Mystery plays remain for most readers and audiences today the most familiar form of medieval English drama. While there are many literary, textual, and cultural reasons for this, one major influence on their modern accessibility has come from performance. From the first re-staging of the York plays at the Festival of Britain in 1951, increasing numbers of community, university, and professional groups have brought performance of the mysteries to a wider audience than at any time since the Reformation. Besides this, on-going research into dramatic records has given a sharper insight into the material fabric of performance, which has fed into experimental reconstructions of medieval staging. Some of these have been extremely persuasive, though we hardly need to say that they prove nothing about actual medieval practice. On the other hand, they alert us to questions and possibilities, and it seems legitimate to refer to them in our discussion, with all the proper caveats.

This recent focus on performance has sharpened interest in the uses and effects of masks in this kind of drama. It has long been known that certain characters in the mystery plays wore masks, but there has been relatively little discussion of the theatrical implications. This chapter aims to consider the performance effects of this masking. It seems that the use of masks might have some far-reaching consequences for the whole visual style of the mystery plays, and indeed might significantly affect the interplay of emotion and worship, the human and the divine, in the theatrical experience they offer.

Masks and Miracles

Before the English mystery plays, however, came a religious drama of which we know comparatively little: not the liturgical drama, which was first recorded in the England of the tenth-century Benedictine Revival, and which was still running in parallel with the civic plays in the fifteenth,1 but the miracles or ‘clerk plays’. As their name suggests, they seem to have been written, directed, and probably performed by members of the minor clergy,2 possibly in the churchyard, market-place, or outside the city walls rather than in the church.3 They were popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and their techniques may well have been taken over by the emerging civic drama. Several, though scattered, records suggest that they were played in masks. A famous story from the Life of St John of Beverley (c.1220) talks of a Play of the Resurrection in the churchyard, as a larvatorum, ut assolet … repraesentatio (‘a masked performance, as is customary’).4 This strongly implies that all the actors were masked, or else that masking was a characteristic part of the performance.

It is just possible that these were otherwise unrecorded professional travelling troupes, who used masks as a matter of course, possibly by long-term tradition.5 But the Manuel des pechiez (c.1300) associates both ‘miracles’ and masking with the clergy:

Vn autre folie apert

Vnt les fols clers cuntrové

Qe miracles sunt apelé.

Lurs faces vnt la desguisé Par visers, li forsené

Qe est defendu en decrée.6

The crazy clergy have invented another manifest craziness, which is called miracles. There they have disguised their faces with masks, the lunatics, which is forbidden in the Decretal.

The decrée forbidding masks is the 1234 Decretal of Gregory IX, which seems on occasion to have been used to suppress ordinary religious drama performed in church or churchyard as well as the disruptive masking of the Feast of Fools.7 The real situation seems irrecoverable: was all acting referred to as ‘masked’, even if only a few devils wore visors, in order to bring the activity under the meaning of the act? Or was earlier performance, even by the clergy, genuinely masked in totality? Robert Mannyng, translating the Manuel soon after it was written, does not mention the visers, which may well be significant; but the same passage was translated in the mid fourteenth century:

another opone folye they maketh. and folie clerkes habe fonde hyt up. that myracles byth called. there they habe here faces dyscolored. by visers the cursede men for hyt is defended in lawe the more is here synne.8

The use of ‘dyscolored’ for desguisé could suggest lack of familiarity with the custom, though it is likely to be simply the common conflation of masks and face-painting.9 But in a fourteenth-century sermon handbook, the Dominican John Bromyard associates actors in ‘miracles’ with masks: ludentes enim in ludo, qui vulgariter dicitur miraculos, larvis utuntur, sub quibus personae non apparent, quae ludunt (‘for those who play in the play which is called miracles in the vernacular use masks, beneath which the persons of those who play are hidden’),10 It may be that all these writers were, as we frequently find, simply copying earlier preachers without reference to what was happening in their own day; but Bromyard generally makes a point of using modern examples. Without further concrete evidence the case must rest here.11

Evidence, Purposes, and Effects

Evidence for the use of masks in the mystery plays in Britain is widespread but erratic. It comes first from scattered references in Guild records which, like most of the evidence for props and costumes, has been selected for us by chance. Many of the cycle plays for which we have scripts may have used masks, but only a handful of accounts and inventories from the guilds involved survive, sometimes dating from significantly earlier than the existing texts. There are no accounts at all which we can directly and confidently match with existing scripts.

Within the records random selection continues: unless a complete inventory of props and costumes for a play happens to survive, things tend to be recorded only when they are mended, or in some cases replaced. So we can see from the Coventry Smiths’ accounts that ‘the devyls hede’ and ‘herodes heed’ must have taken a battering each year, as they are repaired fairly regularly; the same applies to ‘the devells facys’ of the Coventry Drapers’ Doomsday pageant.12 But if God in that play was also masked, as seems probable by analogy with the ‘veserne gilted’ assigned to God in the York Mercers’ Doomsday inventory,13 then he must, being fairly static, have kept it immaculate, as it never turns up in the accounts at all. Another limitation of the Guild records is that they rarely describe either the masks or what they are made of.

If it is hard to be sure exactly which characters wore masks, it is even more difficult to estimate the effects of masking in the plays. We need to try to evaluate not only what happened, but also what attitudes were activated by the use of masks. Unfortunately we have almost no contemporary comment or criticism directly about mystery-play masks. This means we are mostly confined to speculation from the scripts, which is fraught with complications and uncertainties. If it were not for the records, we might be unlikely to notice from the texts alone that some of the characters were masked. But since there is so little external evidence of the assumptions involved we are thrown back largely onto these play texts, in spite of the difficulties of matching evidence and scripts.

One late contemporary comment on the mystery masks does survive. The ‘post-Reformation’ Banns for the Chester Cycle apparently replaced the earlier, Roman Catholic, Banns during the increasing Protestant hostility towards the plays during the second half of the sixteenth century.14 The new Banns comment extensively on the plays, showing a rather defensively apologetic attitude towards their ‘old-fashioned’ drama. One stanza specifically discusses the use of the gold mask for God. While this mask obviously raises unique concerns, the comments may throw light more generally on mystery-play masking.

The stanza seems a most seductive piece of evidence since, apparently for the first time, it talks in some detail about the purpose and effect of putting God into a mask. Its general drift is fairly clear, but the verbal details are slightly confusing. The audience is warned not to expect the sophisticated techniques of the modern stage. For then, we are told:

… shoulde all those persones that as godes doe playe

In Clowdes come downe with voyce and not be seene

ffor noe man can proportion that godhead I saye

To the shape of man face, nose and eyne

But sethence the face gilte doth disfigure the man yat deme

A Clowdy coueringe of the man, a Voyce onlye to heare

And not god in shape or person to appeare.15

The terms of this passage are not wholly easy to follow, since the exact significance and stress of ‘proportion’, ‘shape of man’, and ‘disfigure’ are difficult to determine. Disfigure at this period does not appear to carry its later connotations of ‘deform’, but a more neutral sense nearer to ‘un-figure’ or ‘alter the shape of’. The last three lines of the extract are perhaps the most potentially ambiguous. The sense seems to be: ‘since the gold face conceals the identity of the actor, think of it as if it were a cloud machine concealing the whole man, so that we only hear the voice of God coming from this cloud cover (or mask), and do not see God himself supposedly appearing physically on stage’.

It is wrong, the passage suggests, for any man to try to ‘act’ or imitate God, because no human being can ‘proportion’ the Divinity. But the problem can be averted if we think of the golden face as equivalent to a modern cloud machine which effectively conceals the actor, allowing a ‘voice of God’ to speak. This comparison urges that the mask, like a cloud machine, must be thought of as completely abolishing the man, the actor. We do not see him representing or pretending to be God, but only hear the voice in the golden face speaking God’s words. This seems to concur with dramatisations of divinity in certain other cultures, where the masked human performer presents, rather than represents, the deity. As John Emigh suggests, even with more obviously ritualised traditions of masked performance ‘to say that the performer represents or acts the part of [the] spiritual entity is to use a Western gloss for what is happening’.16 But the argument of the Banns goes a stage further. Even the mask itself, it suggests, is not representing God mimetically. It is an emblem or sign, like the cloud machine, which stands for God without actually imitating Him. That is why, even with the gold face, we do not see God ‘in shape or person to appeare’.

Interesting as this stanza is, it offers a view of the God-mask, and perhaps even of masked acting in general, which is only partially helpful in illuminating the medieval practice of the cycle plays. Its patent uneasiness about the appearance of God on the stage seems foreign to the mysteries, and in fact to almost all medieval drama. In spite of the obvious problems of performing divinity, a sense of impropriety in human actors playing God seems to be largely a post-Reformation development. Anxiety about ‘conterfuting or representing’ God through visual images, and especially by human impersonation, is a characteristic of the iconoclasm of the later sixteenth century.17 But during the Middle Ages generally there is little objection except from the Lollards; and even Wycliffe seems to accept that the theology of the Incarnation justified the use of images.18 Fifteenth-century iconography is insistently physically representational, and the portrayal of God on stage seems to have excited no more, if no less, controversy than the portrayal of God in pictures.19 God is anthropomorphised without apparent anxiety not only in the mystery cycles, but also in earlier morality plays like The Castle of Perseverance and Everyman.

Nor does this change overnight with the Reformation. John Bale’s mid-sixteenth-century plays, though violently anti-Catholic, introduce Pater Coelestis, Deus Pater, and Christ as characters, without apparent qualms, Christ even addressing the audience to invoke their devotion to himself.20 The fragments of the Protestant play Christ’s Resurrection (1530–60) also dramatise Christ, admittedly less problematic than the Father, inventing for him a non-biblical scene only alluded to in the Gospels.21 Even as late as (probably) the 1580s, the ‘part of God in a playe’ known as the Processus Satanae was copied.22 This play dramatises an investigation into the Redemption, prompted by Satan and carried out by the Four Daughters of God; so the copying of this actor’s part implies performance of a play which is not a cycle play with the excuse of tradition but nevertheless uses an actor to portray God without noticeable hesitation. The late Chester Banns therefore suggest a religious uncertainty about the use of masks for this purpose which, although characteristic of its own time, does not appear to have operated in medieval performances.

This leads on to the more general aspect of the Banns’ argument. The unease over the propriety of a human actor impersonating God, and the way the mask is justified, suggest a self-consciousness about masking itself. This is seen in the painstaking distinction that is made between the man who is the actor and the mask that is to conceal him. The words of the Banns, explaining the ‘proper’ reaction to this mask, imply that the audience, unless guided, are likely to look behind the mask and what it represents to the face beneath, and experience a tension between the two.

As we have seen in relation especially to courtly masking-games, such play between mask and face certainly did exist by the early sixteenth century. The early regulations condemning popular disguising and the descriptions of court masking entertainments both reveal a growing interest in the concealing properties of masks. The terms disguise and disfigure themselves suggest a recognition of the usual ‘guise’ or ‘figure’ beneath the mask. Such concern with mask as concealment or disguise has persisted in the post-sixteenth-century European theatre right until the present, the interest frequently focusing on the relationship between the mask and the face behind it. The audience is often encouraged to penetrate the mask to discover the person beneath. An alternative modern focus may be on the sense of trapping stasis the mask can impose on the character. By its very nature a mask implies lack of character development. While this may seem appropriate for the allegorical personifications of the morality drama, or the traditionally fixed biblical or moral roles of the characters in the cycles, it is something that modern drama has tended to find troubling, if fascinating, both dramatically and psychologically. The early-twentieth-century revival of interest in masks, and their use in plays by playwrights like Pirandello, Yeats, and O’Neill, concentrated on the fact of masking itself, as in very different ways did the masks and disguisings of the Tudor period.23

But the use of masks in the cycle plays seems to belong to a different tradition. As communal expressions of spiritual mythology, they come closer to ancient traditions of masking such as we find in some Classical, Oriental, and African popular religious theatre.24 Medieval god-masks do not appear to act as literal conduits for divinity, as in some kinds of religious masking. But neither do they depend on an active dynamic between the mask and the face beneath. As John Emigh suggests, the performer ‘takes on the exterior look of another, but makes little attempt to match this assumed appearance by internally identifying with the other’.25 Such traditions do not encourage their audiences to recognise a tension between the mask and the actor. The concentration is on the character who is presented by the mask – often a god, mythical hero, or evil spirit – not on its relationship to the wearer. Once the mask is on, the actor as an individual simply disappears behind it: only the character is left. This can be seen from both texts and performances of these dramas, as anyone who has seen the demonstrative masks of Kabuki theatre, Indian Ramlila, or perhaps even reconstructions of masked classical Greek plays will know. As John Jones remarked of the ancient Greek theatre, these masks are used to reveal, and not to conceal the face: ‘They did not owe their interest to the further realities lying behind them, because they declared the whole man. They stated: they did not hint or hide’.26 This seems much closer to the masking tradition of the mystery cycles. The texts of the plays suggest no self-consciousness about the masks at all, often not even an awareness of them. They demonstrate a character, or an idea: they do not conceal or disguise anything.

All this seems congruent with general medieval interest in emblem, sign, and figure. In the drama, as in painting, visual details are rarely simply decorative, and almost always semantically expressive, designed to explain ideas and reveal meanings. This is particularly clear in the allegorical use of ‘emblem’ masks, as the following chapter will show. But such use of visual symbols clearly carries over into things like the attributes for saints and apostles, which express ideas more than naturalistic facts. The visual and iconographic conventions associated with the biblical figures of the mystery cycles appear to have the same kind of explanatory function. When Pauper, in the fifteenth-century treatise Dives and Pauper, explains the image of the Virgin he interprets all the conventional iconographic features, even those we might assume to be naturalistic, as emblematically expressive:

Þe ymage of oure lady is peyntyd wyt a child in here lefght arm in tokene þat she is modyr of God, and wyt a lylye or ellys a rose in here ryght hond in tokene þat she is maydyn wytouten ende and flour of alle wymmen.27

Presumably this is also the function of the masks. They are used to express an idea rather than an actuality; and what is conveyed is an idea about the character, not about the performer and his relationship to the mask. When God, Christ, or the transfigured Apostles wear masks, we must assume these have the same purpose as the haloes worn in religious art by saints and angels. Dives and Pauper makes it clear that this purpose is the symbolic expression of ideas rather than a direct attempt to imitate appearance. The haloes signify not just ‘divine radiance’, but something more abstract. When Dives asks Pauper about the Apostles’ haloes, ‘Qhat betokenyn þe rounde thynggys þat been peyntyd on here hedys or abouten here hedys?’, Pauper replies, ‘Þey betokenyn þe blisse þat þey han wytouten ende, for as þat rounde thyng is endeles, so is here blisse endeles’.

Sometimes Pauper offers differing significations for the same visual conventions, as with the rich robes of the saints in paintings and statuary. When Dives objects, ‘Þey weryn nought so gay in clothyng as þey been peyntyd’, he replies, ‘Þat is soth. Þe ryche peynture betokeny3t Þe blisse Þat Þey been now inne, nought Þe aray Þat Þey haddyn vpon erthe’.28 Yet later he puts forward a different interpretation:

Dives: I suppose þat þe seyntys in herthe weryn nought arayid so gay, wyt shoon of syluer and clothys of gold, of baudekyn, of velwet, ful of brochis and rynggys and precious stonys … for Þey shuldyn an had mechil cold on here feet and sone a been robbyd of here clothis.

Pauper: Soth it is Þat Þey wentyn nought in sueche aray. Neuereles, al Þis may be doon for deuocion that meen han to Þe seyntys and to shewyn mannys deuocioun.29

The argument here acknowledges that this visual splendour is expressive not so much of the saints’ earthly material existence as of their devotees’ responses to them. If, as it seems, the masks of the cycle plays have a similar function, then Pauper’s words have particularly vibrant implications for the relationship between stage and audience. The power of the mask may be reception-driven, its relationship to the spectator more important than its relationship either to the wearer or to the character portrayed.

A particular feature of medieval theatre is that, since only some of the characters appear to have been masked, masked and unmasked performers share the same stage. The use of a mask in a play rather than a procession, a static tableau, or even a game, already enriches its signification: its power of expression is complicated by its involvement in speech and action. The interaction of masked and unmasked faces augments even further the ‘density of signs’ which Barthes identifies in theatrical performance, raising questions about the interplay of different kinds of acting and stage representation.30 Masks generally dictate particular kinds of stylisation in performance. While we know too little about medieval conventions of acting to judge the overall effect, it seems quite possible that the characteristics of masked acting combined and interacted with rather different modes.

This probability is confirmed by various other evidence. Guild records show that a good part of the visual effect of the mystery plays was deliberately non-naturalistic: the Virgin, even in the most ordinary activities, may appear in a crown;31 the Tree of Paradise is hung with figs, almonds, dates, raisins, and prunes as well as apples;32 Peter and Christ may wear gilded wigs; and Christ himself at the Resurrection may appear in a wounded leather body-suit under his red cloak, a suit which signifies nakedness rather than simply using the actor’s naked body. As with the masks, these visual details are expressive rather than gratuitously ornamental, concrete signs for various spiritual ideas. Yet the overall stylisation contains details which can themselves be domestic, homely, and familiar: the gifts given by the Shepherds to the infant Christ, or the ropes, hammers, and wedges used by the soldiers at the Crucifixion – themselves then codified as the Instruments of the Passion. Stylisation and visual sign ranges from the most formal and exotic, to the most ordinary and familiar.

Similarly the texts of the plays themselves seem to call for varying registers of acting. They can move from the stately oratory of God to the virulent colloquial abuse of Cain, from the moving seriousness of the Annunciation to the earthy comedy of Joseph’s Doubts, from the down-to-earth violence of the Soldiers to the highly formalised laments of the Maries, without any sense of discontinuity. Even within the same character the Shepherds can move from naturalistic grumbling to learned exposition, Mrs. Noah from vulgar irresponsibility to docile humility, without any noticeable unease. All this supports the evidence of the masks – that ornate stylisation deliberately coexists with apparent realism to form a composite style. This seems to be a characteristic of much folk theatre, and it appears that the cycle plays with their popular, communal, and seasonal elements, draw on those traditions as well as on more learned forms. As one of its semioticians has pointed out: ‘In the folk theatre the simultaneous use of the most diverse styles in the same play is a widespread phenomenon, a special theatrical device of form’.33 This also holds true for the mysteries: the use of masks is a significant element in their assured exploitation of diverse theatrical styles.

Masked Characters

Who wore masks in the mystery plays? M.D. Anderson seems right in saying that ‘they seem chiefly to have been used to denote extremes of Good and Evil’.34 By the fifteenth century they are worn mainly by God and the devils, together with some notoriously wicked characters.35 It appears that they were seldom used for ordinary humans: in the York Creed Play inventory Christ is distinguished from the Apostles by his larva aurata (gilded mask).36

The only play in which ordinary human beings are recorded as wearing masks is Doomsday. The York Mercers’ 1433 inventory gives ‘vesernes’ to the ‘ii gode saules’ as well as to the ‘ii euell saules’. But Doomsday is set in a cosmic arena, where human beings are clothed in the spiritual bodies of the General Resurrection, and their costumes and masks express the state of their souls.37 In the Coventry Doomsday play accounts they appear as ‘the white & the blake soules’, and it seems likely that the York Doomsday play also reinforced the black/white Judgement Day message by stylising the souls to match. From 1557 the Coventry accounts record a regular item ‘for blakyng the Sollys fassys’, a cheaper and perhaps more expressive way of creating the masked effect.38 This was not purely symbolic: popular belief seems to have held that the sins of the Damned would be reflected in the corruption of their risen flesh, whereas the Saved would share the claritas of Christ revealed in the Transfiguration.39 The souls are of a different order of being from when they lived on earth, and the masks help to set them apart from their surrogates in the audience.

Whether or not performances of miracles were fully masked, the mystery cycles for which we have texts were apparently not. Instead we have the interesting theatrical situation of masked actors performing alongside unmasked. It is worth considering separately each group of characters known to have worn masks, since each involves different issues. If we can establish what each might have looked like, we are better placed to understand the effects of the particular masks and their interaction with unmasked performers. This inevitably brings modern sensibilities to the medieval theatre: but in the absence of the crucial contemporary criticism it is the best we can do.

Devils

Devils, who turn up in many different kinds of medieval theatre, are the only characters who seem always to wear masks. Account after account plays variations on ‘for makinge ii denens heades’, ‘for peynttyng of the demones hede’, ‘payd for a demonys face’, ‘vi deuelles faces in iii Vesernes’.40 Mention of the devils’ visers slips casually into other writings: Wycliffe comments ‘Suche fendis with ther visers maken men to flee pees’.41 Hoccleve, putting words into the mouth of the dying man, makes him see ‘Horrible feendes and innumerable’ lying in wait for his miserable soul:

The blake-faced ethiopiens

Me enuyrone …

Hir viserly faces, grim and hydous

Me putte in thoghtful dredes encombrous.42

The mumming made to Richard II in 1377 included ‘8 or 10 arayed and with black vizerdes like devils appering nothing amiable’.43 Devils in all genres of theatrical performances seem to share the same appearance.

They were traditionally black.44 The Devil in the large-scale morality The Castle of Perseverance refers to himself as ‘Belyal the blake’, and rallies his ‘boyes blo and blake’ to the attack on the castle; when the little devils are driven away in Wisdom, Wisdom himself says ‘Lo, how contrycyon avoydyth þe deullys blake!’.45 The wicked souls in the York Doomsday lament that they are henceforth ‘In helle to dwelle with feendes blake’.46 Morally and spiritually, this black is the opposite of divine radiance. Historically, they seem to have been charred when they fell from heaven: ‘Fellen fro the fyrmament fendes ful blake’.47 Arrived in hell, the York Lucifer cries, ‘My bryghtnes es blakkeste and blo now’.48 In French drama devils, if not wearing visors, had their faces blackened like the Coventry ‘blakke soulys’, and it seems likely that minor English devils looked the same.49 Devils are often compared to Ethiopians, as in the Hoccleve quotation above.50

It is not specified anywhere precisely what the late medieval devil’s ‘viser’ should look like: stage directions usually content themselves with saying ‘here xall entyr a dylle In orebyll aray’, or ‘Here enteryth Satan … in the most orryble wyse’, or by implication ‘Here ANIMA apperythe in the most horrybull wyse, fowelere than a fende’.51 Provided the effect was ‘the most orryble’ he could produce, the medieval mask-and costume-maker was presumably free to create whatever his imagination and his materials would allow. Allardyce Nicoll prints a whole page of ‘medieval’ (in fact largely eighteenth-century, but presumably traditional) Austrian devil-masks, each with its own particular wise of being ‘orryble’.52

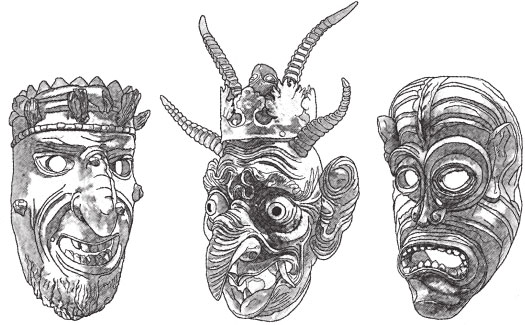

FIG. 7: Eighteenth-century wooden masks, Oberösterreichische Landesmuseum, Linz

The French devil of the Avignon Praesentatio of 1385 was to be dressed tali ornamento sicut eidem decet turpissimo et abhominabili, cum cornubus, dentibus, et facie horribili (‘in the type of costume that befits him, extremely nasty and repulsive, with horns, teeth, and a horrible face’).53 Horns and teeth emphasise the predatory, feral role of the devil, seeking whom he may devour: many devil’s faces are based on those of wild animals and most feature something of this aggressive spiky quality. Horns seem almost mandatory: they were presumably easily acquired from the local butcher’s. Cows’ and rams’ horns seem most popular, though there are local variations: Austrian and Swiss devils, for example, often go for the Alpine goat. There are also one-horned devils, like those in the Triumph of Isabella.54

FIG. 8: Devils from late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth-century woodcuts

Besides horns, most pictured devils also have large animal ears, either erect, of any length from cat to donkey, or drooping and spaniel-like. They may also, especially in woodcuts where it suits the technique, have the up-blown quiff of hair flaring from the forehead which is a scaled-down version of the Romanesque devil’s wild but stylised coiffure.55 A large red tongue adds to the animal features. Étienne de Bourbon tells of a woman who saw a devil in the shape of a hideous tom-cat, about the size of a large dog, habens … oculos grossos et flamentes, et linguam latam et longam et sanguinolentam et protractam usque ad umbilicum (‘with great big fiery eyes, and a wide, long, blood-red tongue which stretched down to its navel’).56

Many devils are also fanged, with tusks coming upwards from the lower jaw. In masks the jaw itself could be wired to snap: an Austrian devil-costume illustrated by Allardyce Nicoll has an almost crocodile jaw which seems to have worked in this way, and the Dorset Ooser (a mysterious but distinctly demonic mask, made of wood) was provided with a lower jaw which was moveable, and gnashing teeth, the jaw being worked by a string’. It would seem that the secundus demon of the Towneley Doomsday ‘girned and gnast’ like this.57 Lucifer in the Fall of the Angels window in St Michael Spurriergate, York, is distinguished from an angel of light by his horrible gappy teeth. Nicoll also points out how many of the surviving devil-masks appear to sport large and conspicuous warts. The Dorset Ooser also had ‘Between the eyebrows … a rounded boss for which it is difficult to find an explanation’. It could be a well-developed version of the devilish wart.58

FIG. 9: The Dorset Ooser

Craik suggests that one of the most prominent features of the morality-play devil was his ‘bottle-nose’:

An important characteristic is an ugly nose, large and misshapen – he swears by his crooked snout in the Newcastle miracle of Noah – and in some interludes the vice ridicules it, saluting him in Like will to Like as ‘bottel nosed knave’, and in Susanna as ‘crookte nose knave’.59

Presumably the nose is being compared to a bulbous leather bottle: but the majority of devils in pictures have long curved noses and the OED tentatively suggests (though it rejects) an etymology from bytel, ‘cutting instrument’. In mask-making, the nose is the easiest feature to exaggerate, and usually the one which determines the character of the whole face.

The more sensational devils could be fitted up to breathe fire, smoke, and squibs. Most of the devils in the Bourges Monstre, the procession and Banns for the Acts of the Apostles performed in 1536, emitted feu par les narines et oreilles, et tenoient en leurs mains quenouilles a feu (‘fire from their nostrils and ears, and held in their hands “fire-distaffs” [hollow batons filled with gunpowder]’).60 Belyal in The Castle of Perseverance has ‘gunnepowdyr brennynge In pypys in hys handes and in hys erys and in hys ars whanne he gothe to batayl’.61 Playing the devil clearly had immediate and practical dangers. In a Provençal producer’s text from the end of the fifteenth century there are detailed instructions on making a devil’s fire-breathing mask: the actor was advised to carry goose quills full of a sulphurous inflammable liquid which he blew across a burning coal fixed inside the mask, much like modern fire-eaters.62

One particularly interesting effect which clearly fascinated medieval mask-makers can be glimpsed in the York Mercers’ 1433 inventory: ‘iii garmentes for iii deuells vi deuelles faces in iii Vesernes’.63 In the Bourges Monstre of 1536, Lucifer, seated on top of Hellmouth and dressed in a bearskin each hair of which was spangled, avoit un tymbre a deux museaux (‘had a mask with two muzzles’).64 It does not say where the two faces were in relation to each other, only that il vomissoit sans cesse flammes de feu (‘he spewed forth flames of fire without ceasing’). Double-faced masks can be produced with faces front and back (the easiest), facing left and right (making eye-holes difficult), or obliquely, sharing a pair of eyes. They can be very striking when static, and were used in disguisings and moralities to create stage emblems of various ambivalent or vigilant moral characteristics,65 but they depend on movement for their full effect. To have a devil turn its back but still be looking at you is profoundly unsettling, suggesting a malevolent and supernatural watchfulness.

Although we have no contemporary pictures of a two-faced devil, multiple faces are common: many pictured devils bear extra faces on elbows, knees, bellies or arses, or beneath tails, thus combining monstrosity and perversion with comic humiliation of God’s image in the human face.66 They also open a range of unsettling mimetic possibilities for a supple performer: supernumerary faces can ‘talk’ to each other, or even to members of the audience.67 Judging from art, however, the obvious pornographic possibilities do not seem to have been as much exploited as one might expect.68

FIG. 10: Early Romanesque Devil Autun, 1120–1130

Where did the stage devil come from? There seems a powerful possibility that the mask, and probably the costume, of the play-devil was descended from the larva and ragged or hairy costume of the early folk maskings. This is not a new suggestion: a whole generation of earlier writers on folk masking has made the same assertion – but like us, has failed to come up with any more convincing evidence than a strong impression.69 However, both linguistic and iconographic history is suggestive.70 Devils as we know them hardly appear in art until the eleventh century.71 Pre-Romanesque devils are angels that have been caught in a nuclear holocaust: winged, humanoid, but black and often shrivelled.72 Romanesque devils are still winged and scrawny, but the emphasis is now on their horrific larvae, and they tend to be tufted with hair as well. The official art-historical explanation is that they are descended from the classical satyr;73 but this does not explain the larvae, or why it should have been the satyr which was adopted at this date as a figure for the devil. If there already existed a popular hairy figure with whom the devil could be identified, it seems a more plausible model.74 It is quite possible that we have here a genuine influence of masking on art. (It is also interesting that in the stage directions in the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman Jeu d’Adam, costumes are specified for everyone except Satan and the devils.75 It may be that already these were the only characters whose costumes were fully familiar.)

FIG. 11: Pre-Romanesque Book of Kells Romanesque Winchester Psalter Gothic St Martin’s, York

From the Romanesque devil there develops the familiar ‘Gothic’ devil, hairy (often virtually indistinguishable from the wild man or woodwose), horned, fanged or taloned, and goggle-eyed. The devil from the St Martin window in St Martin Coneystreet, York, can serve as a general example of an English devil of the fifteenth century. He is more humanoid than animal-like, but he has animal features. He has even lost his wings. Such a devil is more easily transferred to the stage than the fantasy creatures of Bosch or Bruegel, and seems likely to come closest to a mystery devil-costume.

If we follow the folk-masking strand we can see a parallel change in identification. In themselves the costumes worn by the early maskers – the animal horns, hairy pelts, blackened faces, rags and tatters – are not necessarily diabolical: no more so than those of any nineteenth-century English folk play. But the choice of mask will finally determine how the amorphous figure is read. We do not know what the monstra larvarum actually looked like, or how they differed from the capita bestiarum: or indeed what, if anything, they were meant to represent. There have been conjectures enough, but all we really know is that they were frightening.76 At some point, possibly in the eleventh or twelfth century, they are perceived by clerical writers, if not necessarily by the participants themselves, as representing daemones, by now classed as evil spirits. In the context of performance in church, liturgical or anarchic, the daemon became a devil. By the later Middle Ages, maskers were explicitly identifying at least one type of carnival disguise as a devil costume:77

I haue harde that a certayne man was slayne

Beynge disgysed as a fowle fende horryble

Whiche was anone caryed to hell payne

By suche a fende, which is nat impossible

It was his right it may be so credyble

For that whiche he caryed with hym away

Was his vysage: and his owne leueray.78

Images of the Schembart Carnival, for example, confirm that the participants are dressed up in what is by now distinctive devil attire. Moralists from Brant’s Ship of Fools onwards accuse carnival maskers of doing the devil’s work in the devil’s own clothes: ‘under theyr deuyls clothynge as they go The deuylles workys for to commyt also.’79

If the devil of the mystery plays is, as it appears, related to, identified with, or descended from what had become a devil-figure of popular masking, this will condition the way in which the medieval audience apprehended them and their masks. It may also enable us to use some of the reactions towards the masking-game devil as a measure of the reactions towards devils in plays. Whether mystery-play devils deliberately imitated the figures of popular masking, pointedly turning the popular masks into the villains of the biblical narrative, or whether the costume was merely the obvious and accepted available convention for something non-human and frightening, we shall never know. Whatever the reason, it would have been a clever and shrewd move. People enjoyed masking, but it could get out of hand; wearing the same costume but to play the devil in a mystery play kept everything within bounds. One still clearly enjoyed playing the devil: plays like the Towneley Doomsday with its protracted diabolical japing suggest that the audience were meant to enjoy it too. But the officially restrictive attitude to this kind of masking could be safely reversed: both theatrically and theologically the mystery devils have the curiously equivocal role of Evil willy-nilly playing the agent of Good. One may not have approved of them, but they were now placed and confined within the right moral and narrative structure.80

Can we tell what effect such masked devils would have on the audience of a mystery play? The fact that they seem related to the devils of carnival masking does not necessarily mean that they would have the same impact: the context is crucial and the devil of the mystery play operates in a moral framework which would considerably alter his profile. However, some similarities seem to have been deliberately exploited. Richard Axton points out how the early devils of the Jeu d’Adam seem to enjoy a special relationship with the audience, a freedom to roam through the open spaces (per plateas) between the structures and to run in among the audience.

Running is their characteristic activity. The demones are purveyors of entertainment as well as objects of doctrinal terror … always full of energy and hilarity, dancing with glee at the imprisonment of Adam and Eve, ‘shouting to one another in their joy’ – apparently ex tempore.81

Behaviour like this is more discernible in the texts of moralities than of English mystery plays.82 But the script does not tell us everything: it would seem almost impossible for the devils especially of processional street plays not to set up a relationship with the audience. The various Doomsday plays, particularly Towneley, do suggest such an interaction with the spectators, as does any play in which the devils come to take away their prey: ‘Harrow, harrow, we com to town’.83 The 1615 van Alsloot painting of the Triumph of Isabella gives a very good picture of how devils could be used as in processional performance as stitlers (crowd controllers), harassing ‘shrewd boys’ who got in the way with whips and ‘squertes’ [PLATE 21]. Similarly in the sixteenth century, Barnaby Googe’s translation of The Popishe Kingdome says of carnival maskers:

PLATE 21: Devils with whips and squirts chasing ‘shrewd boys’.

Denis van Alsloot The Triumph of Isabella (Brussels 1615), detail. Theatre Museum, Covent Garden (Victoria and Albert Museum). © V&A Picture Library.

PLATE 22: Maugis dresses in devil costume. Renaud de Montauban (mid fifteenth century).

Paris: Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal MS 5072 fol. 28r. © Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal/Bridgeman Art Library.

But some againe the dreadfull shape of devils on them take

And chase such as they meete, and make poore boyes for feare to quake.84

Mystery devils appear to behave much like the devil of popular masking. As we have seen, the disguise of Carnival confers licence: the masker being unrecognised, cannot be held to account for what he does. The audience may well be used to seeing creatures dressed like this behaving like this, and to allowing them liberties which they would not accept from a normally-attired fellow citizen. The actors in devil-costume are representing creatures an essential part of whose nature is licence.

But while the devils may be enjoying themselves, gaudentes et tripudiantes, one can, as many critics do, overemphasise their comic side.85 The belief that a personified devil will be merely comic seems a post-Reformation assumption. Although as Emigh points out ‘playful indulgence in the demonic’ is a feature of devilish masking in many cultures, allowing for ‘a kind of jocular intimacy with the powers of destruction’, that playfulness loses its point if the power of the evil spirit is not primary.86 The ambivalent interaction of humour and fear, delight and awe, is well expressed through the mask. The relationship of a masked devil with the audience will always have a sinister quality: it is something more than good-natured fun. As audiences of modern productions will know, a devil-costume is highly concealing: the suit and head form a totally enclosing carapace under which the actor completely disappears except for voice and possibly eyes. At most, you are aware that there is someone in there, but you cannot know who. A fifteenth-century illustration from the romance of Maugis d’Aigremont demonstrates the effect very well [PLATE 22]. Maugis is disguising himself as a devil in order to recapture the magic horse Bayard. On the left he is conspicuously a man dressed in a devil-suit: the cleric holds the headpiece. The costume is a dark and hairy, and the inside of the mouth fiery red; the teeth are white, with eyes, horns and flame-like hair picked out in gold. On the right, Maugis has put on the head and ceases to be a man dressed up: he has become a completely alien being.87 Any laughter generated by such a creature will be sharply spiced with terror.

In direct exchanges with the spectators the mystery devil can draw on the unsettling ‘mumming’ encounter of the masked with the unmasked. But with the masked person clearly defined within a Christian framework as a devil, the relationship becomes more decisively that of tormentor and victim. The mask and costume, with the bestial teeth and claws, emphasise the predatory intent and the alien unpredictability of the creature. If this devil decides to play with you, it is like a cat playing with a mouse: you cannot take the initiative but must accept the game-rules he establishes. There is undeniably a comic role. The devil’s freedom to indulge in the forbidden, the grotesque, the excessive, and the trivial in language and action generates delight and laughter: but the laughter is always uneasy. In sermons, when we are invited to laugh at the devil, it is usually at his discomfiture: when he falls off a lady’s train into the mud, or accidentally bangs his head on the wall.88 When such comic discomfiture happens on stage, the audience can laugh because they are safely insulated from the devil, usually triumphing through someone stronger than themselves: God, or Christ. Plays of the Fall of Lucifer or the Harrowing of Hell where Satan is worsted by his divine adversary, promote such laughter. But where the stage devils appropriate carnival behaviour the interaction is more dangerous. If the devil moves from the sphere of the dramatic narrative to play directly at you, you may laugh, but the laughter will remain nervous, as there is no longer a barrier between you. Even if you have invited his attention, he still has the advantage of inscrutability. If he is tormenting someone else, like the ‘shrewd boys’ in the Isabella picture, the laughter is still potentially nervous, as he may turn on you next. All actors and many audiences know this is a powerful theatrical strategy. In the context of the mystery plays it could be harnessed for theological and spiritual ends.

When the spectators are not directly involved in the action, but watching the devil manipulating characters safely on stage, what impression is created? Stage-devils are of necessity humanoid, and theologically the effect ought to be one of humanity warped. This may happen in some plays, notably the Falls of the Angels and of Man; but usually the carapace effect of the devil-suit and devil-head tends rather to emphasise the otherness of the devil. He did and was meant to frighten. You do not suggest ‘orebyll aray’ unless you intend to produce horror. After the devil has gone quietly in to Pilate’s Wife in N. Town, she comes rushing out ‘makyn a rewly noyse’ and ‘leke A mad woman’, saying, ‘Sethyn tyme þat I was born Was I nevyr so sore a-gast’.89 In the York Death of Mary, the Virgin prays especially that she shall not see the devil at her deathbed (as Hoccleve’s dying man did, and as most medieval people expected to). Christ replies that he cannot grant her this:

But modir, þe fende muste be nedis þyne endyng

In figoure full foule for to fere þe.90

It is unlikely that such stage-characters were meant to be frightened, and the audience to remain unmoved. If there was laughter, it was likely to be the laughter of self-reassurance. To suggest, as Allardyce Nicoll does, that ‘these devils, for comic purposes, appeared “in orebyll aray’”91 is to oversimplify; horror films, which can also provoke laughter, are not simply comedies. Even in modern productions where the audience has a quite different spiritual context, fully costumed and masked devils seem to generate at least as much fear as they do laughter.

The alternative means of deforming the devil’s face was apparently blacking-up. Technically this has much the same effect as masking. Painting the face any uniform colour flattens the features, erasing the small details of planes catching the light and changes of colour which give a face expression. It takes the face one step towards inscrutability. Black was also not the colour of face that a medieval Northern-European expected to see, and therefore must have given the initial shock of the unexpected.92 A human being with a blackened face would be both unnatural and unreadable. On a European face the blackening intensifies the whites (or yellows) and reds of the eyes, the red of the inside of the mouth and nostrils, and the white of the teeth by contrast, so that they become more vivid than normal. It also upsets the balance of colour and texture between face and hair, so that the hair, paradoxically, looks false.93

But the meaning of such a blackened face depends on its context. Accounts of past black-faced masking show that it could be read as impersonation of the dead (by the very early maskers); as sordidatio … faciei (dirtying the face) by the disapproving Church (and incidentally by the later folk play, which calls one of its characters ‘Dirty Bet’); as ambassadors from some exotic land, ‘Moreskoes’ or ‘nygrost or blacke Mores’, in the court maskings.94 If the figure is a devil, it will communicate menace or moral blackness. If it is a damned soul, however, as in the blackened faces of the Coventry Doomsday, the blackness becomes a shocking human disfigurement, as of the badly burned we hope only to see on safety posters. It is something which both is and is not ourselves. As a damned soul it may also convey a sense of pathos and helplessness, possibly because unlike a fixed mask it is halfway between impassivity and communication. The mask worn by the devil can, as we saw, affect spectators differently in different dramatic and social contexts. The blackened face is a very good example of overlap and difference, the flow of convention from one activity to another, and the complexity with which such a sign can be interpreted.

Humans

In the English mystery plays a few, notably wicked, human characters also appear to wear masks or face-paint. Evidence is too sparse to be sure how far this extended, and whether these masks were surviving traces of fully masked ‘miracles’, or of earlier processional characters.95 We find that on some occasions Herod and the Tormentors were masked, although not apparently Annas, Caiaphas, or Pilate. There is no information about Cain, Pharaoh, Antichrist, or the other sub-demonic figures. In fact far too little information survives altogether about human characters in the plays, and it may well be that because Chester and Coventry both happen to provide Herods, his part in this masking has assumed an undue prominence.

However, a striking amount of attention is paid to Herod’s face or viser. The Coventry Smiths, who played the Passion, paid in 1477 ‘for peyntyng … Herodes face’ and in 1516 ‘for peyntyng & mendyng of herodes heed’. Similar entries appear for 1547, 1554, and possibly 1508, where the item is ‘for colour and coloryng of Arade’.96 (A reference in the Beverley records to ‘black Herod’ may imply that there he was painted black.)97 In Coventry in 1499 it would seem that not only Herod was made up or masked: ‘Item paid to the paynter ffor peyntyng of ther fasses’. Much the same entry appears in 1502, and in 1548, where it is ‘payd to the paynter for payntyng the players facys’.98 It is not specified how many players were painted; but the Chester Shoemakers in 1550, for their extended play which seems to have taken in most of the Passion, paid ‘for geyldeng of godes ffase & ffor payntyng of the geylers ffases xijd’ (the ‘geylers’ were ‘the geyler’ and ‘the geylers man’: Annas and Caiaphas appear in the cast list, but not Herod). In 1558 the Shoemakers ‘payd ffor mendeng the tormentors heydes’, which could refer either to wigs or masks.99

PLATE 23: Grotesque helmet presented to Henry VIII by the Emperor Maximilian. The spectacles are a later addition. Royal Armouries, Leeds: IV 22.

© The Board of Trustees of the Armouries.

The presumption is that the Tormentors and Herod were masked or painted in order to make them look sub-demonic. There is no verbal evidence for this, but some pictorial: the Holkham Bible Picture Book, for example, makes its tormentors snub-nosed, pock-marked, and bestial-looking. A window from Norwich shows a gaoler apparently wearing a mask with a pig’s face, snout, gappy teeth, and all.100 Herod himself is frequently linked with the devil, both in the play texts and by commentators. A sermon of Leo I observes that the devil, having influenced Herod at the Slaughter of the Innocents, now imitates him; and this was slightly misquoted in the widely influential Catena aurea of Thomas Aquinas as Herodes etiam diaboli personam gerit (‘Herod, indeed, wears the mask of the devil’).101 This suggests a commonly held attitude that would coincide well with either a grotesque mask or black face-paint. The Coventry Herod also had a ‘Creste’.102 If this crest, which had ‘plates of iron’, gold foil and silver foil, was part of a helmet, it is marginally possible that the face was in actual fact a helmet visor, such as we have seen in the grotesque or characterised mask-visors of sixteenth-century tournament games.103 Herod’s ostentatiously irascible character and his predilection for sword-flourishing would suit such a grotesque helmet: but we shall probably never know if he wore one.

Putting human characters in masks clearly involves different problems and effects from the masks of devils. Since devils, like God, clearly belong to a different order of being, it seems neither surprising nor disconcerting that their non-human quality should be demonstrated in masks. But Herod and the gaolers, being human, offer a different case. A mask will inevitably set the wearer apart from the unmasked players. The interactions of a mobile human face with a static mask or inexpressive face-paint, whether grotesque or naturalistic, tend to produce striking and often sinister effects. If Herod and the tormentors are so distinguished, they are apparently given a different status from the other characters. The difficulty is compounded by uncertainty about what the masks actually looked like. Although probably bestial or devilish, we do not know quite how extreme they were. If they are devils’ faces, then a diabolic nature is imposed on all the wearer’s words and behaviour. Gaolers in masks like this could not play the role of excusably ignorant humanity that the tormentors of some Passion plays are thought to carry.104 Yet if the masks are almost human, they may combine even more oddly with the unmasked faces of the other characters.

One of the chief difficulties in estimating effects is the lack of correlation between existing texts, and the references to masks in the records. Even when references appear to be approximately contemporary with the play manuscripts, we can never be wholly certain how the surviving text relates to the masks mentioned in the Guild accounts. However, it seems vital to look at those play texts where it appears likely that masks were worn, for this is our only means of speculating about the effects.

One of the few examples of play-text-plus-reference is the Chester Coopers’ pageant of the Trial and Flagellation, where ‘Arrates vysar’ was mended in 1574.105 There are no references to masks for the other characters. The surviving text of the Chester Coopers’ pageant is interesting, even puzzling, if we approach it assuming that its Herod was masked. He has a far less pronounced ranting manner than in many other Herod plays, and is consequently far less overtly associated with the forces of evil. On the whole he appears relatively controlled, and even fairly reasonable in his interrogation of Christ. The only indication of the traditional devilish ranting is the one line ‘Alas! I am nigh wood for woo’.106 Apart from this his general manner is one of suave politeness:

A! Welcome, Jesu, verament! …

I pray thee, say nowe to mee,

and prove some of thy postie,

and mych the gladder would I bee …

for Pilate shall not, by my hood,

do the non amys.107

If Herod is wearing a devilish mask then this moderately reasonable tone is presumably transformed into a sadistically ironic game, as the courtesy of the words is belied by the evil of the face. Yet there is no indication in the lines themselves that this is intended. Pilate, for whom there is no record of a mask, is similarly reasonable, and the mildness of his approach does not seem to be intended cynically. Yet if Herod is wearing a mask, and Pilate is not, then the apparent similarity of their attitudes would be transformed on stage into a striking contrast.

Interestingly Annas and Caiaphas, who from the records do not appear to be masked, are far more aggressive, ranting, and ‘devilish’ in manner than Herod. If indeed Herod alone wore a mask in this version of the play, then it does appear to have been used for deliberate, and quite subtle, theatrical purposes. If this mask is a grotesque or demonic one, then it noticeably alters the effect of his part as it is written; if not, it is hard to see quite why he should be wearing it at all. One possible technical reason may be that in this play Pilate and Herod were doubled, which would require an extremely quick change: the 1571 expenses read ‘payde for the carynge of pylates clothes vjd’, the 1574 ‘paied vnto pylat and to him that caried arrates clothes & for there gloves vjs vjd’.108 ‘Arrates vysar’ would thus be a helpful disguise for the doubling; but any such practical purpose would make no difference to the theatrical effect of the mask.

The Chester Shepherds seem to be the only potential exception to the general evidence that masks or make-up on ordinary people denote evil or disfigurement. But this depends on the interpretation of the 1571/2 record entry ‘Item for payntes to bone the pleares’.109 If ‘to bone the pleares’ means ‘to make up the actors’ the shepherds may have painted faces. The Coopers’ accounts of 1574 use the word bowninge with its opposite unbowninge in the general sense of ‘get ready’, but is not sufficiently precise to allow deductions.110 In the script we have at least two of the players are bearded, Joseph conspicuously:

His beard is like a buske of bryers

with a pound of heares about his mouth and more.111

The 1575 accounts show that they paid ‘for the hayare of the ij bardes and trowes cape’: the ‘payntes’ may therefore have been for making Joseph and Primus Pastor up as old men.112 But the record evidence is altogether too scanty and random to judge.

God and the Angels

At the opposite end of the scale come the heavenly characters: God and the angels.113 Traditionally, God is masked or painted in gold. Besides God’s larua aurata (‘gilded mask’) in the York Creed Play, we also have the York Mercers’ 1433 ‘Array for God … a diademe with a veserne gilted’, and the Chester Smiths’, and Cordwainers’ ‘for gildinge of Gods face’.114 The mask, or the gilded face, is clearly an emblem of divine radiance: God revealed in His Godhead. ‘His countenance was as the sun shineth in his strength’ says Revelation 1: 16, while Peter in the York Transfiguration play, echoing Matthew 17: 2 resplenduit facies eius sicut sol, vestimenta autem eius facta sunt alba ut nix, says:

His clothyng is white as snowe,

His face schynes as þe sonne.115

The Transfiguration was clearly a spectacular transformation scene. In the 1501 Passion of Jean Michel at Mons, Jesus goes ‘into’ Mount Thabor and comes out again with une face et les mains toutes d’or bruny Et ung gran soleil a rays brunys par derriere (‘a face and hands all of burnished gold and a great sun with burnished rays behind’).116 Une face presumably means a mask, as there would hardly be time to gild his face or to restore him to normal afterwards; presumably les mains are gilded kid gloves. At Revello this effect was enhanced by reflecting light from a polished basin onto the face of the transfigured Christ.117 There would certainly be time in the York Transfiguration play for a similar change.

The Mons Passion also painted the angel Raphael’s face red for the Resurrection scene, so as to represent the Gospel Erat aspectus eius sicut fulgur (‘His face was like lightning’: Matthew 28: 3): Nota d’ycy advertir ung paintre de aller en Paradis pour poindre rouge la face de Raphael (‘Remember to warn the painter here to go to Paradise to paint Raphael’s face red’).118 There is no evidence from the Coventry Resurrection accounts (the only full ones we have) that English angels were painted like this. But the thirteenth-century Ingeborg Psalter shows the Angel at the sepulchre with a face similarly painted red; it also shows Christ at the Transfiguration with a gilded face.119 One or two stage directions in the liturgical drama show attempts to produce the same effect using a red veil: the (undated) Narbonne Visit to the Sepulchre printed by Young gives the direction:

Quibus dictis, sint duo pueri super altare, induti albis et amictibus cum stolis violatis et sindone rubea in facies eorum et alis in humeris, qui dicant Quem quaeritis in sepulchro …120

These words having been said, let there be two boys above the altar dressed in albs and amices, with violet stoles, and red muslin over their

faces and wings on their shoulders, who are to say, ‘Whom do you seek in the sepulchre …?’

Another Quem Quaeritis from an unidentified French monastery of the thirteenth century, although ambiguous, seems to specify a similar effect:

… duo pueri stantes iuxta altare, unus a dexteris, alius a sinistris, albis induti, rubicundis amictis capitibus et vultis coopertis, cantando dicant versum Quem quaeritis in sepulchro, o Christicole?121

… two boys standing near the altar, one at the right one at the left, dressed in albs, their heads and faces covered with red amices [or with red amices on their heads and their faces covered] who shall sing this verse, ‘Whom do you seek in the sepulchre, o dwellers in Christ?’

Masks and painted and veiled faces are used to replicate biblical texts literally, in the same way as the Psalter artist.

These instances all address moments of transformation or apparition. But the gilding, or silvering, of faces is also used to signify divine radiance as a permanent characteristic. At Henry V’s triumphal entry into the City of London after Agincourt, he was greeted at London Bridge by:

… innumerosi pueri representantes ierarchiam angelicam, vestitu candido, vultibus rutilante auro, alis inter-lucentibus et crinibus virgineis consertis laureolis preciosis.122

… innumerable boys representing the hierarchy of the angels, clad in pure white, their faces glittering with gold, their wings gleaming, and their youthful locks entwined with costly sprays of laurel.

An earlier pageant, for the Reconciliation of Richard II with the City of London in 1392, presented God the Father seated above the hierarchies of the angels:

Supra sedebat eos iuvenis quasi sit Deus ipse:

Lux radiosa sibi solis ad instar inest.

Flammigerum vultum gerit hic niveas quoque vestes,

Supra ierarchias ille sedet celicas.123

Above them [the angels] was sitting a young man representing God himself: a radiant light, in appearance like the sun, was his. He bore a blazing face and snow-white robes: he sat above the heavenly hierarchies.

The angels also had glittering faces: Sicque micant facies iuvenum tam in hiis quam in illis (‘Thus the faces of the young men sparkled, both these and those’). Painting and gilding seems accepted as representing the permanent state of transcendence.

The gold-faced God is an aspect of medieval theatre that is rarely questioned, but it is not clear where the idea of gilded masks came from. Apart from the two red-veiled angels in the liturgical pieces, it does not seem to have been an effect of the liturgical drama, where God rarely appears in propria persona. When He does, attempts to convey divine radiance usually give Him a crown; just as the radiance of the angels at the Resurrection can also be symbolically represented by carrying a candelabrum.124 We do not know what God may have worn in the early masked ‘miracles’. There is sufficient evidence in (mostly fifteenth-century) art to show that a golden face was one of the ways in which painters and glaziers showed the divinity of God: but not enough to show that the plays must have copied the art (or, as M.D. Anderson suggests, vice versa).125 It is possible that the figure is a direct representation of the sun-shining face in the first chapter of the Book of Revelation: Gordon Kipling suggests that the shining faces of the street pageants of Royal Entries were elements of an Advent pattern suggesting the Second Coming, but in the mysteries the image is more generalised.126

Perhaps the mystery plays simply re-invented a convention that seems natural to the religious drama of other cultures, that of masking its divinities to mark them out from ordinary human beings. The use of God-masks is a widespread phenomenon throughout the world, and one that seems extremely powerful in religious drama, as well as religious rituals.127 There is clearly something about a masked face that conveys a sense of ‘human-like but more than human’ that is particularly appropriate to the representation of anthropomorphic divinities of all sorts, as the use of God-masks in cultures as diverse as North and South American, African, and Asian demonstrates. So close is the connection between the presentation of God and the use of masks that in many societies the mask itself, at least as used in rituals, embodies or becomes the deity rather than representing it.128 It may be this apparently deep-rooted sense of appropriateness that makes the use of the golden mask for God the Father in the mysteries seem so acceptable. For God in Heaven to have a golden face or mask is both impressive and natural, since he is clearly separate from and above mankind. The mask’s inscrutability is translated as a sign of God’s impassibility and omniscience; the necessary deliberation of the actor’s movements conveys authority.

It can also generate a surprisingly powerful theological force. The Chester Banns remark how the distractingly human personality of the actor is abolished by the mask leaving only the voice, which can be perceived as the creative Word. The strongest and most unexpected theological effect of recent experiments in masked production has been the illumination of the concept of the Trinity. Late medieval artists were much exercised over how to represent a God who is both Three and One. Their solutions ranged from the geometrical (the so-called ‘Arms of the Trinity’) to the anthropomorphic (the Three Persons as three humans, either identical in appearance or varying according to our different experience of each). Unusually in the mystery plays, the N. Town Mary Play follows this last strategy, calling for the Three Persons of the Trinity to be onstage at the same time for the Parliament of Heaven. It is possible to emphasise difference, presenting them as the familiar Economic Trinity, Father as the Ancient of Days, Son as the Christ, and the Holy Spirit as a youthful version of the Son.129 But another route, taken in a recent production, is to dress and mask three actors identically.130 The masks confer instant anonymity: heaven, already full of unrecognisable masked angels, suddenly focused upon three identical persons, remote, hieratic, and golden, enthroned side by side. Not only were the three indistinguishable, but the masks made it impossible, when they spoke, to tell from which actor the voice was coming. They appeared to be speaking as one, but with individual voices. In the debate, each speaker’s gestures drew the audience’s attention (an almost ventriloquial effect),131 but at rest, the effect returned. There could not have been a better demonstration of ‘þis is þe assent of oure Vnyté’.132

The Parliament of Heaven takes place on a cosmic level, in which all the characters are embodiments of spiritual beings or abstractions. The masking effect may be complicated when God descends and interacts directly with men: with Noah, or with Adam and Eve as the Father with (possibly gilded) ‘face and heare’ does in the Norwich Grocers’ Creation play. Yet the use of a mask in such situation could add immeasurably to the power of the scene. The masked actor moving among unmasked figures automatically gains an authority and a mystery which is wholly appropriate for the divine/human relationship. In fact a mask moving among open faces can create an impression of divinity on stage without any help from the words that are spoken.

Modern audiences still find it easy to accept the rationale behind this use of the mask. But a number of English mystery plays would seem to go further. In Chester the annual gilding of ‘God’s’ face that we see in the Smiths’ and twice in the Cordwainers’ accounts is not for Christ in his Divinity, but Christ in his Manhood. The Cordwainers’ play was Simon the Leper and the Entry into Jerusalem, though in the 1550s this was extended into a Passion play involving Annas, Caiaphas, and the Tormentors; the Smiths’ ‘litle God’ is the child Jesus of the Purification and Doctors play.133 Lynette Muir points out that the gilding or masking of Jesus in his Manhood appears to be an English phenomenon, though it is not clear why this should be.134 It is clearly linked to the plays’ incarnational theology and the increasing fifteenth-century impulse to ‘formulate concrete images’ of the theological and spiritual.135 Theatrically, though, it raises complex questions about what happens on stage, and especially about audience reception.

It could be argued that the Chester ‘litle God’ was only gilded for the Midsummer Watch, when he rode out with the two Doctors as part of the Smiths’ show. Some of the record entries might support this: for example, the 1564 entry reads, ‘for Guilding of Gods face’ but the accounts are headed ‘midsomer euen’. In 1568 the entry is included in playing expenses for the whole year, but definitely states that it is ‘for gyldyng Gods face on midsomer euen’, which might suggest that it was not gilded at Whitsun. But the evidence is complicated by the fact that, as Clopper points out, the performance schedule in the 1560s and 1570s was very erratic. Many entries for the gilding of God at Midsummer relate to years when the plays were not performed. In some years, however, the item appears with what are clearly expenses for the play, as in 1571 where it is preceded by ‘for breckfast on Twesday morning 8s’.136 The same applies to the much sparser evidence for the Shoemakers’ Christ of the Passion. In 1561 they paid ‘for the gyldynge of godes fase on medsomar heue iijs’ (three times as expensive as for gilding Little God), but there are no separate play expenses. However, eleven years earlier the item ‘ffor geyldeng of godes ffase & ffor peyntyng of the geylers ffases xijd’ appears among what are definitely play expenses.137 It would certainly suit modern sensibilities more if the gilded God only rode in procession, while a human-faced Christ was left to act in the plays. But the question would remain of how the processional God came to be gilded in the first place; and since the characters in the procession appear to be taken from the plays, the likeliest conclusion is that the play characters were either gilded or masked in gold. It is unfortunate that our fullest records come from late in the sixteenth century when uneasiness may have been developing about ‘a face gilt’.

However, the very terminology of the accounts gives a clue as to the approach to the figure of Christ. He is called ‘God’: the child Jesus is called ‘little God’. So is the Christ of the Coventry Smiths’ Passion play: ‘imprimis to God ijs’. Sharp observes this, remarking of the name ‘God’, ‘or as it is more properly expressed Jesus’.138 Of the nine references to the character in the accounts, only one is to ‘Jesus’, and that in the convenient, almost automatic abbreviation Ihe: the other eight are to ‘God’. The Coventry Cappers’ accounts for their Harrowing and Resurrection play read:

payd to god xxd

paide to the sprytt of god xvjd.139

‘God’ is Christ; ‘the sprytt of God’ is the Anima Christi who harrows Hell while his body lies in the grave. The accounts suggest that it is the divine rather than the human that is perceived as uppermost in the role.

This seems to be borne out in the visual style. The God in the Coventry Smiths’ Passion play wore a garment made of ‘vj skynnys of whitleder’ (1452); this was renewed in 1498, and the entry reads ‘for sowyng of gods kote of leddur and for makyng of the hands to the same kote’.140 The word ‘kote’ suggests something close-fitting, like a body-suit with, apparently, gloves to match. It was worn not as far as we know with a gold mask but a ‘cheverel gyld’ (1490), which seems to have been an alternative way of showing divinity.141 A mid-fifteenth-century inventory from Dundee, although for a procession rather than a play, records ‘cristis cott of lethyr with ye hooiss & glufis cristis hed’.142 Modern audiences tend to assume that the stripping of Christ suggests the pathos and vulnerability of human nakedness: this effect will be much modified and complicated if he is stripped to a ‘kote of leddur’ and a gold wig.143 The script of Chester gives no verbal clue that the Christ of the Passion plays had a gilded face, but in the Towneley Scourging the Secundus Tortor says, ‘I shall spytt in his face, though it be fare-shynyng’, while in the Talents, Primus Tortor says:

PLATE 24: ‘Little God’ (Matthew Lamb) with gilded face, from the Chester Purification and Doctors. Joculatores Lancastrienses, 1983.

© Meg Twycross.

At Caluery when he hanged was

I spuyd and spyt right in his face

When that it shoyn as any glas.144

It would seem that for the medieval playwright and costume-maker Christ must show his Divinity even in the most humiliating moments of his life in the flesh.

To modern audiences such a theatrical language may seem, at least initially, difficult, distancing, or incoherent; but it is clear that it could increase the complex expressiveness of these plays. A major element in the Passion plays is the intensity of Christ’s human suffering, with its undoubtedly moving affective purpose of provoking the audience’s human response. Yet it is not impossible that such a response to vulnerable human distress should be directly combined with a recognition of divine glory. Playwrights may have deliberately emphasised the spiritual implications of what may now seem an unsettling conflict of theatrical signs.

We can examine some of the possible implications through those texts in which the figure of Christ in his Humanity, rather than God the Father, probably wore a golden mask or a gilded face. We have a text for the Chester Smiths’ Purification pageant, which includes the episode of the child Christ with the Doctors in the Temple. We cannot tell if this was the precise form of the play in which ‘litle God’ wore a gilded face, but there is no reason to think it was not similar. Given the subject matter of the play, it would be easy to assume from the script alone that its effect relied heavily on the endearing quality of the child on stage among adults, the little boy who triggers the spectators’ protective feelings and astonishes with his cleverness. But it seems that the gold face, apart from setting the little Christ off from the unmasked characters, reduces this purely affective response. When the child Christ has been gilded in modern production there was certainly far less emphasis on the charm of a ‘little boy among grown-ups’. The gilding obliterated the softness and vulnerability of the child’s skin, and set him apart as unearthly, disconcerting [PLATE 24]. This is supported by the very formal quality of Christ’s speaking part in the text. His words are cool and doctrinal rather than tender and human. He confounds the Doctors by statement rather than by argument: he is what he is, the gold face affirming his authority. Even with his Mother at the end of the play he is detached and formal – the emotion at the reunion is expressed by Joseph and Mary. This is not to say that the impact of the child actor is lost. The child’s voice and presence remain beneath the divine gilding, producing a curiously contradictory effect which makes the audience simultaneously, and rightly, aware of both God and man.

The interaction between the Doctors and the little God is also revealing. Since the Doctors never mention the golden face, it presumably represents divinity to the audience only, not to the other characters. At first the Doctors treat the gold-faced child with a patronising irreverence that suggests that they see nothing special about him at all. But since the audience can see the shining face, their recognition of the incomprehension and misjudgement of the Doctors must be acutely sharpened. Although the Doctors appear oblivious, what the spectators see is the face of God being mistreated. As the play progresses the Doctors become increasingly aware of Christ’s divinity, and as this happens their response to him becomes increasingly reverent. By the end of the play the golden face of Christ seems quite appropriate for the language in which they describe him:

Syr, this child of mycle price

which is yonge and tender of age,

I hould hym sent from the high justice

To wynne agayne our heritage.145

While at the beginning of the play Christ’s golden face and the brisk humanity of the Doctors are working at quite different levels, and indeed at cross purposes, by the end of the play the two have come together into a harmonious expression of Godhead.