Housing for working cattle varies as much as the cattle do themselves. Oxen do not require elaborate housing. Cattle in a variety of climates are kept outdoors most of the year. Pastures may provide both an excellent environment and a readily available feed source. Keeping a team on pasture also minimizes the need for providing bedding, handling manure, and hauling feed. On the other hand, this method does have its drawbacks.

While pastured oxen are easy to care for, they may not get the regular handling essential to maintaining a well-trained team without some effort. Good pasture may provide too much feed for mature oxen that are allowed to graze all the time. Cattle that spend four to six hours working each day may not have this problem, but mature oxen that work less often will soon become obese. Regularly moving them to a corral or barn may be necessary to prevent overfeeding.

Finally, housing for cattle should have some flexibility, especially if you purchase your animals as calves and grow them to maturity, or if you keep different breeds or species in the same facility.

An ox team in New England was traditionally housed in a barn during the winter. The cattle were worked on most days and spent nights in the barn, near other cattle for ease of feeding and cleaning. During bad weather many teams may have stood idle for days or even weeks.

Neck chains, with the cattle tied to wooden upright poles, were typical in the late nineteenth century. In earlier periods crude stanchions or wooden collars were used to hold the animals in the barn. Few barns had loose housing.

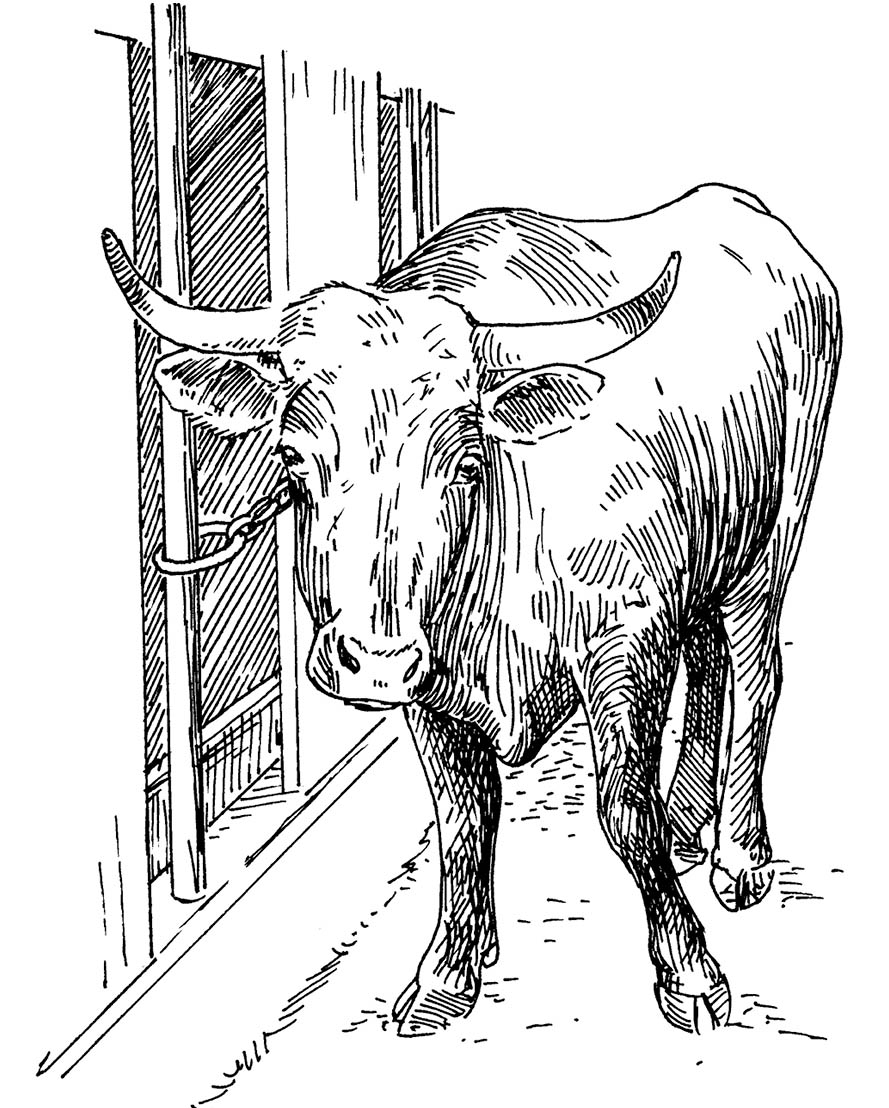

Oxen in New England are housed in much the same way today. They are often kept in barns where they are tied individually. Neck chains or leather collars with short chains and swivels are preferred because they are flexible and comfortable. Stanchions work, but they restrain an animal’s movement, especially when lying down. A young team of oxen quickly outgrows stanchions designed for cows.

An ox is usually tied near his teammate in the same position as he works in the yoke. This practice helps familiarize the animals with each other. Tying also aids in teaching the animals how to step in and step out during grooming and barn cleaning.

Cattle are tied in the barn as they would stand in the yoke.

Listing rigid dimensions or recommending specific housing designs would be futile, since the sizes of oxen and the budgets of teamsters vary widely. If your cattle will be housed indoors, make your barn or shed large enough for your animals. Many beginning teamsters starting with young animals do not realize how big the animals will get.

An old converted dairy barn may work fine for young steers, but the animals will soon be standing in the gutter and be too tall for the stanchions. An ox grows to almost twice the size of a cow of the same breed and therefore requires more space. Design doors, stall dimensions, and wood floors with the largest oxen you might keep in mind.

Since most oxen have horns, animals housed in cramped quarters should be tied. If you do use loose housing, be sure to provide ample space for all animals. Minimize corners and tight quarters to allow the less dominant animals to escape if chased by larger ones.

Tie stalls come in many possible designs. Simple stalls or tie-ups that are similar to but larger than those used in dairy barns work best. Dairy stalls are about 4 feet wide and 6 feet long, not including the 2 feet of manger space, called “lunge space,” which allows cattle to lie down in a normal position, and to throw their heads forward as they get up. Stall space for medium-sized oxen should be about 4 feet by 8 feet. Stalls may be smaller for calves and the smaller breeds like the Dexter, and must be a lot larger for the huge breeds, such as the Chianina.

An ox is considerably larger than a cow of the same breed, and therefore housing designed for cows is often too small.

Modern dairy farmers have moved away from the stanchion barns with a few small windows far above the animals’ heads. Dairy cows produce more milk in an environment that is comfortable and cool. Oxen benefit from the same treatment. The animals get the greatest benefit from air movement when windows are arranged on the wall they face while tied or in their stalls, allowing air to flow past the animals in hot weather.

Cold weather and snow do not affect cattle as much as wind and cold rain, which causes them to run for shelter. Even when cattle are tied in a barn or stall, a dry environment and excellent ventilation are critically important for good health. Cattle are more comfortable in an open shed that is draft-free and dry than in a stuffy, hot, and humid barn where the animals are crowded and damp. Leaving barn doors and windows open during winter is healthier than shutting the barn up tight.

Keeping oxen indoors entails frequent cleaning of stalls. Cattle prefer to sleep on dry bedding. They do not like to lie on wet, frozen, or muddy ground.

Steers, oxen, and bulls “piddle in the middle,” or urinate beneath themselves. Gravel, dirt, or sand floors offer the best drainage and animal comfort, but they are hard to clean. Wood floors are more comfortable than concrete but require lots of bedding, and when the wood rots the floor must be replaced.

Concrete is easy to clean but offers no drainage and little animal comfort. One way to overcome this problem is to put rubber mats over the concrete and put a small drain, or drill holes in the concrete, to drain away urine.

Concrete and other hard surfaces are detrimental and can result in lameness in animals that are prone to swollen hocks and diseases of the hoof. Concrete floors require more bedding than other systems. Extra bedding helps prevent injury to the hocks and legs and prevents urine from making direct contact with the skin.

A barn with gravel under the oxen and concrete or wood in other areas offers the best combination of surfaces. The concrete alleys and floors are easy to clean, but the steers are standing on a natural surface, which is best for their comfort and well-being. Heavy older oxen benefit the most from a floor that offers a more natural surface.

Neck chains or leather collars, attached by means of a short chain to a steel ring around a rugged vertical steel pipe or hardwood pole, offer maximum comfort to a restrained animal. I do not recommend steel pipes or bars that run horizontally in front of the animals’ necks. While a horizontal pipe a few feet off the ground may offer good restraint and keep the animals from stepping on their feed, it creates calluses and sores on the animals’ necks, which will interfere with or be irritated by the yoke.

Make sure the neck chain, collar, and pipe are strong enough to hold an animal that fights it.

Small calves in big stalls or tie-ups will turn around to see what is going on, often resulting in manure and urine in the feeding area. Calf hutches work well for bottle-fed calves in all seasons of the year. If the animals are kept in the barn, calves must be separated to minimize the transmission of disease.

Individual feeding is important, especially with calves.

If larger animals try to turn in their stalls, temporary dividers may be necessary to restrict movement. Dividers suspended from the ceiling are more comfortable for large animals and are less likely to be destroyed than temporary dividers on the ground.

Older oxen often need to be limit-fed, so a comfortable tie-up can be part of their routine.

To keep feed clean and dry, design the stall with a slightly raised feeding area. Although high feeders will keep the feed clean, the feeding area should not be similar to that in a horse stall. This is because cattle do not like to reach up or hold their heads high in order to eat. Cattle prefer to feed with their heads down. The feeding area should be about 6 inches higher than the surrounding floor.

These tie stalls have gravel or a platform that raises steers 2" to 4" above floor level, with a manger 3" to 4" above the platform. Steel pipes slide into holes drilled into two horizontal wooden beams and can easily be pulled out for replacement if bent by a strong ox. At feeding time each animal’s collar is snapped to a short chain attached to a steel ring around one of the poles.

No single ox-housing design works best for all teamsters. Keeping animals tied in a barn requires daily handling of the animals, giving them little freedom but critical and frequent human contact. However, regular handling may also be incorporated into outdoor systems of management. A corral may be used to keep animals in close contact with humans. Capturing and tying the animals at feeding time is another way to incorporate regular handling into your management program.

Some of the healthiest and cleanest oxen spend most of their time outdoors. Animals with freedom to move around in fresh air and sunshine are less likely to have ringworm, respiratory problems, and external parasites such as lice and mites. These health problems occur more frequently in barns where cattle are kept in tight quarters.

Is a barn or a shed a better housing solution for oxen? Many teamsters, especially in New England, believe in tying up oxen in a barn with their teammate daily. While regularly tying animals together in a barn is good for training and makes individual feeding easy, in some ways it is tougher on the animals and people who care for them.

With this in mind, I decided to get my wife Janet’s perspective on housing oxen. She has been a partner in most of my endeavors with oxen, if (she would admit) not always by choice. When we bought our little farm in Berwick, Maine, we started with a shed for our pair of Dutch Belted steers because that was all we could afford. We had our hay under plastic and hauled water from the house all winter. It was less than ideal for feeding and watering. However, the animals stayed cleaner, we used less bedding, and we did not constantly have to shovel their manure and wet bedding.

The next year we designed a barn for a pair or two of oxen, as well as some pens for future animals. Janet said I could plan the inside, but she wanted a say on the outside. She wanted the barn to match our house in trim color, siding, and roofing. She also wanted to minimize the number of trees I cut down, so the barn would fit nicely into our wooded, riverside farm.

Our final barn was 24' by 24' with a “salt-box” roof and a hayloft that might hold 300 to 400 bales of hay. I knew the barn size and hayloft would limit the number of steers I could keep.

We kept the sheds we had originally built for the Dutch Belted steers; in fact, 17 years later they are still there, having been used every winter to house oxen. When I travel, often for days, weeks, or even months, Janet has found a number of advantages in the sheds.

“If you [Drew] are gone, I have to clean out the shed only once every few days. The steers stay cleaner, as they are not lying in their own urine-soaked bedding. We use less bedding, which can be expensive, and they have fresh air, especially in winter. I think they prefer to be out, rather than tied up all the time. The easiest time is when they are on pasture in the summer, because then there is no shoveling of manure.”

Janet also notes some disadvantages: “We have to haul water and hay to the paddock and sheds from the barn. I hate doing that, especially in winter. An automatic waterer would help, and a small hayloft in the sheds. Finally, the hitching rail near the sheds where you individually feed them is not something I like either. It’s not fun trying to feed grain and tie the Devon steers up with those horns.”

We have always had tie-ups in the barn for at least two teams. Janet’s comment: “There is more cleaning out, and we use more bedding. The way it is set up you have to get up near their heads to feed them in a crowded space. The advantages are that the water is nearby and the hay is overhead. Even so, I would like warm water in the barn, more lights from the house to the barn (it is a few hundred feet from our house), and a staircase rather than a ladder to the loft.”

Janet knows the barn is more accessible for taming calves, especially for our boys. As with any housing system, however, there are advantages and disadvantages. I learned a few things asking my wife after 20 years what she thought of our ox housing.

Whether oxen are kept outdoors or only occasionally let out, they are usually fenced in. The fence should be of a type suitable for beef or dairy heifers and steers. Heed the old adage that the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence: No matter what type of fence you put up, your animals are more likely to remain in their pasture if it offers adequate feed, compared to a pasture with better grazing on the other side of the fence.

Solid wood or woven wire makes the most rugged and trouble-free fence, provided it is tall enough that the animals cannot graze over it, and strong enough that the animals cannot push it over. A single electric wire inside the fence will keep the animals from leaning on or over it. The combination of the physical barrier provided by the wooden fence and the psychological barrier provided by the electric wire is probably the most foolproof system, but it requires a substantial investment in time and materials.

Barbed wire works too, with a lower investment, but I have seen many cattle walk through even the most tightly stretched 4- or 5-strand barbed-wire fence. Cattle are much tougher than horses and more careful and deliberate in pushing through a barbed-wire fence. I once had a pair of Brown Swiss that would push against barbed wire until a couple of strands broke, then amble out of the pasture. The act was intentional and they never received more than a few small cuts. Apparently the greener grass on the other side was worth it. I have chased more animals that escaped from barbed wire than from any other fencing system.

On my farm I use electric fence almost exclusively. My cattle remain outdoors for most of the year. A high-tensile multistrand fence, with a powerful charger and good grounding, is hard to beat for animals that have been trained to respect it. I have never had animals get out, unless the fence charger was struck by lightning or I turned it off and forgot to turn it back on. In both cases it was days before the animals learned that the fence was off. Even then only one animal out of the herd got out. The bawling of the remaining animals informed me of the escape. A high-tensile fence is more expensive than other fences, as the wire is heavier gauge than standard 18- to 20-gauge electric fence wire, but it also provides a stronger barrier if an animal bumps into or is chased into it.

Common one- or two-strand electric fences can be used successfully with animals that were trained to respect a high-tensile fence charged with a high-voltage, low-impedance system. In this case, one or two strands, on wooden or fiberglass posts, usually works. Sometimes, however, the animals push each other through the fence, chase a calf through, or knock over posts by rubbing on them with their horns.

Any electric fence has a number of disadvantages. When it fails, cattle are much quicker than other farm animals, such as horses, to figure out that it is off. Oxen with horns tend to touch the wire with their horns, and on dry or frozen ground they do not get a good shock through the horns. If the weed load on a long stretch of fence becomes heavy and wet, even the best fence charger fails to deliver a strong shock, resulting in animals escaping. On the other hand, a 5-foot-tall high-tensile fence with strong and long-lasting posts makes a permanent, attractive, and low-maintenance barrier fence.

Dry is good and wet is bad when it comes to cattle housing and ventilation. Remember this simple rule to minimize the possibility of disease and maximize your animals’ comfort.

Whatever kind of housing you choose, make sure it provides a dry, bedded, and well-ventilated place where your animals can get out of wind and rain in winter and enjoy shade during summer. Equally important, the design should be one that encourages you to handle your animals regularly.