1

1517: Theses

Wittenberg

‘Luther, burning with eagerness of piety, issued Propositions concerning Indulgences, which are recorded in the first volume of his works, and these he publicly affixed to the church next to the castle in Wittenberg, on the eve of the Feast of All Saints in the year 1517.’1

It seems, on the face of it, a solid and reliable documentary basis for a defining episode in modern European history. The recorder of the event, moreover, was no merely casual chronicler. The account was written by Luther’s closest ally and collaborator in the emergent Reformation movement. Philip Melanchthon was a Rhinelander, a product of the prestigious universities of Heidelberg and Tübingen, and a brilliant scholar. He was a dozen and more years younger than Martin Luther and proved the almost perfect disciple and foil. Where Luther was rash and abrasively charismatic, Melanchthon was cautious and conciliatory. Luther fired out challenging ideas in sometimes erratic fashion; Melanchthon ordered and arranged them. Melanchthon, rather than Luther himself, has arguably the better claim to be the founder of ‘Lutheranism’, as a distinct and organized religious system. It was he who in 1530 served as principal drafter of the ‘Confession of Augsburg’, a declaration of the core beliefs of the new ‘evangelicals’. It was presented to the Diet, or gathering of the imperial estates, meeting in the city that year. The document became and remained the principal statement of faith of the Lutheran churches in a religiously divided Germany.

Melanchthon was also among the first and most important custodians of Luther’s memory. His account of Luther posting his complaint against indulgences on the (presumably door of the) Castle Church in Wittenberg appeared near the start of a 9,000-word memoir of his friend. It can claim to be the first proper biography of the great reformer. Melanchthon’s Life was composed to serve as the preface to the second volume of Luther’s collected Latin works, issued shortly after the reformer’s death in 1546. Two years later, it was published again in Heidelberg as a free-standing ‘History of the Life and Acts of Luther’. Melanchthon regretted that Luther himself died before being able to write a full version of his own life, though Luther used the preface to the first (1545) volume of his Latin writings to give an account of his actions leading up to and following the composition of the Ninety-five Theses. In addition, fragments of reminiscence and autobiography pepper his sermons and other published works.2 None of these writings, and none of Luther’s thousands of letters, makes any mention of the church door, or the act of posting propositions upon them.

The Ninety-five Theses themselves are one of history’s least likely bestsellers. Luther confessed in 1518—to the pope, no less—that ‘I cannot believe everyone understood them. They are theses, after all, not teachings, not dogmas – phrased rather obscurely and paradoxically’. Yet the work made him a celebrity. In early 1517, Luther was, if not exactly nobody, then certainly not much of a somebody, little known outside of his own order of Augustinian Friars. The author of the Ninety-five Theses was a professor of theology at a not particularly prestigious university, well away from the great European centres of culture and commerce. His only published works were the preface to an incomplete edition of a fourteenth-century mystical tract known as the Theologica Germanica, and a commentary on the Seven Penitential Psalms. A document drawn up in 1515, most likely to drum up recruitment to three, somewhat second-tier, universities in eastern Germany—Leipzig, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, and Wittenberg—listed the noteworthy achievements of 101 professors associated with the institutions. Martin Luther was not even on the list. Yet in 1518, when he wrote to Pope Leo X, Luther was on his way to becoming the most famous priest in Germany.3

Wittenberg in 1517 was a small and unsophisticated, yet prosperous and expanding, community of about two thousand inhabitants, its wealth based on its proximity to regional centres of mining, the industry in which Luther’s father had made his career. The university had been founded only recently, in 1502, at the command of the local ruler, Frederick ‘the Wise’. Frederick was Elector of Saxony, overlord of one of the more significant of the myriad of small states making up the Holy Roman Empire. Covering most of central Europe between eastern France and the modern-day border of Poland, the Empire was a patchwork-quilt of towns and territories, held together only by the fact that most of their inhabitants spoke German, by their common Catholic faith, and by their nominal allegiance to the Emperor, who was chosen by seven Electors—a mixture of secular and ecclesiastical princes.

Luther’s Augustinian monastery was at one end of the main street around which Wittenberg’s buildings clustered. At the other was the Elector’s imposing castle, and its adjacent church, which served as a princely chapel and as a site of burial for the electoral princes of Saxony. It was also the place of worship and main building of assembly for the new university. The church, too, was a recent creation, work on it beginning after an older chapel was pulled down in 1496–7. Construction was only just coming to an end in 1508, when Luther transferred from the Augustinian house at Erfurt to that of Wittenberg, and took up his position at the university.

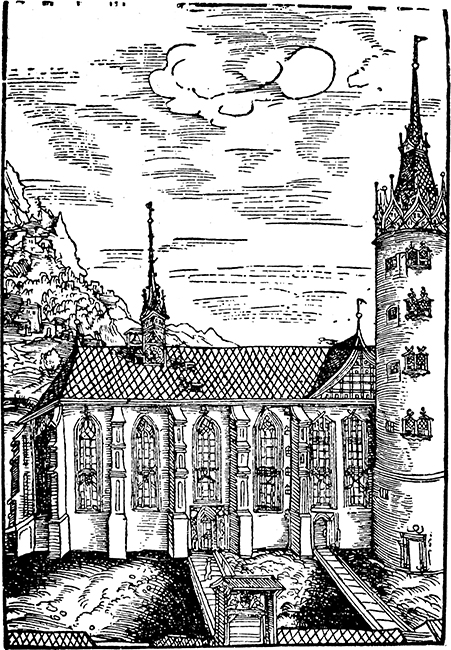

An illustration of 1509 by the Wittenberg court painter Lucas Cranach (see Fig. 1.1) depicts the recently completed church, with wooden walkways across ground still damp and dug-over from the construction work. In the centre, flanked by statues, the artist depicted the main entrance to the church, the portal which, though no one yet knew it, was to become the most famous door in western history.4

Fig. 1.1. The Castle Church in Wittenberg, by Lucas Cranach (1509).

In 1509, the Castle Church of All Saints was famous for something else entirely. Frederick the Wise possessed, and preserved there, an extraordinary quantity of relics. Cranach produced exquisite illustrations of them, along with that of the church’s exterior, for a book cataloguing the collection and promoting pilgrimage to the site. In 1508, there were reckoned to be at least 5,005 relics of saints in the collection, housed in precious reliquaries of gold, silver, and jewelled inlay. By 1520, it had grown to 19,013 items, and included such rarities as a thorn from the crown of Christ, a portion of the milk of the Virgin Mary, and the complete body of one of the Holy Innocents slain by Herod.

Relics were conduits of sacred power. They inspired reflection on the exemplary lives of the holy saints who left bones or other physical attributes behind them on earth. More importantly, the saints in heaven were expected to listen more intently to prayers made in proximity to their remains, and even petition God to perform miracles in response to such prayers. The act of journeying to view relics—pilgrimage—was itself a good work, a source of God’s grace. In Wittenberg, as in numerous other places in medieval Europe, it was also one with explicit prospect of reward. People visiting the Castle Church, and praying before the relics there (as well as those contributing towards the church’s rebuilding work) received the spiritual benefits of specified indulgences.

Frederick was as avid an acquirer of indulgences as he was of relics, an accumulation of pious collectibles going hand-in-hand. Even before its lavish rebuilding at the end of the fifteenth century, Frederick was receiving from the papacy special grants of indulgence to attach to his chapel. Indeed, it was the money pouring into the foundation of All Saints from spiritual tourists visiting the relics and seeking the associated blessings that supplied most of the funds for the establishment of the university in 1502. Luther’s career was one built on indulgences and relics, years before it was to be profoundly and permanently altered by them.5

In 1503, the layers of indulgence enveloping the church of All Saints and its relics were significantly enhanced. The French Cardinal Raymond Peraudi, legate, or authorized deputy, of the pope, visited Wittenberg that year to inaugurate the new church and bestow further blessings on it. Peraudi was a skilled and seasoned preacher of indulgences, or ‘pardons’. He was now on his third tour promoting them in Germany and across northern Europe, with the principal aim of raising money for a papal crusade against the Turks. Peraudi’s visits to German towns were spectacular and well-orchestrated affairs, combining ringing of church bells, ceremonial processions, declarations of amnesty to offenders, open-air masses, and powerful sermons. It all contributed to an atmosphere of heightened devotion which encouraged participants to come forward and receive the proffered indulgences in exchange for the expected donation.

In early sixteenth-century Wittenberg, however, the indulgences were not just one-off opportunities, linked to the visit of a high-profile preacher. They were organically attached to the treasures of the locality. The mere act of visiting the Schlosskirche on the Feast of All Saints, on that of St John the Baptist, or on one of several other specified days, guaranteed one hundred days of ‘remission’. Persons praying in front of the Holy Thorn, or other exhibited relics, and performing additional named acts of devotion, earned further days of indulgence. The amounts obtainable were cumulative. In 1513, anyone with the stamina to perform all of the devotions stipulated by the indulgences attached to Frederick’s relics could in theory earn nearly 42,000 years of remission; by 1518, the achievable target had risen to a precisely calculated 1,909,202 years and 270 days.6

Indulgences

For most people nowadays, this is a head-spinningly alien and even alienating world. What did these figures and aggregations mean; for or from what were people seeking ‘remission’; and what indeed were indulgences, and how were they supposed to work?

There is no doubt that indulgences enjoy a bad reputation in modern society, even—or especially—among modern Christians. They are widely thought to exemplify the corruption and venality of the late medieval Church and papacy, and widespread detestation of them was undoubtedly a principal ‘cause’ of the Reformation. Like most caricatures, this one has some truth to it, but the reality is both more complicated and more interesting.

Indulgences were a part—not the central part, but a far from insignificant one—of a sophisticated system of spiritual exchanges, designed to overcome an inescapable fact about the human condition. That fact was the propensity to sinfulness which, left to itself, made it impossible for human beings to be friends with God, or, after their deaths, to enjoy the right to dwell with Him eternally in heaven: in other words, to be saved.

Salvation is the desired aim, end, and outcome of the Christian life. This was never more obviously so than in the later middle ages, when rates of mortality made death and bereavement a facet of everyday experience, and served to focus everyone’s minds on the life after this one. The principal road-block to salvation was ‘original sin’, a primordial defect intrinsic to humanity, the baleful inheritance of Adam and Eve’s disobedience in the Garden of Eden. God’s decision to become a member of the human race in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, and to ‘atone’ for the collective sins of the world by dying painfully on the Cross, restored the potential for friendship and made salvation possible. But there was still a great deal to do in order for the result to be achieved in the case of any individual Christian.

The process involved a combination of solitary effort and reliance on collective support. The support was offered by the community of believers which Jesus himself established during his time on earth: the Church. It was through the Church, and its life-giving rituals known as sacraments, that God’s favour—his grace—was channelled to people eager to receive it. Such grace was received in marriage, and—the alternative path that Luther chose—in ordination to the priesthood. It was renewed regularly by participation in the eucharist, also known as the mass: a re-enactment of Christ’s Last Supper with his disciples, in which the priest played the part of Jesus, and bread and wine were believed to become, in a fundamentally real way, the body and blood of the Saviour.

Before any of these came the sacrament of baptism, performed as soon as possible after the birth of an infant. Baptism made a person a Christian. In both a symbolic and literal sense, it washed away the stain of original sin. But as experience all too clearly taught, the inclination to sin remained, in both children and the adults they became. The more serious sins were ‘mortal’ ones: unless remedial action was taken, they killed the soul’s prospects of salvation and consigned it to the infernal custody of the devil.

Yet remedy was ever at hand: the flipside of sin was the offer of forgiveness. There was a sacrament for that too: penance. It offered God’s forgiveness of both mortal and less serious (‘venial’) sins in return for feelings of penitence and an honest attempt at a full confession of those sins to a priest, acting here as God’s representative. Theologians argued over whether for the sacrament to take effect people needed to feel genuine sorrow for their sins (‘contrition’) or just a desire to want to feel sorry (‘attrition’)—the second interpretation placed more emphasis on the sacramental power of the priest. But either way, ‘absolution’ wiped the slate clean, and even the most heinous criminal or murderer, if they confessed sorrowfully after the deed, could then die and be assured of a place in heaven.

There was a catch—or rather, as theologians saw it, a perfectly logical and reasonable corollary. God was infinitely merciful: hence the offer of forgiveness for all manner of sins. But he was also infinitely just, and bad behaviour had consequences. Confession and absolution removed the guilt of sins, but not the need to make some kind of restitution for them. God’s justice required penalty, punishment, ‘satisfaction’—just as the modern victim of a serious crime might be willing to forgive the culprit but still expect them to be sentenced and ‘do time’. It was part of the ritual of confession, just before absolution was conferred, for the priest to assign penances. Typically these involved reciting prayers, periods of fasting, or acts of alms-giving; occasionally, undertaking a pilgrimage or some other work of ostentatious devotion. But such penances, and even a lifetime’s tally of worthy deeds and intentions, might scarcely cover the tariff. The typical, averagely good Christian of the later middle ages died with spiritual debts still to pay.

The problem was not insoluble. Centuries earlier, Christian theology had managed to escape from being backed into the corner of teaching that only the extraordinarily virtuous achieved salvation, while the majority were condemned to eternal damnation. The name of that escape-route was purgatory, a third place in the afterlife alongside heaven and hell. Purgatory had somewhat shaky foundations in scripture, and it was a doctrine that emerged and evolved over the course of the early middle ages. But it fulfilled a vital salvific function and served to democratize the afterlife. The unpaid debts, the ‘temporal punishment’ still due for sins, could be paid off there, allowing cleansed souls to proceed in due course to heaven.

It was not an entirely cheerful prospect. Purgatory was a place of punishment, and the consensus of theologians, preachers, and the occasional spiritual visionary was that the penalties endured there by souls were extremely unpleasant. In all likelihood, the experience involved purgation by some kind of spiritual fire, differing from the fire of hell only in its temporary nature. Temporary was a relative term. The nature of ‘time’ in a world beyond this one was understandably perplexing, if not downright impenetrable. Theologians insisted it could be measured only in terms of units of equivalence to periods of earthly penance. But the imaginations of ordinary people latched onto the idea that the likely sentences in purgatory would be handed out in tens, hundreds, thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of years.

This bleak prospect was an incentive to action: there were ways to reduce the length of the purgatorial stay. At the centre of these was one of the Church’s most compelling and attractive ideas. The ancient statement of faith known as the Apostles’ Creed confirmed that all faithful Christians, living and dead, formed a ‘communion of saints’—their fates were linked, and good deeds could be performed by one Christian for the benefit of another. Through prayers, alms-giving, and works of charity, the living could assist the dead and help speed their passage through purgatory. The most powerful work or ‘suffrage’ that could be performed on their behalf was the mass itself, as every mass was a re-enactment in the contemporary world of Christ’s historic sacrifice on Calvary. Across Europe, the dead—or rather, the soon-to-be dead—urged the living to remember them. In their wills, people gave gifts to churches, or to the poor, in return for prayers, and they left funds for sequences of requiem masses to be said for their souls; sometimes for a period of months or years, sometimes ‘for as long as the world shall stand’.7

Here, by a long and circuitous route, indulgences enter the picture. Briefly stated, an indulgence was a certificate granting remission of some or all of the temporal punishment due for sins—they did not ‘forgive’ sins, though, in the way they were spoken about, that crucial distinction was occasionally fudged and blurred. Nor were they ever straightforwardly ‘sold’, though sight of that fact too was sometimes lost.8

Their origins lie in the great, doomed enterprise of medieval western Christianity: the crusades to retake the Holy Places from the occupying forces of Islam. Soldiers of Christ risking death in foreign lands (including Muslim-held Spain) were promised remission of penalties as an incentive to take up the cause. Thereafter, indulgences were offered for undertaking a wide variety of other ‘good works’, and, increasingly, for supporting such good works vicariously by making a monetary contribution towards them.

The question of where this remission ‘came from’ was answered by pointing to the communion of saints. Some members of that communion—holy men and women earning the right to be called Saints with a capital ‘S’, as well as Jesus himself—passed from this world, not in deficit, but with a superabundance of merits. Those surplus tokens of satisfaction remained within the compass of the Church. By the thirteenth century, the view had emerged that they comprised a ‘Treasury of Merit’, whose riches could be drawn upon by the competent authorities. The popes, as heads of the visible Church on earth, were quick to assert that they were custodians of the keys to this treasury—a claim grounded in Christ’s pledge to St Peter and his successors that ‘I will give to you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you shall loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven’ (Matt. 16:19). Only the pope could grant a complete, or ‘plenary’ remission of poena (penalties), removing all the punishment due for sins. Other authorities were delegated to remit lesser amounts; bishops could usually grant forty days of indulgence on their own account.

In light of what was to happen in 1517, it is important to stress that most indulgences were not dispensed outwards from Rome in imperious, high-to-low fashion. As with Elector Frederick’s initiative in Wittenberg, but usually on a much smaller scale, they originated with local communities, with people petitioning Rome to grant an indulgence in support of their particular causes and concerns. The aim might be to add lustre to pilgrimage sites, but was often in aid of the building or rebuilding of churches, or even to assist with what might look to us like ‘community projects’, such as the construction of roads and bridges. It seems likely that people quite often purchased indulgences, not out of a neurotic concern with the condition of their souls, but in order to support such worthwhile causes, much as we might take a sticker from a charity-collector today.

In the main, indulgences were ancillary, not foundational, to the late medieval ‘industry’ of penance and purgatory, whose main focus continued to be on the provision of post-mortem prayers and masses. They were certainly not ever supposed to be some kind of golden ticket, guaranteeing swift entry to heaven with minimal effort or anxiety. To receive the benefits, it was necessary to have been to confession and received absolution, and to remain still in a ‘state of grace’. The grants’ insistence that requisite prayers or good works must be performed ‘devoutly’ was a reminder that indulgences did not work automatically. People making sensible plans for navigating their way through the afterlife rarely relied on indulgences alone.

Still, powerful and genuine longings for spiritual assurance, a desire to assist meritorious causes, and the potential for raising considerable quantities of ready cash, all combined to make indulgences a growth area of late medieval religion. Their scope expanded significantly in the years immediately preceding Luther’s birth. Medieval theologians had long debated the question of whether indulgences could be granted to the already dead. One view was that souls in purgatory were not under the jurisdiction of any bishop, so grants of remission could not be applied to them. Another, put forward by the thirteenth-century Franciscan theologian, Bonaventure, was that indulgences could benefit the dead as well as the living, but in a different way: they were not an act of jurisdiction but an act of intercession on behalf of the dead—albeit a particularly powerful one. However, Bonaventure’s great contemporary, Thomas Aquinas, and other members of the Dominican order, maintained indulgences could be applied to the dead in the same way as to the living.9 Rivalries between religious orders would play a far from insignificant role in the events of 1517.

In 1476, heavily influenced by the arguments of Raymond Peraudi, Pope Sixtus IV issued the bull Salvator Noster. It ruled definitively that indulgences did benefit souls already in purgatory, and could be acquired on their behalf, though they were effectual per modum suffragii—that is, by way of suffrage or intercession. The immediate occasion for the 1476 indulgence was a conventional one—the repair of a church; in this case the cathedral of Saintes in south-west France. But a deal was also being cut with the newly appointed dean of the cathedral, none other than Peraudi himself. Some of the money raised from this plenary indulgence would go towards the perennial papal objective of a crusade against the Turks. The phrasing of the indulgence embedded in the text of Pope Sixtus’s bull is suggestive of the expressive, emotional terms in which indulgences were preached. It was addressed to ‘parents, friends or other faithful Christians’, in the hope that they would be ‘moved by pity for those souls exposed to the fire of purgatory, for expiation of penalties which are theirs according to divine justice’.10

Tetzel

The controversy over indulgences exploding in Germany in 1517 was a reaction to a compound of elements prefigured in the bull of 1476. It involved a declaration of remission to Christians (which could be applied to the accounts of deceased relatives in purgatory) in return for supporting the good work of rebuilding a church, as well as a campaign of selling made possible by a quiet arrangement between Rome and the authorities on the ground.

The circumstances in 1517 were familiar, but also exceptional, for the church in question was the pope’s own: the great Roman basilica of St Peter’s, which Julius II began to rebuild in elegant Renaissance style in 1506. The following year, Julius declared a plenary indulgence in support of the project, and this was reissued by his successor Leo X in 1513 and again in 1515, as the building work progressed.

The second renewal was intimately and fatefully connected to the ecclesiastical affairs of Germany. In 1514, Germany’s most important archbishopric, Mainz—one of three which made its holder an Elector with a voice in choosing a new emperor—fell vacant. Albrecht, the twenty-four-year-old second son of the Elector of Brandenburg was eager to obtain the see. Rome was eager to oblige the high German nobility, but the expense for the young nobleman was steep. In addition to the usual fees associated with the appointment, Albrecht needed a costly dispensation to exercise episcopal office below the minimum age stipulated by canon law. He needed another one to hold Mainz alongside the archbishopric of Magdeburg, which he had also recently acquired: a total eye-watering sum of 24,000 ducats. Without the cash reserves in hand, Albrecht borrowed heavily from the wealthy banking family of Augsburg, the Fuggers.

The indulgence, or so it seemed to Pope Leo, was a win-win solution for all the leading players. Albrecht would permit the papal indulgence to be preached throughout his territories. Half the money would go to the pope and the construction of St Peter’s; with the other half, Albrecht would pay off his loan to the Fuggers. It was, as virtually every commentator since has concluded, a pretty disreputable financial arrangement.11 Luther, like most ordinary priests and lay people at the time, knew nothing about it. His reservations were about aspects of the theology of indulgences itself, and about the ways it was being interpreted and presented by those charged with preaching the indulgence in Germany.

To promote the indulgence, Albrecht turned to the Dominican Order, and in particular to Johan Tetzel, a native Saxon and graduate of the University of Leipzig, with an established reputation as a successful and charismatic indulgence preacher. It was a tough commission. Successive issues of plenary indulgences in Germany, stretching back to the campaigns of Peraudi, meant the market for them was almost saturated. Moreover, Elector Frederick, fearing competition for his own indulgenced relic-collection, forbad the indulgence from being sold in electoral Saxony.

In preparation for the campaign, Albrecht’s court theologians drew up an Instructio Summaria (Summary Instruction) with guidelines to preachers on how to present it most effectively. This confirmed that the new issue superseded and invalidated all previous grants of indulgence for the next eight years—a source of understandable annoyance to people who had bought earlier ones in literal good faith. Generally, the Instructio took a maximalist line on the indulgence’s power and efficacy. Most notoriously, it suggested that people buying the indulgence on behalf of the dead had no need to make confession or exhibit contrition, as its effectiveness depended on ‘the love in which the deceased died, and the contributions of the living’.

This was at best questionable theology, and in preaching the indulgence with the customary pomp and theatricality, Tetzel pushed the boundaries still further. It is likely that he did use some form of the crass and already clichéd slogan that ‘as soon as the coin in the coffer rings, at once the soul to heaven springs.’ He may also have taught, though he later denied saying it, that the indulgence was so powerful it would obtain full remission even for someone who had violated the Mother of God.12 This was, perhaps, technically within the bounds of orthodoxy—if one could imagine such a hypothetical sin being properly confessed and absolved. But it was undoubtedly provocative and distasteful to serious-minded pastors and theologians.

Martin Luther was just such a serious-minded pastor and theologian. Born in Eisleben in Saxony in 1483, he was brought up in nearby Mansfeld, where his father ran a successful mining business. Hans Luder (the form of the name used by the family) wanted his son to become a lawyer, and the young Luther’s decision to enter the Church was an act of rebellion as well as of piety. It was also, he later claimed, the immediate fulfilment of a vow—taken to St Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary, during a ferocious summer thunderstorm: if he survived, he would devote his life to the service of God. In July 1505, abandoning the study of the law, Luther sought admission to the monastery of Augustinian friars in Erfurt, a house of the Observant, or strictly reformed, branch of the order.

Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507, and the following year was summoned by his mentor, Johann von Staupitz, Vicar General of the Observant Augustinians in Germany, to the monastery in Wittenberg and a post in the University, where Staupitz was dean of the theological faculty. Luther was a scrupulously devout young priest, filled, as he later remembered it, with an overpowering sense of his own unworthiness and gnawing doubts about his salvation. At the same time he was building a reputation as a scholar, and succeeded Staupitz as professor of biblical studies in 1512. But, other than in the technical sense, he was not a ‘cloistered’ academic, cut off from contact with ordinary people. In 1514, Luther was appointed preacher at Wittenberg’s city church of St Mary’s; with the position came a powerful sense that souls were entrusted to his care.

As an Augustinian, Luther was also inclined to be suspicious of friars, like Tetzel, from the rival Dominican Order. Luther was on the other side of the argument in 1513–14, when the Dominicans of Cologne tried to bring heresy charges against the scholar Johan Reuchlin because of his interest in Hebrew books. It seemed to many a contest between the forces of old-fashioned, obscurantist, ‘scholastic’ theology, and the new wave of ‘humanist’ learning sweeping through European intellectual life. Humanists believed Christian life could be enriched and renewed by serious engagement with ancient texts, and by returning ad fontes (to the sources)—which of course also meant a greater emphasis on scripture itself. Whether or not Luther was ever really a humanist (this is debated), his lectures from 1513 onwards showed ever greater concern with the Bible in its literal sense.

He was also wrestling with deep questions of faith and repentance, and struggling to understand how Christians achieved ‘righteousness’ or became ‘justified’ in the eyes of God. It would later become crystal clear to him that human effort played no part in this process; that righteousness was ‘imputed’ to, not achieved by, humans on account of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross; that justification came ‘by faith alone’. Some scholars have dated this ‘break-through’ to as early as 1514, though Luther himself later wrote that the pieces only finally fell into place for him in 1519. Others have doubted there was any single moment of conversion and enlightenment. Wherever the truth lies, it is unhelpful to think of Luther at the time of the indulgence controversy as some kind of ‘Protestant-in-waiting’. Early sixteenth-century Catholicism was culturally as well as theologically a broad and often fractious Church. Luther’s emphases on human sinfulness, on the need for humility before God, and on the unforced character of God’s mercy, were characteristic of trends in contemporary piety. Nor was it unusual for preachers, friars in particular, to issue condemnations of institutional corruption and make calls for moral reform. Luther may not have been a ‘typical’ late medieval Catholic, but he was a late medieval Catholic nonetheless.13

Tetzel’s preaching campaign got underway in January 1517. He was banned from preaching in Wittenberg, or entering Saxon territory, but Elector Frederick’s subjects could easily travel to towns just beyond the border—to Eisleben, Halle, Zerbst, and Jütterbog—where Tetzel was plying his trade. In due course, Luther would have seen the certificates they brought back with them, and, as preacher and pastor at the city church of St Mary, he would have heard their confessions and learned to his dismay what they thought indulgences meant.

Even before this, in response to the start of Tetzel’s campaign, Luther was expressing public reservations. In a sermon very likely preached at the Castle Church on the eve or day of the anniversary of its dedication (17 January 1517)—itself, ironically, an occasion for acquiring an indulgence—Luther preached a sermon which, he recalled years later, ‘earned Duke Frederick’s disfavour’. In it, he drew a clear distinction between external penance and ‘the interior and only true penance of the heart’. Luther did not deny that indulgences were useful, or that the pope’s intentions in issuing them were good, but their proper function was simply to remit externally imposed ecclesiastical penalties, and he worried that ‘frequently they work against interior penitence’.

Over the coming months, as reports of Tetzel’s activities multiplied, and a copy of the Mainz Instructio came into his hands, Luther increasingly reflected on what indulgences were and how they should be explained to the people. He included a few swipes against excessive reliance on them in a series of sermons on the Lord’s Prayer, preached during Lent 1517. And, either over the summer or in the autumn, he composed a short tract to clarify his own thinking on the issue.

In this text, Luther elaborated the idea that indulgences, in this life or in purgatory, were solely concerned with remission by the Church of temporal punishments, penalties which the Church itself had imposed. It was indeed ‘most useful to grant and to gain these indulgences’, but principally as a way of clearing the ground for individual spiritual growth. Luther strongly denied that indulgences infused God’s grace into the soul of a recipient, bringing about any increase of charity or any lessening of the inclination to sin (‘concupiscence’). Nor did they provide guarantees of any kind that a soul was ready to enter heaven. Such readiness was the result, not of any plenary indulgence, but of a progression in charity, inner virtue, and detachment from worldly things, whether achieved in the present life or in purgatory. Luther’s main objection to indulgences, as they were currently being preached, was that they encouraged a false sense of certainty and security. What was more, rather than serving as a way to teach people the meaning of salvation, they had become blatantly commercialized, ‘a shocking exercise of greed’.14

Even before he began writing this tract, Luther may have been contemplating the idea of a formal academic disputation on indulgences, to raise awareness of the abuses of the trade and clarify the key theological matters at issue. So it was to that end that he drew up a list of theses or propositions concerning indulgences—not, or not necessarily all, as affirmations of his own fixed beliefs, but as challenging assertions designed to stimulate argument and, so it was hoped, to produce collective enlightenment.

This was a standard way of doing things in late medieval universities. Debates or disputations, which in Wittenberg generally took place on Fridays, supplemented and enlivened the often dull diet of undergraduate lectures. Students defended theses at their promotion to higher degrees, and professors could propose them on topics of their choosing. Luther presided over a controversial disputation in September 1516, at which his student Bartholomäus Bernardi defended theses (heavily based on Luther’s own lectures) attacking the methods of scholastic theology, and the idea that humans could do anything on their own account to deserve God’s favour. On this occasion, Luther suggested to his university colleague Andreas von Karlstadt that he compare the works of scholastic doctors with those of the great father of the Church, St Augustine, whose theology heavily emphasized the unmerited nature of God’s grace. In April 1517, Karlstadt composed a set of strongly Augustinian and anti-scholastic theses which were due to be debated over several days by Saxon theologians chosen by Elector Frederick. This disputation may not in the end have taken place, but Luther sent copies of Karlstadt’s theses to various friends and acquaintances. He also drew up his own set of Ninety-seven Theses against Scholastic Theology, which were debated at the conferral of a degree upon his student Franz Günther on 4 September 1517. These theses were deeply provocative, suggesting that the study of Aristotle—lynchpin of the scholastic curriculum—was actually harmful to Christian theology.15

The number of theses, ninety-seven, was about par for the course in debates initiated by professors, though there were a full 151 on the list drawn up by Karlstadt. On 28 April 1517, Karlstadt wrote to Georg Spalatin, chaplain and chancellor to the Elector Frederick, to say that he had publicly posted them up (‘publice affixi’) two days earlier. It was normal to advertise a forthcoming disputation in this way. Karlstadt did not explicitly say so, though it is perhaps safe to assume, that his theses were posted on the door of the Castle Church.16

Penitence

No manuscript of the Ninety-five Theses, which Luther composed fairly shortly after he compiled the Ninety-seven, survives in the form in which he originally wrote them. The earliest printed versions are prefixed with the announcement of a formal disputation:

Out of love and zeal for bringing the truth to light, what is written below will be debated in Wittenberg with the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and regularly appointed lecturer on these subjects at that place, presiding. Therefore, he requests that those who cannot be present to discuss orally with us will in their absence do so by letter.17

It seems virtually certain that no such disputation ever took place, for there is no record or mention of it. But the Theses were certainly produced in the form of controversial discussion points for a university debate—of the more rambunctious and rhetorical style taking place at Wittenberg over the course of the preceding year.

They began with a categorical and emphatic assertion: ‘Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, in saying “Do penance” [poenitentiam agite], wanted the entire life of the faithful to be one of penitence.’ The second thesis added to this that Christ’s words (in Matthew’s Gospel 4:17) ‘cannot be understood as referring to sacramental penance, that is confession and satisfaction as administered by the clergy’.

To many subsequent readers down the centuries, this has sounded like a clarion call to insurrection, a declaration of theological revolt against the authority of the pope and the sacramental teaching of the Catholic Church. The impression is misleading. In questioning a conventional reading of the Latin Vulgate Bible’s poenitentiam agite, Luther was showing himself to be an acolyte of the great humanist scholar, Desiderius Erasmus, whose edition of the original Greek text of the New Testament, accompanied by his own new Latin translation and explanatory notes, was hot off the press in 1516. It may be significant that it was in a letter forwarding the Theses, written on 31 October 1517, that Hans Luder’s son first gave his name as Martin ‘Luther’. He derived the new spelling from ‘Eleutherius’, a Greek word meaning freed or liberated, the form he used to sign more than two dozen letters over the course of the following year. ‘Classicizing’ one’s identity like this was a humanist affectation: Melanchthon was a literal Greek translation of the solidly Germanic surname Schwartzerdt (‘black earth’).

Erasmus argued that the Greek verb metanoeite (used likewise by John the Baptist in Matt. 3:2) actually meant ‘repent’ or ‘be changed in your heart’—it had nothing to do with ‘the prescribed penalties by which one atones for sins’.18 The change of interpretation was certainly significant, and represented a powerful cry for moral renewal and the reordering of Christian priorities: an authentic inner spirituality over and against the mere externals of worship and conduct. Yet neither Erasmus nor Luther was advocating the abandonment of confession or denying its sacramental character.

The Ninety-five Theses were, without doubt, intended as an excoriating critique of current teaching and practices around indulgences. A number were direct responses to the reported preaching—the ‘daydreams’ (no. 70)—of Tetzel and his fellow commissaries; the ‘human opinions’ of those claiming that ‘as soon as a coin thrown into the money chest clinks, a soul flies out of purgatory’ (27); the ‘insanity’ of teaching a papal indulgence could absolve a person violating the Virgin Mary (75); the ‘blasphemies’ of suggesting St Peter himself could not grant greater graces than those currently on offer (77); or that the cross, emblazoned with the papal crest, and set up in churches where indulgences were preached, ‘is of equal worth to the cross of Christ’ (79).

Such extravagances made it difficult to answer what Luther called ‘the truly sharp questions of the laity’ (81), though whether these were concerns he had actually heard ordinary people uttering is debatable. Why, for example, ‘does the pope not empty purgatory for the sake of the holiest love and the direst need of souls as a matter of the highest justice, given that he redeems countless souls for filthy lucre to build the basilica as a completely trivial matter?’ (82). And again, given his vast wealth, why does the pope not simply construct the Basilica of St Peter ‘with his own money rather than the money of the poor faithful?’ (86). If the pope is seeking the salvation of souls rather than money, ‘why does he now suspend the documents and indulgences previously granted…?’ (89).

These were indeed sharp questions, and Luther articulated them to underline the dire consequences when papal claims about indulgences exceeded their acceptable bounds and undermined efforts to persuade people of the need for genuine repentance. The more theologically substantive of the theses reiterated points made by Luther in his earlier sermons and his indulgence treatise. The pope had no power to remit guilt, and could only lift penalties which he himself or other ecclesiastical authorities had imposed on the living (5–16, 20–1, 33–4, 61, 76). Papal jurisdiction did not extend to purgatory (22). Several of the theses worried away at the connection between remission and contrition, arguing that people were deceived to think that declarations of plenary remission could be effectual for anyone other than the truly contrite, while at the same time noting that, by definition, the truly contrite had no need of them (23–4, 30–1, 35–6, 39–40, 87). Of all the theses, Luther’s prophetic denunciation of abuses was perhaps most neatly summed up in number 32: ‘those who believe that they can be secure in their salvation through indulgence letters will be eternally damned along with their teachers’.

Yet, despite their vehemence of expression, there is little in the Ninety-five Theses to justify seeing in them the manifesto of a new movement, or the declaration of any kind of break with the existing order. While sharply critical of recent papal teaching on indulgences, Luther was in no sense repudiating the authority of Rome, and he was not merely being sarcastic when he complained that one of the problems with unbridled preaching of indulgences was that it ‘makes it difficult even for unlearned men to defend the reverence due the pope from slander’ (81).

Luther’s intention was to limit the scope of indulgences, not abolish them entirely. He conceded (69) that ‘bishops and parish priests are bound to admit commissaries of the apostolic indulgences with all reverence’—a stricture that evidently didn’t apply to Electors of Saxony! Luther did not even deny that indulgences might have some efficacy for those already dead, though the pope’s claim to be able to grant remission to souls in purgatory was ‘not by “the power of the keys”, which he does not possess here, but “by way of intercession”’. This, in fact, was the majoritarian late medieval view of how indulgences could be applied to the situation of the dead; even Sixtus IV’s expansionist bull of 1476, as we have seen, claimed that in purgatory indulgences worked per modum suffragii.

Later Protestants would reject purgatory itself as a fiction and a fraud, an unscriptural accretion to the deposit of Christian faith. Yet at the end of 1517, Luther took the existence of purgatory for granted. More than that, it occupied an important place in his thinking as a site of purification and spiritual growth (15–19).

Another subsequent Protestant (and Lutheran) preoccupation—the denigration of good works—was likewise absent from the Ninety-five Theses. One of Luther’s objections to papal plenary indulgences was that people might ‘mistakenly think they are to be preferred to other good works of love’ (41). Giving to the poor, and similar works of mercy, were certainly ways in which ‘a person is made better’ (44, 42–3, 45–6). Strong emphasis on a sense of assurance of salvation—the bedrock of later Protestant spirituality—is likewise in short supply. In denouncing the false assurance of indulgences, Luther played up the spiritual value of insecurity, stressing that ‘no one is secure in the genuineness of one’s own contrition’ (30). He even speculated that the souls in purgatory might be uncertain of their own eventual salvation (19). This was to go against the considerable (scholastic) authority of St Thomas Aquinas, though other late medieval luminaries, including the great visionary saint, Bridget of Sweden, did believe that certainty of salvation was withheld from them.19 Luther even wondered whether all the holy souls in purgatory would actually want to be fast-tracked out of it (29).

Such abstruse speculations are another reminder that the Ninety-five Theses were propositions for discussion and debate, not a fully worked-out platform or polished dissertation. It is uncertain how fully Luther endorsed all the theses he was putting forward, and one at least—that the pope’s power over purgatory ‘corresponds to the power that any bishop or local priest has in particular in his diocese or parish’ (25)—he surely did not believe to be true. The document contains some aphoristically paired sets of contrary propositions: ‘Let the one who speaks against the truth of the Apostolic indulgences be anathema and cursed’ (71), ‘but let the one who guards against the arbitrary and unbridled words used by declaimers of indulgences be blessed’ (72). And it draws near conclusion with a set of rousing yet paradoxical slogans: ‘away with all those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “Peace, peace”, and there is no peace!’ (92); ‘May it go well for all of those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “Cross, cross”, and there is no cross!’ (93).

The historian David Bagchi has shown that at least fifty-nine of the Ninety-five Theses correspond closely to comments made by Luther in his earlier writings. Martin Luther would indeed develop a revolutionary new theology, but the Ninety-five Theses wasn’t yet it. Critical doubts about indulgences were a fairly widespread phenomenon in late medieval Europe, and many of Luther’s objections stood in both a longer and more recent tradition of concern about abuses of the system. Anxieties that indulgences might work against an understanding of the necessity for true repentance were expressed by such pillars of fifteenth-century orthodoxy as the French theologian Jean Gerson, the Netherlander Dionysius Rickel (known as Dionysius the Carthusian), and the Scot John Major. Tetzel’s 1509 indulgence campaign in the diocese of Strasburg had been roundly condemned by the renowned preacher Johann Geiler von Keysersberg, for paying inadequate attention to the importance of contrition. The recent papal practice of suspending earlier plenary indulgences when a new one was promulgated had already been attacked in a set of grievances presented to the Emperor Maximillian by the German Estates in 1510.20

Humanists generally showed little enthusiasm for indulgences. They were concerned, like Luther (Theses 53–4), that they should not be allowed to usurp the preaching of the Gospel. In his satirical Praise of Folly (1509), Erasmus wondered what there was to say about those who ‘enjoy deluding themselves with imaginary pardons for their sins? They measure the length of their time in purgatory as if by water-clock, counting centuries, years, months, days and hours as though there were a mathematical table to calculate them accurately’. The reference to ‘imaginary pardons’ perhaps allowed Erasmus to claim it was only fake indulgences (of which remarkable numbers circulated in late medieval Europe) that he condemned. Yet elsewhere Erasmus took broad swipes at the folly of pinning hopes of salvation ‘on a piece of parchment instead of on a moral life’.21

Especially after the appearance of his New Testament in 1516, Erasmus’s theological probity was suspect in some quarters; nowhere more so than in the ultra-orthodox Sorbonne, the Theology Faculty of the University of Paris. Yet in a ruling of early 1518, the Paris Faculty denounced as ‘false, scandalous, detrimental to suffrages for the dead’ the proposition that souls fly immediately to heaven the moment the coin drops into the indulgence coffer. In a cautious judgement, at odds with inflated papal claims, the Sorbonne declared, ‘it must be left to God, who decides as he pleases whether the treasury of the Church is applied to the said souls.’ The Paris theologians even sent a circular letter to all the French bishops, to warn them against false preaching as well as the shortcomings of the recent papal bull itself—prompting King Francis I, who had recently signed an agreement with the pope over the governance of the French Church, to step in and close down the debate.

Even some figures close to Rome and the Dominicans expressed reservations about teaching on indulgences. Tommaso de Vio, known from his place of birth (Gaeta) as Cajetan, was an Italian Cardinal, papal diplomat, and Master General of the Dominican Order, no less. In early December 1517, he completed a Tractatus de indulgentiis (treatise on indulgences) for the benefit of Cardinal Giulio de Medici (later to be Pope Clement VII). Cajetan would soon be up to his ears in Luther’s case, but it is unlikely that at this stage he knew anything about the Wittenberg friar or his Ninety-five Theses. Nonetheless, some of Cajetan’s conclusions—expressed in a considerably more measured way—mirrored Luther’s own.

Cajetan was concerned that indulgences were sometimes granted ‘indiscreetly’, without sufficient emphasis on the penitence of the purchaser. He insisted that for souls in purgatory they operated only per modum suffragii, and—exactly like Luther—he took the minimalist view that indulgences could only remit penalties imposed by the Church, not the wider satisfaction required by God’s justice.22 Cajetan did not proceed from this to raise explicit doubts about the Treasury of Merits, as Luther did (56–66), nor to declare that ‘the true treasure of the Church is the most holy gospel of the glory and grace of God’ (62). But one could hardly ask for a more persuasive witness to the fact that, in the early sixteenth century, criticism of indulgences was fairly conventional among thoughtful Catholic theologians. Or that—despite their sharp tone—Luther’s critiques remained within the bounds of what could reasonably be considered orthodoxy.

There was nothing about the Ninety-five Theses that made a schism in the Western Church inevitable, or even likely. How, then, did it happen? In the first instance, that involves examining what actually took place after Luther laid down his pen on the last words of Thesis Ninety-five: ‘the false security of peace’.

Halloween

The date 31 October 1517 is pivotal here—though not because there is any contemporary evidence that on that day Luther marched to the Schlosskirche and defiantly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to its door. Rather, it is because, in a letter dated ‘the Eve of All Saints Day’, Luther wrote respectfully to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz, who was also, as Archbishop of Magdeburg, the most senior churchman of the province in which Wittenberg lay. Luther’s original letter survives in the royal archives in Sweden. There was at least one other letter, which does not survive, which we know that Luther wrote, probably on the same day or just after, to the bishop of Brandenburg, Jerome Schulz, his immediate ecclesiastical superior.

The forms of Luther’s address to Albrecht were appropriate to the disparity of rank between them. He begged forgiveness ‘that I, the dregs of humanity, have the temerity even to dare to conceive of a letter to Your Sublime Highness’. Luther also confessed that he had long put off writing, and did so now ‘motivated completely by the duty of my loyalty, which I know I owe to you, Reverend Father in Christ’.

Still, the letter did not pull many punches. Luther remorselessly itemized the faults of indulgence preachers, misleading the people ‘under your most distinguished name and title’: the coin springing in the box, the insult to the honour of the Mother of God, the erroneous teaching ‘that through these indulgences a person is freed from every penalty and guilt’. Much of the blame lay with the ‘Summary Instruction’, which taught that contrition was unnecessary to purchase remission for souls in purgatory, and that the St Peter’s indulgence would supply ‘that inestimable gift of God by which a human being is reconciled to God and all the penalties of purgatory are blotted out’. Luther was tactful enough to say—and perhaps he really believed—that, though the booklet was published under Albrecht’s name, he was sure this was ‘without the consent or knowledge of your Reverend Father’. He therefore begged the Archbishop to withdraw the Instruction, and to ‘impose upon the preachers of indulgences another form of preaching’.

There was, too, the hint of a threat. If the indulgence preachers were not checked, ‘perhaps someone may arise who by publishing pamphlets may refute those preachers and that booklet—to the greatest disgrace of Your Most Illustrious Highness’. Was Luther thinking of himself for such a role? The eventuality was, he protested, ‘something that I indeed would strongly hate to have happen’, and unless we think we are hearing here the cynical tones of the Mafia-enforcer, we should probably take him at his word.

Along with his letter, Luther supplied Albrecht with a copy of his treatise on indulgences: we know this as Albrecht later forwarded it to the Theology Faculty of the University of Mainz. He also sent the Ninety-five Theses, adding in a postscript—almost, it seems, as an afterthought—that he would be grateful if the Archbishop ‘could examine my disputation theses, so that he may understand how dubious a thing this opinion about indulgences is, an opinion that those preachers disseminate with such complete certainty.’23

The critical point to consider here is whether, at the time he wrote to Albrecht of Mainz, Luther had already announced the public disputation on indulgences; whether, as it were, he came to his writing-desk hotfoot from the door of the Castle Church. The wording of Luther’s postscript gives no clear-cut indication as to whether these were the theses for a disputation already set in motion, or for one envisaged for some future date. As we shall see, there are good reasons for thinking the latter is more likely.

The letter does at least seem to supply a terminal date for the writing of the theses—yet even this is not quite certain. Erwin Iserloh hypothesized that, having composed the letter on 31 October 1517, Luther left it lying on his desk for a few days before sending it off, time he used to draw up in haste his list of theses. This would account for Luther’s reference to his theses appearing in the letter as an appendix, below the inscribed date. It also helps to make sense of a curious later reminiscence, recorded by one of the guests at Luther’s dining table in February 1538. Luther recalled that on the day after All Saints 1517 he travelled to the nearby village of Kemberg, in the company of his university colleague Hieronymus Schurff. It was on this occasion that Luther announced to his friend that he intended ‘to write against the blatant errors on indulgences’. ‘What’, replied Schurff, ‘Do you want to write against the pope?’—adding, presciently, ‘they won’t put up with it’.24

The issue of when precisely the Ninety-five Theses were composed is tied up with the question of the format they were in when Luther sent them to Albrecht of Mainz, either on, or soon after, 31 October 1517. Some scholars suppose that Luther arranged for them to be printed in Wittenberg, and that it was in this form that they were mailed to Albrecht and—supposedly—nailed to the door of the Schlosskirche. If this were so, Luther clearly already intended a wide public circulation of his critiques at the time he wrote to the Archbishop, making his deferential protestations that he was content for the moment to leave matters in Albrecht’s hands seem more than a little disingenuous.

There was a (single) printer in Wittenberg, Johan Rhau-Grunenberg. He operated out of premises in the basement of the Augustinian monastery, and was well known to Luther. We know that disputation theses in this period sometimes were published, and a printed copy survives (discovered in the early 1980s) of Luther’s Ninety-seven Theses against Scholastic Theology, produced by Rhau-Grunenberg. No copy of a Wittenberg printing of the Ninety-five is extant, however, and there is no documentary evidence for its production—though stylistic similarities between the single-sheet broadsheet form in which the Ninety-seven were published, and editions of the Ninety-five printed later in Nuremberg and Basel, have been used to argue that there must have been an original Wittenberg text, on which the others were based.25

Perhaps. Yet the possibility of a printed Wittenberg edition of the Ninety-five Theses does not necessarily equate to such an edition being ready at the end of October, or to its being the form in which Luther sent the Theses to Albrecht, and fairly soon afterwards to other correspondents. It has recently been suggested that ‘it strains credulity that he should have arranged for the Theses to be copied out laboriously by hand so many times to send them to his various friends.’26 But the Theses were a relatively short document, and, despite printing presses having been around in Germany for nearly seventy years, Luther lived in a deeply scribal culture. Literate people (monks especially) were quite used to making multiple handwritten copies of important documents.

Disputation

The next fixed and certain date in any attempt to establish a timeline of events is 11 November 1517. On that day Luther sent a copy of the Ninety-five Theses, his new ‘paradoxa’ as he called them, to an old friend, Johannes Lang, prior of the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt, where Luther himself had once been part of the community. He had previously sent Lang a copy of his Ninety-seven Theses on scholasticism, and it seems to be in reference to these that Luther remarked how ‘all men are saying everywhere about me that I am all too rash and proud in passing judgement’. The impression from the letter is that Luther assumed his new theses would be unknown to his Augustinian brethren in Erfurt—unlikely if they had been posted with any panache in Wittenberg twelve days earlier.

Luther requested that Lang and the theologians of the order would tell him honestly what they thought about his conclusions, and ‘indicate to me the faults of error, if there are any’. But he was not promising the false modesty of waiting to ‘make use of their advice and decision before I will publish’. The verb Luther used here, edere, covers a range of modern English meanings: to publish, publicize, give out, put forth. It seems highly improbable that Luther would use the word here in its future tense if he had already arranged for the Theses to be printed, and seems at the very least unlikely if he had already posted them publicly in Wittenberg.27

Very probably it was now, in mid-November, that Luther began the process referred to in the heading to the printed editions of the Ninety-five Theses, and started to solicit written submissions by letter from ‘those who cannot be present to discuss orally with us’. It would certainly make sense if the Theses were advertised publicly in Wittenberg around the same time.28 So, conceivably, there may have been a Thesenanschlag, on or around 11 November 1517; but if so, no one in the sixteenth century ever made reference to the event.

Luther, it would seem, had waited. He alerted the relevant ecclesiastical authorities to what he saw as a notorious scandal in the preaching of indulgences, and hoped they could be trusted to do something about it. The problem is that he did not wait very long: less than a fortnight after writing to Archbishop Albrecht on 31 October 1517 (assuming the letter was actually posted on that day). Luther certainly wanted and perhaps expected a swift response. Most likely, he sent the treatise and theses to Halle, seat of the Archbishops of Magdeburg, lying little more than a day’s ride to the south-west of Wittenberg.

It was here, at the Moritzburg Castle, rather than in his Rhineland archdiocese of Mainz, that Albrecht chose principally to reside. But in early November 1517, and unbeknownst to Luther, Albrecht was hundreds of miles away, at Aschaffenburg in Bavaria. For whatever reason, Luther’s packet was not opened until 17 November 1517, by diocesan officials in Calbe, halfway between Halle and Magdeburg. They sent it on to the Archbishop in Bavaria. Albrecht had seen the letter by 1 December 1517, when, perfectly sensibly, he forwarded Luther’s materials to the Theology Faculty of the University of Mainz, requesting their opinion. Ten days later, he wrote again, pressing the theologians for an answer, and around the same time Albrecht sent Luther’s letter, treatise, and theses to the pope in Rome. The ruling from Mainz arrived on 17 December 1517. It was brief and fairly non-committal, but judged that Luther had diverged from the teaching of the Church in placing restrictions on the pope’s power to distribute indulgences. The Mainz theologians seemingly assumed that the theses had already, quite properly, been ‘disputed publicly and in scholarly fashion’ at Wittenberg.29

By the standards of large, bureaucratic organizations, it was not a particularly slow or inadequate response. But Luther did not have the cool head of an administrator, and he was itching to start telling the world what he thought. Nonetheless, in his own mind, he had acted entirely properly, even with commendable restraint. Letters by Luther, written over the course of the succeeding year, do not provide an exact timeline of events, but they at least allow us to reconstruct a sequence of causes and justifications in Luther’s own perceptions of the unfolding crisis.

The most important was a letter to the pope himself. Leo X was a cultured scion of the Medici family, who, when he first heard about the indulgence stirs in Germany, was inclined lightly to dismiss them as some ‘quarrel among friars’. Luther wrote to him in May 1518, to defend himself from slanderous reports ‘that I have endeavoured to threaten the authority and power of the keys and of the Supreme Pontiff’. Luther reiterated his complaints about the iniquities of the indulgence preachers, and described how he found himself ‘burning, as I confess, with the zeal of Christ’ to confute them. But he knew it was not his place to take a lead. ‘For that reason I privately warned a few prelates of the Church’. He elicited a mixed response: ‘I was accepted by some and ridiculed by others’. It was only later, when he felt he could do nothing else to check the preachers who were bringing ecclesiastical power into disrepute, that ‘I decided to give at least some little evidence against them; that is, to call their teachings into question and debate. So I published a disputation list and invited only the more learned men to see if perhaps some might wish to debate with me.’ Luther was, he reminded His Holiness, ‘a teacher of theology by your apostolic authority’, someone who possessed ‘the right to hold disputation in public assembly according to the custom of all universities’.30

The impression of an initially very restricted circulation of the Theses is reinforced in a letter of early 1518 to Spalatin, apologizing for not having informed him or the Elector about them sooner: ‘I did not want my theses to fall into the hands of our illustrious prince or anyone from his court before those…who believe they are branded in them, so they do not come to believe that they were published [again, that ambiguous word] by me either by the orders or favour of the prince against the bishop of Magdeburg.’ Luther wrote to Frederick himself later in the year, expressing dismay at reports that he had acted from the start on the Elector’s instructions:

In actual fact, not even any of my intimate friends was aware of this disputation [i.e. disputation document] except the Most Reverend Lord Archbishop of Magdeburg and Lord Jerome, Bishop of Brandenburg…I humbly and reverently warned these men by private letters, before I should publish the disputation, that they should watch over Christ’s sheep against these wolves.31

All this chimes, more or less, with what Luther wrote to Bishop Jerome Schulz of Brandenburg himself, on 13 February 1518. Luther had not at first wanted to get involved in a controversy over indulgences, but found himself persuaded by the arguments of those who condemned the preachers. Still, ‘it seemed the best plan neither to agree nor disagree with either party, but to hold discussion on such an important matter, until the Holy Church might determine what opinion was to be held.’ To this end, ‘I announced a disputation, inviting and requesting all men publicly, but as you know, all the most learned men privately, to make known their opinion in writing.’

No disputation, however, took place: ‘I summoned all into the arena but no one came forward’. The curiousness of this non-happening has not always been sufficiently remarked. If a time and place for a disputation was advertised in the usual way, either on 31 October 1517, or a few weeks later in November, it stretches credulity to believe that literally no one turned up for it.32 Luther may have meant that on the day only his supporters materialized, and so the event was a damp squib, though this is a strained construction on his words, and such an occurrence could surely have readily been portrayed as a triumph. It is noteworthy that the announcement of the disputation prefixed to the (printed) Theses themselves does not specify any date or venue. The possibility cannot be excluded that, touching as they did on issues of politics and authority, as well as theology, the theses were never actually intended for a ‘normal’ academic disputation; rather that, in a more free-floating way, Luther was advocating public debate and discussion, either in person or by written exchange of views.33

Whatever the truth of this, a clear impression from Luther’s letters of 1518 is that at some point he believed he had lost control of the prospects for an orderly ‘disputation’ of his theses. To Pope Leo in May he confessed that ‘it is a mystery to me that fate spread only these my theses beyond the others…so that they spread to almost the whole world’. Around the same time, Luther told the Erfurt professor Jodocus Trutfetter that he was ‘not pleased with their wide dissemination’. On 5 March 1518, Luther informed a friend in Nuremberg, the humanist Christoph Scheurl, that ‘it was not my plan or desire to bring them out among the people, but to exchange views on them with a few men who lived in our neighbourhood’. Luther was in fact apologizing to Scheurl for not having sent him the Theses earlier, in itself an indication of his seriousness about maintaining a tightly restricted circulation. Yet now, ‘far beyond my expectation, they are printed so often and distributed that this production is causing me regrets’.34

In short, rather than remaining within narrow and self-contained scholarly channels, the Theses had got out and caught the public imagination—or at least the imagination of the humanist-leaning, sophisticated town-dwellers who could read Latin. Whatever the complexity or opacity of the theological issues, the impression that an Italian pope was putting one over on honest Germans struck a chord with grievances and prejudices of long standing. Christoph Scheurl arranged for the printing of the Ninety-five Theses in Nuremberg. He was also instrumental in the production of a German translation, though no copy of this vernacular version survives and it may well have remained in manuscript.

Scheurl himself, in an unpublished chronicle compiled a few years later, recalled that at this time Luther’s Theses were ‘frequently copied out and sent here and there throughout Germany as the latest news’. He also reported that Luther allowed his Theses to be printed in response to the opposition they generated—statements which are difficult to reconcile with any printing of the Theses in Wittenberg, prior to any supposed posting on 31 October 1517.35

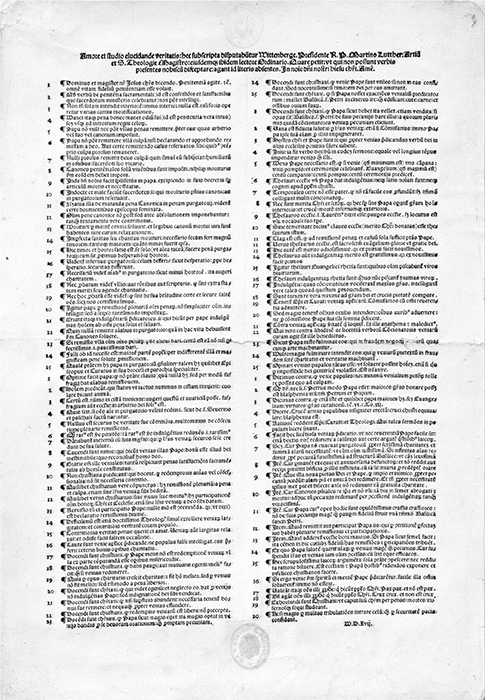

In addition to the Nuremberg printing, two more editions of the Ninety-five Theses were produced, in Leipzig and Basel, and it is possible there may have been others, now lost. Purchasers of these editions may indeed have been confused about the number of theses Luther had written. The Nuremberg broadsheet divided them into four batches, renumbering from the start of each section; the Leipzig printing made a series of errors in numbering, and gave the impression there were eighty-seven (see Fig. 1.2). Only the Basel edition, in booklet form, itemized them consecutively through from 1 to 95. In the cities, the Theses passed from hand to hand, and through networks of humanist communication travelled further afield. In March 1518, Erasmus thought it worthwhile to send a copy of ‘the conclusions on papal pardons’ to his good friend, Thomas More, in faraway England. Years later, Luther recalled with wonderment that his Theses against Tetzel ‘went throughout the whole of Germany in a fortnight’. This may well be so, but, contrary to what is often assumed, that feverish fortnight could not have been in the first half of November: it was probably just before, or more likely just after, Christmas of 1517.36

Fig. 1.2. The Ninety-five Theses: a broadsheet printed at Nuremberg.

Luther’s recognition that his Theses were ‘obscure’ and ‘paradoxical’; that he had not set them out ‘clearly’; that they were being received everywhere ‘not as something for discussion, but as assertions’, impelled him to declare himself with greater clarity. In the early spring of 1518, he began work on a set of Resolutiones, explanations, of the Ninety-five Theses. At the same time Luther composed a short tract in German, a ‘Sermon on Indulgences and Grace’, which aimed to set out in simple and comprehensible terms his understanding of penance and the need for repentance. This work, rather than the Ninety-five Theses themselves, was the real bestseller, going through at least twenty-four separate printings between 1518 and 1520. There was no retreat from the position of extreme scepticism about the value or efficacy of papal pardons. Luther declared his desire to be ‘that no one buy an indulgence’. Yet he did not deny that indulgences numbered among ‘the things that are permitted and allowed’, and cautioned that ‘one should not hinder someone from buying them’. Luther himself doubted whether they could actually rescue souls from purgatory, but some authorities asserted so, ‘and the Church has not yet decided the matter’.37

In 1518, then, Luther was still placing himself firmly within the parameters of acceptable Catholic opinion and debate, and he went to some effort to avoid giving the impression he was deliberately escalating a confrontation. He told Scheurl in March that he had not yet published his Resolutions because he was waiting for formal permission from his superior, Jerome Schulz: ‘my worthy and gracious Lord Bishop of Brandenburg, whose judgment I consulted in this matter, has been very busy and is delaying me a long time’. In the end, episcopal permission was given, and the set of explanations was published in May, with dedications to Johann von Staupitz and to Pope Leo X.38

By conventional reckonings, the Reformation was now already well underway, though no one at the time, including Luther himself, can have cast the matter in those terms. How did Luther, in a relatively short period of time, go from respectful address to the pope, even dedicating important works to him, to completely rejecting the pope’s authority and naming him as the Antichrist, the principle of evil incarnate? It did not happen in 1517, the year the Reformation is supposed to have begun, nor even in 1518, and it was not inevitable that it would happen at all.