BATTLE FOR THE BALTIC

Any submarine sailing in the Baltic Sea theater of operations during World War Two faced demanding and hazardous conditions. The shallow waters were tough to navigate. Once submarines attack, they must dive at least 200 to 300 feet deep: There are few places of such depth in the Baltic.

Because Hitler’s strategy was to keep the Soviet fleet trapped in the Gulf of Finland, the German navy relied on an array of antisubmarine defenses.1 One tactic was to lace the Gulf of Finland’s coastline with mines and nets. Another was to sow tens of thousands of mines throughout the gulf’s waters. The German navy patrolled these waters with torpedo boats, surface boats that were used to lay the mines, to escort larger warships, and to surface-patrol. From above, the Luftwaffe surveyed the routes and patrol areas favored by Soviet submarines.2 While the war between Germany and Russia was primarily fought on land, the battle for the Baltic shaped the land war. Until 1943 Germany controlled the Baltic Sea and laid more than 60,000 mines.

The combination of these tactics devastated the Soviet navy, sinking or damaging its submarines and many of its surface ships. Throughout the first few years of hostilities, the German navy enjoyed virtually free reign on and below the Baltic Sea. The U-boats sank enemy ships and interrupted sea traffic in the Baltic Sea just as it did in the Atlantic Ocean and North Sea. Moreover, the German Kriegsmarine’s control of the Baltic Sea meant the navy could keep the Wehrmacht fighting on the eastern front well supplied.

Admiral Karl Dönitz always wore his U-boat diamond-studded war badge and his World War One Iron Cross pinned to his dark blue uniform. Deeply involved in the daily operations of the German navy, Dönitz could be something of a micromanager. The admiral doggedly pursued his goal to protect the key ports of Gotenhafen, Danzig, and Kiel. His perseverance paid off: “It is important that we retain possession of the Baltic Sea, the waters in the Baltic and Norway,” he told Hitler and the rest of the naval leadership. He cited economic reasons, but it was also for military reasons.3

Dönitz hailed from Grünaw-bei-Berein, and like his predecessor, commander-in-chief of the navy, Erich Raeder, he too had served in the German Imperial Navy. In 1916 he entered the submarine service and commanded U–68. At the end of World War One his boat suffered from mechanical problems that forced him to surface in the middle of a convoy after sinking a large ship. The British captured Dönitz and held him prisoner until 1919.4

Upon release, Dönitz promptly returned to his navy career. He advocated a strong submarine force. In 1935, after the Anglo-German Naval Treaty was inked and the 1919 Versailles Treaty restrictions lifted, Dönitz once again had a command, this time of a U-boat flotilla. He spent time as rear admiral in charge of all U-boat operations. Then, on October 1, 1939, just a month after the Third Reich invaded Poland, Adolf Hitler promoted Admiral Karl Dönitz to Rear Admiral. His command was that of Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote (Commander of the Submarines).

Alexander Marinesko understood the challenge he faced when he assumed command of the Soviet submarine S-13 in 1942. The young officer from Odessa surely knew of the U-boats’ ruthless campaign against civilian and neutral ships: An early incident in the war alerted him to its extent. On September 3, 1939, just two days after the Reich invaded Poland, Captain Fritz-Julius Lemp of the U-30 patrolled the northwestern sector of the Irish Sea. There he spotted the S.S. Athenia 200 miles west of the Hebrides and fired on the British luxury liner without warning.5 The unescorted ship carried 1,418 passengers and crew on board, most of whom were Jewish refugees. Of all the passengers and crew, 300 were US citizens. Lemp’s attack killed 118 people: 69 were women, 16 were children, and 22 were American citizens.6 Thus, Captain Lemp fired the first shots of the Battle of the Atlantic. Lemp later received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, Nazi Germany’s highest military honor for bravery under fire.

The Germans were mindful that the unprovoked sinking of the Athenia would likely be compared to the World War One sinking of the passenger ship the RMS Lusitania, a British ship. The Nazis decided to cover up Lemp’s actions. They believed denying any involvement in the sinking was the best damage control. The Nazis also feared the sinking could draw the United States into the war, a development they wished to avoid this early on in the conflict as they didn’t want to engage on multiple fronts so soon. Hence, Joseph Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry tried to make it appear as if the British had sunk the Athenia to entice the United States to join them in war. Germany’s spin machine failed. The Allies were furious and accused Germany of flouting international laws of the sea and engaging in unrestricted submarine warfare, as it had during the First World War.

The Athenia became the first of many merchant and civilian boats on the receiving end of German attacks during the Battle of the Atlantic, between 1939 and 1945. Germany’s U-boats pursued and attacked British surface ships, destroying supplies. The United States officially declared war on December 8, 1941. In the early years of the war, German U-boats had to operate on the surface of the water for maneuvers under cover of darkness. They would dive to attack. But, in the summer of 1943, the Germans began to pull their subs out of the Atlantic—the Allies had better radar and better and more powerful depth charges. This led Admiral Karl Dönitz to push the idea of a super U-boat with Adolf Hitler.

The U-boat began as Nazi Germany’s agent of terror during the Second World War.7 Indeed, from the outset of hostilities, German U-boats menaced the Baltic Sea. After World War One, the German navy had faced restrictions on the number and size of boats German shipyards could build. According to the 1935 London Treaty, the German navy could not exceed 35 percent of the number of British surface warships. Yet the German navy was allowed to have an equal number of submarines as the British had. So, when Great Britain started rearming in 1936, Nazi Germany ramped up the construction of its U-boats.8

As supreme commander of the German navy, Admiral Erich Raeder supervised the build-up. Raeder served as the navy’s number one man until December 1942. Following an argument with Hitler about the Battle of the Barents Sea, Raeder suggested that either Admiral Rolf Carls or Admiral Karl Dönitz replace him.9 The Führer chose the 51-year-old Dönitz.

The new navy commander could focus on the Soviet navy since the US and British fleets were occupied elsewhere. Even so, the Russian submarine fleet presented no more than a pesky intrusion in the Germans’ side, at least during the early years.

At the start of the war Nazi Germany felt confident about its naval superiority.10 “No German officer who had fought the Russians in 1914–1917 had any real respect for their fleet. It is true that the ship’s crews knew well enough how to fire their guns, and in a tight corner they would fight bravely to the end,” wrote a vice admiral of the German Imperial Navy who sailed in the Baltic during World War One. From this admiral’s perspective, the Russians didn’t think quickly and didn’t exploit tactical and operational opportunities that were fluid during wartime. The German navy was confident to the point of arrogance, but it wouldn’t retain superiority for long.11 In fact, when Captain Alexander Marinesko attacked and sank the Wilhelm Gustloff, the Soviet Union and Germany had already been engaged in unrestricted warfare in the Baltic Sea since 1942.

Meanwhile, the Russian navy pursued its own build-up. After Vladimir Lenin died in 1924, Josef Stalin took a direct role in decision-making concerning weapons development and production.12 During the prewar years the Soviet regime stressed submarine development and construction, moving to increase the size of the entire Soviet fleet.13

During the uneasy days of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the German navy had used Soviet port facilities at Teriberka, just east of Murmansk. The navy welcomed these harbors as they offered safe haven for German blockade-runners trying to escape the British navy.14 In September 1940, the Russian navy built three battleships, one of which was about 45,000 tons. The Russians also started building several 2,800-ton submarines.15

Because whoever controlled the Baltic controlled vital supply lines, the German naval command grew somewhat obsessed about conditions in the Baltic Sea. On February 23, 1940, for example, General Wilhelm Keitel, General Alfred Jodl, and Commander Karl von Puttkamer fretted about how the “ice situation” froze German naval activity: “The Naval Staff considers the present time—after the conclusion of the economic pact with Russia— suitable for reviewing the agreements with Russia regarding the boundary line for warfare against merchant shipping. We cannot forgo control of the merchant traffic in the eastern Baltic.”16

The Russians wanted access to the sea, and occupation of the Baltic States guaranteed that by giving its navy a trio of virtually year-round ice-free bases at Revel, now Tallinn; Libau, now Liepaya; and Baltiski Port, now Paldiski. Ice plagued both the Reich and Russia. The winter of 1941–1942 was quite severe, causing Germany to postpone the training of new U-boat crews.17

In the spring of 1942, the German navy concentrated on stopping Anglo-American aid shipments to Russia; Russian convoys became target number one for the Third Reich. The German navy also launched various Black and Baltic Sea offensives to help the Wehrmacht push through Russia.18 To avoid U-boats, Allied convoys transporting war material for Russia no longer traveled the waters of the Arctic to Murmansk; instead, they passed through the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf.19

The German U-boats had at best another year of impunity before the Allies started to dominate the seas. In the spring of 1941 code breakers at Bletchley Park in England cracked the Enigma code. While breaking the code helped Americans and the British protect their vessels from the German navy, it initially didn’t do much to improve the strength and force of the Soviet fleet. For one, the Allies didn’t want the Germans to know they had broken the code.

In Germany, Adolf Hitler pushed Admiral Karl Dönitz to devise a plan for the eventuality of Russian boats breaking through the Gulf of Finland into the Baltic Sea. In turn, Dönitz assured the Führer that “control of the Baltic is important to us.”20

Retaining naval supremacy in the Baltic Sea allowed German surface ships and U-boats access to the Atlantic and the North Sea, and of course kept the Soviets at bay. Admiral Karl Dönitz considered the possibility of beginning submarine operations in the Arctic Ocean. Although this might have seemed an obvious alternative to the Baltic Sea for the Soviet Navy, harsh conditions and frigid temperatures severely limited operations.

“The arctic night is unfavorable for submarines as it renders it difficult to locate the targets. Winter weather, with blizzards, storms, and fog, has an adverse effect,” Dönitz told the naval command gathered at a meeting with Adolf Hitler.21 Ice can cover up to 45 percent of the sea in winter. The Arctic Sea rarely freezes over, but water temperatures average 4 degrees Celsius (39 degrees Fahrenheit). In addition to manmade obstacles, mines laid by the Germans filled the Arctic Sea.

Moreover, Admiral Dönitz and his immediate subordinates decided not enough air reconnaissance existed to make it worthwhile. Submarines in World War Two relied on air reconnaissance to help guide them and locate targets, as well as for protection. Since the submarines still had no radar, they used the radio to communicate with aircraft. Those communications could be intercepted.22 The Arctic also posed a problem because the currents in the sea were simply too strong.

At least ten Russian submarines operated in the Baltic Sea region. However, not one submarine had so far successfully attacked a German vessel. As winter set in, Dönitz said, the possibility that any of those Soviet ships still able to operate might break through diminished. During Germany’s invasion of Russia, German U-boats had made quick sport of the Soviet submarines: the Soviet Baltic Fleet lost 12 subs between June 23 and June 26. To protect against further losses, the Russian navy moved the remaining units of the Baltic Fleet to the North Black Sea before the inland waterways froze.23

“When war against Russia broke out, eight boats were dispatched to operate in the Baltic. There they found practically no targets and accomplished nothing worth mentioning. They were accordingly returned to me at the end of September,” Dönitz wrote in his memoirs about early summer 1941.24

Throughout the war, the United States closely watched and reported on the ever-increasing Russian and German military presence on the Baltic Sea. In 1939 Ambassador Laurence Steinhardt wrote to Secretary of State Cordell Hull to alert Hull not to trust the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. The Soviet government’s agreement with Nazi Germany about the Baltic States—namely the expulsion of millions of Baltic Germans according to Molotov-Ribbentrop pact—appeared to have been part of the Soviet’s long-time strategic aim to gain access to the sea, he said. In addition, the Russian navy wanted to secure Soviet naval and air bases on the Finnish islands in the vicinity of Kronstadt and possibly a base at Hanko as well.25 Controlling these locations would help them launch and repel attacks against Germany.

At the time, many Russian warships found themselves effectively hostages of Sweden. In the early fall of 1944 Sweden closed all its territorial waters in the Baltic to foreign shipping because of Allied pressure. This had the effect of hurting German communications, and also that of the Soviets.26

The closure of Sweden’s territorial waters wasn’t the only thing hindering the Soviet navy. Earlier in the war the Germans had heavily mined the Gulf of Finland. Yet, in spite of an estimated 13,000 mines, Russian submarines based in Kronstadt broke through and made it to the open waters of the Baltic Sea.27 This was of little concern to the Germans. Most in the German naval high command regarded this as a bit of a fluke, still believing that generally mines would heavily damage Russian forces.28 This fit in with Germany’s plan to prevent Russian naval forces from leaving the Gulf of Finland.29

Also in 1944, the German and Finnish navies met in Kiel, Germany, to discuss completely blocking the Gulf of Finland.30 They had finished laying steel nets, which reached to the bottom of the sea by the spring of 1943. These double antisubmarine nets, called walross, or walrus, were successful; Russian submarine attacks on German shipping ceased until about autumn 1944.31 Attacking German ships posed a peculiar challenge because the Luftwaffe was a constant deterrent—until June 1944, when the Soviet Union achieved air supremacy in the east and the Americans and British attained it in the west.

Consequently, in August 1944, the Nazi leadership decided to only use small vessels in the Baltic to fight growing Russian naval power. Mines became the region’s most effective weapon. Only two or three Russian submarines broke through the minefields into the Baltic compared with at least 20 others that were destroyed in trying to reach it.32 The Germans also used floating mines to blow up the many bridges that spanned the region’s rivers. To defend against these German floating mines, Soviet ships tasked artillery watches with identifying and destroying suspicious objects floating on rivers and sea. The Russian ships attached old wooden barges at their bows as rudimentary bumpers that would take the force of an explosion before the mine could damage or sink a ship.33

In 1944 the Soviet Union opened its counteroffensive against Nazi Germany. Not only did the Red Army push back the Wehrmacht on land, the Russian navy began to exert control along the Baltic coast. The Soviet navy took advantage of the winter of 1944 and 1945 to establish submarine bases all along the Finnish coast.34 Finland allowed the use of its harbors and anchorages under the shaky armistice between the two nations for as long as the war with Germany lasted. By the end of October 1944, Helsingfors and Nadendal, and even Hanko, operated as Soviet naval bases.

Submarine patrols in the Baltic Sea stopped when the Germans withdrew from eastern portions of the Baltic coast. About 2 million soldiers, Gestapo troops, military dependents, and other Prussian and Pomeranian civilians needed to be relocated after German defensive positions along the coast collapsed.

In 1944 the Russians reclaimed the Black Sea port of Odessa, Captain Alexander Marinesko’s childhood home. This Soviet victory didn’t end in Odessa; rather, it helped push the Soviets forward. It was part of a powerful Red Army offensive designed to push the Wehrmacht out of the Crimea. If successful, the Soviet fleets would have the run of the entire Russian Black Sea coast.35 During the offensive, the Soviet navy captured many German sailors. Descriptions of these captures reached American shores: “Captured German submarine crews were described by the Americans and Allies as no longer ‘spitting in our eyes like they did when they were cocky.’ There is now an appreciable loss of spirit in the crews of the U-boat which our men have recently captured. . . . Now they seem to realize the cause is lost.”36

Yet, in spite of the Soviet victories, and in spite of the fact that the Soviet navy failed to sink or damage any of the major German vessels employed at the time in the Baltic Sea, the German forces were able to retreat from the area’s coast.37

Even while the Soviets regained some control of the Baltic Sea, the Germans still dared to use its waters as a training ground for their new U-boats. The Baltic training area, known as Baltic Station, was one of Germany’s three key naval bases. As late as January 1945, a new generation of German U-boats had test runs in the Baltic and training was going on at full speed.38

Before World War Two started, Soviet submarines often worked in pairs and often gave away their positions in frequent radio communications with command headquarters located on shore.39 One Soviet submarine captain described the Soviet navy as facing some of the most “inconceivably difficult conditions,” during the war. Between net barriers, minefields, and constant attacks from the Luftwaffe, the Soviet navy simply had to contend with incredibly difficult challenges.

The Soviet navy sought to reduce these difficult circumstances and to mitigate losses, and so Soviet submarines initially hunted individually in contrast to the German “wolf packs.” The Soviet submarines kept a distance of up to 5 miles from each other so they wouldn’t endanger one another, and for the most part, they relied on aerial reconnaissance to locate targets. Each submarine patrolled its own territory, known as a box, along German shipping routes. At first most attacks happened in the daylight since Soviet submarines didn’t have radar. However, later in the war the Russian Navy increased its nighttime attacks.40

During the war’s early years, Soviet subs waited passively in preset locations until a target appeared. Unsurprisingly, this strategy didn’t yield many hits.41 The strategy changed when those below the sea started communicating with reconnaissance planes above the water. However, because the planes needed visual sighting, daylight attacks outnumbered nighttime attacks. Of course, once submarines began using radar, nighttime attacks increased.

During the latter part of the war, the Soviet military pushed back their German enemies on land too, as the Russian armies choked off many possible escape routes. That left the Baltic Sea as the most viable refugee option. As the United States Office of Strategic Services reported from its Stockholm station during the period January 24 to 30, “nine ships totaling 18,500 tons passed through the Great Belt northward bound and during the same period seven ships totaling 14,500 together with a ten thousand ton hospital ship.” The Wilhelm Gustloff was among these boats. But the United States didn’t yet know the size of the Soviet’s prize.

Meanwhile, German military strategists understood they needed to protect the coastline along the Baltic Sea to help thwart Russian incursions onto their land. They also needed to secure the Baltic training areas and U-boat building harbors, such as Gotenhafen and Danzig.42 They employed coastal artillery and defensive mine barrages, and they mined the waters to close all entrances to the Baltic Sea. This, they hoped, would hamper merchant shipping and vessels used to supply Russian civilians and troops.43

The lone wolf strategy of the Soviet navy suited Alexander Marinesko, who now moved his boat silently along the Baltic Coast, hunting for a suitable target. It is the end of January and he has received word that the Germans will be stepping up naval operations in the Baltic. Back in Gotenhafen the Wilhelm Gustloff prepared to leave. The Hansa, also anchored in Gotenhafen, was supposed to escort the former KdF cruise liner to safety in Kiel. Hundreds of naval personnel and thousands of refugees waited— anxious and desperate.

This bell is one of the few artifacts that was recovered from the Wilhelm Gustloff. Author’s collection.

Seaman Walter Salk, 19, of Essen, Germany, perished on the Wilhelm Gustloff. It took his parents more than a year to learn his fate. Walter’s older brother, who served on a U-boat, was killed a year before. Courtesy of Rita Rowand.

Inge Reuter, sister of Helga Reuter Knickerbocker. The last image Helga had of Inge was her floating away in the dark night. Courtesy of Helga Reuter Knickerbocker.

The Tschinkur family; sisters and cousins with father Herbert Christoph and Serafima, in Gotenhafen. Courtesy of Irene Tschinkur East.

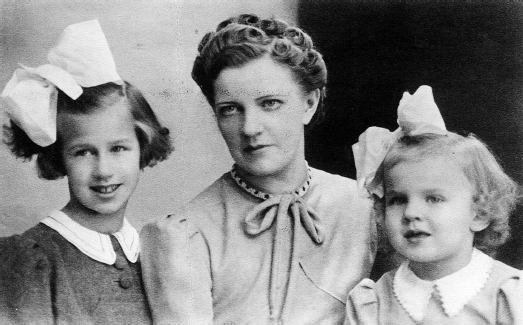

Left to Right: Irene Tschinkur, Serafima Tschinkur, and Ellen Tschinkur. The girls and their mother survived the sinking. Courtesy of Irene Tschinkur East.

Lighting Christmas Advent candles during a blackout in Gotenhafen. Left to Right: Ellen, Evi, and Irene Tschinkur. Evi would not survive the sinking. Every few years Irene takes out an advertisement with her picture in her hometown paper as a way to remember and memorialize her cousin. Courtesy of Irene Tschinkur East.

The Wilhelm Gustloff. Author’s collection.

Helga Reuter Knickerbocker. Courtesy of Helga Knickerbocker.

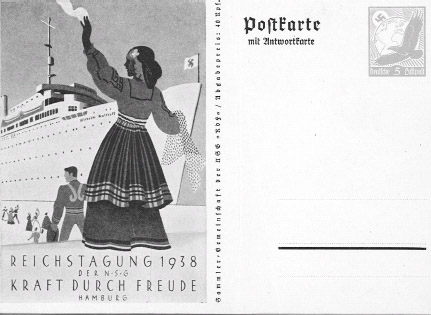

“Strength Through Joy” postcard celebrating Wilhelm Gustloff. The Nazi’s Strength Through Joy program was designed to bring leisure to the German middle and lower classes who weren’t able to afford a vacation on their own. Cruise liners such as the Wilhelm Gustloff were part of this program. Author’s collection.

The Reuter furniture factory and showroom in Königsberg. Next door a store had been named “Enemy.” The Nazis commandeered the factory and turned it into a uniform factory. Russian prisoners of war worked in the factory. Courtesy of Helga Knickerbocker.

Staff working at Baltic Home, a place for newly repatriated ethnic Germans when they first arrived to East Prussia from Baltic States such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact hundreds of thousands of Baltic Germans were moved to East Prussia. Courtesy of Irene Tschinkur East.

In 1945 Serafima Tschinkur, mother of Irene and Ellen and aunt of Evi, wrote to family friends about the sinking. The letter was recently recovered in a suitcase in Paris, France. Courtesy of Irene Tschinkur East.

Nearly 70 years after the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff, Horst Woit stands in front of his lakefront home in Ontario. A day doesn’t pass that Horst doesn’t think about the night his knife saved him, his mother, Meta, and the people inside his lifeboat. Courtesy of Cathryn J. Prince.

Meta Woit, Horst Woit’s mother. Meta moved to Canada with her son after the war. Courtesy of Horst Woit.

Milda Bendrich and baby Inge Bendrich Roedecker, Gotenhafen. Just two years old at the time of the sinking, Inge remains the youngest known survivor of the Wilhelm Gustloff. According to a letter from Milda, Inge didn’t cry once during the entire ordeal. Courtesy of Inge Roedecker.

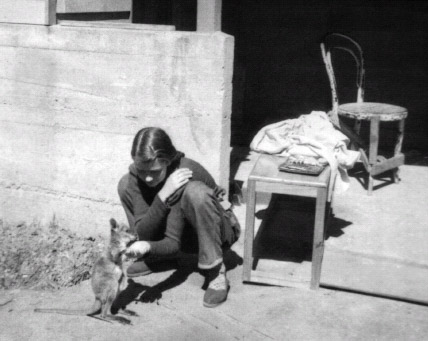

Inge Bendrich Roedecker after the war on King Island, Australia, with pet wallaby Skippy. Inge’s father spent nearly three years in a Soviet prison camp after the war. After he was released the family moved to Australia. Courtesy of Inge Roedecker.

Eva Dorn Rothschild in Ascona, Switzerland. A music student at the University of Leipzig when the war broke out, Eve joined the Women’s Naval Auxiliary. She was helping in the ship’s hospital when the torpedos hit. Courtesy Cathryn J. Prince.

Evelyn “Evi” Krachmanow, cousin of Irene and Ellen Tschinkur. The three cousins were very close, and Evi’s death left an impossible hole to fill in Irene and Ellen’s hearts. Courtesy of Irene Tschinkur East.

Alexander I. Marinesko, commander of the S-13. The sailor from Odessa knew he needed a significant “kill” in order to redeem himself in the eyes of his superiors. Courtesy of Edward Petroskevich.

Statue honoring Alexander I. Marinesko in Kaliningrad, Russia (formerly Königsberg, East Prussia). Today the Russians consider Marinesko a hero for sinking the Wilhelm Gustloff.