2

1517: Responses

Escalation

It was Luther’s opponents who pushed him down a road of radicalization. From the outset they focused on the question of papal authority, with the German Dominicans playing a leading role in fomenting charges against him. In January 1518, at a chapter of the Saxon province of the order in Frankfurt-an-der-Oder—a university disputation which did take place—Tetzel defended 106 Theses attacking the Ninety-five, written for him by the theologian Konrad Koch (Wimpina). In April, Tetzel published a treatise in German attacking as heretical Luther’s ‘Sermon on Indulgences and Grace’, and he defended a further fifty anti-Luther theses at the award of his doctorate the same month. Printed copies of Wimpina’s theses had already in March been shipped to Wittenberg, where a group of students seized the consignment, and committed it to the flames in the market square—this minor outrage, carried out by Luther’s enthusiastic youthful supporters, was the first book-burning of the Reformation era.

Rome, meanwhile, was proceeding cautiously. In February 1518 Pope Leo wrote to the Vicar General of the Augustinians, asking him to silence the German friar who was spreading ‘novelties’ among the people, but the Augustinians were given four months to sort the matter out internally. With attacks on Luther looking like a matter of Dominican vindictiveness, the Augustinian authorities did little to rein him in. Luther attended a general chapter of the German Augustinians at Heidelberg in April 1518, but he used the occasion of a disputation there to defend theses denigrating the power of human free will; what he called a ‘theology of glory’. In its place, Luther advocated a ‘theology of the cross’, of utter dependence on God’s unmerited grace. The claims advanced in these—today largely forgotten—theses were considerably more profound and radical than anything in the Ninety-five.

In the meantime, the pope delegated the task of examining the Ninety-five Theses for possible heresy to another Dominican, Sylvester Mazzolini of Priero (Prierias). The judgement of Prierias, published in June 1518, was unreservedly hostile: ‘whoever says regarding indulgences that the Roman church cannot do what it de facto does, is a heretic.’ Prierias also bluntly asserted that the authority of the popes was greater than that of scripture. It was a response, a modern Catholic authority has conceded, not ‘showing Roman theology at the top of its form’.1

The Emperor Maximilian now forced the pace of the process, writing to Leo in August 1518 to accuse Luther of obstinate heresy. In consequence, Luther was summoned to meet with the papal legate Cardinal Cajetan, at the Diet of Augsburg in early October. Cajetan, though a Dominican, was no partisan inquisitor baying for Luther’s blood. He refrained from directly accusing him of heresy, and his notes on the interviews expressed some sympathy with Luther’s original criticisms of indulgences. But Cajetan detected various errors in Luther’s theology and made abundantly clear to Luther there was nothing for him to do but recant them. Fearing that a safe-conduct arranged by Elector Frederick might be rescinded, Luther secretly left Augsburg—disillusioned, angry, and unrepentant. Before doing so, he arranged for his appeal to Pope Leo against Cajetan’s ruling to be posted to the door of Augsburg Cathedral. In Rome, in November, Leo issued a bull confirming that indulgences drew upon the Treasury of Merits.2

In January 1519, Germany witnessed an event of infinitely greater significance than the stubborn insubordination of a Saxon friar. The death of Maximilian I created a vacancy for the Holy Roman Emperor. The pope was not alone in hoping that Maximilian’s successor would not turn out to be his grandson, Charles of Habsburg, already quite mighty enough as ruler of the Netherlands and King of Spain. In the event, the Electors did choose Charles, his largesse towards them lubricated by huge loans from the Fugger Bank. But for several critical months, the official process against Luther stalled, while both he and his German critics continued to publish and preach.

The most formidable of those critics was a theologian at the University of Ingolstadt, Johann Eck, whose attack on the Ninety-five Theses provoked Karlstadt to compose and publish an impressive 406 theses in their defence. The sequel was a public disputation at Leipzig in June–July 1519, at which Eck rather got the better of both Karlstadt and Luther. After Augsburg, Luther had appealed against the pope to a General Council of the Church—a familiar if provocative gambit in the theological politics of the later middle ages. But at Leipzig, Eck manoeuvred Luther into conceding that General Councils as well as popes could err. The point at issue was the treatment of the fifteenth-century Bohemian reformer, Jan Hus, condemned to death by the Council of Constance in 1415. Luther was pressed into declaring agreement with Hus’s teaching that communion should be given to the laity in two kinds, wine as well as bread. It was a seminal moment: if popes and councils were fallible, then only scripture remained as the source of trustworthy authority for the Christian.3

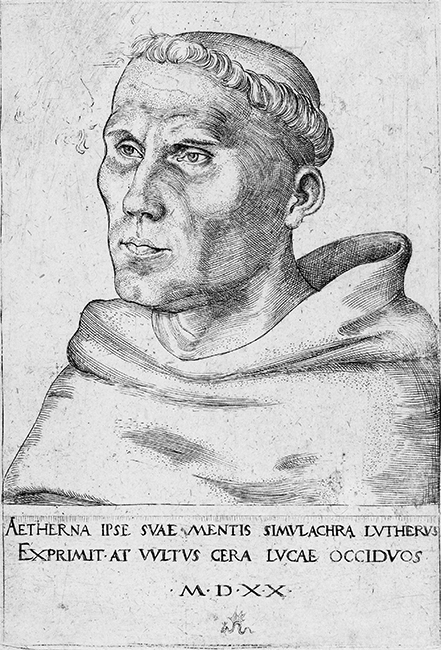

Precarious bridges between Luther and the institutional Church were burned in 1520, for all that in a portrait by Cranach of that year he still looks every inch the traditional Catholic friar (see Fig. 2.1). Luther published three pamphlets which made the critiques of papal authority and traditional doctrine found in the Ninety-five Theses seem mild and inconsequential. One called for the German nobility to step forward and reform the Church, denying there was any difference between priests and laypeople but that of function and office. Another reduced the number of sacraments from seven to three, claiming the others were simply invented by the church of the pope. The third, ‘Concerning Christian Liberty’, disallowed any value to good works and placed unambiguously before the public Luther’s hard-thought-out doctrine of justification by faith alone.

Fig. 2.1. The friar Martin Luther: a 1520 portrait by Lucas Cranach.

While Luther was producing these revolutionary manifestos, Rome had come to its definitive judgement. Pope Leo’s bull of June 1520, Exsurge Domine (‘Arise, O Lord’) promulgated a list of Luther’s errors and threatened him with excommunication if he did not recant. Luther’s response was literally inflammatory. On 20 December 1520, outside Wittenberg’s Elster Gate, Luther threw the bull onto a bonfire, along with copies of the decretals (cumulative body of papal rulings) and the canon law which regulated the life of the medieval Church. A large body of students had been summoned by an announcement of the impending event, which Melanchthon placed on the door of Wittenberg’s parish church. The burning of the instruments of the pope’s authority was a moment of symbolic rupture. Luther wrote shortly afterwards to Staupitz to say that he had undertaken the act ‘at first with trembling and praying; but now I am more pleased with this than with any other action of my life’. He shortly afterwards published a defiant ‘Assertion of All the Articles Condemned by the Last Bull of Antichrist’. Not surprisingly, in January 1521, the pope confirmed Luther’s excommunication.4

The next act in an increasingly intense drama was directed by the new emperor. Charles V was firm in the faith of his fathers, and unsympathetic towards Luther’s calls for a complete overhaul of the Christian life. But he was responsive to the Elector Frederick’s plea that Luther should not be condemned without a hearing, and was willing to offer him a guarantee of safe conduct to attend the imperial diet at Worms. Luther arrived there in April 1521, and was called upon to disown a list of works he had written or edited. In front of the emperor and the assembled notables of Germany, Luther declined to do so. His Latin speech, according to the official record, concluded with a ringing statement:

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of scripture or plain reason (for I believe neither in pope nor councils alone, since it is agreed that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the scriptures I have quoted, and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I neither can nor will revoke anything, for it is neither safe nor honest to act against one’s conscience.

Soon afterwards, accounts printed by Luther’s supporters in Wittenberg, and possibly drawing on his own testimony, added to the speech several further phrases in German: ‘I can do no other, here I stand, God help me. Amen.’ It is possible that Luther never said these famous words, though the contemporary evidence for his doing so is considerably stronger than for his posting of the Theses. Either way, the words he used, and the imposing context in which he said them, were impressive and memorable.5

The consequence was an imperial condemnation, the Edict of Worms, drafted by the papal legate at the diet, Girolamo Aleander. It castigated Luther as ‘a demon in the appearance of a man’, demanded Luther’s capture and deliverance, and declared forfeit the property of anyone supporting him. Yet those supporters, whose numbers were swelling across Germany, included the Elector Frederick, whose agents arranged the ‘kidnapping’ of Luther on his way back from the diet, and his safe bestowal in the Elector’s hill-top castle of the Wartburg. Here, Luther employed his enforced leisure time writing sermons and translating the New Testament into clear and idiomatic German.6

Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1522. After Frederick—despite everything, a deep-dyed conservative in religion—was succeeded by his brother John ‘the Constant’ in 1525, Luther began to oversee the creation of a new territorial Church in Saxony, now decisively separated from the Church in communion with Rome. Other towns and territories followed the same path, and the religious landscape of Germany fractured.

Without planning or intending it, the once obscure Augustinian friar had become the prophet and pattern of profoundly new ways of being Christian. ‘Lutheran’, the derisive label attached to his supporters by Catholic opponents, would in time become a potent badge of pride and identity. Luther continued to write and to preach, and to lead by practical example. His marriage in 1525 to the ex-nun Katharina von Bora was intended to signal that there was no fundamental distinction between layperson and priest, and that the ‘good work’ of celibacy was in no way superior to the raising of a family and enjoyment of sexual relations. For many of his followers, as for Luther himself, his insistence on the Christian’s total dependence on God’s redeeming grace, and that all human actions were intrinsically sinful, was a paradoxically liberating message.

At the same time, Luther strongly upheld the claims of political authority, and condemned in vehement terms the German peasants who rose in rebellion against oppressive landlords in 1524–5, claiming ‘the gospel’ as their justification for doing so. Revolutions in the understanding of salvation, and dramatic restrictions on the social and political power of the clergy, were not to be accompanied by any overturning of the hierarchical order of society. It was on these terms that the new evangelical faith sold itself to numerous German princes, and to the rulers of the Scandinavian kingdoms.

Through to his death in 1546, Luther was read, regarded, and revered. His Bible translation, catechisms, liturgy, and hymns were the meat and marrow of a new corpus of German religious culture. Even so, from an early date Luther ceased to be the ‘leader’ of the anti-papal movement in any practical sense. Other reformers, with theological agendas sometimes diverging dramatically from Luther’s own, took the initiative in shaking off the shackles of Rome, across Germany and beyond. The influential leader of reform in the Swiss city of Zürich, Ulrich Zwingli, later insisted that ‘I began to preach the gospel of Christ in 1516, long before anyone in our region had ever heard of Luther.’ Yet this in itself was an acknowledgement of Luther’s widely recognized place of primacy. He was seen, by both admirers and detractors, as the founding father of something which was not yet routinely called ‘the Reformation’, but which was already regarded as the opening of a new chapter in the story of the Church, and of God’s revelation of himself through history and time.7

Recollections

How, then, did the posting of the Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg come to seem the initiating and defining moment in this ever-evolving process? It is more than a little curious. There were, in Luther’s activity of these years, numerous pronouncements of considerably more theological weight and novelty than the Theses, as well as several episodes of quite evidently greater drama and resonance than their posting: the confrontation with Cajetan in Augsburg, the disputation at Leipzig, the burning of the pope’s bull, the appearance before the emperor at Worms. There is also the further, and far from trifling, consideration that these were all episodes which we know to have really taken place.

As we have seen, there is no strictly contemporary evidence that the Theses were ever posted to the door of the Castle Church. Luther himself, in repeated insistences that he raised the matter privately with the responsible bishops, and only ‘went public’ in consequence of their failure to act, is the strongest witness against the likelihood of any posting on 31 October 1517, the day he wrote to Archbishop Albrecht. It is possible the Theses were fixed to the church door later, in mid- or late November. But if so, Luther never mentioned it: in reams of correspondence, in voluminous theological and pastoral writings, or in the anecdotes and reminiscences recorded by eager students and acolytes.

Some years later, in 1538, a renegade Wittenberg student called Simon Lemnius produced a volume of satirical Latin verses lampooning local dignitaries, which he dedicated, with brazen tactlessness, to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz. Copies of the work were discovered being sold outside the entrance to the Castle Church, provoking a pulpit tirade from Luther against the dishonour brought on the town and university, and against a book-dedication which ‘made a saint of the devil’. But there was no suggestion that a site of particular significance in the campaign against Albrecht and indulgences had been in this way profaned.8 If a Theses-posting at the Castle Church happened at all, it cannot have seemed to Luther an occasion worthy of recollection and notice.

Such an omission was not because Martin Luther lived solely in the moment, uninterested in the twists and turns of his life, or the providential pathways that led him to defy the pope, and become the figurehead for a rediscovery—as he saw it—of the pristine Gospel of Christ. On the contrary, the later Luther spoke and wrote avidly, if sporadically, about the course of his earlier career, and reflected deeply on the significance of his past actions. Luther was intensely concerned with the origins of the movement he had summoned into being, and quite capable of waxing nostalgic about places of personal significance. In 1532, for example, he expressed concern that repair work on Wittenberg’s town defences might end up destroying the study where ‘indeed I stormed the papacy’.9 Luther himself, in fact, was the earliest historian of the Reformation. And in his mind, without any doubt, the date 31 October 1517 was lacquered with profound significance.

The clearest indication of this is a letter Luther wrote on 1 November 1527 to Nicholas von Amsdorf, one of his earliest disciples and oldest friends, by then pastor of the reformed church at Magdeburg. Luther informed Amsdorf that he and another old comrade, Justus Jonas, were drinking a memorial toast together at Wittenberg, ‘on the day of All Saints, in the tenth year after the indulgences had been trampled underfoot’. At that time, the vigil of a major feast was considered part of the day itself, so it is likely that Luther was here thinking of the letters he wrote, and probably despatched, along with the Theses, to the bishops on 31 October 1517. Another possibility, and a perhaps more plausible one, is that the Ninety-five Theses were themselves completed on that day.10

Luther’s later reminiscences could occasionally be fuzzy. In the ‘Table Talk’, the collections of notes taken by guests and students generously and loquaciously entertained in the Luther family home in Wittenberg, a couple of witnesses report Luther as declaring 1516 to be the year ‘I began to write against the papacy’. But in the company of others he correctly identified 1517 as the time ‘I began to write against Tetzel concerning penance’. The pastor Conrad Cordatus, in Wittenberg between jobs in 1531–2, was quite specific in remembering Luther saying that ‘in the year 1517, on the Feast of All Saints, I began for the first time to write against the pope and indulgences’.

Luther’s recollections of this beginning were not without strain and ambivalence. On the one hand, he was in later years painfully aware of the shortcomings of the Ninety-five Theses, almost at times disowning them. In the 1538 preface to a reissued edition, Luther claimed he was only allowing their republication ‘lest the magnitude of the controversy and the success God has given me in it puff me up with pride.’ The Theses, in fact, were a work in which his ‘weakness and ignorance’ was openly on show, for ‘in many important articles I was not only prepared to yield to the pope, but beyond that I even honoured him’.11

This, of course, was no less than the truth. And in the Table Talk Luther is recorded at various times admitting that ‘I did not yet see the great abomination of the pope but only the crass abuses’; that the Theses were originally composed not ‘to attack the pope, but to oppose the blasphemous statements of the noisy declaimers’ (i.e. indulgence preachers). In his fullest fragment of autobiographical writing, the 1545 preface to the first volume of the Wittenberg edition of his Latin writings, Luther begged readers to ‘be mindful of the fact that I was once a monk and a most enthusiastic papist when I began that cause.’ There was a great deal in his earlier writings, including the Theses, ‘which I later and now hold and execrate as the worst blasphemies and abomination’. Luther freely admitted that he had expected the pope to be his protector and supporter when the excesses of the indulgence preachers were first called to his attention.12

Yet it was to the dispute over penance in 1517—more so than to the momentous disputation at Leipzig in 1519, the burning of the papal bull in Wittenberg in 1520, or the defiant stand at Worms in 1521—that Luther assigned foundational significance, even though by his own account he did not come to fully understand and hold the key doctrine of justification by faith alone until sometime in 1519. The indulgence controversy was indeed the moment when Martin Luther ‘began to write against the papacy’.

Nor was Luther entirely apologetic about the style and content of the Theses themselves. He exhorted the clergy assembled at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 to reflect that ‘if our gospel had accomplished nothing else than to redeem consciences from the shameful outrage and idolatry of indulgences, one would still have to acknowledge that it was God’s Word and power’. In 1545, Luther put it more vividly. The Ninety-five Theses, his subsequent explanation of them, and the vernacular sermon on indulgences: all these were works ‘demolishing heaven and consuming the earth with fire’—or so it seemed to his opponents.13

Luther himself then was the chief originator of the tradition that the Reformation ‘began’ in 1517, and that it should moreover be linked to a precise date: the Vigil and Feast of All Saints. This, let us note, was an interpretation and a retrospective autobiographical claim, not a simple historical ‘fact’. But from an early date it was a perception widely shared in the circles of Luther’s supporters. It is true there is no mention of the Ninety-five Theses in the surviving version of the ‘Annals of the Reformation’, compiled before his death in 1545 by Luther’s close ally, Georg Spalatin. The account begins with Luther’s summons to face Cajetan’s heresy charges at the imperial diet at Augsburg in 1518—a scene never quite fulfilling its potential for iconic status. But this was likely due to the fact that, as the manuscript’s early eighteenth-century editor remarked, ‘through the long passage of time both beginning and ending have been completely lost’. Other chroniclers of the first generation did emphasize the significance of the indulgence controversy, even if some, like Nicholas von Amsdorf and Johan Aurifaber, conceded that Luther still displayed ‘papistic’ tendencies when he composed the Theses, and had further to go in understanding the gospel.14

The idea that the year 1517 was a crucial turning-point in the history of Christianity, a moment of prophetic witness, and the making of a new start, became at an early date something of an article of faith among Luther’s disciples and supporters. Johann Agricola was a Wittenberg scholar who was at Luther’s side during the Leipzig Disputation of 1519, and for the burning of the pope’s bull the following year. He wrote, in a biblical commentary of 1530, that true doctrine, persecuted and blasphemed against by popes, was ‘in the year of Our Lord 1517, by the grace of God, at first reborn, by the advocacy of Martin Luther’.

This perception was encouraged by the growing popularity of printed almanacs and chronologies. Johan Carion, court astrologer to the Elector of Brandenburg, compiled an ambitious chronicle of world history, published at Wittenberg in 1532. Carion was an old school-friend of Melanchthon, who took a close interest in the progress of the work. It proved immensely popular in Lutheran Germany, going through fifteen editions by 1564. Carion’s final entry for the reign of the Emperor Maximilian I was a terse but emphatic note that in 1517 ‘Martin Luther first wrote against indulgences, after which many disputes arose. And out of that a great divide has grown in Germany.’15

A more detailed and florid account of the origins of that great divide appeared in the Historia Reformationis of Friedrich Myconius, an early supporter of Luther and pastor in the city of Gotha, a work composed in 1541–2, though remaining in manuscript until the early eighteenth century. Like all other commentators before the mid-1540s, Myconius knew nothing of any theses-posting on the door of the Castle Church. But he had a strong sense for the dramatic setting, and saw in Martin Luther a man who was literally heaven-sent. Myconius asked his readers to visualize the humble chapel where Luther preached in the precincts of the monastery in Wittenberg: it looked ‘just the way painters portray the stall in Bethlehem, where Christ was born.’ It was in this poor, wretched place that in these late days God had allowed ‘his dear holy gospel, and the dear child Jesus, to be born anew’.

After some preambles on the corruptions of the papacy, Myconius began his story properly in 1517, with the indulgence controversy. His account largely followed that of Luther himself, though Myconius added the intriguing detail that, before drawing up the Ninety-five Theses, Luther wrote with his concerns about indulgence preaching to four bishops—of Frankfurt, Meissen, Mersburg, and Zeitz—as well as to the Archbishop of Mainz. It was only when he saw the bishops didn’t want to do anything about it that Luther composed the Theses, and allowed them to be printed, though his intention at this stage was only for a debate about indulgences among ‘the learned of Wittenberg’. To Luther’s own recollection that, within two weeks, the Theses had gone through all of Germany, Myconius added an arresting sequel: within four weeks they had spread across the whole of Christendom, ‘as if the angels themselves were the message-runners’.16

There was no suggestion of angelic assistance in another account of the Reformation and its origins composed at around the same time. This was a biography of Luther which began by reporting how many people believed ‘he enjoyed an occult familiarity with some demon’. The author was Johannes Cochlaeus, canon of Breslau Cathedral, and sometime chaplain at the court of Duke George of Saxony, cousin and rival to the Elector Frederick. Cochlaeus was an educated man, a humanist, and personally acquainted with Luther. But from an early stage he revealed himself as one of the reformer’s most relentless and effective denigrators. By the time his Commentaria de actis et scriptis Martini Lutheri (Commentary on the deeds and writings of Martin Luther) was published in 1549, Cochlaeus was already an old hand at anti-Luther polemic. His biography of Luther was a work of considerable research and erudition, as well as copious quantities of vitriol. It was written primarily to disabuse deluded fellow-Germans: ‘the majority of people living today think, by the crudest of errors, that Luther was a good man and his gospel was a holy one’.17

As a humanist attuned to the importance of verifiable sources, Cochlaeus quoted in detail from the letter Luther wrote to Archbishop Albrecht, ‘from Wittenberg, on the Eve of All Saints, in the year of our Lord 1517’. But Luther was not genuinely moved by concerns about abuses in the preaching of indulgences; instead, he was motivated by ‘envy’ and the arrogant desire to display his intellect which was already characteristic of his career as a monk. The indulgence controversy was simply an occasion, rather than the cause, for a long-brewing rebellion against the Church. Like other Catholic critics of Luther in the first half of the sixteenth century drawing attention to the attack on indulgences—Johann Eck, Kilian Leib, Hieronymus Emser—Cochlaeus did not mention any posting of the Ninety-five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg as the symbolic form this rebellion took. Nonetheless, Luther, in Cochlaeus’s telling of events, was not content to send his letters privately to the Archbishop, ‘but also he publicly announced ninety-five theses’. Cochlaeus added—perhaps to make Luther seem still more unstable and inconsistent—that ‘in the first draft he had written ninety-seven’.18

Melanchthon

Melanchthon’s 1546 short Life of Luther was composed around the same time as Cochlaeus’s much longer biography. It might have been describing an entirely different man. Melanchthon laid equal emphasis on the events of 1517, but placed an entirely contrasting construction on their meaning. Before that date, Luther was a faithful and conscientious monk, though one positively influenced by the classical studies of Erasmus, and already teaching a sincere doctrine of faith and penitence ‘not found in Thomas, Scotus, and others like them’ (the scholastic theologians Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus). It was the ‘shameless’, ‘impious’, and ‘execrable’ teachings of Tetzel, bursting onto the scene in 1517, that virtually forced him into taking a public stand. Luther, in this sequence of events, was the pure and proximate instrument of God, in no respect driven by his own desires or ambitions. It was thus no ostentatious or vainglorious act on Luther’s part, when, having written ninety-five theses against the delinquencies of Tetzel, he ‘publicly attached these to the church attached to Wittenberg Castle, on the day before the feast of All Saints, 1517.’19

Any competent historian needs to pause, and take a very deep breath, before dismissing outright this testimony for the authenticity of what came to be seen as the seminal public event of Luther’s career as a reformer—even despite its relatively late arrival on the documentary scene. Melanchthon could not have witnessed any such posting in 1517, but he arrived in Wittenberg in August of the following year and began a close collaboration with Martin Luther that would last for almost three decades. The simplest explanation is surely that Luther informed Melanchthon he had undertaken this action on 31 October 1517, and that Melanchthon remembered the incident and included it in his biography.

Luther’s younger friend was, moreover, no slapdash or deceitful chronicler of events. At the beginning of his biography he put on record how he had ‘several times’ asked Luther’s mother Margarita about the date and circumstances of her son’s birth.20 It is unlikely that Melanchthon deliberately fabricated a story about the posting of the Theses which he knew to be untrue. Melanchthon almost certainly believed, or had come to believe, that such an episode took place. It is worth noting that there is no record of anybody who was in Wittenberg in 1517, and still alive in 1546, coming forward to contradict Melanchthon’s memory of events—though it is a little hard to imagine what form such a public contradiction of Wittenberg’s leading reformer might have taken.

What is certain is that if Luther himself did not consider the episode worthy of public report, neither, prior to 1546, did Philip Melanchthon. In a letter of 1519, Melanchthon made reference to Luther proposing a disputation about indulgences, but said nothing about church doors. A couple of years later, in a work defending Luther against the Italian Dominican Thomas Rhadinus of Piacenza, he spoke simply of how Luther ‘modestly’, and ‘acting like a good shepherd’, proposed difficult questions (paradoxa) about indulgences, ‘according to the custom of scholars’.21

But what actually was ‘the custom of scholars’? The mystery of the Thesenanschlag is perhaps resolved, perhaps deepened, by a separate and independent note concerning the posting of the Theses, one which in all likelihood predates Melanchthon’s by a couple of years. Its author was Georg Rörer, a close collaborator of Luther, and the editor of several of Luther’s works. Rörer first arrived in Wittenberg in 1522, and so, like Melanchthon, could not have been an eyewitness of any posting in 1517. Yet he had both a personal and professional interest in Luther’s journey of faith and witness. Rörer was particularly involved, as proofreader and copyist, in the efforts leading to the publication in 1546 of a revised version of Luther’s German translation of the Bible.

It was most likely in the course of this editorial work, coming to an end in 1544, that Rörer inscribed a sentence in Latin into a 1540 copy of the New Testament, used by the editors as a base-text for revisions. In 1972, the note was printed, in a supplement to Volume 48 of the vast Weimar Edition of Luther’s works, but, remarkably, for thirty-four years no one really noticed. Then, in 2006, Martin Treu, exhibitions director of the Luther Memorials Foundation in Saxony-Anhalt, rediscovered the inscription in the original Bible in the University and State Library in Jena. It reads: ‘On the eve of the Feast of All Saints, in the year of Our Lord 1517, theses about indulgences were posted on the doors of the Wittenberg churches by Dr Martin Luther.’22

It looks like a decisive endorsement of Melanchthon’s account, confirmation of both the fact and the traditional dating of the Thesenanschlag. Yet one discrepancy immediately jumps out. Rörer has the Theses appearing on the doors—plural—of the Wittenberg churches, which must at least mean they were posted on the door of the parish church of St Mary’s, as well as on that of the Castle Church. Is it likely, then, that there was no single posting of the Theses, but a general publicizing around the ecclesiastical sites of the city?

One distinct possibility is that this is what Rörer thought had happened because he knew it was what ought to have happened. In the statutes of the University of Wittenberg, drawn up in 1508, approved procedures are laid down for the initiation of academic debates. It was the responsibility of the deans of both the arts and theological faculties to ensure that theses for university disputations were publicized on the doors of the churches in the course of the preceding week. The actual job of posting was assigned to the beadles, university officials whose duties included administrative record-taking, maintenance of discipline among students, and upkeep of the buildings.

Rörer’s choice of the somewhat arcane term valvis for a door, rather than the more common porta, ostium, or foris, may well indicate a direct dependence on the university statutes, which also used this word. In addition, his reliance on the passive construction ‘were posted by’ (propositae sunt) certainly allows of the interpretation ‘were caused to be posted by’, rather than requiring an immediate personal agency on the part of Luther. It would indeed have been unusual, a breach of procedure and etiquette, for a senior professor to have gone around nailing up his own theses.

Here it is also worth pausing to note that the idea of ‘nailing’, commonly used in modern scholars’ English renditions of the Latin verbs affigere and proponere, may be a misleading translation. Neither the Wittenberg statutes nor the notifications of Melanchthon and Rörer make any mention of hammer and nails, whose habitual use would surely have done considerable damage to any wooden door functioning day-to-day as a university ‘bulletin-board’. As the historian Daniel Jütte has established, there is considerable evidence that sixteenth-century people more commonly used glue or wax when pasting up placards and notices in public places.23

None of this rules out the possibility that Rörer was accurately reporting a posting of theses which took place prior to a failed disputation in Wittenberg, or that Luther personally undertook the task of fixing placards to the doors of All Saints and St Mary’s. Yet had he done so, it would have been an unusual, and presumably noteworthy, gesture of personal challenge, which leaves us with the unresolved problem of why neither Luther nor anyone else made mention of it prior to the 1540s.

What is more, Rörer later changed his story. In a set of manuscript notes surviving among the papers of his estate, Rörer wrote that ‘in the year 1517 after the birth of Christ, on the eve of the Feast of All Saints, Martin Luther, Doctor of Theology, issued theses against corrupt indulgences, affixed to the doors of the church which is next to the castle of Wittenberg.’ As the Reformation historian Volker Leppin and others have noted, the wording here is very similar to that used by Melanchthon in 1546, and is in all likelihood directly dependent upon Melanchthon’s account. If Rörer was now deferring to Melanchthon’s supposedly greater knowledge of the case, it strengthens the possibility that his earlier comment, with its assertion of multiple postings, was simply based on an assumption about conventional university procedure.24

Another, undated, historical notice in Latin does not take us much further forward, and does not directly mention the church doors, though it deserves consideration due to the fact its author was in every likelihood Luther’s disciple Johannes Agricola (c. 1492–1566), a student in Wittenberg from 1516 onwards. The note records how ‘in the year 1517 Luther put forward in Wittenberg, a town on the Elbe, certain theses for disputation, according to the old custom of scholars’, adding that ‘his intention was not to abuse or injure anyone’. Agricola wrote that this was something to which he could attest—me teste—leading some scholars to suppose that here, at last, was the elusive eye-witness testimony to the posting of the Theses. But others who have examined the manuscript believe this to be a mistranscription: what Agricola actually wrote was modeste, modestly, indicating the manner in which Luther put forward the Theses. Even if me teste is correct, its placing in the sentence seems to refer to Luther’s motives rather than to his action: his not intending, ‘as I can testify’; rather than his putting forward, ‘as I witnessed’.25

By the middle of the sixteenth century, a belief does seem to have been growing in Wittenberg circles that Luther posted the Theses on 31 October 1517, and that this had been a genuinely notable event, an occasion for reflection and commemoration. It is significant that Rörer’s handwritten note in the 1540 Bible was inserted into a listing of pericopes, the portions of scripture to be read during services on Sundays and feast days. It appears after the entry for Saints Simon and Jude (28 October).26 Paul Eber, a close friend of Melanchthon’s, Professor of Latin at Wittenberg, and later preacher at the Castle Church and pastor of St Mary’s, published in 1550 a calendar of noteworthy historical events, saints’ days and biblical passages, arranged by days of the month. The segment for 31 October contained only one entry, printed in the red ink traditionally reserved in liturgical books for important feasts and celebrations: ‘this day the disputation of Doctor Martin Luther against indulgences was publicly proposed, and fixed to the doors of the church by Wittenberg Castle’. It was, quite literally, a red letter day for Lutherans.

Eber went on to declare how, starting with the contest against the mendacities and corruptions of Tetzel, divine teaching concerning penance and remission of sins was gradually restored to the Church, ‘with many other necessary things and articles of doctrine’. He added that this happened a century after the burning of the Czech reformer Jan Hus by the Council of Constance (in 1415), and that Hus had said to the bishops who condemned him, ‘after a hundred years, you will have to answer to God and to me’.

The prophetic association with Hus was crucial in helping to anchor the ‘start’ of the Reformation in 1517. It was an association Luther himself embraced wholeheartedly in his lifetime. Luther’s opponent, Eck, thought he scored a tactical success at the Leipzig disputation of 1519 by associating Luther’s teaching with that of the notorious Bohemian heretic. Yet months later Luther was telling friends ‘we are all Hussites without knowing it’. In a letter sent from Constance in November 1414, Hus (whose name means goose in Czech) referred disparagingly to himself as a tame bird not capable of great deeds. But he promised that other birds—sharp-sighted falcons and eagles—would follow to tear at the devil and gather and protect the true people of God. His fellow Czech reformer, and fellow martyr, Jerome of Prague, wanted to know what people would make of his own condemnation in a hundred years’ time. Hus’s letter was first printed in 1558. But reports of it must have been circulating orally or in manuscript, for by 1531 Luther had conflated the two utterances and decided that the ‘prophecy’ referred unambiguously to himself. He recounted Hus’s supposed words as ‘now they will roast this goose (for Hus means goose), but one hundred years hence they will hear the song of a swan which they shall have to tolerate.’ In this form—the burning of a goose and the appearance of an incombustible swan—the prophecy became a fixed part of an emerging repertoire of pious reminiscences about Luther; it was repeated in funeral sermons for him in 1546 by his close associates Justas Jonas and Johannes Bugenhagen.27

In a very real sense, the Thesenanschlag was Luther’s own swan song—a defining moment of his career that became talked about only around the time of his death. In October 1553, the theologian Georg Major, superintendent in Luther’s hometown of Eisleben, and a former professor at Wittenberg, preached a funeral sermon for Prince Georg of Anhalt-Dessau, which he shortly thereafter published with a dedicatory epistle to Georg’s brother, Joachim. The text was dated ‘at Wittenberg, on the Vigil of All Saints, on which day, thirty-six years ago, the honourable and learned Dr Martin Luther, of blessed memory, at the Castle Church of All Saints in Wittenberg, while a great dross of indulgences (Ablasskram) was taking place there on All Saints, posted the theses against the indulgence-dross of Tetzel and others’. This, Major added, was ‘the first step towards the cleansing of Christian teaching, for which let there be praise, honour and thanks to God’.

Major was an editor of the Wittenberg edition of Luther’s German Works, itself an important early development in the ‘memorialization’ of the great reformer. He was responsible for the volume, appearing in 1557, which contained a translation of the Ninety-five Theses. Here Major added a marginal annotation: ‘These theses were posted to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, on All Saints’ Eve, 1517.’

Major’s account marks the beginnings of a more emphatic memorialization of 31 October 1517, one which wedded Melanchthon’s attestation of a theses-posting to Luther’s own conviction (expressed in 1541) that the quarrel with Tetzel was ‘the first, real, fundamental beginning of the Lutheran tumult’. It acquires further piquancy from the fact that Major came as a schoolboy to Wittenberg in 1511, and sang in the choir of the Schlosskirche before being admitted to full academic study in the university in 1521. Very possibly, he remembered the Ablasskram, the ritual and fanfare around indulgences, which accompanied the annual display of the Elector’s relics in the Castle Church each 1 November.28 Yet Major does not actually say he was an eyewitness to Luther’s posting of the Theses, and it would be rash to surmise that he was. Crucially, he did not mention the event in letters, or in several published works, prior to Melanchthon’s notice appearing in the second volume of Luther’s Collected Latin Works, from which Major, like Rörer, was very probably taking his cue.

Melanchthon himself quite regularly mentioned the posting of the Theses in letters written on the eve of All Saints, though only in the years after 1546. One such letter, sent in 1552 to Sebastian Glaser, Chancellor to the court of Henneberg in Thuringia, was dated 31 October, ‘when Luther first, thirty-five years ago, put forth his theses on indulgences’. An accompanying letter to the Counts of Henneberg, Georg Ernst and his father Wilhelm, was written on the evening when Luther’s Theses were first ‘angeschlagen’. Melanchthon did not invariably invoke Luther’s action in letters from the 1550s written on 31 October. But when he did, his recollections of the occasion were increasingly thoughtful and reflective.

In September 1556 Melanchthon composed a short manuscript history of the city of Wittenberg, to be sealed in a ‘time-capsule’ and placed in one of the newly restored towers of the city church (from which it was retrieved in 1910). Here, Melanchthon recorded that in 1517 the venerable Doctor of Theology, Martin Luther, announced (edidit) theses ‘which were both piously and academically formulated’. They dealt with true repentance and the faith through which a person is justified, as well as refuting the deceit of indulgences. Linking the Theses-posting to the declaration of the Augsburg Confession (and thus linking himself to the legacy of Luther), Melanchthon wrote that ‘it was from that time on that the abolition of superstitious abuses and the restoration of the pure teachings of the Gospel began, to which the Confession of Faith of the Saxon Congregation attests’. Melanchthon went on prophetically to say that ‘books about this will be passed on to future generations’.29

A year earlier, Melanchthon had written to Paul Eber on the anniversary of ‘the day when Luther first issued his theses which exposed the impostures of indulgences’, and prayed that ‘God would always unify the Church in our communities and in this region.’ Signing off the same day to the Berlin pastor Georg Buchholzer, Melanchthon mused on the great examples of wrath and mercy they had seen in the space of the thirty-eight years since Luther posted those Theses which ‘renewed the doctrine of penance’.30

Wrath and mercy indeed. In the nearly ten years since Luther’s death in 1546, his German followers had crested successive waves of crisis and danger. Only a few months after the great man’s passing, the long-simmering tension between the Catholic Emperor Charles and the Lutheran princes, bound together for protection in the military and political League of Schmalkalden, burst out into open warfare. The result was disastrous for the Lutherans. Charles shattered the Schmalkaldic army at Mühlberg, between Leipzig and Dresden, on 24 April 1547. Melanchthon’s prince, the Elector John Frederick, nephew of Frederick the Wise, was taken prisoner, and stripped of both his territory and his electoral title. Imperial troops occupied Wittenberg, and stood in the Schlosskirche to gloat over the newly erected tomb of Luther. Charles, however, refused requests for it to be destroyed: ‘I do not make war on dead men.’

What Charles would do, however, was impose a punitive settlement on the defeated Lutherans. The Augsburg ‘Interim’ of 1548 restored aspects of Catholic doctrine and practice to the evangelical territories. It was widely resisted, but Melanchthon believed it was possible to compromise without sacrificing core principles, and he worked on the creation of a Leipzig Interim for the Saxon regions, which made concessions in various areas of ceremony and ritual.

The result was a baleful schism within the schism. A movement of pastors who came to be known as Gnesio-Lutherans (original or pure Lutherans) accused Melanchthon and the ‘Philippists’ of betraying Luther’s legacy. They also suspected Melanchthon of moving away from Luther’s firm insistence on the real and literal presence of Christ in the bread and wine of the eucharist to adopt a position closer to that of the Genevan reformer, John Calvin. Gnesio-Lutherans became established at Jena and Magdeburg, while Philippists remained ensconced at Wittenberg.

The divisions were not healed when a renewed tide of war turned against Charles V after 1552. In 1555, unable to impose his will, Charles agreed to the comprehensive ‘Peace of Augsburg’ as a replacement for the Interims. It laid down a famous principle: cuius regio, eius religio (‘your prince, his religion’). The individual rulers of the various German territories would decide whether Catholicism or Lutheranism was to be the sole and official faith in their territories. The Lutheran cause—at first a movement of protest and demands for reform within the Church—was now very firmly an establishment, a separate Church in its own right. But it became so amidst deep and bitter internal tensions. Small wonder if Melanchthon was petitioning God for a spirit of unity, or showing an ever greater concern over custodianship of the contested legacy of Luther’s life and actions.

The posting of the Ninety-five Theses, so Melanchthon wrote to Elector August of Saxony on 31 October 1558, was ‘the beginning of the declaration of Christian teaching.’ ‘The start of the amendment of doctrine’, he called it in a sermon delivered the following day, forty-one years after the Theses were posted and printed and ‘the struggles of the Church began’. In this address, Melanchthon added some further texture and detail to his earlier accounts of the event. The church where the Theses were posted was dedicated to All Saints, and there was at that time ‘great impostures of indulgences’ taking place there. Presumably people took notice of what was beginning to sound like a disruptive and rebellious act. The affixing of the Theses, Melanchthon now reported, happened at the time of the evening vespers service. Indulgences were things of no worth, yet out of them great events were stirred up, and are still being stirred up to this day. ‘Remember, therefore, this day, and at the same time think of these same things!’31

Doors

There is another possible explanation for why a remembered—and quite probably misremembered and indeed imagined—door-posting of the Ninety-five Theses was in the second half of the sixteenth century assuming ever greater significance in the minds of Melanchthon and others of his circle. Increasingly, the religious conflicts and divisions of the age were themselves turning a routine method of sharing information into both a practical and symbolic gesture of protest and defiance.

As we have seen, Luther’s own appeal against Cajetan seems to have been posted on the doors of Augsburg Cathedral in 1518, and the highly provocative burning of the 1520 papal bull was advertised in Wittenberg in this way. Over the following years, it is possible to point to a growing number of examples of church doors being used—by both allies and adversaries of Luther—to make contentious and combative statements to a religiously divided public.

In 1523, Thomas Müntzer, a disciple of Luther’s who was shortly to turn into a bitter opponent, posted letters attacking an antagonist on several church doors in Zwickau. In Minden, a provocative set of theses by the preacher Nicholas Krage, challenging ‘papists’ in the city to public disputation, was posted on the doors of churches in March 1530. Similar sets of overtly anti-Catholic theses were attached to church doors in the Westphalian town of Lippstadt later the same year, in nearby Soest in 1531, and in Osnabrück in 1532, while a satirical anti-Catholic poem was posted a few years later to a church door in Salzburg.

The confrontational habit of posting written challenges was not a solely German phenomenon. Already in 1521, the authorities in Antwerp were threatening punishments and confiscation of goods to supporters of Luther who attacked traditional Catholics in ballads or libels they had ‘written, distributed, or pinned and pasted to church doors or any archways’. Anticlerical verses disdaining the sacrament of confession were pinned to the door of St Peter’s church in Leiden in 1526, and pamphlets and broadsheets denouncing ‘idolatry’ were fastened to church doors in Delft by the anabaptist David Joris at around the same time.32

The papal excommunication of Luther was itself pinned up on church doors across Europe. In England, a radical priest named Adam Bradshawe tore it down when it was posted at Boxley Abbey in Kent. In October 1531, an Exeter schoolmaster, Thomas Benet, posted bills on the doors of the cathedral there denouncing the veneration of saints, and the pope as antichrist. When the pendulum of religious policy swung, Catholics rather than Protestants became secret posters of subversive placards. The most notorious door-fixing of any document in sixteenth-century England was the appearance in May 1570 of the papal excommunication of Elizabeth I on the portal of the bishop of London’s palace near St Paul’s Cathedral—an event which prompted an intense manhunt, and, when the culprit was found, a gruesome execution.33

There is no reason to think any of these were ‘copycat’ door-posts in response to Luther’s original. In a sense, indeed, the opposite may well be true. By the middle years of the sixteenth century, several strands were fusing together: Luther’s own retrospective perception of 31 October 1517 as a seminal date in his confrontation with the papacy; an institutional awareness in Wittenberg of the proper procedures mandated by the university statutes; and the wider emergence of a culture of religious conflict, involving church doors as a site of public spectacle. For Melanchthon, as well as for others, the result was the creation of a notable occasion to mark and ‘remember’.

By the time of Melanchthon’s death in April 1560, memories of the Thesenanschlag had become a fixture in Wittenberg circles, even though some details of the event remained remarkably fluid. In 1563, Melanchthon’s former student Johannes Manlius published a volume of extracts and quotations from his master’s lectures, reprinted several times over the course of the 1560s. Manlius wrote that Luther posted the Theses to the door of the Castle Church on the Feast of All Saints at noon, a detail conflicting with Melanchthon’s 1558 recollection that it was an evening occurrence, but one which may have carried a greater symbolic resonance in tying the event to the high-point of the sun.34

Melanchthon’s account of Luther’s life, containing the foundational reference to the Thesenanschlag, circulated widely in the second half of the sixteenth century, not least on account of its inclusion within the covers of Luther’s collected Latin works. A separately circulating edition, with various other commemorative materials, was edited by Johann Policarius, superintendent of the church at Weissenfels, a short distance south of Halle. He added various short poetic couplets, including one on the ‘Year of Restoring Religion, 1517’:

You drag the work of religion out of the muck, with Christ

As leader, O truthful Luther leaning on the right hand of God.35

Pollicarius’s text appeared in three separate Latin editions and eight consecutive printings between 1548 and 1562. A German translation by the Frankfurt-am-Main pastor Matthias Ritter was produced in 1554, and reprinted another six times before 1561, with a further German translation in 1564. There was an early French translation, printed at Geneva in 1549 and again at Lyon in 1562, as well as a 1561 English translation, which applauded how the work had already been rendered into ‘Spanish and Italian tongues by certain godly persons exiled their natural country’.36

This English version—A famous and godly history containing the lives and acts of three renowned reformers of the Christian Church, Martine Luther, Iohn Ecolampadius, and Huldericke Zuinglius—was the work of Henry Bennet, a native of Calais. Bennet confessed to readers that as soon as he perused the original volume he was ‘ravished with incredible desire’ to turn it into English. But Bennet’s enthusiasm was not equalled by his care as a translator. Melanchthon’s statement that Luther fixed his Theses to the Castle Church pridie festi omnium Sanctorum—that is, on the day before the feast of All Saints—was mistranslated by Bennet as ‘the morrow after the feast of All Saints’.

The mistake had a lasting impact in England, as Bennet’s version of Melanchthon’s account was subsumed wholesale into the ‘History declaring the Life and Acts of D. Martin Luther’ which John Foxe included in his famous Acts and Monuments (Book of Martyrs) in 1563, and retained in three subsequent and expanded editions appearing in the reign of Elizabeth I. The Queen’s Privy Council issued instructions in 1570 that every parish church was to acquire a copy of ‘Foxe’, so for English people who were paying attention it would have seemed that Luther began his campaign of Reformation on 2 November 1517.37

Into the 1550s, however, it was still possible to regard Luther’s posting of the Ninety-five Theses as a detail of little importance, or to overlook it completely. The most important contemporary chronicler of recent events in Germany was the Strasbourg-based humanist and diplomat Johannes Sleidanus, who in 1545 accepted a commission as official historiographer to the evangelical Schmalkaldic League. Sleidanus’s De statu religionis et republicae Carolo V Caesare commantarii (Commentaries on religion and the state in the reign of Emperor Charles V) was published in 1555. In its close attention to factual detail, its extensive use of primary sources, and its tone of objectivity (though masking a selective and deeply anti-Catholic approach), Sleidanus’s work has been hailed as a landmark in the development of historical writing. Largely following Luther’s own version of events, Sleidanus supplied an account of how Tetzel’s extravagances provoked Luther to write to the Archbishop of Mainz and to send with the letter ninety-five theses which, for the sake of a disputation, he had lately promulgated (promulgarat) at Wittenberg. It is unclear whether Sleidanus believed Luther had published the theses, or merely publicized them, but of the door of the Castle Church there is in his account no sign.38

Biographies

The Thesenanschlag was mentioned, but briefly and in passing, in the first full-length Protestant biography of Martin Luther, published at Strasburg in 1556. It was the work of Ludwig Rabus, Lutheran minister there, and the nucleus of a huge multi-volume work, which—like the efforts of John Foxe in England—was intended to celebrate and commemorate the modern martyrs of the Church. Luther was not, of course, technically a martyr. But as the ‘prophet of the German nation’, whose proclamation of the gospel revealed that the last age of the world was underway, he was the pivotal figure of Rabus’s history.

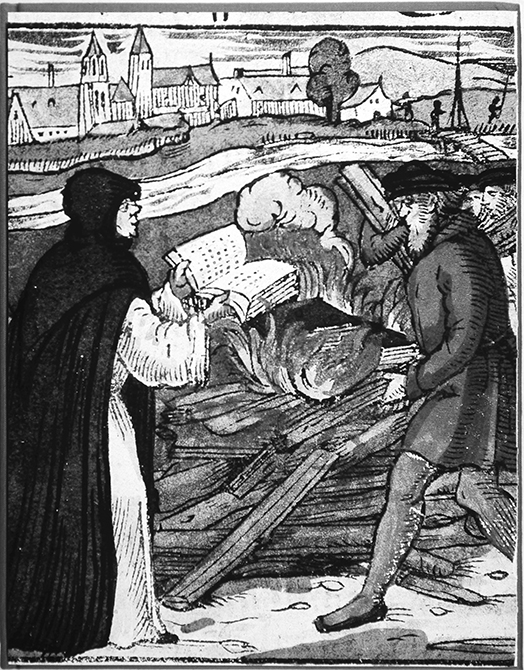

Rabus made use of Melanchthon’s brief life, and did record that Luther posted ninety-five theses on the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg calling for a disputation in person or by exchange of texts. He noted also that this was a hundred years after the execution of Jan Hus. But the real drama of Rabus’s account of Luther was elsewhere, focussing on a series of doughty confrontations with stubborn opponents. The work was accompanied by a set of eleven unsophisticated but arresting woodcut illustrations, pictures which supply for readers, in the words of Lyndal Roper, ‘a basic narrative of what the pious Lutheran needs to know about the reformer’s life’. The selected scenes include the encounters with Cajetan at Augsburg and Eck at Leipzig, as well as two depictions of the Diet of Worms, in one of which Luther is shown uttering the immortal, if uncertain, words, ‘Here I stand, I can do nothing other’. There is also an image of Luther, resplendent in drawn-up monastic cowl, casting the pope’s bull onto the flames with the city of Wittenberg in the background (see Fig. 2.2).39 It quite evidently did not seem to Rabus, or his publisher, that a depiction of Luther positioning his Theses on the notice-board of Wittenberg University would add anything to the artistic or commercial appeal of the work.

Fig. 2.2. Luther burns the papal bull at Wittenberg in 1520, from Ludwig Rabus, Historien der Heyligen Außerwölten Gottes Zeügen (1556).

The assorted claims of Melanchthon, Cochlaeus, and Rabus to be counted as the first real biographer of Martin Luther are contested by Johannes Mathesius (1504–65), an acolyte who studied at Wittenberg, and who recorded some of the Table Talk, before taking up a post as pastor in the Bohemian silver-mining town of Jáchymov (Joachimsthal), near the border with Saxony.40 Between 1562 and 1565 Mathesius preached no fewer than seventeen sermons on the life of the great reformer, published in a single volume in Nuremberg in 1566. The book proved hugely popular, and went through twelve editions before the end of the sixteenth century.

Mathesius’s work was scarcely a biography in the modern sense. It did not seek to explore personality and elicit motive, or to trace changes in character or attitudes. Even more than Melanchthon’s, Mathesius’s Luther was an instrument of God’s purposes, a Wundermann (miracle-man), sent to preach the pure Word against papal darkness in the final era of the world, a latter-day Elijah. This, in short, was a hagiography, a saint’s life, of the kind which would still have been thoroughly familiar to the older members of Mathesius’s Lutheran congregation. At a time of division among Lutherans, Mathesius sought to inspire and unite, devoting considerable attention to the doctrinal substance of the agreed statement of Lutheran faith, the Augsburg Confession, and very little to the actual contents of the Ninety-five Theses, with their perplexingly popish features.41

As to the posting of the Theses, Mathesius reported that this took place at the Castle Church on its ‘Kirchmesse Tag’—that is, the feast of the church’s dedication, All Saints. The implication once more is of a public disruption of a popish festivity. But in undertaking this, Luther was no gratuitous aggressor. Mathesius wrote that Luther was ‘forced’, by his oath and his doctoral position, to post the Theses and have them printed, in response to the ‘Roman and episcopal violence’ employed by Tetzel and his crew.42

As Volker Leppin and Susan Boettcher have acutely observed, there was an inherent ambivalence to the treatment of Luther in many of these laudatory sixteenth-century lives. On the one hand, he was the towering figure without whom the Church would not have begun to reform itself. On the other, there was a reluctance to assert that Luther himself launched or initiated the Reformation, as this was to risk making him a political figure, acting under his own rather than divine disposition. An emphasis on Luther’s motivational restraint was also evident from the Eisleben pastor, and Gnesio-Lutheran, Cyriakus Spangenberg, in sermons he preached and published on Luther, ‘Man of God’, at the rate of two a year (on the anniversaries of his birth and death) between 1562 and 1573. Authors like Mathesius were generally content to report both that Luther had written to Albrecht of Mainz on 31 October 1531 urging him to reform the abuses, and (following Melanchthon) that he posted a printed copy of the Ninety-five Theses on the same day at the Castle Church, without reconciling or even apparently recognizing the contradiction that this involved—though Rabus ingeniously got around the problem by redating the Albrecht letter to 1 October.43

We have reached and are passing the point of transition between what has been called ‘communicative memory’ (informal and everyday, handed on through personal recollections, shared stories, and daily interactions) and ‘cultural memory’ (the process of constructing and maintaining a group identity with reference to rituals, images, and texts).44 Mathesius was the last of the major chroniclers of Luther’s life to have known the man personally. Towards the end of the sixteenth century Luther was becoming a historical figure, and a magnet for myth.

The passage of time, and a reliance on earlier texts, could certainly breed carelessness. A 1586 life of Luther by the Strasburg pastor Georg Glocker reported that the posting took place ‘on All Saints Day’, not the eve of the feast. Georg Mylius (1548–1607), Professor of Theology in Wittenberg, no less, published a sermon in 1592 in which he said that Luther started to confute ‘popish abominations’, and ‘publicly posted the sentences or theses of his disputation at the castle Church here in Wittenberg’ in the year 1516.45

Yet squeamishness about admitting that Luther’s action had indeed started ‘the Reformation’ was starting to dissipate. An updated version of the Chronicle of Johan Carion, taken in hand by Melanchthon’s son-in-law Caspar Peucer, and published in German translation at Wittenberg in 1588, asserted unapologetically that the posting of the Ninety-five Theses was the ‘occasion and cause’ of the reform of the Church. The debate over indulgences initiated by the posting of articles on the Schlosskirche was, wrote the Wittenberg-trained minister Paul Seidel in 1581, ‘the beginning and original cause of the Reformation and why the pure teaching of the Holy Gospel is once again among us’.46

For the Weimar pastor Anton Probus, preaching in 1589, 31 October 1517 was the anniversary of a spiritual liberation of consciences and souls from the ‘gruesome tortures, cudgellings (“Stockmeisterei”) and thief-hangings of the papacy’. For, more than seventy-two years ago now,

Dr Martin Luther, driven and aroused by God’s spirit, started to write against papistry, and in Wittenberg posted 95 propositions or theses to the door of the Castle Church, in which he answered a preaching monk, John Tetzel, and with God’s Word powerfully struck down his flea market and indulgence dross.

Here, any notion of Luther writing courteously to his ecclesiastical superiors has been eclipsed by the righteous anger of an inspired prophet of God. Seidel too laid emphasis on Luther’s own powers of action in undertaking the Thesenanschlag—his ‘bountiful spirit, rigorous, just and meet’—as did the Leipzig theologian, Nikolaus Selnecker, in a biography of 1576, though Selnecker was careful to insist that when Luther posted his Theses to the Schlosskirche he did so ‘not to defend his own person, but the truth’.

There was an added incentive, around the turn of the 1580s, to emphasize Luther’s unique status as an arbiter of Christian truth, and also to anchor it in the context of the University of Wittenberg—Philip Melanchthon’s town just as much as it was Martin Luther’s. Selnecker and Seidel were both heavily involved in trying to win adherence to the Formula of Concord, a document drawn up in 1577 with the aim of bringing back into harmony the warring ‘Gnesio-Lutherans’ and ‘Philippists’. In this aim it was partially, but only partially, successful.47

Martin Luther, like other charismatic religious figures of the later middle ages, preached reform, reformatio. To conservative opponents, he was another in a long line of destructive and misguided individuals who thought they knew better than the guardians of truth: a heretic. Only gradually did the notion emerge that the events of the early sixteenth century constituted some kind of unique historical watershed in the history of Christianity: the Reformation. But that idea was starting to receive expression in the late sixteenth century, and in the view of its advocates was closely linked with the exceptional status of Martin Luther as an inspired instrument of God.

It was, unsurprisingly, a view appealing most strongly to those Protestants who identified themselves as Luther’s heirs. In the increasingly ‘confessionalized’ world of late-sixteenth-century Europe, Lutherans were the rivals, not just of Catholics, but of the followers of John Calvin and other Protestant leaders collectively known as ‘the Reformed’, as well as of various splinter groups of spiritualists and radicals. A carved stone from a domestic dwelling in sixteenth-century Wittenberg, now preserved in the Lutherhaus Museum there, bears an uncompromising message:

Gottes Wort und Lutheri Schrift

Ist des Bapst und Calvini Gift.

(God’s Word, and the writing of Luther

Is the poison of the pope and Calvin.)48

For all that, non-Lutherans were often willing to acknowledge Luther’s pivotal role. In England, the Calvinist John Foxe headed a section in his martyrology, ‘Here beginneth the reformation of the church of Christ, in the time of Martin Luther.’ But a mindset which saw God himself as the prime mover in the events of history might hesitate to attribute too much to one individual, and might lean towards alternative and longer timescales. Matthew Sutcliffe, another English Calvinist, writing at the beginning of the seventeenth century, was equally attuned to the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century dissidents John Wyclif and Jan Hus as men who ‘have laboured in the reformation of the Church.’49 Across Europe, ‘Reformation’ was often seen, not as a past event to be commemorated and celebrated, but as an unfinished, ongoing challenge and struggle.

The urge to commemorate past contests and triumphs is not incompatible with chronic anxieties about the present. On the contrary, it is often integral to them, as attempts are made to shore up a group identity by drawing upon a store of inherited symbols and traditions. Among Lutherans, the call to ‘remember 1517’ as a pivotal moment of history was by the later sixteenth century being made into a rallying-cry. The process began in the lifetime of Martin Luther, and indeed with Luther himself. But we should not fall into the trap of thinking it was the self-evident signification of that year as it unfolded in actual time.

If we could somehow stop the historical clocks in December 1517, what in fact would we have? A high-minded dispute (of a kind that had been rehearsed before) about one subsidiary aspect of the pastoral theology of penance; a moralistic friar petitioning his ecclesiastical superiors about alleged abuses within their jurisdiction; the same friar’s attempts to instigate a customary kind of academic disputation; the wheels of disciplinary procedure against him starting, very slowly, to turn.

It was a still less likely eventuality that the posting of the Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg would come to mark an important—ultimately, the defining—place in this historical pagination of memory. It was, as we have seen, no part of Luther’s own narrative of events: most likely because it did not happen at all, or if it did, because it was an unremarkable occurrence, in no way comparable to the actual writing of the Theses, or the temerity of sending them, albeit courteously, to the Prince-Archbishop of Mainz.

In the generation after Luther’s death, and largely due to the influence of Philip Melanchthon, this non-occurrence of a non-event gradually transformed itself into a verifiable historical fact—a proof of the adage that while history may repeat itself, historians repeat each other. Its meaning too was starting to mutate: a circumstantial detail of Luther’s quarrel with Johan Tetzel and his backers was coming to be seen as an act of courageous defiance, and of weighty symbolic significance.

Yet this was very much still a piece of Lutheran pious reminiscence, and within Lutheranism, a largely regional one. The majority of writers and preachers who paid any attention to the event seem to have had a Saxon background, and very many of them boasted close Wittenberg connections. Even within Germany, at the close of the sixteenth century, 31 October 1517 was not widely seen as a date of towering and unique significance. An annual celebration of ‘deliverance’ from a benighted popish past was indeed an increasingly common feature of collective and civic life in Protestant territories. But a variety of dates were chosen locally to mark this occurrence, very often the anniversary of the moment when evangelical sermons were first preached or Protestantism was received as the official religion. In Braunschweig this commemoration was kept on the Sunday after 1 September; in Hamburg and Lübeck on Trinity Sunday, the first after Pentecost.

A number of places marked with special church services the day of Luther’s birth (10 November), his baptism (11 November), or death (18 February). Across southern Germany it was common to commemorate 25 June as the ‘beginning’ of the Reformation: the day on which the Augsburg Confession was formally presented to the Emperor. Publication in German of the hard worked-out Formula of Concord as the Book of Concord, on 25 June 1580, was timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of this seminal occasion. The formal reading of the Augsburg Confession to Charles V by the Saxon Chancellor Christian Beyer at the diet of 1530 was the subject of a much-reproduced sixteenth-century engraving. It was also the theme of a magnificent painting commissioned in the early seventeenth century for the chancel of St George’s church, Eisenach.50 By contrast, no one at all had yet thought to depict the posting of the Ninety-five Theses in any kind of visual form.

In 1600, the English writer Samuel Lewkenor published a book containing lively descriptions of foreign university cities, for the benefit of ‘such as are desirous to know the situation and customs…without travelling to see them’. In the early years of the sixteenth century, Wittenberg might have struggled to earn inclusion in such a pan-European survey of higher education, but it was now a university playing very much in the big leagues. If Lewkenor’s readers were London theatre-goers, they were soon also to learn that a fictional Prince of Denmark had studied there, along with his friend Horatio. The Wittenberg doctors, Lewkenor observed, were ‘the greatest propugnators of the Confession of Augsburg’, and, since its foundation in 1502, the place ‘in this latter age is grown famous, by reason of the controversies and disputations of religion, there handled by Martin Luther and his adherents’. In none of Lewkenor’s topographical or scholarly scene-setting, however, did the Castle Church or its doors rate so much as a mention.51 At the turn of the seventeenth century, the triumph of the Thesenanschlag lay firmly in the future.