindeer antlers, according to one account, came from Scandinavia via Constantinople.73 As for Herne the Hunter, he seems to have been a mischievous creation by Shakespeare.74

There is no evidence of an unbroken tradition of popular animal masking through to the later Middle Ages. This may be because the types of record change. The Little Stag himself fades out of the written documents, either because he no longer existed or because the tradition of penitentials in which he featured came to an end.75 The great collections of canon law of the High Middle Ages seem to have given up trying to regulate popular festive behaviour, provided it did not seduce churchmen from their duties or encroach on church property.76

PLATE 1A: Staff hobby-stag. Robert de Boron Histoire du Graal (c. 1280). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fonds français 95 fol. 273r.

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris/Bridgeman Art Library.

PLATE 1B: Hobby-stag: the wearer’s face can be seen in the stag’s chest. Roman d’Alexandre. Flemish, illuminated by Jehan de Grise (1339–40). Oxford: Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264 fol. 70r.

PLATE 1C: Dance of animal maskers and unmasked women. Oxford: Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264 fol. 21v.

If he vanishes from the texts, however, the Little Stag reappears in their margins, though with no clues as to his context or status. We illustrate two cervuli from early fourteenth-century manuscripts, one French, one Flemish. Neither looks like the skirted hobby-horse of later tradition. The first shows a staff hobby-stag, the wearer’s face peering out through a hole in the chest [PLATES 1A]. It has a cheerful expression and is dancing to the bagpipes.77 The famous Bodley Romance of Alexander offers another hobby-stag, this time with two human back legs and a staff front leg, its minstrel a drummer [PLATES 1B]. It looks positively gleeful. This manuscript also contains the well-known images of strings of maskers wearing animal heads over normal clothes. One of these, combining masked men with unmasked women, suggests impromptu participation rather than formal performance; but the animal masks seem too elegantly varied to be an ad hoc piece of folk costuming, and might equally represent a courtly disguising [PLATES 1C].78 None of these illustrations seems particularly numinous, but the maskers do look as if they are enjoying themselves. In that, at least, they are true descendants of the Kalends animal maskers.

The second main disguise assumed at Kalends involved cross-dressing.79 Although it is not clear how often this involved actual face-masks, rather than, probably, a garish application of make-up, those bishops who mention it include it as a category of Kalends masking.80 Caesarius, again, provides the fullest account:

Quale et quam turpe est, quod viri nati, tunicis muliebribus vestiuntur, et turpissima demum demutatione puellaribus figuris virile robur effeminant, non erubescentes tunicis muliebribus inserere militares lacertos: barbatas facies praeferunt, et videri foeminae volunt.81

How thoroughly disgraceful it is that those who have been born men should put on women’s dresses, and by a most disgusting transformation emasculate their manly strength into the shapes of girls, not blushing to squeeze their soldiers’ muscles into women’s dresses. They exhibit bearded faces, but want to seem women.

The mention of soldiers may not just be rhetorical. On the Kalends, the Roman Army renewed its vows of loyalty to the Emperor, and received a hefty largesse.82 This was followed in some garrisons by fairly riotous military merrymaking. On the Kalends of 400, Bishop Asterius of Amaseia on the south coast of the Black Sea preached a sermon which paints a vivid picture of a Saturnalian court in which a mock-Emperor was accompanied by a harem of burly soldiers sporting ankle-length skirts, women’s sandals, wigs, distaffs, and squeaky voices.83 It looks as if this tradition had spread to the West.84 Caesarius worries that this effeminisation will sap them of their masculine strength (virilem … fortitudinem) and soldierly quality (militarem virtutem), presumably making them unfit for active service.85

Other references are less clearly military. Pseudo-Severian’s in feminas uiros vertunt (‘men turn into women’) might refer to men impersonating female deities in the official pompa.86 ‘Maximus of Turin’ (also early fifth century) likewise worries about the loss of masculine strength, but does not specify that his cross-dressers are soldiers.87 When Isidore of Seville (c.560–636) adapts Caesarius, it becomes ‘others [unspecified], perversely transformed by a female mode of behaviour, emasculate their male appearance’ (alii, femineo gestu demutati, virilem vultum effeminant).88

It is hard to tell how far this was a deliberate caricature game, how far a more seriously liminal cross-dressing. Seeing it as an army romp, some scholars tend to stress the element of parody, of male horseplay, that would emphasise the grotesque discrepancy between male body and female dress. Caesarius’ image of soldiers’ brawny limbs thrust into women’s frocks would tend to support this, as would the standard bracketing of cross-dressing with animal disguise as both ‘monstrous’ and a ridiculous ‘joke’. But the phraseology at times suggests something more than caricature. Caesarius’ sense that the men ‘wish to seem women’ chimes with Pseudo-Maximus’ claim that vir, virium suarum vigore mollito, totum se frangit in feminam, tantoque illud ambitu atque arte agit, quasi poenitat illum esse quod vir est (‘a man, by softening the vigour of his manly strength, crushes himself completely into a woman, and acts it with such a degree of make-believe and expertise that it is as if he were sorry that he is a man’).89 It may be that the female disguise could become not just a raucous and transparent guying of femininity, but a more fully-fledged attempt to lose one identity in another, and taste the freedom and strangeness of another gender.

Earlier Christian rhetoric against cross-dressing had been directed at the professional theatre. Tertullian condemns the pantomimus who plays a female role by invoking the prohibition in Deuteronomy 22: 5: cum in lege praescribit maledictum esse qui muliebribus vestietur, quid de pantomimo iudicabit, qui etiam muliebribus curvatur? (‘since [God] in the Law lays down that he who dresses in a woman’s clothes is accursed, how will He judge the pantomime who is contorted into femininity?’).90 Diatribes against both theatrical and Kalends masking were so far directed solely at male cross-dressing. But in 680 the Council of Constantinople paraphrased the text from Deuteronomy to decree more comprehensively that on public festivals nullus vir … muliebri veste induatur, vel mulier veste viro conveniente (‘no man should put on women’s clothes, nor a woman the clothes that are proper for a man’).91 This suggests that female cross-dressing was also possible, and thereafter decretals and penitentials do occasionally refer to both male and female cross-dressing at the Kalends. It is difficult to tell, however, how real this was at any given place or date.92

The third class of disguise that is occasionally mentioned is the vaguer monstra, portenta, daemones (‘monstrosities, prodigies, supernatural creatures’); vultus … quos ipsi daemones expavescunt (‘faces … at which the demons themselves are scared’).93 In this early period the generalised terms suggest an unspecified weirdness which scarcely seems a separate category, its monstrousness overlapping with the unnatural assumption of female or animal shape. It could even refer to simple black-face make-up.94 Some may have been ‘fright-masks’ of the Hallowe’en kind, portraying the malignant larvae which later gave their name to masks in general.95 Even the ‘devilishness’ is not as precise as it might seem to us today. The word daemon covered a wide range of otherworldly creatures, classified as non-Christian, but not necessarily diabolical as such.96 But as masking develops during the fully Christianised society of the High Middle Ages, ‘demons’ join animals and women as the most favoured, or at least most frequently criticised, types of disguise. The rhetoric of the preachers itself seems to have fed into the practices it condemned, the ‘monsters’ gradually becoming firmly identified as ‘devils’, and contributing to their general iconography.97

Before leaving the Kalends it is worth asking how far we can tell why people masked at the festival at all, and why in these particular forms. If this masking is not the deliberate practice of a heathen cult, what is it? The bishops condemned masking, along with all the other customs of Kalends, as a game inherited from the pagans, compromising the Christians’ new faith.98 It is clear that the Church’s main objection is not to the pagans continuing such foolish practices, but that Christians (aliqui baptizati, fratres, fideles)99 join in the Kalends masking; even worse, they seem to feel no guilt about doing so. We have no voice from the maskers themselves as to what they thought they were doing, but their bishops occasionally paraphrase or imply their defence of these games. The maskers apparently do not see their celebrations as any lingering commitment to pagan belief, but simply as good fun which can do a Christian no harm. Peter Chrysologos gives us their words:

Sed dicit aliquis, non sunt haec sacrilegiorum studia, vota sunt haec jocorum; et hoc esse novitatis laetitiam, non vetustatis errorem; esse hoc anni principium, non gentilitatis offensam.100

But one of you says, ‘This isn’t the deliberate pursuit of godlessness, these good luck visits are just for fun; this is a celebration of a new beginning, not a superstition from the past; this is just New Year, not the threat of paganism.’

This sounds much more like the attitude of most modern European Christians to their Christmas trees, or to their children’s Hallowe’en games. Whatever their subconscious motives may have been, the Kalends maskers do not appear to believe that they are involved in non-Christian worship.

Further understanding is hampered by our still scanty information about the everyday society and attitudes of the time. The connection with the New Year, with the dark restriction of winter and the transition from old to new, offers one explanation.101 Such moments of transition are frequently moments of celebration, which would account for the dominant element of play (iocus) in this masking.102 Projecting backwards from later carnival practices, we may guess that there is also an association with escape: escape from the hardship of midwinter, escape from the old into the new, escape from normal routine into riotous play, escape from duty into temporary irresponsibility, and escape from oneself into another identity. The masking may well be a playfully serious means of abandoning one’s normal self and experiencing the strangeness of the Other. Nothing could run more counter to a religion that called for vigilant sobriety and self-control.

It might, too, account for the particular disguises chosen. For a man of this period there are several obvious ways to escape, not only his normal individual self, but also his role as a human being: he can, as the preachers claim, abandon his human identity for that of an animal or monster; or he can abandon his male identity for that of the other gender. This would also link to the element of reversal, of world-upside-down, that seems appropriate to the Kalends, both as an extension of the Saturnalia and as a New Year feast.

There may, equally, be more mundane and practical reasons for the disguises. At a time when few people would be likely to own many changes of clothes, or wealth to acquire or create disguises, there are two readily accessible and highly effective means of altering identity. The clothes of the other sex are easily available; so are the skins of domestic or hunted animals like cattle and deer. Without discounting the possibly more mysterious and numinous aspects of New Year masking, we should not underestimate the real importance of such practicalities for festival customs.103

Around 1100, the Little Stag and his Kalends companions bow out from written records. The penitentials had in any case always been more interested in magical charms and fortune telling, and these are the activities which remain associated with the New Year, while concern about over-excitement and immorality switches to ‘karolles, wrastlynges, or somour games’, especially when they take place in church or churchyard.104 The Golden Legend’s reading for the Festival of the Circumcision talks of Kalends activity as something long past:

Notandum, quod olim a paganis et gentilibus in his calendis multae superstitiones observabantur, quas sancti etiam a christianis vix exstirpare poterant, quas Augustinus in quodam sermone commemorat … formas monstruosas assumebant, alii vestientes se pellibus pecudum, alii assumentes capita bestiarum, ex quo indicabatur, non tantum habitum, sed belluinum habere sensum. Alii tunicis muliebribus vestiebantur …105

It is noteworthy, that once upon a time many superstitions were observed by country folk and pagans in these Kalends, which the saints had great difficulty in uprooting even from Christians, as Augustine records in a certain sermon … they used to adopt monstrous shapes, some dressing themselves in the skins of farm animals, others putting on the heads of wild animals, from which it could be deduced that they not only had the outward appearance but also the feelings of brute beasts. Others would dress up in women’s tunics …

By 1260, then, the Kalends seem to have become history. But they resurface, at roughly the same time and with many of the same disguises, in an unexpected place: the heart of the church itself.

The Feast of Fools

It is at the end of the twelfth century in France that we first begin to hear about the Feast of Fools.106 Technically this was a special celebration for the subdeacons, the lowest of the three major orders of clergy.107 It usually took place on the Feast of the Circumcision, 1 January and was thus the direct liturgical replacement for the Kalends,108 though sometimes on Epiphany, 6 January, our ‘Twelfth Night’. However, both the term and its associated activities could shift to other clerical feasts within the Twelve Days of Christmas. In the immediate post-Christmas period, a number of saint’s days became the property of the different orders: St Stephen (26 December) for deacons, St John the Evangelist (27 December) for priests, and the Holy Innocents (28 December) for choirboys.109 The choirboys particularly seem to have seized the opportunity to join in with enthusiasm; and like other winter festivities, the whole event was intrinsically elastic, prone to overspill in both time and place.

Officially this was the feast-day when the subordinate clergy might have their symbolic moment of freedom and recognition within the church hierarchy. This clearly parallels the Saturnalian New Year impulse to reverse the social order, although it also symbolised the specifically Christian assertion that the birth of the Saviour Deposuit potentes de sede: et exaltavit humiles (‘put down the mighty from their seat and exalted the humble and meek’).110 But this formalised ceremonial reversal was very quickly supplemented by rather more inventive behaviour that pushed licence to the point of bringing the clergy into disrepute.111 In 1199, Odo Bishop of Paris issued an order reforming the Feast of the Circumcision at Notre Dame. It prohibits irregular bell-ringing, seat-swapping, songs – and masks.112 The custom was not confined to France. In 1207, Pope Innocent III condemned the wearing of monstra larvarum by Polish clergy in Gniezno.113 In 1234 his pronouncement was included in the Decretals of Gregory IX, and thus became standard canon law.114 Unavailingly: during the following centuries there was masking at Prague, Regensburg, Paris, Rouen, Soissons, Laon, Autun, and Lille, and doubtless in many other cities besides.115

Innocent III’s pronouncement provided a form of words for many subsequent condemnations of non-canonical dressing up:

… interdum ludi fiunt in eisdem ecclesiis theatrales, et non solum ad ludibriorum spectacula introducuntur in eas monstra larvarum, verum etiam in tribus anni festivitatibus, quae continue Natalem Christi sequuntur diaconi, presbyteri, ac subdiaconi, vicissim insaniae suae ludibria exercentes, per gesticulationum suarum debacchationes obscoenas in conspectu populi decus faciunt clericale vilescere …

… at times theatrical entertainments are made in these same churches, and not only are monstrosities [in the form] of terrifying apparitions [possibly ‘masks’] introduced to [produce] delusive shows,116 but also in the three feasts of the year which follow immediately after the Nativity, deacons, priests, and subdeacons in turn, indulging in demented mockery, by the unseemly intoxication of their gestures [made] in full view of the public, bring the honour of the clergy into disrepute.

It was a useful catch-all. The term ludi theatrales could be invoked equally against the riots of the Feasts of Fools and, by anti-theatrical authorities, against sober and well-intentioned liturgical drama.117 The monstra larvarum of the spectacula could apply as well to the devil character-masks (if that is the interpretation of daemonum larvas) of the 1160s play of Antichrist inveighed against by Gerhoh of Reichersberg, as to carnivalesque false faces.118 In each instance, the bishop and the offending clergy knew well enough what was going on, but we may never be certain.119

As at the Kalends, these masks appear to be only one aspect of a whole range of revels. Some of the games specifically parodied the mass: there were dances and songs in the church, puddings and sausages eaten on the altar or used as censers, buckets of water thrown at the celebrant. But the masks themselves do not sound directly parodic but rather, as the church authorities themselves sometimes observed, a residue of the popular festivities of Kalends.120 The commonest epithet is monstra: disguising as women also features occasionally.121 As part of the whole, however, they may have acquired an added dimension. The institutional and formalised ecclesiastical context of the Feast of Fools may have encouraged a more consciously subversive inversion than such behaviour outside in the streets, a closer match to Bakhtin’s theories of a carnivalesque opposition to an officially repressive culture.122 But however therapeutic it may have been to the participants, it is understandable that the authorities were worried, especially when, as they stress, all this took place in a sacred space ‘in full view of the public’. The masked monsters must have appeared far more monstrous in church;123 the mayhem they caused may have provoked hysterical laughter, but could have been threatening as well as potentially offensive to the congregation.124 We may feel inclined at this distance to smile at it indulgently as student-rag high spirits: but for those who looked on their church as a secure sacred space it could have been supremely unsettling.

In Britain, the earliest mention of the Feast itself comes from Robert Grosseteste’s episcopate in Lincoln. In (?) 1236, he forbids the profanation of the Feast of the Circumcision by the Feast of Fools, Deo odibile et daemonibus amabile (‘hateful to God and attractive to the demons’).125 A century later (1333), the clergy of Exeter Cathedral, wearing masks, were bringing themselves into disrepute by disrupting the feast of the Holy Innocents with shrieks of laughter, obscene gestures, and drunken revelry. The choirboys at Ottery St Mary, eleven miles to the East, specialised in mud-slinging during the service.126 Meanwhile over the border in Somerset, the clergy of Wells Cathedral, first in 1330/31 and then in 1337/8, were forbidden by statute to perform ludos theatrales … monstra laruarum introducentes (‘theatrical entertainments … bringing in monstrosities [in the form] of terrifying apparitions’) over the Twelve Days of Christmas.127 Wells seems thereafter to have retreated gracefully into the more decorous ceremony of the Boy Bishop. This was probably the pattern throughout the country.128

There is little evidence that in England the riotous masquerading in church overspilled into the town and became a secular event, as it seems to have done in France and the Low Countries; but one or two wisps of information suggest that it was not solely clerical. At Beverley the ‘depraving behaviour of the King of Fools’ (corruptela regis stultorum) was said to have ‘taken place inside and outside the church’ (infra ecclesiam et extra … usitata);129 it is clear that the mud-slinging choirboys of Ottery St Mary were in the habit of touring the neighbourhood for several days after the Feast;130 and there have been suggestions that ly ffolcfeste in vltimo Natali recorded at Lincoln in 1437 was a secular Feast of Fools.131 But this is nothing like the comprehensive and organised foolery which took place on the Continent. Britain lacked the particular coteries, especially the literary and dramatic ones, which took over the organisation of misrule in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.132 In the Low Countries the Chambers of Rhetoric, and in France the various ‘Abbeys of Misrule’ and other so-called societiées joyeuses produced highly sophisticated and witty dramatic fooleries, sotternien and sotties.

Perhaps, however, Chambers’ sense of a progression from the church into the town is an illusion. Recent studies of Continental material have argued that the social organisations which in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries directed secular foolery, many of them youth groups with mock kings and abbots, were already in place and active in the twelfth. The clerical Feast of Fools would then be merely a sharper because more institutionally focused version of a continuous Kalends tradition which was not recorded unless it invaded church property.133 It is certainly true that later they existed side by side: despite the prohibitions, the Feast went on in the churches while organised anarchy reigned outside. What the clerical Feast of Fools probably did was to lend an idea, a name, possibly a heightened sense of hierarchy overturned, a conscious reinterpretation of the motif of the world upside down, to seasonal revels which were in the process of expanding into full-blown Carnival.

The later, secular fools may have worn the same kind of masks and indulged in the same kind of horseplay as the clerical ones, but their presentation is different. It is probably significant that in France and the Low Countries at least, the organisers were students and men of letters. Records of the carnivalesque proceedings of the later period suggest the appropriation of a literary and dramatic tradition, which borrowed its ethos from the motif of universal folly popularised by the immense vogue of Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiffy134 and its costumes, as Brant did, from the professional fool.135 This latter may merely have added to the existing stock of carnival disguises, but the chapbooks focus on it and its ideology.

Whether any of this happened in England is debatable. Mock winter kings seem mainly to have been associated with academic or noble households, which might play sophisticatedly with the motif of foolery if it took their fancy. In England during the fifteenth century the discarded baton of the Bishop of Fools was taken up again by the Lord of Misrule. He acted as Master of Ceremonies for organised private Christmas revels.136 Fools appear in his entourage, but only in their expected capacity of court jester.137

There is some scattered evidence that there were urban Christmas Kings, especially in East Anglia: John Gladman in Norwich in 1443 may have been one of them, in which case the ‘disporte as is and ever hath ben accustomed in ony Cite or Burgh thrugh al this reame’ may merely have referred to a generalised obligation to organise appropriate entertainment for the town, or even for one’s particular circle of friends.138 In the later sixteenth and early seventeenth century it looks as if some local Lords of Misrule recreated the Feast of Fools in reverse by invading the church at Christmas during divine service and creating mayhem. At Bampton near Shap in Cumbria,

… these christemas misrule men drunke to ye minister readinge an homilie in the pulpitt … other of ye lord william [Howard’s] owne servantes came in savage manner disguised into ye churche, in ye tyme of prayer, others with shootinge of gunnes, others with flagges and banners borne … others sported them selves in ye churche with pies and puddinges, vsing them as bowles in ye churche allies, others tooke dogges counterfeitinge ye shepherdes part when he fees his shepe, and all there in ye tyme of diuine service.139

This is presumably an extreme form of the behaviour Archbishop Grindal of York envisaged in his 1570 injunction when he forbade

… anye lordes of misrule or sommerr Lordes or ladyes or anye disguised persons or others in christmasse or at may gammes … to come vnreverentlye into anye churche or chappell or churchyeard and there daunce or playe anye vnseemelye partes … in the tyme of divine service or of anye sermon.140

Our main information for the Lord of Misrule, though, comes from enclosed domestic groups large enough to want their Christmas festivities structured for them: the court, noble households, university colleges, the Inns of Court.141 These festivities may have included masking,142 but only because it belonged to the particular type of entertainment that had been scheduled for that night. We will look at the last and best documented of the court Lords of Misrule, Edward VI’s George Ferrers, in the chapter on ‘Courtly Mumming’.

Other Folk Customs

There is a handful of other folk customs in which masks seem to have been used, though it is virtually impossible to tell whether these were integral to the proceedings, or merely an adjunct to dressing up in general. One that has caused a great deal of interest is charivari, largely because in France it is recorded from the early fourteenth century, and in 1404 the Council of Langres specifically mentions that in ludo quod dicitur charevari … utuntur larvis in figura daemonum et horrenda ibidem committuntur (‘in the game which is called charevari … they make use of masks in the form of demons, and dreadful things are perpetrated there’).143

The lively and much-reproduced illustrations to the interpolated charivari episode (c.1316) in the Roman de Fauvel144 seem to show this. They are usually presented as pictures of medieval entertainers wearing masks. However, it is clear from the text that they are folk-maskers: they put their clothes on back-to-front and inside-out or wear sackcloth or monk’s cowls, smear their faces or wear false beards, play ‘rough music’, and commit a fairly comprehensive range of horrenda.145

Because in France charivari is apparently largely directed against second marriages, and because of the use of the word larva,146 nineteenth-century writers postulated that the masked figures represented the spirits of deceased first spouses which had to be propitiated by payment of a fee.147 This sounds like a rationalisation: holding the married couple up to ransom is a common form of quête in other marriage customs. In other countries, charivari can be political, or if marital, directed against wives who beat their husbands or husbands who beat their wives.148 One version can even be complimentary.149 Its essential feature is the rough music, not the masking, which appears to be incidental.

The verbal formula larvis in figura daemonum suggests that the masks were the kind that appeared in the Feast of Fools, and indeed the 1404 edict is directed against clergymen taking part in the charivari. Later, when sometimes very elaborate charivaris were undertaken by the Youth Abbeys,150 they presumably used the same masks as they did in the secular Feast of Fools. In both, however, rather than specifically representing ghosts or demons, the main intention of the masking seems to be a generalised grotesquerie and a convenient anonymity.151 On a purely pragmatic basis, the mask protects its wearer’s identity from reprisals. Worn en masse, however, as seems to have been the case in the majority of early French charivaris, it could have a more sinister effect. It detaches the animosity and censure expressed by the charivari from the individual, where one might isolate and explain them away, and makes them seem to emanate from an ineluctable communal force, antagonism made visible. Much the same effect is produced nowadays by the balaclava’d figures of sectarian demonstrations. It emphasises that this is the expression of the condemnation of the community; it also transmits a barely contained menace.

The prohibitions show anxiety about the potential for destructive violence – the gang in Fauvel broke windows and doors, and some charivaris ended by seriously injuring their victims – and the fear that they will spark off rancores et odia interdum quoque vulnerationes et homicidia (‘resentments and hatreds, and sometimes also woundings and murders’).152 ‘Charivary’, says Tom Pettitt, ‘is a malevolent encounter-custom’,153 and the masks must have reinforced this.

In England charivari does not appear to have flourished before the sixteenth century, and there is little reference to the use of masks, though one tormentor in 1618 had ‘a counterfayte beard upon his chine made of a deares tayle’.154 There is a fair amount of cross-dressing and wearing of horns, a more likely source for Falstaff’s disguise in The Merry Wives of Windsor than any fancied pagan-god figure,155 and effigies are also popular. Much of this is to provide a surrogate for the victim(s). No matter how much the participants may have thought themselves justified in censuring those who had broken the implicit rules of society, this is masking as aggression, a dark note in the spectrum of generally festive, if potentially dangerous, communal play.

Another previously unrecorded continental custom, which introduced a new masking figure, was the Wild Man hunt. This enigmatic being may be a genuine seasonal folk-figure; in Italy he eventually became a feature of the winter Carnival, though the earliest record of a ludus de homine salvatico, at Padua in 1208, was, confusingly, in high summer.156 The Wild Man of the Woods had a rich literary and artistic existence from the twelfth century,157 and it is difficult to tell whether his appearance in this form was a new creation, or a re-reading of an earlier folk-masking figure, such as the Bear with whom he is often associated or conflated.158 Both were dressed in furs, or fur-lined garments turned inside-out;159 though sometimes the ‘Bear’ is a creature dressed in straw,160 and the Wild Man in leaves, moss, or even lichen.161 A Northern version was the schoduvel, ‘terrifying devil’, of the Hanseatic towns. Dressed in fur, it ran and leaped: at Christmas 1478 one was killed by a beer-mug aimed by a terrorised spectator.162 It is possible that they, like the Austrian Perchten, originally represented malevolent wood-spirits who were believed to haunt the countryside in winter, and must be driven away.163 In folk customs recorded from the nineteenth century, the Wild Man/Bear is hunted and eventually killed. His death is said to bring the end of winter.164 The medieval ludus may also have ended this way: a so-called ‘Play of the Death of the Wild Man’165 is featured in Bruegel’s painting of Carnival and Lent.

Boccaccio uses the Wild Man hunt as a setting for his story of the punishment of the philandering Frate Alberto in the Decameron. The friar is told by a wronged citizen with whom he has unwittingly taken refuge:

Noi facciamo oggi una festa, nella quale chi mena uno uomo vestito a modo d’orso, e chi a guisa d’uom salvatico, e chi d’una cosa e chi d’un’altra, e in su la piazza di San Marco si fa una caccia, la qual fornita, è finita la festa.166

Today we are holding a fiesta, to which everyone brings someone dressed up as a bear, or as a wild man, and some as one thing and some another, and then there will be a hunt in the Piazza San Marco, as the culmination of the fiesta.

He dresses the Friar as a wild man, in feathers stuck on with honey, masks him, and leads him to the Piazza where he is stung by bees and gnats, exposed, and beaten by an uproarious crowd. In this tale, the wild-man costume marks Alberto out as a being of unbridled lusts who must be driven out of civilised society and symbolically killed, possibly Boccaccio’s consciously literary take on the original folk-creature.167 The story is not conclusive evidence of a Wild Man hunt at Venice in the 1340s,168 but it clearly expects its readers to recognise the game.

There is no evidence of a fully-fledged Wild Man hunt in England, but the strong cultural symbolism of the wild man made him a popular figure in all kinds of festivity, from courtly disguisings, where playing in character licensed usually impermissible ‘uncivilised’ behaviour,169 to civic parades like the London Lord Mayor’s Show, in summer as well as winter. His larger-than-life physique could be exaggerated into the typical pageant giant, and his threatening demeanour made him an ideal stitler, clearing the way with his club and squib, a firework hidden in a bunch of greenery.170 The liberating mask and the release from normal social restraints could paradoxically be harnessed as an instrument of crowd control.

A few other enigmatic references to masking provide snapshots which may have been sui generis or which may hint at a whole submerged world of folk practice. Why, for example, should any member of the Palmers’ Guild of Ludlow wish to attend a wake wearing a mask? An ordinance, copied out some century after its supposed date of 1284, states that a brother is allowed to attend a wake provided:

… nec monstra larvarum inducere [sic], nec corporis vel fame sue ludibria nec ludos alios inhonestos, presumat aliqualiter attemptare.171

… that he does not presume in any way … either to put on [lit. lead in] monstrosities in the form of terrifying apparitions [probably ‘masks’], nor embark on mockery(?) of his [the dead person’s?] body or reputation, nor any other unseemly games.

This seems to be a garbled version of the common decretal about holding riotous celebrations at wakes, ‘as if you seemed to rejoice in your brother’s death’ (quasi de fraterna morte exsultare visus es),172 which might explain the concept of mockery of the deceased’s body or reputation; but the role of the masks in this is unclear. It seems to have been tinged verbally with the Feast of Fools prohibition, and one might dismiss it as such, if it were not that a decretal in Burchard of Worms’ collection also suggests that the wearing of larvae could be a feature of gatherings in commemoration of the dead. Parish priests are admonished, when attending such events, not to get drunk:

… nec plausus et risus inconditos, et fabulas inanes ibi referre, aut cantare præsumat, vel turpia joca, vel urso, vel tornatricibus ante se facere permittat, nec larvas dæmonum, quas vulgo Talamascas dicunt, ibi ante se ferri consentiat: quia hoc diabolicum est, et a sacris canonibus prohibitum.173

… nor to [indulge in] applause or unseemly laughter, nor to relate foolish tales, or offer to sing, or to allow coarse entertainments, either by a bear or by female tumblers,174 to be performed before him, nor allow frightening apparitions of demons which are called Talamascas in the vernacular,175 to be carried [worn?] there before him: because this is devilish, and prohibited by the sacred canons.

This appears to go back as far as Hincmar’s collection of synodical decrees, dated 852.176 The syntax does not make it entirely clear whether all these were expected features of a ninth-century funeral party, or more generally of any event to which a parish priest might be invited; and the bear and the female tumblers seem to rob the masking of some of its otherworldly resonances. What relationship it might have to something happening four hundred years later in the Welsh Marches is equally obscure. The exact details of what was going on in Ludlow, or why, remain a mystery.

Notes

1 Joseph Bosworth and T. Northcote Toller An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (London: Oxford University Press, 1898) and Supplement (1921) svv. grīma, grīm-helm, beado-grīma, here-grīma.

2 Sometimes simply grīma as in Beowulf line 334; sometimes compounded, as here-grīma, ‘warband-mask’ in lines 396 and 2605; or beado-grīma ‘battle-mask’, as in 2257.

3 The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial Volume 2: Arms, Armour and Regalia edited Rupert Bruce-Mitford (London: British Museum Publications, 1978) chapter 3, ‘The Helmet’, especially pages 185–225. For links with Beowulf, see G.N. Garmonsway, Jacqueline Simpson and Hilda Ellis Davidson ‘Beowulf’ and its Analogues (London: Dent, 1968) 350–60.

4 Bruce-Mitford Sutton Hoo 220–24 and figure 169 which shows two surviving Roman cavalry helmets with face masks, apparently used for display manoeuvres. One is from Ribchester, Lancashire. Another two are in the National Museum of Scotland: see J. Curle A Roman Frontier Post and its People: the Fort of Newstead in the Parish of Melrose 2 vols (Glasgow: J. Maclehose, 1911) 1: 168–73 and plates 29 and 30. He quotes Arrian on the use of such masked helmets in cavalry sports. See also J. Garbsch Römische Paraderüstungen (Munich: Beck, 1978) 4–7, 69, and plates 12–27; L.J.F. Keppie and B.J. Arnold Scotland (Corpus signorum Imperii Romani 1:4; Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1984). The Roman examples are naturalistic, unlike the Anglo-Saxon version, though one represents an Amazon.

5 Bruce-Mitford Sutton Hoo 208–20. Others have spectacle-like eye protection, a nasal, and cheek guards: some a curtain of chain mail hanging from the bottom.

6 The Sutton Hoo helmet might, like the Roman parade helmets, have been used for purely ceremonial purposes. As reconstructed, it shows no signs of having been in a battle: but Anglo-Saxon literature suggests that they were intended as combat gear.

7 Beowulf 303–5: there is a boar image on the crest of the Benty Grange helmet, and two small boar’s heads at the ends of the eyebrows of the Sutton Hoo helmet. The boar is said to have been sacred to the god Freyr.

8 For the York Coppergate helmet (late eighth century) discovered in 1982, see Dominic Tweddle The Coppergate Helmet (York Archaeological Trust, 1984).

9 Like the Germanic term masca, which does not however turn up in Anglo-Saxon: see chapter 13 on ‘Terminology’ 338–9.

10 Eric Partridge Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1958) sv. grim; Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary and Supplement svv. grīma, grimm, gram. For further discussion, see chapter 13 on ‘Terminology’ 340.

11 Their horned helmets have the same crest but are a different shape on the forehead from the other examples, which resemble a Bronze-Age pair now in the National Museum of Copenhagen. These are not visored, and merely cover the top of the skull: but they have what appears to be a stylised bird’s beak and two protruding round eyes. See Hilda Ellis Davidson Scandinavian Mythology (London: Hamlyn, 1969) 21 for illustration.

12 See The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture AD 600–900 edited Leslie Webster and Janet Backhouse (London: British Museum, 1991) 22 and figure 2 for the Finglesham buckle; see, among others, Gale R. Owen Rites and Religions of the Anglo-Saxons (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1971) 14–15, and plate 2.

13 Bruce-Mitford Sutton Hoo 186–9, 206–9, and figure 156. He remarks that ‘The two men, although carrying sword and spears, seem to be dressed in civilian or ceremonial dress, and not in war gear’ (187). See also A. Margaret Arendt ‘The Heroic Pattern: Old Germanic Helmets, Beowulf, and Grettis saga’ in Old Norse Literature and Mythology: a Symposium edited Edgar C. Polomé (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1969) 130–99; Davidson Scandinavian Mythology 49.

14 Chambers Mediaeval Stage 1: 203.

15 Tacitus De origine et situ Germanorum (‘Germania’) edited J.G.C. Anderson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1938) 24. The editor (126–7) suggests that it is a dance in honour of the war-god Tiu, but Tacitus himself sees it purely as a pastime showing bravery and dexterity. Arendt, who relates the dance to the Torslunda dies, sees it as ‘a ritualistic initiation consisting of a kind of mock death and reawakening’ (138–9) apparently extrapolating backwards from the mummers’ play, or from its supposed connection with the cult of Woden/Óðinn. None of this is confirmed by Tacitus, and it seems to have happened on a regular basis, not as a rite de passage.

16 Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos (AD 912–59) De cerimoniis aulae byzantinae 2: chapter 92 (83); see Le Livre des céremonies edited and translated Albert Vogt (Paris: Les Belles lettres, 1935–40); also Averil Cameron ‘The Construction of Court Ritual: the Byzantine Book of Ceremonies’ in Rituals of Royalty edited David Cannadine and Simon Price (Cambridge University Press, 1987) 106–36.

17 The Silver Latin poets usually characterised Germanic barbarians and especially the Goths as wearing skins: see e.g. Claudian De bello Gothico 481–2, In Rufinum 2: 79–83; Rutilius Namatianus De redito suo 2: 49, in Minor Latin Poets edited and translated J.W. Duff and A.M. Duff (Loeb; London: Heinemann, 1934).

18 Stringed instruments like a long-necked lute.

19 If they were Goths and not, as their latest editor believes, Byzantines in costume wearing ‘Gothic’ character masks: Livre des céremonies 4: 186. The song has been quoted as invoking the names of Germanic deities as well as that of Christ, but Vogt dismisses this as fantasising.

20 See entry on ‘Berserkr’ in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopaedia edited Phillip Pulsiano (New York and London: Garland, 1993); E.O.G Turville-Petre Myth and Religion of the North (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964) 61; Hilda Ellis Davidson The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe (London: Routledge, 1993) 99–100. Arendt ‘Old Germanic Helmets’ illustrates two other versions of this creature in her plates 17 and 18. Another strange hybrid creature appears on the Franks Casket, but it seems to be a female, possibly from a shape-changing narrative: see The Making of England 101–3.

21 Plutarch’s Lives translated ‘Bernadotte Perrin, 11 vols (Loeb; London: Heinemann, 1920) 11: 532–3.

22 Plutarch’s Lives 514–15.

23 Olaus Magnus Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus introduced John Granlund (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1972, facsimile reprint of Rome: 1555) book 15, chapter 23. The woodcut which accompanies the description, designed by Olaus himself, does not suggest masking.

24 See Davidson Lost Beliefs 144–59 for an account of fashions in this branch of scholarship.

25 See for a balanced counter-view Ronald Hutton The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (Oxford: Blackwells, 1991), especially 295–8, and at intervals in his later The Stations of the Sun: a History of the Ritual Year in Britain (Oxford University Press, 1996).

26 See for example the entries on ‘Óðinn’ and ‘Religion, Pagan Scandinavian’ in Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopaedia; Davidson Lost Beliefs 77. On ‘Woden and Witchcraft’, see Richard North Heathen Gods in Old English Literature (Cambridge University Press, 1997) chapter 4.

27 In the Grímnismal Óðinn goes in disguise to the hall of King Geirrod, calling himself Grímnir, and ‘would say nothing more about himself although he was asked’. Geirrod tortures him: he eventually reveals himself by listing his names. See The Poetic Edda translated Carolyne Larrington (Oxford University Press, 1996) 50–61, verses 46, 49; for original, see Edda: die Lieder des Codex Regius Vol. 1 edited Hans Kuhn (Heidelberg: Winter, 1962) 66–7. See also Davidson Lost Beliefs 42, 60; Turville-Petre Myth and Religion of the North 61–2. It is a temptation to link this with mumming visits (see chapter 4 on ‘Mumming’), but the ‘stranger in disguise’ motif is too common to base a theory on.

28 This is an exaggeration, but only just. Prudence Jones and Nigel Penninck, in a serious attempt at a scholarly survey, say almost exactly the same thing: A History of Pagan Europe (London: Routledge, 1995) 154–9 under the heading ‘Northern Martial Arts’.

29 See John Emigh Masked Performance (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996) passim.

30 It is much easier to prove that something happened than that it did not. See, for examples of heathen practices, Arthur W. Haddan and William Stubbs Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents relating to Great Britain and Ireland 3 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1871, reprinted 1964) 3: 188–90, 235, 420–24, 458–9. None of this, except possibly ritual scarring of the face (458), seems germane to this investigation. For Laws, see Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen edited F. Liebermann, 3 vols (Halle: Niemeyer, 1903) 1: 13, 38–9, 128, 130, 134, 152, 236–7, 244, 246, 254, 310, 383; the same is true of them. The clearest definition of the Anglo-Saxon view of pagan practices is in the Laws of Cnut drawn up by Wulfstan, Archbishop of York c. AD 1020. Dorothy Whitelock conveniently translates a selection from the Laws in English Historical Documents 1: c. 500–1042 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1955) 357–439.

31 On Anglo-Saxon penitentials and their interrelations, see Allen J. Frantzen The Literature of Penance in Anglo-Saxon England (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1983). On penitentials in general, see John T. McNeill and Helena M. Gamer Medieval Handbooks of Penance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1938).

32 On continental decretals and the questions they raise, see below 30, and 36 note 91.

33 In any case, evidence about the native importance of the winter solstice celebrations is conflicting. See Bede De temporum ratione: PL 90: 356; Ælfric De Sancta Trinitate et de festis diebus line 75, in Homilies of Ælfric: A Supplementary Collection edited J.C. Pope, EETS 259 (1967) 466–7); and note 35 below.

34 Haddan and Stubbs 424. This comes in a section De auguriis vel divinationibus, and is immediately preceded by a prohibition against honouring Thursday for the sake of Jupiter: both come straight from Caesarius of Arles (see below 27 note 48). McNeill and Gamer Medieval Handbooks discuss its authenticity on pages 237–8. Egbert was a pupil of Bede.

35 According to Bede (De temporum ratione: PL 90: 356), the pagan Anglo-Saxon year was divided at the equinoxes into winter and summer: winter began with full moon in October. Géol (‘Yule’) was merely the two-month period we now call January and February. However, he also says that the year begins on the day ‘when we now celebrate the birth of the Lord’ (ubi nunc natale Domini celebramus) at a feast called Modranicht, ‘Mothers’ night’. Ælhic objects to a popular idea that the year begins on 1 January, since the Creation of the world took place on 21 March: Sermon on Octabas et Circumcisio Domini lines 129–30, in Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies: The First Series edited Peter Clemoes EETS SS 17 (1997) 228–9. He says that foolish people perform many charms on that day to promote long life and good health, but not what they are, though one can find examples in some penitentials (none of them involve masking). It does not sound, however, as if this were a particularly significant pagan Anglo-Saxon festival, and he may be imitating continental sermons which refer to the Kalends. But by this time, and from the earliest Laws, the important celebration is the Twelve Days of Christmas, which was a public holiday.

36 Wiliam Prynne Histriomastix preface by Arthur Freeman (New York and London: Garland, 1974: facsimile reprint of London: Michael Sparke, 1633) 757.

37 The earliest evidence for masking associated with the Saturnalia is an illustration in the Codex Calendar manuscript of AD 354. Seventeenth-century copies of this now lost manuscript (illustrated by a Christian and presented to the Christian aristocrat Valentinus) show a picture for December, illustrating the Saturnalia, which includes what appears to be a full-head theatre mask. This would suggest taking part in the pompa circensis (see below) rather than casual private masking. See H. Stern Le Calendrier de 354: étude sur son texte et sur ses illustrations (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1953) 283–6; M.R. Saltzman On Roman Time: the Codex’Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990) 74–6. Macrobius, however, claims that the Saturnalia came to merge with the Sigillaria, when infants were amused with oscillis fictilibus (‘little masks of clay’): Saturnalia edited Jacob Willis (Leipzig: Teubner, 1970) 43; translated P.V. Davies (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1969) 74: but these seem to have been more like nursery mobiles than actual masks: an oscillum is ‘something that swings’.

38 For fuller information see H. Scullard Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (London: Thames and Hudson, 1981) 74–5; Religions of Rome edited Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price, 2 vols (Cambridge University Press, 1998) 2: 124–6.

39 … mensem Decembrem fuisse, nunc annum (‘December used only to be a month long: now it seems to go on for a year’): Seneca Ad Lucilium epistolae morales edited R.M. Gummere (Loeb; London: Heinemann, 1917) Epistle 18, page 116.

40 For the themes of the festival see H.S. Vernel Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman Religion Volume 2: Transition and Reversal in Myth and Ritual (Leiden: Brill, 1994) 146–227.

41 Here in a Latin translation by Erasmus that became a standard sixteenth-century schoolboy text: Luciani dialogi varii: Saturnalia translated Desiderius Erasmus (Paris: Badius, 1506) in Opera omnia Desiderii Erasmi Volume 1 (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co., 1969) 382. Although in terms of masks the soot-blackened faces may sound promising, the context suggests blindfolded games rather than fully-fledged masking, the kind of game where the unwitting victim is daubed with soot or flour, as Wit is in John Redford’s Wit and Science (in Tudor Interludes edited Peter Happé (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 181–219): see chapter 10 on ‘Morality Plays’ 272–5.

42 ‘The realms of Saturn’ or the Golden Age: Virgil Eclogues 4: 6. In medieval astrology, the planet Saturn ruled over the zodiacal sign Capricorn, which included the Kalends.

43 See Michel Meslin La Fête des kalendes de Janvier dans l’empire romain (Collection Latomus 115; Brussels: Latomus, 1970). Ovid gives a full account of the festival and its traditional origins in Fasti 1: 63–294: Ovid Libri fastorum edited E.H. Alton, D.E.W. Wormell and E. Courtney (Leipzig: Teubner, 1988).

44 This became an accepted part of the Roman patronage system, a form of corporate gift-giving in reverse. Gifts were handed up the chain from patron to patron; the biggest presents went to the Emperor, who also received a formal visitation of the vota exchanged more casually among friends and acquaintances.

45 Ovid explains the significance of the midwinter moment as marking the rebirth of the Sun (Fasti 1: 63–4), although he points out that it would be easier to imagine this in the Spring (Fasti 1: 149–60. But there was no official acknowledgement of Sun-worship.

46 See comments on the length of Saturnalia in Macrobius Saturnalia edited Willis, 39–43, book 1, chapter 10; translated Davies 70–73.

47 Homily attributed (probably wrongly) to Maximus of Turin (c. 412–65) Homilia XVI: de calendis Ianuarii, PL 58: 255. A broad range of comment by the Early Fathers on Kalends customs is usefully brought together in Chambers Mediaeval Stage 2: 290–306. Taken out of context, however, these comments can be misleading: they seem more homogeneous than in fact they are.