The deputy head fearing a revolt made us say prayers in the study rooms and go to bed. At half past nine people threw stones at the dormitory windows after snuffing out the lights: the panes were smashed. The deputy head came and made a speech that only served to excite. When he withdrew, people again broke windows and chamber pots by throwing them against the casements. The deputy head did not know what to do; he went to the garrison and had soldiers placed in the dormitory, with fixed bayonets, to skewer the first person who moved. People did nothing more but they were baying for blood. No one had any sleep all night. I don’t know to what extremes they were ready to go; but I did not join in.

(letter from Jean-François Champollion to his brother

from boarding school in Grenoble, probably summer 1805)

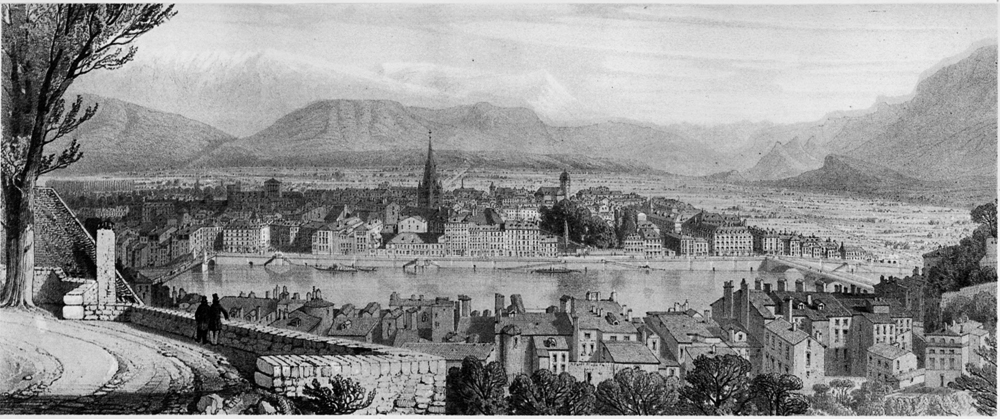

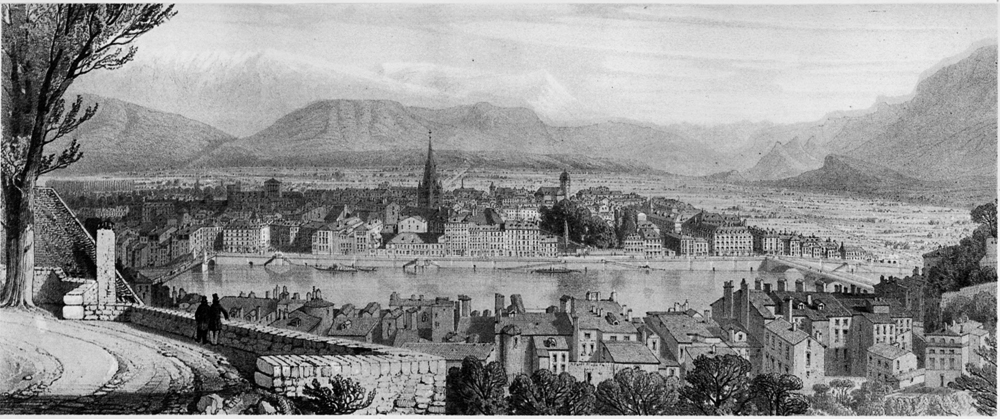

Grenoble, capital of the province of Dauphiné since the 11th century and headquarters of the post-Revolution département of Isère, where Jean-François arrived at the age of 10, would be almost his sole place of residence for the next two decades. For all the many tensions in his relationship with Grenoble, including a period of official exile after the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1815, the city became his home – far more than either Figeac, the place of his birth, or Paris, the city that would make him famous. Writing from the southernmost reaches of Egypt on New Year’s Day 1829 to a close school friend from a Grenoble family, Augustin Thévenet, Champollion claimed that ‘I am always basically a frenzied Dauphinois!’ The phrase represented his gleeful acceptance of the hostile label (‘Dauphinois endiablé’) attached to him by the royalists who had earlier exiled him from Grenoble.

Liberal and republican sentiments were strongly evident in Grenoble’s intellectual and cultural life, although it lacked a university until Napoleon began to establish one in 1805, at which the Champollion brothers would be appointed founding professors. But this republicanism had not led to extremism in its politics. Grenoble had managed to avoid the most violent excesses of the French Revolution, including the Terror, because its nobility had been in the vanguard of reform in 1789. In 1815, Grenoble became the first city in France to welcome back Napoleon from his exile on Elba, with the active support of the Champollion brothers.

Grenoble in the 19th century, where Champollion made his home for two decades from 1801. He always preferred Grenoble to Paris, but his relationship with the city was often tempestuous.

(Bibliothéque Nationale de France, Paris.)

The city’s most famous son in literature, Marie-Henri Beyle – known by his pen name, Stendhal – had a less flattering response to Grenoble than Champollion. Stendhal was born there in 1783 and left his native place for Paris not long before Jean-François’s arrival. In his thinly disguised autobiography, The Life of Henry Brulard (written 1835–36), he writes: ‘All that is base or exhausted in the bourgeois type reminds me of Grenoble, all that reminds me of Grenoble fills me with horror; no, horror is too noble a word – sickness of heart. Grenoble for me is like the memory of dreadful indigestion.’ Yet Stendhal protested too much, even by his own standard, for he could not refrain from showing his respect towards the inhabitants of Dauphiné. He admired what he called the ‘temperament’ of the Dauphinois – a ‘way of feeling for oneself, quick, stubborn, rational … a tenacity, a depth, a spirit, a subtlety’. These were all qualities that Champollion le jeune would in due course display.

Since coming to Grenoble in 1798, elder brother Jacques-Joseph had been lodging in two rooms on the city’s Grande Rue, near his place of employment at Champollion, Rif and Cie, a company that exported goods to the French Antilles, probably with the support of two rich Dauphinois families. But his mind was now increasingly focused on scholarly research rather than commerce. One of his two rooms he had converted into a library, which he continually added to, often purchasing books at very low prices from those whose estates that had been ruined by the Revolution. Thus the 10-year-old Jean-François found himself sleeping in a cocoon of ancient works written in several Oriental languages, which would soon induce him to start upon his life’s research.

Jacques-Joseph had social ambitions too. His decision to change his surname from Champollion to Champollion-Figeac occurred some time after he moved to Grenoble. The longer name served to distinguish him from his Champollion cousins living in the area (and now, of course, from his younger brother); in addition, the adoption of a double-barrelled name was an accepted mark of someone seeking to move up the social scale. Another step on the ladder was his election in December 1803 to the Society of Arts and Sciences of Grenoble, the successor to the celebrated Académie Delphinale that had been suppressed ten years earlier. Champollion-Figeac quickly became active within the society and through it started to work for the influential Joseph Fourier, the mathematician who had recently taken up his appointment as the prefect of Isère after returning from his labours among the savants in Egypt. Four years later, Champollion-Figeac married into an established, if not notably wealthy, local family of lawyers, the Berriats. However, it would be wrong to give the impression that Jacques-Joseph’s worldly networking turned him into a ‘pompous, cunning and venal’ man, even in middle age, notes Jean Lacouture. ‘Nothing of what is known of his relations with the majority of his contemporaries gives credence to such ideas.’ He was both a real gentleman and a committed scholar. Nonetheless, Champollion-Figeac would always be a much more conventional person and thinker than Champollion le jeune.

As soon as Jean-François arrived, in March 1801, he received private tuition from a primary-school teacher – an arrangement made by his brother and always kept under his direction. In addition, Jacques-Joseph taught the boy himself, as he had started to do back in Figeac. After some months, Jacques-Joseph informed their old teacher Dom Calmels about Jean-François’s progress in a letter written in January 1802:

His ordinary work is a translation in the morning, a prose piece in the evening, the rudiments, French grammar; l’Encyclopédie des enfants, and the second book of the Aeneid supply his lessons, to which I add some fables of La Fontaine … I correct his exercises twice a day and as often I ask him to return them and we argue over them word by word … So, Monsieur, these are the means I use to give my brother a little education.

But it was not all bread-and-butter tuition. Six months later, Jacques-Joseph told Calmels: ‘I take care to look for moments of relaxation and then, by all possible means, to resuscitate his taste buds. I give him new food with a subject that is spicy and fresh; sometimes I pilot into port an aptitude floating in the immense space of the imagination. My brother works a lot, he achieves a lot and well.’

In November of that year, Jean-François became a day-boy at a school run by the Abbé Dussert, which had a high reputation in Grenoble. Although it was private, it collaborated with the city’s public education system by sharing some particularly good teachers. One of these was a botanist, Dominique Villars, who took Jean-François on collecting trips into the mountains surrounding Grenoble and treated him as a favourite pupil. The school clearly suited the boy, who received a very good report from Dussert at the end of the first school year, in 1803. Now he was permitted to begin studying not only Hebrew, but also three other Semitic languages: Arabic, Syriac and Chaldean.

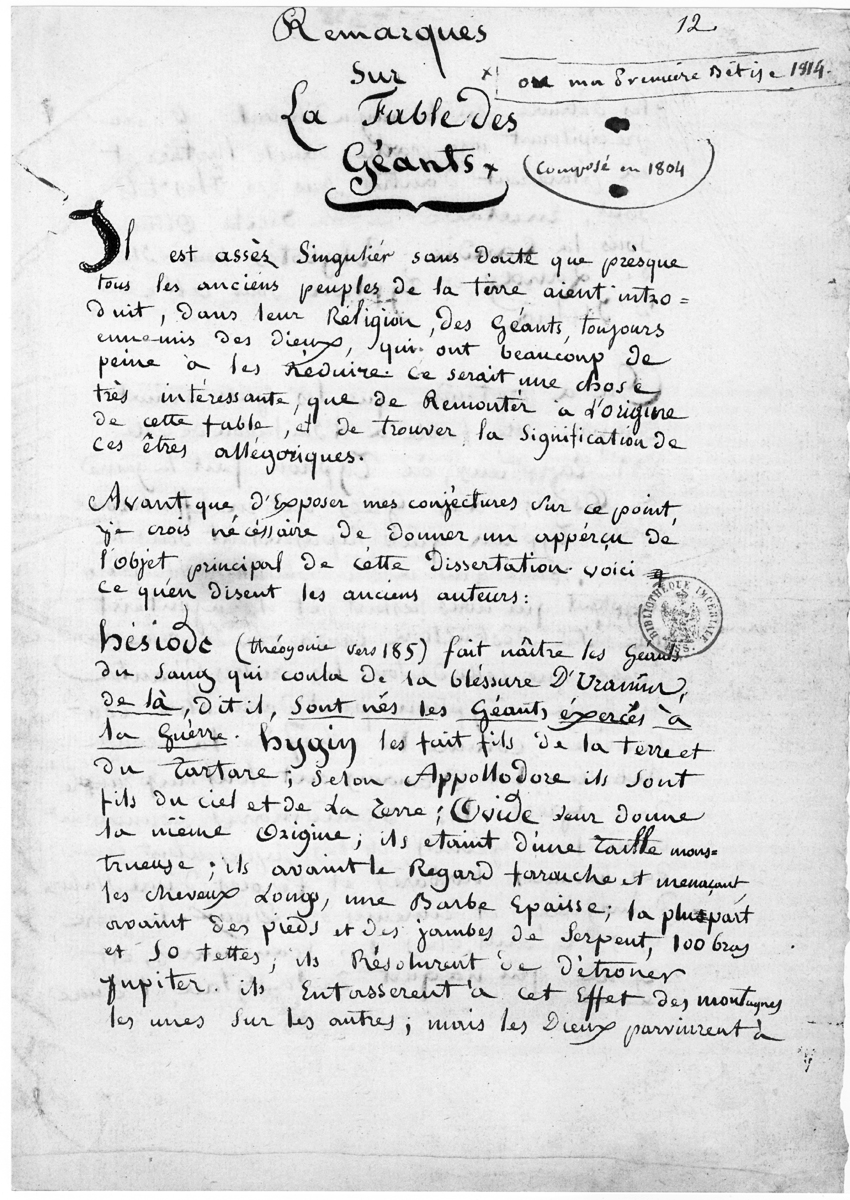

Initially, Jean-François’s desire was probably to imitate his beloved elder brother and to help him in his research for the Society of Arts and Sciences, such as the decipherment of Latin inscriptions found on Roman antiquities recovered from the swamps at Bourgoin in Isère, then being drained under the supervision of Fourier. During 1803, however, he launched himself into his own studies, too – his first passion being the origins of mankind and a ‘chronology from Adam up to Champollion le jeune’. Despite his youth, he was already in touch with leading scholars; the same year the count of Volney sent him his Simplification des langues orientales, followed by his Voyages en Syrie et en Égypte, and in due course a pressing invitation to visit him in Paris. In 1804, aged 13, Jean-François wrote his first published paper, ‘Remarks on the fable of the Giants as taken from Hebrew etymologies’, which was delivered two years later to the Society of Arts and Sciences by General de La Salette, since its author was considered too young to speak on his own behalf. Although within a few years Champollion dismissed the paper as foolish, its theme was an intriguing one: the Oriental origins of European fables about giants. In his own precocious words:

It is without doubt rather singular that almost all of the ancient peoples in the world have introduced into their religion giants, always in rebellion against the gods who have much difficulty in reducing them. It would be a very interesting thing to go back to the origin of this fable and find the meaning of these allegorical beings … It may appear strange perhaps that I search in Oriental languages for the etymology of proper names that appear in Greek myths, but one must not forget that it is from the Orient, and from the Egyptians above all, that the Greeks took most of their fables.

Champollion’s first published paper, written in 1804 when he was 13 years old. At top right, writing in 1814, he calls it ‘ma première bêtise’ (‘my first stupidity’).

(Remarques sur la Fable des Géants, 1804. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.)

From around this time, ancient Egypt began to interest Jean-François more and more – a development that will be discussed in the next chapter, after we have covered his school career.

Dussert’s school was expensive – far too expensive for Jacques-Joseph, whose pocket as a commercial assistant was limited, especially given his burgeoning bibliophilia. Early in 1804, therefore, he asked Jean-François to sit the examination for Grenoble’s government-run lycée; the boy was accepted and given a bursary to cover his boarding fees. Following the summer holidays in 1804, when he returned to Figeac to visit his parents after a gap of more than three years – the last time that Jean-François would see his mother, as it turned out – he reluctantly left his brother’s lodgings and became one of 180 boarders at the new school.

The forty-five lycées spread throughout France had been established by a Napoleonic law of 1802, but the one set up in Grenoble in the building of a former school did not open its doors to pupils until November 1804. The basic syllabus consisted of Latin and Greek literature, and mathematics, with the additional subjects of natural history, chemistry, technical drawing and geography. History, being controversial, was little studied, and philosophy was altogether absent, in deference to Napoleon’s 1802 concordat with the Vatican. Discipline in the school was military: there were uniforms, companies, ranks and drum rolls between events in the timetable, which lasted from reveille at five-thirty in the morning to nine o’clock at night. A draconian prospectus addressed to parents in 1806, apparently intended as reassuring, noted: ‘There is, every day, a period of up to ten hours for work; and a surveillance at all hours, at every minute, at night as well as in the daytime, during recreation time as well as during the period set aside for study, covering even the sleep time of the pupils – does not leave them alone for a single instant.’ Such strictness may have been imposed in response to the dormitory revolt, described at the head of this chapter, that probably occurred in the summer of 1805; the uproar ended only after the arrival of soldiers from the local garrison, carrying fixed bayonets. Although Jean-François claimed to his brother that he was a spectator, not a participant, during the uprising, this seems unconvincing. While it is unlikely that he was a ringleader, surely the injustice of the school’s regime would have induced him, willy-nilly, to show his ‘beak and claws’ along with his fellow pupils.

No wonder, then, that Jean-François – used to living at home with unfettered freedom and to falling asleep while reading his brother’s library books – disliked the lycée and rapidly came to see it as a prison. At one desperate point in his two-and-a-half years as a boarder, he even considered quitting and enrolling at the military school in Fontainebleau. Yet, although he was never happy at the school, he in fact worked hard there during term time, not only on the course work, but also on his private studies. By the time he left in 1807 he was considered an excellent pupil, if hardly a model one. The lycée may not have encouraged Champollion’s particular genius, but it did not try to suppress it.

Indeed, most probably during his first year there, 1804–5, Jean-François played an active role in several school societies concerned with scholarship, very likely with the support of his brother. Signing himself ‘president-treasurer, Champollion’ of the so-called Academy of Muses, he wrote a flowery appeal (undated in its surviving form) to twenty distinguished Grenoblois, inviting them to become corresponding members of the school’s nascent academy. Part of the epistle read as follows: ‘Being too young to judge your work, it is to you that we have recourse … Be for us an Apollo: show us the true path that leads to Parnassus.’ Many of the recipients were probably already aware of who the signatory was, as a result of his brother’s involvement with the Society of Arts and Sciences, and may well have indulged his invitation. Ironically, given this youthful enthusiasm for academic collegiality, Champollion’s later dealings as an adult with a leading French scholarly academy in the humanities, the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres in Paris, would always be ambivalent and at times bitter.

Notwithstanding some stimulating school activities, Jean-François’s health began to suffer, leading him to faint periodically. From this point until his death some thirty years later, he would never be entirely well. The health problems he experienced at the school were partly self-inflicted. Disallowed by the authorities to study privately during the day, he decided to work secretly at night. After lights out in the dormitory, he would lie slightly propped up in bed, with a cotton bonnet on his head, his body angled to the right so as to catch the faint light from an oil-burning streetlamp that fell on his open book; as a result he acquired a slight squint in his left eye as an adult. But presumably most of the deterioration in his health was due to the effects of the school’s spartan regime on a sensitive mind. Extracts from his letters to his brother, quoted by his biographer Hermine Hartleben, make for poignant reading. ‘Send me a little money, because when they let us out it is a real pleasure to be able to drink a bowl of milk, above all when one is really tired.’ Again: ‘I feel that I am not well. I do not know what is hurting my chest, I think I may have an abscess … Besides, the doctor in the infirmary prescribes only herbal tea for coughs to treat all such illnesses, even for toe ache!’ And again: ‘I have a fever, I can’t go on like this. Your obedient brother.’

Some relief came near the end of the first year. The well-known mathematician and physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot – who would later become fascinated by the very same ancient Egyptian astronomical inscription as Champollion – came to hear of Jean-François through his scientific colleague, the prefect Fourier, who was friendly with Champollion-Figeac. Biot met the novice scholar and took pity on his predicament. He asked his friend Antoine Fourcroy, the director-general of public education in Paris, to examine Champollion’s case. During Fourcroy’s inspection of the Grenoble lycée on 1 June 1805, he gave Jean-François a brief examination and then granted him official permission to follow his personal studies during his free hours.

Naturally, this special dispensation irritated some of the school staff, who may have reacted by trying to make the gifted pupil’s life difficult. Things came to a head, probably in June 1806, when Jean-François was 15 years old. We have only his side of the event, as described in an anguished letter to his brother. In this he speaks of a friend in the same division at school (unnamed, but known to have been Johannis Wangehis) ‘whom I have loved with my heart and whom I will always love. He loves me as much as I love him, he helps me to endure the hurts and harshness that people direct at me.’ Now, writes a furious Jean-François, his friend has been deliberately moved to another division by the school authorities. ‘They have counselled him not to spend time with me any more because, they say, I am corrupting him – as if they could not corrupt him better than me’ (the word is underlined in the letter). In Jean-François’s view, the real reason for the move was that the director of studies was a ‘bigot’ and a ‘hypocrite’ who had taken against him, and who also spoke disobligingly of Jacques-Joseph. Any imputation of adolescent homosexual feeling to Jean-François is probably not justified – not least because there are not the slightest hints of such an inclination in his later life, though plenty of examples of male camaraderie. More likely the ‘Wangehis incident’ was an early example of Champollion’s passionate romanticism, his frequent tactlessness (especially towards those in authority) and his lifelong talent for creating enduring enemies at the same time as loyal friends.

A more reliable indicator of the school’s attitude towards Champollion le jeune is that, in August 1806, Champollion was among those chosen to give a speech in front of the prefect, Fourier, when he visited the lycée to assess the quality of public education. Although Jean-François tried to wriggle out of the honour by appealing desperately to his brother for help, his public appearance went ahead, and he acquitted himself well. The Journal administrative de l’Isère reported on 31 August that ‘the young J.-F. Champollion, national pupil’ explained part of the Hebrew text of Genesis in the Bible and answered several questions put to him about Oriental languages; ‘the prefect, who crowned the winners, displayed great satisfaction’. Shortly afterwards, in his report to the government in Paris, Fourier further noted that Champollion le jeune had shown knowledge of beetles, butterflies and minerals, which had been encouraged by his teacher, Villars, who taught him biology at the lycée as he had done at Abbé Dussert’s school.

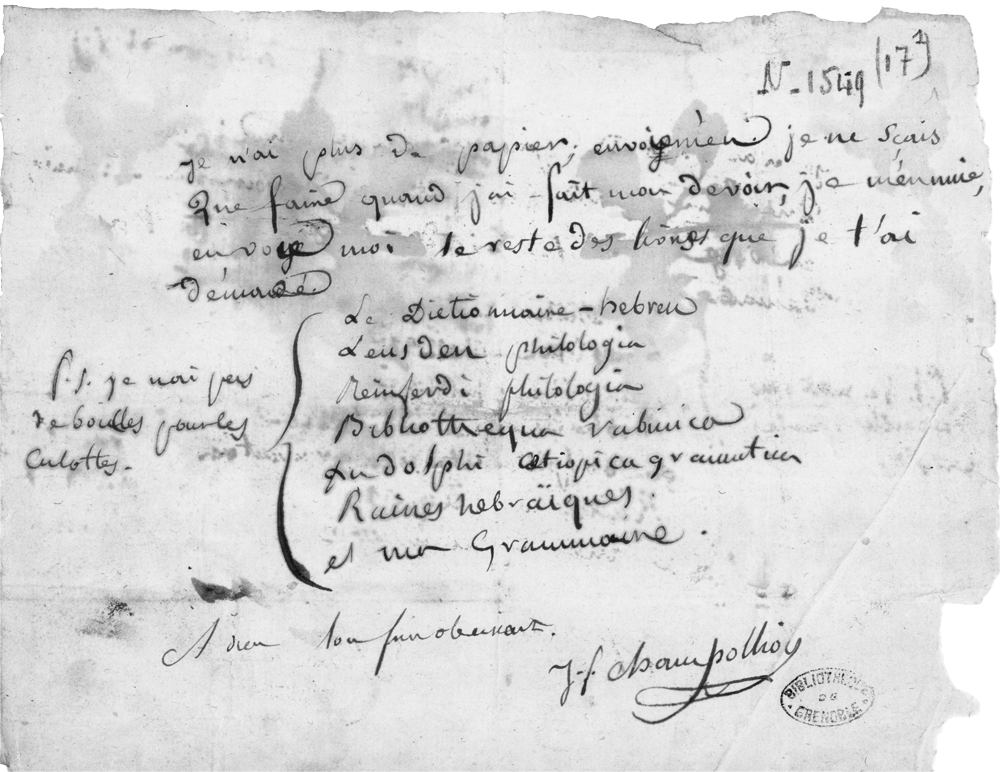

Jean-François’s own linguistic research work, wholly independent of the school syllabus (which included no Oriental languages), was now taking off in earnest. His correspondence with his brother became a stream of demands for books and scholarly assistance. One letter mentions that he lacks buckles for his trousers, and in the very next sentence requests a Latin work on the grammar of the Ethiopic script, the Ludolphi ethiopica grammatica. Another letter asks: ‘I beg you to be so kind as to send me the first volume of the Magasin encyclopédique or that of the proceedings of the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres, because it is not always necessary to read serious things like Condillac’. By the middle of 1806, Champollion-Figeac was no longer able to supply all of the works that his brother needed, and asked advice from a leading Parisian antiquary and naturalist, Aubin-Louis Millin de Grandmaison, the founder of the Magasin encyclopédique. Millin advised that Champollion le jeune come to study in Paris with Silvestre de Sacy or go to the University of Göttingen, which was then admired for its scholarship in languages.

Undated letter from Champollion while at school in Grenoble, requesting from his brother both trouser buckles and scholarly books, including the Ludolphi ethiopica grammatica in Latin.

(Bibliothèque Municipale Grenoble N.1549 (17) Rés.)

After 1 April 1807, Fourier gave Jean-François official permission to move out of the dormitory and return to his brother’s house, so that he might concentrate on his own research while completing only those basic courses required for the lycée’s leaving examinations. In the last of his school reports – which had varied erratically during his two-and-a-half years, between the top grade, A, and almost the lowest grade – Jean-François received five As and three Es, and was even, astonishingly, awarded a prize in his weakest subject, mathematics: ‘what is known as a switchback career!’ comments Lacouture. On his very last day at the lycée, at the end of August, as the usual patriotic speeches were made and the pupils celebrated the beginning of the holidays, Champollion was so overcome at the thought of putting the gates of the school behind him for ever that he fainted into the arms of his friend Thévenet.

A day or two later, on 1 September 1807, barely out of school uniform and a few months short of his seventeenth birthday, Jean-François read his first paper to Grenoble’s Society of Arts and Sciences. Its title was ‘Essay on the geographical description of Egypt before the conquest of Cambyses’. Probably Fourier, prompted by the society’s joint secretary Champollion-Figeac, had proposed this precocious lecture. Even so, the members of the society greeted the adolescent speaker with warmth and genuine respect. On the spot, they moved to elect him a corresponding member, until one of their number, a Dr Gagnon, mildly protested that 16 was too young an age for election (it is noted in the minutes of the meeting). Some months later, now turned 17, Champollion le jeune was formally elected, about four years after his brother. The mayor of Grenoble, Charles Renauldon, uttered some prescient words on the occasion: ‘In naming you one of its members, despite your youth, the Society has counted what you have done; she counts still more on what you are able to do. She likes to believe that you will justify her hopes and that if one day your works make you a name, you will remember that you received from her the earliest encouragement.’