In some parts of the world, oxen are as common as cars are in America. The animals become acclimated to walking long distances and meeting automobiles, trucks, and other animals on the road. In the United States and Canada, most ox teamsters keep their animals for fun and hobbies. The oxen are not usually required to work in the midst of traffic and pedestrians. Yet if they will be taken out in public for any reason, they must be prepared for what they might encounter.

Many ox teamsters have opportunities or invitations to exhibit their animals in public. Holiday parades are popular, and many summer fairs and field days welcome teams of oxen. Other opportunities exist with elementary schools studying local history, living history farms, and competitions in pulls and shows. Oxen adapt well to public situations because they do not easily spook.

Working oxen in public can be great fun because the lumbering beasts are usually calm and easy to work with. As a boy of nine or ten, I vividly remember watching a teamster drive his pair of giant Holsteins using only voice commands and a small stick. From that day forward I was obsessed with having a team.

Oxen adapt well to public situations because they do not easily spook.

While the experiences I have had with oxen in public have all been positive, I have seen many teamsters who were not so lucky. Preparing for the unexpected is the key to safe public appearances.

Oxen on the road in Tanzania learn to avoid pedestrian, vehicular, and bicycle traffic with little direction from their teamster.

Well-trained oxen follow their teamster, watch the teamster carefully, and listen for commands. The animals have to learn to pay attention in all situations. Traffic, sirens, horses, or other cattle can scare a team. An important part of training is exposing your animals to such distractions, which means training them to accept new situations, loud noises, and crowds of people.

Oxen in much of the world wait patiently when given a break from work. Work is as much a part of their daily routine as are eating and drinking. In comparison, oxen in the United States these days often work only a few hours per week, which means the animals have to be trained to stand and wait.

Before taking your oxen into the public make sure they will stop without hesitation and will turn when asked. They must learn to stand patiently.

Distractions you expose your team to should include chainsaws, heavy equipment, other animals, and large groups of children. In parades or other public events where machinery and sirens may be encountered, you must have a team you can control. When I take a young team into the public, I keep a rope on the nigh steer so I can grab it if necessary. The same should be done with a larger team that has spent a limited amount of time in the yoke.

Cattle will not forget a painful or disagreeable experience.

Well-trained oxen are exposed to a wider variety of situations than is the typical bovine. Many dairy or beef cattle will shy from a freshly turned furrow on their way to the pasture. Cattle that have been trained to work should follow their teamster without hesitation, even into areas that might spook other animals.

Following the teamster without question requires a level of trust in humans that goes beyond what most cattle have. This trust and understanding between oxen and teamster come only after many hours of work in a variety of situations.

Cattle will not forget a painful or disagreeable experience. If they have been led to an area where they have fallen down, slipped, or been frightened, they will remember the experience for a long time. Training never stops and a good teamster never leads a team into a situation that the animals are not ready for.

Untrained calves should not be brought before the public unless they are securely haltered and under the control of someone who can handle them if they panic.

Calves are easily and safely acclimated to distractions. With older animals, training becomes more challenging. Animals that have not been exposed to large groups of people or the sights and sounds of parades and agricultural fairs until they are mature are more likely to be scared. Large oxen can be dangerous when frightened, because they are difficult to control if they try to run or jump away from the situation.

Training oxen as calves, as well as getting them accustomed to the public at a young age, is the best way to bring up animals that can deal with a variety of situations. Young teams of steers, however, cannot work long days or bear the environmental conditions that are involved in a long parade or competition.

Calves are also more susceptible to diseases than are older oxen. The stress of trucking, working, and exposure to new things, including unhealthy animals, can all cause problems while your calves are still developing their immune systems. If you want to use a team of oxen in public, plan your purchase and training program so the animals will be at least six months old, and preferably twelve, before they appear in public for the first time.

Work your oxen amid the worst distractions you can create at home, and they will have fewer problems when out in public. I have had my share of mishaps at home. I once had a team turn a corner too sharply, or misunderstand my command, and tear off a wall of an outbuilding.

The only time a team truly got out of my control was also at home, while pulling a stoneboat. As I was walked beside the team I heard a loud hissing noise but could not identify its source. The sound got louder, persisted for a few seconds, and then stopped for a minute or more. My team paid it little attention.

A few minutes later a hot-air balloon basket scraped the tops of the trees just over our heads. The couple in the balloon cheerily yelled hello with a big wave and then released some gas to heat the air and coax the balloon away from the treetops.

The combination of the loud hiss, the shouting people, the basket scraping the treetops, and the giant colored balloon was too much for my team, which took off as if they had lost their minds. It was the first time I felt out of control while working an otherwise well-trained team. I was just lucky it happened at home

Teamster skills are a result of driving your oxen and the experiences you share with them. You can also learn much from other teamsters, whether they are experts or novices, through good observation and asking questions. A teamster never stops learning while training and working oxen. Whether it is a new trick or some training aid, never be too stubborn to learn or teach your animals something new. A good teamster knows when the team is ready for exhibition. Do not exhibit a team that is too green for public display.

Sooner or later, many ox teamsters try riding their oxen. This activity can be impressive to bystanders, but make sure you maintain good control, and do not invite others to join you. Riding an ox is much more dangerous if the animal is pulling a vehicle or implement. A fall from a tall ox is one thing; falling and then getting run over by a scoot or wagon is an altogether different experience.

When oxen appear in public, both the team and the teamster are on exhibit. How people view your team is a function of the time and effort you put into their training. Our history books note the ox teamster as a ruffian whose “skills” included whipping and cussing. This method of handling animals is not recommended, and particularly if the animals are in the public’s eye. A good teamster needs no more than a slight movement of the whip and quiet verbal cues to control the team. Do a good job training your team, because you may be the only ox teamster ever seen by the people you encounter.

A well-trained team of oxen will astonish a crowd. A poorly-trained team or a teamster who is eager to use the whip will sour most people on driving oxen. Do your training long before the day of exhibition. If your team acts up or becomes frightened, blame yourself for not providing them with the proper experience. The best teamsters can anticipate what their teams will do before the animals act.

You can impress the public in any number of ways by showing what your team can do, such as pulling a car in a parade.

When appearing with your team in public, do not lose sight of the fact that the animals have their own personalities and agendas. Different animals react in their own unique ways to various stimuli.

Be prepared for small children to appear suddenly, run at your animals, and grab them in the most unexpected places. I’ve had children climb on the backs of my resting oxen or grab an unsuspecting ox by the sheath hairs in the middle of its belly.

I once had a pair of yearlings that hated small children. It took me some time to figure out why they disliked kids. Then one day I caught my three-year-old brother in the barn whipping my oxen as they stood in their stanchions. You cannot be with your team all the time. You can never know all that a team has seen or been exposed to. You never know how a team will react until they are put in a situation. But you can get to know their idiosyncrasies and how to control them. Learn to make wise choices as a teamster.

When out with your team among the general public, do not leave your animals unattended. People will tease them, try to grab their horns, and attempt to pet them without asking your permission beforehand. Make it a practice to let no one touch your team without your permission. If people ask to pat your team, let them do so in a controlled manner, preferably one person at a time.

Sometimes large groups of people, especially children, will run in from all directions to grab and pat a team. They don’t know enough to respect the animals, their tremendous strength, and the dangers of being stepped on, kicked, or poked with a horn. Because oxen are slow and generally calm, people forget that they are large and can cause injury just by turning their heads or stepping on a toe. The public must be educated.

Whenever you show your team in public, be ready to answer a barrage of questions about them. Most people think of oxen as just huge beasts they have read about or seen in books. They have no idea what kind of animal an ox is, let alone the amount of time that goes into its training. Being prepared to answer questions about your team is the best form of public relations an ox could have.

Be sure your team is well adapted to the kind of exhibition you attempt. Cattle can easily handle parades, which are often less than a mile or two long. Wagon trains or all-day exhibitions are much more exhausting. Hobby teams that are worked only a few hours each week need to be conditioned before attempting such an event.

Many exhibitions occur during warm weather, when temperatures make it comfortable for humans to be outdoors. A fine temperature range for working cattle is 50 to 60°F. Be wary in warmer weather if your cattle are not adapted to such conditions. Cattle, especially Bos taurus or European breeds, do not tolerate heat as well as horses, mules, or Zebu-type cattle.

Frequent watering and hosing off will greatly aid the comfort level of your team, especially in high temperatures and humidity. Cool weather is more appropriate and comfortable for most working cattle. Be particularly careful with calves, because they easily become overheated and dehydrated.

I was once in a wagon train that was to cover about 20 miles a day. The event looked fun and exciting. My three-year-old Dutch Belts were fast on their feet and full of energy. In an eight- or ten-hour day the planned speed seemed appropriate for my team and me. I had never been on a wagon train with horses and pony teams, but I soon found out that we weren’t going to travel at 2 to 3 miles per hour, the comfortable speed for oxen. In the first two and a half hours the wagon train traveled 12 miles, including two 15-minute breaks. The horse teams were traveling at about 6 miles per hour.

My oxen kept up for about 6 or 7 miles, but I had to trot them down hills. After the first hour it was obvious that my team couldn’t maintain that pace. My first wagon train ended at noon on the first day. My animals were not prepared for traveling at such speeds, and the hot weather complicated the stress they faced going up and down the mountains.

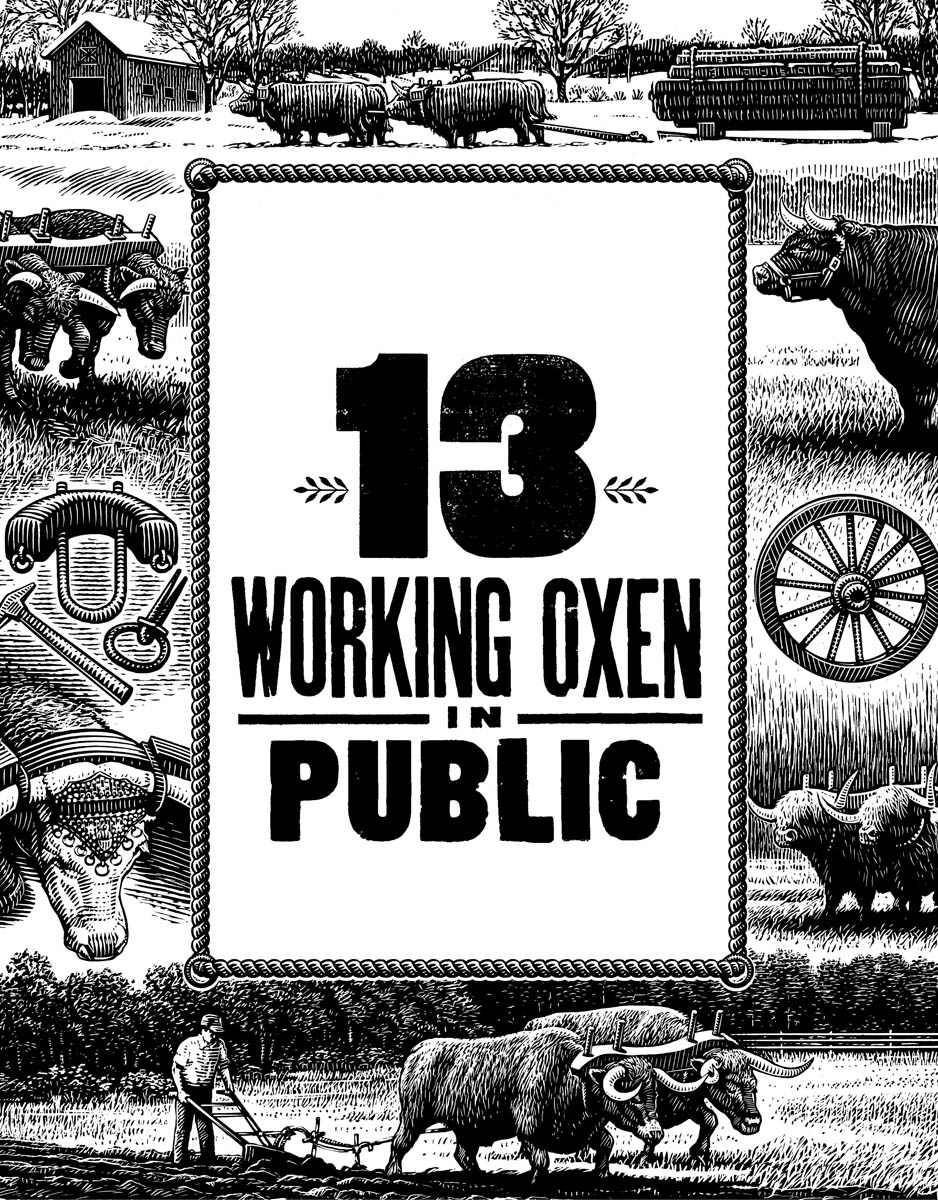

Any animal presented to the public should be in good physical condition and well-groomed. No one is impressed with cattle that have urine stains on their bellies and legs and manure caked to their hair. Most cattle will stay relatively clean if kept outdoors in a clean lot or pasture.

Oxen that are kept indoors, especially in stalls designed for cows, quickly become stained and dirty because they urinate under themselves, and they lie down more than other draft animals. Before showing them in public you may need to wash your animals. Cattle that are accustomed to being washed learn to enjoy it, especially on hot days, provided you don’t squirt water or soap into their eyes or ears.

A well-groomed team with hair clipped, brushed, and washed, horns sanded and polished, fascinates the general public. To add to the impressiveness of a team, many teamsters add brass horn knobs, bells, and a masterfully carved yoke and whip. These all portray a wonderful image of the animals and the teamster.

Washing steers or oxen makes them look their best for a parade, show, pull, or other public event.

In lining up for a wagon train, parade, or other public event, the last position is usually best because oxen walk slower than most other animals or humans. Avoid walking near a band or fire department because the loud unexpected noises they generate can spook even a well-trained team. On the other hand, oxen pulling a cart or just walking in a yoke often spook horses. Since oxen adapt more readily than other animals, be respectful of other participants.

Be sure you and your team have worked with the implement or wagon you plan to pull in a public event. Maneuvering a large wagon or cart takes some getting used to by both the teamster and the team. If you will be traveling up and down hills with a large wagon or cart, your team must be accustomed to holding back a load. The dangerous combination of a heavy wagon, no braking device, and a team without shoes or experience in holding a load can lead quickly to disaster.

When working large animals in public, invest in some type of insurance with a liability policy on your animals in case they do run away or get out of control and cause property damage or injury. Many farm/homeowner insurance policies can include such coverage. Insurance is usually cheaper and more readily available if you assure the insurance company that the general public will be only viewing your animals and will not be invited to ride in your ox cart or wagon.

If you do offer rides, take extra precautions. Although runaways are not likely with a well-trained team, there’s always the chance your animals will get spooked and jeopardize the passengers’ safety.

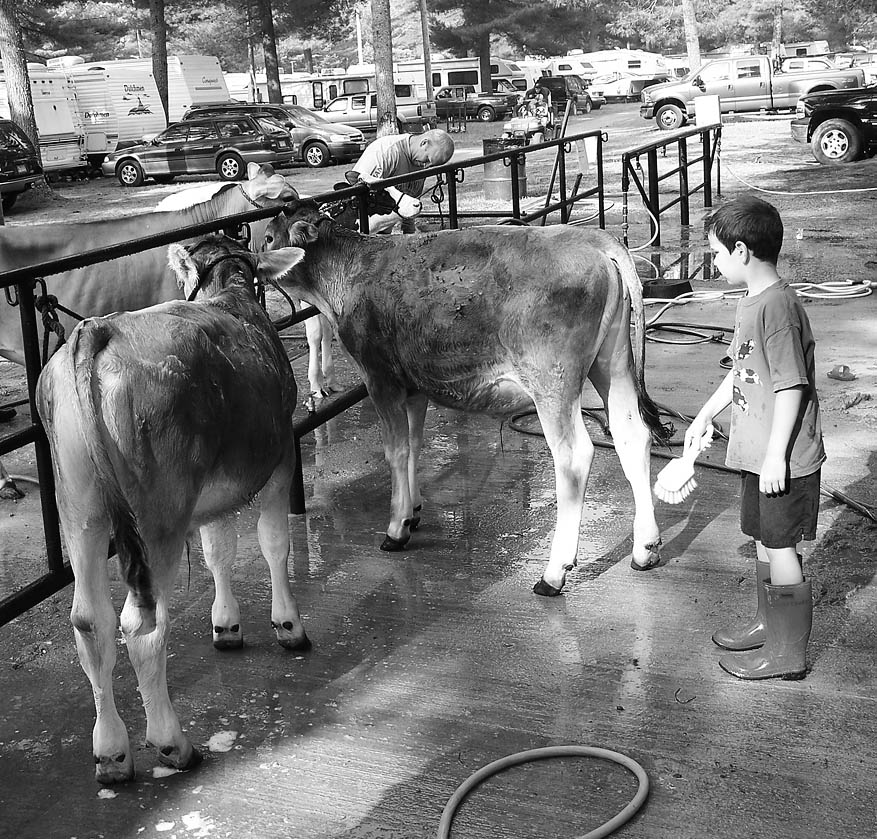

Beginning with a bet that he could train a steer to be ridden, retired dairy farmer Bill Speiden started working with oxen in 1978. “Art Hine stopped by the farm on one of his trips to Williamsburg with a team,” Bill recalls. “He got me straight on how to make a yoke and a number of training tips. I bought my first-off farm-made yoke from him and used it as my prototype for additional yokes since then.”

I first met Bill at an ox training workshop I was helping run in Missouri in 1995. His genuine interest in oxen and history was obvious. He asked more questions than most participants and really wanted to improve his training and driving techniques.

His oxen have taken him as far as the Bozeman Trail in Montana and Wyoming, where his team pulled a wagon for 300 miles, and to Idaho, where he worked for the Oregon Trail Center. These days he typically attends 10 to 14 events a year closer to his home in Somerset, Virginia. In addition, however, he loads up his teams for the annual trek to Tillers International in Michigan for the Midwest Ox Drover’s Gathering.

“I feel that public exposure to oxen and their history is an important contribution to people’s grasp of the real world of the past,” Bill says. “Being kind of an adventurer, I really enjoyed the wagon trains, giving me and my helpers an opportunity to experience taking the oxen over 300 miles on an outing, and getting as much as possible of a feel of what it was like to travel that way in the 1700s and 1800s.”

Bill has worked with many breeds, including the Holstein, Brown Swiss, Ayrshire, Milking Shorthorns, Dutch Belted, and an all-black team that was a cross between the Brown Swiss and Holstein.

He says, “The Holsteins worked well in crowds for me, and were easy to teach to plow. Pure Brown Swiss and Shorthorns can be laid-back to a fault. The Holstein–Brown Swiss cross worked well for me, but they tended to get up over 3,000 pounds each, and that 75-pound yoke kept getting heavier every year. I have settled on the Milking Shorthorn–Holstein cross as my favorite. They rarely get much over a ton each, and the red or blue roan coloring are historically correct for early America.”

Bill’s most memorable moments have included: “All the local people in Montana and Wyoming coming out to see the oxen at campsites along the Bozeman Trail.” He also said he enjoyed taking the oxen and wagons through streams and up the banks of rivers, where the horses and mules could not go.

Watching Bill’s slide presentation at the Midwest Ox Drover’s Gathering in 2002, a few things stuck out in my mind. First, Bill had to shoe his oxen when they lost shoes on the trail. Throwing a 3,000-pound ox down and shoeing him tied up on the ground was no easy task, possibly resulting in the animal breaking someone’s ankle while tossing his head around. To hear Bill tell the story of his time on the trail, you know it was a lot more than just working oxen in public.

Bill’s knowledge of the history of the trail and the use of oxen were second to none. There is no doubt that he truly experienced a little part of what he regularly tries to recreate.

Exhibiting oxen in parades and competitions and at field days and living history farms or schools can be a wonderful experience. The presence of a well-trained ox team is often the highlight of such events. Oxen adapt well to being in the public eye because they do not spook as easily as other livestock.

Although sharing your experiences with others and impressing a crowd with your well-trained team is fun and rewarding, always remain aware that an unanticipated occurrence may frighten your team. A good teamster is able to predict a team’s actions, but even the best teamster cannot totally anticipate their reactions. Never put yourself or anyone else in a dangerous position with your team. Mature oxen are so large and powerful that safety must always come first.