AFTER EVERY PARATROOPER in the 1st Recon volunteered to jump into Shangri-La despite the dire warnings, Captain Earl Walter chose ten of his troops. He immediately picked his right-hand man, Master Sergeant Santiago “Sandy” Abrenica, whom Walter considered a good friend and the best soldier he’d ever met. Abrenica was thirty-six, whippet-thin, with dark, deep-set eyes and a wary expression. Born on Luzon in the Philippines, Abrenica immigrated alone to the United States in 1926, when he was seventeen, declaring that his intended address was a YMCA in Seattle. As a civilian he’d worked as a gardener, and as a hobby he raced model airplanes.

Next Walter needed two medics who he thought might have the toughest job of all. They’d be parachuting into a dense jungle to treat the survivors, while the rest of the unit jumped into a flat, mostly treeless area of the Shangri-La Valley some thirty miles away to establish a base camp. After talking to his men and leafing through their service records, he picked Sergeant Benjamin “Doc” Bulatao and Corporal Camilo “Rammy” Ramirez. Both Doc and Rammy were good-natured, with easy smiles—Rammy’s was more distinctive, as it revealed two front teeth made of gold. Otherwise they were entirely different. Doc Bulatao was quiet, shy almost, while Rammy Ramirez had the gift of gab and an outsize personality for a man who stood just five-foot-one.

Like Abrenica and most other enlisted men in the 1st Recon, the thirty-one-year-old Bulatao was single and had immigrated to the United States as a young man. A farm worker before the war, Bulatao joined the 1st Filipino Regiment in California before being assigned to Walter’s unit.

Rammy Ramirez’s route to Hollandia was more circuitous and more perilous. Born in the city of Ormoc on the island of Leyte, Ramirez enlisted ten months before the war. He was assigned to the Philippine Scouts, a unit of the U.S. Army consisting of native Filipinos who served in the islands under American command. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines after Pearl Harbor, Ramirez was part of the overmatched, undersupplied force that held out against the enemy, hunger, and dysentery for more than four months on the Bataan Peninsula. After Filipino and American troops surrendered in April 1942, Ramirez endured the Bataan Death March, suffering not only from his captors’ brutality and the lack of food and water but also from malaria and dengue fever. Only a daring gambit spared him from a prisoner-of-war camp.

At a temporary holding area, Ramirez noticed a hole at a corner of a fence that had been patched with barbed wire. “I said to myself, ‘I will get through there,’ ” he recalled. The next night, he waited until a Japanese guard set down his rifle and appeared to doze off at his post. “So I roll, little by little, towards the gap in the barbed wire.” He tried to pry apart the patch to enlarge the opening but couldn’t find the strength—“It’s kind of hard, because I am small, you know.” As he crawled through, his shirt snagged; razor wire ripped a gash in his side.

“About ten feet from the barbed wire were bushes, lots of bushes and trees. So I went toward the bushes when I got out. I didn’t even notice that I cut myself.” He was about a hundred and fifty yards from the fence, running through the woods, when he heard gunfire behind him—“boom, boom, boom, boom, boom!” Later Ramirez learned that Japanese guards had opened fire when other prisoners tried to follow him through the hole. “I kept running, and my head was really pounding—the fever, malaria fever and dengue fever mixed.”

Ramirez dragged himself to a nearby house, where sympathetic residents gave him clothes to replace his uniform. He hid his dog tags in his shoe, avoided main roads, and headed toward Manila, an “open city,” supposedly safe from bombing by either side. He saw an ambulance and hitched a ride to a hospital, but everyone there was evacuating to a medical ship bound for Australia. Manila was blacked out, but he found his way to the pier and saw the ship silhouetted in the moonlight. He talked his way on board and curled up in a warm spot on the deck amid scores of sick and wounded.

After a month recovering in a Sydney hospital, Ramirez regained his strength just as the 1st Filipino Regiment was arriving in Australia. He was still officially attached to the U.S. military, so it seemed a natural fit. “They discharged me from the hospital and put me with them.”

In time, he was assigned to medical, commando, and paratrooper training in Brisbane as part of the 5217th Reconnaissance Battalion, the predecessor to the 1st Recon, under the command of Captain Walter. Now twenty-six, with a scar for life from his escape, Rammy Ramirez wanted to help Margaret, McCollom, and Decker to make their own getaway.

Walter was especially glad to have Ramirez on the team. “I just liked his gung-ho attitude. He was happy.” Other medics, including Bulatao, were more experienced treating patients, “but they weren’t as free and easygoing as Rammy was. I felt the two survivors that were badly injured . . . needed someone that was kind of happy and a good talker, and was not the least bit hesitant about talking back and forth.”

“That’s how I picked those two for the jump,” Walter said. “I picked ’em mainly because Ben was the most qualified and Rammy had the most guts.”

After Abrenica, Bulatao, and Ramirez, Walter filled out his parachute infantry team with seven of his most senior and capable enlisted men: six sergeants—Alfred Baylon, Hermenegildo Caoili, Fernando Dongallo, Juan “Johnny” Javonillo, Don Ruiz, and Roque Velasco—and a corporal, Custodio Alerta.

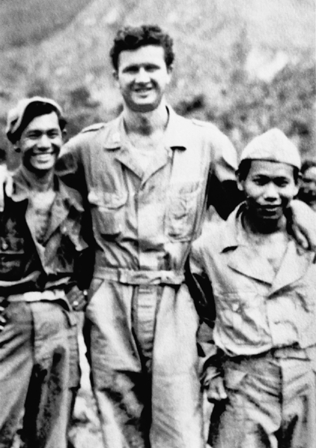

Captain C. Earl Walter Jr. with Corporal Camilo “Rammy” Ramirez (left) and Sergeant Benjamin “Doc” Bulatao. (Photo courtesy of C. Earl Walter Jr.)

In civilian life, they’d been gardeners and kitchen workers, farmhands and laborers, familiar with the slights and discrimination routinely experienced by Filipinos in America. Now they were U.S. soldiers, volunteering to parachute into uncharted territory to protect and rescue three comrades. When Walter was choosing his squad, neither he nor his men knew that the first natives who made contact with the survivors were friendly. All they knew were Walter’s warnings: no maps, no safe drop zone, no predicting the natives’ response, and no exit plan. Yet all they wanted to know was how soon they could jump into Shangri-La.

Walter spoke again with Colonel Elsmore and Colonel T. R. Lynch, deputy commander of Fee-Ask, who was deeply involved in the search and rescue effort. In an earlier meeting, Lynch made clear to Walter that he’d be given wide latitude in terms of choosing which men to use and how best to carry out the mission. Walter quoted Lynch as saying, “It’s gonna be your operation. You’re entirely responsible.” Walter understood Lynch to mean that if it went horribly wrong, if a live WAC, a live lieutenant, or a live sergeant came back dead, or if his ten paratroopers failed in any way, Walter would shoulder the blame. His answer: Bahala na.

After meeting with the brass, Walter joined a flight crew for several reconnaissance passes over the valley, the crash site, and the survivors’ clearing. Then he spoke again with his superiors. “We figured out just how they were going to get us in there,” Walter recalled. “I was very concerned because I knew we had to parachute in there. It was the only way. The territory north of the valley was inhabited by headhunters, we figured, and south of the valley were Japanese troops. So there’s no way to get in there by foot unless you wanted to get into a firefight, and I wasn’t the least bit interested in exposing us to that.”

Walter instructed his men to pack supplies and parachutes. None of them had jumped since leaving their training base in Brisbane months earlier, so he arranged for each to make one or two practice jumps in Hollandia. “That was a mess because the only place they found that we could use was kind of a swampy area,” Walter said. “The men and I laughed about it afterward, but we sure as hell didn’t at the time. We were in what they called kunai grass”—with sharp edges, each blade several feet high. “It was very thick and almost one hundred percent coverage. We’d take two or three steps and then purposely fall forward to make an indent in the grass, and then we’d take two or three steps and fall again. A mess.”

Walter went back to his medics and asked, “Do you really want to do this?”

“I remember both of them saying, ‘Yes, sir. We want to do this because they need us.’ ”

“I know they do,” Walter told his men. “I can’t do it. You can, because you know what to do medically.”

Later, Walter said of the moment: “This, to me, is one of the things I want people to think about. They didn’t have to do this. They wanted to.”

Walter noted in a journal that it was his twenty-fourth birthday, Friday, May 18, 1945. Having finally found himself engaged in a real mission, he was too busy and too distracted to celebrate. After his last practice jump, he returned to camp, packed parachutes, and went to bed.

ON THEIR SIXTH day in Shangri-La, the survivors spent the morning waiting for the comforting sound of the approaching supply plane. When the 311 appeared, the sky filled with parachutes slowing the descent of wooden crates. When the survivors made contact with the plane’s crew by walkie-talkie, they warned that however bad the terrain looked from the sky, it was even worse on the ground.

In her diary, Margaret wrote that she told the crew: “Don’t let anyone jump in here if it means he’ll be killed. I’d rather die right here than have anyone killed trying to get me out.” McCollom and Decker felt the same. “We had seen enough of death and tragedy,” she wrote. “God knows we wanted to live, but not at the expense of someone else.”

Their fears for the paratroopers would remain with them for at least another day. The mist rolled in early, shrouding the jungle and the surrounding ridges. That made it impossible to fly safely over them, much less jump into the cloudy mess.

When the plane was out of sight, McCollom traipsed into the jungle in search of cargo. “I could no longer move at all,” Margaret wrote, “and Decker was so white and feverish that McCollom sternly ordered him to stay in camp. Flesh had melted away from all of us, even McCollom.”

On successive trips, McCollom brought back a package filled with pants and shirts, but only in a size small enough to fit Margaret. She was grateful, though she wished he’d also found panties and bras to replace the underwear she’d removed five days earlier to make bandages. On another outing, he found enough thick blankets to fashion two makeshift beds in their jungle infirmary. He made one for Margaret and the other for him and Decker to share. That night, fleas in the blankets tormented Decker but ignored McCollom, which annoyed Decker even more.

Returning to their knoll after another trip, McCollom shouted, “Eureka! We eat!” In his arms were boxes of ten-in-one rations.

“Food, real food, at last, after almost six days,” Margaret wrote. She confessed that her stomach ached from hunger, and the men admitted the same despite having gorged on the tomatoes without her. As McCollom pried open the packages, Margaret’s spirits soared: “It was such a beautiful sight: sliced bacon in cans, canned ham and eggs, canned bacon and eggs, canned meat, canned hash and stews, the makings of coffee, tea, cocoa, lemonade and orangeade, butter, sugar, salt, canned milk, cigarettes, matches, and even candy bars for dessert.”

All three chose cans of bacon and ham, and each hastily worked little key openers to reveal the tasty-under-the-circumstances innards. As they dug into their cold breakfasts, the survivors gave no thought to making a fire. For one thing, all the nearby wood was saturated from the relentless rains. “Even more important,” Margaret wrote, “even McCollom was too far gone physically to do anything that took an extra, added effort.”

Despite how hungry she’d been, Margaret felt stuffed after only a few bites. She stopped eating before she’d finished one small can, realizing that a steady diet of Charms, water, and a few mouthfuls of tomatoes had shrunk her already small stomach.

As they waited for the medics, the survivors’ anxiety grew about Margaret’s and Decker’s injuries. The ointments and gauze they’d found in the supply crates had done nothing to slow the spread or the flesh-killing power of gangrene. After they ate, McCollom did what he could to tend to their wounds. He removed the dressings on Margaret’s legs, releasing the nauseating stench of infection. McCollom tried to ease off the bandages, but they were stuck to the burned skin. He closed his eyes, knowing the pain he’d have to cause Margaret by ripping them off.

“Honest, Maggie, this hurts me worse than it does you,” he told her.

Within an hour the fresh bandages he’d applied were drenched with foul-smelling pus. They repeated the excruciating process. Margaret wrote: “I tried not to show my growing terror that I would lose both legs, but it was mounting in me like a tide, and sometimes I thought I would pass out with fear.”

Margaret’s fears deepened when she tried to help McCollom treat Decker. The gangrene on his legs and backside had grown worse during the previous twelve hours. “He was in great pain and we knew it, although he had never said a word,” she wrote. “He lay on his stomach all day with a kind of exhausted patience and pain.”

In the afternoon, the native leader they called Pete returned with his greatest show of trust yet: a woman whom Margaret took to be his wife. The couple stood on the knoll across from the survivors’ camp and beckoned them over. Neither Margaret nor Decker could walk, so McCollom went alone. The two leaders shook hands and tried to communicate, with little success. At breaks where a response seemed appropriate, McCollom murmured, “Uhn, uhn, uhn,” just as he’d heard the natives do when the two groups met. The conversation didn’t progress much beyond that.

Elsewhere in her diary, Margaret wrote of the natives: “They would chatter like magpies to us. We would always listen carefully, from time to time muttering, ‘Uhn, uhn, uhn.’ They would be delighted, like the bore to whom you keep saying, ‘Yes, yes, yes’ during long-winded conversation. ‘Uhn, uhn, uhn,’ we would say as the natives chattered. They would beam at us and then talk twice as fast.”

As McCollom spoke with his counterpart, Margaret sized up the native woman. Margaret was pleased to find that the first woman she’d seen up close in Shangri-La was “shorter than my five-feet, one-and-one-half inches.” A woven bag hung down her back, suspended from a string handle draped over her head. She stood “mother naked,” other than what Margaret described as “a queer New Guinea g-string woven of supple twigs” that somehow remained in place on her hips.

Unknown to Margaret, the woman’s name was Gilelek. Despite the practice of polygamy that would have allowed Pete/Wimayuk Wandik to take more than one wife, she was his one and only.

“She and all her jungle sisters under the skin were the most graceful, fleet creatures any of us have ever seen,” Margaret wrote. “And they were shy as does.”

THE COUPLE LEFT, and in the late afternoon the survivors settled into their blanket beds. Less than an hour later, Wimayuk and a large group of his followers returned. It appeared as though his wife had approved of the strangers, and had reminded him that his obligation to guests went beyond kindness.

“They held out a pig, sweet potatoes and some little green bananas, the only fruit we ever saw,” Margaret wrote.

“They want to give us a banquet,” McCollom said. “Maggie, if our lives depend upon it, I cannot get up and make merry with the natives.”

“Amen,” said Decker.

If the feast had been offered a day earlier, the survivors would have been thrilled. “But tonight,” Margaret wrote, “for the first time in days, our stomachs were full of Army rations, and we were bushed.” They used sign language to explain as politely as possible that they were too tired, too sick, and too full to appreciate another meal.

By declining the dinner, Margaret, McCollom, and Decker had effectively canceled what would have been the first Thanksgiving in Shangri-La. The man they called Pete would have filled the role of Chief Massassoit, and the survivors would have played the Pilgrims.

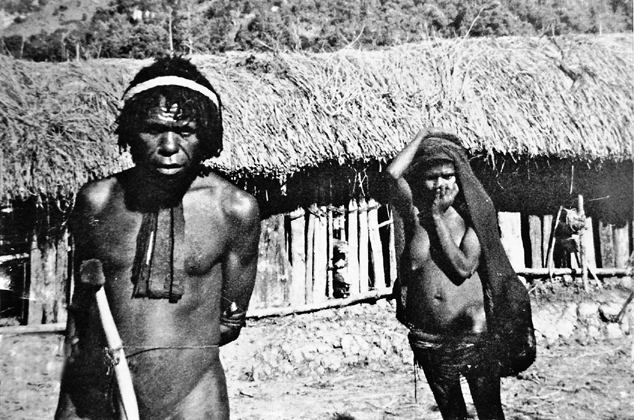

A native couple in a Dani village, photographed in 1945. (Photo courtesy of C. Earl Walter Jr.)

More significant, they unknowingly missed a chance to become bonded to the natives through one of the tribe’s most important community rituals: a pig feast. As an anthropologist later explained: “It is the remembrance of pigs which holds . . . [this] society together. At every major ceremony pigs are given from one person to another, and then killed and eaten. But they leave behind memory traces of obligations which will be paid back later; when this happens, the people will create new obligations. And so the network of the society is constantly refurbished by the passage of pigs. A single man in his lifetime is bound to his fellows by the ties of hundreds and perhaps thousands of pigs which he and his people have exchanged with others and their people.”

Despite the deep symbolism of their offer, the natives took no apparent offense at the survivors’ refusal to share a pig.

“Pete, who must have had a wonderfully understanding heart in that wiry black body, comprehended at once,” Margaret wrote. “He tucked the pig more firmly under his arm. He ordered his men, who had started a fire by some magic known only to them, to put it out. Then he clucked over us reassuringly and herded his followers home.”

The survivors burrowed into their beds and went to sleep, feeling sated and relatively warm and comfortable for the first time since leaving Hollandia. In what Margaret called “the irony of an evil fate,” they were awakened several hours later by a sudden cloudburst. Margaret’s nest of blankets, arranged on low ground, became a woolly swamp. The bed on higher ground shared by McCollom and Decker was wet, but not soaked. Margaret ordered them to make room, and she crawled in alongside them.

“Lord,” said McCollom in mock protest, “are we never to get rid of this woman?”

They huddled together against the cold and wet through the night, talking now and again under the blankets about helicopters, medics, and being rescued.