5

The Start

“Ladies and gentlemen!” Charles C. Flanagan cleared his throat and boomed into the microphone. The sound set a flock of pigeons fluttering above the Roman pillars of the Los Angeles Coliseum. He was standing on a wooden dais in the centre of the stand in the home straight. Beneath him, in the bright spring sun, were over two thousand runners circling the track and stretching far out into the stadium car park. The Coliseum, which for the past hour had been entertained by an endless succession of acrobats, clowns, and brass bands, was full to the brim.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Flanagan roared again. “This is indeed an historic moment.” He looked across at the stadium clock. “In ten minutes there will be set in motion the greatest professional long-distance race in the history of mankind, a race in which the cream of the world’s athletes will set out to cross the great continent of America. Each man is a Columbus, for he steps into the unknown, attempting to achieve a conquest that has never before been attempted by any athlete. I wish all of you, each man and woman among you, good fortune. My task is to ensure a fair and honest race. This I will endeavour to do.”

Flanagan half-turned towards the celebrities seated behind him on the dais. “Some of you will already have recognized the distinguished celebrities who have consented to grace this occasion . . .

“Mr Buster Keaton!” All eyes focused on a glum little man on Flanagan’s right.

“Miss Mary Pickford!” There was a ripple of applause as Flanagan moved to his side to reveal America’s darling.

“That great athlete, the fastest man in the world, Charley Paddock!” Paddock, now a plump, moon-faced man, stood up and nodded to the runners.

“The world’s heavyweight boxing champion, Mr Jack Dempsey!” Dempsey, lean and bronzed, stood up and clasped both hands above his head, boxing-style, turning to left and right.

“And finally, a man I am privileged to count as a friend, a man who is both great actor and great athlete, the man who is today going to set you all on your way across America . . . Mr Douglas Fairbanks!”

Waves of applause broke out on all sides. Fairbanks was well-known as a fitness fanatic, an actor who insisted on performing his own stunts. Though the advent of the talkies had caused his star to wane he was still immensely popular: the world’s Mr America.

Looking up, Hugh McPhail thought Fairbanks much smaller than he had expected. Plumper too; Fairbanks was already showing a second chin, and his double-breasted suit strained at its pearl buttons. However, as he stood with both arms out, his teeth flashing in a wide smile, Fairbanks exuded glowing animal fitness.

“My friends,” he said, stilling the applause with raised hands. “When I first heard about Mr Flanagan’s race my first thought was to enter myself.” There was laughter. Fairbanks waited until the stadium was again silent. “Happily, wiser counsels prevailed. Sure, I’m an athlete, I love athletics, but long-distance running was never my strong suit. Jumping, vaulting, capturing pirate ships, rescuing maidens in distress” – he gave a sidelong glance at Mary Pickford – “that’s my bag. Even now I’m just off the set of Around the World in Eighty Minutes. I guess you fellas will take just a little longer to reach New York!” Again there was laughter, and again Fairbanks raised his hands and shook his head. “Seriously, I feel deeply honoured to be here. I suppose in some way this race represents the Great American Dream. Sure, many of you guys and gals have seen hard times. But now, with one throw of the dice, you can change it all, here in the Trans-America.

“As Mr Flanagan has just said, this is the greatest foot-race of all time and it is both my pleasure and my privilege to start the competition.” He lifted from a table a massive double-barrelled shot gun. “So: ladies and gentlemen, get to your marks . . .”

Every muscle in the throng before him was tense, the Coliseum quiet but for the shrill cries of wheeling pacific gulls skimming through its Roman pillars. Fairbanks looked down at the cinder track below him, at the runners coiled in row upon row round the green infield. They reminded him of some still, vital creature waiting to be unleashed.

On the track below, Doc Cole likewise looked around him. Two thousand men and women waiting, poised, to rush across a continent . . . Just behind him were the swarthy Scot, McPhail, the strange limey, Lord Thurleigh, and the lean, impassive Finn, Eskola. A few rows further back stood four of Williams’ All-Americans, dressed in white silk stars-and-stripes vests, and in front of them four crew-cut, sun-blackened young Germans. In the same row crouched the British veteran, Charles Fox, wrinkled and white, eyes almost closed, awaiting the off.

Standing beside him was a slim, attractive young woman, wearing a white vest with the words NEW YORK printed in black front and back. The girl looked poised and confident, and Doc wondered how many other women were sprinkled throughout the field. Whatever the number, he could not see any of them making it as far as Las Vegas, let alone New York.

“Get set . . .” Fairbanks played the moment to the hilt, sensing the tension. His finger tightened on the trigger of the Winchester.

“. . . Go!” The explosion of the gun, the roar of the crowd and the din of the massed infield bands seemed to come as one. Immediately the runners started to move, like lava pouring down a mountainside. Some runners, excited by the dramatic preliminaries, sprinted through the crowds, skidding, stumbling and falling as they bumped into slower, more cautious runners ahead of them. Others simply stood still waiting for space to open up in front of them. Yet others set off in a jaunty, hip-wobbling walk which drew raucous jeers from the crowd. For thirty minutes the mob streamed round the stadium waving and shouting to spectators as they covered two miles of the track before leaving for the open road. Then they moved out into the car park, through the noisy jangle of Flanagan’s carnival, out into the crowded car-lined streets of Los Angeles.

Doc waited till the group ahead of him had departed, then launched into a bandy-legged jog-trot. He looked at his watch. Twenty-nine miles to go: that meant about five hours of running. He wore no socks and his shorts were brief and wide. On his head he wore a sweat band and a peaked white cap. In his right hand he carried a white handkerchief, which he had knotted round his wrist. Hooked to his waist was a small water bottle. It was a long, long way to New York, and it would be a long time before he would give any thought to racing. For the present it was a matter of getting out of L.A., and of running a steady ten-minute miles today and every day. If he could keep doing that he would be around somewhere at the finish.

Ahead and around him Finns, Scots, Americans and English mingled and jostled with Turks, Africans, Chinese and Samoans. Bearded, long-legged Sikhs strode beside tiny, pattering Japanese, slim, brown Californian women beside men from the industrial towns of northern England. On their vests were advertised the wares of Hull, Calcutta, San Francisco, Budapest and Edinburgh. Some ran in modern shorts and vests, others in equipment that had not seen the light of day since the turn of the century. Others ran in tracksuits, walked in ordinary daytime clothes, or even carried sticks. Doc saw at least one blind man and two men without arms.

The variation in speed was remarkable, ranging from fully-dressed walkers striding out at a sedate 4 mph. through to trained athletes running over twice as fast. There was no way that could be kept up, thought Doc; not for sixteen miles, let alone twenty-nine.

He hardly seemed to be moving, pegging along at a steady chugging gait, heel first, his nut-brown bandy legs gobbling up the rutted, dusty road. Yet all around him runners were already falling back, some dropping to a jog-trot, others to a walk. Some, having completed less than five miles, stopped and simply sat by the roadside, sobbing with fatigue, gaping at the stream of runners that poured through the crowded sidewalks east out of the city.

Doc had anticipated neither the dense traffic nor the crowds. For the first ten miles cars were parked two or three deep, and thousands of clapping, cheering spectators lined the route, leaving only a narrow channel for the runners. Ahead, forging a path for them, were Flanagan’s Trans-America bus, the Maxwell House Coffee Pot – a grotesque jug-shaped refreshment van – and a train of press buses.

Hugh McPhail had been sucked in by the early pace, and had gone eight miles through the channel of cheering crowds, also running in the wake of the Coffee Pot, before he realized that he was running much too fast. He dropped back and joined a lean, tanned runner, attired in silk vest and shorts.

“How goes it?” he asked.

There was no reply.

“Suit yourself,” said Hugh, continuing to run at the same even pace, and the two men pressed on in silent tandem. Behind him the four young German runners flowed on like so many smoothly-oiled pieces of machinery. None was much older than twenty-one. All were burnt black with the sun. At their side, on a motor-cycle, cruised their team coach, a bull-necked German with a stopwatch looped on a cord round his neck. “Langsam,” he shouted. “Langsam!” and the young Germans obediently slowed.

Not far behind were the Williams’ All-Americans. Like the Germans, they ran as a team, their fat coach behind them in the back of an open Ford, shouting out instructions on a megaphone. “Relax,” he bellowed, as they made their way up a slight incline. “Stay loose.”

Close on the heels of the All-Americans was little Martinez, clad in close – cut shorts and white vest, flowing along with light, springy strides. He was hardly breathing. Just ahead of him was the Pennsylvanian, Mike Morgan.

At a hundred and fifty-five pounds, Morgan was heavy for a distance-runner. He had a dark, copper-coloured body, with clearly defined musculature. Martinez watched the muscles of Morgan’s back flutter and ripple as he ran, flexing and relaxing on each stride: the Pennsylvanian ran impassively, no sign of effort on his face, its only hint showing in the tiny streams of sweat which ran in rivulets down the muscles of his chest and back. Morgan checked his wrist-watch. Twenty miles to go. No problems.

They were out in the country now, between Montebello and La Puente. The crowds had thinned and the only immediate problem was the exhaust-fumes of the surrounding cars. Doc wiped his handkerchief across his face. All around him men were fading. On the side of the road a man sat whimpering, his bare feet ripped and bloody.

The race had already divided into four identifiable groups. First, there were the trained athletes, men with thousands of miles in their legs, running to their trainers’ orders or to the metronome of past experience, steadily making their way through the twenty-nine miles to Pomona. Behind and amongst them ran fit, hard men who had little experience of competitive racing, men who hoped to flower into athletes in the weeks to come. At the back of the field two other groups emerged. Both were novices, but the members of the first, driven by desperation and strength of will, somehow dragged themselves through the long miles of the first stage. Those in the second group, mind and body shocked even by the efforts of the first five miles, were broken before the field had even pierced the suburbs of Los Angeles.

The Trans-America was thus already spreadeagled along the road east from Los Angeles. From above, in the buzzing Pathé and March of Time newsplanes, the field could be seen, even after only fifteen miles, to stretch over a distance of six miles, snake-like, hardly seeming to move.

For Doc it was an easy run. Twenty-nine miles, no big hills, no real problems. Ten miles from home he cruised past the Germans and the All-Americans, dragging with him Morgan, the broad-shouldered, flat-nosed man he had noted the day before in the hotel. With a mile to go, Doc had passed all but a runner in tartan shorts and his companion, Lord Peter Thurleigh. Together Doc and Morgan pressed on towards the finish of the first stage.

From the brow of the hill they could see laid out on the dry, broken plain the vast tented camp that Flanagan had built for the race: twenty separate dwellings, each capable of holding one hundred runners, and in the centre a giant food marquee. Doc and Morgan trotted down the hill, happy to come in half a minute or so behind the two leaders.

Doc checked his wrist-watch as they passed the finish. “I reckon we made around five hours,” he said, easing down as he approached the rows of notice boards which detailed the accommodation arrangements. Doc and Morgan together scanned the boards and finally located their tent.

“Looks as though we’re bunking down together,” said Doc.

Together they walked through the rows of tents, finally picking out the one allocated them. Beside it, in a separate tent, the washing facilities were primitive. There were only a dozen buckets of cold water and a number of rough blue towels. However, Doc had earlier noticed a river a few hundred yards beyond the camp.

“Looks like there’s a creek nearby,” he said to Morgan, picking up his towel. Morgan nodded, and a moment later had joined Doc on the walk across the rocky plain towards the creek. Once there, Doc sat down on a rock, put his towel round his neck and let the water splash over his feet. He put out his hand to Morgan. “Name’s Alexander Cole,” he said formally, then added: “Most folks call me Doc.”

Morgan responded with a firm grip. “Mike Morgan,” he said, kneeling down and cupping the clear water in his hands and lapping it like a dog.

Their bodies streamed with sweat, and the taste of the water from the stream came as a pleasant shock.

“You run long distances before?” asked Doc.

“Not much.”

“Me, I been running most of my life, one way or t’other,” said Doc. He took hold of one of his feet, rotating it so that the sole was upwards. “Reckon these feet have done one hundred thousand miles.”

They sat in silence, relishing the cool water flowing over their feet and legs. Then they walked back from the creek together, their towels draped over their shoulders. The elder man felt uneasy in Morgan’s company. Morgan was not exactly unfriendly, yet he made no positive response. Doc always felt uncomfortable during silences, feeling obliged to fill them with speech, however inconsequential.

He looked up the hill, now dotted with runners descending on the camp.

“Poor devils,” he said. “First day, last day, for most of ’em.”

As the two men came nearer to the camp centre they were able to view more closely the condition of the latest arrivals. Some, the trained athletes, had experienced no problems and mostly stood drinking and chatting at the Maxwell House Coffee Pot, the sweat steaming from their lean bodies. Others sat on the ground, propped on their hands and knees, gasping, while others lay on all fours, like dying animals, groaning and sobbing. Some were carried off on stretchers by the waiting medical staff. Others simply limped off to their tents.

“Like Bull Run,” said Doc. Indeed, the scene was much like a battleground. Runners continued to trickle from the hill above, but these were no longer competitors, no longer even runners. They either walked, limped or staggered. Some came in by truck or car, to be immediately disqualified.

“One thousand eight hundred and twenty-three,” boomed Flanagan through his megaphone. “One hundred and eighty-nine to come!”

Flanagan’s bellowed instructions continued to fill the evening air. The area beyond the bannered finish was now littered with men and women, the broken remnants of the first thirty miles of C. C. Flanagan’s Trans-America. Doc threaded his way between the sobbing casualties towards the tent marked “Fizz”, the name of the root beer company which had supplied it.

On reaching it he pointed towards a roped-off area fronted by a placard bearing a list of names. He squinted at the list.

“Cole, Morgan – that’s us. McPhail, Martinez, Lord Thurleigh,” he read. He paused, bringing his face closer to the paper. “Jesus, what in God’s name’s a Lord Thurleigh?”

From inside the tent an arm rose languidly from a bed. “Peter Thurleigh. I don’t believe we’ve been formally introduced.”

A man in silk shorts and vest rose and proffered his hand. He was blonde and tanned and had piercing blue eyes.

“Alexander Augustus Cole,” said Doc, introducing himself yet again.

Thurleigh’s grip was weak. He did not shake hands, rather he allowed his hand to be shaken. He ignored Morgan altogether and resumed his seat, laying back with his head pillowed in his hands.

“You spoke last week to the press,” he said. “Aren’t you some sort of doctor?”

Doc nodded sourly. “Some sort of.”

“Good,” drawled Thurleigh. “Might come in handy later.”

The British runner turned over in his bed with his back to Doc, the interview over. Doc shook his head and moved on to his bunk, a rough camp-bed. On the bed next to him lay Martinez, mouth open, snoring. On the other side Hugh McPhail was peeling off his shoes.

“Evening,” said Doc. “Name’s Cole, Alexander Cole.” McPhail looked round, lifting his hand to grasp that of his companion. “Hugh McPhail.” He stood to greet Morgan.

The Pennsylvanian introduced himself, shook hands, and moved over to his bed.

Doc looked around him. “Looks like this is going to be our little family for the next three thousand miles. God willing.”

“What’s God got to do with it?” asked Morgan tersely.

“God sure as hell didn’t intend the human foot to hit the ground six million times in two months,” Doc replied. “Stands to reason we’ll all need His help if we’re going to reach New York.”

There was no reply.

“Time for the trough,” said Doc at last, rising. Morgan and McPhail rose with him, and Martinez, jerking himself to the vertical as if being snapped out of an hypnotic trance, scampered behind. Peter Thurleigh lay still, as though he had not heard.

The tent stank, as the men divested themselves of vests and shorts. It was an exotic aroma, compounded of sweat, faeces, urine and grass, with just a hint of vomit. It was the air they were going to breathe for the next three months.

In the vast refreshment tent about a thousand men and women ate, their utensils clinking noisily on tin plates. They sat on benches, eating from wooden trestle-tables set in long rows.

“Sure ain’t the Ritz, but it’ll serve,” said Doc, sitting down with his food, and flanked by Morgan and McPhail.

True, the fare was not princely. Hamburger and beans, followed by the obligatory apple pie, washed down by hot coffee.

Morgan said nothing, eating his food with almost a cold fury. McPhail gobbled his, hardly pausing between one gulp and the next. Martinez held his face close to his plate, using his fork as a shovel. In the middle of mouthfuls he gulped down his coffee, sloshing both food and liquid into his mouth before swallowing the lot like a seal.

Doc watched his companions without comment. It was clear to him that for them even such a meal was rare. He wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “Looks like that’s dinner,” he said, looking around him. The men finished their meal and walked to the tent exit.

They blinked as they came from the gloom of the tent into the thin evening sun. “Jesus H. Christ,” said Doc, stopping, hands on hips. “I’ll be damned.”

On an open patch of grass stood a black Rolls-Royce. Beside it was a wooden table. On the table stood a gleaming silver salver, plates and cutlery, whilst in an ice bucket stood a bottle of champagne. At the side of the table a butler stood stiffly, impeccable in black evening dress, a white towel across his right arm. On a wooden camp-chair sat Lord Thurleigh, dressed in a dark lounge suit, sipping wine and calmly dissecting what appeared to be roast turkey.

Dixie Williams stood by Flanagan’s massive, gaudy Trans-America caravan and watched the runners come in. She had been watching for almost two hours. Never had she imagined it would be anything like this. Indeed, she had given no thought to the nature of the Trans-America when she had won first prize in a “Miss Trans-America” competition and found that it constituted an “advisory” position in the foot-race. If she had imagined anything at all it was that the Trans-America would be a form of high school dash, with the competitors coming in at the end of each stage breathing heavily, but a few minutes later sipping Coke with the girls at the soda fountain. But never this.

True, some runners came in fresh after the thirty-mile stint, and it surprised her how old many of these men were. They were almost skeletal, the muscles of their thighs standing out like those in drawings from an anatomical chart. She wondered how such sinewy bodies even managed to exude sweat, for they seemed to be entirely composed of muscle and bone. Yet sweat they did, and in profusion, as they stood talking together at the Coffee Pot, drinking endless cartons of iced coffee.

Oddly enough, they did not act like competitors, but more like friends who had simply been out together for a long run on the road. There they stood in the thin evening sun, chatting easily, stripped to the waist, their abdominals rippling like washboards, their bodies still winter-white, while the remaining competitors continued to stream down the hill into Flanaganville.

As her gaze wandered she could see too that the condition of many of the competitors was desperate. Some staggered or walked in, their shirts clotted with sweat, jackets and jerseys draped over their shoulders or round their necks. Some had taken off their shoes and had walked or limped the last miles, their bare feet or stockinged soles now caked with blood. Littered across the vast field competitors lay on their backs, knees bent and chests heaving, or, like animals, propped themselves on knees and hands, coughing and spitting. It was like the remnants of some vast broken army in retreat. Dixie felt tears well in her eyes, and then, turning, was surprised to find the journalist Carl Liebnitz standing beside her. He took off his steel-rimmed glasses, polished them and finally replaced them on his nose.

“I wonder if your boss Charles Flanagan really knows what he’s gotten himself into?” he said. “Some of these poor souls have come straight from the soup kitchens. They won’t make it as far as Barstow, let alone New York.”

Dixie did not know how to respond. “At least they’ll be better fed here,” she said defensively, wiping her eyes with her handkerchief.

“Yes,” said Liebnitz. “Perhaps they will.” He gazed for a moment without speaking, then excused himself and walked off, picking his way between the prostrate bodies of exhausted runners until he had reached the press tent.

Dixie looked across the vast field. On her right were the twenty massive white tents that housed the Trans-America athletes. She walked idly between them and half-glimpsed, in the dim gloom, naked men sponging themselves down from buckets of cold water.

She passed two hysterical, weeping women, supported by attendants, and a moment later saw she had reached the circus caravans. Madame La Zonga, standing outside her caravan, was slowly unwrapping a snake from her neck. She paid no attention to the runners limping in and out of the first-aid tent. She had spent her life in the company of the strange and stricken, and Flanagan’s runners came as no surprise to her. Close by, Fritz, the talking mule, was silently munching grass.

“Hi,” said Dixie.

Fritz looked up, bared his teeth, and returned to his meal. It was evidently not talking time.

Just beyond Fritz’s paddock an elderly man in white tights was juggling with five golden Indian clubs, while behind him two young men trembled delicately in a hand-to-hand balance. To their right a great bull of a man, dressed as a Roman gladiator, grunted as he heaved aloft massive barbells.

A small, middle-aged man – the one who had spoken at Flanagan’s press conference – passed her in the company of a lean, sombre companion. They both had towels over their shoulders, and had obviously come from washing in the river. The elder man nodded cheerfully to her as they passed, but the younger runner gave no sign that he had noticed her.

She watched them both pass. The young man’s body was bronzed and hard and looked as if it had been sculpted: hard defined shoulders, sharp horizontal slivers of muscle across his chest, the flesh of his ribs flickering like tiny fish. Dixie could not understand how a little old man like Doc Cole could possibly challenge such an athlete. And yet she knew from what she had read and heard that Cole was the most experienced runner in the race. She shook her head and made her way back to her caravan.

Carl Liebnitz sat on a camp-chair in the press tent, engulfed in the clatter of typewriters.

“Great day,” said Frank Pollard, tapping out his report on two fingers at the desk beside him.

“Sure,” growled Liebnitz. “Stupendous.” In truth, he did not know quite how to respond to what he had seen.

True, he had seen the Dorando Marathon at the I908 London Olympics and had endured the stupefying boredom of the first dance marathons of the twenties. But the former had been controlled within the limits of a sports stadium and the latter had been a harmless, if sickly, flower of the period. But the human debris now scattered on the edge of the Mojave as a result of Flanagan’s call to arms – that was a human tragedy of a different dimension.

Most of the people littering the ground outside the press tent were not athletes. Liebnitz had seen their like at strikes, soup kitchens and Salvation Army hostels all over the nation. They had no more chance of making it on foot to New York than he had. No, the Trans-America looked to him like just another sad, seamy story of the twenties, to be filed away with pole-sitting, marathon dancing and all the other sports mutations of the period.

“Great day,” he growled again, engaging a fresh sheet of paper on his machine. “Bring on Madame La Zonga and the talking mule.”

AMERICANA DATELINE FLANAGANVILLE 21 MARCH 1931

Charles C. Flanagan’s two thousand-men caravanserai is now making its broken way towards San Bernadino.

A crowded Coliseum, after a couple of hours of carnival high-jinks, saw Douglas Fairbanks, the increasingly portly spring-heeled jack of the silver screen, fire the Winchester that set Flanagan’s hordes surging towards New York. Sadly there were falls, sprained ankles and bruises for many competitors even before the Coliseum exit was reached, as hundreds of Trans-Americans, clearly misjudging the distance between Los Angeles and New York by an odd three thousand miles bolted from the stadium. On and over the bodies of their prostrate comrades they surged; on, ever on, towards their distant goal.

As early as ten miles out, around San Gabriel, the sidewalks were littered with the flotsam of Mr Flanagan’s enterprise. Your correspondent counted at least forty women sitting distraught by the road by the time the press bus had reached Montebello, coughing as they inhaled the exhaust fumes of passing cars. Others staggered on for another six miles or so towards Pomona before collapsing into Mr Flanagan’s following trucks. Close on two hundred failed to complete the first stage to Pomona Hill, just outside Pomona, where a camp, immediately dubbed “Flanaganville” by its weary residents, has been set up.

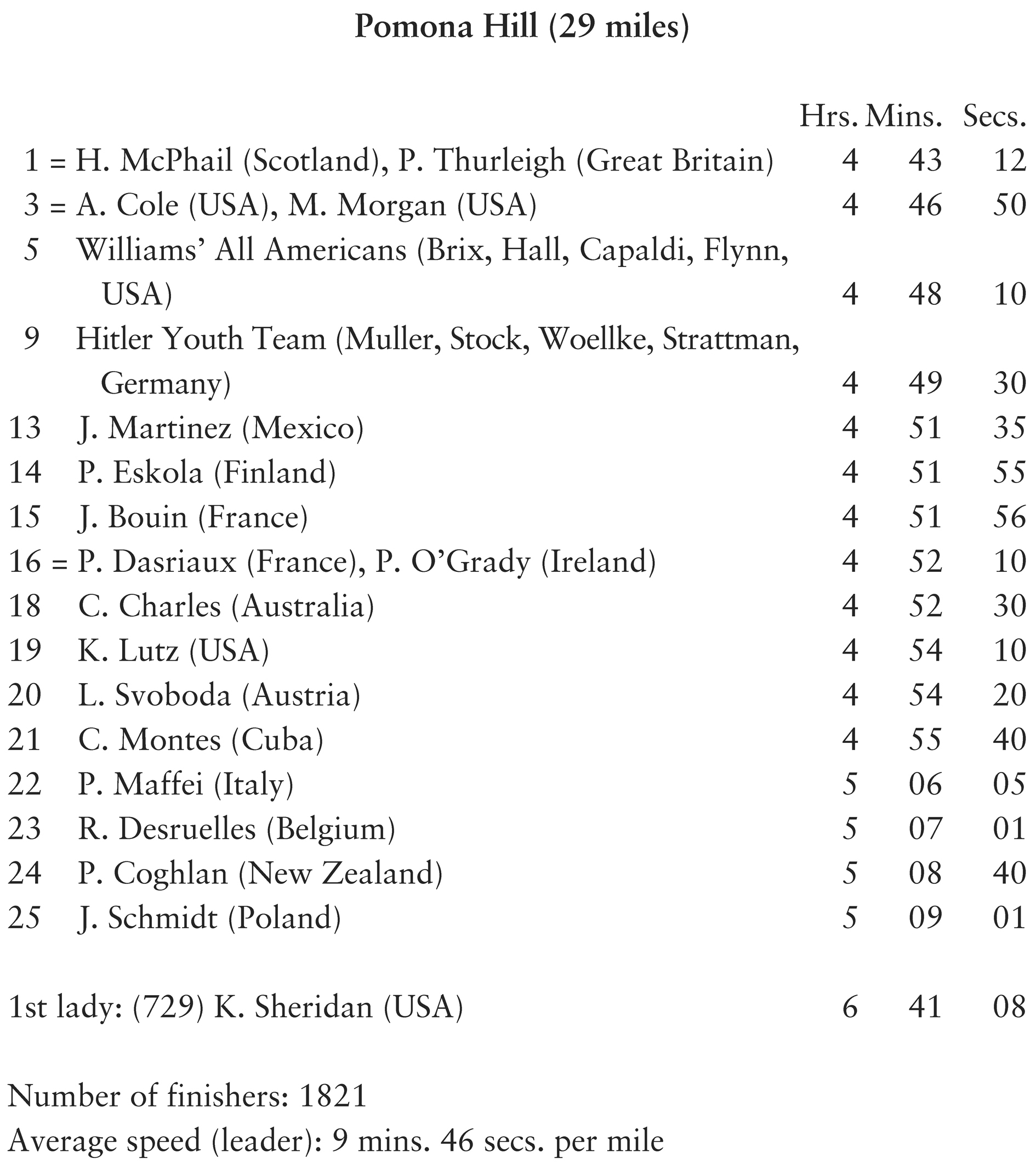

There was little in the way of competition over the first stage. The Scots runner Hugh McPhail trotted in first, with the English aristocrat Lord Thurleigh, followed by Alexander Doc Cole, the fifty-four-year-old former fairground huckster, and the Pennsylvanian Michael Morgan, in that order. Close behind them came the German and All-American teams.

Flanaganville more closely resembles a Gettysburg casualty station than the finish of a foot-race, with its medical tents choked with injured competitors. It remains to be seen if Mr Flanagan’s Trans-America foot-race is a genuine athletics competition or merely another mad little, sad little sports saga of our times. So far, the only person in profit is Mr Flanagan, who is $40,000 the richer from the failure of two hundred-odd competitors to finish the course.

CARL C. LIEBNITZ