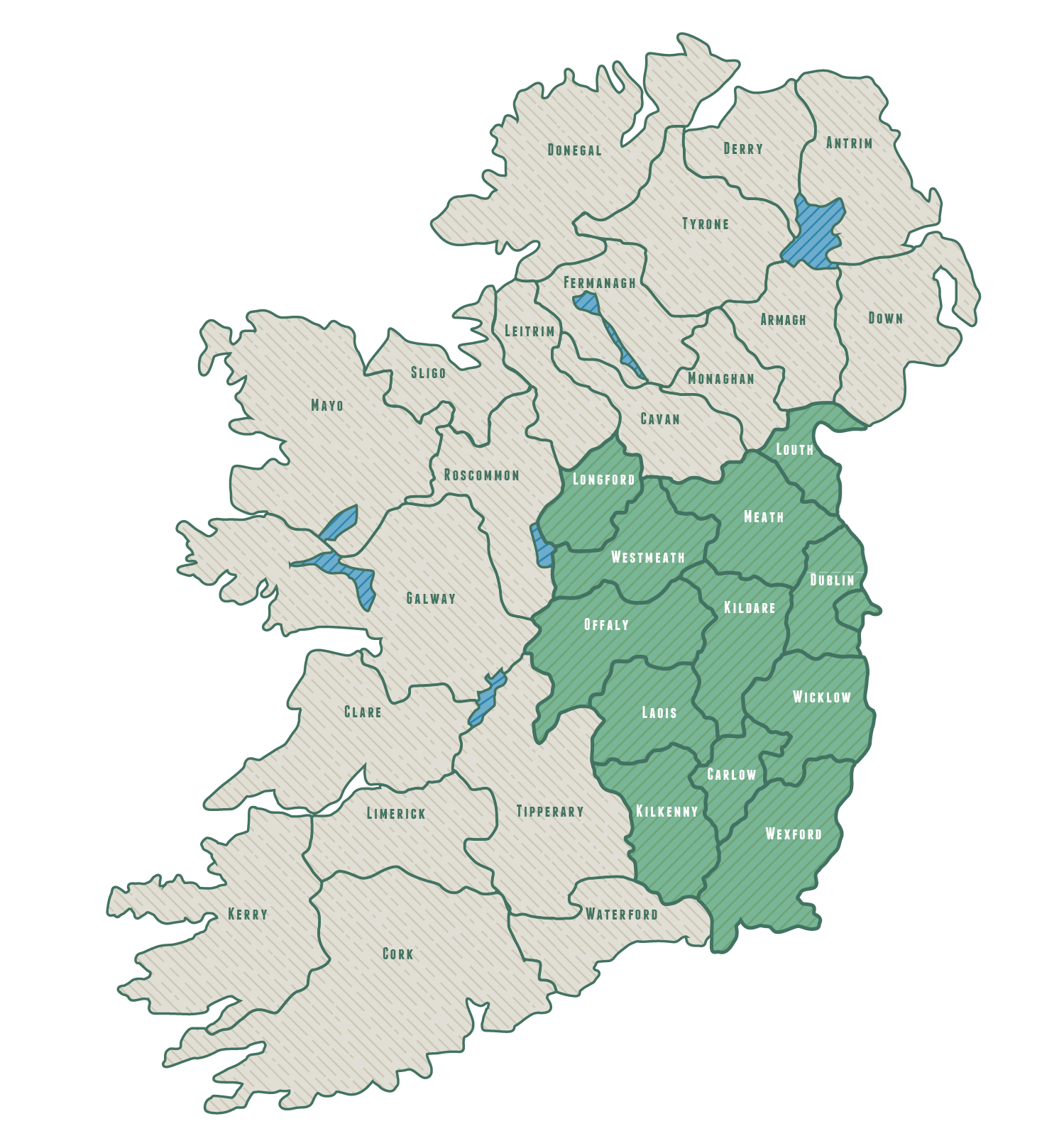

THE COUNTIES OF

LEINSTER

Carlow |

Louth |

Dublin |

Meath |

Kildare |

Offaly |

Kilkenny |

Westmeath |

Laois |

Wexford |

Longford |

Wicklow |

There are more counties in Leinster than any other province in Ireland. What’s more, one of those counties is Dublin—which is a world of its own; possibly several. So already you have a dilemma: How are you going to fit it all in?

Let’s start with the fair city herself. Dublin offers everything any major modern European capital city does: art, culture (high and low), architecture, history, literature, entertainment, shopping, nightlife—the lot. And it does all that with a bit of a swagger and panache. If you can’t enjoy Dublin, you may unfortunately have been born to the wrong species. It’s the only rational explanation. The new city, with its gleaming citadels of glass and steel, sits comfortably alongside old Dublin—what most of us think of as real Dublin—with its cobbles and street markets. And of course, its pubs. Key sights are Trinity College and the Book of Kells, Merrion Square, and the National Gallery (be sure to see the Jack Yeats and Louis le Brocquy paintings). Take a stroll around Temple Bar. It’s busy but worth it. Grafton Street is prime retail territory, with lots of interesting side streets to explore.

If you never got around to finishing Ulysses—first of all, shame on you—try it again while you’re here. There are lots of James Joyce trails in the city, as well as events and readings going on all the time, which will help bring the whole wondrous thing to life.

From the buzz of Dublin, head south into beautiful, peaceful County Wicklow. The landscape is lush here, which is why it’s known as the Garden of Ireland. There are many walking trails, empty beaches, and historic sites such as the heart-stoppingly lovely Glendalough.

Keep going south and you’ll reach Wexford, which was once a Viking settlement (yes, they were here, too). Irish history buffs will enjoy discovering the central role this vibrant, friendly town played in so many key events. Wexford is also home to an internationally renowned opera festival every October.

If you’re looking for a different kind of entertainment, look northwest to Kilkenny—chances are, you’ll find some kind of festival going on. Whether it’s arts, comedy, theater, or music, they do enjoy a get-together there all year round. Why not join them? You’ll be most welcome.

Muiredach's High Cross—the largest Celtic cross in Ireland, in Monasterboice, County Louth.

Older than the pyramids: the mysterious Neolithic Newgrange in County Meath.

Glendalough: One of the most famously beautiful places in Ireland.

Many countries are really two countries: There’s the capital (with its hinterland) and then everything else. In France, for example, there is Paris and then there is what is described as en province, i.e., not-Paris. We’ve a little of that in Ireland, too: There’s Dublin and not-Dublin.

Our capital city is a hefty presence, as it should be. That presence, and the rest of the accompanying county (also conveniently called Dublin), is in the province of Leinster. The story of Dublin distilling is long and engrossing. It was, after all, the center of the whiskey-making world for the best part of a century. That has tended to skew the tale of the rest of the province. But a lot of whiskey has also been distilled in not-Dublin, going all the way back to the arrival of the medieval monks with their alembics. One of the first written records of uisce beatha in Ireland speaks of Drogheda, in County Meath. Ireland’s oldest licensed distillery is the legendary Kilbeggan, in County Westmeath. And Leinster is also home to not one but two of the distilleries that have been instrumental in the resuscitation of the once-moribund whiskey industry: Great Northern and Cooley. What’s more, these are connected by the same figure, the charismatic John Teeling.

With Cooley, Teeling brought back to life several long-vanished Kilbeggan brands. And with Great Northern, he has created a large contract distiller able to produce grain, double- and triple-distilled malt, and pot still whiskeys. These, among other things, constitute the new-make spirit many of the start-up distilleries need. And so the wheel turns.

Numerous interesting newer producers, such as Boann and Walsh, have set up in Leinster. The beautiful Powerscourt Estate down in Wicklow now has an impressive-looking distillery under way, as does the equally historic Slane Castle Estate. The latter is backed by the giant Brown-Forman group, owner of Jack Daniels.

When it comes to the story of Irish whiskey-making, of the four provinces of Ireland, Leinster is perhaps the trouble child—the one that has given the most heartache. It’s the one that promised so much, delivered so much, and lost so much. Every crazy twist in the tale has been played out here and writ large for the world to see. Its soaring heights were the highest and its plummeting lows the lowest. But Leinster’s recovery contains several of the most vital moving parts of the engine driving Irish whiskey today. We couldn’t have got to this point without it. And, to a large extent, what happens in Leinster will determine where we go from here.

In Leinster, there’s more to distilling than Dublin. A lot more.

Oh, if barrels could talk . . .

It never was much to look at it. Then again, the old Ceimici Teoranta plant outside Dundalk was never in it for the glamour. It was one of a number of facilities built by the Irish State years ago to produce industrial alcohol and neutral spirit for the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors. By 1987 it had been closed for some time and looked likely to stay that way. After all, who would want it?

John Teeling would. He’d been quietly working on a plan to kick-start the independent spirit of Irish distilling, which for years had been largely concentrated in the hands of a few multinational groups. The Dundalk operation—which he renamed Cooley—offered the ideal setting to put the plan into action. When he refitted the plant as a whiskey distillery, it was the first new one built in Ireland in over a century, and it broke the de facto monopoly the Irish Distillers Group had held since the 1970s. Within ten years of opening, Cooley won a major international quality award: a first for an Irish distillery.

Right from the start, Cooley was a place of true innovation. An early indication of the subversiveness to come was when Teeling rejected the received wisdom that triple-distillation was the only game in town, as far as Irish whiskey was concerned. Instead, he adopted the Scotch model of double-distilling in copper pot stills (which he sourced from the long-closed Old Comber distillery in County Down). He also had the plant’s original industrial column stills refurbished to produce grain whiskey for blending. What was he doing with all this product? Selling it as sourced whiskey to retailers as private-label whiskey and to other distilleries, especially to the new kids on the block.

Once Cooley was operational, the next and main phase of Teeling’s plan could go into effect: reviving once-forgotten brands such as Locke’s, Tyrconnell, Kilbeggan, and—controversially—a peated single malt, Connemara, which was seen as an attempt to take on the more popular style of Scotch. If it was a gamble, it was a good one. (As Teeling memorably said, “Risk isn’t a philosophy, it’s an addiction.”) Since its launch in the 1990s, Connemara has successfully proved Teeling’s instincts correct, and the distillery’s revival of historic lines has demonstrated a profound understanding of the traditions of Irish whiskey-making. In a further break with convention, Cooley also opted to bottle a single grain, Greenore. This has since been rebranded as Kilbeggan Single Grain and continues to be a very popular addition to the range.

All Cooley maturation—which, except for special finishes, is done exclusively in ex-bourbon barrels—takes place on-site at Cooley and at the Kilbeggan distillery in County Westmeath.

In 2012 Cooley was acquired by Beam International and is now part of the global Beam Suntory group. And the Teeling family’s subversive instinct has moved on. After Cooley, John founded Great Northern—Ireland’s largest independent distillery—nearby in Dundalk, while sons Jack and Stephen opened their own award-winning operation in Dublin, the first new distillery in the capital in 125 years.

Cooley may have begun in inauspicious surroundings, but its history and legacy have been key factors in shaping Irish distilling today.

FIRST DISTILLATION

1989

stills

2 Pot Stills (Wash Still: 16,000L, Spirit Still: 16,oooL)

3 Column Stills

LPa

4 million

Whiskey STYLES

Single Malt, Pot Still, & Grain. Plus Peated

Visitor center/tours

No

Tyrconnell Single Malt

ABV: 40%; also port, sherry, and Madeira finishes, all ABV: 46%

Connemara Peated Single Malt

ABV: 40%

Kilbeggan Blended

ABV: 40%

Kilbeggan Single Grain

ABV: 43%

Locke’s Single Malt

ABV: 40%

Great Northern: It’s not art, it’s commerce.

There’s a lot of romance in whiskey; poetry even. No doubt it has something to do with the passion involved in it—and oh, the waiting, the waiting . . . There’s something akin to longing there. And the word itself even sounds a bit wistful.

Combine that with the quasi-mystical alchemical nature of the process, the coaxing of an extraordinary thing from the most commonplace ingredients: grain, yeast, water. The art of blending and the unquantifiable magic can all make even the hardiest souls grow a little misty-eyed.

But not here. For this is not art but commerce. And that’s no bad thing.

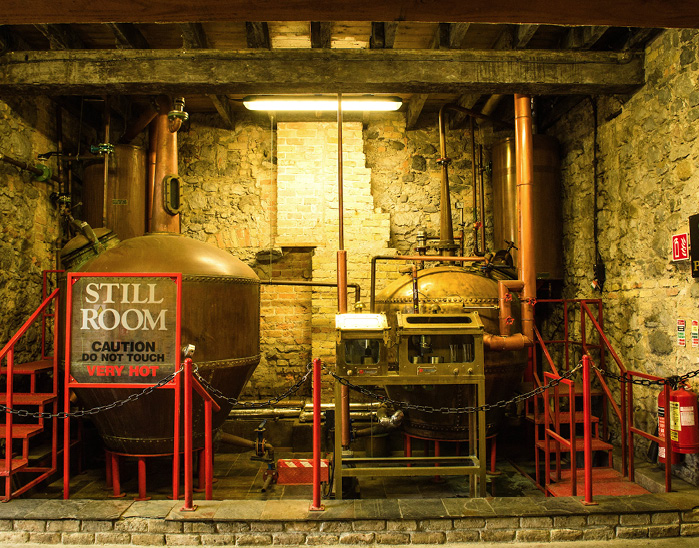

Established in 2015, Great Northern Distillery is today Ireland’s largest independent distillery—by quite some margin—producing three styles of whiskey: malt, grain, and pot still. It was originally built for volume, as a former Diageo brewery producing Guinness and ale, and subsequently converted solely to make Harp lager. They run both pot stills and column stills here, and make grain, double- and triple-distilled malt, peated malt, and pot still whiskey.

Unsurprisingly, there’s no visitor center here. But we’re featuring Great Northern because of its central importance to Irish whiskey-making today. Its key market is private labels and contract distilling, with some retail own-label production, though the distillery has actually recently released its first own bottling—Burke’s Irish Whiskey, an exclusive, cask-strength single malt.

Great Northern also provides stocks for smaller distilleries. So, for example, when a brand-new distillery business is launched fully equipped with maturing whiskey stocks, that’s one possible explanation of where the stocks came from. There are few sources of new-make spirit in Ireland: The pot stills and column stills here are two of them. As a contract producer, Great Northern will provide your shiny new distillery with new (or aged) spirit to your requested standard and profile. It’s a sort of bespoke whiskey tailoring service. They can even provide casks. Or just bring your own along and they’ll fill them for you.

Great Northern is headed by the maverick, engaging, and teetotal John Teeling, something of a titan of modern Irish distilling. He is the man behind the transformation of the Cooley Distillery and the revival of iconic, long-lost brands such as Kilbeggan and Tyrconnell. (His sons run the new and award-winning Teeling Distillery in Dublin. In fact, the family involvement in the business goes back as far as the eighteenth century.) John Teeling has been a central character in many of the key developments of Irish whiskey over the past thirty years or so. He’s seen it all, and has few illusions. “We’re now seen as visionaries. We used to be seen as eejits.” (He didn’t actually say eejits, but you get the picture.)

There may be no illusions about whiskey distilling here, but there is no philistinism either. There are depths of knowledge and experience in Great Northern that few can match anywhere. There is an in-house laboratory that monitors quality and models the spirit profiles for clients. The equipment is state-of-the-art. The commitment to quality is unwavering and borders on the obsessive. Today, just like every day, at Great Northern they will go about the business of producing the finest spirits they can possibly make. As for the poetry, they’ll leave that to others.

first distillation

2015

STILLS

3 Pot Stills (Wash Still: 50,000L,

Intermediate Still: 26,000L, Spirit Still: 26,000L)

3 Column Stills

LPA

16 million

Whiskey STYLES

Single Malt, Pot Still, & Grain. Plus Peated

VISITOR CENTER/tours

No

BURKE’S 14-YEAR-OLD SINGLE MALT

ABV: 59%

Some of the busiest fermenters in Ireland.

The dean of distillation: John Teeling, still talking whiskey.

A mash tun and a lauter tun.

Pat Cooney is an exceptionally fine whistler. And whiskey-maker. Put the two together and . . .

In the history of Irish whiskey, Drogheda holds a particularly important place. In fact, several of them. One of the first written records of the spirit in Ireland references the town. By the late eighteenth century, there were nearly twenty distilleries here alone. A hundred years on, one of these was, by quite some measure, among those producing the greatest volume of whiskey in ireland.

And there’s one other interesting footnote. In 1812 a young inspector for Excises and Taxes began working here, studying the work of distilleries. His name was Aeneas Coffey. Evidently, he learned well.

When Boann Distillery becomes fully operational, its whiskey will be the first produced in Drogheda in over fifty years. It will be the work of the Cooney family—Pat and his wife, Marie, their daughters, Sally-Anne and Celestine, and sons, James, Peter, and Patrick Jr. They’re all involved in the venture. And there’s a lot of expertise in that team. Pat senior is a veteran of the Irish drinks industry, having spent decades building up what was a small bottling concern into Gleeson Group, a major drinks branding and distribution business. The family’s holding company, Na Cuana, also includes Boyne Brewhouse, Adam Cidery, and Merrys Irish Cream Liqueur.

The stunning fifty thousand-square-foot building (which was once a car showroom) opened in 2016. It already houses a craft brewery and taproom, with plans for a restaurant, visitor center, and gift shop. The brewery is operating, creating a range of beers, as well as ciders with apples from the company’s own orchards. (In time those orchards may also produce a Calvados.)

The heart of any whiskey distillery is of course the stills. Boann’s are high-tech, handmade copper stills with reflux control coils in the neck. As a result, the theory goes, the spirit is exposed to more copper than in a standard pot still.

John McDougall, famously the only man to have distilled all five types of Scotch whisky (single malt, blended malt, single grain, blended, and blended grain), as well as Irish, is a consultant for Boann. A former pupil of his, Aine O’Hora, is the resident distiller.

The distillery has a mission to be 100 percent natural and 100 percent Irish. The water comes from Boann’s own well and is part of a closed-loop recycling and heat recovery system that also feeds the packaging lines and the restaurant. In due course it will also supply the visitor center and offices. Rainwater is harvested and used to cultivate gin botanicals. (They have plans here for a hedgerow gin and another with a cider base.) All by-products—the pot ale and spent grains, etc.—are returned to the local economy as animal food.

The family’s own extensive wine cellars have put at the distillery’s disposal an unusually wide range of casks—including, of course, bourbon, sherry, rum, and port, but also Burgundy, Bordeaux, Sauternes, Tokay, Madeira, and Marsala.

There is sourced whiskey maturing in these barrels at the moment. At the time of our visit, the distillery had some 250 barrels of grain and 200 of malt whiskey aging in oloroso casks in their warehouse in Clonmel. The setup at Boann is no artisan, cottage-industry arrangement. It is technically impressive and well-considered. It happens to have impressive views, as well.

According to Celtic mythology, Boann was the goddess of the River Boyne, around which the town of Drogheda grew. She’s been quiet for a long time. But rumor has it, she’s coming back, and in quite some style.

first distillation

2018

STILLS

3 Pot Stills (Sunshine: 10,000L,

Sally: 7,500L, Celestine: 5,000L)

LPA

250,000

Whiskey STYLES

Single Pot Still

VISITOR CENTER/Tours

Yes

The whistler 7-year-old blue note single malt,

ABV: 46%

The whistler 10-year Single Malt,

ABV: 46%

Pat Cooney, whiskey-maker and whistler.

Boann, the river goddess, is back in business.

Slane’s stills look as though they sprouted through the floor of the

old stable block.

History is everywhere here. Slane Distillery is located within the vast Slane Castle estate—some 1,500 acres of grounds, gardens, forest, and farmland in the ancient Boyne valley.

The castle itself is cradled in a natural amphitheater, which has provided the backdrop for huge rock concerts featuring everyone from the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen to David Bowie, U2, and Guns N’ Roses—all courtesy of the dashing Lord Henry Mount Charles, the 8th Marquess Conyngham.

The distillery is a joint venture between the Conyngham family, which has owned the estate for over three hundred years, and the Kentucky-based Brown-Forman spirits group, owner of Jack Daniels. Cofounder Alex Conyngham, son of Lord Henry, is overseeing the completion of the distillery, which has been designed to be a near-zero-waste enterprise. There is an anaerobic digester—heat and water are recycled, and any organic by-products are returned as animal feed, etc.

At the time of our visit, the distillery was still under construction in the castle’s 250-year-old former stable block. When completed, the facility will comprise what is known as a heritage room, highlighting the history of the estate and the region; the barley store; the cooperage; the warehouse; and, of course, the stills. Maturation is currently managed off-site but will move to the distillery when the site is fully operational. Most of the barley for the distillery will be sourced from the Slane estate.

New-make spirit has already been laid down according to Slane’s recipe and profile, and is being aged in three different cask types. The Brown-Forman cooperage has supplied virgin and seasoned bourbon barrels, while oloroso sherry casks have been sourced from Jerez, Spain. It’s said that the virgin wood, which has a medium char, contributes toasted oak and vanilla to the profile. The bourbon barrels lend a caramel-butterscotch sweetness, while the sherry casks offer dried fruits and spice notes.

The whiskey is presented in a distinctive black bottle. (This is a reference to the old stable block itself. When the restoration work began, the foundations were discovered to contain a lot of black glass dating back several hundred years.)

Slane is Brown-Forman’s first venture into Irish whiskey, and the first distillery it has built outside of the United States. The group has invested substantially in the project—a clear indication of both commitment and viability. For this is no artisan, boutique venture. Slane Distillery may be starting small, but it is aiming very high indeed.

FIRST DISTILLATION

2018

STILLS

3 Pot Stills (Wash Still: 13,000L,

Intermediate Still: 13,000L, Spirit Still: 6,000L)

6 Column Stills

LPA

1.4 million

Whiskey styles

Single Malt, Pot Still & Grain Whiskey

Visitor center/tours

Yes

SLANE BLENDED IRISH WHISKEY

ABV: 40%

Yes, it’s really a castle.

Three of Slane’s six column stills.

The spirit safe: crucial for assessing the distillate coming from the still.

Powerscourt: a distillery with spectacular grounds attached or spectacular grounds with a distillery attached? Both.

From its stunning setting in the Wicklow Mountains to the scale of its ambition, everything about Powerscourt Distillery is capital-G Grand.

Still under construction at the time of our visit, the distillery is a joint venture with the historic Powerscourt Estate, which itself attracts over half a million visitors a year to its grounds, castle, and beautiful gardens. The estate has set aside 120 acres of premium barley to supply the distillery. The pure water source is on-site, too.

The home of the distillery will be the estate’s old Mill House, which is being restored and extended. It is a substantial building with a large old bell outside that was once used to summon workers from the fields. The site will also house a visitor center, a bar, and a café. Several levels of tour will be offered, from general to a fully immersive VIP experience. Four years in the making, Powerscourt Distillery is the brainchild of financiers Gerry Ginty and Ashley Gardiner, and Sarah Slazenger, managing director of the Powerscourt Estate.

The goal for this field-to-glass venture, says Gerry Ginty, can be expressed in two key attributes: “Authenticity and taste. With certified mineral water from the estate and barley grown on the estate, we are working to create something extra special—the ultimate Irish whiskey.” A capital-G Grand Ambition indeed. And the signs are already encouraging.

The master distiller here is the award-winning (and Whisky Hall of Famer) Noel Sweeney, formerly head blender at Cooley. The first release is actually sourced whiskey produced by Noel himself during his time at Cooley. The distillery has decided that, when the time is right, it will release its first expressions—two rare single malts, a ten-year-old and a fourteen-year-old—under the brand of Fercullen, which is the ancient name for the townland on which the modern-day Powerscourt Estate sits. It will be the first artisan pot still whiskey produced in Wicklow since the eighteenth century. Currently working on additional profiles and experimenting with finishes—including Madeira, port, sherry, and rum—Noel will oversee all aspects of spirit production and whiskey maturation at the distillery. One thing the estate is not short of is space, so warehousing also will be handled on-site.

Given its remarkable location, Powerscourt can reasonably expect to figure prominently in the burgeoning Irish whiskey tourism industry. The distillery will also be contributing to the rural economy in this part of County Wicklow—and, of course, producing very interesting Irish whiskeys, too. The skills and the pedigree are there. All it needs is what whiskey always demands: time. We recommend you give it some of yours.

FIRST DISTILLATION

2018

STILLS

3 Pot Stills (Wash Still: 13,000L, Intermediate Still: 8,500L, Spirit Still: 6,000L)

LPA

800,000 projected

WHISKEY STYLES

Single Malt & Pot Still

Visitor center/tours

Yes

Fercullen 10-year-old single malt

Fercullen 14-year-old single malt

From field to glass: The journey starts here.

Fanboy Tim and master distiller Noel Sweeney.

Powerscourt’s three pot stills by Forsyths.

Finding Ireland’s oldest licensed distillery: If you can read the stack, you’re there.

What was happening in the world back in 1757? History, mostly. William Blake was born. Paul Revere got married. And in Kilbeggan they were making whiskey. They still are. However, life here in Ireland’s oldest licensed distillery has not always gone smoothly since the eighteenth century. Indeed, quite far from it.

The story is a saga of ambition, revolution, scandal, failure, hope, rebirth—and above all, families.

The McManuses started it all. Their new distillery had everything going for it: water from the River Brosna, grain from local farms, and turf from the surrounding bogland to power the stills. Things went well, but by the turn of the century, the distillery had changed hands. The Codd family invested in it and capitalized on the newly opened Grand Canal to unload materials and move stock more efficiently than before. The distillery prospered and the reputation of its premium pot still whiskeys grew. Then a temperance movement took hold and swept the nation. The distillery declined, but its assets were bought by yet another family, the Lockes, in the mid-1840s. They revived the business and began exporting to England and the United States. The strategy worked—until a perfect storm of disasters arrived in the early half of the twentieth century. Prohibition in the United States, a world war, the Irish War of Independence, trade war with Britain, and then another world war effectively killed off not just Kilbeggan but practically the entire Irish distilling industry. In the aftermath, the Locke family remained nominally in charge, but by 1957 they’d had enough and gave up the fight.

For the next thirty years the distillery lay silent. During that time, it served various functions, including a pig farm, an engineering plant, and a warehouse. But—and this is crucial—the license to distill never expired, thanks to the local community, who kept it up-to-date. In the early 1980s that same community restored the distillery as a whiskey museum. In 1987 yet another family—the Teelings, who had just set up Cooley Distillery—acquired the Kilbeggan license, took over the museum, and built a new distillery on the site. In 2007, some 250 years after it first started, Killbeggan started to distill again, using a 170-year-old still from the old Tullamore distillery.

And in a sense, it was as if nothing much had changed. The same traditional methods, mashing in oak tuns, fermenting in pine vats and original oak vats, even a pot still from over a century and a half ago—all were put to use again. John Teeling helped revive some of the distillery’s iconic brands and created the Kilbeggan brand for the German market. A new chapter began; accolades began to arrive, and they have kept arriving. Kilbeggan Distilling Company is now the most-awarded Irish distiller ever. The vast maturation warehouse began to fill up.

In 2012, the global Beam Suntory group bought Kilbeggan. This has helped bring the whiskeys of this historic distillery to a worldwide audience. The visitor experience at Kilbeggan is exceptional, from the restored waterwheel that once powered the entire site, to the stills and the tasting. It is a place that is utterly authentic, proud of its past—and equally optimistic about its future.

first distillation

1757 & 2007

stills

2 Pot Stills (Wash Still 3,000L,

Spirit Still: 1,800L)

lpa

Less than 100,000

whiskey styles

Single Malt & Pot Still

Visitor center/tours

Yes

Kilbeggan DISTILLERY RESERVE SINGLE MALT

ABV: 40%

Wheels within wheels within wheels . . .

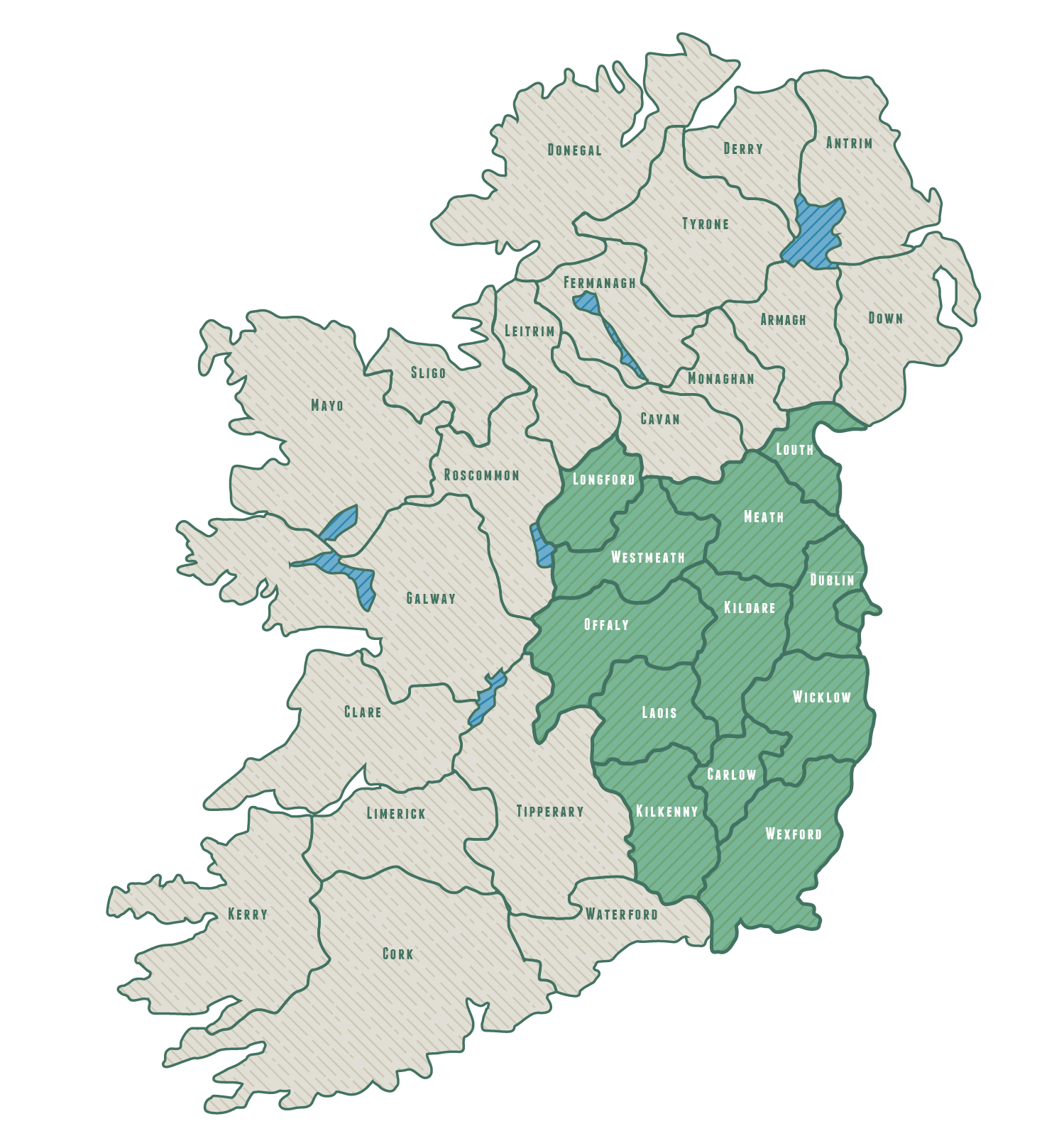

Double-distillation: The still on the right is 170 years old.

By the time you’ve finished counting all the barrels, some of the whiskey in them will be mature.

When it comes to Tullamore, there’s definitely something special about the number three: triple-distilled, triple-blend, triple-matured. And of course, that triple-letter suffix: D.E.W.—for Daniel Edmund Williams.

williams started work at the distillery in 1862 as a stable boy when he was just fourteen, ending his career sixty years later as owner. In 1893 Tullamore D.E.W. became the name of the original pot still whiskey the distillery produced (along with the enduring slogan “Give every man his D.E.W.”). Williams’s influence on the business was now so significant that every bottle bore his imprint.

Daniel Williams expanded the Tullamore site and brought in electricity long before its use was widespread across the country. He introduced motor vehicles and ensured the company made use of the new Grand Canal, which would eventually link Dublin with the River Shannon by way of Tullamore. The canal brought in the coal to power the stills, and took away shipments of whiskey for distribution. When Ireland’s railway system reached the town, Williams saw to it that the distillery had its own siding.

Under Williams the business prospered, but by the time he died in 1921, Tullamore was about to enter the prolonged decline suffered by most of the Irish distilling industry in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1954 the distillery ceased production. In the mid-1960s the Williams family married into another great Irish distilling dynasty, the Powers family, with the wedding in Dublin of Teresa Williams to Frank O’Reilly, great-grandson of John Power.

The Tullamore brand became part of Irish Distillers, with production of whiskey shifting from John’s Lane in Dublin to Midleton in County Cork. The name was bought by the C&C group in 1994, then sold again, in 2010, to William Grant & Sons, who decided to build a new distillery back where it all began, in Tullamore—returning distilling to the site for the first time in over sixty years.

The symbol of the distillery, a phoenix rising, was seen once again. Production started in 2014—following the same methods as always. Before new-make spirit started to flow in Tullamore, grain and pot still whiskey were sourced at Midleton, with malt produced at Bushmills. All production is now fully grain-to-glass and in-house. There are four mighty warehouses, each holding fifty-five thousand casks.

The old bonded warehouse on-site houses a state-of-the-art visitor center that takes you through not just how Tullamore D.E.W. is made but the remarkable history of the distillery and many of its characters. There are three levels of experience available, from the general introductory to a whiskey master class up to the ultimate, which lasts for almost five hours and includes a behind-the-scenes tour, tasting, lunch, and even a chance to create your own blend.

Today, Tullamore D.E.W. is the second-largest-selling Irish whiskey in the world (after Jameson). The style is distinctive, even unique. The range has been extended in recent years to include numerous reserve releases and some experimental cask finishes. Although the relative newness of the distillery places Tullamore in the category of the second wave of Irish whiskey-makers, in truth, it belongs to the great tradition. The address may have changed a couple of times, but Tullamore D.E.W. is finally home again and home to stay. Which, in this triple-obsessed setting, leaves only one more thing to add: three cheers.

first distillation

2014

stills

6 Pot Stills (Pot Wash Still: 21,000L,

Malt Wash Still: 16,000L, Two Intermediate Stills: 11,000L, Two Spirit Stills 11,000L)

3 Column Stills

lpa

12.8 million

whiskey styles

Single Malt, Pot Still & Grain

VISITOR CENTER/TOURS

Yes

The Tullamore range now includes single malt and blended whiskeys–all triple-distilled, 0f course.

tullamore d.e.w. original

ABV: 40%

12-year-old special reserve

ABV: 40%

15-year-old trilogy

ABV: 40%

old bonded warehouse release

ABV:46%

cider cask finish

ABV: 40%

xo rum cask finish

ABV: 43%

single malt 14-year-old

ABV: 41.3%

single malt 18-year-old

ABV: 41.3%

The secret room where they grow the stills . . .

Three column stills, which also constitute Tullamore town’s only skyscraper.

Looks peaceful, doesn’t it? And it is.

Bernard Walsh is a great man for the details. Details such as finding the perfect location for your distillery. Understanding the processes that favor the skilled hand of the maker rather than the mind of the machine. Creating a visitor experience for the casual visitor as well the serious aficionado. Bernard is surrounded by such details in Royal Oak, here in the heart of the heart of barley country.

The distillery, the first to be opened in Carlow in over two hundred years, is today one of the largest independent producers in Ireland, employing around a dozen distillers alone. It’s also the first Irish distillery to produce all three core styles of Irish whiskey in the same stillhouse—pot still, malt, and grain. Many of the processes continue to be done by hand, in the traditional nineteenth-century style. Because, Bernard believes, this allows the distiller greater control, especially when making small batches or special runs. The water source is a local aquifer, some seventy feet beneath the fields. All of the distillery’s barley is Irish.

Walsh produces two whiskey brands, both triple-distilled, both quite exclusive. The Irishman is traditional in style, a 70/30 blend of single malt and single pot still. When it was launched, it was the only Irish blend containing 100 percent copper pot still distillates and 0 percent grain or column still whiskey. Writers’ Tears is a more modern take on traditional Irish whiskey, in a 60/40 blend of single malt and pot still. Both ranges have won numerous awards worldwide.

Bernard’s journey into whiskey began when his enterprising wife, Rosemary, created a ready-made Irish Coffee drink (the cheekily named Hot Irishman). The product took off, and Bernard undertook to source whiskey to keep up with demand. A task became an interest, which became a passion and eventually a desire to distill his own whiskey.

The focus of the business isn’t volume; it’s quality—first and last. “We’re not looking over our shoulders,” says Bernard. “We’re looking down the road. And we feel we’re just getting going.” He believes that the same outlook can be applied to Irish whiskey in general. The industry is, he thinks, at a juncture. And the future will belong neither to heritage nor innovation alone but to quality.

In addition to driving ahead the continued development of the distillery, Bernard Walsh is restoring Holloden House, a Georgian mansion on the Royal Oak estate dating from 1755. He is doing it slowly, brick by numbered brick. That’s attention to detail. That’s the Walsh way.

FIRST DISTILLATION

2016

STILLS

3 Pot stills (Wash Still: 15,000L,

Intermediate Still: 7,500L, Spirit Still: 10,000L)

2 Column Stills

LPA

2.5 million

whiskey STYLES

Single Malt, Pot Still & Grain

visitor center/tours

Yes

The irishman founder’s reserve

ABV: 40%

The irishman 12-year-old single malt

ABV: 43%

The irishman 17-year-old

ABV: 56%

WRITERS’ TEARS RANGE:

COPPER POT

ABV: 40%

RED HEAD

ABV: 46%

CASK STRENGTH

ABV: 53%

Bernard Walsh talking details.

A family of pot stills in their native Carlow habitat.

Making the cut: the spirit safe in use.

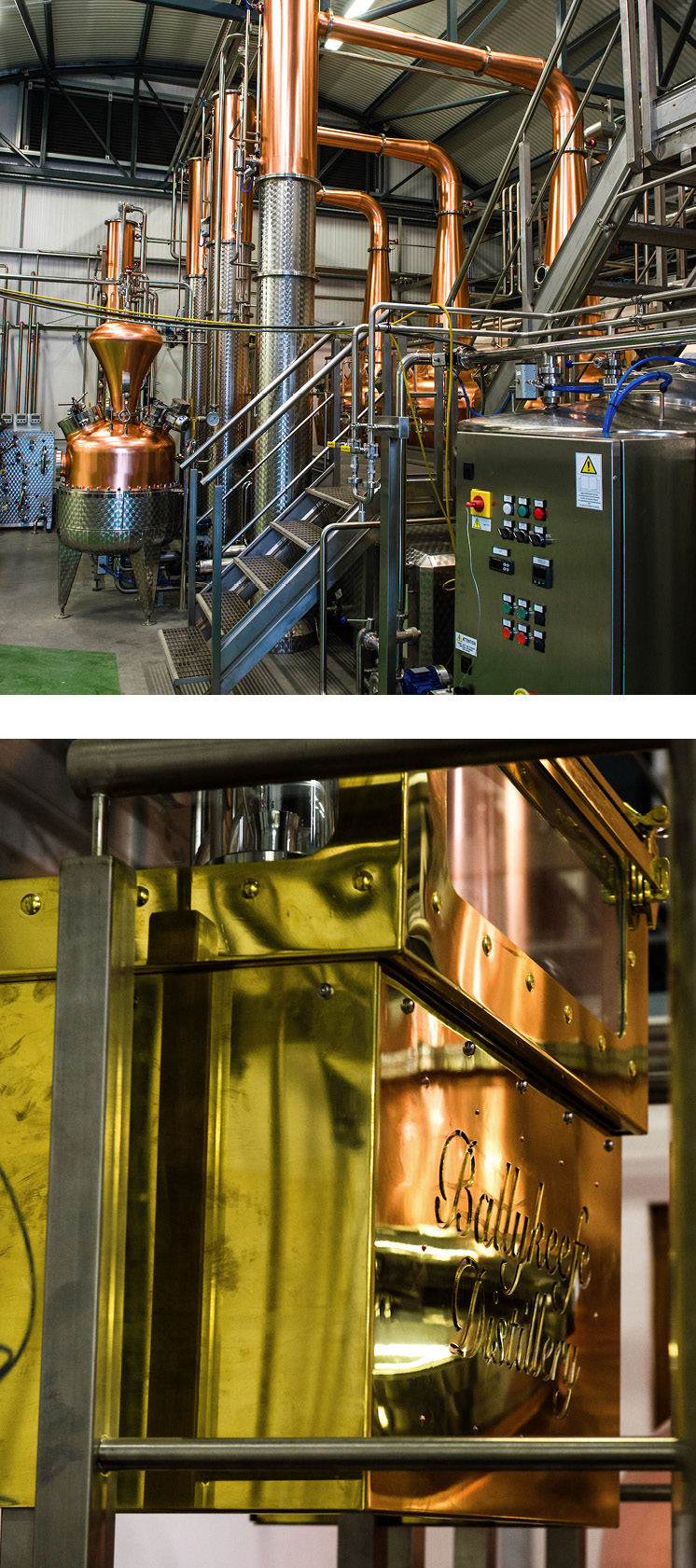

Bravissimo! The first Italian Barison stills installed in Ireland.

Farmers are a resourceful, resilient lot. Where obstacles exist, they find a way around them. Where no opportunities exist, sometimes they create them.

Take Morgan Ging, a farmer among generations of farmers who have worked this land as far back as records go. His farm in Kilkenny is divided between rearing beef cattle and cultivation for barley. Morgan’s also always had an interest in distilling. Could that and his knowledge of barley production be brought together in a way that would create a new opportunity for the farm? Of course they could.

Once Morgan had secured a spirit-manufacturing license, work could start in earnest. He identified a site—a large, old cowshed he wasn’t using anymore, but it was in the wrong place. The solution was obvious: Dismantle it stone by stone and rebuild it in the right spot. See? Resourceful. Morgan adds an interesting footnote to this. A local man who looked after the unmaking and remaking of the cowshed turned out to be the grandson of the original builder.

In a very real sense, that little anecdote represents a core principle of Ballykeefe: Everything about it is local. The grain and the water come from the farm. All the spirit will be distilled here—no third-party new-make or sourced whiskey will be needed. The pot ale and spent grain will go back to the land or passed on for local animal feed. The entire distilling circle—sowing the barley, harvesting it, storing it; malting, distilling, maturing, and bottling the spirit—will all take place here. The grain-to-glass mantra is not a goal at Ballykeefe; it’s fact. Sustainability is a prime concern here. There is a heat recovery system, rainwater harvesting, water recycling—all part of a commitment, no,

an obligation, to the land: to pass it on in a better state.

At the time of our visit, the distillery was not yet producing whiskey, though it is making and exporting some very impressive gins and vodkas. Since production capacity is limited, every bottle can be individually numbered. As master distiller Jamie Baggott says, “Limited edition is the only edition here.”

Where the whiskey-making is concerned, they are taking their time with the setup. “It’s practically impossible to retrofit in a distillery,” Jamie says. “There’s only one way to do it and that’s to do it right from the start.”

Ballykeefe’s own new-make is triple-distilled pot still whiskey. In addition to using their own barley, they are experimenting with rye, which is quite unusual in Irish distilling.

For the master distiller, however, nothing is off-limits. “There are no boundaries in what I will play with,” Jamie laughs. (And he certainly has an enviable reputation for experimentation, especially with gins.)

For a self-described family farm with an artisan distillery, this is no small undertaking. The equipment is first-rate and the investment has clearly been substantial. The stills are by renowned Italian specialists Barison, and are their first installed in Ireland, as a showcase for their expertise and workmanship.

Visitor tours take you through each stage of the brewing and distilling process, from milling all the way to the warehouse and bottling plant. The tasting room—a reclaimed stable block—has been styled as a comfortable and welcoming Irish country lounge, with an impressive oak bar counter.

Kilkenny was the medieval capital of Ireland. It also claims to be the place where uisce beatha was first distilled. Certainly the name appears in the earliest extant written records, which are dated to 1324, and a text known as the Red Book of Ossory. There was a long history of distilling in the area that faded away, as was the case with most regional spirit-making. Ballykeefe is the first new distillery here in over two hundred years. Ecologically sound, sustainable, and quality-focused, it marks a welcome return.

first distillation

2017

STILLS

3 Pot Stills (Each: 1,800L)

LPA

Less than 100,000

Whiskey styles

Single Malt & Pot Still

VISITOR CENTER/TOURS

Yes

BALLYKEEFE IRISH WHISKEY

Ballykeefe founder Morgan Ging, center.

Open sesame—but mind your step.

The lettering on the immaculately painted facade may read “P. Bermingham,” but most people around here still call it “Marmion’s,” after Michael Marmion, the hugely popular and charismatic late owner.

7 Ludlow Street

Navan

County Meath

This is the oldest pub in Navan. It’s also tiny. Seriously tiny. With just twenty people in, it’s packed. Even so, Michael Marmion always made sure there was room by the fire for musicians.

It’s the kind of pub made for conviviality and craic, rather than solitary reflection. As Lorraine, Michael’s partner says, “People talk to each other in here—there’s always a great atmosphere.”

The pub has been in the same family since 1884, when it was bought by a young Patrick Bermingham and his sister Jane. Back then it was a standard Irish spirit grocer—food and dry goods counter on one side, pub on the other. Patrick died suddenly, not long after buying the pub, and Jane continued to run the place on her own for the next sixty years. She never married but did adopt a five-year-old cousin, John Marmion. He inherited the bar in 1948 and in due course passed it on to his son, the aforementioned Michael.

The building hasn’t changed much at all since Michael took it over. Even when he gave up the grocery side—which was only in the 1980s—he reused the old counter and shelving. So practically everything you see here is original. There are some quirks around the place, like the copper-colored ventilation system snaking across the ceiling, the collection of ceramic whiskey jars, and the weathervane topped by a leaping horse. Then there are the elaborate wrought-iron roses garlanding the opening to the snug.

When Michael died, his wake was held, naturally, in his pub. On the day of the funeral, the town came to a standstill. People gathered outside Bermingham’s and sang many of the songs he loved—a measure of the affection in which he was held, and of the importance of the pub itself to its many regulars.

There’s no TV here, no food, no Wi-Fi; but there is live music four nights a week. There’s also a very impressive whiskey selection—including some rarities—and an equally impressive range of gins and rums. You’ll of course get a fine pint here, and you know what that means. You’ll soon be wanting another.

Have a seat. With any luck, this is going to take some time.

The Hill of Skryne faces the Hill of Tara, home of the ancient High Kings of legend. So this is ancient, mythical Ireland you’re in. It’s therefore to be expected that time seems to run a little differently.

The Green

Skryne

County Meath

However, there is a schedule: The cows pass by, twice a day, as they always have. And at four o’clock, O’Connell’s opens its doors.

When the teetotal Mary O’Connell first came here with her new husband, James, in the 1940s, the business they took over was a thriving spirit grocer, selling everything from animal feed and bicycle tires to sausages and jam—as well as whiskey and bottles of stout. There are still traces of the grocery side around the place, but the pub’s the main thing. It’s quintessentially local. Step in and you’ll overhear earnest discussions about cattle prices and land and always, always GAA—last weekend’s results and next weekend’s fixtures. Around the walls are newspaper clippings of sporting success, postcards from the homesick, photographs of horses, a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s “If,” and community notices. You’ll see an open fire, a long bench facing the bar, and a creamy paneled ceiling. In the back room, which has something of the air of an old-fashioned tea shop, there’s a piano. That’s the entertainment center. There’s no food, TV, or radio, let alone Wi-Fi. As far as the drinks go, the offering is simple, classic: Guinness and a couple of draft beers; a handful of whiskeys, gins, and other spirits. That’s about it. Anything else would be superfluous to the character of the place.

O’Connell’s—widely known as “Mrs. O’s” after the woman who continued to run the pub until she was in her nineties—has been here since around 1870. It may in fact be longer; no one’s really sure or, frankly, that concerned. It’s been featured in many movies and commercials and photo shoots because it’s so utterly authentic and atmospheric. There’s nothing pampered about O’Connell’s. It is worn and warm; functional and plain; a little bit rickety here and there; and quietly, timelessly magnificent.

So if you ever find yourself in the realm of the High Kings, pay your respects to Irish hospitality here at the shrine of Skryne.

Earnest discussions about cattle prices and land . . .

Rush hour in Skryne. Best just to wait it out in Mrs O’s.

Here’s a thought. Right at the very center of Ireland is the town of Athlone. The town grew out of a settlement, which grew up around an old inn. So you could say that at the very heart of Ireland is a pub—this pub.

It’s been here, trading continually, since A.D. 900. That makes Sean’s Bar officially the oldest in Ireland, and possibly the world.

The original inn was created at the ford of the mighty River Shannon by a man called Luain, who helped people cross and, presumably, also provided sustenance for the weary traveler. While doing work on the bar in the 1970s, the owners found that some of the old walls were made of wattle and wicker—ancient interlaced twigs and branches bound together with dried mud. And in those walls they also discovered tokens or coins dating back to the tenth century and the inn’s original owner.

Amazingly, the bar holds detailed records of every owner since Luain—and of course the original Sean, a local cattle dealer who bought the place in the 1950s. (A story that Boy George bought the place in 1987 was in fact an April Fools’ joke that’s still going around.)

The River Shannon has featured prominently in the life of the bar, with many pictures and memorabilia such as antique fishing rods, oars, and driftwood around the place. It’s also the explanation for the bar’s sloping floor. Long ago, whenever the river would rise and burst its banks, flooding the bar, they just opened the door and let the waters run out. How practical. (The flooding problem’s been taken care of, but that’s no reason to get rid of a perfectly good, if somewhat sloping floor now, is it?)

Sean’s is also the only pub in Ireland where you are allowed to pull your own pint of Guinness—under supervision, of course. Unusually, they also have their own brand of stout and even a Sean’s Bar Irish Whiskey. Gin aficionados and Irish Coffee devotees are well catered for here, as well. In regard to food, there is none served in the bar, although a proper restaurant is being built in the back.

There’s music every evening and a blazing turf fire in the winter. Boy George doesn’t know what he’s missing.

Welcome to the pub at the center of the (Irish) universe.

At a time when women weren’t much welcome in Irish pubs, the first of three generations from the same family was running this one.

Main Street

Ballitore

County Kildare

The “E” in E. Butterfield stands for Elizabeth. Today, her granddaughter Lisa Fennin stands behind the bar in the tiny, one-room pub she grew up in, and which she took over from her mother, Philomena. Philomena worked here every day for nearly fifty years. When she died, Lisa held the wake here, in her mother’s pub.

Despite the name over the door, the place has always been known as “The Harp,” in reference to the sign above the faded “E. Butterfield” lettering. The symbol is significant, for there is history everywhere here in this little village far off the usual tourist path. Some of it is glorious, some tragic, and all of it vividly remembered and endlessly debated, as much of Ireland’s history tends to be.

Like so many traditional rural pubs, this also was once the local shop, and the old wooden grocery drawers are still in place. The shelves are lined with strange bric-a-brac and memorabilia advertising long-vanished products. The building dates back to 1770 and has been a pub since 1780. The farmyard doors, vast open fireplace, ancient counter, and whitewashed walls look like they’ve been here since then, as does the almost comically uneven flagstone floor. “You’re all right coming in,” the locals say, “but you have to watch yourself going out.” The seats include former church benches and an assortment of stools and chairs randomly distributed about the room. Somehow, it all makes perfect sense.

Lisa, like her mother and grandmother before her, is very fussy about her pints. So you can expect a good one here—a very good one. The whiskey selection is short on choice and long on tradition—the classic triumvirate of Jameson, Paddy, and Powers. No, they don’t do food; and no, there’s no Wi-Fi. There is a TV, though it doesn’t get a lot of use. “People come in for the chat,” says Lisa. “I think having the TV on would spoil that, don’t you?”

Butterfield’s has a large open fire, which is lit almost every day. If it’s the first Friday of the month, there’ll be a proper seisiún happening around the hearth. And even if it isn’t the first Friday, well, there still might be one. It’s that kind of place. Butterfield’s is not really a pub for a swift drink. It’s not built for life in the fast lane. So, if you get a chance to visit, be prepared to take your time. You’ll get where you’re going eventually. In the meantime, just settle in and make yourself comfortable. There now, that’s better.

Now, the floor does have just the teeniest, tiniest irregularity . . .

Stephen O’Brien was a sickly man. His doctor counseled fresh country air, so in 1880 Stephen sold his tea shop in Dublin, moved to Athy, met a local woman, and bought a spirit grocer.

Evidently, as his granddaughter Judith wryly observes, “The local air clearly did him a power of good, as he went on to father eleven children.” And in addition to founding a dynasty, he left a fine pub legacy.

O’Brien’s is an essential part of the town. Everybody knows it; everyone has been in it. That’s because, unusually for pubs that began as spirit grocers, this one still operates both parts equally—grocery store and bar. There’s a long, single counter that runs the length of the place, intersected by a partition and doorway into the tiny bar in the back.

The pub is usually called “Frank’s,” after Judith’s father, who ran the place for decades. It’s said that he was the town’s greatest champion and enthusiast. A onetime mayor of Athy, he used the shopwindow of O’Brien’s to announce every event, celebrate sporting success, promote every occasion involving the town. That community spirit still imbues the bar today. It’s a meeting place, a focal point, and a talking shop.

There are shelves and shelves of books behind the bar. But they’re not for decoration. “They’re our pre-Google technology,” laughs Judith. “They’re consulted all the time by regulars. If there’s some burning issue being disputed—say about who won the 1927 intermediate county hurling final—we can settle it quickly.” The collection is added to all the time. Whenever anyone local writes a book, which is surprisingly often, a copy is ceremoniously added to the O’Brien’s Library of Reference.

The outside of the pub hasn’t changed in about 140 years. (Look closely and you can still see the rings once used for tethering horses.) The signage is in Irish, and if you do happen to have cúpla focal—a couple of words in the mother tongue—feel free to give them an airing here. (There’s a sign in the shop that reads Tír gan teanga, tír gan dúchas—“a country without a language is a country without a birthright,” so they do take the matter seriously here.)

Like several of the owners we’ve featured here, Judith has a strong sense of responsibility toward her bar. Yes, it’s her family’s legacy, but the pub is also an expression of Irish culture. “The work is hard,” she says, “but it’s worth doing. It matters.” That’s a noble sentiment, if ever we heard one.

Grocery in the front, pub in the back: a very practical arrangement.

In days not so long gone by, if you were in Abbeyleix and looking for a grocer’s shop, or an auctioneer, a bakery, an undertaker, a carpenter, or travel agent, there’s only one place you’d have gone: this place.

Main Street

Knocknamoe, Abbeyleix

County Laois

Back then, a pub was the center not just of social life in a town or village but also of commercial life. Today, in Morrissey’s there are glorious traces of all its many pasts displayed here in its present—in cabinets and on every shelf and in every nook. There are old scales and measuring equipment here and there among the drawers and ledgers. There’s even a branded delivery boy’s bike up on a high shelf. (Thankfully, the old hearse that was kept in the yard along with the stockpile of coffins is long gone.)

Built back in 1775—and a shebeen before that—this pub is composed almost entirely of character, from its uneven stone floor right up to its dark-red ceiling. Things in general are a bit aslant and askew. But what’s so good about right angles anyway? Current owner Tom Lennon was besotted the instant he set eyes on the place years ago. He still is. The previous owner had cared for the pub for over fifty years and not changed a thing. Tom sees no great need to either. “It’s as nice a pub as you could have,” he says modestly, “so why change it?” It’s a fair question. “We have turf burning in the old potbellied stove there—and you can’t get more organic and modern than that,” he adds with a grin. All the fixtures and fittings are original, as are Tom’s strong opinions on pubs. “There’s a lot of nonsense talked in a place like this. And that’s the way it should be. A place like this is an escape from reality. We sorely need that in the world today.”

Admittedly, there is a TV in the pub, but it’s only used to screen the odd GAA or rugby match. Which then prompts even more conversation. Morrissey’s does serve food—good-quality pub grub—and, as you’d expect, serves a fine pint. The drink selection in general is perfectly adequate, and is just what the clientele want. (So if you’re in the mood for a mojito, this isn’t your best bet.)

Some people have said of Morrissey’s that it’s caught in a time warp. Tom Lennon doesn’t view that as an insult at all. His pub is actually listed as an officially preserved and protected building, both inside and out, which means that changing anything is difficult. Very difficult. With a bit of luck, maybe even impossible.

Tom Lennon, a man in love with a pub.

Note the distinctive long, curved bar.

You’ve heard the old saying “Come for the craic. Stay for a pint. Leave with a light bulb.” No? Well, maybe that’s just because you haven’t been to O’Shea’s.

Main Street

Borris

County Carlow

several of the pubs in this book began as spirit grocers. O’Shea’s is one of the very few that has kept the grocery side going, albeit in a reduced fashion. But in a town of really only one street, it’s just the practical thing to do.

Michael “Bossman” O’Shea bought the business in 1934 and built it up to a thriving store dealing in, well, everything from wool, coal, and grain to farm supplies. Today his grandson, also Michael, runs it, along with his sister, Olivia, and mother, Carmel. They’re mindful of the tradition they’ve been entrusted with, and strive to maintain those old standards of hospitality.

The counter predates Bossman’s purchase. It’s probably 120 years old, and the dark wood is polished to a glossy, glassy sheen by generations of happy elbows. In fact, much of the bar remains unchanged. The original bacon slicer is still there. A room was added in the back at some point. Oh, and new stools arrived a year or ten ago, someone remembers, vaguely. The candy-striped bar front is unusual, but then there’s also a single Wellington boot hanging from the ceiling. So who’s to say what’s usual?

Sometimes there’s music, sometimes there isn’t. But there’s always a fire and a friendly greeting. It’s a Guinness pub, of course, which doesn’t just mean that they serve it here (all pubs do) but that O’Shea’s is known for the exceptional quality of its pint. For many an Irish pub-goer this is the ultimate imprimatur. There are some craft beers on offer, too, along with a decent whiskey selection, and a fair few gins. There are no cocktails (“A G&T is as fancy as we get,” says Michael). O’Shea’s does offer some basic but good pub grub at lunchtime—sandwiches, soups, etc. But people don’t really come here for the food. They come because it’s a wonderful, uplifting place to spend an hour or two in good company of an evening. And then maybe pick up a box of nails, some fishing line—oh and, yes, a light bulb—on their way home.

O’Shea’s: ready for life’s essentials and, more importantly, its nonessentials.

In Lenehan’s you’ll hear people talking about “The Cats” at all hours. For the uninformed, this isn’t some local feline obsession. It’s a hurling obsession.

10 Castlecomer Road

Kilkenny

County Kilkenny

The mighty county team is nicknamed “The Cats” after an old phrase, “to fight like a Kilkenny cat,” meaning to be fierce, tenacious, and determined.

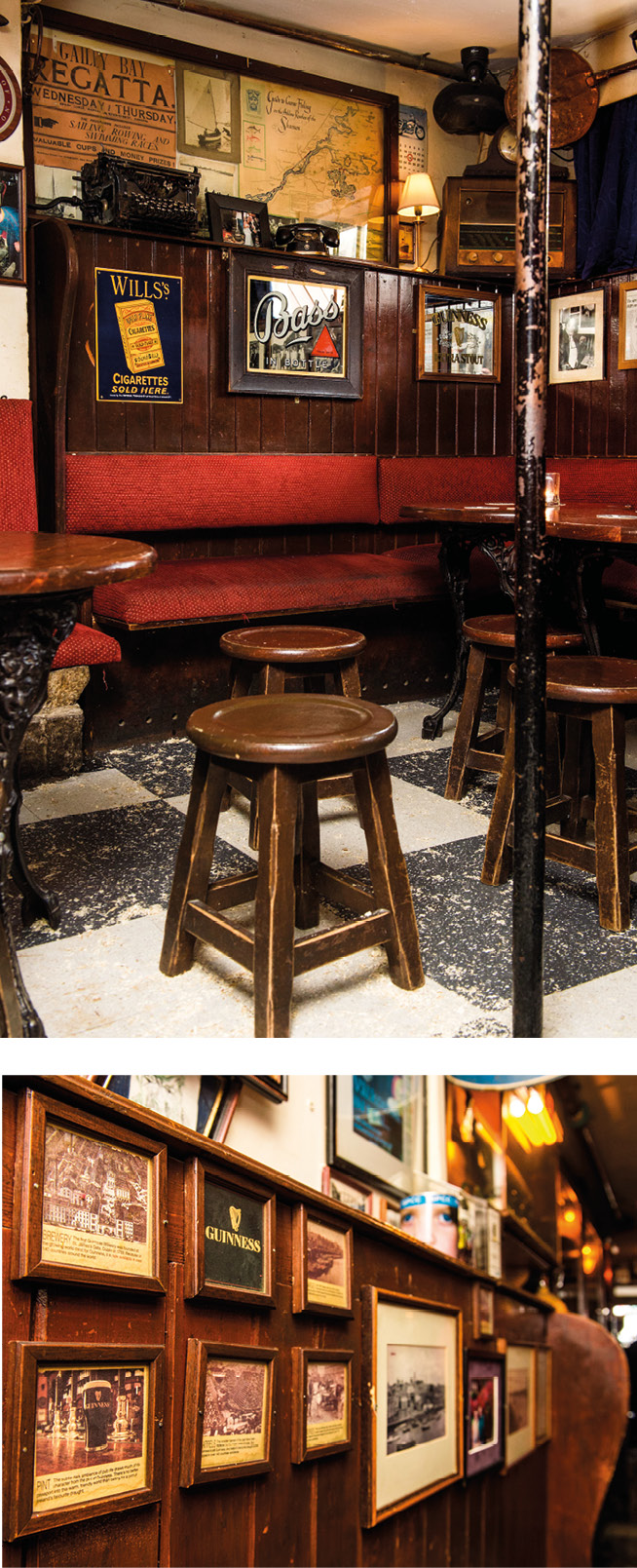

There’s lots of Cats memorabilia in here, with the county’s black and amber colors hung in bunting above the bar. Of course, there’s lots of other stuff, too—old mirrors and advertising signs, ledgers and bills from the bar’s former spirit grocer days, ceramic pots, even some old typewriters. You know, the usual bewilderment of curios and ephemera.

Apparently the counter has a slope. They say that when it starts to appear level, it’s time to go home. However, most people tend to ignore that advice and stay as long as they possibly can. Because it’s lovely in here. Better than that, it’s wonderful.

The pub is on a busy corner and is surrounded by the noise and bustle of the modern world. But inside, things are very different. It’s timeless, a gem of a traditional rural pub that’s somehow been marooned in the city, like a pearl hidden in an oyster.

Predictably, that other great black and amber pairing—Guinness and whiskey—is well respected here. There’s also a good selection of gins and some craft beers. Food-wise, there’s fresh soup and sandwiches available at lunchtime, and that’s about it.

The Lenehans have had this pub since around 1890, but the family has been in the local booze business since the early 1700s. So they know a thing or two about hospitality. They have a gently persistent determination to make you feel comfortable. In that regard, they’re a tenacious lot, the Lenehans, a bit like the Cats themselves.

So find yourself a seat, order a drink, and don’t worry about the look of that counter. It’s perfectly flat. It’s the world that’s tilted.

Welcome to a magical Kilkenny oasis.

A gem of a traditional rural pub that’s somehow been marooned in the city . . .