Christianos certis diebus bacchari et furere, donec genere quodam cineris in Templo respersi, redirent ad se, et convalescerunt.

For several days the Christians rave and go crazy, until sprinkled with some kind of ash in the Temple they come to themselves and recover.

(Observation on Carnival attributed variously to the envoys of Prester John and Suleiman II)1

Carnival, throughout most of Europe, was the most striking and spectacular of the late-medieval masking traditions. Yet masking was only one element in a winter playtime that spread right across countries and classes, sometimes for weeks at a time. In the medieval Christian calendar it was the festival to celebrate and bid farewell to plenty immediately before the privations of Lent. But the accepted carnival period frequently spread backwards from the climax of the jours gras, the Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday before Ash Wednesday. The earliest date on which Shrove Tuesday can fall is 3 February, the day after Candlemas, which marked the end of winter and, as the final festival of the childhood of Christ, seems also to have closed the Christmas festivities.2 The temptation to merge with the Twelve Days of Christmas and New Year celebrations proved strong, at least in Mediterranean countries. By the end of the sixteenth century we are told of ‘the tyme of Carnavall from Christmas feast to Ashwensday’3 – the entire period between the two major fasts of Advent and Lent.

Late-medieval Carnival was thus not the warm midsummer festivity we now associate with Rio de Janeiro or Notting Hill.4 Its play is a sometimes fevered response to the season of short days, long darkness, cold, and, for many, enforced inactivity. Perhaps this, as much as the Christian prospect of Lenten privation, contributed to the association of Carnival with licence. The quotation opening this chapter, an anecdote often repeated by both attackers and defenders of the festival, spells out the perceived correlation of Carnival with madness. Not only uncomprehending foreigners, but local commentators constantly associate Carnival with insanire, furire, bacchari (‘going mad, raging, raving’).5

It seems to have been recognised as a time for escape, for letting go the restraints of rationality, social hierarchy, and self-control. Its games include excessive eating (especially pancakes and sausages: greasy calorie-packed ‘fast food’); playful or comic aggression and competition in races, football games, cockfights, egg-, snowball-, and orange-battles; alternative power-structures, with mock kings, reynages, and Lords of Misrule; and liberation of the imagination in fantastic spectacles and exotic masquerades, as well as more informal free play.6 Some of these are in the Kalends tradition; some are a direct response to the chill of winter and the need to release pent-up energy.

Given such a complex and multi-faceted phenomenon, it is dangerous to oversimplify any of its meanings. Carnival is not just liberation and anarchy; it is clear that a lot of carnival play was quite tightly structured. Apart from the highly organised public spectacles seen in many places, even informal festivity tended closely to follow traditional local custom. You did not do just anything, but joined in conventionalised and agreed forms of liberation. Along with its other paradoxes Carnival always seems to show this mixture, at times a tension, between licence and control, spontaneity and structure.7

In many countries, at many times, many of these different activities took place in masks. Judging from the records, carnival masking seems to be an extension of the popular mumming house-visit, the élite masked ball,8 and possibly the seasonal disguising as animals or wild men we saw in the previous chapter. At one fairly obvious level, it forms part of the general liberation. A mask can give freedom to be other than yourself, to do and be things which your community, and you yourself, would not normally expect or tolerate.

Earlier historians over-enthusiastically saw Carnival as a tradition which went back time out of mind, a genuinely popular outpouring of exuberance, even a direct descendant of the pagan Kalends.9 But much of the evidence for this evaporates on examination. The name itself, in its Latin forms of camelevale, carnelevarium, is recorded from the twelfth century, but in context means only ‘the Sunday before Lent’, or later, ‘Shrove Tuesday’.10 Its antiquity has been argued by quoting the condemnations of Kalends masking by Caesarius and his fellow bishops, or the decretals against the Feast of Fools: both at that stage connected with New Year, not the run-up to Lent. Other historians seized on early evidence of particular calendar customs, such as the castle-smashing or the caccia in Venice,11 or the schoduvel (‘frightening devil’) in Germany, and assume that this implies the existence of the full blown Carnival in which they are later embedded.

The evidence needs reviewing thoroughly: but it is possible that Carnival as we think of it was largely an urban fifteenth-century invention, promoted by the local élite, whether aristocratic, mercantile, or guild, or in the case of Rome, ecclesiastical, who took the lead in providing entertainments and shows in which the popolani were invited to act either as audience or as participants. This regularised and licensed activities like mumming or the savage street battles beloved of the Venetians and Florentines,12 and absorbed the more official pre-existing calendar customs. The exact nature of the proceedings would depend on the social structures, and relative prosperity, of each town. And it was, to begin with, a Southern European phenomenon.

This might explain why Carnival as such never reached England. Although many of the popular activities subsumed under Carnival – mock kings and masked house-visits, football games and feastings – can be found here and there through the island from Christmas celebrations up to Shrove Tuesday, there is very little sign of that climax of communal, masked street festivity around the few days preceding Ash Wednesday that was so characteristic of mainland Europe. Carnival as a distinct and separate phenomenon does not seem to have crossed the Channel.

Since this is so, why are we devoting a chapter to it? Partly because it demonstrates various aspects of masks and masking behaviour in their most intense form. We can extrapolate, with caution, when we try to assess parallel English customs. By the sixteenth century, too, authors and playwrights in England were aware of its existence, and some of its customs did percolate through to this country. Also at that time, we find an unusually rich vein of contemporary comment, from sophisticated and self-conscious analysis by Italian writers like Tasso and Castiglione, to rather more naive observations by tourists like Sastrow and the brothers Platter.

Medieval and early-modern Carnival has recently attracted a widely influential body of comment and discussion. This has frequently moved beyond the activity itself to generate conceptual frameworks for use elsewhere in literary, political, or sociological interpretation: not so much Carnival as the carnivalesque.13 We cannot help reacting to this theoretical analysis. Our main purpose, however, is not to contribute to the ongoing debate, but to look at the role of masks and masking in the festival itself.

Carnival in Southern Europe

Medieval Carnival may have originated in Italy. Certainly in the late Middle Ages, Italy was the Carnival King of Europe, where carnival customs seem most widespread, flamboyant, and developed. These were widely shared by Spain and southern France, and it is from these areas that we can draw some broader conclusions about the masking traditions of late-medieval Carnival.

Even for contemporary observers, the meaning of Italian Carnival clearly depended on point of view. A Protestant English traveller to Rome in the later sixteenth century, plainly unaccustomed to such festivity, dismissed it as no more than:

… a very great coyle, which they use to call the Carnevale … so great is the noyse and hurlie burlie … it is unpossible for me to tell all the knaverie used about this.14

Torquato Tasso, on the other hand, a sophisticated Italian participant, writes at the same moment of Carnival in Ferrara:

… e mi parve che tutta la città fosse una maravigliosa e non più veduta scena dipinta, e luminosa e piena di mille forme e di mille apparenze, e l’azioni di quel tempo simili a quelle che son rappresentate ne’ teatri con varie lingue e con vari interlocutori.15

… and it seemed to me that the whole city had become a wonderful and unique painted scene, radiant and full of a thousand forms and a thousand appearances, and what was being done at the time was like what is represented in a theatre, with different voices and different characters.

Late as they are, these comments illustrate vividly the difficulty for us of pinning down the experience of late-medieval Carnival. Even at the time it might seem either chaos, or paradisial illusion; though both observers perhaps agree on the sensation of being in a heightened world different from everyday normality.

The time this world occupied was both elastic and specific. Although peaking in the few days preceding Ash Wednesday, it might in different cities start at any time from 1 January onwards. Carnival time was sometimes formally decreed: in fifteenth-century Ferrara the start of the masking season was personally licensed by the Duke. Public masking at other times of year was a criminal offence.16 Rome imposed a curfew, banning street masking after 2 a.m. in the carnival time.17

Place was similarly significant but imprecise. The evidence from Italy and Spain suggests that Carnival was chiefly an urban, rather than a rural festival. Its games and maskings seem to belong to communities which are large, mixed, and crowded enough to make the freedom of masked anonymity (or quasi-anonymity) important, and the chance of both group activity and random anonymous encounters important. Carnival games belonged not only to cities but largely to the streets. There were certainly domestic celebrations, especially in the courts and large houses: masked balls, plays, and feasts.18 But masking through the streets, often in the dark, in bad weather, among crowds of known and unknown others, is one of the most powerful motifs of European late-medieval Carnival.

Masking Activities

Masking activity should be seen in the context of a whole range of carnival play. Ad hoc participatory fun was combined with organised games and shows, masked and unmasked, initiated and arranged by the authorities. Rome enjoyed a series of races run through the city streets on consecutive days by Jews, old men, young men, boys, asses, buffaloes, horses, and mares. Venice presented a public hunt and slaughter of bulls and pigs in the Piazzetta, where the Senators smashed a series of miniature wooden castles. Florence was renowned for elaborate and spectacular cavalcades, thematic allegorical processions, and songs.19

It is hard at this distance to judge whether any of these shows offered what is now thought of as a ‘carnivalesque’ mix of official spectacle with its popular or grotesque inversion. The Roman races, for example, mingle contests between young men or horses with potentially parodic versions by Jews or old men. In the 1580s the English visitor Munday sees the Jews as parodic victims, harassed and goaded as they ran,20 but earlier local records of the races perceive no such overt discrimination. According to John Burchard, papal master of ceremonies 1483–1506, the Pope himself displayed the prizes for the various races with equal ceremony.21 The butchery and castle-smashing of Venice might equally seem to present the ludicrous comic violence often associated with Carnival; yet contemporary accounts are ambivalent, sometimes presenting the ceremonies as serious historical pageants, at other times as undignified and unworthy concessions to popular taste.22 There is scope, but no firm support, for twentieth-century ideas of the ‘carnivalesque’.

Alongside the civic displays came the informal carnival celebration of the city people. Most frequently this took the form of masking through the streets, singly or in groups, on foot or horseback, often until late in the night. Another common motif was the throwing of snowballs or eggs. Eggs, sometimes filled with perfumed waters, were often thrown at the watching women, especially courtesans, in the upper windows.23 They retaliated with eggs and less delightful things: repeated edicts prohibit the throwing of rubbish, dead cats, and other scorzezze (‘nastinesses’) from the windows.24 Full-scale battles with eggs, snowballs, or oranges might take place in the piazze. One famous egg fight in Ferrara in 1478, in which Duke Ercole himself took part, lasted for an hour e tuti quelli se ritrovòno in Piaza, forno caregi de ove rotte (‘and all who found themselves in the Piazza contested with rotten eggs’).25 Such informal play was probably the major business of Carnival, although the civic and organised shows are inevitably better recorded.

Carnival Masks

Masking seems to have been frequent in official spectacle and central to the informal games. But what kinds of face-coverings were these? Where organised shows involved masks it was most often in the form of masked processions, usually made up of thematic groups. Carnival songs from Florence present groups as diverse as Amazons and Venetian fishermen, Magnificos, wet nurses, and wildmen. We hear of similar, though more informal groups in Avignon and Marseilles.26 Burchard in Rome in 1502 describes a parade of:

… triginta mascherati habentos nasos longos et grossos in formam priaporum sive membrorum virilium in magna quantitate.27

… thirty maskers with great long noses like priapuses or penises of an enormous size.

The startlingly successful carnival floats Piero di Cosimo designed for Florence also featured such thematic and fantastic masks. The Triumph of Death in 1511 involved:

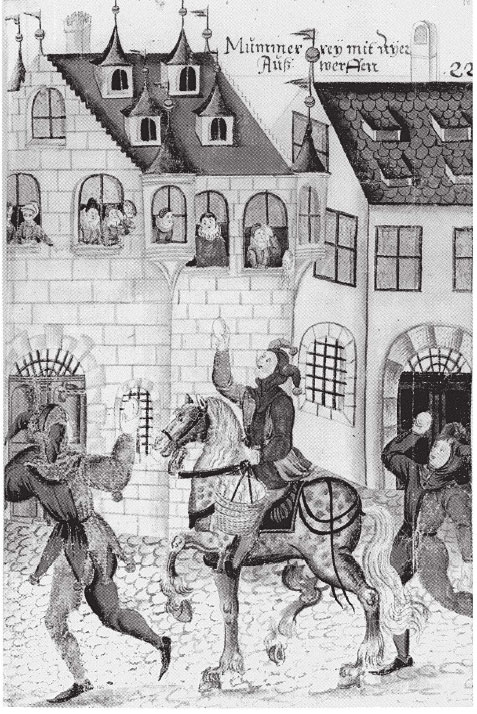

PLATE 2: Schembart carnival maskers throwing eggs at female spectators. Schembartbuch: Nuremberg, Hans Ammon [? 1640]. Oxford: Bodleian Library, MS Douce 364 fol. 183r.

© Reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

… maschere che pigliavano col teschio di morto il dinanzi e ’l dirieto e parimente la gola, oltra al parere cosa naturalissima, era orribile espaventosa a vedere.28

… masks painted behind and before like skulls, including the throat, most realistic but a horrid and terrifying sight.

An element of wonder, of fantastic artistry, was often important, then, in organised maskings. What of the masks worn by individuals in the more impromptu street-festivity? If the sole purpose were anonymity, then a bag over the head would have sufficed. Yet it is clear that many masks were made and designed with great care, elaborate and often delicately characterised. Particular centres developed for mask-making, in Modena, Ferrara, and Bologna, and the mask became an art-form evoking wonder and artistic glamour.29 In 1498 Cardinal d’Este at Milan requested 400 masks from Ferrara, while the Ferrarese ambassador presented another 200 to honour the marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots to the French Dauphin in 1558.30

Apart from character and type masks, grotesque and beautiful faces, and devils, there were birds and animals. A sixteenth-century mask-makers’ carnival song refers, among others, to owls and crows.31 The very fantasy and randomness of these carnival masks tends to undermine any idea of deliberate impersonation. More important, it seems, was to cease to be yourself, so that the mask let you behave in different ways, rather than imposing its own character upon you. There seems little evidence of masqueraders celebrating wholly ‘in character’.

Carnival Maskers

The large numbers of masks bought and sold confirm the communal quality of carnival masking. This was not a tradition in which a few maskers are observed by a larger number of unmasked faces. Munday reports that, ‘During this time, every one weareth a disguised visor on his face, so that no one knowes what or whence they be’.32 The Florentine mask-makers’ song claims that quasi ognun se le mette (‘almost everyone puts them on’). The prologue to a carnival comedy tells the audience that at carnival time la /Maggior parte degli uomini, e fors’anco / Delle donne, o e’vanno, o e’desiderano / … di andare attorno in maschera (‘Most men and perhaps also women, either are going or want to go around in masks’).33 While it seems unlikely that everyone masked, the participation of diverse elements of the community probably contributed significantly to the experience of Carnival.

It is clear, for example, that carnival masking did not belong solely, or even chiefly, either to the popolani or to the aristocracy or authorities. Either end of the spectrum might at times dominate or appropriate it. Young aristocrats sponsored the carnival shows in Florence, and Duke Ercole masked with flamboyant enthusiasm at Ferrara; yet public order regulations and the comic stories of popular masking in Rome and Venice suggest that masking was equally an important and expressive province of ordinary citizens. The notion of separate and opposing cultures, élite versus popular, is not borne out by the evidence. Rather, as Gurevich and others have suggested, we find an interaction, at times a deliberate blurring of social categories, even if it is one in which élite groups had more freedom of cultural movement than ordinary people.34

The relations between the authorities – princes, senators, governors – and the popolani over masking may cast some light on the wider purposes of Carnival. Structured public activities were, predictably, generally organised by those in charge. In Venice, the Doge and Senators financed the animal fights and participated in the castle-smashing; in Rome the Pope presented the prizes for the carnival races: but ordinary citizens were frequently involved, as competitors in the Roman races or processing as trade bands in Florence. More striking, perhaps, is the energy with which the authorities joined in the informal masking games. The most notorious is probably Duke Ercole in Ferrara, the moving spirit in street masking, erotic encounters, and egg-fights. Burchard’s phallic maskers ostenderunt se pape qui erat in fenestra supra portam (‘showed themselves to the Pope who was at the window over the gate’), and the Cardinals not only watched but masked themselves:

His diebus, ut vulgo dicebatur, cardinales Sancti Georgii, Parmensis, Columna et Ascanius pluries equitarunt larvati, aliquando omnes simul, aliquando alius cum alio.35

In these days, as was commonly reported, the Cardinals of St George, Parma, Colonna, and Ascanio rode several times masked, sometimes all together, and sometimes in pairs.

A more hostile sixteenth-century English account claimed that the Cardinals’ ‘ordinarie pastime is to disguise them selfes, to go laugh at the Courtisanes houses, and in the shrovyng tyme, to ryde maskyng about with theym’.36 Clearly, social, political, and clerical élites participated freely in popular activity.

But it was also seen as their job to control it. Carnival was not, or not only, the unregulated spontaneous activity sometimes assumed.37 One might think that the occasional attempts to regulate or ban masking confirm the polarisation of official and unofficial culture proposed by some theories of Carnival. Yet if that tension is there, it is not the whole explanation. Except in some very specific circumstances of violent crime or existing unrest, the authorities show little desire to prevent, or even much restrict, the activities of carnival masking. Most regulations seem more permissive than restrictive, and generally show the rulers engaging with carnival masking rather than distancing themselves from it.38

There were certain regulations. In Rome repeated edicts laid down that no-one was to mask as a cardinal, bishop or priest, or to go masked into churches; no one was to throw anything rotten or nasty; no-one was to carry arms, offensive or defensive; masking in the streets must cease after 2 a.m.39 None of these edicts seem necessarily designed to curb the central play of Carnival. The ecclesiastical prohibitions could be seen as censorship, but equally suggest an attempt to allow Carnival and the Church to coexist. The time restriction seems designed to permit masking while allowing the city to continue operating as a social and commercial unit.

The ban on arms could be interpreted as neutralising any attempt to use Carnival as a means of popular or factional uprising. But it is equally likely to be directed at random street violence, and the use of carnival disguise to carry out private vendettas and revenge. These were recognised dangers of carnival time when large bands of excited and disguised citizens were wandering the streets in the dark. There are plenty of records of assaults, robberies, and blood-feud attacks during the Carnival.40 But such assaults seem to work against, rather than with the generally communal purposes of carnival masking. In them the masker remains himself under his mask, pursuing private ends against another individual, rather than joining the anonymised release of the group. Group violence by classes and factions might be thought a more genuinely significant problem, but on the whole in Italy this seems not to have occurred.41

In France, carnival activity was frequently organised by temporary ‘kings’ appointed for the season and it may be that this overt pattern of parodic power-structures contributed to the occasional apparent appropriation of Carnival in France to attempt real political change.42 The best documented case studied in recent years is the Carnival at Romans in 1580. The pre-Lenten festivities of this year did indeed become the occasion for an armed uprising. From a distance this revolt of the ‘Leaguers’ (largely peasant and bourgeois) against the heavy and arbitrary tax system looks like a perfect example of the use of Carnival’s dissolving of social structures and power systems to effect real rather than symbolic change.43 But, as we might expect, the situation was less simple than this implies. Various long-standing factions made combative use of the Carnival, electing competing Carnival Kings, and armed action broke out when a masked ball held by one set of kings was attacked by masked followers of another. This violence between carnival maskers involved all sides, not just the ‘popular’ or ‘powerless’ against the authorities, or the Carnival against the non-Carnival world. Of course the episode depends upon the nature of Carnival: practically, a time of excitement and confusion when large groups of people are wandering about masked at night and normal restraint is partly lifted; more conceptually, a time of alternative, if playful, power-structures, when it is acceptable for people to partly abandon their normal identity and express comic aggression. But these conditions could be used for many different ends – sometimes stabilising and conservative, sometimes self-regulating or genially communal, sometimes aggressive and revolutionary.

At almost the same moment, in fact, there was an attempt by the other end of the social scale to appropriate carnival masking for its own ends. In the early 1580s the king, Henry of Navarre, is regularly recorded as rioting masked through the streets of Paris with his companions around Shrove Tuesday. In 1584 the King and his brother:

… went together through the streets of Paris, followed by all their favourites and mignons, mounted and masked, disguised as merchants, priests, lawyers etc, tearing about with a loose rein, knocking down people or beating them with sticks, especially others who were masked. This was because on this day the King wished it to be a royal privilege to go about masked.44

The élite felt an equal need to use the occasion of Carnival to express their own tensions.

There are other opposing categories. Was carnival masking equally for rich and poor, old and young, men and women? If riches were not a prerequisite, they certainly could contribute to the display of carnival masking. Not only the masks themselves, but the costumes that went with them became increasingly exotic and flamboyant, a means for wealth to express and celebrate itself. Yet carnival masking was by no means confined to the rich. One commentator even claims that the carnival mask is liberating precisely because coprela povertà di quelli, che sono malvestiti (‘it hides the poverty of those who are badly dressed’).45 It offers an easy way to escape from poverty, as well as to flaunt riches.

The polarisation of old and young seems clearer. Carnival was seen as especially the territory of the young. In Ferrara masking was inaugurated per piacere i zoventude (‘to please the young people’), and one of the reasons given by Tasso for older people not masking is that what pleases youth is intolerable to age.46 Many of Burchard’s cardinals were no more than teenagers, which immediately modifies our sense of their status and what they were doing. This is not to say that older people did not mask, only that it was held to be particularly the province of the young, who perhaps needed more outlet from normal restraint for their wild energies than did their elders.47

It is harder to be clear about attitudes towards the participation of women. It is plain that both sexes did mask: pictures of carnival festivity, Cecchi’s references to men and women, the mask-makers’ song, and comments from foreign observers in Italian and Spanish cities all confirm that women took part. But often they take a secondary role. Descriptions of carnival festivity imply that it was the young men who dominated: the eggs and perfumes thrown at the women watching at the windows show them in their more traditional role as spectators, at least of the street masking. The ambiguity is compounded by the common carnival/Kalends disguise of cross-dressing. Young men seem frequently to have disguised as women, an easy and striking way to escape, or pretend to escape, from their usual social roles and expectations and play with the identity of another gender.48 Prostitutes, on the other hand, are recorded as plying in men’s clothes;49 but it is not clear quite how far this was an acceptably liberating disguise for other women.50 Shakespeare plainly thinks so: Jessica escapes from Shylock’s house disguised as a boy torchbearer in a Venetian masquerade, and the same motif is prominent in Italian comedies.51 While this may tell us more of the illusions of theatre than of actual practice, cross-dressing by both men and women clearly contributed to the delightful instability of the carnival ambience.52

Motivations of Masking

With the city streets apparently full of maskers, how far can we tell why they masked? Various reasons were offered at the time, and have been later, to try to explain this temporary madness, though the very plethora of motivations suggested testify to the elusive multivalency of Carnival. Like all cultural phenomena of the time, Carnival could mean different things to different social groups.53

The young nobles of Florence apparently wished to control and refine the pre-existing popular sports into something more consonant with their own élite culture. They admired the elaborately masked carnival floats of Piero di Cosimo, who, Vasari says, was valued for his capriccioso e di stravagante invenzione (‘witty and extravagant invention’) and his improvements d’ornamento e di grandezze e pompa (‘in ornament, grandeur, and pomp’).54 Their view of the purpose of the masking thus combined cultural display and élite magnificence with ‘witty extravagance’, an elegant version of the excess proper to Carnival. Duke Ercole of Ferrara, more personally, went masquerading each year cerchando la sua ventura, literally ‘seeking his fortune’ in lavish New-Year’s gifts,55 but also, presumably, implying that as a masker he cast himself out from normality onto the sea of chance.

These motivations are clearly class-specific. How far can we determine those of ordinary carnival maskers? In broad terms Carnival could be explained as a purgative release – a chance to have a good time, which would get rid of tensions, unleash fantasies, and generally provide a festive regeneration.56 As Cecchi reminded his Renaissance audience, carnival masking would let them disfogare i cappricci (‘release their fantasies’); it was Il remedio e l’antidoto ordinato / Per purgare i cervelli (‘the remedy and antidote prescribed to purge the brains’).57 The primary function of the mask, to disguise, suggests that the sense of release from normal identity was central to Carnival. A late commentator on Garzoni, an opponent of carnival masking, offers four revealing benefits that the visor might bring:

… rende la persona audace, per non esser conosciuta, coprela povertà di quelli, che sono malvestiti, insegna di parlare a quelli, cho sono vergognosi, & dona la libertà alle persone di gravità, & di rispetto.58

… it makes one bold, because his person is not known; it hides the poverty of those who are badly dressed; it teaches the shamefaced to speak, and it gives freedom to personages of gravity and respect.

All these are based on ideas of liberation from one’s self or social position: the masker is freed from the constraints of community, poverty, shyness, or rank, and given the courage of anonymity.

The extremes of fantasy in Italian carnival costumes – the wild men, the exotic foreigners, the devils, the grotesque phallic noses – must also have been liberating. They could involve direct inversion, as men dress as women, nobles as peasants, young men as old: but this inversion does not seem to have been formalised into the socio-political role-reversal of the Roman Saturnalia. Equally, the masks express little focused satire or criticism of any authority or group.59 More probably the point was simply to move as far as possible from one’s normal self, for the pleasure of the contrast, and the sake of feeling oneself new.

Some contemporary commentators suggest, though, that this principle of difference may be yet further qualified. Castiglione’s Cortegiano (1528) observes that while contrast was important so, at least for the élite, was the continuing presence of the masker’s original identity:

… lo esser travestito porta seco una certa liberta e licenzia … il che accresce molto la grazia: come saria vestirsi un giovane da vecchio, ben però con abito disciolto, per potersi mostrare nella gagliardia; un cavaliero in forma di pastor selvatico o altro tale abito, ma con perfetto cavallo, e leggiadramente acconcio secondo quella intenzione … Però ad un principe in tai giochi e spettaculi, ove intervenga fizione di falsi visaggi, non si converria il voler mantener la persona del principe proprio, perché quel piacere che dalla novità viene ai spettatori mancheria in gran parte, ché ad alcuno non é novo che il principe sia il principe.60

… to be in a maske bringeth with it a certaine libertie and lycence … which augmenteth the grace of the thing, as it were to disguise a yong man in an olde mans attier, but so that his garments be not a hindrance to him to shew his nimblenesse of person. And a man at armes in forme of a wilde shepeheard, or some other such kinde of disguising, but with an excellent horse and well trimmed for the purpose … Therefore it were not meete in such pastimes and open shewes, where they take up counterfeiting of false visages, a prince should take upon him to be like a prince in deede, because in so doing, the pleasure that the lookers on receive at the noveltie of the matter shoulde want a great deale, for it is no noveltie at all to any man for a prince to bee a prince.’61

Castiglione emphasises the importance of the distance between real and assumed identity; yet he also asserts that much of the pleasure lies in the overt interplay between the two. Release and anonymity are important, but should remain to some extent symbolic rather than complete. Earlier in the discussion, he suggests that the token of anonymity provided by the mask is more significant than actual disguise. So behaviour which is unacceptable at normal times may be appropriate, fuorché travestito, e, benché fosse di modo che ciascun lo conoscesse, non dà noia (‘if he is disguised: and and even if this were in such a way that everyone recognised him, it would not be a problem’ or possibly ‘give offence’).62 The importance of carnival masking, Castiglione suggests, is that it is, and is acknowledged to be, a game. That is its pleasure and its purpose. Yet that is also what allows the person of authority to condone and partake in it. His remarks are specifically directed at the ‘Courtier’, and ordinary late-medieval Italian carnival maskers may not have shared his sophisticated concerns. But the interplay of self and other must also at some level have been an important element in their masking.

The behaviour of the maskers is also revealing. Stories about Carnival suggest that one important feature was rough practical joking and horseplay. The wild missile fights seem an almost institutionalised motif. A sixteenth-century visitor to Marseilles observed:

… sahe ich die knaben von der statt einander mitt pomerantzen, wie be uns sie mitt scneeballen thundt, werffen; es sinndt auch die fürübergehende nitt sicher, dann umb dieselbige zeitt die pomerantzen gar gelb, lindt unndt anheben zu schanden zewerden, also dass man sie schier umbsonst weg gibt, weil ganze schiff vol daselbsten ankommen; werden jährlich in der fassnacht viel tausendt von den knaben verworffen.63

… I saw a great many good-for-nothing fellows … throwing oranges, just as we throw snowballs. Even the passers-by were not safe from them, for at this time of year entire cargoes of this fruit come in, and as they become over-ripe they are sold ridiculously cheap. At every Carnival thousands of them are used in this manner.64

Carnival itself was partly defined as contest and mock violence, as the Europe-wide visual and literary theme of ‘The Battle of Carnival against Lent’ confirms.65 Although violence is nominally playful, with battles of eggs and oranges, pig-slaughter and castle-smashing, Carnival also becomes a natural context for the ad hoc enaction of comic aggression and revenge.

A Roman carnival story from Castiglione’s Cortegiano illustrates this. The Cardinal of San Pietro in Vincolo watches from an upper window while Bernardo (later himself Cardinal) Bibbiena66 indulges his habitual pleasure quando son maschera, di burlar frati (‘whan I am in maskerie to play Meerie Pranckes with friers’). Having tricked a friar onto his horse, he spurs it into a wild career:

Imaginate or voi che bella vista facea un frate in groppa di una maschera, col volare del mantello e scuotere il capo innanzi e ’ndietro, che sempre parea che andasse per cadere. Con questo bel spettaculo cominciarono que’ signori a tirarci ova dalle finestre … di modo che non con maggior impeto cadde dal cielo mai la grandine come da quelle finestre cadeano l’ova, le quali per la maggior parte sopradi me venivano; ed io per esser maschera non mi curava, e pareami che quelle risa fossero tutte per lo frate e non per me.67

Imagine with your selves now what a faire sight it was to beholde a Frier on horsebacke behind a masker, his garments flying abroad and his head shaking too and fro, that a man would have thought he had been alwaies falling. With this faire sight, the gentlemen began to hurle egges out at the windowes … so that the haile never fell with a more violence from the skye, than there fell egges out from the windowes, which for the most part came all upon me. And I for that I was in maskerie, passed not upon the matter, and thought verily that all the laughing had beene for the Frier and not for me.68

Bernardo finally realises that the ‘friar’ is a disguised groom of the Cardinal’s, set up to trick and discomfit him. The ambivalence of the Church towards masking games is neatly encapsulated. Clerics were forbidden to mask, and maskers forbidden to disguise as clerics: yet the Cardinal cheerfully and publicly sanctions the playful breach and exploitation of both regulations. The story illustrates a web of trickery and comic aggression between friends, acquaintances, and strangers that seems wholly natural to Carnival.

Masks are likely to have made an important contribution to the licence for such relatively ‘harmless’ and comic aggression. For the aggressor the mask conveys anonymity (either real or symbolic) which nominally releases him from normal guilt or responsibility. It would be unacceptable for Bibbiena to play such tricks on friars in his own unmasked person. The stories also suggest the effect of masking on the object of aggression. The strangeness of carnival attire tends to distance and dehumanise the wearer, allowing aggressors freer rein, and again removing the normal sense of responsibility.69 Whether the disguise is truly impenetrable or merely symbolic, the mask seems to signal a (potentially dangerous) freedom from normal restraint between individuals.

PLATE 3: Carnival maskers serenading; in the background, a fight. Crispijn van de Passe Nieuwen Ieucht-Spieghel [?1620] 65. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, Fr. 1354–9.

© Reproduced by permission of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Yet if such licence for mock aggression is one meaning of the carnival mask, it also seems, paradoxically, to strengthen the communal feeling and intimacy between maskers. This is manifested partly in the sexual licence for which Carnival, in fact or in legend, was famous: ‘II est au carnaval ou chacun fait l’amour’.70 The phallic maskers described by Burchard are not at all unusual: many carnival disguises were erotic, as the cross-dressing, and much noted participation of the courtesans shows. The egg-throwing to and from the women at the windows is an amorous game. According to Thomas Platter, in the Spanish carnival masking offered a specifically sexual licence, especially for those normally kept in restraint:

Da sahen wier ein mascaraden … eine anderst die andere vermummet. Unndt obschon dass frauwenzimmer dass gantze jahr durchauss gar sträflich eng unndt eingezogen gehalten wirdt, also dass sie schier gar nitt dörfen mitt frembden männeren oder knaben sprach halten, also eyferig sindt sie … so sindt sie doch die gantze fassnacht von solchem allem gefreyet, dörfen mitt ihren gespilen unndt bekannten vermummet herumb laufen, wie ich dann der weiberen viel gesehen also vermummet; da gibt es dann viel (cocus) gauchen, obschon der früling noch nitt vorhanden. Und miessen die mannen solches ihren weiberen, oft wider ihren willen, lassen passieren, weil sie es von alter also härgebrocht haben.71

We saw numerous masked people … with every kind of costume imaginable. The women too take their part. Throughout the year they are so severely restricted that they are not allowed to talk to strangers … But at carnival time there are no such shackles and hindrances. They put on masks and run the streets in complete freedom with their friends and acquaintances. So for more than one husband, the cuckoo sings before spring comes. No matter, at such times they are no longer the masters and must confirm to common usage.72

Normal sexual hierarchies are subverted, not by anarchy or radical reform, but by the ‘common usage’ of inversion.

There are frequent riotous, if mythical, stories of husbands and wives in masks unwittingly committing passionate ‘adultery’ with each other. One pertinent German example tells of a married couple who, both masked, meet unwittingly at carnival time and ‘indulged their sudden fancy on their way in the penumbra of a cloth-worker’s shop in the market place, and never did the hallowed joys of matrimony taste like the forbidden fruit of infidelity’. The husband, wishing to discover his partner’s identity, cut a piece from her dress and the next morning all came out. ‘Denial was impossible, but the one happened to be as guilty as the other’.73 The tale, fact or fiction, demonstrates what was clearly agreed to be an effect of carnival masking: by heightening excitement and suspending identity, sexual desire could be more freely and intensely fulfilled without the trammels of familiarity, responsibility, or consequence.

But it is the power of group, rather than individual bonding which the masks seemed particularly to enhance. Carnival was the chief occasion for masking in gangs, rather than separately; one of its most powerful functions was to subdue the sense of individual separateness in favour of anonymous but communal bonds. The mask, after all, is par excellence a public, not a private face. To mask together implies trust, and acceptance of one’s fellow maskers. The mask subdues the factors that separate individuals, whether they are personal, social, or circumstantial, allowing the sense of group identity to ride uppermost.74

The identity of this group is very variable. It may be, as Bakhtin implies, ‘the folk’ or ‘the people’ who by masking together liberate and assert their group identity against authority, the élite, the official culture.75 But equally it may be ‘the people of our town’ – including artisans, nobles, and clergy.76 Or it may be ‘the young people’ against their elders, since masking is so often seen as a youthful activity.77 It may be a class division: carnival masking is sometimes seen as the province especially of the popolani, at other times as a particular habit of the young noblemen. But in all cases the prime effect, facilitated by the masks, seems to be a sense of belonging, the dissolving of individuality. Since the significance of the group itself is so fluctuating, it is hard to offer any one explanation of Carnival as either ‘popular’ or ‘élite’, ‘conservative’ or ‘revolutionary’, ‘structured’ or ‘spontaneous’. Whichever group’s identity is enhanced by the masked play may determine the use that is made of Carnival at that particular time, whether for anarchic, conservative, aggressive, or companionable ends.78

Carnival in Northern Europe

Northern Europe shared, or perhaps adopted, many of the carnival customs of the South. Although the many surviving Fastnacht plays show that drama had a prominent role, there is somewhat less evidence for organised masking shows. Informal street masking, however, was energetic and widespread, as were the more domestic masked house visits and dances.79 Moreover, Reformation critics of popular Roman Catholic customs offer some vivid new perspectives on carnival masking.

Civic shows were by no means entirely absent: one of the best documented of all European carnival spectacles was at Nuremberg,80 where the Schembartlauf and its elaborate costumes were, after its demise, carefully illustrated in a series of manuscripts. This Shrove Tuesday spectacle – a masked street dance attended by masked runners – is reconstructed by Samuel Sumberg. First:

… came the heralds of the Schembartlauf, on horse and on foot, throwing nuts to the boys and eggs filled with rosewater to the ladies in the windows. A howling mob of devil guisers followed them, amazing and frightening the crowd by their rough theriomorphic costumes and the fire and ashes they threw. A way was thus cleared for the troop of handsomely masked dancers who came leaping through the streets to the rhythmic jingle of strings of bells on their person and the music of fife and tabor.81

The masks formed a significant and privileged part of the celebration. By the late fifteenth century the Nuremberg authorities, like others in Northern Europe, were trying to restrict popular carnival masking, ordering in 1469 that ‘no one, man or woman … either by day or by night shall reverse their clothing or alter it otherwise, and especially that they shall not change or distort their visage with any sort of thing … but show it so that they are well recognisable’.82 But masks were explicitly permitted by the council to the dancers and the Laufer, the chosen band of guisers who surrounded and protected the dance.

The Schembart raises some particular questions on the issue of carnival masking and control. Like many such customs it was apparently suppressed in the mid-Sixteenth century as a threat to order, by authorities who had always exercised fairly strict controls on who might perform and in particular who might mask. In 1539 Hans Sachs, a writer much linked with Fastnacht, wrote a poetic account of the Schembartlauf, both acknowledging and refuting its association with disorder and uprising.83 His description emphasises the common carnival impression of chaos, inversion, and wild energy. But each detail of the dance is then carefully rationalised historically: it was granted to the Butchers’ guild to commemorate their loyalty to the authorities at a time of popular uprising; its route follows that of the uprising; the wild dancing indicates the disorder of rebellion; the sumptuous costumes, the rebels’ pride; the youth of the dancers, their immaturity; the firework-throwing, their inconsiderate arrogance. The poem suggests that the Carnival, through commemorating revolt, demonstrates the profound importance of order and social restraint. The masks, grotesque and beautiful, both express and warn against anarchy. They are, Ein verborgener Spiegel /Der gmain zu einem sigel /Fursichtig sich zu hüten /Vor auffrürischem wüten (‘a hidden mirror that warns you to safeguard against any rebellious rages’).84 Despite the evident tension between licence and restraint, it seems (as perhaps with Armistice Day ceremonies today) that even contemporaries could paradoxically perceive the same spectacle as either celebrating, or deploring, the disorder it commemorated.

More common in Northern Europe, however, seems to have been the informal street masking that accompanies Carnival. Impromptu street masking was combined with house visits, sometimes relatively elaborate. In 1521 Dürer, visiting Antwerp, records Ich hab den Fockorischen ein Visierung zur Mummerei gemacht … dem Tomasin zween Bogen voll gar schön Mümmerei gemacht (‘I made a drawing of a mask for Fugger’s people for masquerade and … two sheets of beautiful little masks for Tomasin’). Attending a Shrove Tuesday banquet shortly after, he writes und auf dem obgemeldten Fest warn gar viel köstlicher Mummers und sonderlich Tomasin Pombelli (‘and to the above mentioned feast came many very splendid masks, especially Tomasin Bombelli’).85 The house-visits were not always so formal. Prohibitions in Ghent and other towns specifically prohibit maskers from demanding or filching food from householders, a ‘stealing right’ apparently traditional in the Low Countries.86 Visits like these, which depend on interaction between visiting maskers and unmasked householders, really belong to the tradition of mumming, separate from but related to Carnival, that will be considered in the next chapter.

The street masking attracted polemic from reformers, in particular Sebastian Brant’s immensely popular Ship of Fools (1495) and its derivatives, and Thomas Kirchmeyer’s attack on popular Roman Catholic ‘superstitions’, Regnum papisticum (1553). Kirchmeyer claims that at German Fastnacht old and young, men and women, join in mad, gluttonous licence: Cuncta licent fiuntque, fere, nec ommittitur ulla (‘All thinges are lawfull then and done, no pleasure passed by’). As part of this uproar (here with a sixteenth-century English translation):

Ast alii horribiles vultus, torvamque figuram

Daemonis induti, tota spacientur in urbe,

Atque occurrentes terrent, puerosque sequuntur.

Pars currant nudi, faciem duntaxat & ora

Contecti larvis, ne cognoscabantur ab ullo.

Vestitium sexus proprium commutat uterque

Foeminea tum namque viri, contraque virili

Ornantur passim lascivae veste puellae.87

Some againe the dreadful shape of devils on them take,

And chase such as they meete, and make poore boyes for feare to quake.

Some naked run about the streetes, their faces hid alone,

With visars close, that so disguisde, they might be knowne of none.

Both men and women chaunge their wede, the men in maydes aray,

And wanton wenches drest like men do travell by the way.88

He also records maskers in skins and fearful masks of bears, wolves, wildcats, lions, cattle, and birds. Kirchmeyer’s observations are supported by a late-fifteenth-century Nuremberg Fastnacht play by Hans Folz, Ein Spil von der Fasnacht, in which a Burgher refers to masks of calves, apes, donkeys, swine, and fools, while an Artisan talks of cross-dressing and inside-out clothes.89 The three main categories – animals, cross-dressers, and devils – recall the celebrations of Kalends, older and possibly less urbanised forms than those predominating in Italy.90

The Ship of Fools, printed uff die Vasenacht, has intimate connections with Carnival. But it was not until the second (1495) edition that Brant added a section Von fassnacht narren (‘Of Carnival Fools’).91 He speaks of maskers blackening themselves with soot, and running about like goats. Locher, Brant’s Latin adaptor, adds vivid details of the ‘hired hair’ (conductos … capillos) and ‘bought teeth’ (dentes emptos) worn by the maskers.92 Brant and his imitators offer a more complex moral criticism of carnival masking than Kirchmeyer’s straightforward contempt for superstition. Anonymity is only pretended, insists Brant; the blackened faces are the devil’s insignia, revealing the true allegiance of the maskers. Locher adds the tale of a carnival devil-masker claimed and carried off by Satan. He and others also affirm the erotic play of Carnival, asserting that the seduction of chaste wives is the chief purpose of the maskers who seem to have combined house visits with their street masking.93 A woman in the Nuremberg carnival play claims that her own reason for cross-dressing is to avoid the unwanted attentions of male maskers.94

If the Reformation produced criticism it also generated a fascinating defence of carnival masking from a young resident of Mainz. Appropriately youthful, eighteen-year-old Theodore Gresemund published a dialogue de furore germanico diebus genialibus camisprivii (‘on German madness during the merry days of Carnival’), in which a critic is countered by a young carnival masker. While relying chiefly on common medieval arguments about the value of recreation, the dialogue also presents an unusually vivid dramatisation of the attitudes of an ordinary, if educated, carnival masker.

Cato, the critic, typically objects to the insane, lascivious, and emasculating practices of German Carnival. The author’s persona Podalirius, retorting that the Italians are far worse, offers two main defences: that carnival masking is not rabies (‘insanity’) but mentis honesta relaxatio (‘proper easing of the mind’); and that while the sober domestic entertainment recommended by Cato is suitable for the old, Iuvenes vero aliud decet (‘something different is appropriate for the young’), who are more energetic, joyful, playful, and hot-blooded. The debate becomes more specific on the issue of masks. Cato sees them as the primary agents of the corrupting inversions and reversals of Carnival:

Cuncta vertiginosa quadam rabie rotentur: et domini in servos: et mulieres in viros: et adulescentes in virgines: et iuvenis in vetulum: et pulcher in deformem: & homines in larvatos kakodemones transmutantur.95

Everything is up-ended by this dizzy madness: masters are transformed into servants, women into men, boys into girls, young into old, beautiful into hideous, and men into masked demons.

Podalirius’ response is brief but striking: Nos vero soli immutabiles? Marpesiam cautem duricia vincimus? An soli nos calybei aut amantini sumus? (‘Are we alone immutable? Harder than marble? We alone steel or adamant?’). The implied youthful allegiance to transformation, mutability, and dynamic human metamorphosis is unlike the officially articulated wisdom of most medieval thinking, closer to the developing humanist positions of writers like Pico della Mirandola.96

There follows a sharp vignette of masking practice as Podalirius, rather implausibly, persuades Cato to join him and they arrange their costumes. Podalirius offers soot, a mask, or a donkey skin as disguises. When these are nervously rejected by the educated Cato as demeaning (me asinum vocitabunt homines – ‘people would call me a donkey’), Podalirius encourages him onto safer ground by suggesting that he might represent the academically respectable figures of Midas with ass’s ears or, the donkey skin furnished with claws to represent a lion’s pelt, Hercules. He likewise reassures the anxiously self-conscious Cato that this is only a fantasy game in which he does not have to lose his own identity entirely. Cato agrees to mask si solo amictu soloque gressu vultu ac voce Alcidem referam. Cetera vero sim Cato (‘If I represent Hercules only in clothes, gait, face, and voice. In everything else I shall be Cato’).97 Podalirius himself decides, since he is too young to have much of a beard, to mask as a woman. These excited preparations are, unfortunately, interrupted by a victim of street violence who frightens Cato off, and the dialogue is halted. Its mixture of formal argument and personal participation throws a revealing and unusual light on popular Germanic carnival masking.

This youthful delight in the masks of Carnival seems to have persisted despite the continuing objections of reformers. Over a century later Rodolph Hospinian in Zurich, in one of many fierce academic denunciations, revealed that still at carnival time per universum fere orbem Christianum, homines sic prorsus insaniunt (‘throughout almost the whole Christian world, people go completely mad’):

Omnes autem personis tecti, ne a quoquam agnoscantur, & frequenter veste foeminea, interdum etiam foeminae veste virili, tanquam si pulchrum aut honestum foret sexum mentiri. Nonnunquam insuper quidam sic deformati, ut figuram omnem humanam prorsus exuisse diceres: nam cornuti, rostrati, dentibus aprinis, flammantibus oculis, fumum et scintillas ex ore exhalantes, curvis unguibus, caudati, hirsuti, denique & monstrosi terribilesque cacodaemonas videri atque timeri affectant.98

For everyone is hidden in a mask lest they should be recognised by anyone. Men are often in women’s clothes, and also women in men’s clothes, as if to belie their fair and virtuous sex. Some, besides, are so deformed that you would say they had put off all human appearance: for with horns, beaks, boar’s teeth, flaming eyes, breathing smoke and sparks, curved talons, tails, shaggy hair, they aim to seem, and to terrify, like monstrous and terrible demons.

The ancient Kalends stereotypes are still going strong.

Carnival in Britain

Una omnium regionum Anglia eiusmodi personatas belluas hactenus non vidit, nec quidem vult videre, quando apud Anglos, in re hac prae aliis, certe sapientiores, lex est, ut capitale sit, si quis personas induerit.99

Among all the parts of the world, only England has not seen such masked beasts, nor does it want to, because among the English (who more than others are truly wise in this matter) there is capital punishment, that is the death penalty, for anyone who wears these masks.100

Against the background of carnival masking in mainland Europe, what do we find in Britain? On the whole there is very little sign of the communal, public, street festivity and masking in the period leading up to Shrovetide that marks the height of the carnival season. The quotation above from Polydore Vergil, though clearly mistaking the legal position, suggests that even at the time Britain was thought of elsewhere as a non-masking, non-Carnival country.

If ‘Carnival’ is extended to include all the winter festivities stretching from Christmas to the beginning of Lent, there is more to be seen: some of the activities of European Carnival did take place at various times and places between Christmas and Shrovetide, although apparently in a more haphazard, less communal manner.101 The adjuncts were there: the association of Shrovetide with pancakes and sausages, and Lent with herring, especially dried herring, was clearly traditional.102 Football and cockfighting are common, and it was often a day of holiday and inversion games for schoolboys.103

But signs of masking, and especially large-scale public street masking, are few.104 Official and legal records reveal little, and English translators of foreign commentators on the period of Carnival tend to omit or modify their attacks on masking.105 However, an isolated incident from Norwich suggests that organised street shows were not unknown, even if they were more of an exception than a rule. In an episode now known as ‘Gladman’s Insurrection’, a merchant of Norwich was convicted of taking part in a costumed parade on 22 January 1443, which became the pretext for an attack on the Priory. The complaint laid with the authorities does indeed suggest that Gladman not only took part in a carnivalesque masquerade, but that he exploited its revolutionary possibilities, turning it into a deliberate expression of inversion and incitement to violent rebellion. He is accused of riding through Norwich ‘as a king with a crown and sceptre and sword carried before him’, while 24 others rode ‘in like manner before John Gladman with a crown upon their arms and with bows and arrows as varlets of the crown to the lord king’. Accompanied by one hundred others they rang the bells and threatened to burn the Priory and kill the Prior and monks.106

If we had only this statement to go on, then both the fact of carnival disguising in Britain, and its radically subversive potential might seem to be confirmed. Yet the context as usual suggests something more complicated. As at Romans in 1580, the problem in Norwich was complex and long-standing, the unrest at the parade only one moment in a continuing argument. Once again the masquerading seems to have been a useful and vivid pretext, rather than itself a cause or manifestation of conflict. An appeal made some five years later to clear Gladman’s name offers a completely different explanation of the events. According to his friends John Gladman, ‘a man of sad disposicion’:

… of disporte as is and ever hath ben accustomed in ony Cite or Burgh thrugh al this reame on fastyngong tuesday made a disporte wt his neighbours having his hors trapped with tyneseyle and otherwyse dysgysyn things crowned as king of kristmesse in token that all merthe shuld end with ye twelve months of ye yer, afore hym eche moneth disgysd after ye seson yerof, and lenten cladde in white with redde herrings skinnes and his hors trapped with oyster shelles after him in token yt sadnesse and abstinence of merth shulde followe and an holye tyme; and so rode in diverse stretes of ye Cite wt other peple wt hym disgysed making merthe and disporte and pleyes.107

The ‘horrible articles’ of the accusation of rebellion against him ‘thei never ment it ne never suych thyng ymagined.’

It is impossible to judge the relative truth of the different accounts; but since the deposition of Gladman’s supporters must have been intended to sound plausible, the appeal to tradition is presumably accurate. The description of the parade sounds appropriate to the wider ‘carnival’ season if not to ‘fastyngong tuesday’ itself (Gladman’s show having apparently taken place five weeks earlier): Carnival, here typically English as the ‘king of cristemesse’, accompanied by costumed representatives of the twelve months, plays out the opposition to Lent with his fishy reminders of privation and penance. A similar ‘Carnival against Lent’ motif may be hinted at in the brief mention of a Jack a’ Lent who rode in a March parade in London in 1553.108 The emphasis of the deposition is that the purpose of all this spectacle was ‘disporte’ – mirth, disport, and play constantly recur through the account. The appellants apparently believed that ‘disport’ was generally taken as a valid primary reason for a carnival riding, and that people would accept that even those of ‘a sad disposicion’ might well indulge in such activity at this time of year purely for the purposes of communal play with their neighbours. It must have been at least credible that the intention of subversive uprising attributed to the participants was something they had never ‘meant or imagined’.

The terms of the appeal suggest tantalisingly that public street masquerades of this kind ‘hath ben accustomed in ony Cite or Burgh thrugh al this reame.’ But fascinating as this episode is, it is nonetheless very isolated. Apart from the much more confined riding of ‘twoo disguysed persons called Yule and Yule’s wife’ at York on St Thomas Day (21 December), which is itself referred to as a ‘custom maynteyned in this Citie, and in no other Citie or towne of this Realme to our knowlege’, only the London record suggests anything comparable.109 It should also be pointed out that none of these events were specifically said to be masked: disguised meant no more than ‘in costume’.110

The dearth of evidence leads us to the conclusion that what was accustomed was a much more general kind of ‘disporte’. More informal public street masking, although equally detached from Carnival proper, is evidenced later in Scotland. Various post-Reformation kirk and presbytery sessions accused parishioners of ‘dansyng and guysing’ through the streets on winter nights: the impromptu quality of the masking is revealed by the costumes at Elgin in 1598, ‘his sisters coat upon him … thair faces blaikit … a faise about his loynes and ane kerche about his face’.111 The frequency of the prohibitions imply a widespread, but nonetheless small-scale practice.

But given the lavish and diverse evidence of carnival masking from the countries of mainland Europe it is hard to believe that Britain was full of Shrovetide masks and processions that have simply left no trace in the records. This is not to say, though, that Britain was without popular masking games, although they were not focused on the Shrovetide season, and rarely matched the full-scale public festivity of European Carnival. They are found not in what we think of as ‘Carnival’, but in the related if less communal play of ‘mumming’.

Notes

1 Alessandro Ademollo Il carnevale di Roma nel secoli XVII e XVIII (Rome: A. Sommaruga, 1883) 21.

2 Thomas Middleton’s Inner Temple Masque or Masque of Heroes (1619) declares of the dying Christmas that ‘he may linger out till Candlemas’; Candlemas appears in an Antimasque ‘ill associated’ with Shrove Tuesday, which that year was only a week later: A Book of Masques in Honour of Allardyce Nicoll edited T.J.B. Spencer and others (Cambridge University Press, 1967) 261, 263.

3 Fynes Moryson Itinerary [1617], of Italy: see Shakespeare’s Europe: Unpublished Chapters of Fynes Moryson’s Itinerary edited Charles Hughes (London: Sherratt and Hughes, 1903) 457. See, for France, van Gennep Manuel de folklore 1,3: 870–71. As Samuel Kinser points out, ‘Carnival, hitched to the moving date of Ash Wednesday, changes its character as well as its date in some details with every performance’: ‘Why is Carnival so Wild?’ 44.

4 Rio is of course in the Southern hemisphere; Notting Hill is an offshoot of the tropical Trinidadian Carnival.

5 For example, Theodoricus Gresemundus Podalirii Germani cum Catone Certomio, de furore germanico diebus genialibus carnisprivii dialogus ([?Mainz]: [? 1495]) A3v; Polydore Vergil De rerum inventoribus (Basle: J. Bebelius, 1532) 310–14; Rodolphus Hospinianus Festa christianorum: hoc est de origine, progressu, ceremoniis et ritibus festorum dierum christianorum (Zurich: J. Wolph, 1593) svv Ianuarius, De Quinquagesima.

6 For information on carnival practices see: Ademollo Carnevale di Roma; Felipe Clementi Il carnevale romano nelle cronache contemporanee (Citta di Castello: Edizioni R.O.R.E.’Niruf, 1938–39); J. Caro Baroja El carnaval: analisis historico-culturel (Madrid: Taurus, 1965); Pleij Blauwe Schuit; Edward Muir Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton University Press, 1981) 156–81; Fabrizio Cruciani Teatro nel rinascimento, Roma 1450–1550 (Roma: Bulzoni, 1983); Dietz-Rüdiger Moser Fastnacht-Fasching-Karneval (Graz: Kaleidoskop, 1986).

7 For arguments that carnival festivity was primarily unregulated, or subversive, see e.g. Bakhtin Rabelais chapter on ‘Popular and Festive Forms’; E. le Roy Ladurie Carnival in Romans: A People’s Uprising at Romans, 1579–80 translated Mary Feeney (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981); Michael Bristol Carnival and Theater: Plebeian Culture and the Structure of Authority in Renaissance England (New York and London: Methuen, 1985). For some revised views see City and Spectacle in Medieval Europe edited Barbara A. Hanawalt and K.L. Reyerson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), especially papers by Lindenbaum and Ruiz; Humphrey Politics of Carnival.

8 See chapter 4 on ‘Mumming’. For élite activity see, for example, Duke Ercole of Ferrara who himself went from house to house, collecting New Year’s presents: see below 66. Rich households also gave masked balls which were gatecrashed by companies of young men, also in masks: see chapter 8 on ‘Amorous Masking’.

9 For example, Maximilian J. Rudwin The Origin of the German Carnival Comedy (New York: Stechert, 1920): Baroja El carnaval; even Pleij Blauwe Schuit. Some scholars wished to derive carnival from carrus navalis (‘ship-chariot’) and relate it to the ship processions in honour of the Germanic god Nerthus recorded by Tacitus.

10 The earliest ‘carnival game’ recorded in the quotations in DuCange is a thirteenth-century professional war-game played before the Pope on Quinquagesima Sunday. The other synonym, carnisprivium, also appears from the twelfth century, but only in a context of fasting. It often means just ‘Lent’.

11 Muir Civic Ritual 160–61.

12 See Robert Davidsohn Storia di Firenze transited G.B. Klein, 8 vols (Florence: Sansoni, 1957–77) 4, 3: 544–8 for ‘battle-games’, not always at Carnival, throughout Italy.

13 A large body of scholarship now exists on late medieval Carnival, its meanings and functions. For a range of theoretical discussion see: J. Caro Baroja El carnaval; Claude Gaignebet Le Carnaval: essais de mythologie populaire (Paris: Payot, 1974); Peter Burke Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (London: Temple Smith, 1978); Mikhail Bakhtin Rabelais; Carnival! edited Thomas E. Sebeok (Approaches to Semiotics 64; Berlin and New York: Mouton, 1984); R.W. Scribner ‘Reformation, Carnival and the World Turned Upside-down’ in Popular Culture and Popular Movements in Reformation Germany (London and Roncevert: Hambledon Press, 1987) 71–101.

14 Anthony Munday The English Romayne Lyfe (1582) edited G.B. Harrison (London: Bodley Head, reprinted Edinburgh University Press, 1966) 95–7.

15 Torquato Tasso Il Gianluco overo de le maschere in Dialoghi edited Ezio Raimondi, 2 vols (Florence: Sansoni, 1958) 2: 675.

16 Bernardino Zambotto Diario ferrarese dall’anno 1476 sino al 1504 edited Guiseppe Pardi: Appendice al Diario ferrarese di autori incerti (Rerum Italicarum Scriptores 24, Part 7; Bologna: Zanichelli, 1934–36) 4 and passim. This was not strictly speaking the beginning of Carnival, but part of the New Year celebrations: the formula is si comenzo hozi andare in maschera, de licentia del duca (‘today people began to go about in masks, by permission of the Duke’).

17 Ademollo Il carnevale di Roma 141–2.

18 See chapter 8 on ‘Amorous Masking’.

19 See Cruciani Teatro nel rinascimento 204–8; Muir Civic Ritual 160–81; Canti carnascialeschi del rinascimento edited Charles Singleton (Bari: Laterza, 1936).

20 Munday English Romayne Lyfe 96–7. His contempt and incomprehension of the customs he describes make him an uncertain witness: but a similar mixture of ecumenical inclusiveness and public discrimination is seen in some Spanish cities: see Charlotte Stern The Medieval Theater in Castile (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies 156; Binghamton: SUNY Center for Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1996) 116–17.

21 These were lengths of rich material or pallia: Johanni Burckardi Liber notarum ab anno 1483 usque ad annum 1506 edited E. Celani (Rerum italicarum scriptores 32; Citta di Castello: S. Lapi, 1906) 1: 223, et passim.

22 Muir Civic Ritual 162–3, 178–9.

23 Werner Gundersheimer Ferrara: the Style of a Renaissance despotism (Princeton University Press, 1973) 200; Munday English Romayne Lyfe 90.

24 Ademollo Il carnevale 12–13.

25 Gundersheimer Ferrara 200. See also Davis ‘Reasons of Misrule’ 97–123. In 1521, Francis I of France was concussed by a piece of wood during a snowball-, egg-, and apple-fight: Martin and Guillaume du Bellay Memoires edited V.-L. Bourrilly and F. Vindry (Librairie de la Société de l’Histoire de France; Paris: Renouard, 1908) 103.

26 Thomas Platter (1574–1628) Beschriebung der Reisen durch Frankreich, Spanien, England und die Neiderlande 1595–1600 edited Rut Keiser (Basler Chroniken 9; Basel and Stuttgart: Schwabe, 1968) 121–2.

27 Burchard Liber notarum 2: 341.

28 Giorgio Vasari Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori edited R. Bettarini and P. Barocchi (Florence: Sansoni, 1976–) 4: 63–5; Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects translated A.B. Hinds, 4 vols (London: Dent, 1927) 2: 177–9; Hinds Lives 178.

29 See Francesco Cognasso L’Italia nel rinascimento 2 vols (Società e costume 5; Turin: Unione tipografico-editrice torinese, 1965) 1: 530–32.

30 Cruciani Teatro nel rinascimento 301–2; Ademollo Il carnevale 78, note 24; Grace Hart Seely Diane the Huntress: the Life and Times of Diane de Poitiers (New York and London: Appleton-century, 1936) 229. We would like to thank Dorothy Dunnett for this reference.

31 ‘Canzona delle Maschere’ in Singleton Canti carnaschialeschi 296–7.

32 Munday English Romayne Lyfe 96.

33 Giovanni Maria Cecchi (1518–87) Le Maschere e Il Samaritano in Commedie di Gio. Maria Cecchi (Firenze: Giuseppe di Giovacchino Pagani, 1818) 5, ‘Prologo’ lines 2–6.

34 For discussion of these issues see Aron Gurevich Medieval Popular Culture: Problems of Belief and Perception (Cambridge University Press, 1988); P. Spierenburg The Broken Spell: a Cultural and Anthropological History of Pre-industrial Europe (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991); Gerard Nijsten ‘Feasts and Public Spectacle: late medieval drama and performance in the Low Countries’ in The Stage as Mirror: Civic Theatre in Late Medieval Europe edited Alan Knight (Cambridge: Brewer, 1997) 107–43; Teofilo Ruiz ‘Élite and Popular Culture in Late Fifteenth-century Castilian Festivals: the Case of Jaèn’ in City and Spectacle 296–318.

35 Burchard Liber notarum 1: 183.

36 William Thomas The Historie of Italie [London, 1549] (English Experience 895; Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1977) 39v.

37 See, for example, Charles Phythian-Adams ‘Ceremony and the Citizen: The Communal Year at Coventry, 1440–1550’ in Crisis and Order in English Towns, 1500–1700 edited Peter Clark and Paul Slack (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972); Mervyn James ‘Ritual, Drama and the Social Body in the Late Medieval English Town’ Past and Present 98 (1983) 3–29; Bristol Carnival and Theater, chapter ‘The Texts of Carnival’ 59–103.

38 This, too, may be variously understood: in part it confirms the communal and harmonising interpretations that have been made of late medieval urban spectacle; yet it may equally signify the authorities’ use of the language of festival to shape their own image of the city community. See Nijsten ‘Feasts and Public Spectacle’.

39 There were odd occasions when the masquerading was forbidden because of pre-existing rioting. Ademollo Il carnevale 11–13, 141–2.

40 See e.g. Zambotto Diario ferrarese 43, 58, 71; Burchard Liber notarum 2: 266; Munday English Romayne Lyfe 96.

41 Cruciani Teatro nel rinascimento 274. Groups of young boys throwing stones at each other caused problems in Florence in carnival time, but this appears to be violence kept within a particular age group: see R.C. Trexler ‘La déraison à Florence durant la République et la Grand Duché’ in Le Charivari edited Jacques Le Goff and Jean-Claude Schmitt (Civilisation et sociétés 67; Paris: Mouton, 1981) 165–76 at 166–7. In Italy, Carnival does not seem to have been generally perceived as a particular opportunity for factional violence: see Violence and Civil Disorder in Italian Cities 1200–1500 edited Lauro Martines (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972).

42 Davis ‘Reasons of Misrule’; Ladurie Carnival in Romans; Billington Mock Kings.

43 See L.S. Van Doren ‘Revolt and Reaction in the City of Romans, Dauphiné, 1579–80’ Sixteenth-century Journal 5:1 (April 1974) 71–100; Ladurie Carnival in Romans.

44 Pierre de l’Estoile The Paris of Henry of Navarre translated Nancy Lyman Roelker (Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958) 99.

45 Tommaso Garzoni La piazza universale di tutte le professioni del mondo [1584] in Opere di Tomaso Garzoni (Venice: Valentini and Giuliani, 1617) 280: Discorso LXXXIIII.

46 Zambotto Diario ferrarese 43; Tasso Le Maschere 671; see also Old Capulet’s comments in Romeo and Juliet, Act 1, Scene 5, lines 19–38.

47 Davis ‘Reasons of Misrule’ 104–14.

48 Thomas Platter Reisen 122.

49 See also the delightful illustrations to the Alba amicorum in which the masked courtesans’ skirts can be lifted to reveal men’s breeches. J.L. Nevinson ‘Illustrations of Costume in the Alba amicorum’ Archaeologia 106 (1979) 167–76, especially 173 and plate LXXXIV(i).

50 Sixteenth-century British commentators who may or may not have understood what was happening, certainly claim that women generally did, at least sometimes, cross-dress, and there is some support from Italian observers. Fynes Moryson claims that ‘men and wemen walke the streetes in Companyes all the afternoones … having their faces masked, and the men in wemens, wemen in mens apparrell at theire pleasure’: Shakespeare’s Europe: Unpublished Chapters of Fynes Moryson’s Itinerary edited Charles Hughes (London: Sherratt and Hughes, 1903) 457; see Garzoni La piazza 280r.

51 The Merchant of Venice Act 2 Scene 6; Gl’Ingannati degli Accademici Intronati di Siena, in Commedie del cinquecento edited Nino Borsellino, 2 vols (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1962) 1: 214, Act 1, Scene 3.

52 See also Sarah Carpenter ‘Women and Carnival Masking’ Records of Early English Drama Newsletter 21:2 (1996) 9–16.

53 Roger Chartier Cultural History: Between Practices and Representations translated Lydia G. Cochrane (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988) 19–52: chapter on ‘Intellectual History and the History of Mentalités’; Ruiz ‘Elite and Popular Culture’ 309.

54 Vasari Le vite 63; Hinds Lives 177–8.

55 Zambotto Diario ferrarese 58 and passim.

56 See, for example, C.L. Barber Shakespeare’s Festive Comedy (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1959) chapters 1–3. But see Humphrey Politics of Carnival for a modified view.

57 Cecchi Le Maschere, ‘Prologo’ lines 5, 9–10.

58 Garzoni La piazza universale 280.

59 One exception might be the burlesque parade of magnifici witnessed by Sanuto in Venice in 1533: I diarii di Marino Sanuto 58 vols (Bologna: Forni, 1969–70; facsimile of Venice edition, Fedorico, 1879–1902) 57: 548. See Muir Civic Ritual 176. Nowadays such satire is one of the main features of some carnivals, especially in Spain and the New World.

60 Baldassare Castiglione Il libro del Cortegiano edited Carlo Cordié (Milan and Naples: Ricciardi, [1960]) 105–6. See Meg Twycross ‘“My Visor is Philemon’s Roof”’ in Le Théâtre et la cité dans l’Europe médiévale edited J.C. Aubailly and E. Du Bruck (Fifteenth-century Studies 13; Stuttgart: Heinz, 1988) 335–46.

61 Thomas Hoby The Book of the Courtier edited J.H. Whitfield (London: Dent, 1974) 99–100.

62 Castiglione Il Cortegiano 105; Hoby’s translation is less clear to the modern reader: ‘[if] he were in a maske. And though it were so that all menne knewe him, it skilleth not’: The Courtier 99. Castiglione then comments that it would be inappropriate for the prince to pretend to be a prince, because facendo nei giochi quel medesimo che dee far da dovero quando fosse bisogno, levaria l’autorità al vero e pareria quasi che ancor quello fosse gioco (‘[if he were to do] in sport the kind of thing he might have to do in reality, it would detract from the authority of the real thing, and make it appear that this also were a game’).

63 Platter Reisen 189; see also 373–4.

64 Platter, Thomas Journal of a Younger Brother translated and introduced Sean Jennett (London: Frederick Muller, 1963) 120; see also 224–5. This phase of the citrus crop seems to have made squashy oranges a favourite carnival missile throughout Europe. The Carnival at Binche is still throwing 200–300,000 oranges imported in a special train from Spain: see Samuel Glotz Le Carnaval de Binche (Gembloux: J. Duculot, c.1975) 17.

65 See Claude Gaignebet ‘Le Combat de Carnaval et de Carême’ Annales, economies, sociétés, civilisations 27:2 (1972) 313–45; Martine Grinberg and Samuel Kinser ‘Les Combats de Carnaval et de Carême: trajets d’une métaphore’ Annales, economies, sociétés, civilisations 38:1 (1983) 65–98.

66 1470–1520, author of the comedy La Calandria.

67 Castiglione Il Cortegiano 191–2.

68 Hoby The Courtier 174.

69 See Natalie Zemon Davis ‘The Rites of Violence’ in Society and Culture in Early Modern France (London: Duckworth, 1975) 152–88.

70 ‘Extase propinatoire de Maistre Guillaume en l’honneur de Caresme-Prenant’ in Les Joyeusetez, faceties et folastres imaginations de Caresme Prenant, Gauthier Garguille, Guillot Gorju, Roger Bontemps, Turlupin, Tabarin, Arlequin, Moulinet edited L.A. Martin, 15 vols (Paris: no publisher, 1833) 5: [6].

71 Platter Reisen 372–3.

72 Platter Journal 224.

73 B. Sastrow Social Germany in Luther’s Time: Being the memoirs of Bartholomew Sastrow translated A.D. Vandam (London: Constable, 1902) 274–5.

74 See Heers Fêtes des fous chapter 4; Persons in Groups: Social Behaviour as Identity Formation in Medieval and Renaissance Europe edited Richard Trexler (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies 36; Binghamton NY: SUNY Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1985).

75 Bakhtin Rabelais chapter on ‘Popular and Festive Forms’.

76 Nijsten ‘Feasts and Public Spectacle’; Ruiz ‘Élite and Popular Culture’.

77 Davis ‘Reasons of Misrule’; Peter Marsh ‘Identity, an Ethogenic Perspective’ in Persons in Groups 17–30.