![]()

FAMILY SNAPS

‘Miranda is so completely happy up there,’ my grandmother wrote to my father in 1952, the year my brother was born. Vita, while staying at the House, had visited the nursery – the same that had once served as my father’s – on the top floor.

I don’t remember this occasion. I do remember crying when I was taken away from a more comforting room, my home for the first year that we spent there, in the lower part of the House.

To a small child, the House was not welcoming. When I described my father’s early days there, I was drawing on my own fear-laden memories. The Byrons, with no children of their own, had made no provisions for reassurance or comfort. The top floor of the House, when I arrived, was as it had been in the 1920s, a chilly, desolate region, shut off behind doors.

Later, after the birth of my brother, our parents tried to brighten the garret-like rooms and narrow passages. My bedroom walls were papered with garlands of roses; the nursery acquired a tall bookcase, an electric fire, a rocking chair and a big, old-fashioned doll’s house with rooms large enough for a small child to hide in. To a visitor, climbing the stairs from below, the children’s wing must have seemed cheerful enough.

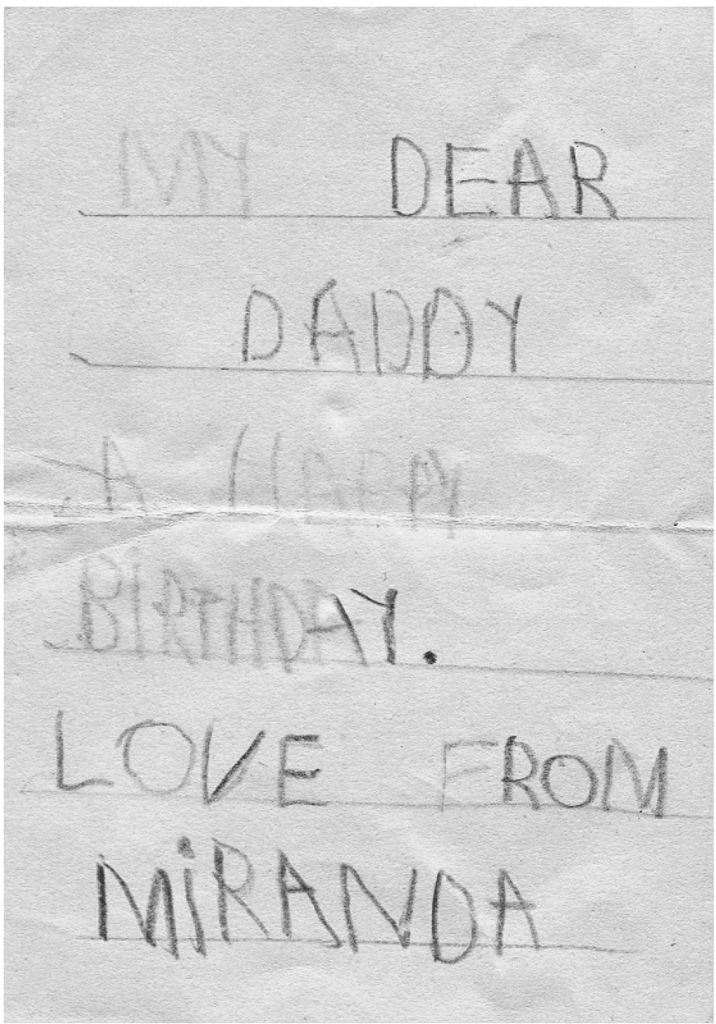

A birthday note delivered from the top floor.

‘We’d have kept you nearer if we could,’ my mother says. ‘But there wasn’t any room, not with a nanny and nursemaid. And you were happy. Don’t go pretending you weren’t. You never stopped reading! Whenever I came upstairs, you were always sitting by the bookcase.’ I ask her if she remembers the time – I can still see her turn and go crying down the stairs – when she asked if she might take me into the garden at some hour that had not been previously arranged. The nanny, even though she did not particularly like me, grasped my hand and squeezed it. (‘Whose little girl are you?’ Squeeze. ‘I’m Nanny’s little girl. I want to stay with Nanny!’)

‘Nasty little thing,’ my mother says. And she does, for a moment, after fifty odd years, still look distressed. ‘Why would you ever say something like that?’

I’ve no idea. I only remember the pleasure it gave me to see that I could cause pain to a parent, somebody who seemed, at that thwarted age, so beyond my reach. ‘I think’, I say, ‘I wanted to punish somebody. I was so scared.’

‘Scared!’ My mother puts on her sensible face, the face of a woman who has no truck with terrors. ‘What nonsense you talk! What did you think was going to happen?’

‘I didn’t know. That was what frightened me so much. I never knew.’

Three terrors ruled life on the top floor: ghosts, fire and floods.

The ghosts, as I now know, were imaginary. Then, however, I had complete faith in my father’s story of the pregnant housemaid who hanged herself from a skylight outside the little room in which he, a quarter of a century later, would sleep. My father had been subjected to this story himself; the room in which he had shuddered was now mine. (No record, other than the testimony offered by my father, suggests that a hanging actually took place.) Like my parent before me, I felt the ethereal housemaid’s soft skirt brush the back of my neck each time I went down the four steps beneath the skylight; like him, I heard her weeping in the night, whenever the wind was up, and trembled.

I had other companions as well, of my own making. I believed in a sharp-faced, skinny-tailed devil who pressed his face to my window each night after the curtains were drawn, hoping that I might have forgotten to shout, before I jumped into bed and pulled the sheet up over my head: ‘Get thee behind me, Satan!’ I believed in witches who hid in the garlands of roses strewn across my newly papered bedroom wall. (Poor sight helped to foster this delusion.) I believed in the power of the moon to strike me and lay me under a spell.

If, during the long night, I wanted to visit the lavatory, I had first to pass through the hanged housemaid and then, after opening the door on to the high carved staircase, dodge past the long, treacherous moonspokes that barred the way to the top floor’s only watercloset. Bedwetting, although frowned on, often seemed preferable.

But pictures present a different story; here, I look extremely cheerful in my new party dress.

Fire, fear of it bred in him by his uncle, was my father’s greatest terror.

Years later, laughing, he told me about Sammy FitzRoy’s visit to the House in 1928, when he himself was five years old. Sammy, Anna’s wild younger brother, was in unusually subdued spirits: never lucky, he had just burned down a house – his own mother’s – by dropping a lighted cigarette. Charlie Byron, frantic with alarm, imposed a smoking ban during his stay at Thrumpton; Sammy, for the first six hours of his visit, was the model of abstinence.

A pre-dinner glass of sherry brought on the crucial return of the urge. Sammy felt for a cigarette, remembered orders, shook his head, looked firmly around the room and announced that he was in need of a rest. An hour later, climbing the stairs to bed, my father encountered his uncle Charlie kneeling outside Sammy’s bedroom door, nose to the keyhole, hands clasped, as if engaged in prayer. (Which, as a devout clergyman, he may well have been.) This performance was repeated, every evening, for a week before Sammy, bored with frightening an old man out of his wits, called for his car and left.

I’m not sure whether my father realised how close his own behaviour came to that of his uncle. I witnessed him undertaking precisely this ceremony whenever my brother or I invited any smokers to stay. If caught hovering outside one of their bedrooms, he was unembarrassed and unrepentant. The House, and its safety, came first.

The burning of Nuthall Temple was the first fire I heard about. Described by my father with horror – what could be more wicked than the wanton destruction of a family home! – it took on the proportions of a mythic devastation. A gaudy oil painting by Frank Brangwyn (or someone who admired his style) hung on the flight of stairs leading to the top of the House. It showed flames belching out of a black fortress, with figures streaking across the canvas in front of them, orange-tipped by the firelight. This, I supposed, was the Temple.

I had never visited the site of the Temple. All I knew was that it had burned to the ground in the course of an afternoon. If a stone temple could be destroyed in a couple of hours, little imagination was needed to guess how quickly a house like our own, comprised largely of wood, plaster and brick, could be reduced to ashes.

Fire threatened our lives. Fire kept our household warm. The windows of the House looked out upon country fields, but this was also coal country, ten miles from the notorious pits of D. H. Lawrence’s Eastwood. Sometimes, sitting beside my father for the half-hour before bedtime when he would read aloud from The Pickwick Papers, I might see a glowing lump of coal jump the low brass fender and land upon the library carpet. My father always noted it in time, but what, I wondered, if nobody had been watching? What if the fireguard were one time forgotten, or if it should fail to prevent the leap of a smouldering fragment?

Mrs Bardell shrilled with fright at Mr Pickwick’s innocent invasion of her bedroom; I couldn’t pay attention. Fiery tongues were already licking their way across the carpet to the bookshelves and out towards the closed door. The encyclopedia in the nursery bookcase had informed me that fire burns through a seasoned plank of timber in just four minutes. In four minutes, the flames would be past the library door and enfolding the fruit-crowned wooden pillars at the foot of the staircase that climbed all the way up to the last oak door that shut off the nursery wing and the sleepers who lay trapped inside it.

We, my brother and I, would burn in our beds.

Not true, my mother says. We children were never in danger. We had The Chute.

The Chute, hacked out of a thick interior wall on the recommendation of the local fire department, led directly from my bedroom into our nanny’s bedroom cupboard. Here, it was imagined that Nanny, neatly dressed and ready for action in any emergency, would receive her little charges with open arms and carry them down a blazing staircase to safety.

I had no faith in this scenario. Nanny, a gaunt, anxious, passionate woman with the improbable name of Ruby Rose, often expressed the wish that she might have a little boy of her own. She didn’t feel the same way about girls. My brother was clear-eyed and pink-skinned. He had a mischievous smile and a mop of flax-yellow hair. I knew which of us Nanny Rose would save.

Our parents were not unloving; they certainly had no wish for their children to burn. Further precautions were eventually taken. An iron bar was attached to the nursery windowsill. Inside the window, a hemp rope lay coiled, neat as a cobra within its wooden box, long enough to stretch three storeys down to the flagstones at the foot of the House. Today, I wonder whether either that box or that rope could have survived a fire; at the time, all we objected to was the sensation of coarse hempstrands rubbing our tender thighs and clenched palms raw as we practised the descent, drilling against our father’s stopwatch. (Later, despatched to a school that rated pupils by their ability to saddle up a horse or hurl a ball through a ring, I shone at the gym exercise that required skill in rope climbing.)

My father’s terror of fire conflicted with his aesthetic views. He was terrified of a fire; still, he could not bring himself to get rid of the old flexes, plugs and fittings that had been part of the House for over seventy years. They reminded him, he said, of its golden age. At the time of his death, most of the electric fittings spat blue flame when they were connected to plugs. Edwardian flexes, long stripped down to naked wire, trailed potential firelines across the wooden floors. One bulb, still burning dimly at the dark end of a passage, had 1926 printed on the underswell of its globe.

Water held even more terror than fire. In books of mythology, I read about Neptune, who struck the earth with his trident to raise the floods. Rivers raced across the plains, and waves lapped the mountain peaks, until all was a shoreless sea and fish swam in the branches of the trees in the woods.

Water rose from the dreams of my childhood like a smiling thief, stifling each room in turn with clammy outstretched fingers, filling the cupboards and drawers with the stench of river mud, burying the House as deeply as the trunks of tall willows that are sealed from sight by a sudden tide of winter floodwater, the whole reflecting, at its loveliest hour, the salmon blush of early evening, of twilight at Thrumpton.

Our parents were not unloving: here, I help my mother to steady the old-fashioned perambulator which holds my younger brother.

Fire, like ghosts, lived in the dark world of nightmare. Water was real. Each winter, as the river spilled over its banks and joined the lake, water seeped up from the earth and into the warren of cellars beneath the House, spreading a net of slime below the polished floors of orderly rooms. This was the season in which the smell of death taunted the ceremonious life of the House with the impolite stink of rotting fish.

This, in earlier times, was when the House’s owners took long, quiet holidays on the Riviera, for the protection of their lungs.

The life of our ritual afternoon walks was changed by floodtime. To the west of the House, the flat fields lay under a surface of grey silk, a shroud for the puffed corpses of rabbits that had been either drowned or poisoned by hostile farmers. Walking carefully on the hillside above this seasonal lake, my brother and I avoided looking at the bobbing bodies. Instead, we admired the high clumps of yellow bubbles that danced across the surface of the floodwater. We thought of these billowy products of pollution as pretty playthings. Watching the waters spread, we imagined the House as an ark, ourselves as its crew.

Once, escaping from the House, the two of us strayed off the village road, down to the river, and into flooded pastureland. Trying to turn back, we found we could not stir. Greedy river currents sucked and swirled around us, pouring grey water into the funnels of our small rubber boots, holding us fast, as if under some spell. Wailing, we reached towards the high bare hands of the willow branches at the edge of the field, begging them to bend and to save us.

Eventually, the pasture-owner waded in and scooped us up, a howling child pressed each to a broad hip, as he strode back to land and up the drive to the House.

Afterwards, we talked about our escape. Would our father have ventured into a flooded field to rescue us? We were unsure.

In the event, we found we had never been missed.

Water was at its most bewitching in the landlocked Midlands during the deceivingly brief season of high summer and parched fields, when a stroll beside the river brought cooling thoughts. This was when my brother and I wandered down to the far end of the park. Here, at the foot of a cliff of red clay, lay a secret world: a small marina, complete with lock, bridge and a sweetshop selling aniseed balls and fizzy lemonade. Here, hours slipped past as easily as the trickle of licked ice cream while we watched the lock gates swing closed and the watery pit begin to surge, bringing a bargeload of cheerful river-travellers up to the level of the path. Red-checked curtains twitched forward to mask the cabin rooms from sight; saucepans rattled; glasses clinked. Hungrily, we watched the bargees chug away, adventurous and free.

Watching life on the canal, I imagined it winding away to flamingo-bordered, cobalt blue lakes, and to undulant turquoise seas that might spread their lapping waters to the earth’s far continents. (Fed with Fifties-style colour postcards from the travels of our parents, my brother and I pictured the larger world in bilious enamel tints.) Digging a hole, after the flood had receded, in the gravelled laundry yard at the back of the House, I was hoping, quite soon, to reach Australia.

I sit on my father’s knee for a family snap with Dick and Vita, who is trying to hold my brother still.

Familiarity with the power of floods, increased by our adventure in the farmer’s field, bred a respect for water that bordered on terror. I didn’t mind paddling when our parents took us on summer visits to the seaside; I screamed if anybody tried to coax me further than the water’s edge, out to the point where the sand sheered away and nothing lay below but the sucking depths, cold as the clasp of mermaid’s hands.

My introduction to swimming as a pleasure came with the arrival at the House of Slav, who was both fond of children and good at swimming.

Slav was an Ethiopian. He had been castrated and sold, so he told us, as a slave in the market of Addis Ababa. Bought by an Englishman for unspecified use and taken to Southport, he escaped at the earliest opportunity. We never heard what happened next. Slav did not like questions about his past. What he did like, he made abundantly clear from the very start, was the personal freedom of physical nudity.

Slav arrived on a bicycle, one summer afternoon, clad only in a khaki shirt and, in a temporary concession to propriety, a thin pair of shorts. He knocked at the back door, introducing himself by his first name – we would know him by no other – and asked for work. He took pains to emphasise that he expected in return little more than his bed and board. My mother was doubtful; my father, keen for cheap workers, was enthusiastic. Slav was hired, on the condition – this was laid down by Nanny Rose – that he would always wear, at a bare minimum, a loincloth, while working in the House. My mother, after some thought, produced the remnants of a silk dressing-gown that dated back to her family’s visit to King Farouk. Egypt, surely, wasn’t too far from Ethiopia? Slav wore his loincloth dutifully, but without any show of pleasure.

The presence of our new employee caused talk in the neighbourhood. My father had, until this point, been regarded as faultlessly conventional. The arrival in the household of such an outlandish figure brought his reputation into question. Did gentlemen employ such people for normal reasons? What, precisely, was Slav’s function?

This, so far as I am aware, was the first taste the neighbours were to receive of my father’s waspish humour. A Baron de Charlus might have appreciated it, but this was the Midlands in the late Fifties and such sense of humour as the majority of my parents’ country neighbours possessed was uncomplicated by wit.

On a fine July day, a lunch was held. The dining room blinds were drawn; my father, masked by dark glasses at the head of the table, proclaimed a headache. Plunged into a yellow gloom, the guests exchanged desultory chat and did their best not to stare too eagerly every time the door from the kitchen swung open.

Time ticked away; nothing out of the ordinary had transpired. Glances were exchanged, followed by knowing nods, indicating that the guests believed they had, perhaps, been led up a garden path. Conversation grew louder and less deferential.

Then, as coffee was announced, my father walked idly towards the window and snapped up the blinds. The gasp from behind must have given him as much pleasure as had the planning of the scene now unveiled. For there, stalking across the lawn, in all his (possibly unselfconscious) glory, strode our tall, beautiful, coffee-brown Slav, a tiny watering-can dangling from his fingers, a shred of yellow and scarlet silk knotted about his naked hips. The pretence of his engagement at a task was quite perfunctory.

In retrospect, and in the light of my father’s obsession with physical appearance, Slav must have provided him with an aesthetic pleasure that compensated for the fact that, as time went on, he showed increasing reluctance to actually do anything. Observing him from one of my many hideouts – a clump of bamboos; a laurel thicket; the lower boughs of a densely covered ilex, or holm oak – I watched Slav strolling to and fro across the lawns, doing nothing except, with no personal effort, to look magnificent. Sometimes, looking past him to the House, I would see a shadow etched on one of the library blinds. Behind it, my father sat at his desk, writing a letter or, perhaps, simply gazing at the figure on the lawn.

Too young to understand what castration meant, I asked Slav to explain it. He did so, at length and without embarrassment. Castration could affect you in two ways, he told me. For most men, the result was a high-pitched voice, like a lady’s. For him, the operation had produced only extreme sensitivity to temperature. This was his reason for not liking to wear many clothes. But what about the winter, I asked? If he grew very hot in summer, didn’t it follow that he would grow very cold in the winter? Why, then, did he wear just as few clothes in December? But Slav, who had a proud, capricious streak, grew suddenly bored with the conversation. Closing his eyes slowly and looking, to my admiring eyes, more than ever like a beautiful marching soldier from Darius I’s army in my history picture-book, he walked away.

Slav was as sensual in his pleasures as a cat. In winter, he liked to roll naked in snow; in summer, he waded, without a stitch on, into the lake and swam sleekly up and down, his head held high above the water, like a ship’s prow. Watching him one day, I admitted that I was scared of water. Slav smiled sleepily and suggested that I get my bathing suit.

Being lifted on to Slav’s shoulders and carried down the grass bank, out into the dark water, was the most delicious sensation I had yet known. Even so, I panicked as he pushed my legs away from his chest and out into the treacle-dark lake. Still clasped by strong hands, I flailed and choked and floundered – and found, to my surprise, that I had reached the rushes. Clutching them and kicking while I cried with fear, I raised up my legs to level with the frantic paddling feet of a startled coot.

‘You’re there!’ said Slav, and pulled me back to try again.

One afternoon, two years after his arrival, my parents, my brother and I walked up the village street to watch the home team play cricket on the field they called Twentylands. The pitch lay close to the road, enabling us all to see, as the batsmen paused to change ends, that Slav, wearing his shirt and khaki shorts, topped off, on this occasion, by one of my father’s panama hats, was bicycling gracefully past. This was surprising – Slav had left his bicycle, untouched, in one of the old disused stables at the back of the House, since his arrival. Comfortably, my mother suggested that he must be trying to get his weight down. (Slav, although still elegant, was no longer so lithe as he had been on his arrival, possibly because Nanny Rose had taken to baking him a weekly batch of scones.)

Perhaps Slav heard my mother’s words and took offence. The House, when we returned from the match, was empty. Slav had left a bundle of possessions behind, but he never came for them. He had gone, without warning, as suddenly as he came. We hadn’t, until then, realised how much he had become a part of our lives. Nanny Rose remarked that the House seemed quite empty without Slav about the place. Peeping out across the lawns from my hideout in the bamboos, I closed my eyes to slits, willing one of the long straight shadows to turn into the silhouette of my hero.

My father was quite irritable after Slav’s departure.

The hat that Slav had taken away, he explained, was one to which he had been particularly attached.

To my eyes, one panama hat was much the same as another. But there was only one Slav.

I am sorry, both for the reader and myself, that no photograph of Slav has survived. My mother says that he did not care to be photographed.

Everything in the House leads back to the lake.

Up above the top floor, a steep staircase leads to the roof, and a walkway hidden behind the gables. Above it, accessible by scrambling up a gutter, a square platform of lead, bleached pale as birch-bark by a century of sunlight, overlooks the landscape.

The Turn of the Screw is a story I always connect to the House. It does, however, have a flaw. Henry James, bringing the governess back from one of her first strolls outside Bly, the country house to which she has been despatched, makes her look up. She has to do so, in order to see the ghost of the dead butler, Peter Quint, defying her from the rooftop. As a dramatic scheme, it works; in real life, it’s implausible. People, unless called to do so, look ahead, not up. A roof is the place to go, not to exhibit oneself, but for concealment.

From the high platform, my refuge through all the years of my father’s life, the view stretches out to the distant railway line, where it spans the river, beyond a hill massed thick with beeches. Come back. Follow the slow snake of the river to its bowstring tributary, the lake. Perched up here on the leads, you can watch a world of activity below: herons staking out their watchpoints in the rushes, cormorants balancing on treetops, swans skimming low enough to ruffle their own reflections. From here on the roof, all is visible.

Looking down now, I might see myself being carried out into the water on Slav’s shoulders. I might, but I don’t. What I see is always the same. I see my father.

He’s sitting on the bank, the boy from London at his side. The long plumes of the willows overhang them and keep the bright sun away. My father is reading aloud, from one of the old-fashioned humorous novelists that his own father relied on to keep sadness at bay. The boy is leaning forward, laughing and enjoying himself. My father’s arm isn’t quite touching his.

Here’s happiness and ease. Here’s what he never found with us.

I’d be frightened now to look at my own face, or to hear my own voice, when I hid up on the roof, spying on the usurper, hating them both. My screams sounded so ugly that I’d put my hands over my ears to keep them out. It shocks me, today, even to acknowledge that the screams of an angry, jealous child were still coming out of my mouth when childhood had long been left behind.