If tournaments formed the outdoor and competitive aspect of court entertainment, the complementary indoor equivalent, based upon dancing, is broadly summed up under the term disguising.1 The two are intricately knit together: from at least the thirteenth century, descriptions of tournaments include accounts of indoor evening dance-revels as if they were part of the same event, and René d’Anjou’s Traité des tournois lays down the points where such dancing is an intrinsic part of the proceedings.2 ‘Justynges, pleys, dysguysynges’ are frequently bracketed together in contexts that suggest that they are seen as part of the same thing.3

In seeking to understand the exact nature of the indoor events we immediately encounter a problem with terminology. There is little consensus at the time on the difference between a disguising, a mummery, and a mask, though individual writers may make their own distinctions. In tracing the different patterns of entertainment, we need to look at the activity described rather than the terms used. Apart from the broad-spectrum ludus or pastime, the commonest term for what, from at least the fourteenth century, was the basic dancing entertainment seems to be disguising, which the MED first records as a form of entertainment in the early fifteenth century, although we have daunces disgisi from fifty years earlier. Disguising was partly overtaken in the early sixteenth century by mask: mummery and its analogues were also popular. For the sake of clarity in this discussion we will, rather artificially, use disguising for what seems to be the commonest root pattern of courtly masking, and mumming and mask for certain particular variants. But we should remember that this often does not correspond to the usage of the source materials.

Disguising Costume

In spite of the insecurity of the terminology, some exploration of the meaning of disguising may well help in understanding what was going on in these entertainments. We are now used to disguising as meaning ‘dressing-up to conceal one’s identity’. But although the term was sometimes used in this way in the Middle Ages, its primary sense seems to have been ‘dressing in a strange guise (fashion)’, and by extension ‘extravagant, showy, elaborate’. In moral texts disguise is associated with pride and expense:

And some putten hem to pruyde, apparailed hem þere-after,

In contenaunce of clothyng comen disgised.4

Chaucer’s Parson elaborates ‘the cost of embrowdynge, the degisé endentynge or barrynge [dagging and appliquéd stripes] … and semblable wast of clooth in vanitee’.5 Lydgate particularly identifies Germany (‘Almayne’) as an example:

… ther is non othir nacioun

Touchyng array that is so disgise

In wast of cloth and superfluite …6

Lydgate’s perception is confirmed by the popularity in later disguisings of ‘Almayn garments’, which tended to be lavishly slashed, puffed, and generally superfluous. Hall tells of a disguising in 1513 ‘with v. C. Almaines all in white, whiche was cutte so small, that it could sca[r]ce hold together’: the slashes were so close together that it was a miracle that the cloth did not rip.7 Disgisi clothes are those which make extravagant fashion statements, which may be either ‘in to muche superfluite or elles in to desordinat scantinesse’.8 New Guise (‘Latest Fashion’) in the play Mankind creates a fashionable jacket of ludicrous shortness, while Chaucer’s Parson condemns the short clothes which reveal ‘wrecched swollen membres that they shewe thurgh disgisynge’.9 A set of ‘Almain doublets’ recorded in the Revels Accounts for 1510 are described by Hall as being ‘shorte garmentes, litle beneth the poyntes’.10 Extravagance of tailoring, in whatever way, seems to be the defining ingredient. A disguising, then, seems to be a form of courtly dancing entertainment which involved dressing up in spectacular or extravagant clothes.

The delight in the sheer lavishness of apparel that accompanies disguising is inevitably bound up with important factors of wealth, power, and display. As various recent commentators point out, magnificence was a political instrument, deliberately and carefully used by monarchs and others to demonstrate and to reinforce their power.11 Magnificence was expressed through lavish expenditure and display.12 By the fifteenth century this is openly acknowledged by commentators and chroniclers. A pointed criticism of the effort to reinstate Henry VI’s prestige as monarch in 1471 was his lack of splendid apparel, ‘and evir he was shewid in a long blew goune of velvet, as though he had noo moo to chaunge with’, while the same chronicler’s one objection to the rule of Henry VII was ‘oonly avaryce The which was a blemysh to his magnyfycence’.13 In a society which overall had far fewer material goods, power and wealth were signalled by conspicuous expenditure and even a degree of careless wastefulness in personal adornment: hence the dags and slashes, puffs and overlays, and sleeves ‘that wolde cover all the body’.14 These things act as an index of prestige, recognised and formally codified in the sumptuary laws.15 There is interesting reverse evidence in an ordinance drawn up for a German Tourneying Society in 1485, which explicitly tried to restrict the lavishness of dress for the dance-revels in order not to exclude the lesser (and poorer) nobility.16 Power prestige lay very literally in the splendour of what you wore.

Conventions of historiography can give us insight here. Many fifteenth-and sixteenth-century diplomats and historians pay at least as much attention to the lavish shows we might now categorise as leisure frivolity as to more conventionally political events.17 They record costume and display minutely, concerned not only with its splendour but also with its economics. The compliment most often attached by English chroniclers to strange and impressive disguisings is that they are expensive – ‘deliver daunsinge and costly disguisings’; the Great Chronicle praises not so much the ‘straunge devysis as of the Costyous cumming Into the place’.18 The importance for the economy of such lavish display is noted, ‘what pain, labour, and diligence, the Taylers, Embrouderours, and Golde Smithes tooke, bothe to make and devise garmentes … for a suretie, more riche, nor more straunge nor more curious workes, hath not been seen’ says Hall of Henry VIII’s coronation.19 Describing the wedding procession of Katherine of Aragon in 1501, the London writer of the Great Chronicle costs the chains, needlework, and brocade in the garments of dignitaries, ‘which Cheynys & Garmentys were not estemyd of these valuys by supposayll or conjecture of mennys meyndys, but of Report of Goldsmythis & other werkmen that theym wrougth & delyverd’.20 The costs are as significant an element of the gorgeous spectacle as the appearance.

The opulent apparel of disguisings was even used as itself a form of largesse, not only demonstrating the magnificence of the wearer, but the liberality owed by him to the subject. The disguisings for the marriage of Prince Arthur to Katherine of Aragon provided:

… a meane whereof many of the kyngis Subjectis were Relevid as well ffor the stuff by theym sold & werkmanshyp of the same, as by platis, spangyllis Rosis & othyr conceytis of Sylver & ovyr gilt which fyll ffrom theyr garmentys bothe of lordys & ladyes and Gentylmen whiles they lepyd and dauncid, and were gaderid of many pore ffolkis standyng nere abowth & presyng In ffor lucre of the same.21

This may seem accidental, but clearly it was often quite intentional. At the tournament revels of 1511:

… the kyng was dysguysyd [In] a Garment of Sarcenet powderid wt Rosys and othir devysis of massy goold, The whych Garment ffor the kyng wold that It shuld be devydid among thambassadours servauntis, he commandyd the Gentylmen usshers of his Chambyr that they shuld sett the sayd servauntis at a certayn place where he shuld passe by, when the dysguysyng was endyd, and that they shuld not ffere to pull & tere the said Garment ffrom his body.22

A ‘pore sherman’ who managed to get in to the crush came away with a piece later bought by a goldsmith for £3/14/8d ‘wherby It may be concyderid, that the said Garment was of good valu’. This generosity was not confined to the commoners; Henry also publicly rewarded ambassadors with gifts of his own tournament and masking apparel.23 The king deliberately celebrated himself in his spectacular disguise as a reified emblem of magnificent liberality, giving away parts of his own performing self.

Such liberality could get out of hand. Hall records the sequel to the 1511 episode: the common people rushed to tear the clothes from the king and his company, stripping one noble ‘into his hosen and dublet’ before they were finally put back by the guard, a story which is confirmed by the lament by Richard Gibson in the Revels Accounts that it was only with ‘long labour’ that he had recovered a little of the gold decoration.24 But once the king and his companions had safely retired ‘all these hurtes were turned to laughyng and game, and [they] thought that, all that was taken away was but for honor and larges: and so this triumphe ended with myrthe and gladnes’.25 Here we have an occasion when the implicit rules of misrule were broken, the common people overstepping the invisible boundary. But once out of danger, the court could redraw it to their own satisfaction. It had only been a game, after all; they were still in honourable control and the givers of largesse. Even in disarray, the disguising is part of the apparently careless but in fact carefully calculated generosity that is required of princes.

The lavishness of the costume materials was therefore necessary, if the disguising costumes were to be not just the show but the substance of real nobility and largesse. Certainly the sumptuousness of the materials and decorations itemised in the sixteenth-century Wardrobe and Revels accounts is breathtaking. There are vast expenses in crimson velvet, blue velvet, copper tinsel of Bruges, cloth of gold and silver, ostrich feathers, silks and fine gold, sarcenet and damask. The obligation to be gorgeous in dressing the disguisings makes naturalism an irrelevance. A mask of shepherds is dressed in ‘fynne Clothe of gold and fyn Crymosyn Satten’; hermits in russet satin, black velvet and beards of damask silver; wild men in ‘grene Sylke flosshed’.26

Beneath all these resonant implications, it appears that the essence of a disguising is a ‘dressing-up’. This would account for most of the usages of the word, both in the apparently odd inclusive catalogue of ‘eny manere mommyng, pleyes, enterludes or eny other disgisynges’; or the remark ‘I saw no Disgysyngs, and but right few Pleys’ to distinguish between something that is only dressing-up and something that also includes speech or plot.27 The main focus of a disguising always seems to be the splendour and ingenuity of the costumes themselves. As Hall points out, that is what constitutes the central pleasure of the pastime: ‘This strange apparell pleased much every person’.28

Disguising Activities

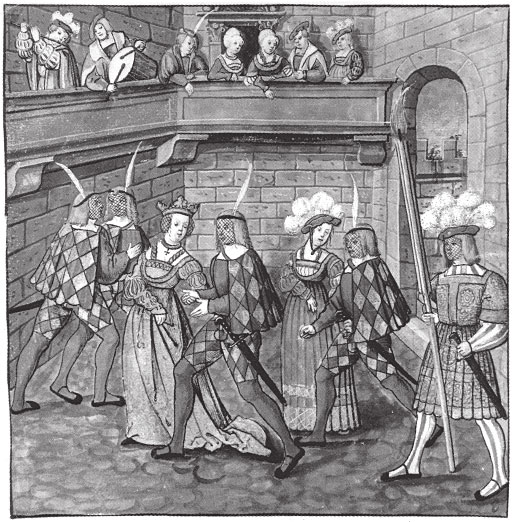

What did the disguisers do in their extravagant costumes? The chief activity at all stages seems to be dance, and richly costumed dance remains the fundamental and most popular form of the disguising right through from the thirteenth until the mid-sixteenth century. The costumes were clearly designed to enhance the spectacle of the dance. From Edward III for the next two centuries, disguisings appear to have commonly involved sets or teams of dancers in matching costumes. Edward III’s costumes came in sets of thirteen and fourteen: for the celebrations at Christmas 1347 at Guildford, for example, we find fourteen painted tunics with peacock’s eyes, fourteen tunics painted with gold and silver stars.29 The sixteenth-century disguisings very often had a team of six, but could be anything up to sixteen. The effect of the matching set apparently become so ingrained that Hall seems almost surprised to note in 1521 that ‘The French Maskers apparell was not all of one suite, but of several fashions’.30 Later in the sixteenth century the set of costumes is itself referred to as a ‘mask’ in the Revels accounts, defining the disguising by its matching clothes. The Emperor Maximilian too, using the term mummery, describes them as ‘the golden mummery’, ‘the sky-blue mummery’, or ‘a wonderful mummery of gold and silver and precious stones’. Maximilian, a direct influence on Henry VIII, was an enthusiastic patron of elaborate and spectacular disguisings: the lavish illustrations in his Freydal give a vivid impression of the visual effect of the teams of dancers in matching costume [PLATE 16].31 Even outside the royal court, Henry Machyn in 1562 records the entertainment at a wedding, ‘and after soper cam iij maskes; on was in cloth of gold, and the next maske was frers, and the iij was nunes; and after they dansyd be-tymes’.32 The matching costume sets were clearly integral to the dazzling ensemble effect of the dances.

PLATE 16: Netted maskers and ladies. Freydal of the Emperor Maximilian (1516). Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, P 5073 fol. 92.

© Reproduced by permission of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Many of the disguising costumes of Henry VIII’s court seem themselves designed to show off particularly well in dances: there are many half-and-half sets: half crimson velvet, half blue velvet with long hanging sleeves; half russet satin and half yellow satin with legs to match. Such distinctive colour blocks must have enhanced the choreography. We also find a deliberate exploitation of costume effects, as in the disguising of 1519 where the maskers wore ‘long gounes of taffeta set with flowers of gold bullion, and under that apparell cotes of blacke veluet’ embroidered, cut and puffed. During the dance the men suddenly threw off the flowing outer gowns to reveal the close-fitting black, a striking transformation.33 The dances are often described in terms that emphasise the combined aesthetic effect of costume and movement. The Great Chronicle records a disguising of 1493 of:

… xij Gentyllmen ledyng by kerchyffys of plesance xij ladyys beyng all Costiously & goodly dysguysid … The whych Gentylmen lepid & daunsid all the length of the halle as they cam, and the [ladies] slode aftyr theym as they hadd standyn upon a fframe Runnyng, wt whelys, They kept theyr Tracis soo demwyr & cloos that theyr lymmys movid all at oonys … It was wondyrfull to behold the excedyng lepys Ganbawdys & turnyngys above ground which the Gentylmen made that theyr spangyls of goold & othyr of theyr Garnysshys ffyll ffrom theym Rygth habundantly, But Evyrmore the ladyes kept theyr ffirst maner soo demuyrly as they hadd been Imagis.34

These are clearly exhibition dances designed for spectators.

During the fifteenth century, the dance format might be much elaborated with processional entries, pageant vehicles, and allegorical frames.35 The court of Burgundy led the way in extravagant spectacle and was avidly copied.36 In 1501 at the celebrations for the marriage of Prince Arthur and Katherine of Aragon, we find what seems to be the first instance in Britain of spectacular pageant cars used to transport the disguisers into the hall to dance.37 On one evening the court ‘beheld an interlude till the disguysyng cam in, the which disguising was shewed by ij pagents’. Two cars entered, one like a garden, the second:

… made rounde, aftir the fachyon of a lanterne, cast owte with many proper and goodly wyndowes fenestrid with fyne lawne, wherein were more than an hundred great lightes, in the which lanterne were xij goodly ladies, disguysid, and right rychely beseen.38

This shadow show was clearly dazzling, and such entries were repeated and developed for the next fifty years. But the wonderful pageants were effectively an adjunct to the traditional form: descending from them the disguisers ‘dauncyd a long space, dyvers and many daunces’. Even when the pageant vehicles came to be involved in allegorical scenarios – an assault on a castle by Knights of the Mount of Love, or a garden of pleasure inhabited by allegorical knights of the Queen Noble Renomé – they remained fundamentally a framework for the costumed dances.39 The pageantry acts as an enhancement of the ‘dressing-up’ involved in disguising. The pageant cars were created, like the costumes, to be admired and wondered at, ‘such tyme as it came bifore the Kynge it was turnyd rownde abought in the settyng downe of hit, so as the Kynge, the Quene, and all thestates might see and behold thorughowtly the proporcion thereof’.40 Even at its most elaborate the disguising remained at root an entry of magnificently dressed dancers.

Disguising Masks

If the central features of a disguising are the extravagance of the costumes and the dancing spectacle, where does this leave the role of masks? The wearing of masks is not in itself a necessary part of such dressing-up. The fourteenth-century daunces disgisi which the MED glosses as ‘of a dance? masked’ is more likely to mean simply ‘dressed-up dances’. Nonetheless masks do seem to have been a feature of disguisings from very early on. The Wardrobe Accounts for Edward III in the mid-fourteenth century confirm a widespread and lavish use of masks for what are most probably daunces disgisi. For the Christmas celebrations at Guildford in 1347 the Wardrobe supplied large numbers of masks (viseres), crests, and ‘heads’: fourteen masks of women’s faces, fourteen of bearded men, fourteen silver angels’ heads, fourteen swans’ heads, fourteen dragons’ heads, fourteen peacocks’ heads. Some of these masks are paired with ‘straunge apparell’, the swans’ heads with ‘painted white tunics’ and wings, the peacocks with wings and tunics painted with peacocks’ eyes, the angels perhaps with the ‘tunics painted with gold and silver stars’.41 The following year’s Christmas festivities at Otford offer even more extravagant masks: ‘heads of men with lions’ heads’ or ‘elephants’ heads’ or ‘bats’ wings’ above, heads of wodewoses and others, are all supplied ad faciendum ludos Regis.42 There is some debate over whether these costumes and headgear are primarily for tournaments or indoor revels: apart from the contemporary blurring together of the two spectacles, both viseres and crestes are terms that might apply to helmets as well as to masks. But the context seems to suggest that they are the costumes for disguisings.43 Masks, in large quantities, were often provided at the time of tournaments: 288 for dukes, ladies, and damsels at Lichfield, 44 for the king, nobles, knights, and ladies at Canterbury, both in 1348.44 But the status and sex of the wearers and the enormous quantities suggest that these belonged not to the jousting itself but either to the evening disguisings or to the masked processions which sometimes preceded a tournament. Certainly, later development of the disguising suggests that the matching sets of fantastic costumes and masks provided for Christmas activities belong to indoor dancing revels.

If Edward III’s Wardrobe records strongly suggest an association of masks with disguisings, by the time of the better documented accounts of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries masks seem an almost obligatory part of disguising costume. Hall’s detailed accounts are paradoxically often imprecise, as he assumes his readers’ familiarity with the conventions; but it is clear that most of the disguisings he describes do involve masks. Sometimes they are simply recorded as a normal part of the spectacular costumes: ‘with robbes and longe tippettes to the same of blew Damaske visarde’, ‘their bonettes of whyte velvet, wrapped in flat golde of Damaske, with visers and white plumes’.45 But often the costume descriptions make no reference to masks, and it is only when we are told that they are taken off at the end of the dancing that we find the disguising has involved them. It may be that Hall so fully assumes that disguising gear includes masks that he has no need to specify them. But his occasional comment that ‘all these yong lorde[s] had visers on their faces’ or ‘all with visers’ possibly suggests that on some occasions masks were not worn.46

Financial records and inventories from early in the sixteenth century suggest that disguising costumes almost automatically included masks. The inventory of the Lisle family’s moveables in Calais in 1540 includes:

Item xii maskyn gownes with hoodes & capps of bokeram Item a dossen of maskyng Vysardes.47

Clearly the two belong together. Similarly the Revels Office’s notes of sets of disguising costumes tend to include masks as part of the set: ‘with vj hattes answerable & vizardes’.48 The overwhelming impression is that disguisings generally, as a matter of course, were masked.

Various reasons for the use of masks in disguisings suggest themselves. In the revels of Edward III and some of the disguisings of the Emperor Maximilian, or Henry VIII and Edward VI, the wonderful costumes dress the wearers up ‘as’ something. The peacocks, angels, and wodewoses of the fourteenth-century revels are obvious; what is more common in the sixteenth century is a dressing-up in the clothes of another country or another time. Maximilian’s disguisings feature many costumes of ‘the antique fashion’; Edward III’s tournament of Tartars in 1331 exemplifies an interest in national and exotic costume that burgeons in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with the publication of printed costume books. Reports of Henry VIII’s disguisings are full of costumes ‘cut like Almaynes’, ‘like to the Portingal slopys’ or ‘after the fashion of Savoy’, ‘after ye fassion of Inde’, ‘tired like to the Egipcians very richely’.49 A fine example is the Shrove Sunday disguising of 1510 in which the dancers entered in pairs: the king and his partner ‘after Turkey fasshion’, the following pair ‘after the fashion of Russia’, then a pair ‘after the fashion of Prussia’ with the torchbearers ‘lyke Moreskoes, their faces blacke’.50 It is not unlikely that these national costumes were linked to the performance of national dances. Jean d’Auton reports a feast in 1501 at the court of Louis XII at which there were branles in the styles of France, Germany, Spain, Lombardy, and Poitou, with each group of dancers dressed in the fashion of the country in whose style they were dancing,51 and Arbeau suggests several times that a popular dance was originally created for a Turkish or Moorish masquerade.52 Lucres’ ‘basse dance after the guise of Spain’ may well have had the dancers dressed as Spaniards.53

Some of the mask-makers’ products are designer fantasies. Edward III’s designed weird visors of ‘men with elephants’ heads above’ and ‘men with bats’ wings’; two hundred years later Edward VI was entertained with disguisings of bagpipes, cats, and the famous ‘medyoxs half man half death’.54 With all the representational costumes, and especially with these fantasies, the mask is a natural completion of the costume. The disguisers ‘become’ something else and the mask removes the distraction of the familiar face to enhance that other. This is what we find with the group of maskers at the Field of Cloth of Gold, dressed in gowns ‘of the auncient fashion’, decorated with the motto ‘adieu Iunesse, farewell youth … with visers, their faces of like auncientie’.55 It is less clear whether the national costumes were given appropriate masks, though the more exotic ones clearly were: Edward III had Tartar masks, and ‘fyne Turkes vizardes’ are mentioned in Elizabeth’s Revels accounts for 1572,56 while in one of the first disguisings of Henry VIII’s reign two ladies in head-dresses ‘lyke the Egypcians’ had:

… their faces, neckes, armes & handes, covered with fyne pleasaunce blacke: Some call it Lumberdynes, which is merveylous thine, so that thesame ladies semed to be nygrost or blacke Mores.57

Most disguising clothes, however, seem to be extravagant and ‘straunge’, without representing anything in particular. We cannot be sure exactly what the masks for such costumes were like, but the huge quantities bought might suggest that at least some versions were fairly standardised. The Revels inventory for the first year alone of Edward VI’s reign includes 24 dozen ‘vezars or maskes for men & women newe & Servysable with Berdes & without Berdes’ (plus another ‘vij vezars for Allmayne with Berdes of damaske golde’ which are classified as ‘not servisable’).58 Masks are bought in bulk from the ‘milliner’ or ‘haberdasher’:

1511 |

24 visors at 2s ‘Bought of Bartyllmewe, the haberdasher’59 |

1551 |

‘Christofer milliner for iij dozen fyne visars at xxxvjs viijd dozen’60 |

We might assume these masks to be something like the simple black domino now generally associated with masked balls and harlequinades; some illustrations, though not from Britain, do suggest half-masks rather resembling the later commedia dell’arte. But it appears that at least some of the bulk consignments were full ‘real’ faces, as suggested by the ‘viij visers ayenst this night of the worst and well favourest make’.61 Related calendar illustrations by Simon Bening give an impression of such masks [PLATES 17 and 19].62 They represent the entry of a relatively simple disguising in a noble household. The central figure in each picture might appear to be bare-faced, but closer examination shows he is wearing a ‘well-favoured’ mask: the line of the edge of the mask is visible around his jaw and in front of the ear, and the mask is painted in a slightly darker and more monochrome flesh colour than his neck or the faces of the unmasked musicians. The figure on the extreme left is also masked, showing slightly coarser features than the unmasked faces, and cut-out eye-holes. In the Munich manuscript, the group of women in matching costumes on the right show the same slightly blank and stylised faces. These ‘real-face’ masks can make it difficult in illustrations, as in the written accounts, to see whether figures are masked or not: clues are the tell-tale eye-holes and sometimes differences in colour.63

Such real-face visors raise intriguing questions about the purpose of the masks. As the calendar illustrations show, they seem to be masks that play down their own status: they are hardly visible as masks at all. Of course this would not be the case during performance as, however realistic, the impassivity of the mask is unmistakable. But since they appear not to embody any particular fantasy or identity their role is presumably simply to conceal the face beneath: to cover the known face without either making a feature of that concealment, or activating a response to a new persona. Nonetheless they must have been felt to make an important contribution to the purpose and pleasures of the disguising. They are, perhaps, a sixteenth-century equivalent of the modern ‘neutral mask’, active in performance, but imposing no particular role on the performer.64 They inevitably draw attention to the disguisers’ otherness: the costume is gloriously strange, the mask enhances both the splendour and the strangeness.

Apart from questions of representation, there is a dynamic advantage to masking in an activity which calls so much attention to costume. Normal focus on the human face as a source of information is denied, diverting attention onto the rest of the body, its wonderful garments, and overall body language and movement. This may well also inform the link between masks language and movement. This may well also inform the link between masks and dancing. The masks contribute to the costume while focusing attention on the movement; this can only have been enhanced by the matching sets of masks. Not only does the individualising and eye-drawing face of the dancer disappear, but the disguising presents a set of identical still mask-faces. A fairly common variation on the plain-face masks is the caul or netted mask, popular at the court of Maximilian and widely illustrated, where a net, sometimes decorated or spangled, half-conceals the face [PLATE 16]. This seems similarly to reduce separate identity to an overall still-sameness without imposing a new identity or even perhaps entirely obliterating the face beneath.65 Such matching masks, of whatever style, foreground even more the aesthetic patterning of the dance, encouraging a focus on the whole more than its parts.

PLATE 17: A disguising with ‘real-face’ masks. Book of Hours (the ‘Golf Book’) with illustrations by Simon Bening (c. 1500). Calendar illustration for the month of February. London: British Library, Additional MS 24098 fol. 19v.

© Reproduced by permission of the British Library.

Although the spectacle of costumed dancing seems an end in itself for most disguisings, the strangeness of costumes and masks perhaps inevitably makes more complex semantic implications possible. This is very clear in a set of apparently straightforward disguisings that we find in a different and more legible context, inset into the late-fifteenth-century play of Wisdom.66 At one point in the action, the three faculties of the Soul, perverted to the vices of Maintenance, Perjury and Lechery, propose to:

make a dance

Off thow that longe to owr retenance

Cummynge in by contenance.67

Three teams of masked disguisers enter to dance. The followers of Maintenance are ‘disgysyde … with rede berdys, and lyouns rampaunt on here crestys’; Perjury’s dancers are clothed as corrupt jurors wearing ‘hattys of meyntenaunce’ and Vyseryde dyversly’; while Lechery’s final team appears to confirm the presence, unusual in drama, of female performers, some in male dress: ‘Six women in sut, thre dysgysyde as galontys and thre as matrones, wyth wondyrfull vysurs congruent’.68 Disguisings, in which women often took part, were apparently seen as offering a safer performing space than the drama proper.

Wisdom’s teams of dancers perform entirely traditional disguisings; but they also overtly develop the moral issues of the play and may make more specific political comment. The spectacular costumes carry explicit visual meanings for the audience within the context of the play. The red beards and lion crests of Maintenance’s dancers signify not only general qualities of wrath and pride, but specifically allude to the political reputation of the local magnates, the Suffolks.69 The ‘diverse’ visors of Perjury’s team may simply suggest non-matching masks; but they are generally taken as a masking realisation of their leader’s comment ‘Jurowrs in on hoode beer to facys’: this common emblem of ‘double-faced’ treachery was portrayed on-stage and off as a two-faced mask.70 We are able to read these meanings because of the narrative context of the play, the expository speeches of the Three Faculties, and the explicit symbolism of the costumes. For most disguisings we do not have access to such an enabling context and consequently can only guess whether the form expressed meanings beyond performed magnificence. But occasional examples of similar court entertainments suggest that the disguising could be not just a powerful aesthetic spectacle but a particular and topical form. Sometimes this is fairly simple: in a disguising of 1510 in the Queen’s chamber to entertain the ambassadors of the Emperor Maximilian and of Spain, the male dancers were dressed ‘in Almayne Iackettes’ while the women’s costumes were ‘strynged after the facion of Spaygne’, the disguising clothes clearly honouring the ambassadors’ nations.71 In the more elaborate versions of disguising that proliferated during the sixteenth century, explored in the next chapter, we sometimes find a fuller degree of semantic complexity.72

Disguising Performers

The disguising masks’ effect on the spectators is tied to another central issue. This is the question of who masked, what relationship the maskers held to the spectators, and whether at any stage their identities were revealed. These factors all affect the meaning of these performances.73 Although early records are not very detailed, the central activity of the disguising appears always to have involved the nobility of the court, both men and women. Professional performers, often drawn from the Chapel, were clearly involved with some of the elaborated frameworks of later disguisings, song, debate, and dramatised pageant; but the core element of spectacular dance belonged to the court itself. The earliest dance revels that accompany tournaments are recorded as involving the participants rather than entertainers, and the basic pattern seems to follow that recorded in 1489 of a jousting held to honour an English embassy to Portugal et apres … dancerent les dames aveques les justeurs, les quellz estoint bien richement abilliés et disguissés (‘and afterwards the ladies danced with the jousters, who were very richly dressed and disguised’).74 The quantities of masks and costumes created for Edward III’s revels equally suggests that it was the members of court who performed in disguisings. Although the multiple sets of peacocks, angels, or wodewoses could conceivably have been worn by shifts of employed performers, the hundreds of masks used at Lichfield in 1348 are specifically for ducibus dominabus et domicellis (‘dukes, ladies, and damsels’) and were given to them afterwards.75 Later, more detailed, records confirm that the disguisings are performed by ‘lordys & ladyes and Gentylmen’, ‘lordes, knightes, and men of honour, moost semely and straunge disguysid’.76 Disguisings, then, are performed by people socially equal and probably known to the spectators, part of their own circle. Those watching would know that the person behind the mask was ‘one of us’ even if they could not see the face. As far as evidence survives, little seems to have been made of this in its earlier stages. We do not know whether the maskers made any play with their identity, but there is nothing to suggest any significant consciousness of the familiar face behind the concealing mask during the performance. Disguisers and spectators do, however, stand in an interestingly flat relationship to each other, since it is only the mask – not role, class, or profession – that divides performer from audience.

This is very clear in the famous account of a disguising at the court of France in 1392, recorded by the chronicler Jean Froissart because it led to a disaster. A winter wedding77 between two young courtiers was being celebrated with a great supper and dancing, attended by the royal family. As the midnight pièce de resistance of the evening’s entertainments, a squire from Normandy arranged for a disguising for six dancers, of whom the King was one. They were to be hommes sauvages, ‘wild men’, in English woodwoses:

… il fist pourveir six cottes de toille … puis semer sus délyé78 lin en fourme et en couleur de cheveuls … Quant ils furent tous six vestus de ces cottes qui estoient faittes à leur point et ils furent dedens enjoinds et cousus, ils se monstroient à estre hommes sauvages, car ils estoient tous chargiés de poil du chief jusques à la plante du piet.79

He devysed syxe cotes made of lynen clothe, covered with pytche, and theron flaxe lyke heare … And whan they were thus arayed in these sayd cotes, and sowed fast in them, they semed lyke wylde wodehouses full of heare fro the toppe of the heed to the sowle of the foote.80

While they were changing, one of the dancers expressed serious qualms about the fire hazard, and a message was sent to the dancing-chamber that all torches were to move back to the walls, well away from the disguising.

The King came first, presenter to the troupe: the other five were all tied together. However, he deserted the rest, and went to show himself off to the ladies on the dais ainsi que jeunesse portoit (‘as youthe requyred’). His young aunt, the Duchess de Berri, par esbatement (‘in fun’), seized him by the arm,

… et voult savoir qui il estoit. Le roy estant devant elle ne se vouloit nommer. Adont dist la duchesse de Berry: “Vous ne m’eschapperés point, ains que je sache premiers vostre nom.”81

… to knowe what he was, but the kyng wolde nat shewe his name. Than the duches sayd: Ye shall nat escape me tyll I knowe your name.82

It seems strange that having entered as part of a dancing troupe, the king should then leave it to tease the ladies; ‘as youthe requyred’ suggests that he was, fortunately as it turned out, behaving irresponsibly. Charles VI was in his early twenties; his dancing companions were of an age; the Duchess, though his aunt-in-law, was only fifteen. Her presence of mind was however invaluable in the next few minutes. The king’s brother, the Duke of Orleans, coming in late with his own torchbearers, had not heard the warning. Wanting to know who the disguisers were, he seized a torch and held it so close that it caught the flax, and

… tantost il est enflamé. La flamme du feu eschauffa la poix à quoy le lin estoit attachié à la toille. Les chemises linées et poyés estoient sèches et déliés et joindans à la char et se prindrent au feu à ardoir, et ceulx qui vestus les avoient et qui l’angoisse sentoient, commencièrent à crier moult amèrement et horriblement.83

… sodaynly [it] was on a bright flame, and so eche of them set fyre on other; the pytche was so fastened to the lynen clothe, and their shyrtes so drye and fyne, and so joynynge to their flesshe, that they began to brenne and to cry for helpe.84

Would-be rescuers were seared by the flaming pitch. One dancer broke away and threw himself into a barrel of washing-up water in the pantry: he survived, hideously burned. The King was saved by the quick reactions of the Duchess, who protected him from sparks by rolling him up in the train of her dress. The other four died there and then, or on the following day. The event was known thereafter as Le Bal des Ardents.85

The illustration in PLATE 18, though painted some seventy years later, is by someone clearly used to this kind of entertainment and well able to imagine the disaster. It recreates the scene atmospherically: the shadows cast by the torches, the flames leaping through the hemp, the panic enhanced by the expressionless mask faces with their cavernous eyes, and the desperate gestures. The full horror clearly arose from the identity of the dancers, their relationship with the spectators, and, probably, the hideous irony of the scenario. The Queen, knowing that the King was to be one of the maskers, collapsed; one of the burning dancers crioit à haults cris: ‘Sauvés le royl sauvés le roy!’ (‘cryed ever with a loude voyce: Save the kynge, save the kynge’). But besides this, the masking as hommes sauvages was to give the king and his youthful courtiers the licence to behave for the space of the evening like uncivilised and unrestrained children of nature:86 a liberating disguise for young men who normally conducted their lives within the cramped framework of court etiquette. Wild men had notoriously unbridled physical appetites, and one wonders how far the King was playing at this when he went over to the ladies. The fifteen-year-old Duchess seems to have responded with enthusiasm, even to physically laying hands on the anonymous stranger. But, ironically, Charles was already mentally unstable, and had the previous summer had a dangerously violent episode in which he tried to kill his brother the Duke. Froissart consciously parallels his case with that of Nebuchadnezzar, the king who in medieval eyes became a wild man, covered with hair and without reason.87

PLATE 18: The Bal des Ardents. The chained dancers are on fire in the right foreground; the King, behind them to the left, is wrapped in the Duchesse de Berri’s ample train. One dancer escapes to the kitchens; the Queen, centre under dais, wrings her hands; the figure with a torch on the right under the minstrels’ gallery is presumably the Duc d’Orléans. Froissart Chroniques: Ghent/Bruges (c. 1470). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, MS fonds français 2646 fol. 176r.

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris/Bridgeman Art Library.

The first-reported public reaction to the tragedy was that it was a warning from God to the king que il se retraist de ses huiseuses et que trop en faisoit et en avoit fait par cy-devant, lesquelles n’appartenoient point à faire à ung roy de France, et que trop jeunement se maintenoit et estoit maintenu jusques ad ce jour (‘to withdraw himself from such young idle wantonness, which he had used overmuch, being a king’).88 On the human level, the youthful heedlessness of the participants was held responsible. Froissart explicitly exculpates the Duke of Orleans, blaming it on his jeunesse et … ygnorance (‘youth and ignorance’), but the political situation was volatile, and English chroniclers were soon accusing the Duke of attempted assassination.89

Though at least two of the spectators actively tried to discover the identity of the stranger behind the wild-man mask, it does not seem to have been the specific focus of the entertainment. In early-sixteenth-century England this changed, possibly under the personal influence of Henry VIII. At the beginning of his reign Henry was only eighteen and ostentatiously good at dancing, singing, and composing as well as jousting. He had danced publicly at court revels in his father’s time, clearly enjoyed performing, and did not stop doing so once he was crowned.90 In the first year of his reign we find him at a banquet where he ‘withdrew hym selfe sodenly out of the place’ returning with five other lords:

… apparayled all in one sewte of shorte garmentes, litle beneth the poyntes, of blew Velvet and Crymosyne with long sleves, all cut and lyned with clothe of golde … on their heades bonets of Damaske, sylver flatte woven in the stole, and thereupon wrought with gold, and ryche fethers in them, all with visers.91

The king’s set danced with six disguised ladies (‘the lady Mary, syster unto the kyng was one, the other I name not’) and then withdrew. This is the first clear instance of a developing pattern. The disguising takes its normal form, but the identity of the matching maskers, in particular the identity of the king, becomes a central part of the dynamic of performance. This disguising was important because of who took part in it.

Initially it may seem that the effect of the disguising is to make the king anonymous, first by putting on a mask, and then by appearing as one of an identically dressed team. Efforts were clearly made to uphold this fiction, as shown in a famous anecdote by the visiting Venetian Gasparo Spinelli about a disguising in 1527 when the maskers were all dressed in baggy black velvet slippers because the king, having hurt his foot playing tennis, was unable to wear shoes.92 In theory this produces a delightful social levelling as the king makes himself neither more nor less important than his companions. But, as seen in the tournaments, the disguises of these courtly entertainments are double-edged. If Henry is masked, it is in order to demonstrate the real grace and splendour of his dancing performance, to prove his own capacity. He actually needs to be recognised, concealing his identity only in order to confirm it. As Castiglione explains,

… in tal caso, spogliandosi il principe la persona di principe e mescolandosi egualmente con i minori di sé, ben però di modo che possa esser conosciuto, col rifutare la grandezza piglia un’altra maggior grandezza, che è il voler avanzar gli altri non d’autorità ma di virtù.93

… in this point the prince stripping himselfe of the person of a prince, and mingling him selfe equally with his underlinges (yet in such wise that hee may bee known) with refusing superioritie, let him chalenge a greater superioritie, namely, to passe other men, not in authoritie, but in vertue.94

Consequently the person of the king must at some point, in some way, be seen through the mask. This is what we find when we look closely at Henry VIII’s disguisings. Study of Richard Gibson’s Revels accounts suggests that although the king was indeed costumed like his companions, there were subtle differences.95 As in the 1511 tournament, his costume was the same but more so: in a set of six Almains whose hose are sewn with pomegranates of gold, Henry has twenty-one pomegranates, the next best twenty, the third seventeen, the fourth sixteen, the fifth and sixth fourteen each. Or the king and his masking partner have two-shilling feathers, the next pair sixteen-penny feathers and the third one-shilling feathers.96 Marking the distinction was clearly important.

More significant, perhaps, is that Hall suddenly begins to record that the disguisers unmask at the end of the dancing. We have no way of knowing whether this was ever the case with fourteenth-and fifteenth-century maskers, but it was clearly felt to be a significant part of Henry’s entertainment. Time and again Hall concludes his descriptions with ‘after they had daunced, they put of their viziers, & then they were all knowen’.97 He implies that the moment of unmasking was a moment of delighted pleasure that identity had been revealed, though above all it is the identity of the king that is at stake. Spectators typically ‘hartely thanked the kyng, that it pleased him to visit them with such disport’. The unmasking is interpreted as a sign of the king’s gracious generosity, his identity a gift to his courtiers. This discovery apparently becomes a crucial part of the performance.

In this unmasking the dynamic relationship between the mask and the hidden face is foregrounded: there is a conscious play with identity that seems characteristic of the beginning of the early-modern period.98 This playful flirtation with masking in courtly disguising games can be seen even more prominently in the variations on the basic pattern that we find in the English court of the early sixteenth century.

Notes

1 Anglo ‘Evolution of the Early Tudor Disguising’ 3–44.

2 See e.g. Le Tournoi de Chauvency edited M. Delbouille (Liège; Paris, 1932); R.S. Loomis ‘Edward I: Arthurian Enthusiast’; René d’Anjou Traitie de la forme et devis d’un tournoi 39, 47, 58. The illustrations of the Freydal of the Emperor Maximilian are arranged in groups of four: three jousts and one mummery per day. See chapter 5 on ‘Tournaments’ note 73.

3 MED sv disgising. This may even inform the apparently surprising confusion between chroniclers as to whether the conspiracy against Henry IV in 1400 involved a ‘mumming’ or a ‘joust’. These were not such different occasions as later readers may assume. See chapter 4 on ‘Mumming’ notes 42, 43.

4 Piers Plowman B. Text, Prologue lines 23–4.

5 Chaucer The Parson’s Tale in The Riverside Chaucer edited Larry D. Benson (Oxford University Press, 1988) line 416, page 300.

6 John Lydgate Fall of Princes: part III edited Henry Bergen EETS ES 123 (1924) 746; Book 6, lines 2677–9.

7 Hall Union 527. Cornelius in Henry Medwall’s Fulgens and Lucres dresses up to impress ‘like to a rutter somewhat according’: The Plays of Henry Medwall edited Alan H. Nelson (Tudor Interludes; Cambridge: Brewer, 1980) 49; part 1, line 718.

8 Parson’s Tale page 300, line 413.

9 Mankind in The Macro Plays edited Mark Eccles EETS 262 (1969) 175; lines 671–718; Parson’s Tale line 426, page 301.

10 Brewer Letters and Papers 2:2 1492–3; Hall Union 513–14.

11 This issue is much discussed in Anglo Spectacle, Pageantry and Early Tudor Policy; Kipling Triumph of Honour; Roy Strong Art and Power: Renaissance Festivals 1450–1650 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1984); John Scattergood ‘Skelton’s Magnyfycence and the Tudor Royal Household’ Medieval English Theatre 15 (1993) 21–48.

12 See e.g. the definitions of royal magnificence offered at the beginning of the Black Book of Edward IV in The Household of Edward IV: the Black Book and the Ordinance of 1478 edited A.R. Myers (Manchester University Press, 1959) 86.

13 Great Chronicle 215, 339.

14 Fulgens and Lucres Part 1 line 748. Cornelius’ gowns are ‘new and straunge For non of them passith the mid thy’ (lines 738–9).

15 Frances Baldwin Sumptuary Legislation and Personal Regulation in England (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1926); see Sponsler Drama and Resistance chapter 1, 1–23.

16 Jackson ‘Tournament and Chivalry’ 52–5.

17 See, for England the Great Chronicle and Hall Union. European parallels include Hechos del Condestable Don Miguel Lucas de Iranzo (cronica del siglo XV) edited Juan de Matas Carriazo (Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 1940); Olivier de la Marche Mémoires edited H. Beaune and J. d’Arbaumont, 3 vols (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1883–88). See also Streitberger Court Revels 6.

18 Hall Union 494; Great Chronicle 254.

19 Hall Union 507.

20 Great Chronicle 311.

21 Great Chronicle 315.

22 Great Chronicle 374.

23 See the running at the ring before the Spanish ambassadors in 1509, or the disguisings of 1527: Hall Union 514, 724.

24 Kew: Public Record Office E 36/217 fol. 68: ‘memo þat þe kyngys apparell and master sir thomas knevetys apparell was lost and spent and spoylyd soo þat wyth þe los of thees xiiij letterys to þe Summa fvllly [sic] ccxxv ovncys of golld … restoryd and delyveryd by me rechard gybson after long labvr to get þe iiij garmentys and bonetys and hossys of þe loordys In lettyrys \of golld/to Robard a madas vc xv’ It would seem that the maskers also went off with some gold letters.

25 Hall Union 519.

26 George Cavendish The Life and Death of Cardinal Wolsey edited R.S. Sylvester EETS 243 (1959) 25; Hall Union 568, 517.

27 Guildhall Letter Book I, fol. 223r; from a herald’s account of Christmas festivity 1489, British Library Cotton MS Julius B XII, fol. 64, printed John Leland De Rebus Britannicis Collectanea 6 vols (London: G. and J. Richardson, 1770) 4: 256.

28 Hall Union 580.

29 Vale Edward III and Chivalry 69–71, 175.

30 Hall Union 619.

31 Freydal Des Kaisers Maximilian: see chapter 5 on ‘Tournaments’ note 73.

32 Diary of Henry Machyn 288.

33 Hall Union 597.

34 Great Chronicle 251–2.

35 Anglo ‘Early Tudor Disguising’ 3–44; Kipling Triumph of Honour 96–115.

36 Kipling Triumph of Honour chapter 5. See, for reports, de la Marche Mémoires; Mathieu de Coussy (d’Escouchy) Chroniques edited Jean Alexandre Buchon (Collection des chroniques nationales françaises écrites en langue vulgaire du 13e au 16e siècle, 12–15; Paris: Verdière, 1825–28), etc.

37 Anglo Spectacle, Pageantry 100–103; Kipling Triumph of Honour 102–15.

38 The Receyt of the Lady Kateryne edited Gordon Kipling EETS 296 (1990) 60. See also Kipling Triumph of Honour 105–9.

39 Kipling Receyt 56–7; Hall Union 518–19.

40 Kipling Receyt 59–60.

41 Nicolas ‘Garter’ 37–8.

42 Nicolas ‘Garter’ 43.

43 See Vale Edward III and Chivalry 69–71; Wickham Early English Stages 1: 188–9.

44 Nicolas ‘Garter’ 29–30, 39; Vale Edward III and Chivalry 70.

45 Hall Union 513, 516.

46 Hall Union 613, 514.

47 The Lisle Letters edited Muriel St. Clare Byrne, 6 vols (University of Chicago Press, 1981) 6: 201.

48 Documents relating to the Office of the Revels in the time of Queen Elizabeth edited A. Feuillerat (Materialien zur Kunde des älteren Englischen Dramas 21; Louvain: A Uystpruyst, 1908; reprinted Liechtenstein: Kraus, 1968) 146.

49 Hall Union 516, 580, 595, 597.

50 Hall Union 513.

51 Jean d’Auton Chroniques de Louis XII edited R. de Maulde de la Clavière, 4 vols (Société de l’Histoire de France; Paris: Renouard, 1891) 2: 100.

52 Thoinot Arbeau Orchésographie (Langres: Jehan des Preyz, 1588) 82r.

53 Fulgens and Lucres Part 2, lines 380–81. The most famous basse-danse base is called La Spagna; there is also one called Beauté de Castille. The arrival of Katherine of Aragon in her Spanish dress had caused great interest: Kipling Receyt 57, 67: Bernard André Historia regis Henrici Septimi: a Bernardo Andrea tholostate conscripta, necnon alia quaedam ad eundem regem spectantia edited James Gairdner Rolls Series 10 (1858) 288.

54 Nicolas ‘Garter’ 37; Feuillerat Edward VI and Mary 130–31, 145. Mediox seems to be a version of the Latin adjective medioximus ‘intermediate, halfway’. It has been suggested that these disguisings were specially designed to appeal to an adolescent king.

55 Hall Union 613.

56 Feuillerat Elizabeth 158.

57 Hall Union 514.

58 Feuillerat Edward VI and Mary 14.

59 Brewer Letters and Papers 2.2 1493.

60 Feuillerat Edward VI and Mary 49.

61 Feuillerat Edward VI and Mary 92.

62 British Library Additional MS 24098; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Clm 23638.

63 Illustrations of the Schembart Carnival at Nuremberg (e.g. Oxford: Bodleian Library MS Douce 346; British Library Additional MS 15707) equally appear to show guisers with bare faces, until a sequence in which they are suddenly coloured blue and it becomes that clear they are masks. Conspicuous eyeholes are also shown in the masks of the Breughel Carnival and Lent.

64 See Jacques Lecoq ‘Rôle du masque dans la formation de l’acteur’ in Le Masque: du rite au théâtre edited Odetta Aslan and Denis Bablet (Paris: CNRS, 1988) 265–9; and ‘Le masque neutre’ in Le Corps poetique 47–56. Alberto Marcia The Commedia dell’Arte and the Masks of Amleto and Donato Sartori (Florence: La Casa Usher, 1980) [5] and plates 6 (Lecoq holding a neutral mask), 15, 156–7. With the lapse of time, these masks look less ‘neutral’ than they were thought to be by their creators.

65 Effectively, spangles (sequins) confuse the eye, which is attracted to the sparks of light and is unable to refocus on the face beneath the mesh.

66 Wisdom in The Macro Plays edited Mark Eccles EETS 262 (1969). On the disguisings see John Marshall ‘The Satirising of the Suffolks in Wisdom’; ‘Her Virgynes, as Many as a Man Wylle: Dance and Provenance in Three Late Medieval Plays’ Leeds Studies in English NS 25 (1994) 111–148. The ready acceptance of disguising in household drama is clear, as shown in the casual comment in the cast list of Rastell’s interlude Four Elements which suggests ‘Also yf ye lyst ye may brynge in a disgysynge’: John Rastell The Nature of the Four Elements in Three Rastell Plays edited Richard Axton (Cambridge: Brewer, 1979) lines xi-xii.

67 Wisdom lines 685–7.

68 Wisdom lines 692, 724, 752. Congruent, i.e. suitable to the costume, is the usual reading for the MS conregent.

The presence of these female performers would equally add weight to the argument that Wisdom was designed for performance in a great household: Westfall Patrons and Performance 102.

69 See Marshall ‘The Satirising of the Suffolks’.

70 See chapter 10 on ‘Morality Plays’ 239–40.

71 Hall Union 516.

72 See chapter 8 on ‘Amorous Masking’ 180–81.

73 See the useful Appendix to Emigh Masked Performance ‘A List of Basic Questions that might be asked about Performances’ 293–300.

74 André Historia Henrici Septimi 179.

75 Nicolas ‘Garter’ 29.

76 Great Chronicle 315; Kipling Receyt 67.

77 It was the Tuesday before Candlemas, in the period of the Christmas revels.

78 Délyé ‘close-fitting’.

79 Jean Froissart Chroniques in Oeuvres de Froissart edited M. le baron Kervyn de Lettenhove, 25 vols (Brussels: Closson, 1870–87) 15: 85. Enid Welsford suggests that this was a charivari, as the bride was being married for the second time: but there is no evidence for this, and the ‘queer gestures’ and ‘horrible wolfish cries’ exist only in her imagination: The Court Masque (New York: Russell and Russell, 1962) 44.

80 Jean Froissart The Chronicle of Froissart translated out of French by Sir John Bourchier Lord Berners annis 1523–25 introduction by W.P. Ker, 2 vols (Tudor Translations 31 and 32; London: David Nutt, 1903: transcription of edition by Richard Pynson, 1523–25) 2: 96. Berners’ translation anticipates what Froissart does not tell us till later, that the flax was stuck on with pitch. We use his translation, though it is sometimes very free, because it reflects how a courtier of Henry VIII saw the event.

81 Froissart Chroniques 15: 87.

82 Berners Froissart 2: 97.

83 Froissart Chroniques 15: 87–8.

84 Berners Froissart 2: 97–8.

85 ‘The dance of those on fire.’

86 So much emphasis has been laid on carnival as a liberation for the lower classes of society that one forgets that the aristocracy were in their own way equally constrained. For woodwoses in entertainments see R.H. Goldsmith ‘The Wild Man on the English Stage’ Modern Language Review 53 (1958) 481–91; Withington English Pageantry 1: 72–7.

87 Froissart Chroniques 15: 38–42; Berners Froissart 2: 65–73, especially 67.

88 The Roman Pope later maintained it was a warning to the King because he was still supporting the Pope at Avignon: Froissart Chroniques 15: 38–42; Berners Froissart 2: 92–3.

89 E.g. Walsingham Historia anglicana 213: dolo fratris sui Ducis, qui a tempore suœ infirmitatis aspiravit ad regnum (‘by the treachery of his brother the Duke, who in the time of his indisposition had aspired to the kingdom’). The Duchess has here become quœdam domina (‘a certain lady’) who rushes forward and plucks him from the dance. This is an interesting mirror image to the usual ‘assassination attempt during masking’ motif: this time the unmasked figure is accused of the attempt.

90 At the disguisings for the wedding of his brother Arthur and Katherine in 1501 Henry, then Duke of York and a child, dancing with his sister, ‘perceyvyng himself to be accombred with his clothis, sodenly cast of his gowne and dauncyd in his jaket … that hit was to the Kyng and Quene right great and singler pleasure’: Kipling Receyt 58. Such pleasure in personal display continued in adulthood.

91 Hall Union 513–14.

92 Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice and in other libraries of Northern Italy Vol. 4: 1527–1533 edited by Rawdon Brown (London: Longman for HMSO, 1871) 61.

93 Castiglione Il Cortegiano 106.

94 Hoby Courtier 100.

95 Twycross ‘Philemon’s Roof’ 335–46.

96 Kew: Public Record Office E 36/217, fols 23r; 31r; Twycross ‘Philemon’s Roof’.

97 Hall Union 595. See 516, 580, 597, 599 etc.

98 This issue has been widely discussed in Stephen Greenblatt Renaissance Self-fashioning: from More to Shakespeare (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); see also Alistair Fox, The English Renaissance: Identity and Representation in Elizabethan England (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997) 1–6, 59–92.