Oxen have been an important part of human development for centuries. They still greatly outnumber horses and donkeys as beasts of burden, and the discussion of oxen as a backward way of farming continues today as it has for centuries. Horses are faster and tractors are more efficient where fuel is cheap and spare parts are available. But for the poor farmer who is far from able to afford either of these technologies, the ox continues to pull the plow. Oxen plug along tilling more soil than any other beast on earth. Their work is often accomplished in crude and uncomfortable yokes with poor training and accompanied by whipping and cussing.

Oxen are just one cog in the wheel of developing agricultural systems. Their use in agricultural development has many faces. It also has many different degrees of adoption, use, and interest. No single simple solution to agricultural development exists for the entire world.

It may seem farfetched that in some parts of the world, oxen are just now being adopted and put to work. In sub-Saharan Africa they have been used for only about 100 years. In Africa, the agricultural use of oxen is on the upswing. Many farmers there have never seen oxen at work; others remain skeptical about their use.

In Latin America, the use of oxen continues as it has in the past, often side by side with tractors and modern equipment. The great disparity between the rich and the poor means that farmers might work all week on a large farm driving tractor, only to return to their villages and use oxen or donkeys at home. In Cuba, oxen were readopted by farmers, in part by a government mandate, when the former Soviet Union collapsed in the late 1980s, and the farmers had to rely on locally produced agricultural power sources.

Similarly, in Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many farmers have reverted to animal power out of necessity. These farmers once had tractors and huge farms supported by the central government. Once they had to farm on small plots of their own, the use of oxen was an economic necessity rather than a step toward modern development.

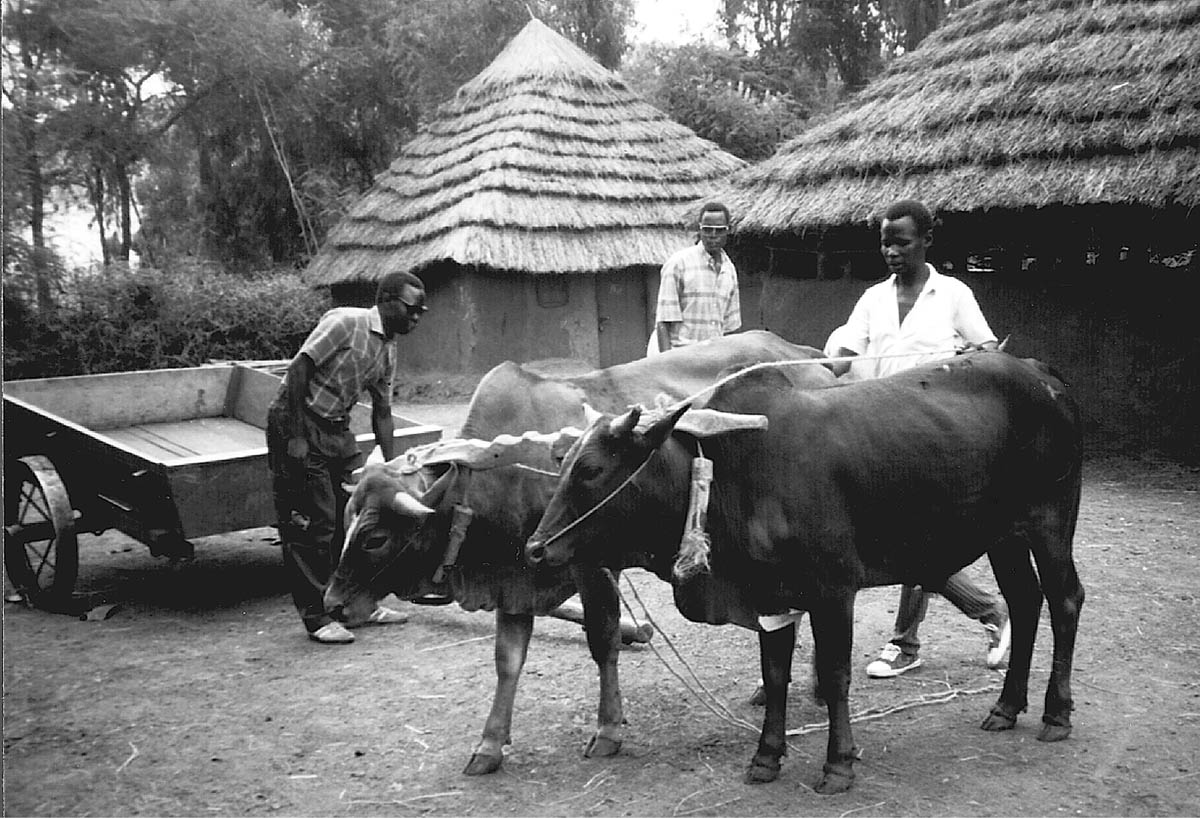

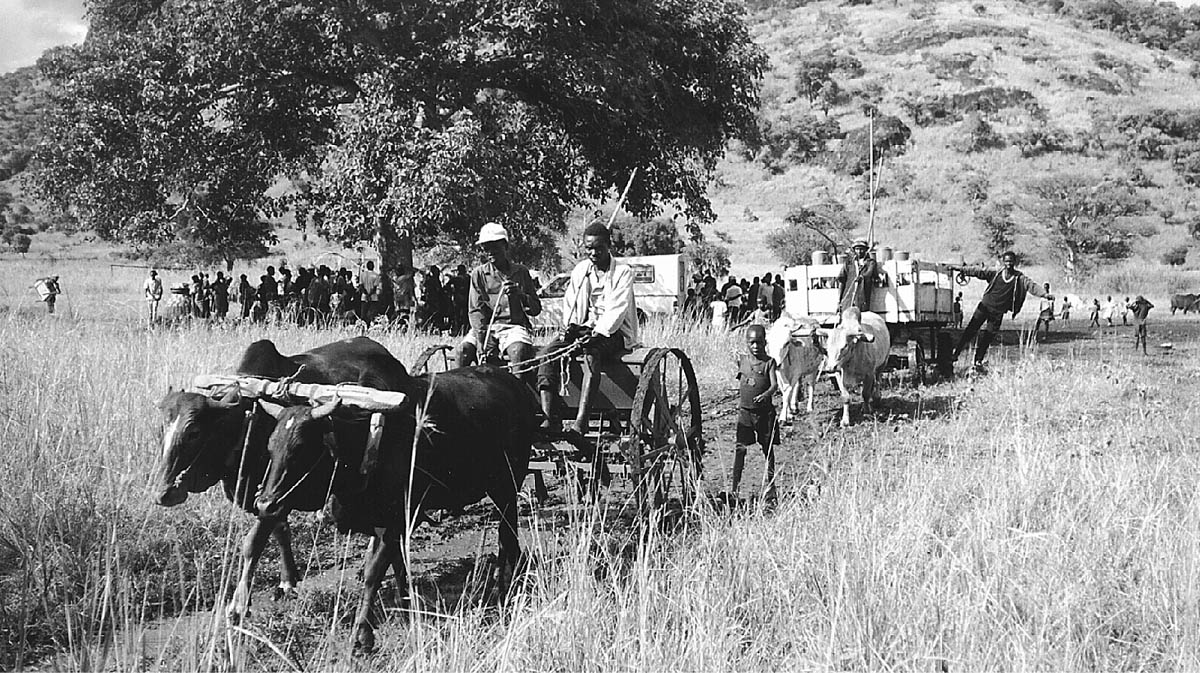

Oxen are used for transport and farm work in the rural areas of many developing countries.

The topic of oxen and animal power in international agricultural development is closely related to the use and history of oxen in the United States. The relevance may seem far removed from the needs of a farmer on the other side of the world who is struggling to feed his family. True, certain aspects may not be relevant to development workers and animal traction experts, but many of the methods for working oxen have remained unchanged for hundreds of years and can be used to generate new ideas or to perfect old ones.

The techniques for training and using oxen are similar everywhere. Most oxen are worked in pairs. When extra power is needed the pairs are hitched in tandem. The single ox is used in many areas, but not as commonly as oxen worked in pairs. Most oxen are used with a yoke. Although yoke designs differ, the comfort of the animal and maximizing his power are always a concern. The way oxen are trained to work in the yoke and pull a plow or cart is similar everywhere. All oxen must learn to stop and go on command, pull carts or farm implements, turn right and left, and back up, or at least position themselves to be hitched to a load.

When I have seen oxen at work in other nations, I have noticed many little things in the way animals are worked and handled that could be improved. Poverty and local culture influence the way the oxen are used, but the animals should be yoked comfortably to avoid sores and injuries. Training could also be improved. Such improvements in developing countries means someone has to encourage such change. My hope is that the ideas I have documented here will add a fresh perspective to the many works dedicated to the use of draft animals exclusively in developing nations.

The system of using and training oxen as seen in the United States is not beyond the means of the rural poor across the globe. Yokes, whips, and other tools that are used to work the ox are still locally manufactured with hand tools and technologies that are readily available everywhere. Techniques for training oxen are simple, straightforward, and easily adapted to other languages or cultures. The greatest challenge is sharing new ideas so as to encourage others to try them.

Introducing oxen into cultures that have not used cattle for work is easy where animals are readily available; teaching the importance of animal comfort and the use of improved yoking methods is often more difficult.

The New England tradition of driving oxen was imported from Europe and perfected over hundreds of years. Oxen were used for agriculture, logging, and transportation on many small farms in New England as late as the 1950s. They were usually the first animals on America’s colonial farms. They opened the way for agricultural development by helping to clear forests, cross the plains, plow tough prairie sods, and transport goods and people across North America.

As is true in other nations today, oxen in early America were the only animals appropriate for the job. They survived where other beasts would have perished. Working in their simple yokes, they accomplished every task necessary to build a nation out of the wilderness.

Training and yoking techniques used in the United States have been passed along from generation to generation, as they continue to be passed along today. Most Americans who keep oxen no longer use them exclusively for farm work, but the techniques they have successfully employed to train and work their cattle are the same as those used during the heyday of oxen in the development of the United States.

The technology for using oxen has not become stagnant in the United States as it has in other developed nations. Ox competitions have raised the level and expectations of animal training and use. Neck yokes and head yokes are pitted against one another in the pulling ring. The designs of each yoking system undergo cycles of experimentation, adoption, and use. Ox training and physical conditioning are often conducted as seriously as the physical training of human athletes.

The level of experimentation pushes ox teamsters in New England to do more and strive for better systems of training and harnessing the animals’ power. New England teamsters provide a variety of examples of working animals without the injuries and hazards that face both teamsters and oxen in developing nations.

Agricultural development arises from the ability to devise a “better” system of agricultural production. For many rural poor the world over, human labor is a major constraint to greater agricultural production. Plowing, weeding, and harvesting are activities for which oxen can easily fill the gap of labor needed. Greater efficiency and timeliness are easily accomplished when oxen are employed in agricultural operations.

Many farmers plow with oxen and then leave them idle for the remainder of the year. Employing the animals in labor-saving and profitable ways takes creativity, which in turn can make greater harvests possible. Acquiring the implements needed for plowing, weeding, and transportation may be a larger constraint than acquiring, training, and employing the animals.

Early American pioneers had to make or find appropriate farm implements. This same struggle exists today in many developing nations. Early America had little infrastructure of roads, communication, or marketing. While fighting wars against foreign nations, engaging in skirmishes with the natives, and weathering ups and downs in the market, the pioneers persisted. Most farmers were left to their own devices to grow successful crops. Often an ax, a plow, a simple sled, and a team of oxen were all they had to begin their farms.

Poor farmers around the world face daily challenges no less daunting. Many today are faced with far greater challenges. Tropical diseases, armed revolutions, shrinking agricultural lands, swelling human populations, and leaders who do not lead, all affect the ability of farmers struggling to produce meager crops against insurmountable odds. For them the ox continues to be of great economic and personal value.

Oxen are not the answer to all agricultural problems nor are they appropriate for all farmers. All users and potential users of oxen must understand both the limitations and the potential of draft animal power. Cattle are a burden. They require feed, water, and security from theft, large predators, and weather extremes. Buying an ox represents a substantial investment for a poor farmer. To lose an animal to disease or theft is a tremendous financial loss. Many farmers prefer hand labor to risking their few resources on a technology they do not understand.

If acreage is increased because animals are employed for plowing and planting, a severe labor bottleneck may occur during weeding. Increasing acreage is of little value if neither additional labor nor the employment of animals is added for weeding and harvesting. Oxen should generate a profit, not create more problems.

Oxen are appropriate where people are genuinely committed to using them. Without strong educational, moral, and technical support, cultures unfamiliar with cattle fail in training and using the animals. Even with such support, local capacity to maintain the technology must be encouraged from the beginning. People must be motivated to help each other train, work, and use their animals. Simply introducing this exciting “new” technology without follow-up inevitably results in failure.

Most successful technologies are passed down from generation to generation. The first time any new technology is introduced, its adoption is slow. Cultural bias, a history without draft animals, and the added burden of caring for livestock may be enough to halt the spread of draft animal use. Cattle can be a drain on the resources of a small farm where grazing land is limited or money is lacking for veterinary supplies. Oxen must be readily available and affordable. If they must be trucked in from long distances without ample replacements, their use in the long term may be unsuccessful.

Before the use of oxen is encouraged, an understanding of cattle must come first. Understanding the nature of cattle is the first step, before investing in expensive equipment, elaborate harnesses, and farm implements. All potential users of oxen must realize the animals’ limitations and the commitment necessary to make the technology work. The use of oxen can offer an increase in a farm’s productivity, but it requires a serious commitment to working the animals.

Training or using oxen involves no magic. Whether oxen are trained in Maine or Mozambique, the commitment to the animals, their training, and their comfort must be top priorities. The importation of animals and fancy equipment is unnecessary. If the local people have the capacity to use their indigenous breeds for oxen and have the interest in training them, the oxen will do the job. If local artisans are taught and motivated to manufacture low-cost yokes with the animals’ comfort in mind, the technology will spread.

Farmers who already use oxen may be the first to resist new ideas about improvements to training and yoking. Once they see the advantages of comfortable yokes and well-trained animals, they may be the first to quietly implement improved techniques. Few farmers will pass up an opportunity to learn how oxen can accomplish a variety of tasks on the farm in less time than hand labor.

Farmers who already use oxen may benefit from improvements in animal training and yoking.

Local breeds that are carefully selected, then conditioned and properly fed, often achieve what may or may not be achieved by importing exotic breeds and creating an artificial environment. Imported animals or “exotics” may fail miserably.

The breeds or varieties of cattle around the world have been developed over many centuries in specific environments. Although genetic improvements can always be made in any livestock population, don’t be too quick to dismiss a breed with which you are unfamiliar. The European breeds or other “humpless” breeds, for example, are often dismissed as work animals in certain African countries, where animals without humps are considered useless and unfit to work. Likewise the smaller local breeds might be dismissed by “outside” experts who have little knowledge of the local environment.

Although a particular breed might not be well suited to a specific local environment, there may be other reasons they are considered unfit to work. For example, certain types of cattle may not be preferred because they have no humps on their backs like the Zebu. In East Africa, cattle without humps cannot work as effectively with withers yokes, as they have been designed specifically for Zebu with large humps. European or other humpless breeds might be a better choice for other reasons, but because of the type of yoke used, animals without humps might be unfairly considered worthless. The imported breeds may also be more prone to local diseases or less adapted to feeding systems with limited water.

Ox training should be a sequence of events designed to produce animals that are trustworthy in the yoke and willing and able to do the work at hand. Because of local customs, not all oxen may be trained as young animals. Training older animals takes longer and is more complicated than training calves. Rushing through training and beating the animals rarely produces oxen that are eager to work.

A better method is to use a simple series of training exercises, beginning with handling the animals, and progressing to leading them and teaching them to start and stop. Then introduce the yoke and, over a period of weeks, slowly built up the oxen to heavy pulling or plowing. Training is made easier by yoking a young team behind an experienced team. While this step-by-step training may seem to some farmers to be a waste of time, the result is willing animals that are easy to work compared to animals that have been beaten into submission.

Training mature oxen to plow in one day might be an amazing feat that allows an “expert” to visit more villages in a given amount of time, and it can work if the oxen have had previous handling. But the next time they are put into the yoke their attitudes may be altogether different, especially if they are sore from plowing on the first day. In addition, if the animals have to be beaten so severely that they refuse to work or they lie down in the furrow, the new adopters of oxen may not be encouraged to try this new technology.

When viewing oxen around the world the temptation arises to criticize their yokes. No matter what type of yoke is used, the animals should never suffer due to poor design or fit. An extra few hours spent carving a comfortable yoke pays off in preventing animal breakdowns and injuries.

Every teamster must understand that animals with sores on their necks need an improved yoke design. Yokes that are designed so poorly that they make the animals constantly uncomfortable result not from poverty but from ignorance. Even the poorest person will go without shoes before wearing poorly-fitting shoes that cause wounds. Just as the athlete cannot run in shoes that do not fit, the ox should not wear a yoke that wounds him while he works.

Improvements like carving the yoke beam smooth and increasing its surface area to better fit the animal’s neck or withers will greatly increase animal comfort and prevent sores. A good yoke’s strength not only protects the animal from injury, but also saves time during plowing season and other critical periods.

A head yoke must comfortably fit the animal’s head and horns and be strapped in a manner that does not injure the animal. Wide straps work better than ropes, and a head pad on the forehead keeps the straps from chafing. The yoke should be designed to allow the animals to carry their heads at a level slightly lower than their backs. Animals with their heads held up high or down near the ground are uncomfortable and cannot perform properly in yoke.

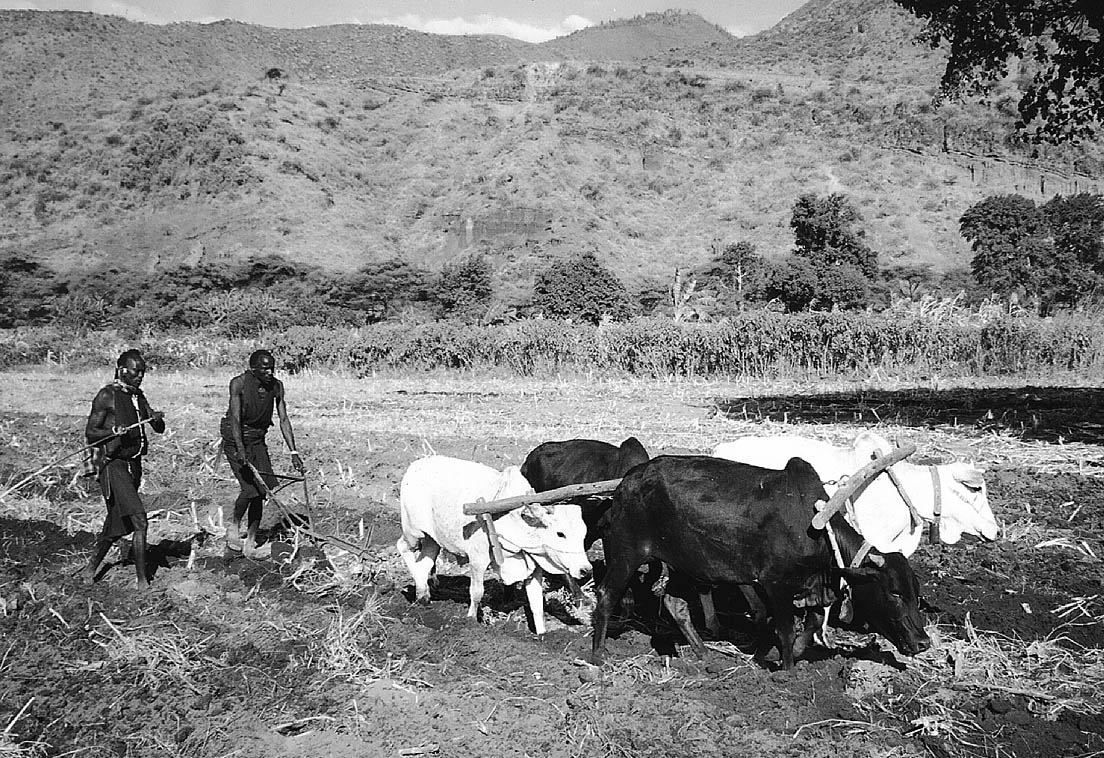

Many Maasai farmers in northern Tanzania are just beginning to adopt oxen and a more sedentary lifestyle. These people have traditionally been cattle herders. Growing crops and training oxen are relatively new to them. These poor but proud African farmers have nothing more than crude yokes, simple walking plows, and sleds, yet they do marvelous jobs with their oxen. The key to their success is that they know cattle and how to handle and work them. Their animals are well-fed and -cared for. Ox teams often have special grazing areas near the family compound. They are trained to do whatever work is asked of them, and they are physically conditioned for heavy work before going to the field.

The animals respond to verbal and visual cues, and the teamsters know what to expect from their animals. The result is beautifully plowed fields, no fussing or fighting with the animals, and farmers who are delighted with their work. The oxen wear simple rope nose baskets while weeding. Harvesting is accomplished using a sled and human labor. The technology is not modern, but it represents the beginning of a successful relationship between farmers and oxen.

Implements like a cultivator and cart may be added to the Maasai’s collection of tools, but for now the farmers are successful. Their crops are planted on time, they manage the weeding with animals, and harvest is much easier using animal power.

Compared to the option of hiring tractors for plowing, oxen are more affordable and represent a better long-term investment. After working for 4 to 5 years, the oxen are sold for beef at age 8 while in their prime. The farmers start young teams with the proceeds and recoup their initial investment with a little profit to boot.

The Maasai’s story highlights a group of farmers who had their animal traction priorities in order. They focused their efforts on the animals and the crops they were growing. They learned how to use oxen by watching other tribes using them. They didn’t need outside assistance and had never received training from extension officers or other development organizations. They were not persuaded to purchase fancy implements that sit idle for much of the year.

These farmers pride themselves on their cattle and their crops. Their only concern is the shortfalls of the yoking system they have adopted from neighboring tribes. They are interested in experimenting with new designs that do not cause wounds on their cattle’s necks. If all farmers using draft animal power could be so motivated, draft animal power would spread easily to new areas.

Traditionally nomadic cattle herders, the Maasai are beginning to adopt oxen as they learn to grow crops.

Potential pitfalls and alternative agendas exist with any method of introducing oxen power for agriculture. The best approach is one that uses a variety of techniques over a long period of time and takes a coordinated effort. Employing a variety of techniques across a region may also be useful for testing the impact of different forms of education. The following are some of the many approaches to introducing oxen and improving their use to farmers in developing nations.

Some ox training or animal traction programs introduce the technology through the use of extension officers who are familiar with the local people, their customs, and their crops. Extension officers save time because they understand the local language and culture. They must understand the technology and be willing to demonstrate their expertise.

The impact of extension education is short-lived without continuous support and financial aid, which may be a disadvantage if farmers rely solely on extension officers. Sometimes development agencies or animal training experts work with extension officers to help provide longer-term commitment to projects. Most extension officers are responsible for a large area with many farmers. Technical assistance and financial support can help them do a better job of introducing a new technology.

Ox training and animal traction training programs, such as this meeting in Uganda, are popular in many areas where oxen and other draft animals have not previously been used.

Men are most likely to participate in programs that focus on animal traction. As women and children are exposed to the technology, the adoption and use of oxen in their area generally has a greater impact.

Since communication in rural communities can be a serious problem, farmers learn best by example. The best form of education is one that has been identified by the farmers themselves as necessary and in which they can actively participate at every level. This “bottom-up” approach may be difficult to administer and maintain, but the farmers will benefit greatly in the long term.

Using farmer support groups and successful farmers as models and mentors requires the organizational skills of and effort by the person introducing the technology. This approach works best if the organizer spends a long time in an area and wants to have an impact on the local farm community. Working directly with farmers to generate ideas and address their concerns is a great way to share and transfer information.

Some successful animal traction programs are initiated by farmers and run through the use of cooperatives or farmers’ groups. These cooperatives and groups are supported by the farmers, the government, foreign development agencies, or companies that may benefit from greater harvests by purchasing crops or selling inputs such as seed, fertilizer, and agricultural chemicals.

With funding, support, and influence from outside the local community, some agencies or companies may have specific concerns or desires. These must be understood and addressed beforehand, especially in countries without strong agricultural leadership.

Vocational schools provide hands-on experience and help vocational students learn alternative ways of farming. Many vocational schools have fields and plots where the students work. Students are usually eager to try anything that will ease the manual labor they must do in the field. In vocational schools, high standards of animal training and use can be achieved because students work for months to perfect their ox yokes, training techniques, and the oxen they use. While vocational students are usually willing to learn new techniques, they sometimes become frustrated when they return home and find no support for their new ideas.

Agricultural shows at a national or regional level provide a good place to see how area farmers react to the idea of ox power by providing hands-on demonstrations and discussions. Such shows also challenge farmers to view new systems of training and yoking oxen. Large corporations that sell products or merchandise to farmers may be enticed to support either the entire show or training programs, demonstrations, and other events at the show.

Competitions where farmers are invited to bring their ox teams for plowing contests, ox pulling, and ox cart competitions generate interest and challenge teamsters to improve their techniques. Farmers are usually persuaded to come when prizes are offered. Farmers who do not bring their own teams may learn by watching others and seeing their successes or failures. When a successful event spawns subsequent events, changes and new ideas follow. Historically this has been done in North America, and even with Cuba’s recent reintroduction to oxen, as mandated by the government, ox competitions have flourished as a way to spread the technology and encourage innovations.

Research institutions often provide sites for testing new ideas and techniques in a controlled environment. Demonstration plots or farms may be used as tools to demonstrate what may be accomplished under ideal conditions. While such demonstrations may generate interest among farmers, the impact will be greater if the demonstrations are located in local villages or other visible areas. The animals and the crops at research institutions are also often in better condition than would be found in the villages, and farmers may point out that the labor and input does not reflect the reality on their farms.

Television, radio, and local billboards may be used to introduce technology and help farmers become interested in using oxen. These media may not directly address the needs and concerns of the farmers, but instead may provide the impetus for making informed decisions before farmers decide to use oxen in their operations.

Many cultures have had cattle for decades but never realized the potential of using the animals for draft power. Ox power technology may be introduced in many ways. Forcing or persuading people to use a technology that is not appropriate is doomed to failure. The key to success is to first interest farmers in using oxen.

I first met Paul Starkey, from Reading, England, when he visited the United States in 1991. He said he was a consultant who worked around the world with oxen and wanted to meet with me. I was delighted to make the acquaintance.

Over the course of his two-day visit, I was his guide to numerous New England fairs, including Fryeburg Fair in Maine. At the time we engaged in the most thought-provoking dialogue I had ever had on oxen.

His experience included traveling to more than 100 countries around the world, where his work with animal traction (draft animal power) focused largely on the use of oxen. At the time, I remember realizing how little I knew about oxen, outside of my focused perspective on using them in living history farms or in competition at agricultural fairs.

Paul’s visit inspired me to learn more about oxen outside the United States. His photos and ideas mesmerized me and inspired me later to travel to Africa. I must admit, looking back, that my meeting with Paul largely inspired my Ph.D. research on the use of oxen by the Maasai people in Tanzania, who historically are pastoralists, and who only recently adopted the use of oxen in growing agricultural crops.

As I did my preliminary research, Paul’s many books, conference proceedings, and articles became critical to understanding the use of oxen by the world’s poor. When I contacted Paul in 1996, before traveling to Tanzania to begin my field work, he also became a resource, helping me make connections with people doing research and extension work in East Africa.

Since that first meeting, Paul has continued to stay in touch annually with his unique photo Christmas cards portraying oxen at work in different countries that he has visited. We met in 2002 in Uganda at a conference called Modernising Agriculture: Visions and Technologies for Animal Traction and Conservation Agriculture. We then traveled together to meet some farmers and extension people doing great work with oxen in Uganda.

We met again in 2004, when I visited England and Paul was my host, to present a paper on Ox Yokes:Culture, Comfort and Animal Welfare at a conference in England (see: www.taws.org/TAWSworkshop 2004.htm). It was exciting to meet his family, who were all global travelers, and see his amazing collection of ox yokes, equipment, and books on oxen. A Christmas card showing oxen in Cuba and our discussion about that country that spring inspired me to travel there later in 2004.

Paul Starkey continues to be an inspiration to me with his work overseas related to animal traction. His travels, tales, experiences, and adventures related to oxen probably make him the most experienced person globally with regard to using oxen. He is certainly the most prolific writer on the subject, and most of his work can be found on his Web site: www.animaltraction.com.

Oxen are not the answer for all people who are trying to make improvements in their agricultural systems. Some cultures have an aversion to keeping animals or have geographic and biological concerns that may make keeping cattle difficult or risky. For those who wish to improve their ability to plant, harvest, and transport crops and forest products, however, oxen may be ideal.