![]()

NEARER, MY HOUSE, TO THEE

Retrospectively, it seems as though fate was on my father’s side. At the time, however, he was disagreeably conscious of having come up against a character as forceful as his own. Rosemary could be managed; her mother was another matter.

Margot had been frank with him at their first interview. She did not regard a junior bank clerk, however glorious his family connections, as a suitable consort for her daughter. Rosemary’s heart was set on farming; it followed that George, too, must look in that direction.

Margot spoke with her husband; the result was the offer of a shared tenancy of one of his finest Welsh properties, Croes Newydd. Rosemary had already been encouraging George to think of himself as a man of the land (‘my great big, strong, tough farmer to be’). Now, she urged him to consider the charms of Croes Newydd and the pleasure they would have in running a farm together. Her mother, meanwhile, made it clear that if he did not apply himself to farming, their consent to the engagement might be withdrawn. (She had already insisted that it should remain secret for three months.)

On 13 February 1946, five days after his twenty-third birthday, my father took the plunge. Resigning from his job at the Fakenham branch of Barclays, he ended, for good, his days as a paid employee. With no future prospects, he was terrified.

‘Promise you will never leave me,’ he wrote anxiously that night to Rosemary.

‘Woman is said to be fickle, but I am not!’ she reassured him. This was comforting, but he was disturbed to note, a little further on in her letter, that ‘darling Mummy’ had been demanding an answer about the offer of a Welsh farming partnership. Rosemary was unsure about spending her first married years in a house which was not her own. ‘I don’t fancy the idea of sharing,’ she admitted. Neither did George, but he was in no position to turn down the offer of a free home and a source of income. At that precise moment, he had neither.

This was the week in which a promising letter arrived from Thrumpton: his uncle had formed a new plan that might, conceivably, be of interest to his nephew. If George could spare the time from gadding around nightclubs and meeting members of Rosemary’s illustrious family – Charlie’s Byron’s notes were always spiked with malice – perhaps he would care to pay a visit.

He went at once, and was received with warmth. ‘We had a most excellent dinner,’ he noted (my father loved his food), ‘bonne femme soup, roast pheasant, vanilla ice bombe with hot chocolate sauce, and cherries in brandy!’ Champagne was produced, and toasts drunk to the happy couple, before the new offer was made. Smiling benignly, Charlie Byron announced that he had thought things through. While conscious of the claims of his own distant relations on the House, he felt that it was only right that George, with his great love of the place, should enjoy it, in due course, as a life tenant. Later, George must understand, the House would have to revert to the Byrons. For the present, since George was unemployed, perhaps he and Rosemary would consider running the Home Farm at Thrumpton – and acting as companions to a fond old couple. He wanted, did he not, to be a farmer? He wanted to live at Thrumpton?

Charlie, in other words, had finally recognised the convenience of having a dependable, affectionate nephew around to work for the estate and act, if necessary, as general supervisor. No Byron cousin was likely to show him the same devoted care. My father accepted the proposal at once. Nothing, he told his uncle, would please him more.

Breakfast the following morning was taken after prayers. Charlie Byron, encased in what had once been a dashingly fashionable teddy-bear coat, retired to meditate on the Sunday sermon in the lavatory. Anna clasped her nephew’s hand and led him down the drive. Her pride was evident and glowing; halfway to the village, she stopped to boast that she had been the mastermind behind the scheme for George’s happiness. Proudly, she pointed between the trees to the home she had singled out for him.

Her satisfaction was well-founded. I, like my parents, have only happy memories of the house where, a few years later, I was born. A friendly, unpretentious building with ample gables, an eighteenth-century barn and a spacious garden, Thrumpton Lodge was where I would have liked to grow up, had I been given the chance. For my father, it was ideal; only a low brick wall separated him from the House he now looked forward to inhabiting, when the time came; in the meantime, he could enjoy all the beauty of Thrumpton’s benevolent atmosphere, introduce Rosemary to his favourite walks through familiar scenery, and have the added pleasure of feeling that he was doing the old couple a favour in lifting some of the burdens of ownership from their shoulders.

There was only one problem, and Anna was confident that he would solve it. The present tenants of Thrumpton Lodge were family friends who had no plans to leave; Charlie had already made it clear that he was not prepared to serve notice on them. What, then, was to be done? Aunt Anna tapped George’s arm with a gloved finger. He could be such a persuasive boy when he set his mind to it, she said archly; this was the time to show off his negotiating skills.

I have no records to show what form of emotional blackmail was deployed on the tenants whom my father visited at the London flat before the day was out; I do know how impossible it was to resist his will, when he set his mind on an objective. Perhaps he simply wore them down; perhaps they were charmed at the prospect of helping a young and homeless couple. All I can discover is that his ends were obtained. They ended by agreeing to cut their tenancy short; their house would be his by late autumn.

‘A triumph!’ he wrote to Rosemary from London late that night. ‘A complete triumph!’

It’s hard to disagree. Nevertheless, the shock to my mother when she paid her first visit to Thrumpton two weeks later was considerable. Nothing in George’s lyrical descriptions had led her to expect the House’s air of wan neglect (she still shudders at the memory of pea-green painted walls, dusty piles of prayerbooks, moss-grown drives, broken windowpanes, and rats). This was not what she had grown used to at Chirk, or what she had anticipated for her married future.

‘But you can’t just say that!’ my mother says anxiously. ‘Of course it was run down, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t beautiful. You ought to say how thrilled I was when your father took me for my first walk on the hill, and we could see the House below us. You must say something! Not just that I thought it was shabby.’

This was the moment at which my mother’s fondness for the solemn, old-fashioned man she had chosen to marry deepened into love. Enthusiastically, she began to lay plans for a herd of Ayrshire cows, to ponder where they would keep horses, and what sort of hens would make the best breeders. The flirtatious tone of her earlier letters gave way to real tenderness. Together, she told George, they would make a splendid team. ‘It will be such fun! Such fun together, won’t it darling.’

‘I meant it, you know,’ my mother says, blinking her eyes and hunting for a tissue. ‘It was so touching. I’d never met anybody who loved a place so much. I never have. Well – you know how he was.’

We both know how he was. I’m glad to look into his diary and find this insecure and unfulfilled young man – he was just twenty-three and looked less in his round schoolboy spectacles – declaring that he had found happiness at last, with the prospect of bringing together the two things he most adored. ‘I must be the luckiest man in the world,’ he wrote.

Love, however overwhelming, placed no curb on my father’s snobbery. It gave him a sense of singular joy on 4 March 1946 (‘the very great day’) to see that the official announcement of their engagement took top place in The Times gazette, ‘at the head of the column!’ It tormented him that the announcement came too late for his name to be added to my mother’s invitation to a ball at Buckingham Palace. My father became as avid as Mr Pooter, one of his favourite fictional characters, for details of this elegant occasion. (It horrified him that my mother did not make a special visit to the hairdresser or even have a manicure.) To whom had she sat next at dinner, he wanted to know? What kind of china and glasses had been used? And what had the young princesses worn? But my mother, who took little interest in such details, could only remember that the food had been tepid. He was comforted a few weeks later when the two of them shared a dinner table with Princess Elizabeth – among twenty others – for a dance. George seized the opportunity to take a good look at his royal neighbour. She was pretty, he conceded, but not a patch on his Rosebud, ‘by far the loveliest woman in the room.’

Love coloured everything. He had, until now, shown no taste for classical music; now, when he visited his parents for an occasional weekend, they were amazed to hear Liszt and Bartók crackling down the staircase from the portable player in their son’s room. The very mention of ballet, in later life, was enough to curl his lip; three weeks before his wedding, seated in the stalls of Covent Garden for a performance of Sleeping Beauty, George was in a state of entranced joy. ‘It was heaven: the music, the dancing, the decor all lovely – and my adored Rosebud sitting beside me looking like a dream.’ He wanted the world to share his awareness of her beauty; if not the world, his entire family. Thrilled by the chance to show his prize off to his grandest relations, he paid twenty pounds for tickets to a charity ball at Euston Hall and fancied they might be asked to stay the night. No invitation came, although my parents were the last to leave.

The visit to Euston spurred him to enliven their long journey home with reminders of his royal connections. Rosemary’s family were fine, to be sure, but who could cap the glory of claiming Charles II for an ancestor? (A considerable number, if we are to be honest, after a span of seven generations; to my father, however, the cherished connection had grown close enough for him to thank goodness, for Rosemary’s sake, that he had not inherited the king’s lax morals.)

My father was in ecstasy; his fiancée was in a state of nervous exhaustion. ‘Those endless visits to relations!’ she groans. ‘Aunt this and cousin that – it never stopped. I never knew a man with so many cousins. And all the worry about how I dressed: I’m sure the FitzRoys couldn’t have cared less which hat I wore to church.’

‘It was the way he showed his pride. Come on, Ma, you know he was wild about you. And your family: what did they make of him?’

‘They thought he was all right.’ She fidgets. ‘He hadn’t read much. At Chirk, we were always talking about books and music and things. George didn’t have a lot to say, except about family history.’ She pauses to think, anxious not to sound too harsh. ‘I mean, there was Thrumpton, and the wedding plans, and his new car – such a wretched thing. An Alvis.’

I know about this. ‘You made him buy it. You certainly paid for it. It’s always described as yours.’

She looks baffled. ‘But I didn’t drive.’

‘Then you bought it for him. It’s not a crime to have been generous.’

‘Horrid car,’ she says with feeling. ‘It never stopped breaking down and you know how useless your father was at mechanical things. That’s why he found it so useful later to—’

Breaking off, she gives me a sideways look. ‘You know. Have a friend.’

The difficulty about holding these conversations with my mother is that I never know which way she’ll want them to go. It’s apparent that she’s in the mood today to discuss the years in which we lost him. I’m not.

‘I’m longing to know more about the honeymoon,’ I say.

‘I’m sure you are.’ Her tone is drily discouraging.

‘I didn’t expect to find you going off to a film on the first night of your marriage. Do you remember? You were staying at the Savoy as a present from your parents. That must have been fun: I’d love to stay there.’

Babble babble. I’m prattling while I bait my trap, hoping she’ll fall into a web of compliments and tell me: why. Why did my parents go to a silly costume drama (the young Gene Tierney and Vincent Price in Dragonwyck) when they could have been behind doors and locked in each other’s arms, bruising their lips with newly legitimised kisses? Standing above her in the half-light of the curtained library, I stare down, willing her to read my thoughts. Her fingers are plaited together and she’s looking at them intently, circling her thumbs around each other. There’s earth under her nails and the cheerful red varnish has chipped away from the rims. Her hands have looked this way for as long as I can remember.

‘Shall I open some wine? We could have a glass before supper.’

‘I don’t want any,’ she says in a low voice, then glances up at me. ‘I haven’t objected to your writing this book. I haven’t tried to stop you, have I?’

‘Not yet!’

She doesn’t smile. ‘You don’t have to put in everything. I’ve read your biographies. You didn’t say what Henry James did in bed, or Mary Shelley.’

‘They weren’t around to tell me, but you . . .’ Eagerly, I rattle off a quote from one of her own letters, forgetting that this is a sure way to antagonise an interviewee, let alone a mother. ‘You called him “my clever, mathematical, neat, precise and altogether perfect person”, and that was just two weeks before the honeymoon! It’s not passionate. You must admit that.’

‘Letters don’t tell you everything.’ Her voice is still so low that I have to bend to hear her. ‘All that side of things was lovely. It always was. Can’t you just leave it at that?’

No, I can’t, I want to shout. I need to know. Lovely, in what way? Lovely, because of what? But she’s slipped away from me, back behind the door she keeps closed on anything unpleasant. I’m my father’s daughter in my volatility and imperiousness; each time we talk, I see more clearly that she is hers in the way that she protects herself from intruders and their judgments.

Staring down in thwarted silence at her bent head, I remember the time I first made love and how, full of glee and complacency on a summer day, I tracked my mother through the garden shrubberies to boast about it. Nothing much had happened – the affair was over in less than a month – but I glowed with foolish pride that afternoon. My body was hot with remembered pleasure; my mind shimmered with the memory of tangled limbs, smothering kisses. Kept down for so long in a state of lowered confidence, I had my parents beat at last. I’d discovered things they could never have dreamed about. I told it all in triumph as she stood there, looking smaller than myself, trowel in hand. The words came rushing from my mouth as I searched my mother’s face for – what? Wonder, I suppose, wonder and envy.

What I did not anticipate was the outstretched hand, the gleam of sudden secret pleasure in her eyes. And wasn’t it marvellous, she said, when—

Horrified, I cut her off and backed away. I wanted her to be abashed by my revelations. I wanted none from her, a middle-aged woman, an untouchable in the hard eyes of youth. I didn’t see, as I do now, the generosity and warmth of her response.

And now, when I want so badly to uncover her sexual feelings, there’s no way to get at them. The door has been tight shut. It was lovely. It was always lovely.

I’ll have to continue my interrogation another day.

They were married at St Margaret’s Westminster in June 1946 (‘509 guests!’ my father noted, rejoicing at the lavish number of wedding cheques he had received). Since foreign travel was still prohibited, their prolonged honeymoon was taken in Britain. In Wales, they spent a fortnight at one of Tommy Howard de Walden’s properties, a seventeenth-century house called Plas Llannina. The summer was a scorching one, too hot for excursions until the end of the day, when they strolled along the beach towards New Quay, past the spot where my mother remembered having seen Augustus John stretched out on the stony shore like a beached whale after emptying a decanter of whisky with her father, his host. Coming back, they peered into the semi-derelict applestore where Dylan Thomas lived while he began to dream up the story of Milk Wood. With the oil lamps lit, they sat reading each other chapters from old-fashioned novels about foxhunting—

‘Seriously?’

‘Why? Any objections? You haven’t become one of those activists, have you?’ my mother inquires with sudden suspicion.

‘It sounds so unlikely.’

‘Not at all.’ My mother is her jaunty self again this morning. ‘It just goes to show how little you really know about your parents.’

Snugly tucked up in a big double bed, with the oak door shut against the creaks and whispers of a house more haunted than any other my mother can remember, they opened the window to gaze at a full moon above the sea and to listen for the bells that, so the stories went, rang up from Llannina’s submerged church to warn of coming storms.

‘And don’t forget Valentia.’ She sighs. ‘Such views: I’ve always meant to go back there.’

My father’s diary tells me less about the little rainswept island lying to the west of County Kerry than can be gleaned from a couple of internet sites; one entry does record that my parents spent time ‘very pleasantly’ in their hotel room. Does ‘pleasantly’ hint at unmentioned pleasures? I can’t tell and my mother can’t – or won’t – remember. It’s easier to pick up the note of outrage in his account of a visit to the skeletal ruins of a Kerry mansion, burnt out by a careless smoker on a wild weekend in the twenties. My father was too upset to eat his supper that night. Emotion, as he unfailingly reminded us in later years, went straight to his stomach, proof of his exceptional sensitivity.

Hints of troubles to come surfaced in August, when my parents were in Norfolk with George’s parents, enjoying the last sleepy days of a glorious summer. (‘They seem so entirely happy,’ his mother noted, adding that she was glad Rosemary seemed to be a fit and energetic young woman. George’s health must be carefully watched, Vita warned her daughter-in-law. This project of farming was all very well, but poor George was too delicate to undertake more than the lightest tasks. Advising and overseeing were his real strengths.)

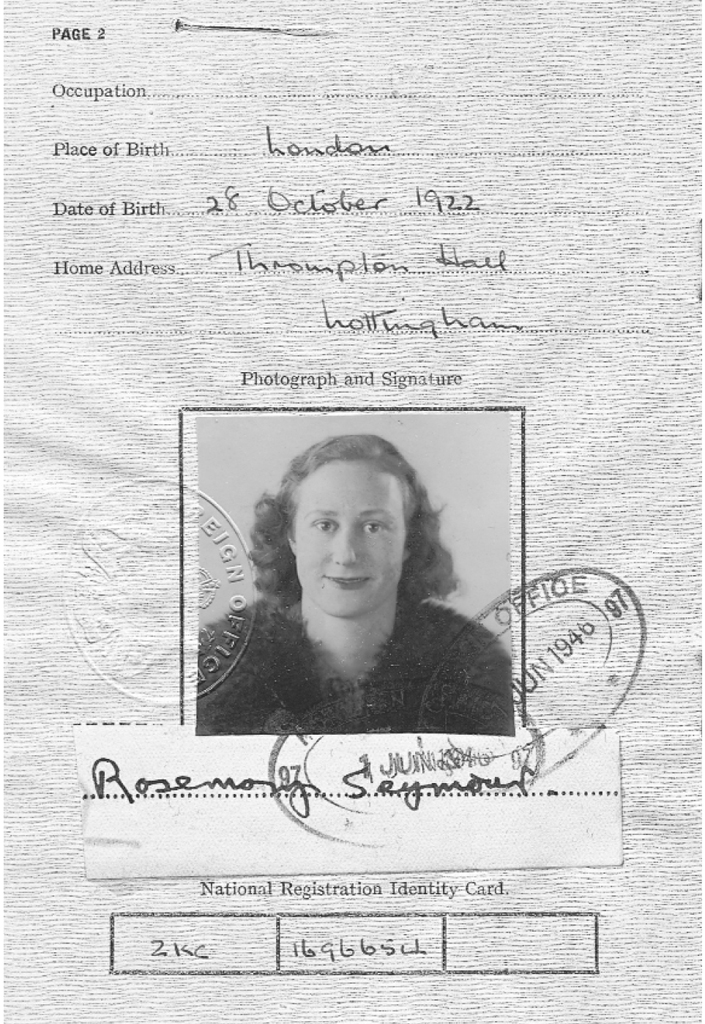

My parents needed identity cards for their honeymoon off the coast of Ireland in 1946.

A letter from Charlie Byron cast a sudden chill upon the pleasant experience of admiring a last magnificent clutch of wedding presents. (My father had been shameless in advertising his need for furniture and paintings of a kind appropriate to his future home.) Capricious until the end of his days, Charlie was reviewing his plans once again and wondering if he had been too generous to his nephew, too hard on his Byron cousins. Perhaps, he wrote now, George imagined that the Home Farm and the Lodge were being given to him for nothing? He had better take note, now and for the future: no special privileges were being offered. He would be expected to come to financial terms with the land agents – ‘and ME!’ the old man wrote in shaking capital letters, forgetting that the proposal for George to run the estate farm had come from himself.

Vita was alarmed by the letter – perhaps Charlie was planning to leave his home to those Byron cousins, after all? My father was irritated, but not unduly worried. Charlie had changed his mind before and would doubtless do so again; at the end of the day, the only surviving Byron claimant was a Catholic and Charlie Byron would not even let a Catholic through his door. True, my father would have preferred to hear he was going to inherit the House outright, but a life tenancy still secured his future. Charlie, he told his mother, was just playing games.

Overall, as my father settled into his new life as a young farmer with a pretty little manor house in the village he adored, his situation was enviable. Rosemary’s relaxed attitude to money was due to her possession of a substantial amount of it, to be shared with him; her parents were both fond and lavish. They had helped to find a young Scot who was willing to oversee the Home Farm; three girls from Chirk village were persuaded to come and form a domestic household at Thrumpton Lodge. Anna scurried around to find them a chauffeur, a dairyman and a day-labourer. The final feather in my father’s cap was the news that Margot Howard de Walden’s personal maid wanted to return to her Nottinghamshire roots. Word arrived that she had settled in a nearby village, on hand to sew, press clothes and pack cases. The level of elegance at Thrumpton Lodge was now, as George joyously noted, almost ducal.

At twenty-three, then, my parents were fitted out for a life of unusual comfort. When my mother, misty-eyed, talks of her farming years, I want to know how many farmers’ wives had a chauffeur-driven Daimler in 1947; unkindly, I comment that she reminds me of Marie Antoinette tending vegetables behind the Petit Trianon.

They kept no diaries during the four years they lived at The Lodge; my mother remembers these as the happiest of her married life, marred only by a requirement to dine with the old Byrons at least twice a week. This, as George’s uncle began to slip into senility and Anna grew correspondingly fretful, was not a cheerful experience.

My mother believes her memories. She remembers creating a pretty garden at the Lodge (‘I put in those borders!’) and a cheerful home. (‘All the family loved coming there. The Lodge was such a cosy place.’) The meagre documentation that has survived shows this to have been a period of dismay, confusion and enforced economy. Can both be true?

The main agent of change was the unexpected death of Tommy Howard de Walden within months of his youngest daughter’s marriage. That June, Rosemary noted how ebullient her father seemed, as if he had already managed to put the memory of Chirk behind him. In September, she worried that he was looking tired. In October, he was taken into the London Clinic for an operation. On 5 November, a date she has ever since associated with misfortune, her father died. He was sixty-six. The given cause was jaundice.

George Seymour had married a young woman whose income greatly exceeded his own. In the late autumn of 1946, at the beginning of the coldest winter in living memory, when snow buried the hedges from view and the roads around Thrumpton were blocked off as impassable, bad news came in. Tommy Howard de Walden had never liked lawyers; convinced that they were out to rob him, he had put off the unpleasant business of dealing with them. As a result, scant provision had been made for his five daughters. My mother and her older sisters were no longer heiresses; instead, to his dismay, my father found himself married to a young woman whose means were almost as modest as his own.

‘I will take care of you forever,’ George had promised Rosemary at the beginning of the year. He had not imagined that this would involve economic support. Eleven months later, preparing to celebrate a family Christmas at Thrumpton Lodge to which he had proudly invited his parents, his married siblings and their children, my father had to beg for a delay in paying the fuel bills. His plans to buy three young pigs for the Home Farm were cancelled.

I have said that I would not want to be in a wartime trench with my father; I’m proud to see how well he performed in less dangerous circumstances. The Christmas plans went smoothly forward; Vita praised her son’s generosity as a host and scolded him for buying such lavish presents: a pair of crystal vases for herself and a really beautiful cocktail frock, off the peg, that might have been made just for Rosemary. Vita had no idea that her son had paid for these Christmas gifts, and the traditional turkey, by cancelling his order for a new suit – his own was threadbare – and recalling the deposit.

‘I’m a fool about money,’ my mother had blithely announced in one of her early letters; my father now began to discover that she was, indeed, an innocent. Arithmetic had never been her strength; she understood only that her bank statements must always show her account to be in credit. Asked by her husband to perform some simple feat of addition, Rosemary gladly offered a prompt answer. Unfortunately, she had halved the sum instead of doubling it.

George could not, it was plain, rely on his wife for the keeping of ledgers and cash books, by which he hoped to control their rapidly shrinking funds. All accounts, bank details and household reckonings would, from this time on, lie in his province.

I was scornful when I first encountered the Telephone Ledger. Begun a month after my grandfather’s death, the ledger-book was maintained, with only one break, until a few years short of my father’s death. I looked at it, initially, as a potential hiding place for awkward secrets. ‘Black Boy’ sounded promising; so did three entries for ‘artificial insemination’.

Closer inspection showed that the ledger had no shocks to offer. The Black Boy was the name of a pleasantly old-fashioned hotel in the centre of Nottingham; the entries on artificial insemination referred, not to procreational difficulties between my parents, but to the herd of Ayrshire cows they had purchased, at £70 a head, during the first ambitious weeks of taking on the farm.

The entries told me little that I did not expect; there was no surprise in finding that each call to a person of illustrious birth was fully recorded, with titles, while those of less genealogical interest were briskly noted by their surnames. The unexpected aspect was that the entries had been maintained, with a note of the length of time spent and subsequent cost of every call, over a period of fifty years. The ledger brought into question the haste with which I had dismissed my father’s service to Barclays Bank (such meticulousness, such dedication, could not have gone unremarked). The ledger showed me that, despite the capriciousness with which my mother had once held him in thrall, my father now controlled the marriage.

My father’s entire life had been driven by his passion for Charlie Byron’s home. I wonder what was in his mind in 1948, when he made a visit to another Byron landmark in the neighbourhood. Newstead Abbey was where his uncle’s celebrated ancestor had spent his youth; since then, it had become a desolate ruin. Was my father thinking about Thrumpton as he peered through the Abbey’s grimy windows at dusty wooden floors, peeling wallpaper, sheeted furniture? Was he wondering, for the first time in a lifetime of obsessive love, if a neglected, inconvenient old house, in which his children would never have the right to live, was worth the wait?

My father’s feelings were about to be severely tested. The following year, in a glorious June, Charlie Byron died. It was not, at this point, apparent just how little he had done to safeguard his family property.