Whether you are selecting your first or your fiftieth team of steers to train as oxen, your preference as to breed and type, as well as your plans for how the animals will be worked, will and should influence your choice. Although your preferences are important, you would be wise if you are a novice to seek the advice of experienced teamsters when choosing one steer over another. You want the time and money you invest in these steers to result in pride, rather than disappointment.

An ox is not a separate species or breed, but simply a castrated bull used for work. While many examples from around the world display or describe both cows and bulls being used as draft animals, castrated male cattle are most often employed as work animals.

The castration of a bull at an early age changes his growth pattern. A growing steer will develop longer legs and a larger frame. Thus the ox grows taller and heavier than the bull of the same breed when he is castrated before he matures. With castration and the loss of the influence of the hormone testosterone, the steer is also more placid and more easily controlled than the bull. Although castration causes a loss of muscle mass, particularly in the neck and shoulders, the greater size, length of leg, and more agreeable attitude of the ox make him a steadier and more desirable work animal. Castration, particularly on a small calf, also influences horn size and head shape, giving the ox a more cow-like appearance.

The two existing species of cattle, both used for work, belong to the genus Bos. They are Bos indicus (the Zebu, or humped breeds) and Bos taurus, representing breeds of European or Asian descent that have no humps. Bos indicus is common in warmer climates, while Bos taurus is more common in temperate and cool climates. For use as oxen, the two species are often crossbred by farmers in some areas to combine traits both species possess.

The ideal ox is large, strong, straight, and healthy.

A third, now extinct, species was the Bos primigenius or auroch (also called urus), a huge wild animal thought to be similar in size to the modern Italian Chianina. The domestication of such an animal represents a great milestone in human history. The auroch is thought to have been a predecessor of, or at least had a great genetic influence on, early domesticated cattle. The auroch became extinct during the early seventeenth century. The last known survivor died in captivity in Eastern Europe.

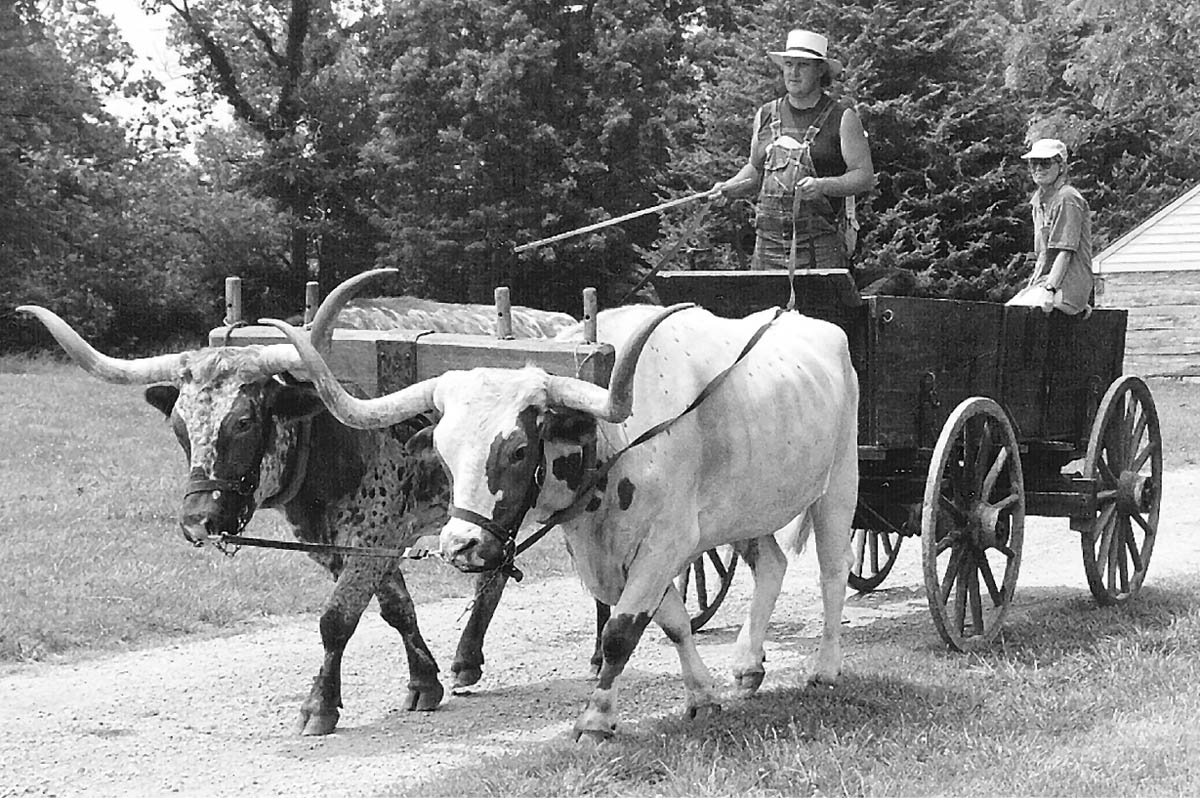

Oxen are normally worked in teams of two, with pairs sometimes hitched together for additional power. Multiple pairs form teams used for logging, heavy transport, and plowing dense soils. Teams are hitched together in tandem, one pair after the other. Out of necessity, often where farmers have few resources, oxen have been hitched together with other species, such as the horse or donkey. Even the poorest farmers, however, admit that multiple-species hitches are not a desirable situation.

Selecting steers to train as oxen is much like selecting any animals to be used for work or production. Before choosing an animal you must have a standard by which to evaluate the animal. No set standard has been established for conformation of the ideal ox, but most teamsters agree that an ox should be healthy, well muscled, and sound on his feet and legs, and have an agreeable disposition. A well-matched team of carefully selected and trained animals, with good conformation, is a joy to work. Such animals can be expected to live for many years and may be used for a variety of tasks on a farm or in the forest.

Oxen are generally easier to train and work as a pair or team. Selecting a team, however, is more challenging than finding one good animal. Putting together a team involves finding two or more animals that match not only in color but, more importantly, in disposition, agility, and size. Few perfect teams exist. Minor differences between animals are hard to avoid. Teamsters do the best job they can of matching or “mating” (putting together or breeding cows to bear calves that will grow, develop, and act alike) their teams.

An ideal mature ox may never be seen or found, but it is always something to strive for in selecting animals. Understanding conformation and knowing what to evaluate is an important part of the selection process. Great differences exist between breeds and types of cattle. Take these differences into account in evaluating your animals for work. A breed like the N’Dama, a tiny West African animal, will have a different standard size and temperament than the giant Chianina, developed in Italy under much different conditions.

Before trying to put together a team, have a mental picture of what an ideal ox looks like. A good judge of livestock starts with a breed standard or scorecard. As no set standard has been developed for judging or evaluating the ox, you have to learn what to look for. Most experienced teamsters agree that an ox should be able to perform the duties expected of him for many years with a minimal amount of difficulty or hardship. Certain characteristics of the body are therefore essential. (See box, below.)

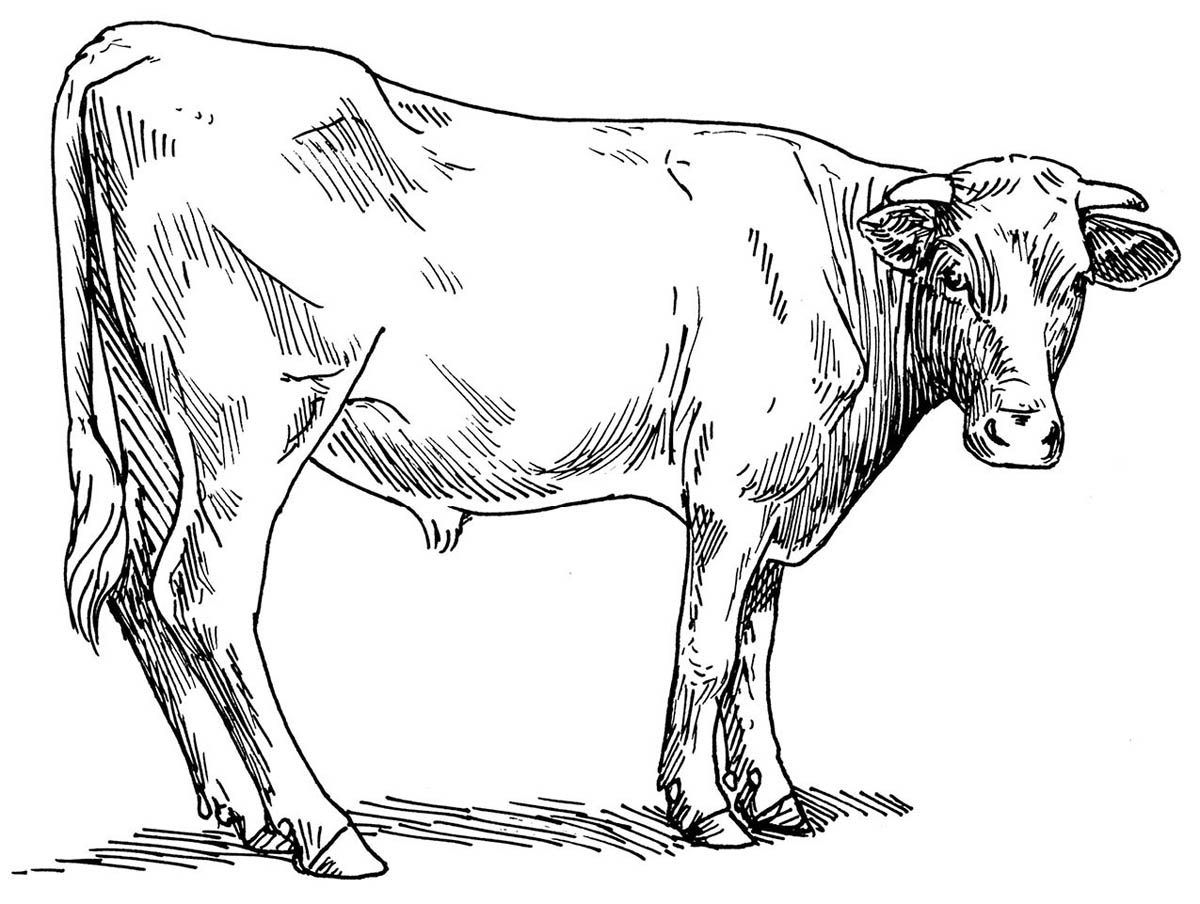

The ideal ox is large for his breed, and he stands on a strong and relatively straight set of front and rear legs when viewed from the front, rear or side. The animal is not too cow-hocked, post-legged, or sickle-hocked. His hooves are dark, short in the toe, high in the heel and wide, but not to the extreme. His feet and legs track forward in a straight line. His neck, shoulders, back, rump, and thighs are heavily muscled. Working cattle transfer most of their energy from their rear legs, which push forward, to the shoulders or neck and head, depending on the type of yoke. To easily transfer this energy, the body, chest, and rump must be wide and strong. Every animal used for work should show the desirable degree of thickness for his breed.

Other essential traits include the following:

Pass over steers that lack any of these essential characteristics. You will spend a great amount of time and energy training your team, and training inferior animals does not often yield desirable oxen. Characteristics such as color, breed, and how well the animals match are much less important than their ability to perform in the yoke.

While you might argue that animals lacking some of the listed characteristics could make fine work animals, good conformation helps ensure that your animals will not develop problems during their years of hard work. Animals lacking perfect conformation may work successfully, but poor conformation or health problems eventually catch up with them.

A post-legged ox’s hind legs are too straight, as in the lower drawing. The upper drawing shows good leg conformation.

This Chianina has desirable feet and legs in both the front and rear.

This steer toes out in the rear and has hocks that are pointed together slightly — called cow-hocked.

This Milking Shorthorn has severely sickle-hocked rear legs.

As an ox teamster, have specific goals in mind for your team. How will you use the animals? Will you use the team for show, pulling, or farm work? Suitability to the type of work will greatly affect your choice of animals.

Pulling oxen and oxen used for farm work alone do not have to match in color or horn shape. The focus is work; therefore, the temperament and the ability of the two animals to work together effectively under a heavy load is more important than matching perfectly as a team.

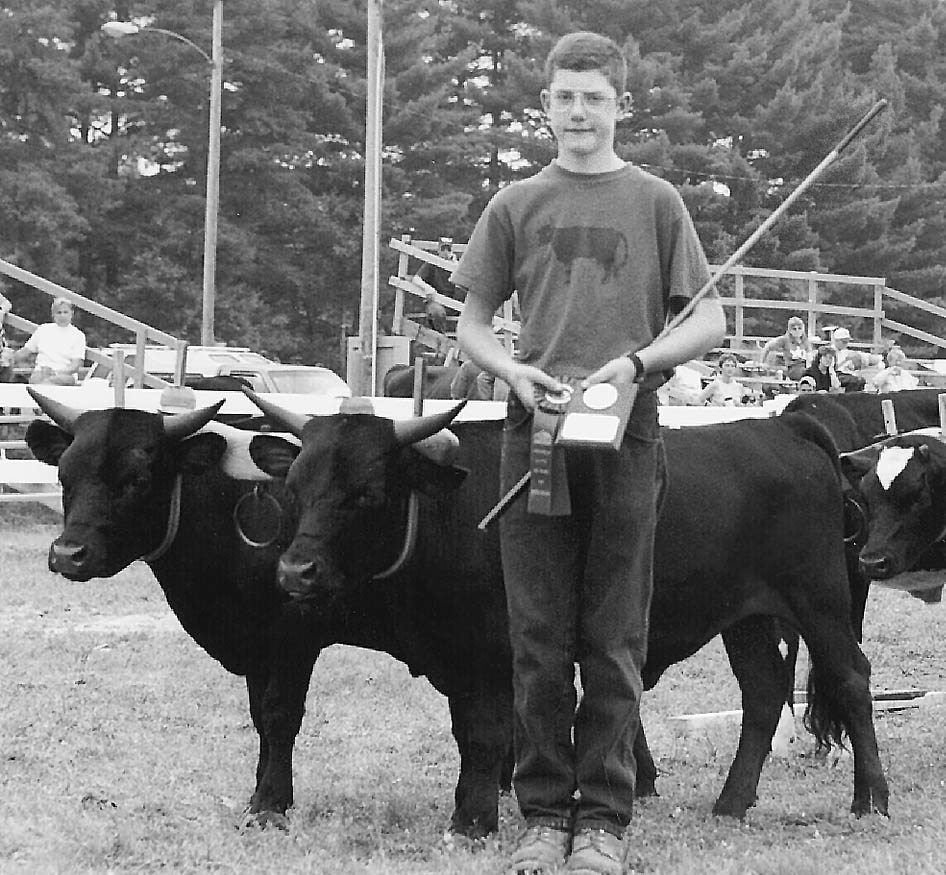

A show team should be calm and obedient, but also well matched and flashy with an appearance that catches the judge’s eye in competition. Most oxen used for show are well matched in body, head, horns, and bone structure. They often carry more flesh than teams used for pulling or work.

A pulling team used in competition or logging needs to be active in the yoke, free of major conformation problems and, most important, have the mentality and willingness to pull aggressively as a team. They should be well muscled in the legs, neck, back, and chest. Their legs should be relatively straight and their top lines straight and strong. Due to their appearance or character, many of the best ox teams in pulling contests or woodlots would never place high in the show ring. A hard-working ox doesn’t have to be attractive.

A farm team need not look sharp or have the willingness to push their physical limits. However, the basic selection criteria for sound oxen still apply. Although well-matched animals won’t necessarily work any better for you, they will be more valuable if you decide to sell them.

A farm team need not be flashy like a show team, nor pull aggressively like a competition team, but must be willing to work, and should match in case you sell them.

The beginning teamster wishing to work with horses is advised to start with an older, well-trained draft team. By contrast, the beginning ox teamster can easily train his or her first team of calves. Both team and teamster learn as they go. New England 4-Hers as young as eight or nine years old train their own calf teams with tremendous success. A well-trained team that is two or three years old can be just as calm and easy to work as an older team.

Selecting calves allows the teamster to mold the animals’ sizes, shapes, and personalities. While the ability to mold the team is not foolproof, a teamster with control over the team’s feed, handling, and environment will have a greater impact on how the animals mature in the yoke than a teamster who lets his calves run with a herd of cattle.

A team of oxen is made, not born.

A team of oxen is made, not born. It is the result of many hours of handling, training, and careful attention to feed and environment. Some teamsters buy four calves and start two teams, so they can later choose the best two animals for their team, selling the two animals that don’t match or work as well.

Some teamsters prefer to let someone else do the raising, matching, and training, then choose the best available animals to meet their needs. This method is more foolproof than buying calves, because older animals are less likely to change in personality or size. The challenge is that oxen are not as common as they once were. In some countries where draft cattle are more common, the only animals sold are culls. Most good stockmen never sell their best animals.

Oxen live only 10 to 15 years. As an ox teamster once said, “. . . just about the time you get the team broke just right, they up and die on you.” Many teamsters who have good teams and use them daily do not cull their animals. You may therefore have a hard time finding a mature, well-trained team for sale at a reasonable price.

Selecting untrained animals at maturity is a good way to know exactly what kind of animals you are getting. Training them will be more challenging, but you do not have to wait for them to grow up to be put to work, nor must you wait to see what they will look like. I have purchased calves that matched perfectly, only to have the two animals grow up to be different colors with different conformations and dispositions. Eventually I had to buy new mates for each of the already-trained steers.

Choosing a team as mature or older animals is typical in many developing countries, where cattle are not large and they are handled daily while being herded to and from grazing areas. Teams are put together and almost immediately trained and put to work. The system works well because the animals are accustomed to people and are small enough to be muscled around, if necessary. The system is not as effective in the United States and Europe, where cattle can weigh more than a ton and may never have been touched prior to training.

Whenever breeds of cattle are discussed for use as oxen, debate and differences of opinion ensue. With so many breeds of cattle to choose from, opinions are endless. It is clear that no one breed is best for all purposes. My own breed of choice has changed several times over the years as my level of experience, age, and needs have changed.

For example, I admire and have trained numerous Devon teams for their speed, stamina, and attitude, but other breeds are calmer and easier to work with. The Devon breed has proved to be too much for my children, who want to work casually with my team. The Devon has also proved to be difficult for other novice teamsters, in ox-training workshops.

An important question to ask early in the selection process is whether or not the breed you desire is available in your region. You might choose a breed fitting all your needs, but the nearest herd or team is 2,000 miles away. Are you willing to spend the money or time necessary to acquire such a team? Is the importation of an exotic breed really the best choice? Often more common breeds or local strains are better adapted to local environments and diseases, an especially important consideration in developing countries.

When choosing calves, select animals from similar bloodlines. They are more likely to remain matched when mature. Important factors in selecting a team include:

Disposition involves an animal’s attitude toward being in a yoke and following commands. Some cattle are easy and placid in the yoke; others are high-strung and need constant attention. In selecting a team, make sure you have animals that work well together. Slight differences in disposition that need to be worked out always exist, but an aggressive or nasty steer yoked with one that is friendly and calm is not a pleasant experience, especially if the steers constantly fight each other in the way they move in the yoke.

Occasionally a well-trained steer is used effectively in training a wild one. Historically, this practice was common in logging camps and freight companies. Today most oxen in the United States have been trained from an early age.

Some cattle are more alert and spirited than others. Don’t yoke two animals that are opposite in agility. A fast steer and a slow one won’t make a good team for show, farmwork, or pulling. In both cases one steer is always ahead of the other, limiting the team’s effectiveness. Ox teamsters around the world struggle with two animals that are not matched in their willingness to work as a team.

Two steers that are different in size may work effectively in the yoke, provided they have a similar disposition and agility level. Similar size is important for a show team, as differences may affect the judge’s placing. Keeping two steers exactly the same size by altering their feeding program can prove difficult, especially if they are purchased as calves.

While modern ox yokes can accommodate a small steer and a large one, a great deal of experience is needed to make and adjust a yoke to deal with animals of different sizes.

Many ox shows and judges consider how well a team matches and the animals’ overall conformation. Slight differences in conformation are not usually a problem in a working team, but all other things being equal, an unevenly matched show team will not place as well. A team used for show and exhibition should be matched in body conformation. You can fairly easily put one animal on a diet to maintain his weight, but you will have a harder time changing his frame and overall size.

The way the team walks, stands, and moves is sometimes a function of conformation. It is not critical that the animals match perfectly in conformation, but vast differences can affect the team’s appearance and sometimes overall value. Many experienced teamsters strive for heavy-boned, lean cattle with large feet and a steep hoof angle (short toes and high heels) because such animals supposedly live longer and have fewer health problems.

Often one of the most sought-after characteristics in selecting cattle, color may give you some indication of the animals’ breed and bloodlines, but it remains one of the least important traits for a working team. A team that is well matched in color is attractive, but if the animals are not similar in disposition, agility, size, and conformation, problems arise as the animals are put to work.

In developed countries, many breeds of cattle originally selected for size and strength in the yoke have been intensively bred for meat or milk production. Where once the speed, working ability, and adaptability of cattle were valued as desirable characteristics, modern breeds have been selected to fit neatly into categories and systems of intensive modern cattle management.

Beef cattle have been selected for maximum growth and the ability to fatten quickly and easily, while other attributes important to an animal used for work have been neglected. Such characteristics often include sound feet and legs, athletic ability, and tractability. Beef calves are hard to find in the northeastern United States. They may be more expensive to purchase and more difficult to train than dairy breeds, largely because of their lack of human contact and regular handling at a young age. The beef breeds are thick and heavily muscled, and as oxen they may be difficult to keep lean for pulling competitions based on weight. In Nova Scotia, however, beef breeds such as the Hereford and its crosses are commonly used. Many of these fine animals are brought to New England to compete in pulling contests and easily beat leaner dairy-type cattle.

Dairy cattle have experienced a greater degree of specialization than have the beef breeds. Shorthorns, Brown Swiss, and Ayrshires were once bred as triple-purpose animals to provide work, meat, and milk. Many of the historical qualities like hardiness, muscling, and soundness have been forfeited in the name of high milk production. This fault lies not with the breeds or breeders, but with their attempt to survive in a world of specialization and maximum efficiency. As oxen, dairy breeds and their crosses are generally more popular than beef breeds in New England, largely because of tradition. Compared to beef breeds, dairy calves may be purchased younger, trained more easily, and molded into exactly what the teamster wants.

Dual-purpose breeds have retained more of the original characteristics desired by ox teamsters, but in many regions their numbers have fallen rapidly. The American Milking Devon is a classic example. This breed was once one of the most sought-after animals in New England. In 1880 J. Russell Manning, a veterinarian and author, wrote about the great attributes of the Devon: “As workers, milkers, and beef makers combined, for the amount of food taken in they have no superior.”

In the United States and Western Europe the survival of any breed has been based on its ability to adapt to drastically changing markets and methods of management. Many cattle breeds originally began as triple-purpose animals, but the draft characteristics that once were common are now difficult if not impossible to find. A smart, active, and athletic animal does not pay the bills.

Today the American Milking Devon is one of the only breeds in the United States in which breeders have actively tried to maintain draft characteristics. Consequently, this breed is now rare. It cannot compete with the Holstein or Jersey in efficient milk production, nor can it compete with its close cousin the Beef Devon or with the Charolais in the feedlot, where the only measurement of success is a larger, faster-growing, and more heavily muscled animal.

More than 50 breeds of cattle are found in the United States and more than 1,000 breeds in the world. While certain breeds may appear similar to one another, their temperament, color, or other characteristics vary. All cattle can be trained to work. All have their own individual personalities, yet breed can greatly influence temperament and speed. Some teams need more work than others in order to maintain their attention and control.

When choosing a breed, consider the type of environment in which the animals will be worked. Some breeds are better suited to certain climates or environments. Choosing a beautiful team that cannot endure the heat, insects, or local diseases will affect the team’s working ability.

Animals used in hot climates, for example, need to be suited to such weather. Zebu or Bos indicus–type cattle are better suited to warm climates. They will work harder and faster than European or Bos taurus–type animals exposed to the same degree of heat and humidity.

The opposite holds true in cold climates. A team used in logging operations in northern areas must be acclimated to such conditions. Many Zebu animals, with their loose skin, short hair, and ability to endure heat will suffer greatly in subzero weather.

In areas where trypanomiasis and other tick- or insect-borne diseases are endemic, certain breeds of cattle are unable to survive. Native breeds with some natural resistance are often preferred in developing countries, even though larger, stronger animals might be available.

Most teamsters have a favorite breed. Others seek out characteristics they claim are just as important as conformation or temperament. Some teamsters never yoke a steer with a black nose or white feet. Although characteristics like skin or hair color may affect an animal’s ability to work in direct sun, some of these “rules” have no bearing on an animal’s ability to work.

Don’t believe everything you hear until you have had the opportunity to see numerous breeds in the yoke. When you find a breed you are interested in, ask the breeder how easily they train to a halter or how well behaved they are when captured. Usually individuals within a breed behave in a similar manner on a halter and in a yoke.

Temperament is a heritable trait passed down the generations. Beware that some lines or families within a breed can be more difficult to work with.

All animals are easier to work with if they have been frequently handled and acclimated to people. When possible, watch how representatives of the breed behave in the yoke after they have been properly trained. Opinions are sometimes based on the teamster’s ability and not on the animals’ characteristics. While some breeds are more challenging than others to train, many teamsters agree that the breed doesn’t matter as much as the teamster’s experience and time spent working with the animals.

The most common breeds used as oxen in New England include the Holstein, Milking Shorthorn, Brown Swiss, Chianina, Jersey, and Milking Devon. Also to be found are teams of Ayrshires, Dutch Belted, Charolais, Longhorns, Herefords, and Dexters.

Milking Shorthorns and Holsteins are considered excellent breeds for the beginning teamster because of their even temperament and lower purchase price compared to other breeds. Dairy calves have the additional advantage of being handled often and bottle- or bucket-fed, which makes training easier. Modern dairy breeds tend to be leaner and more angular than those of the past, but the mature ox usually fills out and puts on muscle if given the opportunity. Many experienced teamsters will yoke nothing but a Holstein or Milking Shorthorn.

The unique characteristics of breeds such as Chianina, Dutch Belted, and Milking Devon make them desirable as oxen, but these breeds are hard to find. They are more expensive than more common bull calves that can be purchased from a local dairy farm. Many other breeds may catch your eye but may not necessarily suit your needs as a teamster. Just because you are impressed by a pair of giant Chianinas or a pair of snappy Milking Devons, don’t be fooled into believing you will be less satisfied with oxen of a more common breed.

When a certain breed is not available in your area you might convince someone to breed some cows to a bull of that type, if you provide the semen. Shipping semen across country is a lot cheaper than shipping live cattle the same distance. Artificial insemination has produced many crosses without a major financial commitment or risk to the breeder.

A teamster in Maine had a pair of Devons that were sharp-looking and fast. They never slowed down. Every time they were hitched they wanted to trot away with the load, and did so more than once without the teamster — all the way back to the barn. This teamster tried a neighbor’s Guernsey team, which were not as fancy or as heavily muscled. After a calm relaxing morning hauling firewood, he decided to invite the neighbor over to help him haul out his firewood with the Guernseys, while the Devons stayed in the barn.

Many teamsters prefer crossbreeds because they combine the best characteristics desired in a draft animal, including soundness, longevity, and hybrid vigor. These crosses work well since neither milk production nor maximum growth is an important selection factor. Even multiple crosses or “mongrel” cattle make terrific work animals, because they tend to be more like their early predecessors. The challenge in selecting such animals is finding a suitable teammate.

Far too many breeds exist to cover them all here, so I’ll discuss only the breeds most commonly used as oxen. Numerous books are available (some listed in this book’s appendix) that describe the characteristics of cattle breeds around the world. While the following descriptions offer a general guide in choosing a breed appropriate for your needs as a teamster, hundreds of other breeds are used equally successfully as work animals. When the training is done, any team with good conformation is impressive, no matter what the breed.

Every team is the result of hundreds of hours of training and work. Any breed of cattle may be trained. Given an equal number of hours in the yoke, some are easier to work with. They would receive a 1 to 3 on the tractability scale. The more challenging breeds (rated 7 and up) may have traits that are desirable for specific purposes, such as pulling competitions. Such breeds are preferred by teamsters who seek their special characteristics and have the skills to handle the animals. A great deal of genetic variability exists among the various breeds. The wide variability in size and temperament means a breed is out there to meet the need of any ox teamster.

See Appendix I for a chart comparing ox breeds.

Origin |

Scotland |

|

Color |

brownish, red, and white |

|

Mature Weight |

2,000 lbs. (900 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

active and alert |

|

Tractability |

7 |

|

Other |

attractive long horns |

The Ayrshire has red and white patches and distinctive horns.

Noted for its long horns that grow out, then tilt upward and backward, this medium-sized dairy breed originated in Scotland in the county of Ayr. The mature Ayrshire ox in good working condition matures to nearly 2,000 pounds. Ayrshires are reddish brown and white and can come in any combination of those two colors, including almost all white to brindle.

Like other breeds developed in Scotland, Ayrshire cattle tend to be active and aggressive on pasture, and they are noted for their great ability to thrive on poor pasture. In the yoke they train easily as calves, but they may be challenging if allowed to have their freedom for the first few months of life.

Origin |

Switzerland |

|

Color |

light to dark brown |

|

Mature Weight |

2,400 lbs. (1,090 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

large |

|

Temperament |

docile and slow moving |

|

Tractability |

2 |

|

Other |

grows rapidly |

The Brown Swiss is a large, calm, slower-moving breed.

This large breed grows fast and carries more flesh than other dairy breeds. It was originally bred for size, ruggedness, and sound feet and legs, characteristics that persist today. The Brown Swiss is noted for its docility, slow (sometimes poky) nature, and late maturity.

Teamsters who are accustomed to other breeds may find this breed to be temperamental, sensitive, and difficult to work. Temperament should not be confused, however, with an inability to work. Many Brown Swiss teams are excellent work animals for the field, forest, show ring, or pulling competition. In fact, in many Latin American countries, Brown Swiss cattle are sought after and often crossed with Zebu animals.

The Brown Swiss has unique coloring: solid brown that may vary from light grayish brown to almost black. Bulls are generally dark, and the longer bull calves remain intact, the darker they usually become. They always have a black nose, tongue, tail switch, and hooves, and a unique white ring around the muzzle.

The calves are generally large and grow quickly. Calves are sensitive and may require extra care for the first few weeks, especially if they are bucket-fed and not allowed to nurse from a nipple pail or cow.

In New England, Brown Swiss are used in heavy pulling classes because of their large size. Mature animals weighing up to 2,500 pounds are common. Due to its docile nature and slow pace, this breed is popular among youngsters, although the fast-growing calves soon tower above their young teamsters.

Origin |

France |

|

Color |

white |

|

Mature Weight |

2,300 lbs. (1,045 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

large |

|

Temperament |

moderately alert and active |

|

Tractability |

6 |

|

Other |

heavily muscled |

The Charolais is a large breed that has been used for centuries as oxen in France.

Mature animals of this large white beef breed are large framed and heavily muscled, making them fine draft animals. The calves are sometimes hard to find. This was once the draft breed of choice in France, but the number of Charolais cattle used as draft animals in New England is low. The Charolais is often crossbred with the Holstein to get a light brown or tan, almost khaki-colored, animal.

Origin |

Italy |

|

Color |

white |

|

Mature Weight |

3,000 lbs. (1,365 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

huge |

|

Temperament |

alert and excitable, at times to a fault |

|

Tractability |

10 |

|

Other |

grows rapidly |

The Chianina is the largest breed of cattle in the United States. The all-white, horned cattle are the original Italian type.

Developed as a large draft animal in the Chiana Valley of central Italy, this is the largest breed of cattle in the world. Mature steers are often 6 feet tall at the withers and weigh up to 3,500 pounds. Beautiful spans of Chianina oxen can still be found in rural Italy today. They are fast growing and especially long legged. Of all the breeds, they have one of the most athletic appearances.

The true Italian Chianina is all white with large horns and a black nose, tail switch, and tongue. The breed is noted for its strong feet and legs and for its longevity.

In the United States, many registered Chianina cattle are black or dark brown and polled. Such animals are American adaptations, largely the result of an open breed herdbook. The goal in crossbreeding was to yield more desirable carcass and feedlot traits. This has created an animal different from the Italian Chianina, originally developed to be one of the world’s largest, most athletic, and powerful breeds.

The Chianina is popular among teamsters in New England interested in entering pulling competitions. These animals tower above their Holstein, Shorthorn, and Brown Swiss counterparts and at maturity usually win pulling competitions because of their sheer size. In weight classes they also have a higher ratio of muscle and bone compared to gut. In fact, their shape has been compared to a greyhound dog, allowing them to be larger animals in the same weight class.

Since they tend to be more high-strung and excitable than the Holstein, Shorthorn, or Brown Swiss, take care to properly train these animals when they are calves. This extra care is especially necessary when training calves that nurse their dam and are given free run of the pasture. Frequent tying and handling of the calves will pay great dividends.

For use as oxen, the Chianina is commonly crossed with the Holstein, Brown Swiss, or Shorthorn. Most often the Chianina is used as the sire, crossed with large dairy cows to get calves with the slower growth pattern and low-key temperament of their dam. Compared to full-blooded Chianinas, such crosses are competitive in pulling contests, with a calmer temperament.

Origin |

England; United States |

|

Color |

red |

|

Mature Weight |

1,700 lbs. (770 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

quick and alert |

|

Tractability |

10 |

|

Other |

easy to color match |

The Devon is a fast-moving breed, with a long history as a superior draft animal.

Beef Devons and a small population of Milking Devons both exist in the United States. According to New England ox teamsters, “The breeders of Beef Devon have bred the brains and brawn right out of their animals.” Most Americans who seek Devons for work will not consider the Beef Devon.

The Milking Devon is a rare breed. Only about 500 cows survive in the United States. Supposedly descendants of the original cattle used by early pioneers, they seem to have retained most of their original characteristics. The Milking Devon closely resembles early cattle from North Devonshire in England, where it was one of the fastest, most agile, and adaptable of all the English breeds in the yoke. The Devon is small in size, but what it lacks in size, it makes up in character.

The Devon is all red, varying in shade from a deep rich red to light red. Devons have yellow skin and creamy white horns with black tips, and usually a whitish gray tail switch.

Origin |

Ireland |

|

Color |

black, dark red, dun |

|

Mature Weight |

1,000 lbs. (455 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

small |

|

Temperament |

quick and alert, at times to a fault |

|

Tractability |

9 |

|

Other |

long horns, heavy muscling |

Dexter cattle are one of the smallest breeds of cattle in the United States. They are quite lively.

This small all-black or dun breed, developed in Ireland, has gained popularity in the United States among small-scale farmers. Dexter working steers or oxen can be found at many ox competitions. They are a nice size for people concerned that cattle may get too large for their facilities, transportation options, or children.

Dexters tend to be high-strung, however, often a function of being allowed to nurse instead of being bottle-fed. They are heavily muscled for their size and grow long horns. They are great for teamsters interested in keeping the animals for fun and to do some light work around the farm or woodlot. This is a good breed for experienced younger teamsters interested in a team that won’t outgrow them.

Origin |

Holland |

|

Color |

white belt around black body |

|

Mature Weight |

1,700 lbs. (900 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

moderately docile |

|

Tractability |

3 |

|

Other |

rare breed |

The Dutch Belted is a striking breed, medium size and easy to match together.

Called Lakenvelders or Lakenfeld Cattle in their native Netherlands, this breed was developed as a dairy animal and should not be confused with the polled Belted Galloway.

Although considered rare, Dutch Belted are popular as oxen. They are easily distinguished by their color, which is all black except for a continuous white belt around the barrel that begins at the shoulders and extends almost to the hips.

A dairy breed that is lean and angular like a Holstein, it is of medium size and grows in pace and size similar to the Ayrshire. Mature steers in working condition weigh about 1,600 to 1,800 pounds. In temperament they are similar to the Holstein — generally easy going and calm, but not as docile and poky as the Brown Swiss or Hereford.

Origin |

England |

|

Color |

dark red with white face |

|

Mature Weight |

2,200 lbs. (1,000 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

moderately docile |

|

Tractability |

3 |

|

Other |

rare breed |

The Horned Hereford is not as common a beef animal as it once was, but its calm nature is a trait the breed is known for.

Originally developed as a draft animal in England, the Hereford is reddish brown with a white face and belly, often with a narrow white stripe along the top line. The breed is medium to large, fattens easily, and tends to carry more flesh than it did in the old days. Individuals are easy to match in color, but can vary greatly in size. They are easygoing and calm.

In the United States, Herefords have changed considerably over the past 150 years. Originally used in the eastern United States as multipurpose animals that met all the needs of the small farmer, they were later selected only for beef. Their value as draft animals dropped tremendously when they were bred to be short and fat at the turn of the last century. Modern animals are large, heavily muscled, fast-growing, and efficient beef animals.

The most popular type today is the Polled Hereford, meaning it has no horns. Horned Herefords are still around and occasionally seen in a yoke. In Nova Scotia, the Horned Hereford is a preferred breed to cross with Shorthorns or Ayrshires to produce attractive, heavily muscled animals to use in the head yoke. Hereford-Holstein crosses are also popular among today’s New England ox teamsters.

Origin |

Netherlands |

|

Color |

black and white or red and white |

|

Mature Weight |

2,500 lbs. (1,135 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

large |

|

Temperament |

docile |

|

Tractability |

3 |

|

Other |

grows rapidly |

Easy to find, the Holstein is a popular breed of dairy cattle that make fine work animals.

Dutch settlers first brought the Holstein to North America from the Netherlands in 1621, but the breed was not kept pure. Later importations during the 1850s and 1860s were more successful. These cattle are often referred to as Friesians in other countries, and the Beef Friesian is found as a breed in the United States.

A large breed, the Holstein is noted for its rapid growth with little fat accumulation until maturity. A two-year-old animal may weigh more than 1,400 pounds. Mature animals often weigh well over a ton, with some reaching 3,000 pounds. This breed is not as tall as the Chianina, but some animals reach almost 6 feet at the withers.

The Holstein is one of the more commonly used breeds for oxen in New England. It is popular for beginning teamsters because the calves are easy to find and relatively inexpensive to purchase. While Holsteins are readily trained, however, they often grow too quickly for a small teamster.

Matching a team is challenging because of the great variation in color patterns. Holsteins are normally black and white, but occasionally red and white animals can be found.

Origin |

England |

|

Color |

any shade of brown |

|

Mature Weight |

1,600 lbs. (725 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

moderately active and excitable |

|

Tractability |

7 |

|

Other |

easy to color-match |

The Jersey is a smart and active breed that can make fine work animals for the farm or show ring.

This small breed of dairy cattle was developed on the island of the same name in the English Channel and was first brought to the United States in the early 1800s. Jerseys are fine boned and lack the ruggedness of the heavier breeds. They tend to mature early, which can be an advantage in pulling competitions among lightweight animals. Well-fed mature steers weigh about 1,600 pounds. Jerseys vary from light brown to almost black, with or without white patches.

This active, alert animal tolerates warm climates better than other dairy breeds found in the United States, but its small size and light muscling can be a disadvantage for heavy work. Jerseys are commonly trained by young teamsters and make adequate work animals for the farm.

Origin |

England |

|

Color |

black with white stripe down back and belly |

|

Mature Weight |

2,000 lbs. (900 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

moderately active and alert |

|

Tractability |

6 |

|

Other |

rare breed |

These oxen are Randall-type Linebacks, a medium-sized breed with a striking pattern.

In the United States Linebacks are varied in genetic background, yet black and white animals similar to the Gloucester cattle of England can still be found as oxen. The Randall Lineback, white with blue roan coloring, is also found in the United States.

The Lineback cattle are popular among people who show oxen because of their striking appearance — black or blue roan with a white stripe along the back and belly — and because they are active but agreeable in the yoke. Linebacks are of medium size, with mature steers weighing from 1,600 to 1,800 pounds.

Origin |

England |

|

Color |

red, red and white, roan |

|

Mature Weight |

2,300 lbs. (1,045 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

large |

|

Temperament |

moderately docile |

|

Tractability |

4 |

|

Other |

matures slowly |

One hundred years ago the Milking Shorthorn was the most sought-after breed, due to its versatility, and it has long been the most popular breed of cattle used for work in New England. The cows produced ample amounts of milk for the farm and the steers were trained as oxen and later used for beef.

The breed is hard to beat for its disposition and willingness to work. It is preferred over the Beef Shorthorn because it is more angular and athletic and does not put on excess weight as easily, especially when young.

Milking Shorthorns are medium in size and do not grow as large as Holsteins, but generally carry more flesh and are easier to match in color. Individuals may be red, red and white, all white, or roan (alternating red and white hairs). It should be noted, however, that many breeders of Milking Shorthorns in the United States have been crossbreeding with Red Holsteins to improve milk production in the breed. This has resulted in animals that are larger, as well as being less heavily muscled with finer bones, particularly in the legs.

Milking Shorthorns have historically been called Durham cattle, and many ox teamsters in New England still refer to them by this name. They are popular among young teamsters, as they can still be purchased as calves from dairy farms. In other regions Milking Shorthorns are nearly impossible to find.

Origin |

United States |

|

Color |

any color or combination |

|

Mature Weight |

1,800-2,000 lbs. (815–900 kg.) (average) |

|

Height |

medium |

|

Temperament |

active and alert |

|

Tractability |

10 |

|

Other |

impressive horns |

Texas Longhorns come in a variety of colors and patterns, but their lean bodies and long horns make them easy to recognize.

The Texas Longhorn originated from Criollo cattle brought as early as 1609 by the Spanish, via Mexico, into the territory that is now Texas. Criollo cattle are the same as the Corriente breed used today primarily for roping and steer wrestling in rodeos. Small and nondescript, they were some of the first cattle brought to this continent by the Spanish. The Criollo evolved through decades of natural selection in the harsh environment of the wide-open and arid range.

While early examples of the breed were rangy and varied greatly in size and quality, modern Texas Longhorns have become a true beef breed. They differ from other modern beef cattle in being leaner and having no color standard. Of course, they also grow a tremendous set of horns.

The Texas Longhorn is one of the more common breeds used for oxen outside New England. It is popular for parades, historic reenactments, and movies, especially in the western United States. In New England, Longhorns are seen primarily in pulling competitions. They are medium sized and easy keepers. Their temperament is sometimes considered challenging, probably the result of running free with their dams or of training that would be considered inadequate by New England standards. It should be noted that their large horns can be difficult to manage in the traditionally sized neck yoke or the head yoke.

Many other purebred cattle are used as oxen in New England, including the Simmental, Gelbvieh, Salers, Scotch Highland, Piedmontese, Pinzgauer, and Guernsey. Any one of these breeds can make fine oxen. Some breeds may be hard to find in the northeastern United States, a predominantly dairy area. Others, like the Guernsey, are sometimes considered too lightly muscled, lack the ruggedness desired in a draft animal. The Scotch Highland, with its long hair, cannot tolerate working in warmer weather.

A few breeds are worth noting because of their popularity in nations around the world. Globally the most popular cattle used for draft purposes are probably the Zebu, known in the United States as the Brahma type.

The word Zebu refers to a species of cattle, rather than a breed. Just as hundreds of European breeds belong to the Bos taurus species, hundreds of breeds belong to the Zebu or Bos indicus species. The characteristics of the Zebu include a large hump (composed of fatty tissue that becomes larger when the animal is well fed), greater tolerance to heat and humidity, and the ability to sweat more efficiently than Bos taurus. Finally, the Zebu cattle also have the ability to develop some resistance to internal and external parasites.

In Asian countries, Zebu breeds are numerous, with many draft characteristics that have been maintained for centuries. In India, for example, breeds like the Mewati are known for their powerful frame and their docility as workers. The Nagori is a famous trotting breed, prized for road work. The Bargur is a fiery, restless, and difficult-to-train draft breed. The Sahiwal, common in Asia, Africa, and Australia, is noted for its milk production and fine beef qualities, making it popular to cross with local breeds.

In Africa, many breeds are generally referred to as Zebu animals. Imported breeds influenced the Madagascar Zebu, a good-sized triple-purpose breed. The preferred breed for use on the farm is the small East African Short Horned Zebu, with its small and compact but rugged body.

Other breeds worth noting are the Ankole and Watusi from East Africa, with their giant horns. They are worked by some farmers, but are considered inferior by others because they have no humps, an opinion resulting more from yoking technique than working ability. However, the Ankole and Watusi are smaller-boned than the Zebu and have less muscling in their rump and legs than Zebu of similar size.

West Africa has the N’Dama, one of the humpless Longhorns. It has a great tolerance to trypanomiasis, an important attribute in areas that are infested with the disease spread by the tsetse fly (and therefore not a problem — or advantage — in North America). The N’Dama is a solid yellow, fawn, dun, or khaki color with long horns that turn upward. It is a tiny animal: adults may weigh only 400 to 600 pounds. Yet this animal is rugged, active, and agile, and anything but docile when range-reared. N’Dama are usually worked in teams as bulls with simple head yokes.

From western to central Africa another common breed is the Fulani. Noted as a triple-purpose breed, it grows larger than the N’Dama and has better milk production. The Fulani weighs up to 1,000 pounds and is often used for crossbreeding. It is a large breed by African standards, and has the additional benefit of being more trypano-tolerant than other Zebu-type cattle.

Many teams are not made up of purebred animals. Some teamsters who are eager to combine the qualities of two or more breeds seek crossbred animals. Crossbreeds have an advantage for the teamster who desires characteristics of animals not found in the local region.

One typical characteristic is the ability to meet certain weight requirements of pulling classes. Many crossbreds used for oxen in New England are Holstein crosses, because Holsteins are the most common cows in the area. With the prevalence of artificial breeding, some dairy farmers are persuaded to breed their cows to non-Holstein bulls.

Shorthorns are commonly crossed with Holsteins in New England, where Milking Shorthorns are becoming hard to find. Teamsters persuade local dairy farmers to breed their Holstein heifers to a Milking Shorthorn bull. The teamsters purchase the resulting calves at birth and bottle-feed them. The cross combines the faster-growing characteristics of the Holstein with the more flashy and athletic appearance and heavier muscling of the Milking Shorthorn. The resulting animals are often easier to color-match than pure Holsteins and may be all black, black and white, or blue roan. The crossbreeds are usually more active than pure Holsteins.

Crossing the Holstein with the American Milking Devon combines the larger size and more docile temperament of the Holstein with the more active nature and aggressiveness of the Devon. The result is a black animal that is slower growing than the Holstein with the more athletic and muscular appearance of the Devon. Compared to Holsteins, this crossbreed develops more muscling on the same amount of feed. They are often used successfully in lightweight pulling classes, and are popular among young teamsters not yet ready to train the more challenging purebred Milking Devon.

The Chianina-Holstein cross is popular in New England. It is usually dark brown to almost black and combines the height, growth, and activity of the Chianina with the deeper body, more solid appearance, and more docile temperament of the Holstein. It is a desirable cross among ox teamsters striving for really large but more easily controlled oxen to be used in pulling competitions.

Dairy farmers frequently cross Jersey bulls on Holstein cows to create a cow that makes more milk than a Jersey, with higher components of butterfat and protein than the Holstein. The cross reduces calving difficulties for Holstein heifers yet, with more muscling and frame, the calves are faster-growing and larger than a pure Jersey. Their temperament falls between the high-strung and head-strong Jersey and the moderate Holstein. The solid black or blackish brown offspring are easy to match in color. The breed grows to be about 1,600–2,000 pounds (larger than the Jersey) and makes fine medium-sized oxen for show or farm work.

Ayrshire. Known for being more high-strung than other dairy breeds, Ayrshires tend to carry more flesh than Jerseys or Guernseys do. They have large sweeping horns and are medium in size.

Brown Swiss. The most rugged of the dairy breeds, with exceptionally strong feet and legs, Brown Swiss can be quite large, calm, and often slow to a fault as they get older. Although a good choice for a beginner, they often outgrow young teamsters.

Charolais. This all-white breed was originally bred and used as a draft animal in its native France, where it was worked in a head yoke. Oxen of this breed are less often seen in the United States, but with good training their rugged frame and heavy muscling are desirable characteristics.

Chianina. This is said to be the largest breed of cattle in the world. It is not by coincidence that the all-white Italian variety has gained popularity in the northeastern United States, where this breed usually dominates ox competitions. These are big-boned, tall, and heavily muscled cattle that were bred to work.

Chianina-Holstein. As the huge Chianina has come to dominate many of the pulling classes in the northeastern United States, some teamsters seek a cross between it and the Holstein to create an ox with a more moderate temperament. The Chianina bull is often bred artificially to Holstein cows to create an animal for the “Free for All” or unlimited weight class in ox pulling competitions.

American Milking Devon. The triple-purpose “old style” Devon is the most popular Devon breed for use as oxen. Lively, small to medium in size, they are most like the cattle originally bred for draft purposes.

Devon-Holstein. Most often a cross between the Holstein cow and an American Milking Devon bull, this all-black or mostly black animal is larger than the Devon and more moderate in temperament.

Dexter. One of the smallest breeds of cattle in the United States, the Dexter was a small farm cow, developed in Ireland. The breed carries more flesh than more modern dairy breeds, and can make a fine team of oxen. They do require a little more experience in training and handling as oxen, as they are more independent and more willing to test you than common dairy breeds.

Dutch Belt. More refined than the Holstein, this medium-sized breed is easy to match and frequently sought out by ox teamsters who want striking show cattle.

Holstein. The most common dairy breed in the United States and Western Europe, Holsteins grow to be large oxen but may not fill out their frames until they get some age on them. As the most productive dairy breed, the cows have been bred exclusively for milk production, and many of the traits that are desired in oxen, such as muscling and rugged feet and legs, have been lost. However, their temperament is usually easy to get along with, and they make fine oxen for general work and showing.

Horned Hereford. Common historically as a draft animal, the Horned Hereford has remained a breed of choice for many ox teamsters using a head yoke, especially those in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Hereford-Holstein. This breed is easy to match in color, as all of the animals are black with a white head. Most often the offspring of Holstein cows and Hereford bulls, the breed is known for its calm disposition and medium size.

Holstein-Shorthorn. Often all black or blue roan, this breed combines the fleshy appearance of the Milking Shorthorn with the dark color of the Holstein.

Highland. A long-haired, striking breed with long sweeping horns, Highland oxen are most often used for showing, as they are less tolerant of heat when worked hard. The team pictured here was trained to be driven with bridles and bits, which, it should be noted, is more of a novelty than common practice.

Jersey. This small dairy breed can be easy to find and cheap to acquire in dairy areas, because the bull calves have little value. Jerseys can be high-strung, but with good training they can make fine oxen for a farm or show.

.jpg)

Jersey-Holstein. Breeding a Jersey bull to a Holstein cow can minimize calving difficulties, especially with heifers. The resulting crossbred cow’s milk has more protein and butterfat, and the bull calves (often cheaper than Holstein calves) make fine oxen. The Holstein genetics moderate the Jersey’s temperament and add frame and size. The all-black or blackish brown animals are easy to match, often seen as both show and farm teams.

.jpg)

Milking Shorthorn. For nearly a century the breed of choice for teamsters in the Northeast, these are medium-sized, carry more flesh than other dairy breeds, and have a desirable temperament as work animals.

.jpg)

Randall Lineback. This is a rare breed of cattle in the United States. Small in size, it is known for its unique color markings: a blue roan color, a distinct white line on the back, and a brockle face. They are most often sought for use in show, and their temperament is usually easy to work with.

Texas Longhorn. Developed in the United States from Spanish cattle, this beef breed comes in many colors and has the longest horns of any cattle bred here. The animals tend to be harder to manage than other breeds, but they are long-lived and have made their way into the smaller weight classes in pulling contests in the northeastern United States.

Zebu. This is a common name for Bos indicus cattle, largely originating in Asia and particularly common in India. In North America, the Brahma was a Bos indicus breed developed for beef production. The Zebu are actually a different species than the European breeds, which are Bos taurus cattle. Zebu cattle come in hundreds of different breeds and are more commonly used as oxen around the world than are Bos taurus cattle.

My sons Luke (age six) and Ross (age twelve) have always been interested in our farm and its animals. For as long as Luke can remember, I have had only American Milking Devon working steers or oxen. The Devons we have kept, however, were not animals they were allowed to play with; my sons could not even enter their pasture without an adult. The cows were very protective of their calves, and the animals would have taken advantage of the boys if they had a chance.

When the Devon steers were yoked up, both boys learned how to drive them under my supervision. They often went for cart or sled rides, and they helped me haul our firewood out of the forest. In the yoke, even the best-trained Devons were quick to take advantage of the boys and just walk or run off, as they would with any teamster who did not know what he was doing.

Ross remembers a pair of Dutch Belted steers we had raised on a bottle from babies, and he says he enjoyed that team more than any of the Devon steers. He showed this team at a fair. I was quietly hoping he might take to training and driving his own team. However, when the opportunity arose, I purchased more Devon steers, and over the next four to five years the interest he had in steers seemed to disappear with the sale of the Dutch Belted team.

The Devons are fast-moving cattle, and some teamsters have told me that they are not an old man’s team of choice for this reason. They are also not the likely choice for a budding young teamster, for all of the reasons above.

I decided that the breed I began with, 30 years ago, might be the best way to interest Luke in training oxen, since I did not believe Ross had any interest. I purchased three Brown Swiss calves, and both boys quickly fell in love with them. The boys enjoyed bottle-feeding the calves, and they halter-trained all three calves while they were still on the bottle. Every time I said we ought to work with the calves, the boys jumped at the opportunity. With the boys always interacting with them, the calves almost seemed to train themselves. They were calm, slow moving, and fun for the boys to work with. I never had to worry about them running off or taking advantage of the kids.

According to Ross, “The Brown Swiss are easier to work with, as they are not as jumpy, and just more friendly than the Devon calves.” He went on to say, “It seems like the Brown Swiss understand you more than the Devons.”

I have to admit the Devon calves we’ve had have always run with their mothers on pasture until they were weaned. This always makes for more challenging training, no matter what breed is chosen. Even with the same training, however, Ross summed it up well when he said, “The Devons are more likely to want to do their own thing.”

According to Luke, who wrote his first story in kindergarten about Bill, his favorite of our three calves, “Brown Swiss are a lot easier to train, and that is basically it.”

In selecting a team of oxen, consider how the animals will be used and the environment in which they will live. Then find a breed that best suits your needs. When evaluating animals for purchase, keep in mind the characteristics of an ideal ox. Your team will be more valuable and trouble-free if both individuals have a desirable conformation and a similar disposition.

Training older animals is more difficult than training calves, but buying older calves or yearlings eliminates some of the guesswork in trying to match two animals as a team. While no team is perfect, if you follow the guidelines outlined in this chapter, chances are you will end up with two well-matched animals that work well as a team.