2

The Firebrand

VERSAILLES AND AFTER

In a Germany rocked by revolutionary unrest, ravaged by influenza and malnutrition, and dismayed by the abdication of the Kaiser, a feeling of numb bewilderment greeted the signing of the armistice. Ordinary German civilians had been unaware of the dramatic course of events, both military and diplomatic, since July 1918. They could not comprehend why the armistice had been signed while the German Army still occupied parts of France and Belgium. A feeling grew that they had been ‘stabbed in the back’, a sentiment held by all political classes. In November 1918, returning troops were greeted by the citizens of Berlin with flowers and laurel leaves, and a speech from the new chancellor, Friedrich Ebert, in which he declared, ‘I salute you who return unvanquished from the field of battle.’ But many of these men had new battles to fight in postwar Germany. Disconnected from civilian life, they soon joined paramilitary groups, the Freikorps, which the postwar Social Democratic government led by Ebert was to use against Communist revolutionaries.

The feeling of betrayal felt by so many Germans grew when the victorious Allies met in Paris to redraw the map of Europe – and much of the world beyond – a task made all the more urgent by the collapse of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. The principal treaty was signed by the Allies and Germany at the Palace of Versailles on 28 June 1919.

A famous painting by Sir William Orpen captures the moment of signature by the German delegates. In the centre of the frame are the Big Three – the US president, Woodrow Wilson, and prime ministers Lloyd George of the United Kingdom and Georges Clemenceau of France, all three of them serene and exquisitely suited, the victors of the Great War. Clemenceau later observed that Orpen had pictured him sitting between a would-be Napoleon (Lloyd George) and a would-be Christ (Woodrow Wilson).

On this occasion at least, Clemenceau got the better of Jesus Christ, although in the long run it did neither him nor France much good. Stalin had a famous saying, ‘How many divisions has the Pope?’ France, although grievously mauled by four years of war, still had the divisions. But if the war had continued into 1919 and beyond, which many believed it would until the sudden German collapse in the autumn of 1918, then the balance of power would have swung inexorably towards the Americans. However, just as many in the German military believed that they had been stabbed in the back by the armistice, so the French high command was convinced that the German collapse had denied them the crushing victory in the field that in 1918 was rightly theirs.

During the discussion of the peace terms, Lloyd George felt a premonition of the disaster which lay ahead. He observed then:‘If peace were made now, in twenty years’ time the Germans would say what Carthage had said about the First Punic War, namely that they had made this mistake and that mistake, and by better preparation and organisation they would be able to bring about victory next time.’

Nearly all the peace terms imposed at Versailles had been anticipated at the time of the armistice. This was no conference between victors and vanquished. The Germans were merely required to turn up and sign on the dotted line – it was a matter of dotting the ‘I’s and crossing the ‘T’s. Control of coal mines in the Saar was given to the French for fifteen years as compensation for the German wrecking of the mines in north-east France; the east bank of the Rhine was demilitarized to a depth of thirty miles to be occupied by the Allies, also for fifteen years, with Germany paying for the cost of the occupation; conscription in Germany was to be abolished and the size of the German Army limited to one hundred thousand; Germany was stripped of her colonies and denied membership of the League of Nations. The League had been the last of Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points which he outlined in January 1918, and was established to adjudicate international problems.

What really stuck in the craw of Germans of all political persuasions was the Allies’ demand, led by the French, for massive reparations to pay for war damage and the cost of occupation. Germany was to be ‘squeezed until the pips squeak’, according to popular sentiment at the time. In December 1918, the French Minister of Finance, Louis-Lucien Klotz (according to Clemenceau, ‘the only Jew who knows nothing about money’) had made it clear that he expected France’s budgetary deficits to be redeemed then, and in the future, by reparations. At Versailles, France claimed that its total war damages ran to 209,000 million gold francs, and the overall claims of the Allies amounted to approximately 400,000 million francs.

However, sceptical experts at the British Treasury thought that the most that could be squeezed from the Germans would be 75,000 million francs. Eventually the sum to be paid by Germany was left for future negotiations, and in 1932 it was written off. By then irreparable damage had been done. Reparations brought a lasting legacy of hatred in Germany, which was a crucial factor in the rise to power of Hitler and the Nazis – who repudiated Versailles, reparations and all.

After the armistice Hitler focused all his efforts on staying in the Army. In Germany anarchy reigned, and there seemed to be no future in civvy street. He returned to Munich in November 1918 and within a fortnight was one of some one hundred and fifty men assigned to guard duties at the Traunstein camp in Bavaria for Russian prisoners of war. At least there was some stability here as Bavaria drifted towards a civil war which the Social Democrat government in Berlin seemed powerless to prevent.

In Kiel, Berlin and Munich, Socialists assumed local authority, but in the chaotic conditions which prevailed in Germany they were unable to impose order. In Munich, an uneasy Socialist coalition, headed by Kurt Eisner, had been installed and the aged King Ludwig III had fled Bavaria. Over twenty years later Hitler would joke that at least he had the Social Democrats to thank for sparing him the trouble of removing these ‘courtly interests’.

In Munich there had at first been little revolutionary fervour, only a feeling of exhaustion and war-weariness. While Eisner and his colleagues fretted about coaxing the overwhelmingly rural and deeply conservative population of Bavaria into supporting their gradualist experiment in Socialism, the revolutionaries, the so-called Spartacists (Spartakusbund), were ready to move. They seized their opportunity after Eisner was assassinated on 21 February 1919 by Graf Anton von Arco-Valley, a former officer who was studying at Munich University.

At the end of April, a full-blooded revolution proclaimed a ‘Red Republic’, promising ‘a dictatorship of the proletariat’ to be guaranteed by a twenty-thousand-strong ‘Red Army’ led by Rudolf Eglhofer, a twenty-three-year-old veteran of the Kiel mutiny. The declaration was followed by an orgy of murderous reprisals against prisoners of the ‘Red Army’ and brutal counter-reprisals by the so-called ‘White Guards’ Freikorps formations massing outside Munich. Civil war exploded as revolutionaries and reactionaries clashed in street battles which saw both sides employing flame-throwers, heavy artillery and armoured vehicles. Prominent in the fighting was the Freikorps Epp, a formation commanded by Franz Ritter von Epp, a regular officer who would rise to a position of some power in the Nazi Party. Serving under von Epp was another veteran of World War I who would play an even more significant part in Hitler’s rise to power, Captain Ernst Röhm.

The battle for Munich, which lasted until 3 May, claimed some six hundred lives, over half of them civilian, and Eglhofer was murdered by the Freikorps. Sixty-five Spartacists were sentenced to hard labour and over two thousand were imprisoned. The Spartacist revolution had been put down but had left Chancellor Ebert’s hands caked with blood. In Berlin, the Spartacist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were both murdered while being held by the Freikorps and their bodies dumped into a river.

Spartacists are escorted into captivity in 1919. Many former soldiers, veterans of World War I, were among the recruits to the extreme right- and left-wing groups which clashed in pitched battles in the streets of post-war Germany. In Munich in March 1920, right-wing monarchists and Freikorps units briefly seized power in the so-called Kapp putsch. Hitler drew many lessons from this period of turmoil.

In deeply conservative Bavaria the traumatic events between November 1918 and May 1919 provided a shot in the arm for the radical Right. They not only confirmed the Right’s deep fear of the Bolshevism which had so recently been installed in Russia and was still fighting a bitter civil war against ‘White’ enemies of its own, but it also legitimized the use of extreme counter-revolutionary violence against the Bolshevik threat. Later, this provided Adolf Hitler with one of the principal planks in his political platform.

KAPP PUTSCH

In 1919 there were an estimated two hundred and fifty thousand men in Germany’s Freikorps, bands of armed veterans of World War I. In March 1920, under the troop reductions required by the Treaty of Versailles, orders were issued for the disbandment of Freikorps units, one of which was the Marinebrigade Erhardt. The President of the Weimar Republic turned down an appeal from General von Luttwitz, commander of the Berlin Reichswehr, to resist the programme of troop reductions. Luttwitz then ordered the Marinebrigade to march on Berlin and occupy it under the nominal leadership of an East Prussian civil servant and extreme nationalist, Wolfgang Kapp. When the Reichswehr refused to intervene, the Weimar government was forced to flee to Dresden and then Stuttgart, where it issued a call to Germany’s workers to resist the putsch with a general strike. The strike paralysed Germany, the putsch collapsed when other Freikorps leaders declined to support it, and Kapp and Luttwitz fled to Sweden.

LEARNING THE ROPES

What was Hitler doing during these dramatic events? His duties at the prisoner-of-war camp, which had been cleared of its inmates by the beginning of February, had come to an end, and his military record shows that on 12 February he was assigned to a unit to await demobilization. Extremely keen to remain in the Army, he managed to do so until March 1920, by which time he had discovered the oratorical gifts which were to launch his political career. In Mein Kampf, however, he devotes only a few pages to the days of Munich’s Red Republic, which were soon to offer so many lessons for the nascent Nazi Party. It seems that Hitler had good reason to be reticent about his weeks in Munich during the Bavarian Soviet’s seizure of power and its brutal suppression.

On 20 February 1919, Hitler’s demobilization company was assigned to guard duty at Munich’s Hauptbahnhof. The soldiers also earned a little extra cash by testing gas masks. Hitler, however, avoided his imminent demobilization. A routine order issued at the beginning of April identifies him as his company’s representative (Vertrauensmann), and it is likely that he had held this post from February. The precise functions of the company representative were determined by the propaganda department of Bavaria’s Socialist government and included providing ‘educational material’ to the troops. It would seem that Adolf Hitler’s first hands-on involvement in politics was as a low-level stooge of the men he would later stigmatize as the ‘November criminals’. Small wonder that this was a career move over which he was subsequently eager to draw a veil.

On 14 April, the day after the declaration of the Red Republic, the Munich Soldiers’ Councils sanctioned a round of elections of barracks representatives to ensure that the Army toed the party line. Hitler was elected as the deputy battalion representative and soon afterwards became the battalion representative. During the turbulent days of the Red Republic, the Army stood squarely behind the Spartacists, and it is inconceivable that Hitler could have carried out his duties as a representative without falling into line. However, whether he was acting sincerely or merely ensuring that he retained his relatively cosy billet in the Army is a question which cannot be answered definitively. Although his subsequent career shows that Hitler was an opportunist par excellence, his opportunism in Munich in the spring of 1919 was not an episode to which he could easily apply a favourable gloss. He made no attempt to join the Freikorps, and in all probability marched in mass demonstrations wearing the red armband of the Marxists.

More significant was the fact that, only days after the fall of the Red Republic, Hitler was appointed to serve on a committee which was charged with investigating whether any of his battalion had been active Spartacist supporters. The appointment ensured the deferral of Hitler’s discharge and, crucially, brought him into contact for the first time with counter-revolutionary politics within the army.

The end of the Red Republic effectively brought Munich under military rule, and the units which had been involved in putting down the uprising were organized into Gruppenkommando No. Four (Gruko). The Gruko moved swiftly to control the Education and Propaganda Department (Nachrichtenabteilung, Abt. Ib/P) which had been set up after the suppression of the Red Republic to instil in the troops the appropriate nationalist and anti-Bolshevist attitudes. Surveillance and propaganda were the orders of the day, and reliable speakers were recruited from the ranks to get the message across. This task would keep them in the Army for some time; it was the answer to Adolf Hitler’s prayers.

A series of courses in anti-Bolshevism was initiated for the soldiers. The man in charge was Captain Karl Mayr, head of the Education and Propaganda Department and the first of Adolf Hitler’s political patrons. Mayr was a man of influence beyond that merited by his rank. He was allocated considerable funds to establish a team of agents (effectively informants), devise a programme of education whereby officers and men would receive suitable indoctrination, and provide finance for nationalist and anti-Bolshevik political parties, organizations and publications.

Mayr first encountered Hitler in May 1919, in the aftermath of the battle of Munich, when Hitler was serving on the committee investigating the Communist affiliations of his comrades. Perhaps Mayr already knew of Hitler’s previous incarnation as a small cog in the Red Republic’s propaganda machine, but he seemed an ideal candidate for Mayr’s purposes, a tabula rasa on which the messages of the Education and Propaganda Department could be transmitted. Years later Mayr wrote of Hitler, ‘He was like a tired stray dog looking for a master … ready to throw in his lot with anyone who would show him kindness … He was totally unconcerned about the German people and their destinies.’

Early in June 1919, Hitler was taken on as a Verbindungsmann (a V-man or police spy). Within days he was attending his first anti-Bolshevik instruction course at Munich University, listening to lectures on German history, the theory and practice of Socialism, economics and the impact of the Treaty of Versailles, and the linkage between domestic and foreign policy. He soaked it up like a sponge. One lecturer who made an immediate impression on him was Gottfried Feder, a Pan-German nationalist, self-styled economics expert and critic of ‘rapacious capital’, which he associated with the Jews and contrasted with ‘productive capital’. Hitler, who already had an ear for a striking turn of phrase, intuitively grasped that Feder’s lecture on breaking ‘interest slavery’ had enormous propaganda potential. Feder would become an important figure in the early days of the Nazi Party.

Mayr was impressed by Hitler and selected him as one of twenty-six instructors sent to attend a five-day course at Lechfeld, near Augsburg. The course was a response to complaints that many returned prisoners of war now awaiting discharge had been infected with Socialist ideas. It was the task of the instructors to wean them away from Bolshevism and re-introduce them to the ‘correct’ nationalist modes of thought. Hitler threw himself into the work. Faced with a crowd of cynical soldiers, he discovered that he could engage the attention of these listless men and sway them with his arguments. These were not the monologues to which he had subjected his friend Kubizek, the endlessly patient audience of one. Now his words had a bigger audience, and a measurable effect. He found a voice as he lectured his charges on the history of the Red Republic, the causes of World War I, and the political lessons to be learned from its aftermath. Later he was able to boast of his success: ‘In the course of my lectures I led many hundreds, indeed thousands of comrades back to their people and fatherland. I “nationalised” the troops …’

Reports on the impact of his lectures at Lechfeld were uniformly enthusiastic. They characterized Hitler as a man born to be a public speaker and praised his ‘fanaticism’ and populist style. They also indicate that, now clearly heavily influenced by Gottfried Feder, at Lechfeld Hitler had ridden the anti-Semitic tide which prevailed at the time. Indeed, the commanding officer at Lechfeld, Oberleutnant Bendt, sought to restrain him in order to prevent charges of anti-Semitic agitation being levelled against the work being undertaken at the camp. Bendt’s intervention had been prompted by Hitler’s first public reference to the Jews during a lecture on capitalism.

Mayr was not so squeamish and was happy to refer queries on the ‘Jewish Question’ to Hitler, whom he evidently considered an authority on the subject. A response to a query from one Adolf Gremlich, on the Social Democratic government’s position on the Jewish Question, provides us with the first written evidence of Hitler’s developing attitude towards the Jews. He wrote that anti-Semitism should be determined by facts and not emotion. He considered that the application of ‘reason’ would lead to the conclusion that the Jews should be subjected to a systematic removal of their rights before they were removed themselves.

THE GERMAN WORKERS’ PARTY

Adolf Hitler was about to enter the political arena. The setting was Munich’s Sterneckerbräu, a beer cellar which was later to become a Nazi shrine. On the evening of 12 September 1919, still working as a V-Man, Hitler attended a meeting of the German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or DAP), one of over fifty small groupings flourishing in Munich’s murky political undergrowth and covering the political spectrum from the extreme Left to the extreme Right. The Army kept all of them under close surveillance.

The DAP had been founded in January 1919 by the economics theoretician Gottfried Feder, already familiar to Hitler from his anti-Bolshevik course at Munich University; Anton Drexler, member of a Munich brewing dynasty and a völkisch agitator; and the journalist Karl Harrer. Feder, Drexler and Harrer were members of the Thule Society, a German occult group whose pseudo-scientific beliefs coalesced around the notion of the Volk, the repository of mystical nationalism and romantic racism and, in their eyes, a bulwark against the capitalist and consumerist excesses of the modern world. Into this seedy den of racist crackpots and fantasists stepped Adolf Hitler.

Due to speak that night was Dietrich Eckart, another Thule Society man, founding member of the DAP, and an anti-Semitic ideologue. He had developed a theory of the ‘genius higher human’ based on the writings of Jorg Lanz von Liebenfels, the publisher of the racist magazine Ostara, which Hitler read during his days in Vienna. However, Eckart was ill and cried off, to be replaced by Feder who treated the audience to a now familiar theme: interest slavery.

Hitler had heard it all before and spent some time observing the assembled company. They were an unpromising bunch, all forty-one of them, but it was in the smallness and shabbiness of the DAP that Hitler saw his chance. According to his own account, he was already thinking of founding his own political party but here was one already formed, albeit with only a handful of disorganized and down-at-heel adherents, which might nevertheless serve his purposes as a ready-made vehicle which would enable him to flex his nascent powers of oratory.

After Feder’s address, comments were invited from the floor. A Professor Baumann, an advocate of Bavarian separatism, launched a fierce attack on Feder. This drew Hitler to his feet to deliver a stinging rebuke. Discomfited, the professor fled the tavern in disarray, prompting an impressed Anton Drexler to thrust a copy of his own pamphlet, My Political Awakening, into Hitler’s hands.

Drexler was reported to have said of Hitler, ‘Goodness, he’s got a gob on him. We could use a man like him,’ and invited him to another meeting.

Once again, Hitler’s account of the aftermath of this second meeting has to be treated with caution. The details were subsequently tweaked to fit the ‘Hitler myth’. He claimed that within a week of attending he had received a postcard which accepted him as a member and invited him to a committee meeting to further discuss the matter. In spite of his misgivings, he went along – he had at least been impressed by Drexler’s pamphlet. The new venue, a seedy beer cellar in the Herrenstrasse, was singularly unimpressive, as were the four members of the DAP who were present. After a few days of indecision – a trait which Hitler displayed until the end of his days – he decided to throw in his lot with the DAP, an organization which, with a combination of false modesty and shrewd insight, he estimated was small enough to offer an ‘opportunity for real personal activity’. In other words, he had decided to swap the Army for the DAP. Unlike the former, the DAP was small enough to provide the vehicle for Hitler’s ambitions.

An early example of the Hitler myth. This membership card was exhibited during the Nazi era, claiming that Hitler was the fifth member of the German Workers’ Party (DAP). In reality he was the fifty-fifth, and his membership number was later doctored to 555 so that the party would appear to have more members. Various versions of Hitler’s DAP card have surfaced since, featuring numbers as diverse as 5, 555, and 7.

Nevertheless, Hitler remained in the Army until 31 March 1920, when he was finally discharged, all the while drawing his army pay and with time available to devote to the DAP. Unlike other members of the DAP, who had regular jobs to go to, Hitler could now devote all his energies to his new-found career as a creator and disseminator of propaganda. Without the intervention of Captain Mayr, Hitler would in all probability have remained a face lost in the crowd, the archetypal ‘little man’ nursing unrealized fantasies of revenge on the world which ignored him. Hitler had not found politics; politics had found him, in the Munich barracks when he denounced his former comrades in the Red Republic and was talent-spotted by Mayr as a public speaker with a mesmerizing ability to connect with the gut instincts and basest prejudices of his audience. Karl Mayr had released Hitler’s demon, not yet fully formed but, in hindsight, now recognizable. Indeed, Mayr had ordered Hitler to join the DAP while the latter was still in the Army, an infringement of the ban on soldiers participating in political activity, and had provided him with supplementary funds. Mayr’s was an achievement of a baleful kind for which he, along with millions of others, would one day pay the ultimate price. His own political career followed a paradoxical trajectory from the far Right to the Left. He later became a Social Democrat, and when the Nazis came to power in 1933, he fled to France. However, after the outbreak of World War II, he fell into German hands and died in Buchenwald, the concentration camp near Weimar, in February 1945, two months before his protégé met his end amid the ruins of the Third Reich.

NATIONAL SOCIALISM

Initially, Hitler had nothing but contempt for the German Workers’ Party. The movement, if such it could be called, lacked headquarters, headed notepaper, finance, inspiring leaders and, above all, membership. Drexler and Harrer, its leading lights, were both dull platform speakers with little or no talent for organization. Then and later, this last ability was a very long way from being Hitler’s strongest suit but, in comparison with the DAP’s founders, he was at this stage in his career an organizational dynamo.

Drexler and Harrer seemed quite content for the DAP to remain little more than a political discussion club. Hitler thought differently. He harried the leadership into placing newspaper advertisements in the Münchener Beobachter for a meeting on 16 October 1919 at the Hofbräukeller, a large drinking establishment east of Munich’s city centre. Hitler was not the main speaker, but his speech, lasting some thirty minutes, brought the audience of one hundred and eleven people to its feet and raised three hundred marks for Party funds. Neither Drexler nor Harrer had served in the war, but Hitler, the Western Front veteran, had shrewdly enlivened the atmosphere by persuading some of his old army comrades to attend the meeting.

Buoyed by this initial success, Hitler insisted on bigger and more frequent meetings. Within a few weeks the audience was regularly reaching four hundred. At this point, according to Mein Kampf, Hitler insisted that the DAP stage a mass meeting, a demand which led to Karl Harrer’s resignation. Once again, Hitler got his own way, and the meeting was set for 24 February 1920. The venue was the Festsaal of the Hofbräuhaus in the centre of Munich, which was often used for large political meetings.

When it was not being used for political meetings, the big hall was packed with beefy male patrons, many of them wearing lederhosen, drinking their fill from long tables stacked with stone beer mugs. Dirndl-clad waitresses bustled back and forth bearing foaming tankards of ale to their bellowing customers. The Festsaal provided Hitler with an ideal arena in which to stage political theatre, the designs for which had been forming in the back of his mind since he watched the Socialist ‘human dragon’ winding through Vienna in the days before World War I. The atmosphere was not notably different during political meetings, and the beer flowed just as freely. There were frequent interruptions from the floor, and brawling regularly erupted between rival claques. This was politics in the raw, and meat and drink to Adolf Hitler. He was not in the least worried about disruption – he had been present at a mass meeting on 7 January 1920, attended by some seven thousand people, which had descended into a giant brawl. He was more concerned that on 24 February only a handful would turn up.

His concerns proved groundless. He had prepared the ground carefully. Dramatic red posters and leaflets advertising the meeting had been distributed. The party’s twenty-five-point programme, devised by Hitler and Drexler in the preceding weeks, was also printed and readied for distribution at the meeting. Significantly, however, there was no mention of Hitler in the advance publicity. On the night of 24 February, some two thousand people turned up, 20 per cent of them Socialist opponents spoiling for a scrap, to hear Dr Johannes Dingfelder, a well-known figure in Munich’s völkisch circles, deliver the main speech. It was, considering the occasion, unexceptionable. Dingfelder made no mention of the Jews and preferred to place the blame for Germany’s plight on the decline of religious faith and the rise of materialism. His answer? ‘Order, work and dutiful sacrifice for the salvation of the Fatherland.’

The mood changed when Hitler stepped forward to address the hall. He spoke in short, punchy sentences, robustly phrased, with which his audience readily identified – they spoke like this every day of their lives, although with infinitely less fluency. Hitler laid into the November criminals and men like Isidor Bach, one of Munich’s prominent Jewish capitalists, whom he attacked in tones both homely and deeply sinister: ‘When it is necessary to take a bowl of eggs away from a little hamster, the government shows an astonishing energy. But it will not use it if the hamster’s name is Isidor Bach.’

Explosions of frantic cheering greeted every slighting remark about Jews, and when Hitler turned his guns on war profiteers there were cries of ‘Flog them! Hang them!’ When he began to spell out the Party’s twenty-five-point programme, applause greeted every one of them. The first point demanded the union of all Germans into a Greater Germany. Many Germans were now citizens of Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. To bring them back into Germany could only be achieved by force, and this, in all probability, would mean war. Thirteen of the points were aimed against the Jews, including the assertion that ‘No Jew can be a citizen’. Jews were not to be allowed to hold public office or to publish newspapers. Those who had come to Germany after 1918 would be expelled.

There was spirited heckling from the Socialists in the audience, and the meeting constantly threatened to erupt into fisticuffs, but Hitler stuck to the last. At the climax of his speech he rebuked the government for providing food relief for Munich’s Jewish community, a sally which produced a storm of catcalls. Many of the audience were prompted to leap on to tables and chairs and hurl insults at each other as Hitler moved towards the end of his speech with words which would become familiar over the years: ‘Our motto is only struggle. We will go our way unshakeably to our goal.’

Hitler’s words closing the meeting were drowned out by the uproar in the hall. Socialists and Communists spilled out into the streets bawling the International, raising three cheers for the Red Republic and hurling insults at the German war leaders Hindenburg and Ludendorff and at German nationalists. Hitler later wrote, mendaciously, of a ‘hall full of people united by a new conviction, a new faith, a new will’. Nevertheless, the meeting had created controversy and had thus served its purpose very well. The fact that henceforth Nazi Party meetings were most decidedly not peaceful was a signal advantage which vividly set the DAP apart from its dull, bourgeois völkisch rivals. The opponents who packed DAP meetings before they began were themselves part of the spectacle. To deal with disruption, a ‘hall protection’ (Saalschutz) squad was formed – the seed from which the SA (Sturmabteilung) grew.

Dynamic design was also a vital ingredient in a mix which emphasized organisation, advance publicity, striking posters, and banners. The last was designed personally by Hitler and featured a black swastika (Hakenkreuz)6 on a white circle, framed by a red square. The makeover was completed by a new name: the DAP became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) – the Nazi Party.

In Munich at least, the Nazis were now on the map, and Adolf Hitler had put them there. Only Hitler, a man who seemingly had sprung from nowhere, appeared able to generate this excitement. Word raced around Munich that anyone attending a meeting addressed by Hitler was guaranteed a lively time.

One young man who saw Hitler speaking early in 1920, and was captivated by him, was Hans Frank, a World War I veteran and an early member of the NSDAP who, in World War II, became governor-general of the German-occupied territories in Poland. Awaiting execution for war crimes at Nuremberg in 1946, he recalled the first time he saw Hitler:

I was strongly impressed straight away. It was totally different from what was otherwise to be heard in meetings. His method was completely clear and simple. He took the overwhelmingly dominant topic of the day, the Versailles Diktat, and he posed all these questions: What now, German people? What’s the true situation? What alone is now possible? He spoke for over two and a half hours, often interrupted by frenetic torrents of applause – and one could have listened to him for much longer. Everything came from the heart, and he struck a chord with all of us …

How did Hitler do it? The building blocks of his speeches were, in the main, commonplaces peddled by all the parties of Munich’s nationalist Right: Germany laid low by the Allies, stabbed in the back, crippled by ruinous reparations and betrayed at home by corrupt politicians; the sinister figure of the Jew lurking behind all Germany’s ills, and the expulsion of all Jews from the country; the invocation of social harmony through national unity and the restoration of national greatness; the safeguarding of the archetypal ‘little man’ from the depredations of international financiers. Hitler’s list of enemies and his prescriptions for the future were, in themselves, unexceptional in the climate of the time. Where he differed was in the methods by which he ensured that his message got across, and the originality of his technique as an orator.

He spoke from rough notes, and at length, for two hours or more. In the Festsaal he cleverly addressed the audience from a beer table positioned on one of the side of the hall, thus placing himself in the middle of the crowd, the easier to gauge and orchestrate its mood. He quickly learned how to deal with shouted interruptions, foot-stamping, mocking laughter or even stony silence. He learned how to grab the attention of the audience, to read its collective mind – and individual minds – and to strike to the quick the listeners hanging on his every word.

Hitler’s formula was simple and cynical: ‘The receptive powers of the masses are very restricted and their understanding is feeble. On the other hand, they quickly forget. All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then expressed in a few simple phrases. Only by constantly repeating will you finally succeed in imprinting an idea on to the memory of the crowd … When you lie, tell big lies. This is what the Jews do. The big, cheeky lie always leaves traces behind it.’

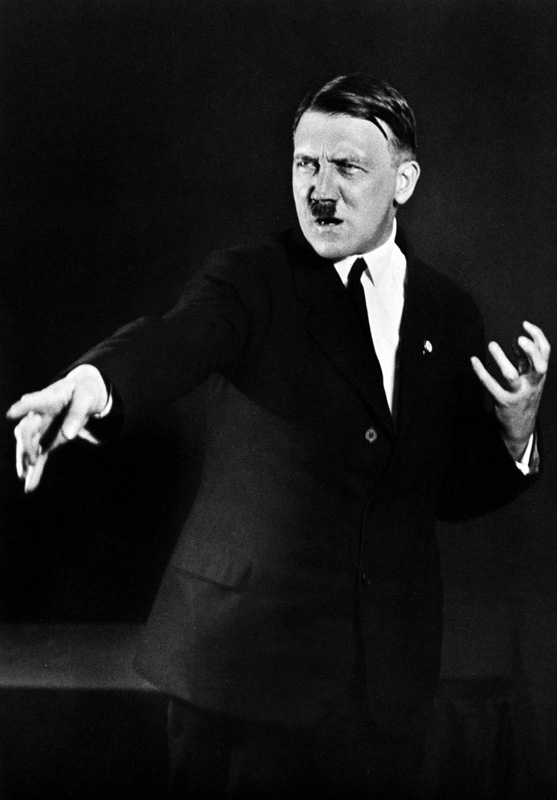

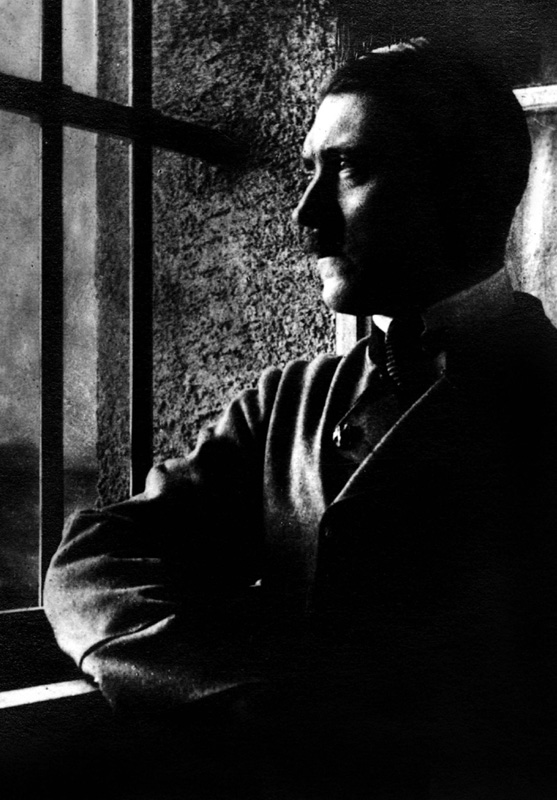

An actor prepares. In the 1920s, Hitler honed his speaking platform histrionics with obsessive attention to detail. His personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann would capture each gesture and posture before Hitler studied the results to select the precise choreography required to deliver the maximum impact.

Hitler’s choice of words matched his method. His oratorical vocabulary was simple, direct and violent. It featured heavily what would now be called buzz words – ‘smash’, ‘hatred’, ‘evil’, ‘power’ – which pressed all the right buttons with his audience. It is also as well to note the topics which, at this stage in his career, he did not mention or to which he referred only infrequently. In only one speech did he call for the establishment of a dictatorship in Germany, but he did not single himself out for this role. Nor did he introduce what was later to become a crucial element in his philosophy, the notion of Lebensraum (living space) in Eastern Europe, which would be colonized by German settlers after the expulsion and elimination of their Slavic populations. For the moment, Britain and France remained the principal targets of his ire and, in August 1920, he admitted that he was no expert on Russia. Nevertheless, he was fast catching up, influenced by Alfred Rosenberg. An early recruit to the Party, Rosenberg was of ethnic German descent but had been born in Russia, and he had seen the Russian Revolution at first hand.

Crowd control was also an essential element in Hitler’s method. The ‘hall protection squad’ was the first answer, burly ex-servicemen posted around the hall to silence troublesome hecklers. These roughnecks were later organized into strong-arm squads under the euphemistic name of the Gymnastic and Sports Division. In August 1921 the formation was strengthened by the addition of former members of the naval brigade led by Captain Hermann Ehrhardt, a seasoned campaigner in paramilitary activity and one of the leaders of the Kapp Putsch. In September 1921, the thugs from the Gymnastic and Sports Division played a prominent part in disrupting a meeting of the separatist Bayerbund, addressed by its leader Otto Ballerstedt. Ballerstedt brought charges against Hitler, and in January 1922 he was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, with two months suspended against future good behaviour. Hitler served his month-long imprisonment in Munich’s Stadelheim prison between 24 June and 27 July 1922. After his release, he remained unrepentant. Savage clashes with opponents were the lifeblood of the Nazi Party and fed its hungry publicity machine.

By the summer of 1922, the ad hoc squads had been reorganized into the Sturmabteilung (stormtroops), a formation whose name was swiftly abbreviated to the SA. They were supplied with brown uniforms, jackboots and swastika armbands. The Brownshirts, as they became known, quickly acquired an ugly reputation. Not content with merely maintaining order at Party meetings, they moved on to breaking up those of their opponents. Nevertheless, they represented only one small element in the bear-pit of Munich politics, in which they were, for the moment, dwarfed by other private armies.

In August 1922, the SA numbered some eight hundred men. They made their first appearance as a paramilitary organization at a huge nationalist rally in Munich for the United Patriotic Associations of Bavaria, whose slogan proclaimed, with regionalist fervour, ‘For Germany – against Berlin’. But, however menacing they might have seemed, the SA was dwarfed by the thirty thousand armed men of the Bund Bayern und Reich, a coalition of a number of right-wing factions which combined strong monarchist and Christian principles with anti-Semitism and hatred of Bolshevism. The Bund’s watchword had a familiar ring: ‘First the Homeland, then the World!’

The United Patriotic Associations of Bavaria soon collapsed in a welter of factional fighting. Hitler and the SA endured.

The SA made its name in mid-October 1922 when it followed Hitler to Coburg, in Upper Franconia, to participate in the so-called German Day (Deutscher Tag). This was new territory for the Nazis, whose power base remained in Munich. Hitler had been asked to attend with a small delegation but, with his usual flair for a propaganda coup, arrived accompanied by his eight hundred stormtroopers. The police had issued orders banning a march, which Hitler pointedly ignored. The SA marched from the railway station into the town, banners unfurled and swastikas held high. Along the route, they clashed with workers and supporters of the Socialists, who lined the streets abusing them. The SA responded with clubs and rubber truncheons, and a pitched battle ensued. One of Hitler’s men was Kurt Ludecke, a playboy ‘man of the world’ and recent recruit to the Sturmabteilung, who was at Hitler’s side on the march into Coburg:

The gates were opened against the protests of the now thoroughly alarmed police, and we faced the menacing thousands. With no music but only drums beating, we marched in the direction of the Schuetzenhalle. We who were in the forefront with Hitler were exposed to the very real danger for cobblestones were fairly raining upon us. Sometimes, a man’s muscles do his thinking. I sprang from the ranks towards a fellow who was lunging at me with his club uplifted. From behind me, my good Ludwig followed. But at the same moment our entire column had turned on our assailants.

The police initially held back, but now they pitched into the fray on the side of the SA. Ludecke recalled, ‘But soon, probably because they shared our dislike of the street rabble, most of them took our side, and before long we were masters of the field.’After a vicious battle lasting some ten minutes, the SA claimed the streets of Coburg and won another propaganda victory for Hitler. The NSDAP had left its mark; Coburg became a Nazi ‘battle honour’, and a special medal was struck for those who had taken part in the affray.

THE LEADER

Long before the SA began to crack heads in Coburg, Hitler was heading on a collision course with the leadership of the NSDAP. He was fast becoming central to the Party’s success but his increasing eminence was not universally popular. Several of the Party’s committee, including Gottfried Feder, were dismayed by what they considered to be his crude propaganda methods. The personal traits which were to characterize Hitler’s later political career were becoming evident to his colleagues. He was tetchily sensitive to any criticism, by turns impatient, irrational and hesitant, sometimes endlessly delaying decisions, at others charging into them precipitately. He was also violently opposed to plans hatched by Drexler to merge the NSDAP with another far-right party, the German Socialist Party (DSP).

Hitler’s truculent, unpredictable behaviour indicates that in 1921 he had not developed a rational, long-term plan to take control of the NSDAP. He had not anticipated a power struggle but nevertheless found himself in one, and prevailed by using all-or-nothing tactics – a desperate gamble which succeeded in unnerving his indecisive enemies, who failed to present a united front. It was a pattern he would repeat over the years and which, ultimately, proved the ruin of the Third Reich.

When the crisis broke, Hitler was in Berlin, raising funds. The malcontents in the NSDAP had been casting around for a counterbalance to their troublesome pre-eminence, someone to clip his wings, and lit upon Dr Otto Dickel. Dickel headed another recently formed völkisch organization, the Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft, who had recently scored a publishing success with The Resurrection of the Western World. Dickel’s windy völkisch philosophizing was not to Hitler’s taste, but his violent anti-Semitism and plans to build a classless community through national renewal dovetailed with Hitler’s ideas. And, like Hitler, Dickel was a fiery orator. While Hitler was in Berlin, Dickel gave a well-received speech in one of Hitler’s stamping grounds, the Festsaal of the Hofbräuhaus. More speeches were planned. Dickel seemed to be the answer to the prayers of those who were unhappy with the prima donna Hitler. Above all, he was controllable.

Hitler returned from Berlin to discover that talks about a new merger, this time with Dickel’s party, were imminent. Like a spoilt child, he responded with a tantrum followed by moody sulking. And, like a child, he had failed to get his own way. On 11 July, he resigned from the Party. Now, it seemed, Hitler was back where he began. He would have to establish his own party. Then Drexler blinked. He realized, belatedly, that the loss of Hitler might prove catastrophic. Perhaps, after all, Dickel was not the man to replace him. Within days Hitler was asked to rejoin the Party. Hitler seized his chance. He would rejoin, but only on his own terms: he would assume the post of party chairman with dictatorial power;7 the party headquarters must be in Munich; the twenty-five-point programme was inviolate; and there would be no more attempts to merge with other parties. Within twenty-four hours the Party committee had caved in and acceded to Hitler’s demands. On 26 July, six days after a triumphant rabble-rousing appearance before a packed house at the Circus Krone, he was welcomed back as Party member number 3680. Game set and match to Adolf Hitler.

There was another outburst of snapping and snarling before the dust settled, the last death twitch of Hitler’s opponents in the NSDAP. Placards denouncing him were prepared and an anonymous pamphlet appeared attacking him as the agent of sinister forces. He brushed his opponents aside and, in an extraordinary meeting at the Festsaal, so recently the scene of Dickel’s transient triumph, members voted five hundred and fifty-three to one to accept the new dictatorial powers sought by their leader. A constitution, hurriedly drafted by Hitler, confirmed his supremacy not once but three times. The Nazi Party was about to undergo a transformation. It was to become a ‘Führer party’, in which the Führer’s word was law, subject to rubber stamp approval by the membership.

THE COURTIERS

In less than two years Adolf Hitler had travelled from being an anonymous police spy to assuming the leadership of the NSDAP. During these early years, he began to gather round him a circle of intimates, many of whom would, from 1933, occupy positions of untrammelled power in Germany, and later in Occupied Europe.

An important figure in these years was Captain Ernst Röhm, a scarred veteran of the ‘front generation’, who rapidly replaced Karl Mayr as Hitler’s link with the German Army, the Reichswehr. Early in 1920, at a time when Hitler himself was still in the Army, Mayr had taken him to meetings of the Iron Fist club, an association of radical nationalist serving officers which had been formed by Röhm in defiance of the rule that the Reichswehr should remain apolitical. In all probability, Hitler had already been introduced to Röhm by Mayr in the autumn of 1919. Röhm had joined the DAP in October 1919, shortly after the meeting at which Hitler had first found his political voice.

In the winter of 1919, however, Röhm was more interested in the Citizens’ Defence Force (Einwohnerwehr) than in the tiny DAP. This heavily armed paramilitary organization, numbering some four hundred thousand men, had been formed after the crushing of the Red Republic and presented the traditional face of Bavarian reaction. Röhm, nevertheless, kept a finger in the pie of any number of völkisch movements in Bavaria and, from 1921, became a significant figure in the NSDAP and the development of the Sturmabteilung. By 1923, the SA was some fifteen thousand strong and, thanks to the ‘machine-gun king’ Röhm, was armed to the teeth. Röhm was a man with sensitive political antennae but, like his associate Hermann Ehrhardt, was nevertheless wedded to the application of exclusively paramilitary answers to political questions. For Hitler, however, the wholesale integration of the SA into the political framework of the NSDAP was a problem which was to become increasingly troublesome as the years went by. The resolution, when it came, was bloody. Ernst Röhm, who had always lived by the sword, was to die by the sword in 1934 in the Night of the Long Knives.

Another significant early figure in Hitler’s rise to prominence in the politics of Bavaria was Dietrich Eckart, an alcoholic who was to die in 1923. If the brutal, homosexual Röhm provided the brawn of the NSDAP, then Eckart was the brain. Twenty years older than Hitler, he was an unsuccessful poet and critic who had entered politics in December 1918 with the publication of a violently anti-semitic weekly magazine, In Plain German (Auf gut deutsch), whose regular contributors included Gottfried Feder and Alfred Rosenberg. Eckart had spoken at DAP meetings before Hitler had joined and later took the new recruit under his wing. He helped Hitler to widen his reading, gave him a little social polish and introduced him to significant financial backers. One of them was the Augsburg industrialist Dr Gottfried Grandel, who had funded In Plain German and also acted as guarantor for the funds that the NSDAP used to purchase the bankrupt newspaper the Völkischer Beobachter (People’s Observer) in December 1920. Its first publisher was Dietrich Eckart.

One of Hitler’s earliest and most slavish disciples was Rudolf Hess. Born in Egypt, the son of a successful wholesaler and exporter, Hess did not live in Germany until he was fourteen. He served in the List Regiment during World War I but had not met Hitler. After the war he joined the Freikorps, and while studying at Munich University came under the influence of the Thule Society and Professor Karl Haushofer, a former soldier. Haushofer’s geopolitical theories of race and expansionism would play a part in the concept of Lebensraum, one of the last major elements in Hitler’s Weltanschauung (world view). Hess joined the NSDAP on 1 July 1920, and after meeting Hitler, felt that he had been ‘overcome by a vision’.

Among the earliest members of the NSDAP, Hermann Göring had the highest public profile. A World War I air ace with twenty-two victories under his belt, the fleshily handsome, flamboyant Göring had commanded JG1, the legendary Richthofen squadron, during the closing months of the conflict. In 1920 he married a wealthy Swedish countess, settled in Munich, and in 1921 had joined the NSDAP, making his aristocratic connections and wife’s fortune available to the Party. In 1923 Göring was appointed head of the Sturmabteilung.

Undoubtedly one of the most unpleasant members of this unappealing bunch was Julius Streicher, a bald, burly bully and lecher, who thrashed his enemies with a rhino-hide whip. Another war hero – he was also awarded the Iron Cross (First Class) – Streicher was a virulent anti-Semite who, after the war, was one of the founding members of the German Socialist Party, or DSP (Deutschsozialistische Partei), whose basic philosophy differed little from Nazism. In 1923 Streicher established his own newspaper, Der Stürmer (The Attacker), which dripped with obscene caricatures of hook-nosed, bearded Jews ravishing innocent Aryan maidens and achieved the rare distinction of being banned in the Hitler Youth, and in all the departments of the Third Reich run by Hermann Göring. Vile though he was, Streicher proved an invaluable ally to Hitler in the development of the NSDAP in Protestant Franconia, in northern Bavaria, which was to provide the Nazi Party with a symbolic capital in the city of Nuremberg.

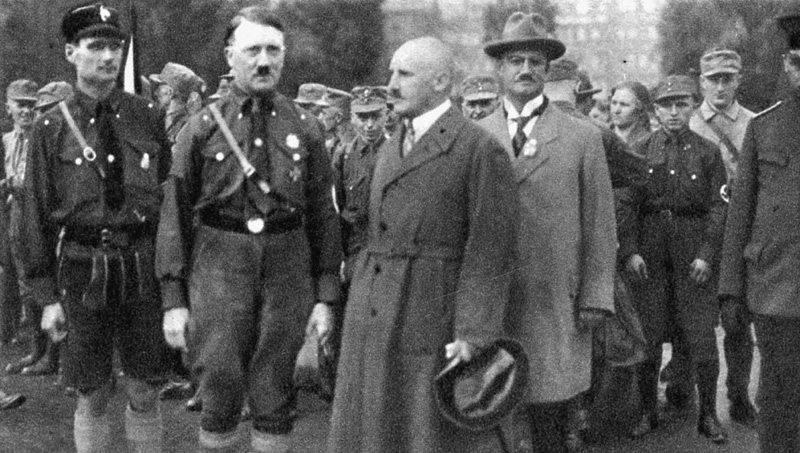

(Left to right) Alfred Rosenberg, Hitler and Friedrich Weber, head of the Bund Oberland, during a parade of the SA and other paramilitaries marking the laying of the war memorial foundation stone in Munich, 4 November 1923.

Although Hitler had now become a familiar player on Munich’s political scene, his personal habits had in many ways changed little since his time in pre-war Vienna. The most significant difference was that he now had an audience hanging on his every word as he lounged around in his favourite haunts, among which was the Café Heck in Galerienstrasse, a popular watering hole of Munich’s bourgeoisie, where Hitler would hold court for long hours. Among his inner circle were Max Erwin von Scheubner Richter, an engineer who had excellent contacts among Russian émigrés, Alfred Rosenberg and, from late 1922, Ernst ‘Putzi’ Hanfstaengl,8 a tall, cultured half-American and a graduate of Harvard, who became Hitler’s foreign press chief.

Hanfstaengl, who came from a family of art dealers, was fascinated by Hitler, this awkward little man in a shabby blue suit, who was a mixture of NCO and railway clerk but nevertheless possessed the gift of swaying the masses. Hanfstaengl’s fascination, however, was tempered by a snobbish attitude towards Hitler’s clumsiness in clever and sophisticated company – he was awkward with a knife and fork, sprinkled sugar into vintage wines, knew little about art, about which Putzi knew a great deal, and frequently resorted to blustering monologues or long periods of brooding silence to cover his ignorance. In a small group, or one-to-one, Hitler often appeared an unimpressive, even sometimes ludicrous, figure. The fastidious Hanfstaengl could nevertheless overlook these social shortcomings because he considered Hitler ‘a virtuoso on the keyboard of the human psyche’. Riding the irresistible emotional surge of a mass meeting, Hitler had no equal.

Just as Röhm ensured that Hitler enjoyed contacts at the highest level with representatives of the Reichswehr in Munich, so Hanfstaengl introduced him to the upper echelons of Munich society, whose dominant females vied with each other to present their newly found acquaintance with gifts of bulky dog whips and hefty donations to NSDAP funds. In this milieu Hitler cut a curious figure, prompting one Freikorps leader of the time, General Rossbach, to observe, with some accuracy, that he was ‘a man mistrustful towards himself and what he was capable of, and so full of inferiority complex towards all who were anything or were on their way to outflank him …. He was never a gentleman, even later in evening dress.’

There were many in Hitler’s inner circle who were also not gentlemen and who were happy to sit at his feet every Monday evening at the Café Neumaier. The company here was a world away from the decorous salons of upper-class Munich. Nazi philosophers like the anti-Semite Dietrich Eckart were joined by other more rough-hewn Party members: Christian Weber, a former bouncer and horse-dealer who, like Hitler, habitually affected a dog whip; Max Amann, Hitler’s sergeant in the List Regiment; and Ulrich Graef, a butcher and amateur wrestler who was Hitler’s personal bodyguard. At the end of the evening this band of cronies – the so-called ‘chauffeureska’ – would act as bodyguard to their leader, theatrically dressed in a black trilby and long black overcoat, and escort him back to his modest lodgings in Munich’s Thierschstrasse.

A NEW CRISIS

Between 1919 and 1923 Hitler’s audiences grew steadily in size. In 1932 he recalled, ‘I cast my eyes back to the time when with six other unknown men I founded [the Nazi Party], when I spoke before eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen, twenty, thirty, fifty persons. When I recall how after a year I had won sixty-four members of the movement, I must confess that that which has today been created, when a stream of millions is flowing into our movement, represents something unique in German history’.

By 1923, the stream of millions had not yet begun to flow. Hitler’s followers were still numbered in thousands, but the events of that year provided a pretext for him to launch a military putsch in Munich. It ended in disaster, but its dramatic failure thrust Hitler for the first time on to the national stage.

The French had precipitated a crisis at the beginning of the year. In January 1923, in order to force the German government to sustain reparations payments which it had insisted it could not meet, the French government sent troops to occupy the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland, and extract payment at source. The French needed the income from reparations to balance their own budget and pay their debts to the United States, and imagined that the seizure of the factories and mines of the Ruhr would both solve the problem and exact the revenge denied by the German surrender in 1918.

The Ruhr was paralyzed, and the effect on the entire German economy was disastrous. The German mark collapsed and hyperinflation set in. In December 1922 the exchange rate stood at eight thousand marks to the US dollar. Ten months later it had soared to four million, two hundred thousand marks to the dollar. Money became worthless and barter took over as the normal method of trading. Workers were paid daily and spent the money as soon as they received it, lest its value plummet further. The government needed to print more and more money; eventually it had three hundred paper mills and two thousand printing plants working twenty-four-hour shifts to meet the demand.

Gustav Stresemann, who had become Germany’s chancellor in August 1923, initially called for a campaign of passive resistance in the Ruhr. This did nothing to deter the French, but set an example of illegality which encouraged Communists in Saxony and Hamburg, separatists in the Rhineland, and former Freikorps men in Pomerania and Prussia, to threaten civil disobedience. In this situation most people were losers. In a matter of days a lifetime’s savings could become valueless.

‘Our misery will increase. The scoundrel will get by. The reason: because the state itself has become the biggest swindler and crook. A robber’s state!’

Thus declared Adolf Hitler, to whom those hit hardest by the crisis – the German workers and middle classes – offered a fertile recruiting ground. A plan began to form in his mind, based not on a German but on an Italian example. The Freikorps phenomenon had not been confined to Germany. After 1918 the world was awash with weapons and with rootless men inured to violence. There was no shortage of freebooting officers eager to lead them on death or glory missions. Italy, with little to show for its six hundred thousand war dead, was an arena in which such desperate men flourished.

After the war there was an economic crisis which the traditional Italian parties, religious and political, were wholly incapable of solving. The only leader to promise salvation was Benito Mussolini, a former Socialist and founder, in 1919, of the Fascist Party (Fascio di Combattimento), the so-called Blackshirts (Squadristi). Like the Freikorps, the Squadristi were used by the government as strike breakers and as a stick with which to beat Socialists. Mussolini was the archetypal Freikorps type, a man of action who advocated military-style solutions to the country’s difficulties. As with the Freikorps, the Fascist Party’s activists were drawn from ex-servicemen, among whom the most effective were former arditi (stormtroops). Mussolini promised to establish strong government and restore national pride. Communism was identified as the principal threat, while Fascism offered the prospect of dynamic action and leadership in contrast to the inertia of the established parliamentary parties.

Mussolini’s ‘March on Rome’ began on 27 October 1922. The Fascist leader was careful to be photographed striding out with his Blackshirts but did not walk all the way. He had made his aim clear in a speech delivered in Naples on 24 October: ‘Our programme is simple. We want to rule Italy.’ The Italian prime minister, Luigi Facta, fondly believed that Mussolini could be accommodated and, having been muzzled, given a role in government. But Mussolini now enjoyed the support not only of the Italian military, but also the business class, the political Right and King Victor Emmanuel III. Victor Emmanuel, assured by Mussolini that he would keep his throne, refused to sign an order declaring Rome to be in state of siege and, on 29 October, power was transferred to Mussolini, who became prime minister, within the framework of the Italian constitution.

The next day the new prime minister arrived in Rome, resplendent in a black shirt, black trousers and a black bowler hat. The March on Rome was never the heroic seizure of power later celebrated by Fascists. The Italian Army could have easily crushed the twenty thousand sodden, bedraggled marchers had it chosen to do so: the transition had been made possible by the surrender of public authorities in the face of Fascist intimidation. By the summer of 1924, Mussolini had become the dictator of Italy.

The March on Rome made a deep impression on the NSDAP. Mussolini was the kind of hero needed in Germany, striding to the rescue of the nation at the head of his own private army. At the beginning of November 1922, at a packed meeting at the Festsaal in the Hofbräuhaus, Hermann Esser, editor of the Völkischer Beobachter, declared, ‘Germany’s Mussolini is Adolf Hitler!’ Just as the March on Rome launched Mussolini as Il Duce, the leader of Italy, so Hitler’s followers were now to subscribe to the Führer cult which sprang up around their own leader.

In the Weimar Republic, tottering from one crisis to the next in a bullies’ playground of warring private armies, the cult of a strong leader guiding his followers and the nation to salvation – a long German tradition – exercised an inexorable grip on the imagination of parties of the nationalist Right. After Mussolini’s triumph, however bathetic, Hitler’s role in the NSDAP was cast in a different light. In December 1922 the Völkischer Beobachter suggested that he was a special kind of leader, that indeed, like Mussolini, he was the leader for whom Germany was waiting. Rank and file Nazis had long thought this, and Hitler had done little to discourage them. But he had also done little actively to foster a personality cult around himself. In 1922 he disingenuously told the Hamburg neo-conservative intellectual Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, ‘I am nothing but a drummer and a rallier.’

Now a gradual process of change began. By the beginning of May 1923, in a speech lambasting the parliamentary system, Hitler invoked the image of two of Germany’s greatest titans of the past, Frederick the Great and Bismarck. He affirmed that Germany could be saved only by a ‘dictatorship of the national will and national determination’. But the task of the nation was to ‘create the sword that this person will need when he is here. Our task is to give the dictator, when he comes, a people ready for him!’

MILITARY MANOEUVRES

The May meeting at which Hitler urged his audience to forge a sword for the future dictator of Germany came after six months of frantic political activity in Munich where, from December 1922, rumours were rife that a putsch was being planned by the NSDAP. When the French marched into the Ruhr in January 1923, Hitler turned his guns on the November criminals in a mass meeting at the Circus Krone. For him, the real enemy was within. It was a familiar roll call. Parliamentary democracy, Marxism, internationalism and the Jews had caused Germany to be held to ransom by the French. He expressly ordered Party members not to offer active resistance to the occupation.

At the end of the month the jittery Bavarian government declared a state of emergency in an attempt to prevent the NSDAP from holding its first ‘Reich Rally’. Röhm saved the day, persuading the German Army to come out in support of Hitler, who assured the local commander, General Otto Hermann von Lossow, that the rally would be peaceful. The police and the government president of Upper Bavaria, Gustav Ritter von Kahr, were also brought on board, and Hitler was allowed to address twelve mass meetings on the same evening. In addition, he attended the dedication of SA standards at Munich’s Marsfeld in the company of six thousand uniformed stormtroopers. It was a great propaganda triumph, which saw Hitler’s first use of the Fascist outstretched-arm salute, borrowed from the Italian Fascists who had themselves filched it from the Romans.

A month later Ernst Röhm, the man who in January had enabled Hitler to defy the Bavarian government, cut across his leader’s bows by establishing the Working Union of Patriotic Fighting Associations (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Vaterländischen Kampfverbände). The Union combined the SA with a number of private armies of the nationalist Right as a force potentially to be used not against the French but against the government in Berlin. Hitler was furious at losing direct control of the SA, but Röhm had seen to it that he was now in the political fast lane, charged with drafting a statement of the Working Union’s political aims and meeting, thanks again to Röhm’s string-pulling, the commander-in-chief of the Reichswehr, Colonel-General Hans von Seeckt. Hitler, however, failed to impress the Colonel-General. The disdainful Seeckt nevertheless did his job well; by the time he was dismissed for harbouring monarchist sympathies in 1926, he had laid the foundations for the rapid expansion of the Reichswehr in the 1930s.

At the end of February, Hitler was brought into contact with his wartime commander-in-chief, General Ludendorff, who had returned to Munich from exile in Sweden early in 1919 and thrown his hat into the seething ring of Munich’s politics. Ludendorff urged the use of paramilitary formations in a strike against the French. Hitler had already agreed to the military training of the SA by the Reichswehr in January, and the stormtroops handed over their weapons to the army in anticipation of a scrap with the French. Much of this manoeuvring was not to Hitler’s liking, but thanks to Röhm he had now been admitted to the political top table in Munich.

The price Hitler paid for these developments threatened to be a heavy one. He was losing control of the very elements he needed to force the pace of political developments in Bavaria. He was being elbowed out of the action by more powerful figures whose agendas differed from his own. At the beginning of May, he was forced into another confrontation with the government of Bavaria. On May Day, the Socialists were to march through Munich, a demonstration for which they had obtained police permission. In the feverish atmosphere of the time the nationalist Right, for whom 1 May marked the anniversary of the downfall of the hated Red Republic, saw this as an outright provocation. Violence was in the air; already, on 26 April, shots had been exchanged between armed Communists and members of the NSDAP in which several of the combatants had been wounded. The armies of both Right and Left were spoiling for a fight.

They were to be denied. First, the police withdrew permission for the Communists’ march, restricting them to a limited demonstration in the centre of Munich. Then the right-wing paramilitary groups’ demand that the Reichswehr return their weapons was denied. This time the jellied nerve of the state authorities had remained firm. The paramilitary groups were given a sop – permission to gather in a northern suburb of Munich near the barracks, but well away from the Communist demonstration. It was a low-key affair, attended by some two thousand men, about half of them from the NSDAP, and ringed by a cordon of police. There was some half-hearted drilling, with weapons supplied by the ‘machine-gun king’, but this was no substitute for the anticipated pitched battle with the forces of the Left.

At a meeting that night in the Circus Krone, Hitler tried to make the best of a bad job, railing against the Jews, whom he called a ‘racial tuberculosis’. The police observer reporting the meeting wrote of a ‘pogrom mood’. As the summer wore on, however, Hitler became acutely aware that the NSDAP, and more importantly the SA, could not be kept on the leash indefinitely. Moreover, he was being outflanked by the war hero Ludendorff, who since his return to Munich was rapidly becoming the focal figure in Germany’s ‘national struggle’. It was Ludendorff who, at the beginning of September, was the star attraction of the German Day held at Nuremberg and attended by a crowd of over a hundred thousand. Scheduled to coincide with the anniversary of the humbling of the French at Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), it was a gathering of the nationalist Right which enabled Hitler to recover much of the prestige he had lost after the May Day fiasco. He had a seat on the saluting base for the climactic paramilitary march past, alongside Ludendorff and Prince Ludwig Ferdinand of Bavaria, and was judged to have given by far the best speech.

Reward of a kind came three weeks later when Hitler was given the ‘political leadership’ of the German Combat League (Deutscher Kampfbund) which amalgamated the paramilitary groupings, including the NSDAP, under the military leadership of Lieutenant-Colonel Hermann Kriebel, who had formerly headed the Union of Patriotic Fighting Associations. Once again, this realignment of the forces of the Right in another umbrella organization had been engineered by Röhm, who also ensured that the Bund’s business manager was one of Hitler’s cronies, Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter. Again, this left Hitler in a no-man’s-land, stranded between the military professionals – Röhm and Ludendorff – and the political activists. Röhm considered Hitler one of the latter, a born rabble-rouser but not the man to plan and lead a coup. Hitler, on the other hand, was determined to subordinate the role of the paramilitaries to the building of a revolutionary mass movement through the NSDAP. There was no effective meeting of minds on this thorny problem, but one thing on which Hitler, Röhm and Scheubner-Richter did agree was that any attempt to mount a coup in Bavaria in the teeth of opposition from the police and the military was doomed to failure.

Stosstruppe Adolf Hitler (Adolf Hitler Assault Squad), which was Hitler’s original personal bodyguard. Formed in May 1923, the Stosstruppe was a group of roughnecks led by Julius Schreck. They wore distinctive death’s head badges, a link with the Imperial past which was later to be adopted by the SS. Schreck subsequently became the first Reichsführer SS (a post he never acknowledged) before becoming Hitler’s driver. He died of meningitis in May 1936 and was given a state funeral at which Hitler delivered the eulogy.

THE BEER-HALL PUTSCH

On 26 September 1923 the government in Berlin called off the strike in the Ruhr and pledged to resume reparations payments. This threatened to take the wind out of the sails of the Communists and the nationalist Right. The longer the crisis lasted, the greater became the possibility of civil war from which those on each side of the political divide anticipated they would emerge victorious.

The Communist threat in Hamburg, Saxony and the Ruhr was swiftly snuffed out by the Army. It was all over by the end of October. The threat from the Left had been eliminated at the first whiff of grapeshot. The menace from the Right sprang from Bavaria, where extreme nationalists were using the ‘Red threat’ as an excuse to march on Berlin. Bavaria’s immediate response to the ending of passive resistance was to proclaim a state of emergency which granted Gustav Ritter von Kahr, a monarchist of the old school, dictatorial powers as General State Commissar. One of his first acts was to ban a series of meetings to be held by the NSDAP. Kahr was to rule Bavaria at the head of a triumvirate whose other members were the state police chief, Colonel Hans Ritter von Seisser, and the local Reichswehr commander, General Otto Hermann von Lossow.

The triumvirate had its own agenda: envisaging a German version of Mussolini’s March on Rome, they were aiming at the installation of a nationalist dictatorship in Berlin with the support of the Reichswehr. Hitler, Ludendorff, and the Kampfbund were excluded from the plan. In the fevered atmosphere of the time, the triumvirate was queasily aware that it could be outmanoeuvred by Hitler – if he made his move first. Seisser travelled to Berlin to square Seeckt but was sent away with a flea in his ear. The commander of the Reichswehr flatly refused to move against the legally constituted government. Seeckt followed up by sacking Lossow, a move which was simply ignored by the triumvirate, who made the troops in the state swear an oath of loyalty to the Bavarian government. Seeckt issued a stern warning that any move by the triumvirate would be crushed by force.

Hitler was now coming under intense pressure to act. Scheubner-Richter warned him, ‘In order to keep the men together, one must finally undertake something. Otherwise the people will become Left radicals.’ By 7 November, when the Combat League leaders met, a plan had emerged. In the principal cities and towns of Bavaria, communications hubs and police stations were to be seized. Communists, Socialists and trades union leaders were to be arrested. The Combat League leaders agreed to Hitler’s demand that the strike should be launched the next day, 8 November, when all the prominent political figures in Munich would be gathered in the Burgerbräukeller to listen to a speech by Kahr denouncing Communism. Hitler had been forced to make a pre-emptive strike to launch his own Bavarian revolution before the triumvirate set its own plan in motion.

On the night of 8 November, three thousand people were packed into the Burgerbräukeller, one of the largest halls in Munich. It was a cavernous space with a high ceiling from which were suspended ornate chandeliers; a balcony ran down one side. The doors had been closed at 7.15 p.m. and a large crowd milled about outside in a light drizzle. Kahr had been speaking for about half an hour when Hitler began to push his way through the crowd accompanied by two stormtroopers brandishing pistols. He clambered on to a chair, drew a Browning pistol and fired a shot into the ceiling. When the tumult died down, he announced that the national revolution had begun and that the Burgerbräukeller was surrounded by six hundred armed men. He warned that if there was any trouble he would bring a machine gun into the gallery.

Hitler then invited the triumvirate to retire with him to an adjoining room. They had little choice in the matter. There, brandishing his pistol in a state of wild excitement, Hitler announced the formation of a new government with himself at its head, and promised ministerial posts to his captive audience if they agreed to cooperate. He warned them, in the tones of a ham actor, ‘I have four shots in my pistol. Three for my collaborators if they abandon me. The last is for myself.’Then, putting the Browning to his temple, he declared, ‘If I am not victorious, by tomorrow afternoon I shall be a dead man’.

Having laid his cards on the table, Hitler returned to the hall to reassure the restive crowd that his actions were not directed at the police or the Army, but ‘solely at the Berlin Jew government and the November criminals of 1918’. He outlined his proposals for the new governments in Berlin and Munich and added that Ludendorff was to be made army commander-in-chief, with dictatorial powers. The crowd roared its approval when he declared that he would inform the triumvirate that it had the full support of the audience.

Shortly afterwards, Hitler, accompanied by the triumvirate and Ludendorff, who had arrived wearing the full uniform of the Imperial Army, returned to the podium. After shaking hands with Hitler, they all made short speeches announcing their new roles and their willingness to co-operate. Spontaneously, the crowd burst into ‘Deutschland über Alles’. Ominously, Rudolf Hess then began to call names from a list of those present who were to be detained for interrogation and trial. The remainder of the crowd was asked to leave as sympathizers from across Munich began to arrive. Hitler, it seemed, had carried the day.

Outside the hall, however, as well as taking over three large beer halls in the centre of Munich, Röhm and the SA had occupied the War Ministry, but had failed to commandeer its switchboard. This oversight allowed Lossow to order loyalist troops into the city. The cadets at the infantry school came out in support of the putschists, and paramilitaries loyal to Hitler had occupied the offices of the influential Münchener Post newspaper. But that was the extent of their success. Moreover, Ludendorff had made a fatal blunder. Left in charge of the Burgerbräukeller while Hitler went off on a vain mission to secure the engineers’ barracks, he had allowed the triumvirate to leave, accepting their word as officers and gentlemen. They were now free to renege on the agreement they had made with Hitler at gunpoint.

In the centre of Munich high-spirited paramilitaries were parading with posters proclaiming Hitler as chancellor. But inside the Burgerbräukeller, amid the fug of cigarette smoke and piles of stale bread rolls, the moment of glory had passed.

Early the following morning a correspondent from The Times newspaper made his way to the Burgerbräukeller, where he found Hitler and Ludendorff in a small upstairs room. The quartermaster general and the corporal – the walrus and the carpenter – staring down the barrel of a gun. Hitler, the journalist wrote, was exhausted: ‘… this little man in an old waterproof coat with a revolver at his hip, unshaven and with disordered hair, and so hoarse he could barely speak’. Ludendorff, as well he might have, looked ‘anxious and preoccupied’.

The putschists were glumly considering a rapidly dwindling list of options. Hitler suggested driving to Berchtesgaden to enlist the support of Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria. Lieutenant-Colonel Kriebel urged a tactical withdrawal to Rosenheim, near the Austrian border, where an armed resistance could be mounted against the inevitable Reichswehr riposte. While they talked, the paramilitaries began to trickle away. Finally, Ludendorff came up with the idea of a demonstration march through the streets of Munich, a desperate gesture which just might pick up speed, like a snowball rolling downhill, to become an avalanche. Surely the presence of Ludendorff, the totemic nationalist hero, would prevent the police and troops waiting in the streets of Munich from opening fire.

Shortly after noon, a column of some two thousand men, many of them still armed, set off from the Burgerbräukeller into the centre of Munich. Their destination was the War Ministry. In the front rank, marching beneath the swastika and the flag of Imperial Germany, was Hitler, with Ludendorff and Scheubner-Richter on either side. Close by were the bull-necked Ulrich Graef, Gottfried Feder and Hermann Göring, resplendent in a full-length leather overcoat, his Pour le Mérite medal, the ‘Blue Max’,9 at his neck. They were followed by SA men from the paramilitary Bund Oberland, marching four abreast in front of a car bristling with weapons. Bringing up the rear was a raggle-taggle army of students and fellow-travellers, some marching smartly in step and wearing their uniforms and medals from World War I. Many of them could not fail to notice that the posters proclaiming the revolution had already been torn down. To curious members of the public the march seemed like a funeral procession. And so it was.

The column broke through the first police cordon but encountered a second and more formidable barrier as it approached Odeonsplatz. Someone, possibly a bystander, cried out ‘Heil Hitler’ and then shots rang out, the preliminary to a fierce fire-fight which lasted only some thirty seconds but left fourteen putschists and four policemen dead. One of the dead was Scheubner-Richter, who pulled Hitler down with him as he fell, dislocating his leader’s left shoulder. Hitler struggled to his feet and escaped in a car. Göring was shot in the leg and badly wounded. The lone figure of Ludendorff marched on through the carnage and the police cordon but no one followed. Behind him, the column broke and fled.