NIKITA KHRUSHCHEV WAS JEALOUS OF AMERICA’S MISSILES. A voracious reader, the Soviet leader made sure to procure the latest technical papers his KGB agents offered about the status of the US missile program. He saw evidence that the Americans were doing things that his physicists had told him were impossible.

Since rising to power in 1953 after the death of Joseph Stalin, Khrushchev had worked hard to remove the worst extremities of his predecessor—not just by curbing mass killings and gulag deportations but by encouraging an intellectual liberalization of sorts.

He was obsessed with missile technology. So much so that, starting in 1955, he scrapped much of the Soviet Navy’s fleet, believing it to be obsolete and pointless. The military hated him, seeing their leader as destructive and shortsighted.

“We cannot say my father was focused on missile technology because it was his passion—it was one of our necessities,” explains Sergei Khrushchev, an academic who edited his father’s memoirs and now has American citizenship. “It was important for my father and for the Soviet Union, and for all of us, because it was one way to prevent an American first strike. The missile technology gave this possibility to the Soviet Union to get a lead. Especially ICBM missile technology, because it was the only way the United States was accessible to us.”

Sergei worked on missile guidance systems himself for many years. “We were more or less on the same level as the United States on missiles, generally. On guidance systems, the United States were some steps ahead. In the engines, we were a little ahead.”

Multiple accounts published over the years describe Nikita Khrushchev telling his subordinates that the next war, if and when it came, would be a missile war. A scene in William Taubman’s Khrushchev, The Man and His Era depicts the Soviet leader lecturing his senior officers in exactly this point. At a missile launch at the USSR’s Kapustin Yar weapons development facility in the desert of Astrakhan, a hundred miles or so east of Leningrad, Khrushchev spoke about discarding almost all conventional armed forces to drive as much resource as possible to missile development, according to Taubman. The assembled ministers and generals listened in stunned silence.

In the summer of 1958, Khrushchev was summering in Crimea at the Nizhnyaya Oreanda health resort, where he gathered top officials—including his top rocket scientist, Sergei Korolyov—for informal brainstorming. Korolyov was symbolic of the times. A Ukrainian, he had spent two years in an Eastern Siberian gulag after falling afoul of Stalin, yet now he was in the most exclusive resort in his homeland sitting at the top table with the new leader. He was still not on great terms with the leadership, however.

Khrushchev believed that when it came to missiles he knew more than the top military commanders who would be using the new technology if and when war broke out, according to Taubman. One of Khrushchev’s concerns, for example, was that the USSR planned to have its fleet of nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) stationed above ground. Surely they would be vulnerable to preemptive strikes by the Americans, the Soviet leader argued. Why could they not be launched from underground silos, hidden from view?

Korolyov insisted this was a nonstarter. The missiles would burn up in the silo due to the heat from the gasses emitted. They would never get airborne. Khrushchev was unconvinced, arguing that the gas would dissipate in the space between the missile and the steel cylinder. Khrushchev realized he had no right to force the idea down their throats, so he let the matter drop. Not long afterward, sometime late in 1958, Khrushchev found a technical report in an American science journal explaining that President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s researchers already knew how to launch giant ICBMs from underground silos. After reading this, he supposedly “rejoiced like a child,” commanding his missile experts to read every possible scrap of information about America’s missile program—and, presumably, the individuals engaged in it.

The state of the Soviet missile program was the central debate in global geopolitics of the day. After World War II, Wernher von Braun, the developer of the V-1 and V-2 flying bombs used to such devastating effect by the Nazis, was lured to America. The Russians, meanwhile, captured a group of Braun’s underlings and created the Kapustin Yar facility at which they could develop their ideas. The German scientists were held as prisoners for six years from 1946 until 1951, during which time they trained a group of local Russians to take over their work.

Braun had been cleansed of his Nazi past by American officialdom, in order to facilitate the work they wanted him to do. The public would not have tolerated an ideologically committed Nazi serving in public office. The military was more pragmatic, however, and more concerned with securing the best talent.

Braun and his team were shipped around to different bases, including the US Air National Guard base in New Castle, Delaware; Fort Strong, in Boston Harbor; and the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Eventually, by the start of the Korean War, they too had their own dedicated site in Huntsville, Alabama. Braun’s team complained, only half-jokingly, that they were “prisoners of peace.”

America was not what they expected. Braun had been in charge of thousands of scientists at Peenemunde, on Germany’s Baltic coast. Now he was made to answer to Major Jim Hamill, a pimply twenty-six-year-old—who encouraged Braun to avoid even speaking to everyday Americans for fear that his obvious German accent would cause offense. His engineers complained of the “tasteless” American food and begged for linoleum to cover the bare floorboards in their labs.

Whereas wartime Nazi Germany had thrown infinite amounts of cash at his ideas, Braun claimed he was being starved of resources in the United States. He had been developing rockets based on old V-2s that had been seized in Germany and shipped to America. Although he had proposed countless ambitious new rocket designs from the moment he set foot on US soil, and started to talk about conquering space, in the first few years most of Braun’s projects were knocked back on the grounds of cost.

It all proved fertile ground for conspiracy theories. Aided by the public musings of the ambitious Democratic Party senator from Missouri named Stuart Symington, the notion of the “missile gap” entered the public discourse. The Russians, the likes of Symington stated, were years ahead of America in development of next generation nuclear weapons that could be launched from the Soviet Union and take out European cities.

With the benefit of hindsight, the consensus view seems to be that Symington—a former chief executive of Emerson Electric—was a paid lobbyist for the American defense industry. Braun, in his attempts to secure more funding for his ever more grandiose schemes, was probably happy to go along with the narrative of paranoia.

President Eisenhower, the former leader of the Allied forces in Europe, knew a thing or two about the relative strengths of his own military and that of the Soviets. He never believed in the “missile gap,” nor the “bomber gap” theory that preceded it.

Eisenhower’s take on future warfare was identical to Khrushchev’s. His New Look defense policies were about spending less money in total, while splashing more money on the most advanced technologies—the science that would win future wars. Yet he was fighting against vested interests left, right, and center, not least from congressmen fearing job cuts at shipyards or munitions plants in their local districts.

Eisenhower knew he had the technological edge. Khrushchev knew that too. In public, the Soviet leader was only too happy to make public statements professing the USSR’s military lead. He developed a habit of test-launching missiles at Kapustin Yar immediately before every foreign trip, helping to build his international reputation as a badly-dressed vulgarian with a short temper. In private, he berated his senior officials for falling behind the Americans.

Eisenhower was being subjected to political potshots based on made-up intelligence. His time spent on the golf course came to be associated with complacency about the Soviet threat he refused to acknowledge.

Dudley and Virginia Buck with their mother.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

The Buck family in Santa Barbara, California. From left to right: Grandma Delia, Grace, Virginia, Dudley, and Frank.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

Buck and his Aunt Gladys photographed on his graduation from the V-12 program, July 7, 1947.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

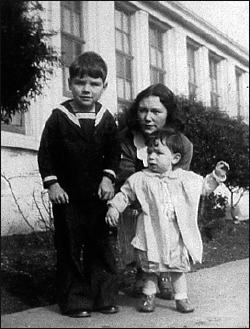

An autographed photo of Scout Troop 31, led by Scoutmaster Buck, with J. Edgar Hoover.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

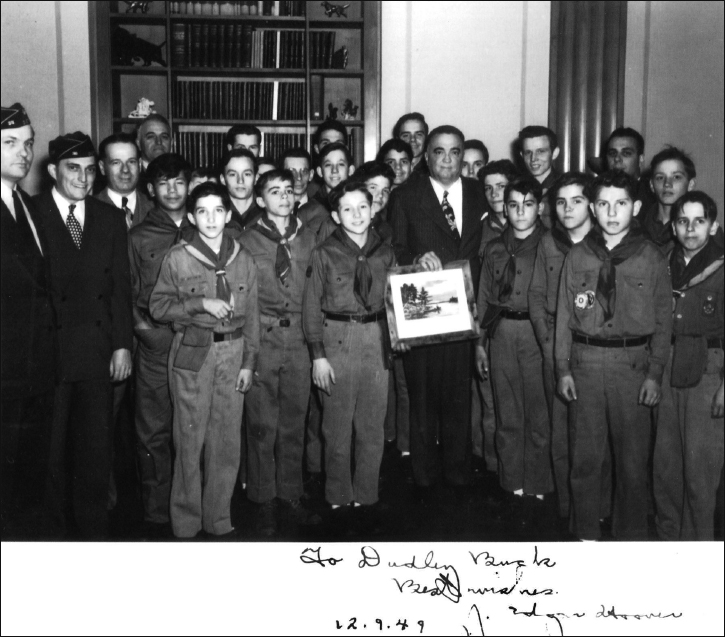

Two official letters from the US Army signed by Captain Edward Bray granting permission for US Civilian Dudley Buck to carry a concealed weapon in Germany “while in the performance of his duty,” on two separate periods in the spring of 1950.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

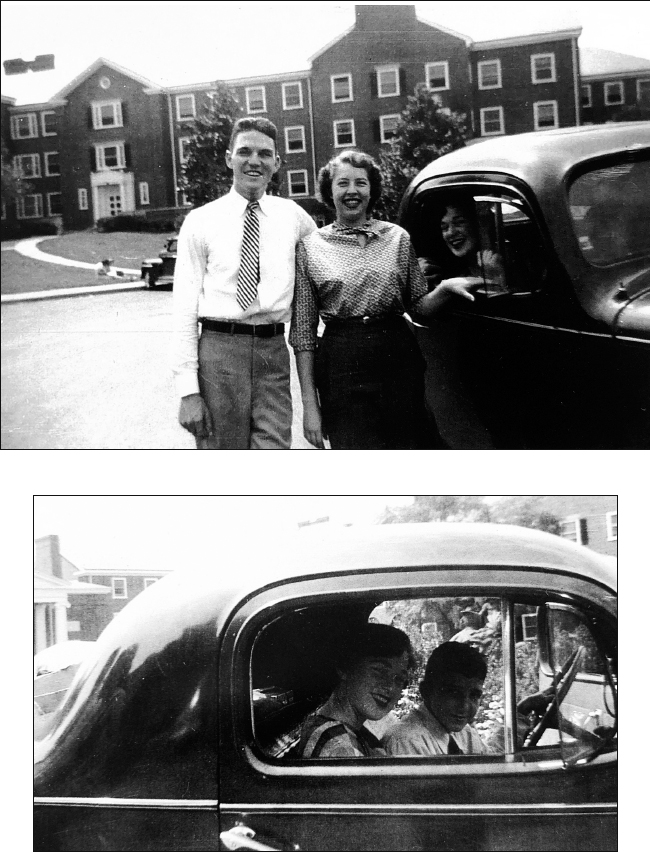

Dudley and Virginia Buck and Glen Campbell move to Boston, Massachusetts, 1949.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

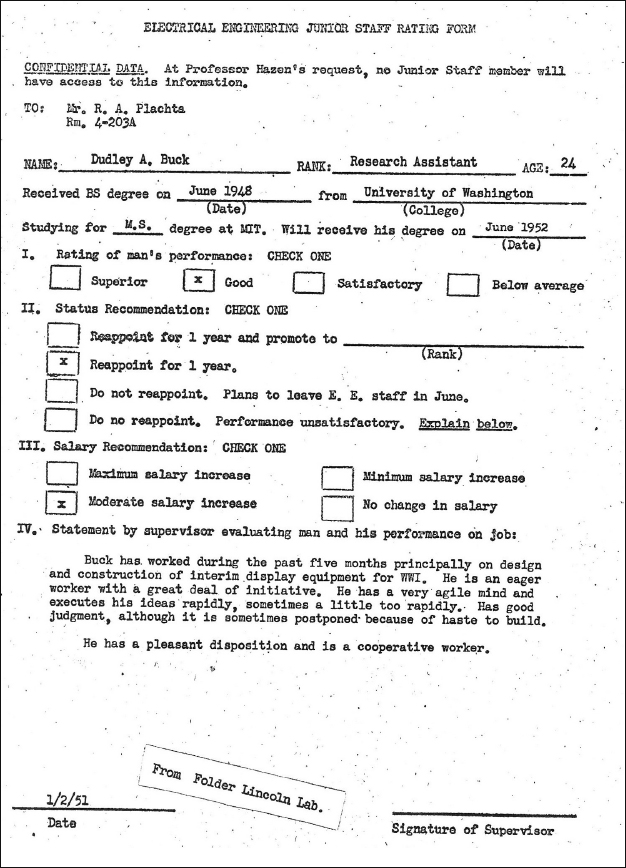

A copy of Buck’s electrical engineering junior staff rating, dated January 1951—an overall positive evaluation noting “good” performance and recommending a moderate salary increase.

(Credit: MIT archives)

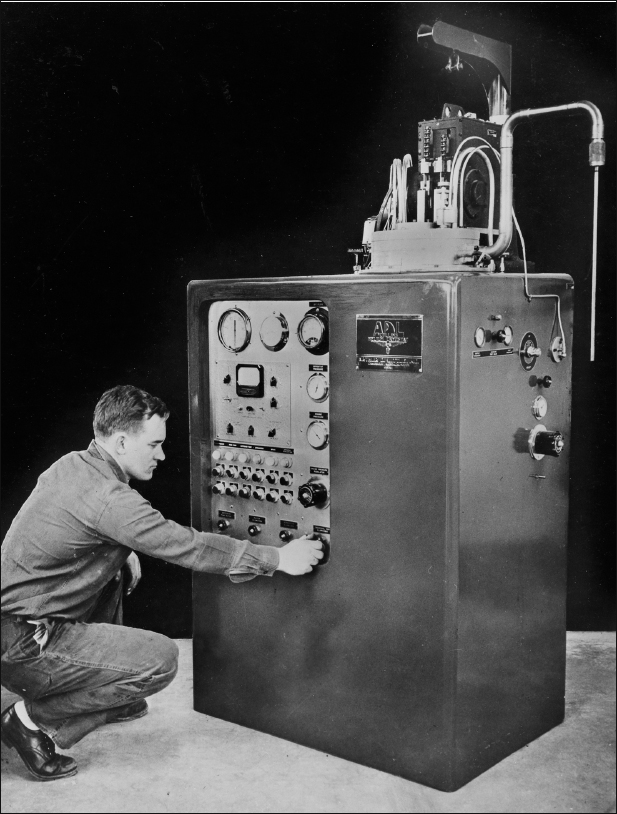

The Cryostat, a machine built by S. C. Collins at MIT to liquefy helium. Experiments with the helium produced by this machine revealed that some metals became superconductors for electricity once they were steeped in a vat of liquid helium; this revelation inspired Buck to begin his research into using these superconducting materials to create a miniscule and ultrafast computer, leading to his invention of the Cryotron.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

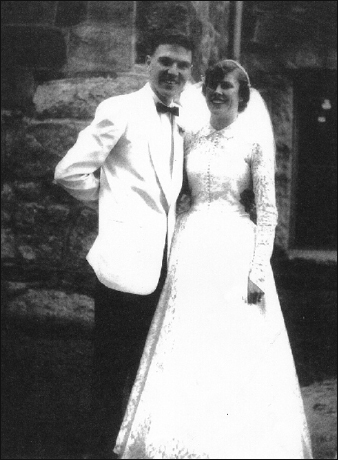

Buck and Jackie Wray on their wedding day, June 6, 1954.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

Buck and Jackie attend the wedding of Buck’s sister, Virginia, and Georg “Schorry” Schick, September 4, 1954.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

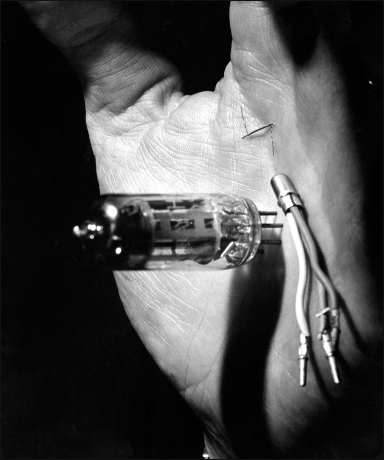

A single cryotron. On February 18, 1954, Buck had his first successful test of the cryotron, in which the device switched from conducting an electrical current to resisting it.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

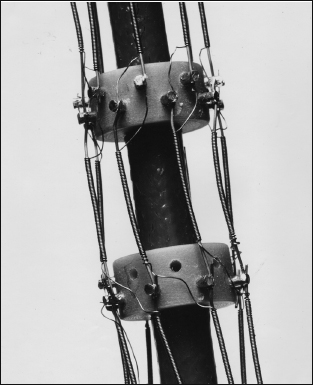

A cryotron, a “superconducting switch,” could be hooked up to a circuit.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

(Credit: Buck family archives)

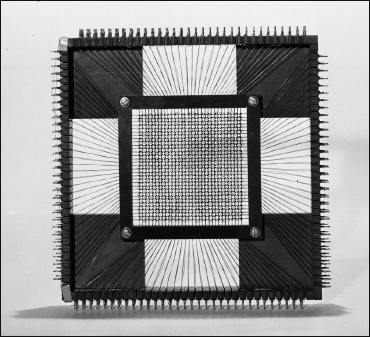

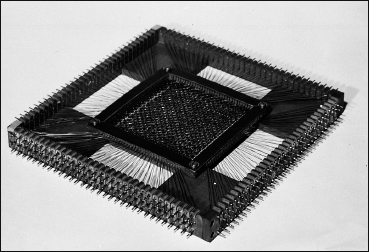

Magnetic core memories, developed at MIT by Buck and his colleagues. Magnetic core memories allowed data-processing machines to handle vast amounts of information and were used in IBM computers in the 1950s. The invention of this technology led to a legal battle between IBM and MIT.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

By 1956, Buck and his colleague, fellow MIT engineer Ken Shoulders, had developed his cryotron from two thin wires to a thin film made of superconducting materials, which increased the speed at which the switch could flip between “zero” and “one.”

(Credit: Buck family archives)

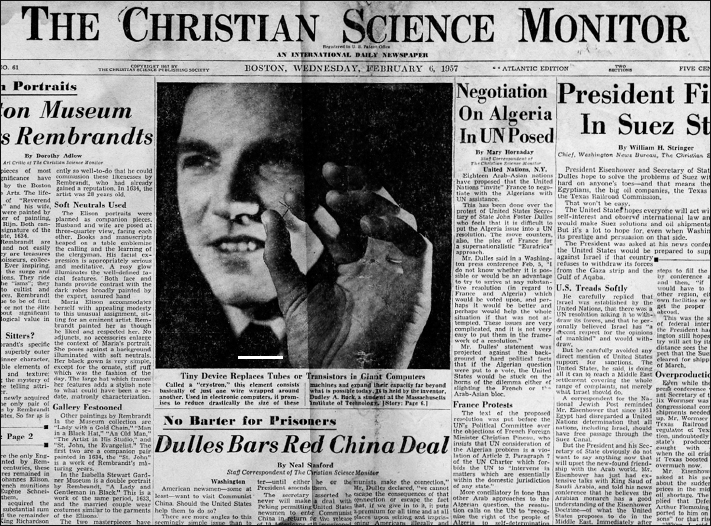

Buck appears on the cover of The Christian Science Monitor on February 6, 1957, for his work on the cryotron.

(Credit: The Christian Science Monitor)

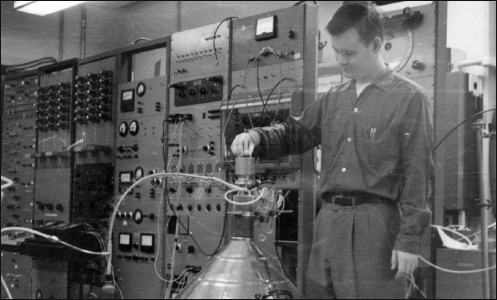

Professor Buck and his undergraduate research assistants, including Allan Pacela and Chuck Crawford, in his lab at MIT’s Building 10 in the summer of 1958.

(Credit: Supplied by Allan Pacela)

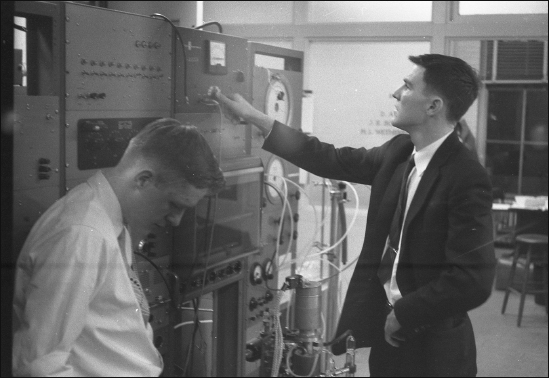

Buck and Chuck Crawford in the Building 10 lab at MIT.

(Credit: Supplied by Allan Pacela)

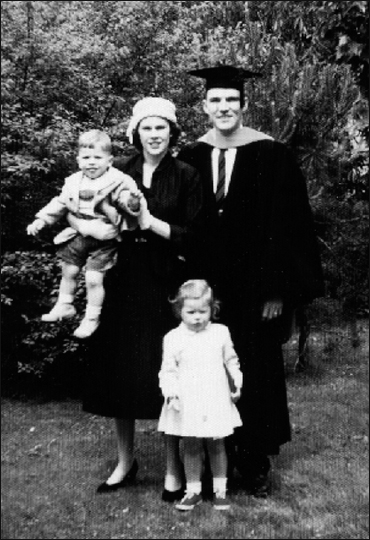

Buck receives his doctorate, here pictured with his wife, Jackie, and children Douglas and Carolyn, 1958.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

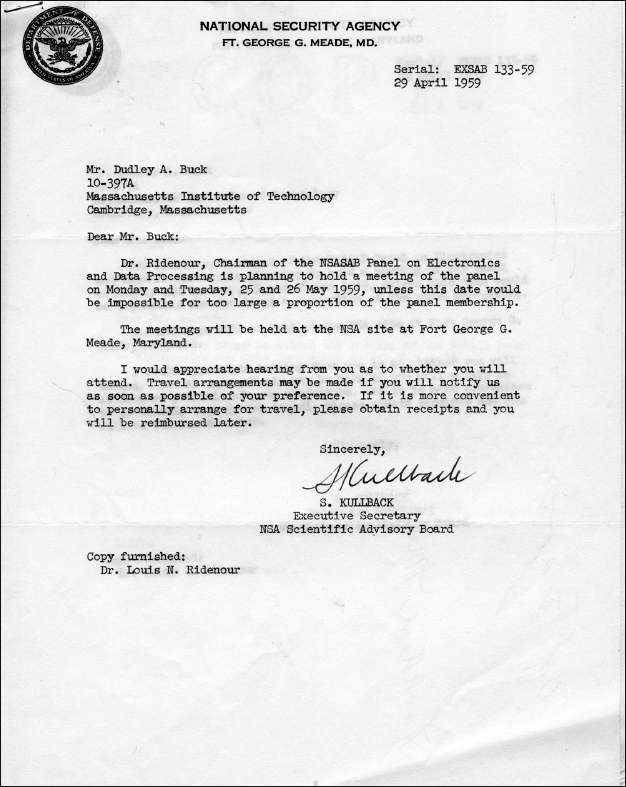

A letter (dated 29 April 1959) from Solomon Kullback, Executive Secretary for the NSA Scientific Advisory Board, inviting Buck to attend a meeting on electronics and data processing, hosted by Dr. Louis N. Ridenour at the NSA site.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

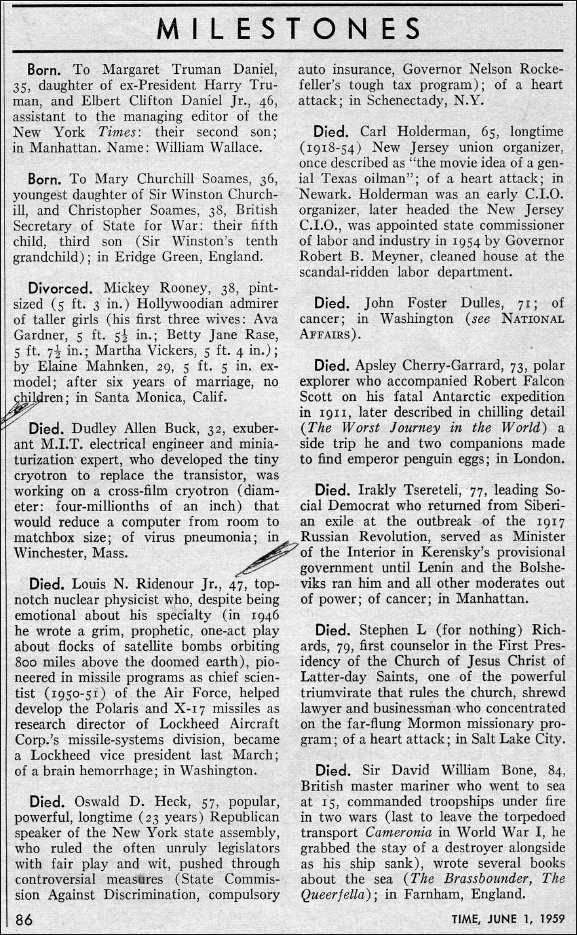

TIME reports on the deaths of Dudley Buck and Louis N. Ridenour, June 1, 1959.

(Credit: TIME magazine)

Dudley Allen Buck, April 25, 1927–May 21, 1959.

(Credit: Buck family archives)

The same narrative would eventually help drive John F. Kennedy to the White House, and then set the scene for the Cuban Missile Crisis. The debate over whose missiles were better, and their respective range, was central to Khrushchev’s desire to place missiles in the Caribbean.

Eisenhower’s response to the missile conspiracy theories was militarily pragmatic: he would procure evidence to disprove the theories.

In August 1953 the American president asked a favor from Winston Churchill, the reelected British prime minister, requesting that the Royal Air Force fly over the Kapustin Yar research base to see what it could see. “They came back with their planes shot full of holes and allegedly told the Americans that if they wanted that sort of thing done they could jolly well do it themselves,” claimed a declassified NSA report by Cecil Phillips and Lou Benson on UK and US efforts to break Soviet intelligence.

The CIA experimented with floating high-altitude balloons, equipped with cameras, across Soviet airspace. Of the five hundred balloons that were sent, only forty-four were ever recovered once they made it to the Far East. Their pictures yielded little information.

Eisenhower was convinced that technology could help him get to the bottom of the problem. In July 1954 he asked James Killian, the president of MIT, to set up a special committee to investigate the available options for surveillance of Soviet missile sites a little more thoroughly. It was dubbed the Surprise Attack Panel, its objective being to prepare against a surprise attack rather than orchestrate one.

Killian invited fellow Bostonian Edwin Land, the inventor of the Polaroid camera—and Virginia Buck’s old boss—to join him on the panel.

The solution they agreed on was a Lockheed-built high-altitude plane, based on the fuselage of the F-104 Starfighter, with a specially built Polaroid camera inside. The U-2 spy plane would be dressed up as a civilian project and run by the CIA. On December 9, 1954, Eisenhower signed off on a $54 million order for twenty of the aircraft.

Yet the U-2 could only provide intelligence. It did nothing to advance America’s efforts to build its own missiles, or keep them flying straight. When it came to that problem, Dudley Buck was increasingly in demand.

BUCK’S CRYOTRON, AS it was envisaged in its final state, had a particularly clear use for the military. If Buck could build a cutting-edge computer that could fit in a box measuring one cubic foot, he could build a computer that could fit inside a nuclear missile. If he could fit a computer inside a missile, it must surely be possible to use that computer to correct and adjust the missile’s path in order to guide a nuclear payload directly to its target.

A properly guided nuclear missile would have been a big step forward. In spite of the propaganda, both the Soviet Union and the United States were still struggling to build missiles that could be directed at a target with any degree of certainty. If either side were to attempt to launch its missiles in anger, who knows where they would have ended up or whom they would have killed.

Buck’s cryotron was starting to be talked about among the senior levels of the scientific community at the exact moment that missile paranoia was coursing through the veins of Washington, DC. Just as the U-2 order was being placed, Buck came to Washington to give an updated brief to the NSA about the progress on the assorted cryotron projects.

Before the cryotron was even fully operational in lab experiments, Buck started to be bombarded with questions about its potential use as a missile guidance system.

Experts at the Ballistic Research Laboratories at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland—one of the sites where Braun and his team were stationed when they first came to the United States—started to drop in regularly to see Buck’s lab, diary entries show.

Many of the engineers who had tried to hire Buck over the years had by this time been recruited into the missile effort, including Sam Batdorf, who had been behind Westinghouse’s big-money offer to Buck.

As missile technology became the new priority and the area where scientists could secure substantial salaries, Batdorf secured a post as head of electronics at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation’s missile systems division in Sunnyvale, California. While his colleagues were working on the U-2 nearby in Burbank, Batdorf was among those at Lockheed trying to build missiles.

As Batdorf wrote to Buck in December 1956,

I wonder if you could bring me up to date on the status of your work on the Cryotron. As I recall the last time we discussed this you had not yet whipped the problem of its slow speed but had some promising ideas based on evaporation techniques.

The reason I ask this is that we are interested in computers for use in airborne and ballistic missiles. In such applications weight, size and low energy consumption are of prime considerations. On the other hand, of course, all of these factors have to be rated in terms of the amount of computation that can be done per the unit of time by the device in question. We have also the problem of processing large volumes of data on the ground as discussed in the Beacon Hill Studies.

If the present state or the promise of the Cryotron warrants it, I believe we should look together into the matter of exploiting this approach. Therefore, if this turns out to be the case, I would like to be advised as to how we should proceed to get you out here for a conference.

Buck replied that his work was a long way from complete, but was moving along swiftly:

There is one commercial exploitation of the device being made at Arthur D. Little Inc. of Cambridge, Massachusetts. They have a contract with the Department of Defense to build a large unit containing approximately 250,000 cryotrons. The device is a type of function table which can give a yes or no answer as to whether or not a given 25-bit word is in the unit. The frequency of interrogation will be 100 kilocycles. The unit will occupy one cubic foot exclusive of the liquid helium container and about 2 racks of electronic equipment needed to drive and sense the unit. A feasibility model is at present under construction and indications look good. The 25,000 flip flops contained in the devices are still of the slow variety. The entire unit requires about 1 and 1/2 minutes to fill from punched paper tape. If, in your missiles systems division you have any use for a cryotron recognition unit of this type, I would suggest you get in touch with Dr. Howard McMahon of Arthur D. Little.

I am confident that it will not be very long before high speed cryotrons will be available. Two companies outside of MIT have already observed superconductors to change from one state to another in less than 0.1 microseconds. One company, in fact, believes they are able to switch superconductors from superconducting to normal in 8 millomicroseconds. I would very much like to keep in touch with you, and if I am out your way this summer, I would very much like to drop in for a visit.

Batdorf’s letter inquiring about the cryotron’s suitability as a missile guidance system came three months after Life magazine had proclaimed to the world that the gadget would eventually perform this role. Buck already knew Batdorf’s new boss.

Louis Ridenour was one of MIT’s most celebrated alumni, and he had been immersed in classified government projects for many years. He was a big man with a big reputation—known for his ability to crash through the hierarchy of the American military to get projects off the ground. During World War II, Ridenour had led the team in MIT’s radiation lab, which developed the SCR-584 radar—a lighter, more accurate radar that helped to sway the course of the war. When it went into service in 1943, it superseded every other radar system in the Allied forces and was carried to the front in specially built trailers that doubled as remote operating stations.

It was Ridenour’s radar that had helped Britain fend off the V-1 bombs that were used to attack London in the middle part of the war. Once the radars were installed on the gun batteries of England’s south coast, the success rate in shooting down the “flying bombs” rose from about 17 percent to 60 percent. Ridenour was sent to Britain himself to oversee the deployment of his device. He then had a hand in the development of a new radar system that could be installed in a plane, which facilitated bombing raids in dense cloud cover. The system, nicknamed Micky, was installed on the two B-29 bombers that dropped the Little Boy and Fat Man atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

At the end of the war, Ridenour left MIT to set up the computing department at the University of Illinois. He was also appointed chief scientist to the newly created US Air Force, and the chairman of the NSA’s scientific advisory panel on computers. Ridenour wrote the first manual on how to build and operate radar sets—the same book a young Dudley Buck had used as a student when he built his own radar with parts stolen from the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington, near Seattle.

It was also Ridenour who championed the idea of using private companies to develop America’s scientific prowess. He argued that competition, and the profit motive, were powerful drivers to problem solving. Even if there was some duplication of effort, multiple competing teams were much more likely to come up with new ideas than were big, centralized bureaucratic projects like those run by the Russians.

Buck appears to have first met Ridenour in Washington, DC, while he was still working on codebreaking machines. Curiously, Ridenour was granted a leave of absence from the University of Illinois for military reasons at exactly the same time Buck was seconded to work on his covert missions for the CIA. There is a possibility that they were sent behind the iron curtain together on a special project, possibly to negotiate jointly with Konrad Zuse.

What is clear, however, is that by the time Buck had developed the cryotron, Ridenour’s name was appearing regularly in his diary. They had a meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey, a few weeks before Buck got married—a meeting that looks curiously like it may have been his bachelor party. Buck then spent a day with Ridenour at his lab in California while he and Jackie were on their honeymoon.

At the time Ridenour had moved into the private sector. He was working with International Telemeter in Santa Monica—the first company in the world to launch pay-TV services. International Telemeter had an encryption system that could scramble and descramble television signals. The small number of households who signed up for the system bought a box to sit on top of their television set, with a coin-operated meter. For $1.25 they could watch the newest movies or big sporting events.

At its peak in 1954, there were 148 households in and around Palm Springs, California, signed up to the service. Eventually it was forced out of business by the movie studios, who were worried that it would take away theater audiences.

Ridenour coauthored the patent on the company’s video scrambling technology. Obviously, a system to encrypt and decrypt signals could have other uses, such as scrambling the pictures that would be sent back to ground from U-2 spy plane missions.

International Telemeter was a hotbed of creativity. Ridenour and three of his colleagues created an early version of the compact disc—an optical storage disc that could store thirty million bits of data by spinning at twenty-four hundred revolutions per minute.

The company was also working on government projects, however. Alongside the assorted TV technologies it was developing, International Telemeter was also contracted to build a computer memory for Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Riverside, Ohio.

Ridenour was involved in America’s missile program from the start. In addition to being chief scientist to the air force, he was also the scientific adviser to the Ballistic Research Laboratories in Aberdeen, Maryland.

If President Eisenhower thought the missile program was off track, it was on Ridenour’s head—at least in part.

Shortly after the U-2 spy plane was commissioned, Ridenour took a more hands-on role in the Cold War arms race. He was hired by Lockheed to join its newly created Missile Systems Division. Within weeks of Ridenour’s arrival, a large proportion of Lockheed’s scientific staff quit to form their own business. Aeroneutronics, the business they created, would go on to work on large contracts related to the US space program.

After this mass walk-out—referred to in Lockheed as the “Revolt of the Doctors”—Ridenour was appointed chief scientist at Lockheed Missile Systems. One of his first jobs was to oversee the transfer of the lab from an existing facility in Van Nuys, California, to a new state-of-the-art operation in Palo Alto. It was one of the first commercial research facilities in the area, just a stone’s throw away from Stanford University. Lockheed’s lab helped to create the foundations of Silicon Valley; the research labs of the modern-day Lockheed Martin are still there today, across the road from the headquarters of Hewlett-Packard.

Once the lab was set up, there was no excuse for not building the perfect missile. Ridenour firmly believed that the reason to build the best missile was to ensure that you would never have to use it. Mutually assured destruction was a solid theory, he believed. He liked to game the Russians, teasing them with bits of technology and throwing a few misleading ideas into the public domain just to keep them on their toes.

“A genuinely secret weapon is absolutely useless in peacetime,” Ridenour told Popular Science magazine in May 1957. “Not all secrets need to be exposed, and they can be mixed in with a few lies. When a potential enemy can verify some ‘secret weapons,’ but not all, they will have to be very cautious.”

Ridenour had been dropping hints about his idea of the ultimate bomb since the tail end of World War II. Shortly after Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been destroyed (with bombs guided by Ridenour’s radar device), he wrote a darkly satirical one-act play, Pilot Lights of the Apocalypse, about the accidental destruction of the world. It was published in Fortune magazine—and then syndicated to newspapers across America.

The play is set one hundred feet underground in a “western defense command” center somewhere near San Francisco. It tells the story of two sergeants who inadvertently cause global nuclear apocalypse by mistaking an earthquake for an enemy attack—which their handbook suggests must have originated from a Danish satellite bomb. The reasoning was that Denmark had the highest negativity rating, due to local protests over a statue that had been gifted from the US President to the Danish King.

It is astonishing to think that such a biting polemic against the dangers of the nuclear bomb could have come from the pen of someone with a hand in its design and possible deployment. That Ridenour was kept in the military fold in spite of this public attack is even more extraordinary.

Yet the satellite bombs that Ridenour predicted in his satire were more than just science fiction. By the time Ridenour arrived at Lockheed, Wernher von Braun had been working on such a theory for years. Launching missiles from a satellite attack platform was one of the ultimate goals of what he was trying to achieve. As far back as 1946 Braun had warned the US Army that the “nation that first reaches this goal possesses an overwhelming military superiority over other nations.”

In an article for Collier’s magazine in 1952 Braun had stressed again the peril in allowing the communists to dominate space with manned space platforms full to the brim with nuclear weapons. He also outlined how the United States could build a circular space station orbiting Earth that could be used as a launchpad for manned missions into deep space. The editor’s comment in Collier’s read, “What Are We Waiting For?”

Walt Disney subsequently made a TV show about space exploration, extrapolated from Braun’s article.

With the Cold War at its peak, no ideas were off the table. Ridenour wanted Buck’s help to get some of those ideas off the ground—quite literally.