GOOD NEWS RACED through the ranks at Fee-Ask.

Word that Captain Baker had spotted survivors in the jungle near the Shangri-La Valley sent Colonel Elsmore and his Hollandia staff into high gear. Baker had only seen three khaki-clad people in the clearing, but his B-17 was only over the area for a few minutes, flying at high altitude. He couldn’t communicate with the people he saw, and he didn’t spot any wreckage. There was room for optimism. If three were alive, why not all twenty-four?

Maybe Colonel Prossen had somehow been able to set down the Gremlin Special intact in an emergency landing. Maybe the three survivors that Baker saw were an advance party, and others who’d been aboard the C-47 were hurt but alive at the crash site. Or maybe they’d split up, as the Flying Dutchman survivors had done, with some heading in another direction in search of help.

Those hopes found expression in material form. Elsmore’s team assembled what one observer called “enough equipment to stock a small country store.” Supply crews attached cargo parachutes to crates filled with essentials such as ten-in-one food rations, blankets, tents, first-aid kits, two-way radios, batteries, and shoes. Having spotted what looked like a WAC on the ground, they included less conventional jungle survival necessities including lipstick and bobby pins. Not knowing how many among the crew and passengers had survived, the would-be rescuers assembled enough provisions to feed, clothe, and temporarily house all twenty-four.

Excitement aside, Elsmore and his command staff knew they faced a serious problem: They had no idea how to reach the survivors, and worse, they had no idea how to get them back to Hollandia. If there’d been a way to land a plane in Shangri-La and take off again, Elsmore almost certainly would have done so already. He probably would have brought reporters along, to record him subduing or befriending the natives, possibly both, perhaps while planting a flag with his family crest to claim the valley as his sovereign territory.

Dutch and Australian authorities, who’d been in contact with Elsmore throughout the search, offered help and expertise outfitting an overland trek. But that idea was nixed when it became apparent that such an expedition would require scores of native bearers and an undetermined number of troops to defend against hostile tribes and thousands of Japanese soldiers hiding in the jungles between Hollandia and the survivors. Even more problematic than the cost in manpower and equipment, it might take weeks for marchers to reach the valley, and by then any survivors might be dead from their injuries or at the hands of natives or enemy troops. Even if the crash victims survived the wait, they might lack the strength for a month-long march over mountains and through jungles and swamps back to Hollandia.

Helicopters were raised as a possibility, but were almost as quickly shot down. As far as the Fee-Ask planners knew, helicopters wouldn’t be able to fly at the necessary altitudes—the air was too thin for their blades to generate the necessary lift to carry them over the Oranje Mountains.

Still under consideration were rescue pilots from the U.S. Navy who could land a seaplane on the Baliem River. Also on the drawing board were plans worthy of Jules Verne involving lightweight planes, blimps, gliders, and U.S. Navy PT boats that could operate in shallow water and might reach the interior by river. If a submarine had been available or remotely feasible, someone on Elsmore’s team no doubt would have suggested that, too.

But every idea had logistical flaws, some worse than others, so a rescue plan would have to wait. Elsmore’s immediate concern was getting the survivors help on the ground. Presumably some were wounded, so they needed medical care. Equally urgent, considering the stories about the natives, the survivors needed protection. One solution would be to drop in a team of heavily armed paratroopers, soldiers as well as medics, who wouldn’t mind—or at least wouldn’t fear—being horribly outnumbered by presumably cannibalistic native “savages.”

One challenge would be finding volunteers for such a mission. A bigger problem would be availability. Infantry-trained paratroopers were in the thick of the fight. As far as Elsmore and his staff knew, none were anywhere near Hollandia.

The Southwest Pacific region hosted two storied airborne units, the 503rd and the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiments. Both had played major roles in the Pacific war, most notably and heroically in the Philippines. Three months earlier, in February 1945, the 503rd had recaptured the island of Corregidor and helped General MacArthur make good on his promise to return to the Philippines. That same month, on the island of Luzon, the 511th had carried out a lightning raid twenty-four miles behind enemy lines that freed more than two thousand American and Allied civilians, including men, women, and children, from the Los Banos Internment Camp.

Both airborne regiments were still committed to combat in the Philippines, and winning the war took precedence over fetching a handful of survivors from a sightseeing crash in the New Guinea jungle.

When it looked as though they’d run out of paratrooper options, an idea struck one of Elsmore’s planners, a bright young officer named John Babcock.

Before the war, Babcock taught biology and chaired the science department at a private military high school in Los Angeles. When the United States entered the war in December 1941, he traded his chalk for the rank of lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army. His science background led to his assignment as Fee-Ask’s chemical warfare officer.

A few weeks before the crash, Babcock learned that one of his former students was based in Hollandia. Babcock knew two things about this particular young man: C. Earl Walter Jr. First, he’d been expelled from school as a troublemaker, and second, he was now an infantry-trained paratrooper, frustrated about being stuck in Hollandia.

C. EARL WALTER Jr.’s boyhood revolved around his father, C. Earl Walter Sr.

Most of that boyhood was spent in the Philippines, where the elder Walter had moved his wife and toddler son from Oregon to take a job as a lumber company executive. Before the boy was nine, his mother fell ill with malaria. She returned to the United States for treatment, but she so missed her husband and son that she took the next boat back to the Philippines. She died several months later.

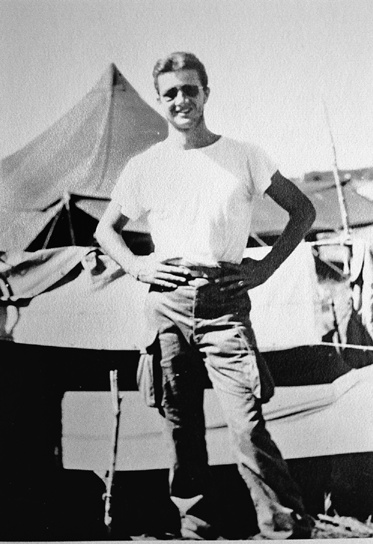

Captain C. Earl Walter Jr. (Photo courtesy of C. Earl Walter Jr.)

That left just C. Earl Walter, senior and junior. Neither cared for the name Cecil, so both went by Earl. In the midst of the Depression, father and son lived on the southern Philippines island of Mindanao, in a big house with a full-time cook and a couple of native houseboys who saw to their every need. The younger Earl Walter had a small horse and his own little boat, and lots of friends who lived in the barrio near his home. He was smart, but with so many distractions and a busy father, school was a low priority. So low, in fact, that for two years Earl Junior didn’t attend. He preferred to go with his father into the wild reaches of the island on lumber surveying trips. His favorite boyhood memory came from one of those trips.

“We had been hiking all day, and we found this little glade in the forest, and there was a little creek that had formed a pool,” Walter recalled. “So he and I took our clothes off and we got in the water and splashed around just to get rid of the sweat. We were both naked, and when we got out of the water, it was so funny because the natives were standing two or three deep around the pool. Dad asked our guide what that was all about, and he said, ‘They’re just curious to see if you’re white all over.’ ”

By the time he was fourteen, the tall, handsome white boy with wavy brown hair, blue-gray eyes, and a well-off father was even more of a curiosity, especially among the local girls. And vice versa. “At that age you’re old enough to wonder about women,” Walter explained. “You wonder what it’s like.”

Walter’s father saw where things were headed, and he didn’t like the direction. Above all, he worried that his only child wasn’t getting much of an education. He had remarried after his wife’s death. His new wife’s mother, who lived in Portland, Oregon, was willing to take charge of Earl Junior. Among other benefits, the move would give the boy a chance to catch up to his American peers in school. It’s possible that Earl Senior had other concerns, too. Even before Pearl Harbor, the elder Walter feared a Japanese invasion. “When I was growing up with Dad, he used to say, ‘I’m going to put a machine gun over there, and a machine gun over there, and when the Japs come, we’ll be ready for them.’ ”

Earl Junior returned to the States, first to his stepgrandmother’s house and then to the care of his paternal grandmother, who did her best to spoil him. His father decided that a firmer hand was needed: “I think Dad felt that I needed a military school to go to, and that might straighten me out.”

Earl Junior shipped out to the Black-Foxe Military Institute in Los Angeles, a high-toned private academy complete with a polo team. Located between the Wilshire Country Club and the Los Angeles Tennis Club, Black-Foxe provided a useful place for movie stars to stash their wayward sons. At various times, the Black-Foxe student body boasted the sons of Buster Keaton, Bing Crosby, Bette Davis, and Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin’s son Sydney once described Black-Foxe as “a sleep-away school for the sons of Hollywood rich people.”

There, Earl Junior grew into his full height of six-foot-four and became an All-American swimmer, backstroking his way onto a record-setting relay team. One class he especially liked was biology, which meant that he skipped it less often than the others. His biology teacher was a future U.S. Army lieutenant colonel named John Babcock.

For the most part, Earl Senior’s get-tough plan backfired. Earl Junior wasn’t a malicious teen, but he found endless ways to avoid studying: “It didn’t straighten me out. In fact, I learned more bad habits there than I did anywhere.”

His stepmother had made the mistake of setting up a generous allowance to ease the transition into a new school. Black-Foxe administrators controlled the money, but Earl found a clever way around that barrier. Drawing on his school account, he spent lavishly at the school store on notebooks and other supplies. Then he’d sell them for half price to other students, for the cash. Even with the discounts, “I had more money than I knew what to do with.”

“What kind of trouble did I get into? Well, I was always looking for female companionship,” the younger Earl Walter recalled. “I had a bosom buddy named Miller, and we’d go to downtown Los Angeles, just hitchhike down to the bars. If you had money in those days and you were tall enough, they served you liquor. So I’d always have a couple of gin drinks. There was one area of L.A. where the burlesque shows were. Miller and I liked to look at naked women, so that’s where we’d go.”

Black-Foxe decreed that young Earl was a “bad influence” on the other boys and kicked him out. He returned to his grandmother’s house and finished high school in Portland. By then he was nearly twenty. “I heard that quite a few parents told their girls to stay away from Earl Walter because, what the hell, I was old enough to chase women and liked it.”

One girl he dated introduced him to her friend Sally Holden. Her mother wasn’t keen on Earl, but Sally was. “She was a beautiful gal,” he said, “and we mutually fell in love. Once we started going steady, I had no interest in anybody else.”

EARL SPENT TWO semesters at the University of Oregon before being drafted in August 1942, when he was twenty-one. He went to officer candidate school and underwent parachute training at Fort Benning, Georgia. Just before he was about to ship out for the European front, as a junior officer in the infantry, Army Lieutenant C. Earl Walter Jr. received unexpected news about his father. The last he’d heard from Earl Senior was a letter in 1941, just before Pearl Harbor, in which his father wrote that he’d “most likely stay on in the islands in the event that war came.”

As a U.S. territory, the Philippines sent a resident commissioner to Washington to represent its interests, without a vote, in Congress. At the time, the resident commissioner was Joaquin Miguel “Mike” Elizalde, a member of one of the Philippines’ richest families. The Elizaldes held an interest in the lumber company where the elder Earl Walter was an executive. Mike Elizalde learned that Earl Senior had followed through on his plan to remain in the Philippines when war came. Rather than surrender and face internment or death, or try to flee to Australia or the United States, Earl Senior took to the jungles of Mindanao. There he led a resistance force of Filipino guerrilla fighters. Earl Senior’s bravery earned him praise, medals, and the rank of major in the U.S. Army, on his way to being commissioned a lieutenant colonel.

A book about a fellow guerrilla leader in the Philippines described the elder Walter as a “tough, no-nonsense warrior” and “a leathery man in his fifties . . . ready with his fists.” It said he’d been honored for bravery under fire in World War I and picked up where he left off during World War II. Walter and his guerrilla troops “mounted as vicious a close-in infantry action as men have fought”—ambushing Japanese soldiers along a coastal road and patrolling the streets of Japanese garrison towns at night.

Mike Elizalde, the Philippines’ resident commissioner in Washington, sent word to the younger Walter to let him know that his father was alive, well, and fighting the Japanese. Walter told one of his commanding officers at the time that Elizalde “gave me enough information of my father to at least stop my fears for his safety and make me proud of his work.”

C. Earl Walter, Senior and Junior. (Photo courtesy of C. Earl Walter Jr.)

The news about his father had another effect: C. Earl Walter Jr. lost interest in battling Germans and Italians in Europe. In a report filed at the time, a lieutenant colonel quoted Walter as saying that he didn’t know many specifics of his father’s guerrilla fighting, but it was “enough to make me envy the type of work he was doing.”

With help from Elizalde, Lieutenant Walter volunteered for a special commando and intelligence unit, the 5217th Reconnaissance Battalion, made up almost entirely of Filipino-American volunteers. The idea was to insert Filipino-American soldiers onto one of the Japanese-held islands by submarine or parachute, under the theory that they could immediately blend in among the native civilians. Once there, members of the unit would organize guerrilla operations and direct supply drops for resistance fighters. That sounded ideal to C. Earl Walter Jr.

Having grown up in the Philippines, Walter knew the culture and the Visayan dialect, which made him an ideal officer for the 5217th. As a qualified paratrooper, he was a natural to establish a jump school for the battalion outside Brisbane, Australia, known as Camp X. Best of all, when he got to the Philippines, he could fight alongside his father. That was the plan, at least.

After marrying Sally, Walter shipped out in early 1944 and got to work turning members of the 5217th Recon into qualified paratroopers—occasionally with amusing results. The U.S. Army used large parachutes, and many of the Filipino-American soldiers weighed less than a hundred and twenty pounds. After jumping, they’d float around in the air currents. “This one little guy kept yelling, ‘Lieutenant, I’m not coming down!’ ” Eventually he did, and afterward one of Walter’s sergeants fitted smaller men with weighted ammunition belts to speed their descent.

In July 1944, upon his arrival in the South Pacific, Walter filled out a duty questionnaire for officers. He immediately sought a “special mission” in the Philippines prior to the anticipated Allied invasion. He explained his reasoning more fully in a long, bold memo to his new commanding officer. In it, he detailed his upbringing in the Philippines and his knowledge of the islands and its languages, and described his father’s work and his own ambitions. “In short,” he wrote, “I have an intense hatred for the Jap and came to this theater hoping to join a combat parachute unit and do my bit in their extermination.”

Later in the memo, Walter wrote that he would perform to the best of his ability in a noncombat intelligence or propaganda mission, but only if he were denied a posting in the heart of the action. Though he had yet to fire a shot in anger, Walter believed he knew how he would react if and when the opportunity arose. Despite his discipline and training, Walter wrote, he might not be able to restrain his trigger finger in a noncombat assignment. “My only desire is that I be given a job which would involve possible contact with the enemy, as I am afraid my liking for combat with the Jap might run away with itself when it should be curbed.”

His thirst for battle notwithstanding, Walter’s unit was left out of the invasion of the Philippines and MacArthur’s return to the islands in October 1944, which came some three months after Walter had appealed for a role in the fight. Even as the battle for control of the Philippines continued, Walter and his men remained at ease. Ill at ease would be more accurate.

While suppressing his frustration and biding his time for a meaningful assignment, Walter worked with members of the battalion who were secretly brought to the islands by submarine for intelligence missions. One submarine trip was to the island of Mindanao, and Walter went along. When he arrived at the landing place, he climbed out of the sub to find a surprise: his father was waiting there to greet him. Walter was thrilled—he hadn’t seen Earl Senior for seven years, since he’d been sent to the United States to finish high school far from the Filipinas.

But his happiness was short-lived. The elder Walter told his son that he didn’t want him taking part in more secret missions, by submarine or any other conveyance. Earl Senior also said that he intended to let higher-ups in the U.S. Army know his wishes. As far as C. Earl Walter Sr. was concerned, the Allies would have to win the war without the help of C. Earl Walter Jr.