Around the beginning of the sixteenth century we find another variation in the courtly disguising game. Hall credits Henry VIII with importing it from Italy. In January 1512:

On the daie of the Epiphanie at night, the kyng with a. xi. other were disguised, after the maner of Italie, called a maske, a thyng not seen afore in Englande, thei were appareled in garmentes long and brode, wrought all with gold, with visers and cappes of gold & after the banket doen, these Maskers came in, with sixe gentlemen disguised in silke bearyng staffe torches, and desired the ladies to daunce, some were content, and some that knewe the fashion of it refused, because it was not a thyng commonly seen. And after thei daunced and commoned together, as the fashion of the Maske is, thei tooke their leave and departed, and so did the Quene, and all the ladies.1

This brief paragraph initially caused some stir among theatre historians, since Hall’s use of the word maske suggested that this innovation was the point of origin of the later Stuart court masque which also culminates in dancing with the audience.2 More recent commentators have pointed out that the spectacular element of the masque was simply a continuation of the long established disguising, and the apparent novelty Hall notes seems to be restricted to a particular costume, ‘garmentes long and brode’, and the maskers not dancing just among themselves but taking partners from the audience.3 Hall identifies this as Italian, new, and slightly risqué. Richard Gibson’s Revels’ accounts tell us a little more about the costumes, recording ‘xij nobyll personages, imparylled with blew damaske and yelow damaske long gowns and hoods with hats after the maner of meskelyng in Etaly’.4 This entry confirms that something about the costumes was felt to be new and distinctively Italian. It may have been the shape: the gowns are ‘long and brode’ and also have hoods as well as caps, as specified in the Lisles’ ‘maskyn gownes with hoodes & capps of bokeram’.5 They may have been a version of the typical Venetian carnival domino, the long cloak and wide hood topped by a hat, which effectively disguises the wearer’s silhouette. Both Hall and later commentators assume, however, that the most striking innovation is the involvement of the audience, most often, as here, masked men dancing and ‘commoning’ with unmasked women. Socially this seems to involve a certain element of risk, and in terms of performance it certainly opens a fascinating dimension of interaction between performer and spectator, masked and unmasked.

For want of an exclusive contemporary term for this game, we may call it ‘amorous masking’. Already many kinds of masking carried a certain erotic charge: from the warnings against carnival maskers seducing one’s womenfolk, to Henry VIII’s elaborate courtship disguisings for the young Katherine of Aragon, the excitement and strangeness of the disguised visitation was clearly linked to erotic arousal.6 What we find in the amorous masking is a codifying of this impulse: the erotic encounter is built into the structure of the masking activity rather than being a delightful adjunct.

Henry’s innovation seems to have been a European fashion of the early sixteenth century which both the English and the French claim came from Italy. Word and custom appear at roughly the same time in both countries, though it would appear that the English borrowed the term mask (and probably therefore also the custom itself) from the French masque.7 The fluid and inventive pattern of such entertainments makes it hard to determine any originating moment in Italy. By the fifteenth century Italian carnival masking had taken on such a variety of forms, communal and individual, public and domestic, that variation was more the norm than the exception. At some point, however, in the fifteenth century it apparently became the vogue for groups of well-born young men in masked carnival costume to gate-crash houses where they knew there was feasting and dancing, and invite the ladies of the company to dance with them. Since carnival maskers seem not to have carried the same obligation to silence as mummers, dancing led naturally to flirtation.

This kind of amorous masquerade appears to have been a speciality of Ferrara, perhaps because of the personality and interests of Duke Ercole d’Este (died 1505).8 What may be the earliest reference comes from a Ferrarese chronicle which reports how in 1473:

Se ando in mascara per la citade de Ferara et burgi cum grande triumpho et feste. Et ge andate il prefato duca con tuta la casa de Este; dove par li citadini fu facto festa en le loro case cum damiselli et balli.9

People went in masks through the city of Ferrara and its environs with great pomp and celebration. And the aforesaid Duke also went with all the house of Este, wherever a feast was held by the citizens in their houses with young gentlefolk and dances.

While not precisely specifying that the Duke’s company were either masked or dancing, the conjunction of activities suggests it. If Ferrara was the origin, however, the custom soon spread: Sir Thomas Hoby reports amorous masking in Venice, Marguerite of Navarre sets one in Milan, and the masking in the Romeo and Juliet story is set in Verona where Romeo ‘in maske with hidden face, The supper done, with other five dyd prease into the place’.10

The Italian examples often emphasise the wonderful opportunity this masking gave the young men of eyeing-up and engaging with the young women without either revealing or committing themselves. As Henry VIII himself pointed out, the acknowledged and apparently acceptable aim of such a masking was that ‘havyng vnderstandyng of thys yor tryhumphant bankett where was assembled suche nomber of excellent fayer dames’ the maskers would ‘repayer hether to vewe’.11 Bandello’s 1554 novella as translated by Arthur Broke in 1562 sets the context for Romeo’s first encounter with Juliet:

The wery winter nightes

restore the Christmas games;

And now the season doth invite

to banquet townish dames …

Young damsels thether flocke,

of bachelers a rowte;

Not so much for the banquets sake

as bewties to searche out …12

Although not invariable, this remains a key feature of most amorous masking. A masker encounters an unmasked partner: the flirtation they engage in is shaped partly by the power held by the masker, who can see the other while withholding his (or occasionally her) own identity, and partly by the excitement of the unmasked partner at engaging in amorous exploration with the literally, or supposedly, unknown.

An etiquette apparently developed in Italian amorous masking which implied that after a certain time the maskers should either leave or unmask. Bandello’s (and Broke’s) maskers ‘When they had masked a whyle, with dames in courtly wise, All dyd unmaske … dyd shew them to theyr ladies eyes’.13 There seems to have been a general acceptance of the playful nature of amorous masking, and some respect on both sides for the limits of its licence. But masking etiquette could clearly be fragile: the situation was inevitably fraught, playing openly with all kinds of delicate boundaries of territory and of sexual property. The sensational masking incident recorded by Thomas Hoby in Venice in 1549 reveals how easily this could break down. The ‘lustie yong Duke of Ferrandin’,

… cuming in a brave maskerye with his companions went (as the maner is) to a gentlewoman whom he most fansied emong all the rest (being assembled there a l or lx) … There cam in another companye of gentlmen Venetiens in an other maskerye: and on of them went in like maner to the same gentlwoman that the Duke was entreating to daunse with him, and somwhat shuldredd the Duke, which was a great injurie. Upon that the Duke thrust him from him. The gentlman owt with his dagger and gave him a strooke abowt the short ribbes with the point, but it did him no hurt, bicause he had on a iacke of maile. The Duke ymmediatlie feeling the point of his dagger, drue his rapier, whereupon the gentlman fledd into a chambre there at hand and shutt the door to him. And as the Duke was shovinge to gete the dore open, a varlett of the gentlmanne’s cam behinde him and with a pistolese [short broadsword] gave him his deathe’s wounde.14

The fact that the masking Duke was prepared with a shirt of mail might indicate that the potential dangers of the situation were acknowledged, although such security might belong to his role as Duke rather than that of masker. But the abrogation of rank for the pleasures of anonymity clearly had its dangers: concealment of identity was a crucial factor in the battle for male status and female attention that engendered this violence.

The Italian practice appears to have been a courtly one, involving wealthy households and the youth of the nobility. It was taken up enthusiastically elsewhere, certainly in France where it became so established that by 1528 Gilles d’Aurigny added a sizeable section on it to Martial d’Auvergne’s popular exploration of amorous etiquette, the Arrets d’amours.15 The Arrets present a series of judgements in a mock ‘court of love’ on difficult cases: complaints against the lover who kissed so hard he split his lady’s lip, against the lady who threw a bucket of water over her lover, against bakery shops set up near churches whose smoke impedes lovers trying to watch their ladies going to worship. Gilles d’Aurigny added a fifty second Arret:

Des maris vmbrageux qui pretendent la reformation sur les priuileges des masques tendant à fin de faire corriger les abus, qui s’y commettent, & limiter le temps quilz doibuent demourer, ou assister en chascune maison, ou ilz iront masqués.16

Of the suspicious husbands who claim the reformation of the privileges accorded to maskers, seeking finally to correct the abuses committed by them, and to limit the time that they may stay in each house to which they come in masks.

The Arret reports the husbands’ complaints, the lovers’ defence, and finally twenty-seven court judgements on the management of masking behaviour. Although obviously light-heartedly ironic and therefore to be interpreted with care, this document offers a delightfully detailed account of what might actually happen at an amorous masking, and a playfully revealing view of the expectations and feelings of the various parties involved: husbands/fathers, maskers, and wives/daughters.

The husbands present themselves as due guardians and possessors of their womenfolk who have the right to faire & disposer de leurs dictes femmes, comme vn chascun est vray arbitre & moderateur de sa propre chose (‘do with and dispose of their said wives as each one is a true judge and arbiter of his own property’).17 This proprietorial right is expressed in faintly ridiculous domestic detail hinging more upon the comfort of the middle-aged men than specific control of the women: the husbands claim a right to talk to their wives after supper; to leave a party and go to bed when they feel like it; to lock up their front doors when they please. The amorous maskers, they complain, infringe these rights soubz vmbre & couleur de certains telz quelz priuileges par eulx pretenduz (‘under the colour of some privileges or other laid claim to by them’).18 While the mock legality of the language is part of the joke, it is clear that masking is still associated with ‘privilege’, with licence and liberty not permitted to the unmasked.

The husbands offer a usefully detailed description of the maskers’ behaviour:

… si lesdictz maris sont assemblés en quelque bonne compaignie auecques leurs femmes, & damoyselles, lesdictz deffendeurs viennent & arriuent emmasqués, se saissisent, & emparent desdictes damoyselles, les reculent de la trouppe, les separent & meinent chascun la sienne en vn coing, les confessent à loreille, dancent lun apres lautre la sienne, puis la rameinent. Et des lheure quilz ont chargé vne damoyselle, ilz ne la laissent iamais. Et qui pis est, sont ordinairement depuis huict, ou neuf heures iusques à minuict, ou plus tard, sans partir de là & sans ce quil soit possible leur faire guerpir la place, & sans receuoir lesdictz maris, ou autres non masqués à dancer, ou gaudir auecques eulx ny leur donner leur part du passetemps.19

… if the said husbands are gathered together in some congenial party with their wives and young womenfolk, the said defendants will come and arrive in masks, seize and monopolise the said young women, withdraw them from the flock, separate and lead them, each one his own, into a corner, whisper in their ears, dance one dance after another, each one with his chosen partner, then bring her back [to sit down] again. And from the time when they have laid claim to a young lady they never leave her. And what is worse, they are often there from eight or nine in the evening until midnight or later, without leaving, and without permitting the said husbands or anyone else who isn’t masked to dance or have fun with them.

Husbands meanwhile sit humiliated, unable to go to bed or to recall their wives without being labelled ‘jealous’. The anonymity of the masks may be reinforced by wearers who supposent souuent le nom dautruy, se disent princes, & contrefont la court (‘often adopt others’ names, call themselves princes and pretend to be courtiers’).20 According to the husbands this seduces the young women lesquelles souuent se decellent, & descouurent leur courage ausdictz masqués, pensans quilz soyent ceulx quelles supposent (‘who often betray themselves and reveal their feelings to the said maskers, thinking that they are the people they pretend to be’).21 Masks are presented as interfering with proper social, personal, and class relations: they can be used to assume, as well as to put off the powers of high rank, and to invite inappropriate self-revelation from the unmasked, who remain the vulnerable partners in the relationship. Amorous masking is also accused of causing more obvious social upset: the maskers bring unruly servants who cause chaos in the kitchen; and they carry many open and concealed weapons which threaten the proper territorial power of the householders:

… en maniere que la force est deuers eulx, & leur demeure, & que lesdictz marys en leurs maisons ne seroyent les plus fors.22

… in such a way that power lies with them and their visitation, and that the said husbands in their houses are no longer the more powerful.

The maskers offer a defence formally couched in terms of the pleasurable and proper licence permitted to masking. Love allows the maskers grandz priuileges, franchises, libertés, & immunités (‘great privileges, freedoms, liberties, and immunities’)23 which permit them to faire Lamour, destre braues, emplumés, desguysés, descouppés, masqués, musqués, parfumés, & en bon ordre (‘flirt, be handsomely dressed, befeathered, ultrafashionable, slashed and jagged, masked, musked, perfumed, and dressed to kill’).24 They are free to attend all parties where there are young women present, bring music, and choose flirting partners. The husbands have no right to resist and the masker may continue either until the lady responds favourably, or iusques à ce … que ledict masqué congnoisse quil luy soit fascheux, & importun (‘until the said masker realises that he is annoying or pestering her’).25 The maskers define the power-structure of amorous masking as excluding the husbands altogether; between the masked man and the unmasked woman the licence is mostly on the side of the anonymous masker, but the final power is throughout defined as resting with the woman. Amorous masking is said to offer a positive benefit to the young women as well as the young men since both can develop their social skills and learn the civilised manners appropriate to lovers. Arguing for more time, rather than less, the maskers turn the husbands’ fear of anonymity and assumed identities back against them, pointing out that:

… le masqué de sa nature est subiect à desguisement, ou supposition, & est inuentee à ceste fin, & deuroyent lesdictz marys plus craindre la supposition de leurs femmes que du nom dautruy.26

… masking by its nature is subject to disguise and guesswork, that’s what it was invented for, and the said husbands should be more afraid of the suggestibility of their wives than of some false name.

As elsewhere, the mask clearly carries opposing significations: its concealment of identity, the licence it offers to both masker and unmasked, the imaginative power to assume a new persona, are dangerously disruptive to one group, delightfully liberating and extending to the other.27

A series of judgements are made by the court which, although certainly favouring the maskers, establish certain curbs and appropriate boundaries for the game. The first judgements set ground rules. We find a class restriction for amorous masking: everyone may mask at the appropriate time except marchans, & gens de basse condition (‘merchants and lower-class people’)28 who must restrict themselves to mumming.29 New maskers must accompany those more experienced and must initially practice only on the ladies’ maids. Maskers must be welcomed, taking priority over tous les assistans non masqués (‘all those present who are not masked’)30 who must leave the ladies when maskers approach. The ladies are obliged to co-operate, and husbands must keep their distance on pain of being declared ialoux, plein de mauuaise grace, & apte à estre coqu (‘jealous, ungracious, and ripe to be cuckolded’).31

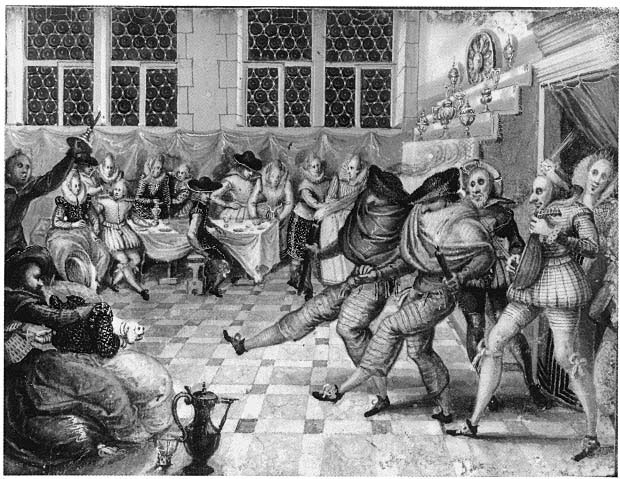

PLATE 20: Disguisers gatecrash a mixed party. Album amicorum of Moyses Walens of Cologne, entry by Edouard Bocher (1610). British Library, Additional MS 18991 fol. 11r.

© Reproduced by permission of the British Library.

Further judgements then regulate the maskers: they may not wear last year’s costumes, they may mask only in the season (from Martinmas to Holy Week), and only after dark. They are free to enter houses, but may mask there for only one hour after which they must either leave or se demasquer, lesquelz demasqués seront tenus & reputés compaignons de lassemblee (‘unmask themselves, when they will be held and judged to be simply members of the party’).32 They must also be thanked for their visit by the householder. These judgements clearly concern the proper territorial rights and balance of power between masked visitors and unmasked householders. While the liberties of masking are confirmed there is also a recognition of the limits of licence: it is of fixed duration, its freedoms defined by mask-wearing. In spite of their pleasurable otherness, it is also assumed that the maskers beneath their disguises should be the equals of those they visit: the same class, with the same expectations, who can be treated as compaignons de l’assemblee.

Maskers were clearly not just gatecrashers, but were assumed to be providing the party with a certain entertainment and are obliged to bring music if need be. But a series of judgements are also concerned with the delicate amorous interaction between maskers and unmasked. The maskers are forbidden to assume false names, although they may contrefaire le langaige, & mentir tant que bon leur semblera (‘disguise what they say and lie as much as they think fit’).33 So they may not assert false identities that might lead to complications outside the confines of the game, but are free to play with concealment and fictitious roles in order to establish an imaginary space for love encounters. The same concern to keep masking encounters separate from existing relationships seems to prompt the rule that husbands must not go masking in order to test their wives.34 Within the charmed circle of the masking encounter maskers are free to taster, baiser, accoler, & passer oultre silz ont laisement, sauf aux damoyselles leur deffenses au contraire (‘touch, kiss, embrace, and go further if they want, provided the young women do not forbid them’). Everyday reality is also kept at bay by the injunction that neither party is to use de parolles rigoureuses, & touchans aucunement lhonneur (‘harsh words in any way touching matters of honour’).35 All is to be taken lightly and in good part. This extends beyond the amorous encounter itself, since maskers are forbidden to set out with intent to pick a fight, and should gloss over any ill will or quarrel they encounter. The masking space must be both privileged and protected.

The final group of judgements concerns the relationship of amorous masking to wider society outside the courtly or noble circle. Silk and wool merchants, hatmakers, plumers, embroiderers, valentine-, mask-, and perfume-sellers are all enjoined to lend or let out their wares on credit during the masking season, after which the maskers must settle up. If such generous terms testify to wishful thinking on the part of the maskers, they nonetheless indicate the lavish display and expenditure associated with amorous masking. The role of bystanders is also considered, as the musicians who often come to recognise the maskers par leurs accoustremens, marché, contenance, maniere de dancer & autres signes & indices (‘by their costumes, gait, appearance, manner of dancing, and other signs and tokens’)36 are forbidden to spoil the game by disclosing their identity. Attendants are not to intervene in the closed circle of the game.

The whole of this document is, of course, deliberately ironic. It belongs to the mingled worlds of the cause grasse, the mock lawsuit debated before the Abbot of Unreason or Prince des Enfants-sans-souci during Shrovetide, and of the demande d’amour which debates problems of love and love-etiquette in a mock-serious manner. Neither is concerned with accurate realism: the causes grasses are as outrageous as the upside-down, libertarian world of Carnival demands, and the demandes d’amour, like these Arrets, are presented to the jurisdiction of la chose publique d’amours (‘the republic of love’). The authority of both Carnival and love naturally biases the Arrets towards the masked lovers; but it may well also be that many of the original readers were maskers themselves. The playful but technical legal terminology might suggest an audience of law students, and students were certainly associated with such masking games.37 Although it is pointed out that these encounters can lead to advantageous marriages,38 in general the maskers are associated with messieurs les mignons,39 the jeunesse dorée of the court and city, delightful, irresponsible, and disingenuous, who are out to cocufy the husbands. The husbands are dismal, stuffy, bourgeois, bored and boring, who by midnight would rather be home in bed.

The generic background this masking scenario draws on is the fabliau triangle of jealous husband, beautiful wife, and young lover. The maskers play the lover; the husbands are attacked with the stock epithets for the cuckold: jaloux, umbrageux, accused of cecité (‘blindness’), avarice, and chicheté (‘niggardliness’). Not only unmarried daughters but wives too are most often described as damoyselles and edged into the role of the mal mariée: marital sex is presented as a duty rather than a pleasure, the wives reluctant or unsatisfied and only too willing to be courted by a mysterious stranger. Another part of the fabliau ethic informs the parody of the lawsuit. The husbands’ relationship with the wives is clearly expressed in terms of property, the husband is vray arbitre & moderateur de sa propre chose (‘true judge and disposer of his own property’); the rights of marriage, droict commun damour maritale, are set against the privileges and freedoms of the mask.40

As in Carnival, the maskers’ alternative world sets irresponsibility against responsibility, the playful against the earnest. Like mumming it creates a game-world with its own rules which exists only in the present: part of the mask’s power is to negate consequence. The Arrets even suggest that it is safer for a wife to be seduced by a masker than by a neighbour’s husband, which would keep the affair in the community, becoming tous vulgaires, & sen rapportoyent à la commune renommee desdictes femmes (‘common property, and appertaining to the public good name of the said women’).41 A masker, on the other hand, comes and goes without past or future. Juliet’s urgent need to discover Romeo’s identity from her nurse in Bandello, Broke, and Shakespeare emphasises the dazzling briefness of the ideal masking encounter. This fantasy of the unknown, exotic stranger (possibly a prince), who will override the conventions and rights of husband’s or father’s authority, inviting the woman into an intense intimacy without consequence or responsibility is, even more than the public encounter of Carnival, potently erotic.

Like the more traditional popular game of mumming, amorous masking was soon, as we have seen, adopted and transformed by the English court. The exuberant accounts of Hall suggest that Henry VIII in his early years as king was already making amorous use of the courtly disguising. The delighted glamour with which he devised and took part in masking encounters for his young bride, Katherine of Aragon, concealing but displaying himself, surprising and engaging his wife, suggest that the amorous masking was a perfect form for him. Contemporaries registered the amorous charge Henry found in the mask: in 1537–8 Eustace Chapuys, the Emperor’s ambassador, wrote to Mary of Hungary, ‘He cannot be one single moment without masks, which is a sign that he purposes to marry again’.42 It seems natural that Shakespeare should show Henry falling in love with Anne Boleyn at such an amorous mask, transforming the courtly mumming at Wolsey’s palace described in the previous section to this appropriately erotic form.

The ‘maske’ of 1512 described by Hall, while retaining the formal qualities of the courtly disguising, nonetheless clearly includes almost all the elements of amorous masking. A company of young men, spectacularly dressed, masked, and accompanied by torchbearers, enter a party after supper and invite the ladies of the company to dance. After the dance they ‘commoned together, as the fashion of the Maske is’ before, in this case, leaving still masked. What presumably rather alters the dynamic of the occasion is that the maskers, even if temporarily unrecognised, were most certainly known; and there is no clash of authority with a jealous husband or father: masker, husband, and monarch are one.

Hall implies that this new custom was received with some caution by the ladies. They appear to recognise and initially resist the risky public intimacy the amorous mask involves: ‘some that knewe the fashion of it refused, because it was not a thyng commonly seen’.43 But any such scruples must soon have dissolved since this pattern of masking very soon appears entirely ordinary. It became almost customary for disguisings to conclude with the maskers dancing with guests at the assembly rather than with each other, ‘these revelers toke ladies & daunced’; ‘then the Maskers toke Ladies, & daunsed a greate season’; ‘these Maskers tooke Ladies and daunsed lustely about the place’.44 The singular intimacy and amorous intensity of the private-public encounter of the amorous mask no longer seems central. This may be just another example of the fluid interweaving of different forms of courtly masking – the disguising simply borrows formal elements from the amorous mask, as from the popular mumming, and adapts them for its own purposes. Alternatively Henry’s increasing age may have reduced the focus on his role as central, and by implication youthful, amorous masker. But what remains is nonetheless significant for the model of courtly entertainment: a show which is put on for the members of the court by the members of the court first intensifies the separation between performer and audience but then dissolves it. The exotic strangeness of the maskers remains important, but it is now brought into direct engagement with the unmasked members of the court.

If such modified amorous masking became almost routine at court, it could also break new ground. The potential intimacies of the amorous masking form were sometimes drawn directly into the political activity of the court. One example arises in 1519 over the affair known as the ‘expulsion of the minions’.45 A group of young men of the Privy Chamber ‘whiche were called the kynges minions’ had recently returned from protracted negotiations in France; according to Hall they had enthusiastically joined in the carnival masquerading of Francis I and when they returned ‘nothing by them was praised, but it were after the Frenche turne’.46 The King’s Council, anxious about the over-familiarity and ‘light touches’ of the young minions, requested their banishment from the court, replacing them with ‘foure sad and auncient knightes, put into the kynges privie chamber’. Some six months later at a ‘sumpteous banket’ at Beaulieu:

… entered into the chamber eight Maskers with white berdes, and long and large garmentes of Blewe satten pauned with Sipres, poudered with spangles of Bullion Golde, and they daunsed with Ladies sadly, and communed not with the ladies after the fassion of Maskers, but behaved theimselfes sadly. Wherefore the quene plucked of their visours … [revealing the four ‘sad and auncient knightes’ of the privy chamber] … all these wer somwhat aged, the youngest man was fiftie at the least. The Ladies had good sporte to se these auncient persones Maskers.47

The political upheaval of the inner court is being playfully enacted in this mock-amorous mask. The age and venerability of the new inner circle is jokingly played off against the young, flirtatious implications of the amorous mask, and indeed the banished masking minions themselves The ‘auncient persones’ participate in and condone the King’s youthful pleasures, but in a manner ‘not after the fassion of Maskers’ which humorously emphasises their distance from the game, its glamorous display, and its public-private intimacy. These elderly maskers were then succeeded by an amorous mask of the King with ‘other young gentlemen’ who ‘daunsed & commoned a great while’ in expected manner, thus replacing the parodic ‘antimask’ with the real thing. Although clearly a light-hearted joke, the episode shows a lively awareness of the forms and implications of amorous masking as well as a sophisticated sense of how such entertainment might partake in and comment on topical politics in the enclosed but semi-public arena of the court.

Another moment where we find amorous masking participating in political events falls in 1532, in the final stages of Henry’s long fight for the annulment of his marriage with Katherine of Aragon. Having already effectively separated from Katherine and on the brink of marriage with Anne Boleyn, he engaged in a ceremonial visit to Francis I, overtly to confer about the Turkish threat to Christendom but apparently more immediately to invite Francis’ support for his second marriage.48 Anne, by now Marchioness of Pembroke, was with the party when Francis was entertained at a costly supper in Calais:

After supper came in the Marchiones of Penbroke, with. vii. ladies in Maskyng apparel … the lady Marques tooke the Frenche Kyng … and euery Lady toke a lorde, and in daunsyng the kyng of Englande, toke awaie the ladies visers, so that there the ladies beauties were shewed, and after they had daunsed a while they ceased, and the French Kyng talked with the Marchiones of Penbroke a space.49

Here we have a manipulated version of an amorous masking with the usual gender roles reversed. Henry has plainly designed the occasion to set up a public-private encounter between Anne and Francis: the demands of the game require the French king to co-operate in a public intimacy initiated by the masked Anne. He is cast (presumably willingly) in a performance of quasi-amorous approval of the prospective bride. Henry himself, however, has appropriated the moment of unmasking: Anne’s identity is revealed by him rather than by her, before rather than after the flirtatious conversation. She becomes the token of exchange between the two men, rather than the initiating masker. Henry had made similarly political interventions in masking play before. At an entertainment celebrating a contract of marriage for the young Princess Mary in 1527, he drew his daughter from among the disguisers and dramatically plucked off her elaborate masking head-dress ‘and the net being displaced, a profusion of silver tresses as beautiful as ever seen on human head fell over her shoulders, forming a most agreeable sight’.50 Henry uses the playful unmasking to assert his own authority over the women’s identities, generously revealed by him as a gift to the spectators. In both cases the disguising, and the unmasking, feed into the political situation.

If Henry VIII enthusiastically adopted amorous masking, it is worth considering how far the practice became popular outside of the court. There are many English references to wealthy citizens arranging for ‘masks’ at their children’s weddings and other celebrations, although these sound more like versions of the disguising, perhaps with modifications, than the kind of informal amorous masking from which we began. One account of a domestic wedding, for example, describes disguisers who enter in masks, dance with the women, but also bring out money for mumchance.51 The term mask so quickly gained such wide currency that it is not itself a reliable indication of the nature of the disguising involved. A story, from the reign of Mary I, however, in which an old enemy of a Devonshire noble employed a version of an amorous mask to make a public and humorous reconciliation, seems to imply that such masking was not considered wholly unusual. A band of maskers disguised as armed men approached the house of Sir Richard Edgecombe, causing anxious defensive preparation; but ‘their Armor and weapons were only painted Paper, as by nearer approaching was perceived; and instead of trying their force with Blows, in fighting with Men, they fell to make proof of the Ladies Skill in Dancing’.52 The dancing concluded, the leader unmasked and proposed reconciliation with Sir Richard. Although this amorous masking was exploited for political purposes, it retained its traditional associations: Sir Richard was invited to match one of his daughters with the heir of his opponent ‘a young Gentleman … (who being of fair Possessions, came amongst the other Company, masked in a Nymph’s attire)’.53 Masking and marriage continue to keep company.

Amorous Masking in Literature and Drama

Amorous masking was a game which might clearly be used for different ends in different situations. Contemporary understanding of its possibilities can be elucidated from its presentation in literature: perhaps predictably, given its focus on individual and romantic encounter and on the teasing relationship between mask and face, amorous masking is more widely represented in sixteenth-century literature than any other contemporary masking activity. Masks are understood as having both positive and negative effects on amorous encounters. One commonly asserted paradox is that the mask can reveal truth: the mask provides a release from shy inhibition that gives the speaker boldness to express his (or occasionally her) real feelings. Philautus in Euphues and his England tells his lady that, ‘It hath been a custome … how common you know, that Masquers do therfore cover their faces, that they may open their affections’.54 Literary and dramatic exploitation of this opposition between the falseness of the mask and the sincerity of the speaker is widespread. Curiatius in George Pettie’s Petite Pallace of Pettie his Pleasure shows the delight taken in expanding the images of opposition, presenting himself as ‘in steed of a masker a mourner … I thought beste under this disguised sorte to discipher plainly unto you the constancy of my good will’. His lady’s reply multiplies both the counterpoint, and the play with masking forms: ‘you shall have cause to count this your labour lost … for my part I promise you I had rather have bene matcht with a mery masker then a leude lover … This rigorous replie of his Misteris converted him from a masker to a Mummer, for hee was strooke so dead herewith that the use of his tounge utterly fayled him’.55

The licence endowed by the mask is seen then as capable of revealing truth, although indirectly and enigmatically. Yet it can also be abused. Released from responsibility, the masker can violate boundaries and taboos. Vives suggests that maskers dicunt intrepide quae ne cogitae auderunt si nosceretur (‘boldly say things they would not dare to think if they were known’);56 for as Bouchet points out le masque ne rougit point (‘the mask does not blush’).57 The amorous mask can easily become the brazen face of insolence, as Euphues’ Philautus is told by his lady, ‘Though you can utter by your Visard whatsoever it bee without blushing, yet cannot I heare it without shame’.58 Thais, when so approached in Marston’s The Insatiate Countess, ripostes by addressing herself directly to the hidden face, thrusting aside the liberating protection of the mask, ‘methinks, sir, that you should blush e’en through your visor’.59

Yet as these examples show, if the (usually male) masker finds freedom in his visor, the unmasked woman he addresses can also be represented as liberated by the amorous mask. The power balance between masked and unmasked seems different from the encounters of mumming, where privilege belongs to the masker. The potential power of the unmasked woman over the masked man lies partly in the freedom she shares with him to speak more boldly than usual, which allows her to tease or insult the visored suitor. But if the fictional versions are to be trusted, the woman’s power could also be exercised by covertly ignoring the mask’s persona and addressing the man beneath. This was Thais’ strategy in defending herself against the harassment of an unblushing mask. It is also what we find in the witty women of Shakespearean comedy who attack their visored suitors, transforming the mask from a liberation to a trap.

Shakespeare’s plays show a wide knowledge of masking customs, and a lively sense of their theatrical potential. Apart from the scenario in King Henry VIII, which he (or Fletcher) found in Holinshed,60 and the interesting blend of folk mumming and sophisticated masque in The Merry Wives of Windsor, his masking scenes tend to be set in Mediterranean countries. The Venetian Carnival provides the cover for the stealing of Jessica in The Merchant of Venice, Verona is the setting for the amorous masking visit in Romeo and Juliet. But Shakespeare seems to assume that the audience will recognise the various forms, and will pick up the often quite complex nuances in their presentation. Even the most straightforward plot-oriented incidents have resonances which vibrate with the themes of the rest of the play. They largely appear in romantic comedy, as masking is particularly suited to courtship, its subterfuges and its illusions.

Jessica is stolen away in a carnival masquerade. Although dressed as a boy she does not seem to be masked herself, but the masquerade of ‘Christian fools with varnished faces’61 provides a visual footnote to the central play of illusion and reality in the casket scenes and even the benevolent deception by Portia and Nerissa. In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Master Fenton similarly steals Anne Page in the scintillating confusion of the fairy masquerade, where all the players are ‘mask’d and vizarded’.62 In each of these the theft of a bride by a masked lover is approved by both the social and comic ethos,63 and no shadow is cast on the masking itself.

In a different kind of play it can take on a darker and more ambiguous colouring. In Henry VIII it is difficult to tell if the audience is meant to feel uneasy about Henry’s masking encounter with Anne Boleyn:64 probably for political reasons, the play’s moral stance is curiously uncommitted. In Romeo and Juliet, the masking is the pivot which swings comedy into tragedy. Romeo’s mask enables him lightheartedly to infiltrate Capulet’s house, and once there, the rules of engagement, as Old Capulet nostalgically agrees, dictate that he should be treated as a guest. Romeo and Juliet themselves are wilful victims of the game. When they meet, neither knows who the other is:65 it is the ideal masking encounter. Its erotic intensity should have been matched by its brevity; but, swept away by the force of emotion, and the illusion of self-determination, they break the rules and attempt to make the fantasy world permanent. The very real danger and impossibility of the situation prolong the intensity66 and enforce the secrecy, and the protagonists push themselves over the edge into tragedy. The romance ethos demands that we see their love as they do, an overriding passion worth dying for, and the older generation is made to carry the blame. Had the two houses not been at enmity, perhaps the encounter would have led, as in the Aresta amorum, to a bon mariage, and the tragedy would have been a comedy. But the masking leaves us with ambivalent questions about the nature of romantic love, rebellion, and self-destruction, and public and private selves.

The two plays in which the implications of masking are most fully dramatised are Much Ado about Nothing and Love’s Labour’s Lost. Both introduce masquerades as, apparently, largely gratuitous entertainments: neither is essential to the plot in the same way as they are in the previous plays. But both these apparently ornamental spectacles are essential to the thematic purposes of the plays, and both hint at the darker possibilities inherent in the form.

The complexity of perceived tension between face and mask, hidden truth and outer artifice, reaches a climax in Much Ado about Nothing. This play stages a traditional amorous mask in Act 2, Scene 1, in which the masked men of the court choose unmasked dancing partners from among the women; they then play out a range of encounters all hinging on the interplay between sincerity and falsehood. The Prince, wooing Hero by proxy for the apprentice masker Claudio,67 alerts her obliquely to his concealed status: ‘My visor is Philemon’s roof; within the house is Jove’.68 His claim to be a prince, though in this case true, echoes the deceptive extravagance of the maskers of the Arrets d’amours. Beatrice’s needling encounter with Benedick leaves him, on the other hand, helplessly trapped in his mask, fretting ‘that my Lady Beatrice should know me and not know me … she told me, not thinking I had been myself, that I was the Prince’s jester’.69 Ursula, correctly identifying the aged Antonio beneath his mask ‘by the waggling of your head’ is met with the double-bluff, ‘To tell you true, I counterfeit him’.70 All three depend on multiple levels of truth and falsehood, identity and disguise, signalled by one side and interpreted by the other yet never openly acknowledged. This amorous mask, like the presentation of the masked Hero to Claudio at the end of the play, is a literal enactment of a game with masks which invades the language and ideas of the whole play. Shakespeare even seems to draw on the masking customs of Spanish Carnival, apparently alluding to the masked orange-fights as Count Claudio71 angrily rejects Hero with ‘Give not this rotten orange to your friend’.72 The ambience of these various masking games with their play of identity lends some credence to Claudio’s problematic psychology of misinterpretation and mistrust. Claudio’s readiness to believe that appearance is reality and reality appearance, his inability to distinguish the blush of modest innocence from the blush of guilt, his need to learn to recognise inner rather than outer truth, all relate closely to the complex play between mask and face implicit in amorous masking.

The multiple power possibilities latent in the form are vividly apparent in the paradoxical masked encounter of Love’s Labour’s Lost, where Shakespeare upends the expectations of the amorous mask at the men’s expense. The disguising which Berowne and his companions stage to the Princess of France and her ladies is clearly designed as an amorous mask. As Boyet reports, ‘their purpose is to parle, to court and dance’.73 Apparently their entertainment is somewhat dated: extravagantly costumed as ‘Muscovites’, at the beginning they pretend silence and are accompanied by a Presenter (Moth) although, as Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet tells us, ‘the date is out of such prolixity’.74 The women assert their mastery of the occasion and power over the masked men by a novel reversal of etiquette: they decide to assume masks themselves75 leaving the men bemusedly unable to identify the partners of their choice.

In the sparring match that follows we find the men, trapped in their fantastic personae as Muscovites, the butt of the women’s agile ridicule. The women play fleetly between two positions of strength: they retain their traditional power to refuse the terms of the masked game and address themselves directly to the men beneath the visors: ‘Adieu; Twice to your visor and half once to you’.76 Yet equally they appropriate to themselves the power of concealment, knowing that the men truly do not know their identities:

Berowne: |

Vouchsafe to show the sunshine of your face … |

Rosaline: |

My face is but a moon, and clouded too.77 |

Female superiority consists in the power to manipulate the multiple interactions of mask and face, leaving their suitors trapped in their own game:

Princess: |

Will they not, think you, hang themselves tonight? Or ever but in visards show their faces?78 |

Coming as he does at the end of this tradition, Shakespeare can reveal in its full complexity the shifting play of amorous power, the subtle interplay of mask and face that amorous masking involved. The visual splendour and glorious display of the disguising has developed into this subtle and shifting dynamic between man and woman, revealed and concealed identity. This shift in focus from display to concealment may lie in the very fact that amorous masking makes such play of the mask-face relationship. Unlike mumming, in which the mask seems largely to obliterate the identity of the wearer, the amorous mask holds the two very much in tension, deliberately flirting with identity that is teasingly hidden but not quite denied. Since, at least for the duration of the encounter, the masker must not reveal his identity, the unmasked woman who can play at will between the world of the mask and the world of the real face beneath may ultimately come to have an advantage over the man who is limited to the mask.

Notes

1 Hall Union 526.

2 Reyher Les Masques anglais 12–13; Welsford Court Masque 130–42. For a summary of more recent opinion see Streitberger Court Revels 82–3.

3 Wickham Early English Stages 218–19; Anglo ‘Early Tudor Disguising’ 3–9.

4 Kew: Public Record Office E 36/229, fol. 175.

5 Lisle Letters 6: 201.

6 See chapter 3 on ‘Carnival’ 71–2.

7 Neither is, phonetically, a direct borrowing from the Italian maschera or mascherata, although the earliest use of the term cited in the OED comes in a letter on behalf of Henry VIII reporting that he intends to meet the French king ‘in Calais in masker’, which seems to be. Reyher suggests that the custom was imported into France during the reign of Louis XII (1498–1515) who brought it back from his military and dynastic adventures in Italy (Les Masques anglais 26–7).

8 See chapter 3 on ‘Carnival’ note 8.

9 Diario ferrarese dell’ anno 1409 sino al 1502 edited Giuseppe Pardi (Rerum Italicarum Scriptores 24:7; Bologna: Zanichelli, 1933) 85.

10 The Travels and Life of Sir Thomas Hoby … 1547–1564 edited Edgar Powell in Camden Miscellany 10 (Camden Society Series 3: 4; London: Royal Historical Society, 1902) 14; Marguerite de Navarre The Heptameron translated P.A. Chilton (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984) Day 2, Story 14, 181; Arthur Broke The tragicall Historye of Romeus and Iuliet (London: R. Tottell, 1562) fol. 5v. Note that Romeo is one of a dancing team of six.

11 Cavendish Wolsey 26–7.

12 Broke Romeus and Iuliet fols 5r–5v.

13 Matteo Bandello Tutte le opere di Matteo Bandello edited Francesco Flora, 2 vols (Milan: Mondadori, 4th edition 1966) 1: 730; Broke Romeus and Iuliet fols 5r–5v.

14 Travels and Life of Sir Thomas Hoby 14.

15 Martial d’Auvergne Aresta amorum 405–30.

16 Aresta amorum 405.

17 Aresta amorum 405.

18 Aresta amorum 406.

19 Aresta amorum 406.

20 Aresta amorum 407.

21 Aresta amorum 407.

22 Aresta amorum 408.

23 Aresta amorum 409.

24 Aresta amorum 410.

25 Aresta amorum 410.

26 Aresta amorum 415–16.

27 See chapter 3 on ‘Carnival’ 53–4, 66–8.

28 Aresta amorum 422.

29 See chapter 4 on ‘Mumming’ 86.

30 Aresta amorum 423.

31 Aresta amorum 424.

32 Aresta amorum 425.

33 Aresta amorum 427.

34 A comic story by Bouchet tells of a group of husbands who did so, one of them energetically seducing his own wife behind an arras. Spying him lifting his mask afterwards to wipe his sweaty face, she exclaims, Est ce vous, mon mary? pardonez moy, ie pensois bien que ce fust vn autre (‘Is that you, husband? I’m so sorry, I thought it was someone else’): Serées 1: 137.

35 Aresta amorum 427.

36 Aresta amorum 429.

37 The Twelfth Night company in Bouchet’s tale thinks that the unknown mummers must be students: Bouchet Serées 1: 131–6. A possible audience for the Arrets might be the Paris Basoche, the confrérie associated with the Sorbonne.

38 Aresta amorum 413: se brassoyent & marchandoyent plusieurs bons mariages par les approches que y font les ieunes ommes à marier en masqué.

39 Aresta amorum 407.

40 Aresta amorum 405.

41 Aresta amorum 412.

42 Calendar of Letters, Despatches, and State Papers relating to the Negotiations between England and Spain, preserved in the Archives at Vienna, Brussels, Simancas and elsewhere, 1485–1558 edited Gustav Adolph Bergenroth, Pascual de Gayangos, and others, 13 vols (London: HMSO, 1862–1954) 5:2 (1888) 520, item no. 220.

43 Hall Union 526.

44 Hall Union 613, 690, 724.

45 Greg Walker Persuasive Fictions: Faction, Faith and Political Culture in the Reign of Henry VIII (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996) 35–53: chapter 1, ‘Faction in the Privy Chamber?: the “Expulsion of the Minions”, 1519’.

46 Hall Union 597. The French also objected to this behaviour. The journal of a Paris citizen records that in 1517 Francis I and his companions spent the carnival season en habitz dissimulez et bigarrez, ayans masques devant leurs visaiges, allans à cheval parmy la ville et alloient en aucunes maisons jouer et gaudir; ce que le populaire prenoit mal à gré (‘in deceptive and motley costumes, with masks in front of their faces, riding through the city and they would go into various houses to play and make merry; at which the populace were not pleased’): Journal d’un Bourgeois de Paris sous le règne de François Premier edited Ludovic Lalanne (Paris: Renouard, 1854) 55.

47 Hall Union 599.

48 Lisle Letters 1: 249.

49 Hall Union 793–4. See also Wynkyn de Worde The Maner of the tryumphe at Caleys and Bulleyn (London: Wynkyn de Worde, 1532).

50 Calendar of State Papers: Venetian 4: 61; see Carpenter ‘Sixteenth-century Court Audience’ 11.

51 Bernard Garter The Tragicall and True Historie which happened betwene two English louers, 1563 (London: R. Tottell, 1565) fol. 36v.

52 John Prince Damnonii Orientales IUustres: The Worthies of Devon (Exeter: S. Farley, 1701) 285.

53 Romeo in the Italian version by Da Porta also arrives at Capulet’s dressed as a nymph: Luigi Da Porta Istoria di due nobili amanti (1539) in Novellieri del cinquecento edited Marziano Guglielminetti, 2 vols (La Letteratura Italiana Storia e Testi 24: Milan: Riccardo Ricciardi, 1972) 1:248, 249.

54 John Lyly Euphues and his England (London: William Leake, 1605) N3v.

55 George Pettie A Petite Pallace of Pettie his Pleasure (London: R.W., 1578?) 141–2.

56 See chapter 11 on ‘Ideas and Theories’ 307.

57 Bouchet Serées 1: 139 (Quatriesme serée). Mercutio turns the idea on its head, with ‘Here are the beetle brows shall blush for me’, suggesting that he himself is shameless: Romeo and Juliet Act 1 Scene 4, line 32.

58 Lyly Euphues N4r.

59 John Marston The Insatiate Countess in Works edited Arthur Henry Bullen, 3 vols (Hildesheim: Olms, 1970: reprint of 1887 edition by John C. Nimmo) 3: 159; Act 2 Scene 1, line 142.

60 See Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare edited Geoffrey Bullough, 8 vols (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1957–75) 4: 478–81. This was the scene that burned down the Globe Theatre in 1613: William Shakespeare and John Fletcher King Henry VIII, or All is True edited Jay L. Halio (Oxford Shakespeare; Oxford University Press, 1999) 16–17. The stately vision of Queen Katherine in Henry VIII (Act 4 Scene 2), like the wedding masque of Ferdinand and Miranda in The Tempest (Act 4 Scene 1), belongs to a later tradition than those with which we are concerned.

61 Merchant of Venice Act 2 Scene 5, line 33.

62 Merry Wives of Windsor Act 4 Scene 6, line 40.

63 Masking allows them to ‘play the thieves for wives’: Merchant of Venice Act 2 Scene 6, line 23. Lorenzo is making an overt comparison with masked burglars and highwaymen: compare Henry IV Part I Act 1 Scene 2; Act 2 Scene 2.

64 Holinshed’s courtly mumming at the Cardinal’s is converted into a more straightforwardly amorous affair, removing the dicing and the ambiguity surrounding the unmasking of the King, so as to create the sexually-charged atmosphere in which Henry first encounters Anne. Their first physical contact is presented as part of the etiquette of the occasion: ‘Sweetheart, It were unmannerly to take you out (i.e. to dance) And not to kiss you’.

65 It is not clear from the script exactly where Romeo unmasks, but in the sources, he has done it before the torchio dance which brings him face to face with Juliet. This creates the beguiling illusion of total frankness when he declares his love for her.

66 In the balcony scene, Juliet, her everyday self concealed by ‘the mask of night’ (Act 2 Scene 2, line 85), ‘opens her affections’ with unaccustomed boldness.

67 See the Aresta amorum 422. Don Pedro, as an ancien compaignon masquier, takes it upon himself to woo Hero in Claudio’s place: Claudio is either a lot younger, or a lot less experienced, than modern productions tend to make him.

68 Much Ado Act 2 Scene 1, line 95.

69 Much Ado Act 2 Scene 1, lines 201, 240.

70 Much Ado Act 2 Scene 1, line 115.

71 Described as ‘civil [Seville] as an orange’ Much Ado Act 2, Scene 1, line 291.

72 Much Ado Act 4, Scene 1, line 31.

73 Love’s Labour’s Lost Act 5, Scene 2, line 122.

74 Romeo and Juliet Act 1, Scene 4, line 3.

75 Probably not the fantasy masks of the disguising, but their everyday cosmetic ‘sun-expelling’ masks [see Plate 30]. See chapter 11 on ‘Ideas and Theories’ 307–8.

76 Love’s Labour’s Lost Act 5, Scene 2, line 226.

77 Love’s Labour’s Lost Act 5, Scene 2, lines 201,203.

78 Love’s Labour’s Lost Act 5, Scene 2, lines 270–71.