Throughout the northeastern United States numerous ox competitions take place, most often in conjunction with agricultural fairs. These events offer ox teamsters a chance to compare their animals, training techniques, and equipment. The draft animals, people, and equipment provide a superb environment for demonstration, questions, and casual experimentation. Competitions have facilitated working oxen remaining in New England in particular because they inspire young people to challenge themselves and adult teamsters to compete in order to challenge their fellow teamsters year after year.

Ox competitions have been popular for centuries, historically sponsored by agricultural societies with the primary purpose of sharing information and spreading technology. The original New England ox competitions provided an outlet for fun and entertainment where teamsters could gather and compete with animals normally used for work around the farm or in the forest. Animals were walked many miles to compete in local events.

The contests set standards for local teamsters. Animal training levels, equipment, and techniques all benefited from the challenge of trying to beat your neighbor in friendly competition. Well-matched and beautifully trained teams became the norm, and competitions ultimately raised the level of teamster skills and animal abilities.

Teams were pitted against one another in pulling competitions in order to see who had the strongest team. Classes were put together to see how well-behaved and trained the teams were. Teamsters would hitch the animals to a cart or wagon and maneuver them through a variety of obstacles. Judges assessed their ability to handle the demands placed on them and the teamster’s ability to control them in challenging situations.

Plowing was an important job for oxen on the farm, and many agricultural events included plowing competitions. Classes were later developed to evaluate individual animals and teams based on their appearance, conformation, and how well they were matched.

Early events both praised and scorned the ox teamster. Competitions in Massachusetts that raised the level of teamster skills were praised by agricultural societies, while the same groups often looked down on pulling competitions. In areas where logging was more common, such as the northern forests of New Hampshire and Maine, pulling competitions were more popular. Oxen used in the forest were accustomed to pulling heavy loads and their teamsters were at ease with asking their animals to push themselves to their physical limits. Many early New England documents display the differences in philosophy among — and sometimes outright challenges to — teamsters of other regions.

According to historian Jochen Welsch, who has studied the use of oxen in New England:

“Oxen represented the sinews of the region’s agricultural strength, and it is no surprise that Yankee farmers took every opportunity to celebrate the animal that had become part of their heritage.”

Ox competitions continue today in the United States, but most animals and teamsters have become specialists. Few teams are used regularly for farm work, logging, competition pulling, obstacle courses, plowing contests, and showing. The teams used for pulling are often well trained and powerful but sometimes lack the desired conformation or other characteristics needed for showing. Show teams are well groomed and well matched but are not usually as well trained or physically conditioned for work and therefore carry extra flesh. Teams used for plowing and log scoot competitions tend to be the least specialized, and both show teams and pulling teams might compete. Only the occasional team used in the field or forest is somewhat specialized in the “old” skills. Even less common is a team that can successfully compete in all four types of event. Some competitions do not allow animals to compete in both shows and pulls, forcing teamsters to specialize.

While a good team can do well in all styles of contest, teams trained by 4-H children are the most likely to be able to compete at all levels. This is the result of lots of time and effort spent training, rather than some unique ability or developed skill.

Internationally, competitions have the potential to raise skill levels. Peace Corps volunteers and mission workers tell stories of exceptional teamsters in developing countries who have become the standard toward which local teamsters strive. Such examples are good lessons for development projects or extension workers attempting to introduce oxen and related technologies. Well-trained animals and teamsters will always inspire others to adopt technology and new techniques.

Oxen are shown in New England as other cattle and livestock are shown in other regions. An ox show normally consists of numerous classes designed to exhibit working cattle that are well trained and well matched as pairs and display outstanding conformation. Competitions also challenge the teams to demonstrate their abilities as work animals.

A single official judges most events, although team judging is sometimes practiced. Both open shows (for teamsters of any age) and 4-H shows (strictly for youth working with their 4-H clubs and projects) are common at agricultural fairs. Shows vary in size and scope depending on the location, interest of ox teamsters, and premiums paid to teamsters for exhibiting. Classes vary with the region and local customs.

Ox teams in New England are expected to work without halters, bridles, nose rings, or other restraints. The cattle are directed with voice commands and the use of a stick or whip.

Most open shows include a conformation class where teams are judged on their conformation, body condition, and how well two animals in a team match. Many teamsters spend a great deal of time selecting animals and feeding them appropriately for this type of show.

Evaluating conformation begins with a careful examination of each animal for serious injuries or conformational defects that would lower the ox’s value in the yoke. The oxen are then evaluated for general appearance. They should have straight toplines, strong straight legs, and strong shoulders and necks. Adequate muscling, condition, and body size for their age and breed are also judged. The hooves should be properly trimmed and free of disease. The animal should be able to move and walk easily.

A challenge in judging one animal against another is that one may have weaknesses or strong points that must be accounted for in comparison with other teams. No set rules or scorecards have been developed for judging the conformation of oxen. A good cattle judge can determine which cattle appear healthiest and most trouble-free, and which display serious conformation problems. Cattle of any breed may be exhibited as oxen, and breed character must be taken into account. Personal preferences about color, breed, or origin should not be part of the judging process.

An ox is not a dairy or beef animal and its conformation should be so judged. It should not be thin and angular like a dairy cow, nor should it be round and fat like a beef steer. A good judge understands that adequate body condition and muscling are essential, but that oxen must display the characteristics of an animal ready for work.

Working classes are the highlight of any ox show. A well-trained team can display a level of training that inspires awe in the audience. Even farmers who raise beef and dairy cattle may be surprised to see how well oxen respond to subtle cues from their trainer.

A working class has a prescribed course through which the teamster must direct the team. In an obstacle course the team pulls a sled or cart. The best-trained team is one that demonstrates good response to the teamster’s cues and that can go through the obstacle course without hitting anything. Yelling, whipping, grabbing the yoke, and pulling or pushing the animals are all frowned on, particularly in a class testing ability to work in the yoke.

Some judges encourage the teamsters to demonstrate any special tricks their animals have been trained to do. The teamster might back the team from behind while not touching the animals, call them to come from a great distance, or take off their yoke and direct them as a team or as individuals. Teamsters have also been known to ride an ox, or direct their team through the obstacle course using voice commands while riding in the sled or cart.

New England’s young teamsters train their steers so well that judges are encouraged to challenge them with seemingly impossible obstacle courses. Nevertheless, many competitors have no trouble meeting such challenges.

Animals at a show must look their best and be so exhibited as to demonstrate their strengths and downplay their weaknesses, while wearing no halter and using no lead rope.

Ox teamsters go to great lengths to find two animals that match in color, conformation, horns, weight, and disposition. Many teamsters specifically mate related or even twin cows to a particular bull to maximize their chance of getting two calves that will be similar in all regards when mature. Matching two oxen as closely as possible increases their attractiveness and value, as well as their ability to work more effectively in the yoke. Animals of different breeds, size, or disposition may be a challenge to train to work effectively as a team.

Since beautifully matched teams sometimes lack perfect conformation or working abilities, this class gives teamsters a way to exhibit and compete with animals that may be neither perfect in conformation nor trained to pull a cart. Occasionally, pairs of matched teams are yoked together for four-ox or larger hitches to demonstrate the teamster’s ability to select large numbers of matching animals.

A best-matched class allows teamsters to exhibit their beautifully matched teams against others. This class tests a teamster’s animal selection skills and ability to care for and feed two animals so that they do not grow apart. Most judges evaluate how well the team is matched in color, color patterns, bodyweight, conformation, movement, disposition, horn length, and horn shape.

Oxen were historically worked until they were about eight years old. When the animals began to slow down and had maximized their size and weight, farmers often sent them to market. Colonial New England farmers considered oxen a sound investment because they not only worked for most of their lives but also provided additional income at the end of their working days. Cattle may live beyond the age of eight; many have worked until they were twice that.

The market value of mature cattle in the past was higher than it is today. With this understanding, some agricultural fairs continue to have fat classes to judge the beef characteristics of oxen. Even today, most oxen eventually end up on the table, although the value of fat oxen tends to be ridiculously low in today’s market.

Cattle deemed too heavy to place well in conformation or working classes often place high in fat classes. For some ox shows this class provides a mechanism for spreading out the premiums and ribbons among pulling oxen, working oxen, and those considered to be show oxen. Some shows go to the extent of barring any pulling animals from showing, working animals from entering fat classes and fat oxen from competing in other events.

Youth and 4-H shows allow young people to exhibit their animals in an environment that is less intimidating and often more rewarding than competing against adults. A great advantage to these shows is that each team’s performance is the result of the young teamster’s own time and effort.

Although most 4-H programs encourage parental leadership, the majority of the work on any project should be done by the youth. Oxen work best for the teamster who trained and understands them. A high purchase price, animals trained by parents, and the selection of a beautifully matched team shown by a youngster who did not put in time and effort readily become obvious in a youth show.

Most youth shows include a number of classes such as fitting and showmanship, best-matched pair, cart or working class, and stoneboat performance class. A conformation class is not usually included.

Oxen are work animals, and training and care are the focus of the 4-H program. Less-than-perfect conformation should not influence the teamster’s ability to compete effectively in working, best-matched, or showmanship classes. A lack of conformation classes allows youngsters to compete on an equal basis even though they may not have chosen their own animals or perhaps could not afford animals with perfect conformation.

The judge’s role is to maintain a professional yet challenging environment. Judges should be carefully selected and required to encourage good ox training and showing skills. To assist the youngsters in perfecting their skills, a good judge offers constructive comments and some positive feedback for every young teamster.

4-H shows present every child with a ribbon and prize based on the Danish System, where blue, red, or white ribbons are given depending on the quality of the performance. Blue ribbons are presented for an excellent performance, red for a good performance, and white for an adequate performance.

A working steer or ox project involves more preparation than other 4-H projects. The animals require not only year-round feeding and care, but also training. That training takes a lot of time, commitment, and planning. Good leadership and lots of encouragement and direction are important for beginning teamsters. Oxen cannot be trained to work a few days before the show. Training must begin months before the show and ideally continue on a daily basis. Young teamsters rise to the occasion by regularly amazing audiences with their skills in training and working oxen.

This young teamster has no trouble directing his steers to back a cart while keeping the wheels on 3" planks.

A 4-Her does the seemingly impossible by directing one wheel over a block of wood and stopping on top.

The fitting and showmanship class is typically the first class of any 4-H show. Both the animals and the equipment are expected to be immaculately clean and in excellent condition, while the teamster shows the animals to their best advantage. Most teams are clipped to enhance the animals’ appearances. Working steers and oxen are supposed to be masculine work animals, so are not clipped like dairy cattle.

The recommended procedure is to body-clip the steers one month before the show, shortening the hair coat yet allowing time for it to grow out and look normal. Animals that are body-clipped just before a show often appear uncomfortable, may be prone to sunburn, and have hair that sticks straight out instead of lying naturally. Many 4-Hers clip their steers or oxen before the show season starts, which lets short new hair grow for the season. This practice eliminates the need for the animals to shed out and makes their coats easier to wash.

Clipping the coat enhances an animal’s appearance by bringing out his strengths and minimizing his weaknesses.

Hair in the ears and under the belly and sheath is clipped a few days before the show to give the animal a clean, lean appearance. Some teamsters clip the topline straight to enhance the appearance of the back. Clipping may both enhance strengths and minimize weaknesses.

Regular grooming is important for show animals. Use a bristle brush to remove dirt, dandruff, and loose hair and to accustom the animals to being handled. During warm weather, regularly rinse the animals with a hose to remove dandruff, dirt, and debris in the haircoat.

Well before the show, completely wash your oxen numerous times with soap to remove manure or tough stains. Just before the show, wash the animals to remove dirt from deep within the coat and enhance the coat’s shine. Clean the hooves and horns, and sand and polish the horns.

The grand event for New England 4-Hers is to represent their states at the Eastern States Exposition in Springfield, Massachusetts.

While no set scorecard or criteria exist, many New England 4-H shows use a scorecard similar to this:

Plowing contests require a judge, a field to be plowed, and rules for the competition. The contest evaluates both the teamster’s ability to control the oxen and the team’s ability to plow adequately in a timely fashion. Plowing is a difficult job for a team of oxen. Depending on soil conditions, plowing can create a tremendous challenge for the animals to overcome. Plowing contests have for centuries been a way to test both the working ability of cattle and the skills of their teamster.

Plowing was a necessary part of colonial life, so plowing on early farms was an important job for an ox team. The animals had to be willing to pull a plow through rough stony fields, follow a furrow, and work for hours on end. A well-trained team could do the job easily, but a poorly trained team found it difficult. Most oxen had plenty of opportunities to develop their skill and muscles on the job. Today’s teams spend much of their time in a pasture or barn, with little or no time spent in the furrow.

Teaching a team to plow requires both good control over the animals and oxen that are ready for the job. Training takes two people, one on the plow and another driving the cattle. As the animals become acclimated to the job they may be trained to plow with just one person to direct the team while controlling the plow. Both plowing with oxen and driving oxen from behind are challenging. The ability to combine the two truly tests the proficiency of both the animals and their trainer.

Many farm museums and living history farms sponsor plowing contests to attract the public and offer fun for draft animal owners.

Here is a set of possible judging criteria for a plowing contest:

Many agricultural and forestry events feature log scoot competitions. In New England, oxen were once used to twitch logs to a common landing, load them onto a scoot or bobsled, and haul them down a trail. Competition events may combine all three components or consist of just twitching or hauling a scoot through an obstacle course.

If the log scoot competition combines all three parts of a logging operation — twitching, loading and hauling — it is a challenging and lengthy event. These events are judged using time and accuracy in maneuvering the scoot as the basic criteria. Generally the log scoot component is the most difficult because the load is heavy and must be navigated through a tight course consisting of right and left turns and specific starting, stopping, and resting areas. To be fair to younger and smaller teams, most competitions are divided into classes by weight or age.

The sport of ox pulling has changed little over the past 150 years. This unique part of New England culture has never drifted far from our stony hills.

Historically, teams were accustomed to long days and heavy loads. They usually spent the winter logging and the warmer months in the fields. Such teams were smaller, leaner, and tougher than the average teams today. They knew what it was like to work 8 to 12 hours a day drawing heavy loads, plowing rocky fields, or walking 20 miles with a heavy cart. Competitions demonstrating the team’s skill or strength allowed early farmers and loggers to show off the fruits of their labor.

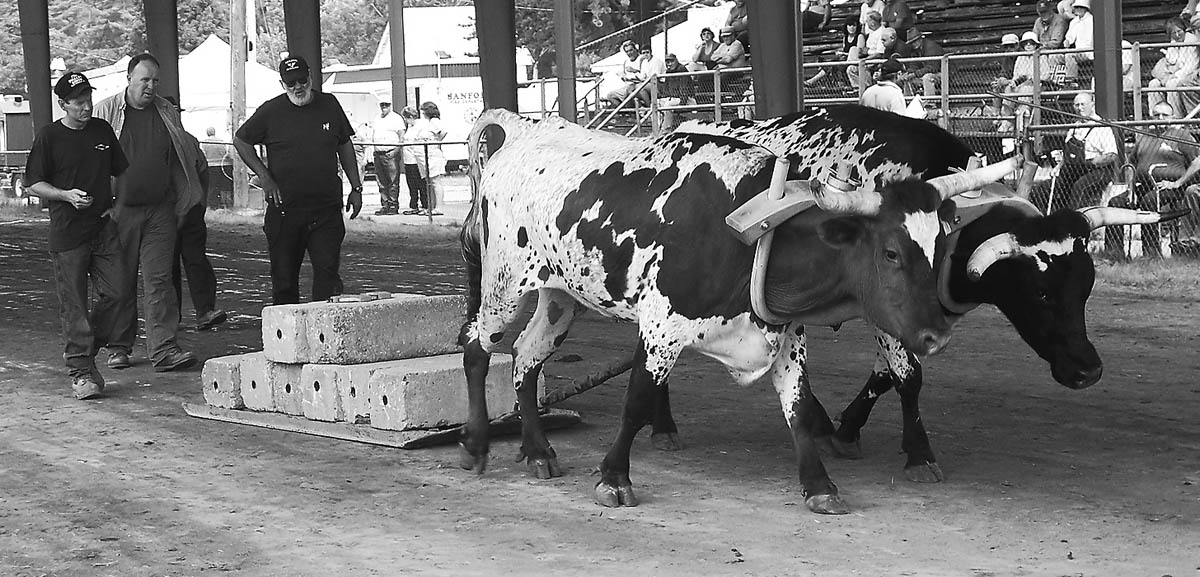

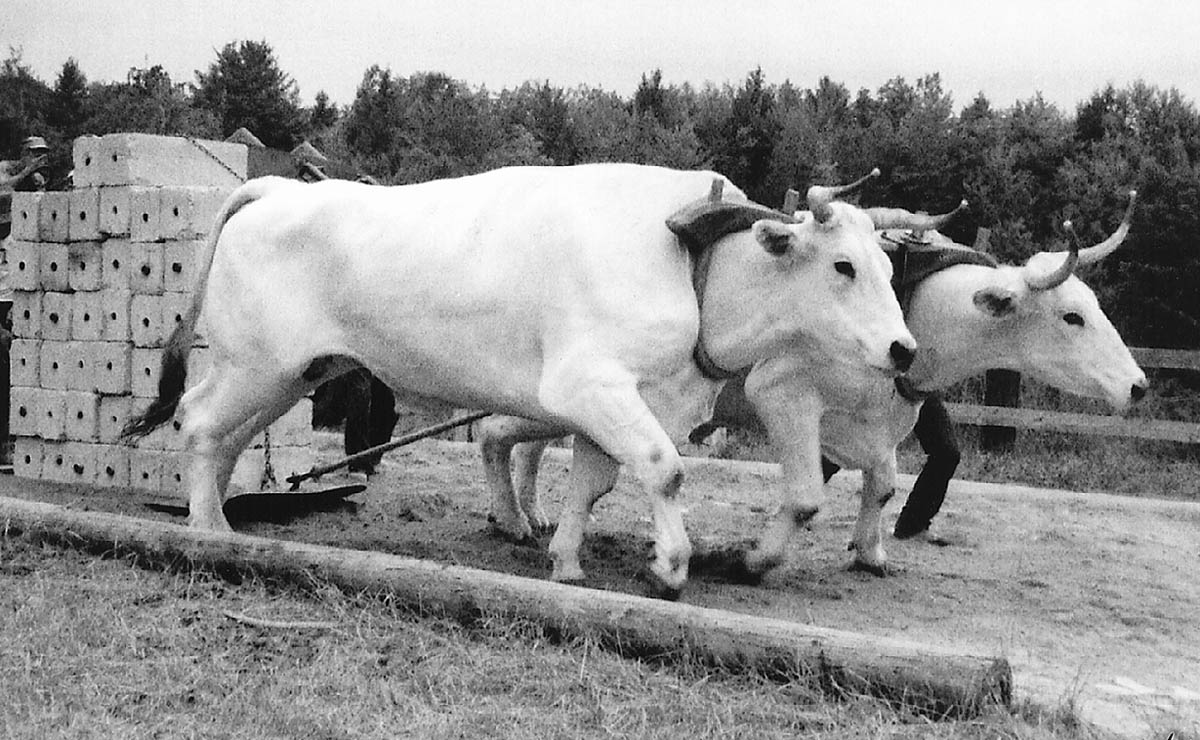

Today ox pulling remains similar to early descriptions. The cast of teamsters, the animals, the yokes, and the keen competition are all the same. The loads the animals pull are tremendous and hard to believe possible. Loads of 15,000 pounds of cement are frequently moved over dry gravel on a flat New England stoneboat and loads in excess of 20,000 pounds over wet gravel. Surely such animals deserve more admiration than they have received.

Most modern-day teamsters consider pulling a sport or hobby. It is a way to work with animals, get together with friends and enjoy a unique cultural competition. Oxen competitions are no longer an integral part of society, nor are teams as common as they once were. Yet in recent years, at fairs such as the Fryeburg Fair in Maine, more than 400 ox teams have been exhibited.

Dozens of competitions occur in Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, and Massachusetts each year. Competition season begins in early summer and continues until the grand finale at Fryeburg in mid-October. Many teamsters spend the entire season following competitions, some attending up to 50 different events in a season. They take time off from work or use their vacation time to pursue a sport that once involved walking a team to the local fair.

Animals in the contests vary as much as the people who flock to the fairs to watch the pulls. They come in all colors, shapes, and sizes. The largest animals are usually the Chianinas, dwarfing the fair’s largest draft horses. At the other extreme is the tiny Dexter, which weighs only 800 to 1,000 pounds at maturity. The old New England favorite has been the Milking Shorthorn, often called Durham by ox teamsters. In recent years Milking Shorthorns have lost ground to more exotic breeds and various crosses.

Cultural differences sometimes arose in competitions, as demonstrated by an article printed in the New England Farmer in 1842. A Maine ox man challenged teamsters from Massachusetts with the following statement, after reading that teamsters at the Worcester Cattle Show were hauling two tons of stone on a flat stoneboat.

“Two Tons!! why that isn’t a load for a pair of Kennebec calves. We saw Peleg Haines of Readville, at the drawing match at the Kennebec Cattle Show the other day, hitch his single yoke of oxen to a load that weighed six tons five hundred and ninety, and walked them up a hill just as easy as you would a wheelbarrow. When he got to the steepest part of the way, he stopped them a moment, just to show the spectators how easy they could start it again. At the word they moved forward as readily as they did at the bottom — no wringing, twisting, or fuss about it. None of the oxen drew less than 8,500 pounds.”

Pulling teams are divided into classes by weight. The two animals in a team have to meet certain weight requirements, often forcing teamsters to use animals that are not similar in size or color. The weight classes are usually in 400-pound increments beginning with calf classes, where the combined weight of the team does not exceed either 1,200 or 1,600 pounds. Most of these events are limited to children either 14 or 16 years old.

Some fairs prefer not to have calf classes and begin their ox pulls with teams that weigh 2,000 pounds. In years past many pulls used a tape measure to determine weight classes, where the heartgirth of the ox determined the class. Both weight and heartgirth have their disadvantages because competitive teamsters are creative in finding ways to meet the requirements for their preferred weight class or division.

Pulling competitions vary according to local customs, and each has its challenges. Many teamsters prefer just one type of pull and train their cattle accordingly. Other teamsters do well in any style of competition. Exceptional teamsters with exceptional teams are needed to excel in the three main styles of pull.

In Maine, the distance pull is the most common ox pulling competition. The animals are hitched to a load, ranging from 75 percent to 160 percent of their bodyweight, and are tested on how far they can pull that weight in either 3 or 5 minutes.

Larger cattle, weighing in excess of 3,200 pounds as a team, generally pull the heavier percentages using a 5-minute time limit. These large cattle classes consist of mature oxen with many years of experience. Other big ox classes include the 3,600-pounds class, the 4,000-pounds class, and the free-for-all or sweepstakes teams, which have no upper weight limit. The bigger the ox, the better.

Younger cattle pull a lighter proportion of their weight for a shorter period of time. Many of the “calf” classes are strictly for children, who completely direct and control their animals; other young people may assist with hitching the team to the stoneboat. Classes start with animals that weigh a combined 1,200 pounds or less as a team. Although these competing teams are just calves, most teamsters will tell you, “the sooner you find out if a steer or young bull has what it takes to pull, the less time you’re going to waste on training one that doesn’t have the moxie.”

The distance pull for adults requires each team to take a load of 100–150 percent of their combined bodyweight and pull it as far as they can in either 3 or 5 minutes.

At any fair the free-for-all is the highlight of ox pulling, drawing standing-room only crowds. The gargantuan animals are usually slow and calm, and tower above their teamsters. The loads they draw are tremendous.

In New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Vermont, the 6-foot elimination pull dominates, where each team pulls a loaded stoneboat 6 feet in one continuous motion. Each team is given three attempts. If they fail to pull the load 6 feet in three separate attempts they are eliminated and may not continue to the next load. The winning team draws the heaviest load the farthest distance. In tough competition, none of the teams can move the final load the entire 6 feet. The team that moves it the farthest wins.

Many of these competitions are held in indoor arenas and tremendous loads are pulled. Free-for-all teams have pulled more than 20,000 pounds of concrete blocks on a stoneboat. With proper training a team can generate huge bursts of energy to pull these enormous loads. To do well the animals in a team have to be in almost perfect sync.

In the free-for-all class, large oxen, like these Chianinas weighing in excess of 6,000 pounds, pull loads of more than twice their combined weight.

A third type of competition sometimes seen in New England is the Nova Scotia pull, where teams from Nova Scotia challenge New England teamsters using Canadian rules. The teams are hitched to one load on a 10-foot-wide track. Each time the team moves the load 3 feet, it qualifies for more weight. The team that pulls the greatest percentage of its own weight 3 feet in a straight line is declared the winner.

In the elimination pull, a team has three chances to pull the load 6 feet in one continuous motion.

Most New England teamsters who compete start working their animals in the early spring just after the snow melts. Some teamsters never take time off and work their teams all winter in the woods and at gathering maple sap in the spring. They step up the training in the spring to “harden the animals up.” A good ox will not forget how to pull, but the teamster must see that the team is conditioned and ready for competition.

Animals used for pulling must have a strong desire and willingness to work in the yoke. A reluctant animal can rarely be made into a champion pulling ox. A good teamster usually has cattle that work easily and pull willingly. If betting came to the ox-pulling ring, the odds would be low because the teamsters’ skills play a large role in the ability of the animals.

As the old adage says, “an ox is not born, he is made.” The teamster who knows how to train cattle can get the most out of them. Each animal has his own personality and disposition, and some are easier to make than others. A winning teamster culls oxen that don’t have the disposition to pull. Training a steer that enjoys and willingly does his work is easier than forcing an animal to do something he does not enjoy.

Most teamsters start training by walking their animals long distances with a light load. They may then step up the weight and shorten the distance the animals pull. They are building up the team’s stamina and wind, then following with muscle and skill building. The greatest mistake many teamsters make is trying to get their animals to pull a large load when they are still young or out of shape. Nothing discourages a young team more than a heavy load they cannot move. The team will remember the experience. Regaining their confidence will take a long time.

Oxen often convince inexperienced teamsters that they cannot possibly pull a certain load. Cattle, like some people, will do the minimal amount of work required. They may refuse to pull out of laziness or they may not know how to draw a heavy load. Many cattle do not realize their own strength until a seasoned teamster provides the right training. Cattle are lazy animals, but once they realize that pulling is part of their life they usually cooperate.

The oldest oxen seen in New England are usually the good pulling cattle. Regular exercise, a controlled diet, and good strong feet and legs help the animals survive to a ripe old age. A common line heard near the pulling ring from old teamsters is “a good team will live long enough to vote.” In truth an 18-year-old team is a rarity because the natural life span of cattle is only about 10 to 12 years. Healthy robust cattle of that age are sometimes found, though. Many of the fancy show oxen that are not regularly exercised become overweight, which leads to feet and leg problems and premature culling.

Training cattle to pull in competition is more challenging than training a team to log or pull a cart. More time, more commitment, and a greater understanding of the beasts are needed. While many young children can train a team to work, few understand how to train a team to compete effectively in New England pulls.

Year after year, the training of pulling cattle inspires teamsters to spend countless hours practicing and getting teams ready for competition. The key to success is a team that is well-conditioned, with lots of stamina, experience in the yoke, and a knowledge of how to push a heavy load upward and forward. A team that learns to “lift” the load reduces the friction on the ground and thus makes the load move a little more easily, giving them the edge in the pulling ring.

A successful competitor like Frank Scruton of Rochester, New Hampshire, with more than 50 years of experience in the pulling ring, says the key to winning is well-trained cattle that put on plenty of miles with a light load. “Once a team knows how to pull heavy loads,” says Frank, “you don’t have to hitch them heavy very often, just enough so they don’t forget. And don’t hitch them so heavy at home that you discourage them.”

Not far from the Atlantic Ocean, just north of Portland, Maine, is the Marston homestead, 45 beautiful rolling acres of fields and woods, home of Mark and Kim Winslow and their children Stefan (18), Justin (14), and Marissa (13). Mark grew up across the street from what was then his grandmother’s family farm.

Entering their home, it is hard to miss the numerous historic photos hanging on the wall in their home office or ox trophy room, as they more fondly call it. The room has dozens of trophies their children have won with their working steers over the last 10 years. Hanging also are old photos of Mark’s grandfather and his Uncle Lester Marston’s oxen plowing, haying, and even pulling a car out of the mud in the early 1900s. Mark proudly states that “For six generations oxen have been kept on this farm.”

Mark and Kim bought the farm from family and have made many improvements to the house and property. Before moving here, they lived in Raymond, Maine, where they began their family. There Mark rekindled his interest in oxen and got his oldest son Stefan started with a young team. Mark was a 4-Her from 1966 until 1976, a member of the Brass Knobs 4-H club, to which his children now belong. Mark noted that this was just a few years after Bob Young and other parents started one of the first-ever 4-H clubs for working steers and oxen in the early 1960s.

The Winslow children have always impressed me with their teams and the obvious work that has gone into them. Mark and Kim take the kids and steers to about 20 events a year. They travel all over New England to living history farms, plowing contests, farmer’s pulls, ox workshops, and, most often, agricultural fairs that host 4-H Working Steer shows.

The kids all started in 4-H when they were 8 years old, and Stefan says he is now retired from 4-H, after 10 successful years. He always had Milking Shorthorns except for his last pair, which were Chianina-Holstein crosses. He will attend the University of Maine majoring in Construction Management, and Mark hopes he’ll return to work in the family business.

Justin has had four pairs of steers: two pairs of Milking Shorthorns, one pair of Devons, and his current pair of Devon-Lineback crosses, a striking red color with a narrow white stripe over the rump and tail.

When asked his advice for a new teamster, he replied, “You have to work with them every day, and never give up.”

Justin enjoys competing in shows with people from other states and clubs. A serious competitor, he admits he likes to win. He has always demonstrated great sportsmanship in the show ring, however, and when he does not win, he simply goes back home and works his steers to make sure they are ready for the next show.

Mark added, “Four out of five years, Justin has won the plowing match at the Billings Farm, in Woodstock, Vermont,” the largest plowing match in New England. (My personal best was second place.)

Marissa has had three pairs of Milking Shorthorns, but admits she would like to have a pair of Devons. Since the family just started a small herd of Devon cattle, I think her wish will come true.

When asked what she likes about the 4-H Working Steer Program Marissa said, “I like showmanship and going to fairs to see who is there. But it is a lot of work.”

Mark offers, “The kids get out of these steers what they put into them.”

I could not agree more.

Little has been written about working oxen in bygone days, probably because the daily occurrence was taken for granted. The tradition has been handed down through the generations in New England and lives today in the continuation of various competitions. Teamsters who compete in pulling contests have saved and maintained a unique cultural tradition of working oxen. Without these teamsters, oxen and the technology of effectively working them would have been lost in the United States. This valuable living tradition still inspires and challenges youngsters. It is my hope that these young teamsters will continue the tradition into the future.