Not all teamsters have the time, money, or desire to start training oxen as calves. Although cattle are easier to train as calves, adult cattle also have the capacity to learn to work in a yoke. Starting an animal’s training when he is closer to maturity requires a more advanced level of skills and techniques than would be needed by a teamster working with calves.

Waiting until cattle are mature to begin their training has both advantages and disadvantages.

Some of the advantages include:

Disadvantages include:

Cattle with long flight distances, showing an obvious fear of humans, may need a period of acclimation and mild restraint before being handled. This period varies from animal to animal, but may be days or weeks. Your initial objective is four-fold:

Place the animals in a corral or barn where all their feed and water are provided. Make sure they cannot escape, which would allow them to realize some dominance and independence. If you are training a single animal, pen him alone; if you are training a team, pen the teammates together. Do not corral the animals with a larger group, or they may not associate their captivity with humans.

Make your initial contact with them as pleasant as possible. Do not beat or push aggressive cattle into submission; doing so only reinforces their fear of humans. Being enclosed is stressful to animals that are used to freedom. Do not continue training until they seem at ease with their surroundings.

When properly trained and matched with the right teammate, a wild and aggressive steer may turn out to be the best animal in the yoke. Beware of animals that represent either extreme in temperament. Cattle that are extremely aggressive or extremely shy will never make good work animals.

Once the cattle have been acclimated to being near people, use adequate equipment and appropriate methods to capture and restrain them. Time spent preparing a corral, ropes, and hitching posts to withstand the most unruly animal will pay great dividends. The worst thing that could happen during an initial capture is to have an animal break loose or realize his superior strength. Cattle that fear humans quickly learn how to escape.

The best method of restraint is one that is fast, effective, and safe. Capture in the United States usually involves the use of a corral, a chute, and a locking headgate. The animals are caught in the corral, moved through the chute and individually captured in the headgate. They may then be restrained by halters, ropes, or nose rings and tied to be allowed to fight their restraint. Cattle that have been properly acclimated to people and their new surroundings will not fight for long.

Never leave a green animal tied and unattended. He may choke, suffocate, or get tangled in the ropes. The most effective way to train cattle is to keep them restrained in close quarters after the initial capture. Cattle in the northeastern United States are usually kept in a barn until they can be handled and touched, and no longer resist being tied.

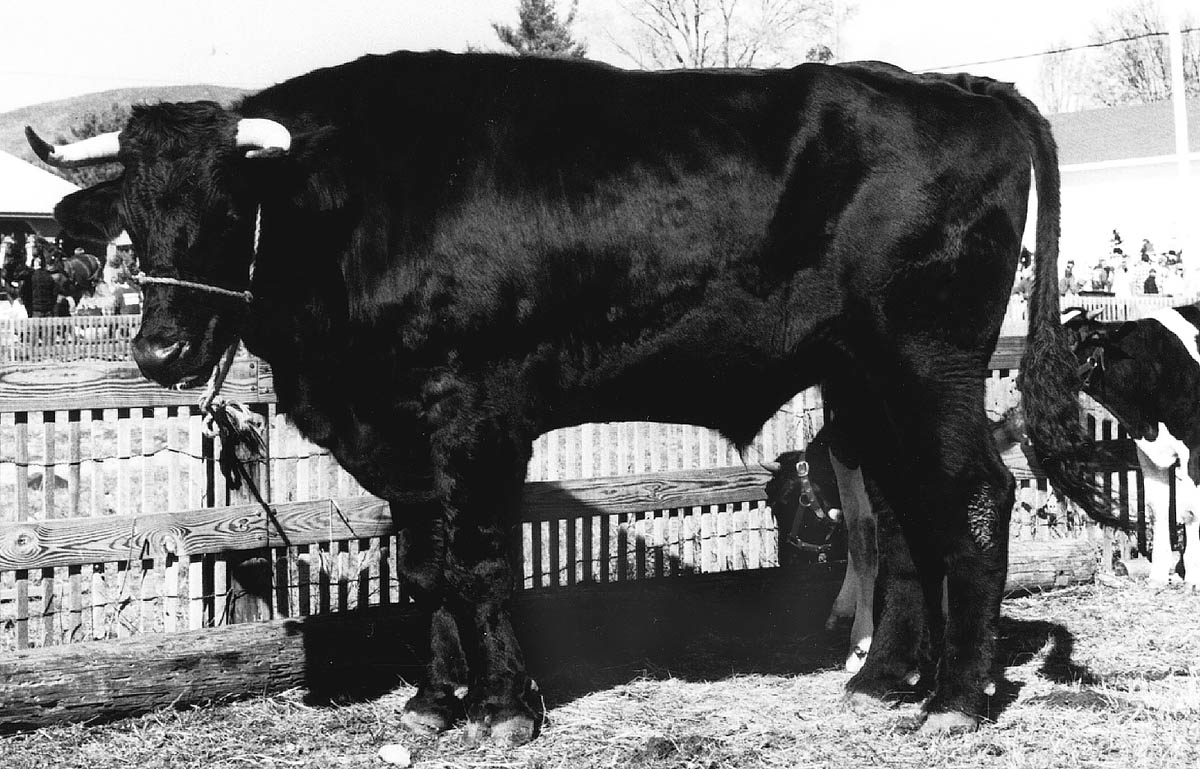

Cattle weighing in excess of 3,000 pounds may be haltered, led, and handled only because they believe humans to be dominant; if this ox just once learns he can break the halter, no normal halter or rope will hold him in the future.

Many teamsters believe that it’s best to start animals individually on a halter before yoking them as a team. Halter training allows the teamster to work with and evaluate each animal and allows each animal to become accustomed to being handled.

Some teamsters, on the other hand, feel that a more effective technique is to work the animals in a training ring without a halter before yoking them for the first time. Training in a ring has the distinct disadvantage that the oxen learn to associate only the ring with being in the yoke and responding to the teamster. Their first few sessions outside the ring will be challenging and will require a lead rope.

Still other teamsters begin training by tying a green animal to a trained animal. In Africa, and historically in parts of the United States, some ox teamsters turn the tied-together animals loose to learn to get along and walk together.

However, real training begins after the animals realize that they have to respond to humans. This often begins by learning to respect a tug on the rope they are tied with. Each animal as an individual must learn to respect a halter and lead rope.

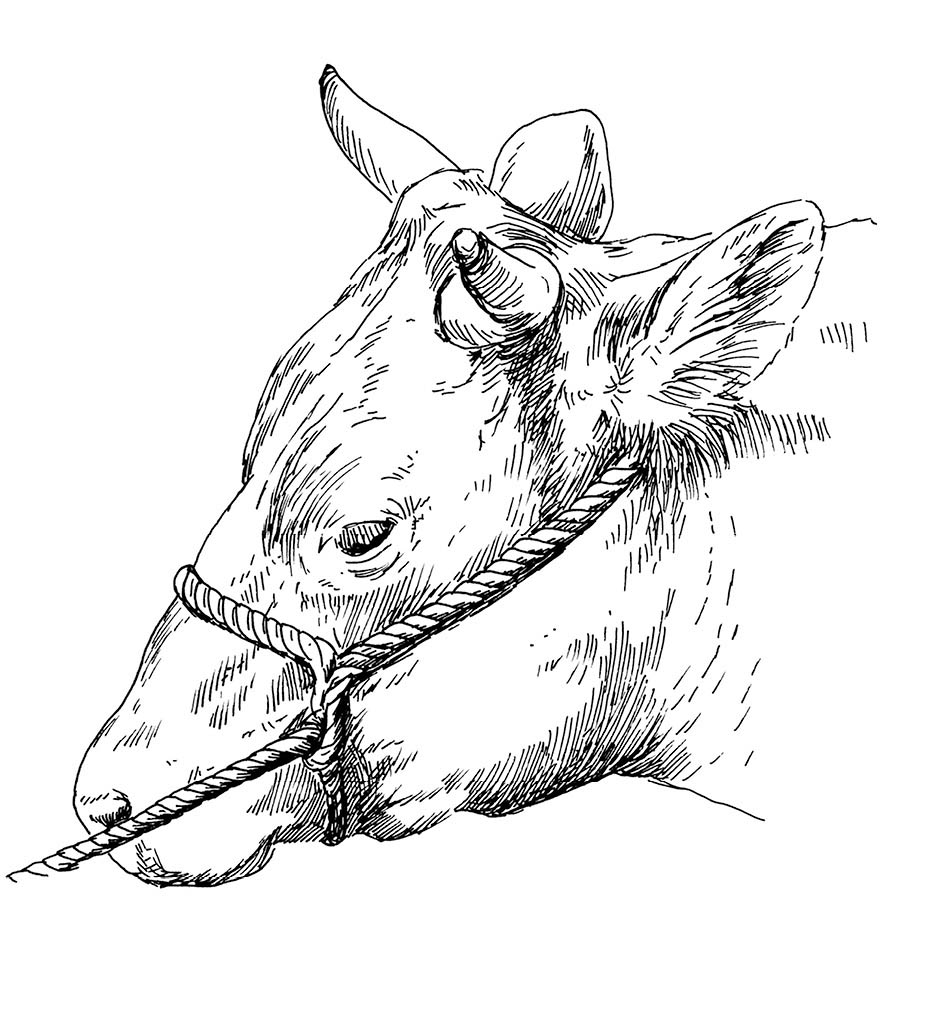

A sturdy rope halter, which applies pressure to the nose when drawn tight and releases when the animal gives in, is strong enough to hold an older calf or young steer.

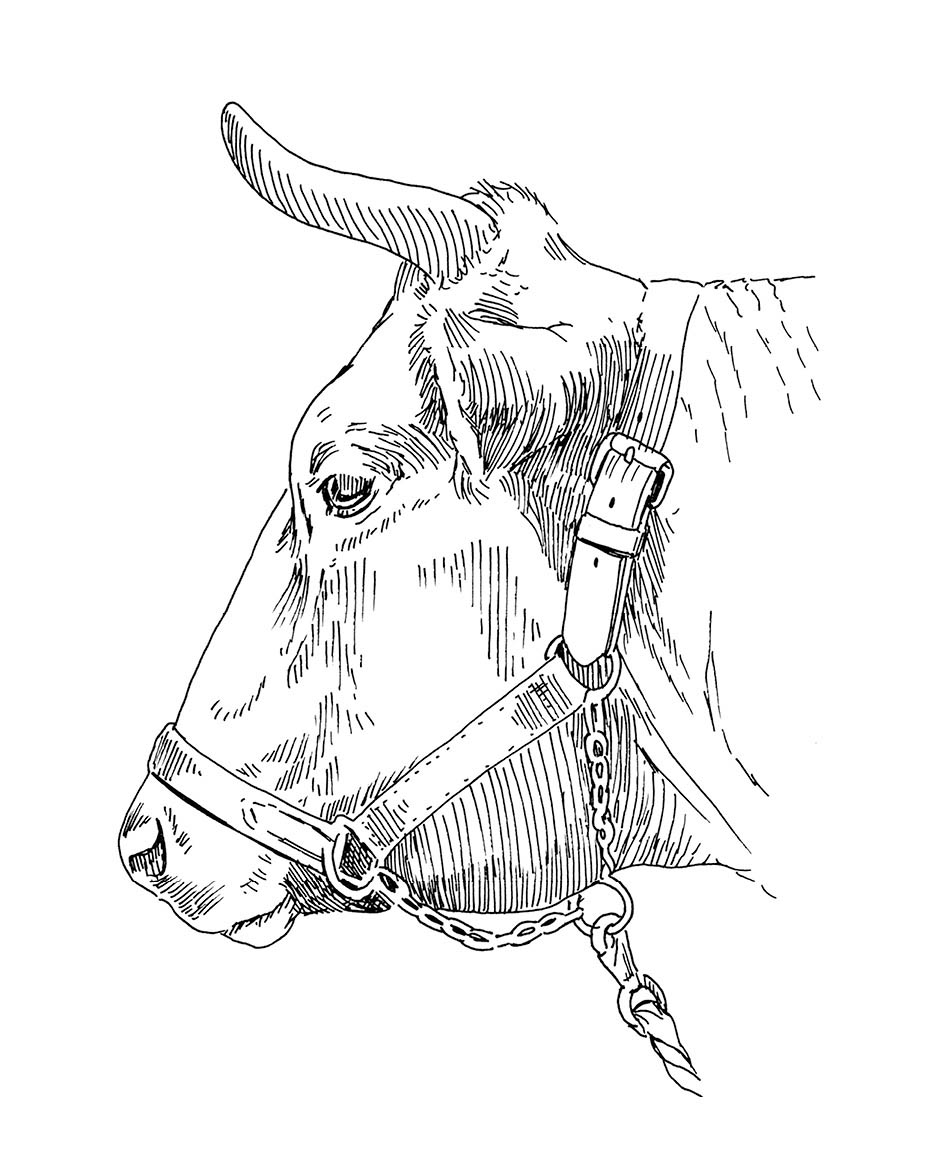

A stitched nylon halter offers a rugged alternative to leather, but is not suitable for halter-training older animals if it lacks the option of tightening on the muzzle when the animal does not respond.

A heavy multilayered leather halter has chains that draw tight if the animal pulls or resists. Such a halter is appropriate for a larger animal that has learned to break a less sturdy halter.

Hitching the ox by his horns saves money, as no halter is needed, but it gives the animal so much power that the trainer will have no leverage in holding him.

Too much whip in the face or on the nose early in training causes cattle to toss their heads and become head-shy.

Initial training on a halter should include the commands to start and to stop. Make sure your physical, verbal, and visual cues are all consistent and easily understood. When you say “get up,” say it the same way each time and follow with the whip going up in the air. Touch the animals on their rumps to get them to go forward.

Most teamsters stand on the left side of their animals rather than in front of them. This position aids in getting the team to move forward. Standing to the left side may become a cue for them to move forward or pay attention, but they should not move forward until they are commanded to do so.

To teach the command to stop or whoa, say the command and follow it by bringing the whip down in front of the animals and touching them on the noses or knees. You have given verbal, visual, and physical cues. Some teamsters also stop walking; the team quickly learns to stop when the teamster stops. Teaching your team to expect this additional cue may be undesirable if you hope to eventually drive from behind.

Don Collins, a veterinarian and accomplished teamster from Berwick, Maine, has stated:

“Training a team of calves involves first teaching the animals to function in the yoke, and later teaching them to work on the cart or drag. But starting with an older team, it may be easier to hitch them to a load, teaching them to pull at the same time you’re teaching them to work in the yoke. [The weight pulled by the team becomes a system of restraint.]”

Animals that have been captured, restrained, and not allowed to escape during halter training have learned that you can dominate them. While this method of teaching dominance may not be the swiftest, it rarely causes animals to lose their spirit. In other parts of the world harsh training often results in animals that learn to lie down in the yoke.

Some methods of exercising dominance are so severe that the team becomes lethargic when placed in the yoke. Lying down on the job is not the desired result of dominance training. Harsh methods of restraint — such as the “running W” (see Glossary), roping a foot, or beating an animal severely — often have the opposite of the desired effect. Instead of motivating the animal, these techniques teach him to lie down in order to resist being trained.

When the team is first taken out of the corral, they should continue wearing halters until they learn to respond in the yoke.

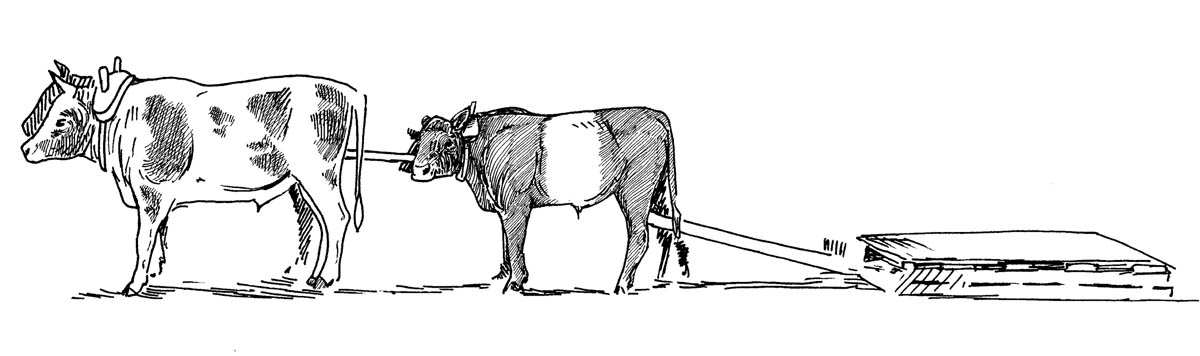

A training system that encourages rather than discourages the animals is to use an experienced team ahead of green animals, with a light load behind them and a pole between. If the animals are too wild or unruly to hitch, or no other team is available, physical restraint such as the running W or other rope system may be warranted, but these methods are extremely severe. I prefer to hitch the animals and allow them to pull a load to tire themselves out. Once tired, they are more likely to pay attention.

A green pair of young Dutch Belted steers hitched between a larger team of Holsteins and a sled, the sled’s pole serving as a training aid. This system initially keeps the green animals under control, but they must eventually learn to work as a pair, without another team ahead of them.

Some teamsters hitch the green team to a load, in a fenced corral or pasture, and fight the steers until they obey the commands to start and stop. This system is referred to as the “cowboy style.” Even if you are using the cowboy style, have a goal and work toward it. Be sure you are not just chasing the steers and confusing them. If the animals do not start and stop on command after the first few sessions, you may need another method or some helpers.

Another option is to yoke a green animal with one that is already trained. The trained animal acts as a restraint and helps calm the new animal. The yoke acts as a more severe restraint than a halter or lead rope, and the green animal quickly learns to follow the more experienced ox. The trained animal must be large enough to hold the unruly animal when he tries to escape. Some teamsters feel this method is the safest and most effective technique for training animals that are large and unruly.

Yoking the animals together and letting them loose to fight the yoke and learn to walk and move together is an option I do not recommend. This method was common in some areas of the United States and is still common in some parts of the world. This method of training works best after the oxen have fought each other and become weary in the yoke, and the teamster steps in. In the process of roaming unsupervised, the animals may learn to move about and do their own thing in the yoke, which most teamsters prefer to discourage. This method also requires a rugged yoke. Even so, the yoke may break, or one or both oxen may choke or be severely injured.

In 2004, I was part of a research delegation exploring Cuba’s agriculture. My specific interest was in oxen, as I had heard the island nation had 400,000 cattle at work.

Most Cuban farmers had abandoned tractors when the Soviet Union collapsed and they lost access to spare parts and subsidized fuel. Fidel Castro then mandated that no bull calves on the island could be killed for a few years, and that farmers should return to using oxen, ensuring that people could grow food and other crops. This program worked to double the number of oxen on farms from 1990 to 1995.

We traveled around Havana looking at urban gardens, meeting with Ministry of Agriculture officials, and seeing historic sites along the way. A few days later our group finally arrived at a large farm cooperatively run by about 40 families in Santa Clara Province. Getting off our small tour bus, I saw my first oxen on our way into the community building of the agricultural production cooperative (CPA).

A group of farmers had gathered to meet with the Americans. There were formal introductions, and then the President of the CPA, Raphael Santana gave an overview through an interpreter of how the farm worked. Then the questions began. The Americans asked questions and the Cubans answered. Most of the farmers seemed less than enthusiastic about meeting with us. At one point I had had enough, as I could see that the farmers, including Raphael, all wanted to be somewhere else.

I raised my hand and asked if anyone would like to see pictures of my oxen. There was an enthusiastic yes. The whole meeting quickly changed, from one of answering questions to real cultural exchange. Everyone got up and gathered around my oxen photos and the articles I gave Raphael. He proclaimed to all that this new information about oxen would be hung in the community center for all to see.

We then immediately left the building to go out and see some oxen. I could not have been more delighted.

As we walked down the country road, numerous teams of oxen and pairs of young bulls were passing us in head yokes. There were ox sleds and carts in the nearby driveway. I shared what I did with my oxen, and the Cuban farmers did the same. Even the interpreter said that it was the most exciting part of our week.

I learned that ox competitions are common, with one held right in the village during the month of July as an attempt to raise ox-training standards. Local schools included draft animals in their curriculum.

The standard in Cuba seemed to be to train young bulls at about age two for oxen. This surprised me the most. The calves that are left to run with the beef cows, I was told, are the wildest, compared to the calves of dairy cows, many of which were Holstein and Brown Swiss.

One pair of young bulls I saw in a yoke had already sired numerous calves, according to Raphael. The pair was dangerous, and I was told to not get too close. The trick to training this type of cattle in Cuba was to use the rings in the nose, chains attached to the rings, numerous trainers with large sticks, and then work the animals hard.

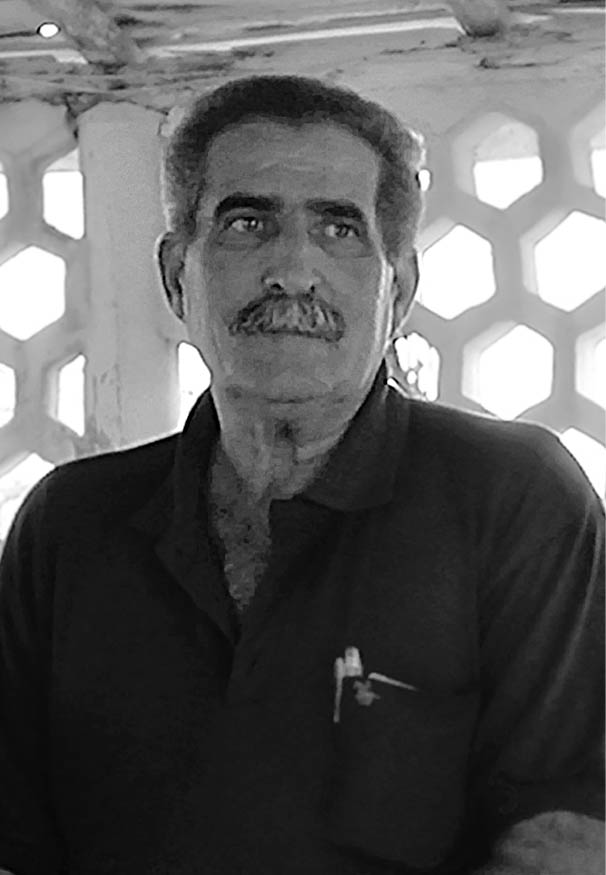

Sometimes the bulls were never castrated, and from the evidence I saw of one 10-year-old bull in a yoke, his battle had been long and hard. He had scars all over, his horns had been cut half off, and a nose ring had been ripped out and repositioned numerous times. Training mature cattle is not something for novices.

The early sessions of training older cattle can be frustrating, discouraging, and tiring. Spend plenty of time working with the animals individually in a small enclosed area to accustom them to being handled, so that when they are in the yoke they will be easier to control. Most teamsters use halters, ropes, and sometimes nose rings to maintain control during early training. The important thing is to maintain control at all times. If just once the animals learn to run away, the habit will be hard to break.