5

Legends

***

A six-hour session

Australia ‘A’ was practising in Edinburgh when stand-in coach Allan Border exploded, asking both the batsmen and bowlers why they weren’t working harder and longer.

The Test legend went into overdrive talking about commitment and how bowlers needed to bowl longer spells and batsmen needed to work at batting all day, rather than in just ten and fifteen-minute stints.

Mike Hussey took it to heart and back in Perth, on a rare early season Saturday off, teamed up with his coach Ian Kevan and batted three two-hour sessions against the bowling machine, stopping only for forty minutes for lunch and twenty minutes for tea.

It was ball after ball after ball. Never had he been more exhausted. Or more satisfied.

***

To the point

Coming off the Adelaide Oval after his enchanting Ashes century on debut, Mark Waugh said, ‘I should have been playing [Tests] for years.’

***

How sweet it is

Approaching the high-stakes clash at the Junction Oval between heavyweight Premier clubs, Melbourne and St Kilda, headliner Dean Jones had been spruiking all week how he intended to hit Shane Warne so hard and high it would end up way down south back at his mansion in Brighton.

On Jones’s arrival, St Kilda’s captain Jason Jacoby introduced Warne from the city end and quipped, ‘Mate, it’s going to be pretty hard to hit him back into Brighton from this end!’

Deano turned around and said, ‘Jacko, if there’s one player in the world though who could do it, it’s me!’

Within minutes, aiming for Albert Park Lake, he charged Warne’s signature leg break, missed and was stumped by yards.

‘It was a sweet, sweet wicket,’ said Jacoby.

***

It was the day the ’89 Ashes squad was due to be announced and Merv Hughes was on tenterhooks, wondering, wishing and hoping he was going to be a part of the touring XVII for the first time.

He and several of the other leading Australian aspirants were at Sale for a promotional game and on the way had agreed to visit a local hospital to cheer up the patients.

Television cameramen duly followed them from room to room … with the team announcement imminent, they were ready for every reaction.

The good news finally arrived. Hughes and his Victorian mate Dean Jones were both ‘in’. High-five time. Had he been able to complete a cartwheel, big Merv would have done one, then another. He was ecstatic.

Wanting to be alone just for a moment, he slipped into a side room and closed the door behind him and yelled at the top of his voice, ‘YOU %#*&IN’ BEAUTEEE!!’

There was a gasp and two old ladies sat bolt upright in their beds. ‘Is everything all right young man?’ asked one.

‘Yes,’ said Merv, ‘… and sorry about that, girls. I’ve just been chosen for the Ashes.’

‘Oh, you poor boy,’ they said.

***

Dean Jones was on his way to his epic double-century against the West Indies in Adelaide in 1988–89, both he and tailender Merv Hughes being treated to some serious ‘chin music’ from the West Indian pace battery.

‘Don’t worry mate,’ Merv kept on saying to Jones, ‘I’ll stick it out. Hang in. You’ll get your 200.’

Merv wasn’t as quick on his feet as Deano and kept on being pinged on his thigh, fingers, chest and finally a direct hit to the back of the neck. For a moment there he was seeing stars. Deano ambled down the wicket to offer his condolences. ‘Are you 200 yet?’ asked Merv.

One day at Headingley, Merv came in with express instructions to back an in-form Steve Waugh, get the 1s and get off strike. Soon into his innings he knocked Graham Gooch straight over the top for 6. Later, captain Allan Border asked him what was going on there?

‘Sorry skipper,’ said Merv. ‘I was playing carefully like you told me and I just followed through a bit too strong.’

***

A star is born

The roly-poly blond from Hampton approached St Kilda’s practice captain Noel Harbourd. It was the first day of pre-season at the Junction.

‘What’s yer name, son?’

‘Warne … Shane Warne.’

‘And waddaya do?’

‘Oh, I bat … and bowl a bit, too.’

The kid was sent down to the far net with the other fourth XI hopefuls, had a bat and sent down some leggies, some of which bit and spun markedly.

The club’s coach Shaun Graf drifted across to Harbourd and asked what the blond kid did.

Told he was basically a batsman, Graf said, ‘Not sure about his batting, but he can sure bowl.’

***

It was years before the true story emerged about Allan Lamb’s incredible 18-run last-over onslaught against Bruce Reid in Sydney in 1986–87 … it was much to do with cannabis cakes!

The night before Lamb’s matchwinning smites to snatch a glorious one-day victory for Mike Gatting’s touring Englishmen, he and David Gower co-hosted a party at a Bondi beach apartment. Some of Lamb’s mates had catered and mischievously sprinkled some little cupcakes with marijuana. Very tasty indeed, thought everyone, especially the party-loving Lambie who came back for seconds.

‘It was a cracking night,’ said Gower. ‘Fortunately, the game the next day was a day-nighter and we had plenty of time to recover …’

***

Truly electric

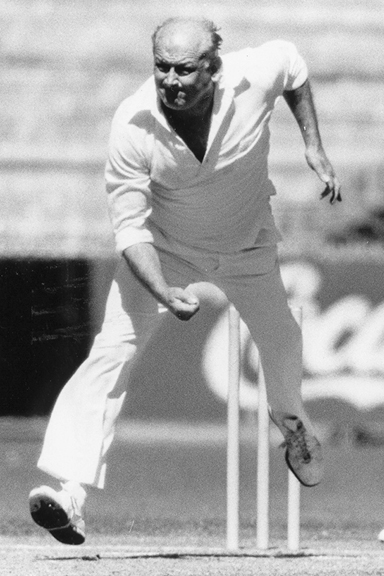

Other than Garry Sobers, no post-war all-rounder was as electric or as formidable as South African Mike Procter, whose Test career was cruelly restricted to just seven home Tests.

When South African cricket was plunged into isolation soon after the 1970 Australians had been humbled 4–0, Procter, Graeme Pollock and a young Barry Richards were among those denied a Test cricketing forum.

So dynamic did Procter become at English county level that many referred to his English club Gloucestershire as ‘Proctershire’. He amassed 1000 runs in a season nine times and took 100 wickets twice.

Teammate David Green said Procter ‘bowled at 100 miles per hour from extra cover off the wrong foot’. A circular whip of the arm and powerful shoulders were his keys to withering, discomforting pace. Like a Keith Miller, he could halve his run-up and be just as fast.

He walked tall in any cavalcade of champions.

***

Bless you Leo

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, I regularly visited the old Bodyliner Leo O’Brien at his home in Mordialloc for a chat and a cuppa. He’d be sitting out the back in his kitchen, in footy shorts and a singlet, listening to the races. I’d just become editor of Cricketer and was interested in starting a regular series of reminiscences from the personalities of yesteryear. One afternoon I asked Leo if he may be able to put in a good word for me to help me gain an interview with his mate Bill Ponsford.

‘Oh, Ken,’ he said, ‘Ponny is almost eighty now. He doesn’t talk to anybody much other than his family. Don’t think he would have given a media interview in twenty years.’

I rang Bill’s son Geoff and he said basically the same thing. ‘Dad is very happy that you are interested in his career Ken, but sorry, he doesn’t do interviews any more.’

The following Friday night, my phone rang and it was Geoff. ‘You could have knocked me down with a feather Ken, but Dad will see you. Can you come after work on Monday?’

That weekend I read and re-read everything I could find on the old record-breaker. He was the only man to twice make 400 in an innings. If D G Bradman hadn’t emerged, Ponny would have been the ultimate runmaking machine of the era.

Mr Ponsford smiled when he saw me but he was unbelievably shy. To my carefully typed twelve to thirteen questions he either said ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Desperate to ‘buy’ some time, I looked around the lounge-room of his son’s house and said, ‘Mr Ponsford, you have been one of Australia’s most outstanding cricketers and sportsmen … but there’s nothing here on display to show that… there is no memorabilia at all … no blazers, no stumps …’

There was a pause and Mr Ponsford finally said, ‘Stumps, Ken? Tomato stakes! And blazers – they’ve been keeping our puppies warm for years.’

We all laughed and Ponny began to chat amiably. An hour and a half later, I had my story and when we were finished my photographer John Hart took some lovely happy snaps outside with him holding ‘Big Bertha’, his famous old bat.

Twenty years on, I met Geoff Ponsford again – along with Bill Ponsford jnr – at the unveiling of the new Ponsford Stand at the MCG.

‘Good to see you,’ said Geoff. ‘We still remember that lovely interview you did with Dad. He really enjoyed himself … but you were lucky to get it you know …’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I still don’t know what changed his mind.’

‘It was Leo,’ he said, ‘your mate Leo O’Brien. He rang Dad every day for a week until Dad said yes!’

***

Unforgettable

Geoffrey Boycott the press-box model was far more entertaining than Geoff Boycott the former England No. 1.

He was delightfully disparaging, giving another tint to the BCC’s commentary, especially when he talked about how so-and-so wouldn’t get his grandmother out or how he’d play so-and-so with a stick of rhubarb.

His BBC commentary partner Jonathan Agnew took the new ball for England, albeit in just three Tests and as he delightfully reminded Geoffrey every now and again, one of his first-class victims ‘was actually you Geoffrey’.

‘No way,’ declared Geoffrey. ‘Out to you? No way … no.’

Aggers remembered all his big wickets and was certain he’d dismissed him in his first over of a championship match – and at Geoffrey’s own dunghill of Headingley.

‘No, no, no way … not you Aggers …’

‘But Geoffrey, it’s like a snapshot in my mind. First over, big crowd, all Yorkies, a perfect outswinger and you snicked it straight into the soft hands of Michael Haysman – G Boycott, c. Haysman, b. Agnew, 0.’

‘No, no, no,’ Geoffrey continued.

‘All right, let’s Google it.’

And there it was … clear proof: G Boycott, c. Haysman, b. Agnew, 9! Nine? When did he get those?

‘It’s still a famous wicket though for me,’ said Agnew, ‘and one I’ll never allow Geoffrey to forget.’

***

Letting ’em rip

Before iconic expressman Jeff Thomson smashed his shoulder in the chilling on-field collision with Alan Turner, his Australian teammates rated his pace at well above the old 100 miles per hour mark (over 160 kilometres per hour).

‘He was as far ahead of any other bowler for sheer speed as Don Bradman was ahead of all the others for runs,’ said one of his ex-captains Kim Hughes.

No matter the occasion or match – club, state or Test – Thommo would waltz in and with that almighty javelin-style wind-up of his he’d let ’em rip, frightening the daylights out of anyone standing twenty-two metres away.

Queensland had batted first on the lightning-fast WACA, its final wickets tumbling quickly in the final session, leaving Western Australia with an awkward half an hour to bat before stumps.

‘You could see our openers getting edgier and edgier as the last wickets fell,’ said Hughes. ‘It’s always a thankless task having to go out and open when you’ve got just seven or so overs to face that night.

‘We took the last pole, came in and wished the openers good luck. When you bat at four or five you’re happy. You can wait for the next day. It’ll be nice and sunny. The sting is out of the ball and you can make hay.

‘From Thommo’s second ball, Wally Edwards fended it off his nose and it went for 6 over second slip. I thought, “Gees, that looked a bit slippery.”

‘Immediately our three pacemen, Dennis [Lillee], “Clemmy” [Terry Alderman] and Mick Malone began to debate who was going to be asked to be the nightie [nightwatchman]. Fast bowlers are always expendable. And there was no fast bowlers’ truce in those days. Thommo really wanted to let you know that he was on the park. He wanted to bowl quicker than Dennis. He didn’t care who he knocked over.

‘Our twelfth man was busy stacking the full-strength beers into the bathtub, making sure they were icy cold. That was an absolute non-negotiable when Rod Marsh was captain.

‘The quicks saw how fast Thommo was bowling and retreated. One hopped into the showers and the others snuck an early beer. Fortified by several in a hurry, they put their heads around the corner – making sure Marshy had seen the cans – and yelled, “Where do yer want us to bat today? We’ll kill ’em.”

‘We obviously couldn’t send them out,’ said Hughes. ‘We lost a second wicket. Suddenly I was in.

‘I walked out, collar turned up, buttons undone, swinging the bat like Ian Chappell. I’d seen him do it a dozen times on the telly. If Ian Chappell could do it and he was an Australian cricketer, then I could do it too.

‘Bruce Laird was still in and as I passed, offered a “good luck”.

‘ “Oh, I’m all right,” I said. “I don’t need it … I’m ready to rock ’n’ roll.”

‘ “Oi,” he said. “Some bastard is going to get killed here today.”

‘I stopped and I thought a little. Well, it’s not going to be Thommo. He’s looking pretty good. Who is it? Lairdy’s warning just straight went over my head. I’m twenty-one going on fifteen.

‘I took guard. Leg stump as always. Then I scratched my box about twenty times. Again a Chappelli thing. Watch it. Hit it. Get out of the way. A quick look around the field. Gees, there’s no-one in front of the wicket. Not one. You bloody beauty. Eight balls, bat on ball, eight 2s are 16. I’m on my way to another hundred here. How good’s this game!

‘A quick walk down the wicket, patting down the divots. You know the crowd is looking at you. I’ve seen blokes do it on concrete. You think, “Mate, that’s crap. Get back to your crease. Get on with it.” But that’s what the good players do.

‘When someone like Thommo is bowling, you’ve got 0.4 of a second to react. So if I said, “One thousand,” you’ve got less than half that time. Get on the back foot. Don’t get on the front foot – otherwise you’re going to get killed. Watch it. Hit it. Get out of the way.

‘The Wacker was very, very quick back then. I was about to settle over my bat, before realising just how far back from the wicket Queensland’s wicketkeeper John Maclean was. I didn’t think he was ready – he was back by the sightscreen. I’d never seen anybody back that far. I thought, it’s not going to carry, you’d better come up a little bit. We were 2-10 and then he said something really ordinary about my mother. I thought, bugger it, why does Mum always cop it? She’s nice.

‘I pushed at the first four … all blurs. I didn’t see any of them. “Come on, son,” I said to myself. “You’re on zero. The night before, you were going to get a hundred. C’mon.”

‘From the other end, operating into a strong sea breeze was Geoff Dymock. Left arm, good bowler, friendly. Well, friendlier than Thommo anyway. Boy was I keen to get up his end! Eight balls, eight 4s are 32. Lairdy was on the front foot and looked a million bucks. He eased one into the covers. An easy one. I got halfway down only to be sent back. He squeezed the next through the gap. An easy single. “Come 2!” he said, scuttling up to my end and back again like it was Easter and he was in the Stawell Gift.

‘When we got together at the end of the over, he told me matter-of-factly that he had his end covered. Fair enough. He was the senior player …

‘Somehow I got through, but boy was Thommo rapid. He knew he had only four or so overs to bowl that night and he let every one of ’em rip … ‘Fast? Yep. Furious? Yep. Frightening? Double yep.’

***

Cowboy Colin

So rotund was the recalled Colin Cowdrey during the 1974–75 summer of speed that he was dubbed ‘the Pear’. But under his cricket gear he’d wrapped himself in foam rubber like the Michelin Man. He knew the challenges and dangers the batsmen faced playing dodge-ball against Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson.

On his Test recall in Perth, he batted two hours in the first innings and almost two and a half in the second, having been plucked from in front of his cosy south-of-London fire and favourite easy chair into the smouldering cauldron of Test cricket 13 000 miles away. One old fan remained unimpressed and kept yelling, ‘Cowboy … get on with it!’

Once Cowdrey bowed to him and the man erupted, ‘Cowboy, I used to come and watch your father play and he wasn’t any good either!’

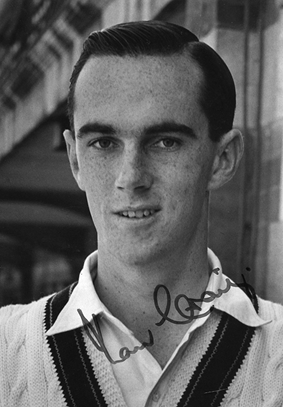

SIX TOURS DOWN UNDER: Much-travelled Colin Cowdrey in the early ’50s

***

Few tucked into their food as eagerly or as often as the majestic Pakistani strokemaker Majid Jahangir Khan, who bought an electrifying star quality to English county and University cricket in England in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

During a club cricket tour in the English midlands, his team had arrived in town too late to eat at a restaurant, so ordered what they thought was thirty-six rounds of club sandwiches off the hotel menu.

An hour and a half later a waiter appeared staggering under the load of 72 sandwiches stacked onto two trays. While there were six or seven of them, the second tray was untouched so Majid was called for from his upstairs room and he proceeded to happily polish off the lot.

So fond was Majid of ice-cream that Glamorgan’s captain Tony Lewis would offer him a cornet for every 10 runs he made over 50. His favourites were doubles. Once when dining with some fellow undergraduates in London, Majid said he was so hungry this particular night that he would eat the whole meal again, including steak, peas and chips followed by ice-cream with chocolate sauce.

The restaurant owner said if he could do that he’d give him a free meal next time he came into the restaurant. Majid ate the second meal and said he could have come back for thirds but had to be up early the following morning. He won his freebee.

***

The other side of Wally Grout

Dare throw a ball wide or short to Wally Grout and he’d give you the full stare treatment as if to say: ‘These hands are my life. Protect them.’

Grout was thirty before he was selected by Australia and he played on until thirty-seven despite a heart problem which eventually saw him die young, at forty-one.

A wonderful cricketer and a larger-than-life character, he smoked two packets of cigarettes a day and had a gambling addiction that saw him return from trips to England with only the clothes he had on his own back. All his gear had been sold, or left behind, to help pay for his losing bets and follies.

In 1961, his wife Joyce bailed him out. He’d returned with a brace of debts banks in Australia didn’t want to know about. He promised faithfully that he would stop, but he couldn’t.

Joyce Grout knew how significant his debts were in ’61, but they were nothing compared with those he amassed in 1964. The team traditionally played a match in Hobart before the ship journey to the UK and Grout invested much of his 1000-pound tour fee with bookmaker Ted Pickett at Elwick and lost badly.

Within weeks he was in the red with English bookie Sid Gordon, his entire tour fee now spent. Grout asked his wife to assist him again but she refused.

Australian jockey Billy Pyers gave Grout the tip to back his horse Baldric II in the Epsom and it stormed home at 20/1. But it was one of the rare wins and by the tour end, he was flat broke and pawning his equipment.

On Grout’s return home, Joyce was amazed how little actual cricket gear he had left. She knew he had been gambling again, but had to sit down when he told her how much money he owed.

As grandson Wally Wright said in a biography of Grout, published forty years after his grandfather’s death, divorce was frowned upon in those days. ‘Few people, however, would have blamed Joyce if she had taken her two young children and walked out on her husband. But Wally was the love of her life. Joyce went to her bank manager for a loan … and month after month following that tour, Wally would send post-dated cheques to various bookies in Australia and England to lessen the thousands of dollars he owed.’

See also: Two hits for his hundred

***

Seeing ’em like a football

Just retired from Test cricket, the legendary Alan Davidson couldn’t understand how even the Western Suburbs fourth-graders were regularly bowling him out during the 1963–64 pre-season. ‘I thought something must be wrong so I went to have my eyes checked and started batting in glasses,’ he said. ‘All of a sudden I could see the ball more clearly than ever. It was like a football!’

‘Davo’ made 542 runs and took thirty-eight wickets that season and followed with another 683 in 1964–65. In an exhilarating hour against Bankstown in the New Year of 1964, he hammered nine 6s and seven 4s in his 116, made another ton in the semifinal before taking ‘eight-for’ in the final. He was a seriously fine player, and Wests played off for the title six years out of nine during Davidson’s unforgettable reign.

***

One for the grandchildren

After a lifetime of going in at the head of the order, sub-district legend John Birch was virtually unflappable … but not this day.

As he took strike at his favourite Camberwell ground, the balding bloke at the other end pacing out his run-up somehow seemed familiar …

Could it be? Yes, it was …

The Australian Cricket Society had recruited famed expressman Frank ‘Typhoon’ Tyson, who was living and working in Melbourne, to take the new cherry for its inaugural playing season. In came Frank, still with plenty of vim and purpose in his run-up and delivered his first over at a comfortable fast-medium as befitting one on the verge of his fortieth year.

His new ball partner Mike Delves was similarly military and another over passed without dramatics.

At the start of the Typhoon’s second over, the Test legend overpitched on Birch’s leg stump and the veteran calmly stepped inside it and lifted it high over the square-leg fence for a maximum!

As the ball was being retrieved and Tyson was still eyeballing the batsman, wicketkeeper Ken Woolfe suggested to first slipper Delves that ‘Frank may not have liked that much. Let’s go back a pace or two … maybe even three!’

Marching back past his marker, Tyson fairly thundered in and delivered at a much, much faster pace. It was short and rearing, just on the line of the off stump.

Birch attempted to half evade and half play it and it just flicked a glove before cannoning into Woolfe’s gloves.

There was something of an appeal – more a polite enquiry than a full-throated ‘Howzaatt’ – and on hearing the appeal and without even looking at the umpire, Birch tucked his bat under his arm and headed off to the pavilion, saying, ‘That’s close enough for me!’

It may have only been an over and a half but he’d faced the Typhoon – and lived!

STILL FAST: Even into his late thirties, Frank Tyson could still generate genuine pace

magazine

***

Scary times

It wasn’t the first time the Typhoon had scared the living suitcase out of an opposing batsman. Gloucestershire’s George Lambert was sent in as a night watchman late one afternoon in 1954 against a Northants XI, which included F H Tyson, then at his most hostile.

Normally George batted at seven or eight when the ball was older, softer and less shiny. This day Tyson and his pace partner R W ‘Nobby’ Clark were bowling a brand new ball at discomforting speed and to Tyson’s first, Lambert only just decided to let it go when it was in the gloves of the keeper Keith Andrew.

As Tyson was launching himself for his second delivery, Lambert was gripping the bat tightly, talking to himself, ‘This bloke ees quick. Be ready. Move your bat. Move your baatttt.’

By the time he’d finished talking to himself, the ball was again in Andrew’s gloves. He again hadn’t lifted his bat.

‘By Christ,’ said Lambert. ‘I don’t think I saw that.’

The third speared in, again at supersonic speed, closer to Lambert’s off stump and this time he touched it behind. There was a stifled appeal and without looking back, he turned for the pavilion.

‘Where are you going, George?’ asked Andrew, the keeper. ‘Come back!’

‘What for?’

‘It’s a 4.’

Lambert’s edge had smashed straight through the hands of Fred Jakeman at first slip – standing about thirty metres back – and sped straight to the ropes, hit a boundary post and rebounded almost all the way back to the slips.

Somehow a chastened Lambert survived the rest of the over and walked off mightily relived to be presented with a double scotch as he came in.

‘Get this down yer, mate,’ said teammate Sam Cook. ‘Looks like you need it. Frank will be quicker in the morning!’

***

The Breeze

Typhoon Tyson’s son, Philip, was schooled in Melbourne at Carey Baptist Grammar. He liked to take the new cherry but never ever bowled at anywhere near the rattling pace of his famous Dad. His schoolmates called him ‘the Breeze’.

***

The Frog

Alan ‘Froggie’ Thomson was just fourteen when it was suggested his chest-on, wrong-foot, windmill bowling action needed serious modification.

‘We were at the schoolboy championships at Melbourne Grammar and [coaches] John Miles and Frank Tyson tried to change me,’ the Frog said. ‘They were all very well-meaning, but they had me in tears. Back home I was told to bowl the way I liked, so I did. I never worried about it [changing] again. I just bowled the same way. Being chest-on, I was probably ahead of my time.’

Asked how he had developed his unique action, which was to terrorise club, state and one or two international batsmen in the mid to late ’60s, Thomson said he was no gymnast and was always scared of falling over as he approached. So he developed his high-kneed run-in and it just felt natural letting the ball go off the back foot.

‘I first bowled like that with the Presbyterians in 1955–56. They didn’t give me another bowl for another two years. But I was the only one from that team to play Test cricket!’ he said.

The fastest to 100 wickets for Victoria in a record-equalling nineteen games, the Frog was chosen for four Ashes Tests in 1970–71, taking twelve wickets. In his last Test, in Adelaide, he opened the bowling ahead of a young fellow from the west by the name of Lillee.

A week earlier, on the third morning of the rescheduled Melbourne Test – in front of a crowd of more than 65 000 – Thomson dismissed Ashes icons Geoff Boycott and John Edrich in what he regards as the highlight spell of his career.

‘They clapped me off at lunch,’ he said. ‘I had something like two for 20 at that stage. Unfortunately, it was downhill after that. I never did get that high again.’

Thomson’s shock value in releasing the ball earlier, off the back foot, often caught opposing batsmen unaware. In the first ball of the Ashes series at the Gabba, Boycott hadn’t even picked up his bat before Thomson’s release. Luckily for Boycott it was (wrongly) called a no-ball.

Thomson bowled at a rapid rate, without being express, his off-cutter a major weapon. A straighter one, a semi-leg cutter added to his variety.

Another of his proudest moments at national level came when he shared the new ball with Graham McKenzie in the opening Test of 1970–71. He took a Warne-like one for 156 on debut but he reckoned hundreds of others would have loved to have been in his shoes.

International cricket was a tough forum. Opposing players of the quality of England’s Brian Luckhurst and New Zealand’s Bevan Congdon was like bowling against a barn door.

‘Luckhurst was a terrific player,’ Thomson said. ‘I might have got him once, but that was it.’

Thomson was no fast-tracked wonder boy. He arrived at Brunswick Street, Fitzroy’s original home, in 1961 and played in the fourths and the fifths. The following year he was given a seconds game, but it wasn’t until he turned nineteen, late in the 1965–66 summer that he was tried at senior level and took his first ‘five-for’, on debut against Richmond.

‘I became a permanent in 1966–67, the year we won the flag against Essendon.’

Thomson and Eddie Illingworth took almost ninety wickets for the season, Thomson loving the extra bounce of his home ground wicket which saw even the spinners occasionally bounce the ball over the keeper’s head.

In a pace-rich era, the Illingworth–Thomson combination was as menacing as any in Melbourne club ranks including John Grant and Ken Adams (Essendon), Ron Gaunt, Arthur Day and Tony Leigh (Footscray) and Nigel Murch and John Ward (St Kilda).

Come the much-anticipated final that 1966–67 summer – it was the year after Bill Lawry’s epic 283 in the final against Essendon – Thomson recovered from an erratic start to take six for 72 as the Bombers collapsed for just 161, Fitzroy winning the pennant after replying with 348 including a century to captain Jack Potter and 99 to opener Ron Furlong.

‘Once Froggie got the ball to bowl it was hard to get it back from him,’ said Potter. ‘In that final against Essendon he bowled poorly at the start of his spell, but with a bit of encouragement and kidding came good. I told him that he was our best bowler and we needed him to fire. “Show ’em how good you are, Frog,” I said, “otherwise we may be in trouble.”

‘He bowled twenty-five eight-ball overs straight and took six of the best. At times he was almost running back to bowl as quickly as he was running in. Today they would have rested him after about six overs, but not the Frog. He was a footy umpire and was super fit. Once he got it right he was difficult to play and that day was his day.’

WRONG-FOOT WINDMILLER: Alan Thomson delivers the first ball of the 1970–71 Ashes series in Brisbane. Geoff Boycott hasn’t even lifted his bat!

Bruce Postle

***

Strike me pink!

KG ‘Ken’ Cunningham, the long-time voice of South Australian sport, had just been offered the South Australian cricket captaincy, one of the great jobs previously held by some of his heroes including Sir Donald Bradman, Ian Chappell and Les Favell.

The same week, 5DN radio’s station manager Paul Linkson invited him to host a sporting talkback radio show. He made it clear that he couldn’t do both jobs: cricket and media.

Cunningham discussed the pros and cons with his wife Sandra, who encouraged him to look at the bigger picture. ‘But I stutter and talk too fast … I’ll probably last only one survey,’ said Cunningham.

The following morning on the way to his fulltime work at the Newmarket hotel, he thought long and hard and said, ‘Nah, I’ll stay working here and keep playing cricket.’

When he pulled up, he said, ‘Nah, bugger it, I’ll give 5DN a go’ … beginning a near forty-year association pioneering Adelaide talkback radio.

His most famous line? ‘Strike me pink!’

CHANGED HIS MIND: Ken Cunningham

***

Thanks but no thanks

Given his first cricket bat at four and taken to Bramall Lane for the first time at five, Michael Parkinson had aspirations to skip straight from Barnsley Grammar into Yorkshire CC’s first XI and onto the English XI. He simply loved cricket. Trouble was his skill didn’t quite match his ambition.

In his late teens he accompanied his mate Dickie Bird to the Yorkshire nets where the coach and long-time Yorkshire pro Arthur ‘Ticker’ Mitchell was keeping a close watch on the newcomers.

Bird was standing near Mitchell as Parkinson trialled.

‘Is he a mate of yours?’ asked Mitchell.

‘Yaasss.’

‘Has he got a job [outside cricket]?’

‘Yaass, he’s a reporter.’

‘Taall ’im to keep on reportin’!’

And that was master interviewer Michael Parkinson’s last serious tilt at cricket.

***

‘If you ever do that again, I’ll kill you’

Before the days of safety issues and perimeter ropes, boundaries were truly earned and all-run 5s occasionally scored, especially at the bigger grounds like Adelaide straight and Melbourne square.

Western Australia was playing the Vics in Melbourne. Veteran captain Tony ‘Bo’ Lock was in with the younger and far sprightlier Ian Brayshaw.

Other than a short leg and a straightish fine leg, the onside was completely vacant and Brayshaw sweetly timed a shot off his toes and he and Lock motored up and down the wickets, taking 5 as the ball rolled almost ninety metres away and finished just short of the gutter at forward square.

At the end of the over, a very red-faced Lock called his partner into the centre of the wicket. ‘Brayshaw,’ he said. ‘If you ever do that again, I’ll kill you.’

Had he been running with a younger teammate like Ross Edwards, Brayshaw said they would have easily run 6, if not 7.

It was also in Melbourne where Lockie once burnt a brand new bat after he’d made a pair. Teammates were hiding in the toilets trying to conceal their laughter as Lock walked back in high dudgeon. Instead of flinging the bat from one side of the room to the other, he sat down calmly, reached for his cigarette lighter, turned it up to full blaze and calmly set fire to the willow.

***

Heavyweight opener Colin ‘Ollie’ Milburn had an aversion to running, except between the wickets. At pre-season training at Northants one afternoon, stand-in coach Dennis Brookes called for a cross-country run – ‘and at good pace please lads’.

Eighteen-stone (114-kilogram) Milburn was soon back at the rear of the field, his only company a groundstaff rookie who’d taken pity on him. Slower and slower big Ollie trudged before coming to a complete standstill. Hands on his hips, he was about to sink to his haunches when around the corner came a milk-float …

Thinking on his feet, Milburn stuck out a thumb, and got the milko to stop and drive them past the pack and all the way to within 100 metres of the finish line, where they got out. The triumphant pair completed the race a minute or two ahead of their astonished teammates.

‘What kept you boys?’ asked Ollie with his trademark melon grin.

***

He said it

‘There’s no such thing as a really bad Australian team.’ – cricket journalist Ron Roberts

***

The Little Fave

Johnnie Martin, the big-hitting wrist spinner from Burrell Creek, near Taree, once hit a ball on top of the old Hill Stand at the Sydney Cricket Ground. It was one of the biggest of more than three hundred 6s he struck during his breezy eight-Test career.

Martin was also a canny wrist-spin bowler who on his memorable international debut against the West Indians in Melbourne once took three wickets in four balls: Rohan Kanhai, Garry Sobers and Frank Worrell!

Whenever Martin hit the batsman on the pad, his standard practice was to appeal quietly. Invariably the umpire would say ‘not out’. But as soon as Johnnie felt it was a close decision, he’d give a big, vocal, highly convincing ‘Howzzaaattt!’

It often worked too. Few could work the umpires like ‘the Little Fave’.

See also: Knockout punches

A FAVOURITE: Johnnie Martin

***

Can you sign please, Wes?

Max Walker was just a kid in short pants when he became truly ‘hooked’ on cricket.

A Tasmanian Combined Xl was playing the West Indies at the TCA Ground in Hobart and young Max was determined to secure the autograph of the famed express bowler Wes Hall.

Seeing the front door of the dressing-room manned, he opted to go around the back and shimmied in through a small, louvered toilet window.

‘My mate bunked me up and I pulled out all the louvered blades from the window. Up I went and I was in. The dressing-room was old and antiquated with hardly any light. All I could see were the whites of their eyes and their teeth. One said, “Hey man, what are yer doin’ in here?”

‘I mumbled something about wanting to meet Wes Hall and thrust out my autograph book. The great man himself signed it and I got nine or ten others of the magnificent 1960–61 team as well … as a very impressionable young kid, I was in heaven.’

***

Fred and Ginger

As a Test selector, Len Hutton was one helluva opening batsman. He didn’t enjoy having to make decisions which affected careers. There was an earnest debate one afternoon about the qualities of two or three emerging young ones. Len remained silent throughout until chairman Alec Bedser asked for his opinion.

‘Did you ever see Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance?’ asked Len, his mind far away.

***

Like father …

Wagon wheels of any of Brian Booth’s finest innings always were off-side dominant.

‘Our house [in Perthville], a fibro, was on the on-side of the wicket and Mum didn’t like us hitting the side wall of the house in case it damaged it, so I became far more proficient on the off-side than the on,’ he said.

‘We had our own gravel granite pitch in the backyard and we’d play either there or outside on the street until it was too dark to see the ball any more. Dad would have put in a big day at the market garden but he’d bowl to us all for hours on end. He loved it and as a result, so did I.’

***

Magic substance

So dominant was Richie Benaud from the opening match in South Africa at Kitwe (1957–58) where he took a career-best ‘nine-for’ that locals dubbed him ‘Bwana’ (Master). Five of the nine came from lbws from back-spinners and his newly perfected flipper.

For the first time in years he’d been playing pain-free, thanks to a chance meeting with a New Zealand chemist in seaside Timaru six months earlier.

Touring with an Australian ‘B’ team, Benaud was having a prescription filled when the chemist noticed his red, raw spinning finger. ‘How long has it been like that?’ he asked.

‘A long time.’

‘Might have something here which helps.’

The chemist, a Mr James, foraged below the counter and emerged with a tiny bottle of calamine lotion and some boracic powder. He prescribed it regularly, mainly to returned servicemen looking to heal leg ulcers.

Benaud had once been told by Bradman Invincible Colin McCool that he should never give up his hunt to find a remedy for his often bloodied spinning finger.

From being initially sceptical at its likely benefits, Benaud was soon delighted at the results. He filled the wound with the waxy substance and covered it with sticking plaster. Within days his spinning finger began to heal and toughen like it was the off-season and soon Benaud was able to bowl without any inconvenience, triggering a career-best two or three years in which he inherited the Australian captaincy and was clearly the most formidable slow bowler in the world.

***

‘It’s out of the question, you’re playing’

Australia’s queue-jumping captain, 22-year-old Ian Craig declared his form ‘questionable’ and said that he could no longer command a batting place. He intended to step down. With scores of just 14, 17, 0, 52 and 0 in the opening three Tests, he felt he was a liability and said so.

It was late in the 1957–58 tour of South Africa. Australia remained unbeaten. Fellow touring selectors Neil Harvey and young Peter Burge, a first-timer, were stunned.

Harvey, as vice-captain, would have been the new leader, so had plenty to gain. But within seconds he reassured Craig that he was wanted and that no Australian touring captain had ever been dropped before. ‘I wasn’t going to be a part of it,’ he said. ‘I told him, “It’s out of the question, you’re playing.” ’

Craig was outvoted 2–1 and played the final Tests in Johannesburg and Port Elizabeth, scoring 3 and 17.

With an average of less than 15 over the five Tests, he had underachieved massively. But captaining a team which went undefeated and won the Tests 3–0 on its way to becoming world champions twelve months later remains the highlight of his career.

‘It was a rewarding and happy tour and led to a great time in Australian cricket,’ Craig said. ‘Everyone had a fabulous time and enjoyed everyone else’s company. There was never any animosity or friction between players. I’d been on tours when there was but there was nothing like this this time.’

Craig said the previous tour to England in 1956 had been a losing, unhappy affair. The personality differences within some in the touring squad, especially captain Ian Johnson and vice-captain Keith Miller had tarnished what normally should have been a career highpoint.

‘Defeat does tend to generate negative attitudes. It was sad for those players who had reached the end of their careers. To some extent that was why I got the captaincy [ahead of more experienced players],’ he said. ‘There was a report from team management [after the tour]. Ron Archer and myself apparently rated as future captaincy material. Ron was injured on the way home and unfortunately hardly played again [even for Queensland], leaving me …’

New captain Craig scored centuries in the opening two major games of the South African tour, but rarely got going again and averaged just 36 in all first-class games, the tour being dominated by emerging all-rounders Richie Benaud and Alan Davidson.

‘We were optimistic we’d do well,’ Craig said. ‘We’d struggled in England on the previous tour in conditions which favoured spin bowling. The conditions in South Africa were closer to ours. We were expecting to do better than the press gave us credit for.

‘The South Africans had a very good side and were expected to win but didn’t know how to. The confidence and enthusiasm we developed from winning was enormous and made all the difference. We won our first seven or eight games. We were playing good opposition and beating them comfortably with everyone performing well. It gave us the opportunity to kick on into the Tests. Richie and “Davo” were both major forces. So dominant were they with bat and ball that we felt we had thirteen players playing eleven.’

Asked about being appointed Australia’s youngest-ever captain, Craig said simply, ‘I didn’t expect to get the captaincy in my time. It was premature in many respects but when you are offered the captaincy of Australia you don’t decline it. I didn’t think I had a choice.’

Leading into the South African tour, Craig had a trial period as captain on an autumn-time tour to New Zealand where the Australian ‘B’ team, including Harvey and Richie Benaud, won seven of its ten matches. During the first unofficial test at Lancaster Park, manager Jack Norton decreed a mid-match curfew – everyone had to be back in the hotel by 10 p.m. Craig challenged him immediately. ‘I’m sorry Jack,’ he said, ‘But I have arranged to go out to dinner tonight and so have Neil [Harvey] and Peter [Burge] and we’re going.’

In South Africa he implemented an ‘amenities’ committee which levied fun fines for so-called ‘misdemeanours’. Fines for walking away from earbashers at official functions to repeating the same story bolstered the slush fund and guaranteed an end-of-trip party to remember.

See also: Pace like fire

HE ASKED TO BE DROPPED: Ian Craig

***

A hero for thousands

Australia’s first post-war captain Bill Brown was a hero for thousands, especially for young Queenslanders like Test-opener-in-the-making Ken Archer.

‘I was a little boy when Bill moved up from NSW and became a Queenslander,’ said Archer. ‘I’d go with my schoolmates to watch him play. It wasn’t long before he was one of us. We Queenslanders are pretty parochial!

‘Bill was a lovely, graceful player and quite talented too without quite stepping up to the status of the real greats.

‘When I did join him in the [Sheffield Shield] team, he’d regale me with stories about the ’34 and ’38 [Ashes] tours and making that double hundred not out at Lord’s. Later on he’d tell the younger ones the same stories again and turn to me and say, “You remember that Kenny don’t you!”

‘ “Not quite Bill,” I’d say, “I was only six at the time.” ’

TOO YOUNG TO REMEMBER: Ken Archer

***

The man was a genius

As captain, Keith Miller was always different. Arriving late to one Shield game in Sydney after the birth of his fourth son and still smelling of the celebratory rum he’d been downing, Miller walked out with his normal white dress shirt still on and shoelaces undone. There’d been a short rain delay and he’d made it by just minutes. ‘Right,’ he said. ‘Who bowls in this team?’

Looking around he sighted Pat Crawford, a decidedly slippery right-armer. ‘Oh you bowl a bit Pat … you start …’

Crawford duly bowled the first over from the Randwick end. It was a steamy Sydney morning, lots of humidity and with a south-easter right across his arm.

With the over completed, Miller again looked around. ‘Who else bowls? Oh “Davo”, you bowl a bit. Have a go …’

Just as Alan Davidson was pacing out his run-up, Miller stopped him and said, ‘Hang on a minute, Davo, I’ll bowl,’ and walking back ten or so yards – he didn’t bother to measure it – Miller sauntered in and with his second delivery jagged an off cutter from wide outside the off stump to only just miss middle.

Everyone stopped and stared, especially the batsman, South Australia’s Les Favell.

Seven overs and one ball later, Miller had seven for 12 and South Australia was all out for 27 – a record low.

The man was a genius.

INSPIRED: Keith Miller

***

‘And where were we, Dud?’

Alan Walker was charging in at Sid Carroll in a Sydney grade club match at Chatswood. Few left-armers had ever been as slippery as young Al, and his club captain Keith Miller had a field to suit: three slips, a gully and a short leg.

Carroll was not going to die wondering, and anything short of a length and angled across him he was looking to lift high, wide and handsome, over slips or gully to the unguarded third-man fence.

Newbie Peter Philpott was in the gully expecting a slash at any moment. The slips, however, seemed less focused, Miller as always talking about the races with keeper Dudley Fraser and first slipper Eddie Robinson.

Finally Carroll got some bat to one and the nick went at rapid pace wide of Miller. He nonchalantly plucked the ball with his left hand, flicked it to Fraser and carried on talking about the races.

***

The Fitzroy urchin

Champion-to-be Neil ‘Ninna’ Harvey had only just turned thirteen when he scored a century in each innings for Fitzroy thirds at Old Scotch in the Metropolitan Cricket League’s grand final on the last two Saturdays of March in 1941–42. He’d borrowed his brother’s bike and ridden the two miles from the family’s rented house at 198 Argyle Street, Fitzroy past the MCG and onto Swan Street.

Harvey was thrilled to be even playing. He’d made 77 in the final home-and-away game but felt older, more experienced players would be included for the final.

A schoolmaster at Falconer Street Central allowed him to borrow one of the school’s Harrow-sized bats, complete with Edgar Mayne’s signature high-up on the face.

With his bat and gear all in a Gladstone bag perched on the handlebars, it was a wobbly ride there but a triumphant one back as he’d made 101. By stumps Fitzroy already had a first innings lead.

‘No-one was more surprised than me,’ Harvey was to say of his achievement. His father, a caretaker at the local Lifesavers factory, had promised his boys ten shillings if they ever made a century and Neil was to double it up the following weekend. When the game was called off early, he was 141 not out, batting a second time.

Following the game, Fitzroy’s captain Bill Vautin asked Melbourne’s captain Arthur Dickens if he’d like to meet young Harvey … ‘I think he’s going places Artie.’

‘Meet him?’ said Dickens. ‘Don’t you think I’ve seen enough of that little so-and-so out there [in the middle]?’

By fifteen, Harvey was a regular in Fitzroy’s first XI and in time all six Harvey boys – Merv, Mick, Harold, Ray, Neil and Brian – were to play first XI, Merv also representing Australia and Mick and Ray playing Sheffield Shield.

As kids, the boys shared the same bedroom and each weekend would play their backyard tests in a narrow cobblestone laneway, using an old kerosene tin as a wicket. A tennis ball dipped in water tended to skid off the cobbles and batsmen had to be both precise with their feet and brave, as the ball would often rear at all sorts of odd angles. Straight drives were the favoured scoring shot, but also the most dangerous as any which happened to be lifted would endanger a neighbour’s window directly behind the bowler’s arm. ‘More than once games had to be called off early – Dad had to foot the bill for the broken windows,’ Harvey said.

A teenage Harvey’s cricket education was honed here and at nearby Brunswick Street, home of Fitzroy, producer of four Test cricketers and thanks to the Harveys, soon to have six.

Fitzroy’s coaches were Joe Plant and Arthur Liddicut who would bowl at Harvey for hours, all the time emphasising the need to be balanced and fast on his feet. Plant would place some coins at various lengths and encourage Harvey to dance to the spot, without a ball. With his head perfectly still, he’d glide to the designated spot and quickly became adept at reaching the ball on the full before it had a chance to spin.

‘He was lightning fast on his feet,’ said one of his most noted opponents, expressman Frank Tyson. ‘He was masterly against spinners but he was also an extremely fine player of pace. You knew you had to get him out early, as once set he’d always threaten to make a big score.’

Soon, with the retirement of Don Bradman and Lindsay Hassett, Harvey was Australia’s stellar batsman, despite wonky eyesight which never allowed him to read a scoreboard. Once an optometrist in Johannesburg even asked him, ‘Who leads you out to bat, son?’ He recommended he wear glasses immediately, but Harvey was too embarrassed, even though when he first put on the glasses, ‘it was a brand new world’.

‘It wasn’t the done thing in those days,’ he said. ‘I know now I was a bloody fool. I batted the last five years of my Test career with poor eyesight and my form fell away.’

From the time he advanced grades at Brunswick Street, he seemed destined to represent his country. A ton in his second Test at the MCG and another on his memorable Ashes debut at Headingley were unforgettable 1948 milestones.

Never stumped in his entire Test career of 137 innings, he was only twice struck above the waistline in his entire representative career: by Wes Hall in the ribs in Sydney and Ray Lindwall on the point of the shoulder at the Junction Oval.

The highest of his twenty-one Test centuries was 205. Perhaps his greatest knock was 151 not out on a worn, pockmarked pitch turning sideways at Durban in 1949–50. He also made a fluent 96 on a matting wicket at Dacca (now Dhaka) against the medium-paced Pakistani master Fazal Mahmood in 1959–60 – an innings Richie Benaud described as the greatest Harvey played in his time.

Ninna’s outstanding batting record was complemented by his fielding prowess in the covers and in close, Benaud saying Harvey’s balance and brilliance in the field was simply unsurpassed. Don Bradman said the power of Harvey’s throwing arm made him a dangerous fieldsman from even the furthest point on a ground. In his last Test, aged thirty-three, he took six catches, from the slips to the outfield.

At Lord’s in 1961 he captained Australia when Benaud was injured. Awarded an MBE in 1963, the year of his retirement, he was a national selector for twelve years and in 2014 had a bronze statue unveiled in his honour at the MCG, joining a pantheon of greats to be similarly honoured including Don Bradman, Bill Ponsford, Keith Miller, Dennis Lillee and Shane Warne.

BRONZED: The Neil Harvey statue unveiled at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in 2014

SDP Media/MCC

***

South Africa’s Neil Harvey

The only fieldsman in the world who was to consistently rate with Neil Harvey was South African Colin Bland who was worth a place in just about any Test team on his fielding and throwing abilities alone. During England’s 1964–65 tour, some of the MCC batsmen when running between wickets would call, ‘No! Yes! Come just 1 … [it’s] Colin!’

***

Bragging rights

Two pubs in an English village were preparing for their annual Sunday grudge match and the all-important bragging rights.

As the hour of the game approached, one of the captains was in the cricket ground car park impatiently waiting for the star ‘ring-in’ he was counting on to help reverse a run of recent losses.

The captain was becoming quite agitated when a horse that was leaning over the fence asked him, what was the problem?

The captain had never known a horse to talk before, but told him anyway … ‘My star player hasn’t turned up … it looks like we’ll have to field one short.’

‘That’s all right,’ said the horse. ‘I’ve played a bit. I’m happy to help out.’

A quick check of the rules found nothing to preclude the horses’ participation. What the hell, thought the captain. A talking horse will get a few laughs. We always get a hiding from the other mob, so why not?

Having lost the toss, he walked out beside the horse, preparing to take the first over himself. He had no idea who would bowl from the other end. ‘Let me open up,’ said the horse. ‘I’ve bowled a bit.’

‘Why not?’ thought the captain.

Not bothering about a run-up, the horse rose on his hind legs at the popping crease and delivered the first ball, full and straight. So shocked was the opposing batsmen at the horse’s nice rhythmic action that he watched the horse rather than the ball and was clean bowled.

Everyone had a great laugh before the horse proceeded to bowl five more of them with high-speed in-swingers à la Dale Steyn or Darren Gough in their pomp. He had six for 0 and all the guns from the opposing Pub XI were out.

The captain was ecstatic. He was already rehearsing his victory speech. As he marked out his run-up to bowl into the breeze from the other end, the horse quietly settled into a place at slip.

‘Just come in a little bit,’ called the captain.

‘Sure,’ said the horse.

To the very first ball, a little swinger, the batsmen snicked a ball fine and the horse dived brilliantly to the left to take an excellent catch in his outstretched hoof. It was 7-0.

And it happened three more times, the captain having four for 0, the opposition all out without scoring even a single!

The captain was over the moon and asked the horse where he batted. Needless to say he’d ‘opened a bit’.

‘Come out with me then,’ the captain said.

The captain wanted to hit the winning runs so he took strike. Forcing the first ball through the covers, he called and took off. It was an easy one, probably 2 and it was game over. But as he got to the other end, he noticed the horse was still there, leaning on his bat. Distracted, the captain stopped before sprinting for the other end and diving headlong for the crease only to be run out … just.

‘What the hell is going on?’ called the disgruntled captain over his shoulder as he was dusting himself off. ‘A bloody talking horse who plays cricket. You clean bowl six guys and catch the other four. But when you’re called for a simple run, you can’t manage it. What’s the matter – can’t you run?’

‘Of course I can’t run,’ said the horse. ‘If I could run I’d be at Ascot, not stuffing around here playing cricket!’

***

King of the MCG

Local hero Keith Miller was in the middle of his epic pre-lunch spell in Melbourne when he claimed three key wickets for next to nothing. In at No. 5, Denis Compton was all at sea against one which seamed and lifted like a high-speed leg-cutting bouncer. It was truly unplayable. The crowd of more than 60 000 were roaring their appreciation and willing Miller to bowl even faster.

Stopping in mid-pitch at the end of his follow-through, Miller eyed his close mate and said, ‘Compo, you never seem to get any better? Don’t you ever practise?’

He walked back to his mark past the non-striker Colin Cowdrey and said, ‘It’s amazing young Colin. They keep on picking this joker, Compton – I suppose for his looks – but I have been bowling him that same ball since 1946 and he still doesn’t wake up to it.’

At the top of his mark he again called down the wicket to Compton. ‘Are you awake now, Denis?’

The next one was right on middle stump and Compton defended it capably. ‘Ahh,’ laughed Miller, enjoying the contest as always. ‘I’ve found the answer – it’s a much better game for everyone if I aim at your bat!’

***

Nailing it

The post-war years were tough in England and only the leading players had sponsored bats. The rest had to buy their own.

Eric Hollies, a noted No. 11, would use a borrowed bat or any discards he could lay his hands on.

Against the visiting South Africans at Trent Bridge in 1947, he enjoyed his finest moments at the crease, sharing a match-saving 51-run last-wicket stand with Jack Martin, an amateur from Kent playing his one and only Test. It was found later that Eric’s bat had been held together by a two-inch nail!

Another time in a keenly fought county game against Notts and its expressman Bill Voce of Bodyline fame, Eric was pushing hopefully up the line with a fair degree of success when Voce tapped him on the shoulder at the end of an over. ‘Eric,’ he said, ‘You’ve got two choices: you can get out – or be carried out!’

Eric quickly discarded any thoughts of finishing with the ‘red inks’ and was soon back in the pavilion again.

See also: A go-slow

***

Straight talking

Charlie MacGill, Stuart’s grandfather, held the ball over the stumps with both South Australian batsmen Don Bradman and Ron Hamence stranded at the opposite end.

When he made no attempt to complete the run out and end what had been a rapid-fire 150-run stand, Hamence made a dash for the opposite crease, only for MacGill to knock the bails off with him halfway back.

‘What was all that about?’ asked Hamence. ‘You’ve cost me a century.’

‘They didn’t come here to watch you, Ronny,’ said MacGill.

***

The greatest exhibition of batting … ever

Walter Hammond will always be high in the pantheon of cricket’s superstar batsmen. He could score runs in his sleep.

Once during net practice on a green, underprepared wicket, against bowlers of the ilk of a young Tom Goddard, Reg Sinfield and Charlie Parker – all England players or England players-to-be – Hammond casually took block and simply slaughtered the bowling. Others before him who had found it so difficult watched on bedazzled as Hammond, beautifully balanced, played shot after shot.

A baseball bat was in the corner of the net and at the end of his knock, Hammond picked it up and continued his dominance. In protest Parker threw the ball pitcher-like at Hammond and he belted it so far no-one bothered to even look for it.

‘Gentlemen,’ said Parker, ‘today we have just witnessed the greatest exhibition of batting you will ever see in your lifetime – savour it and never forget it.’

SUPERLATIVE: Walter Hammond

***

Thanks for the firewood … but

Life after cricket was always busy for ex-Test captain Joe Darling, a father-of-twelve, a parliamentarian and a successful sheep and cattle farmer in the Tasmanian midlands.

In semi-retirement, Joe, his wife Alice and the younger kids lived for twenty years between-the-wars at historic Claremont House near Hobart. Joe’s daily fitness ritual well into his sixties was to chop wood for an hour after breakfast. For twenty years a wood stove was used continuously at the property and in winter, two and sometimes three rooms had wood fires burning continuously.

The firewood would be sent to Claremont by rail in eight-foot (2.4- metre) lengths. Joe would split the wood and the boys would barrow it.

Two of his eldest sons at Stonehenge, the family’s sheep farm, once sent their father a lorry-load of ready-to-go firewood sawn up in convenient two-foot (60-centimetre) lengths. While he appreciated the gesture, he asked that it not be sawed up in the future!

Darling, incidentally, remains one of the few Australian captains to have also possessed a full set of the cricketing bible Wisden.

MULTI-GIFTED: Joe Darling

***

Masterful

Bill Bowes was bowling against his Yorkshire teammate the great Herbert Sutcliffe in an MCC game at Lord’s. He bounced him early, as he liked to do and Sutcliffe just let the ball fly harmlessly through to the wicketkeeper. He was barely 50 at lunch before accelerating afterwards, regularly hitting Bowes’ bouncers to the backward square boundaries despite the presence of two outriders.

Asked by Bowes later if his early hesitancy to play the hook had been dictated by the higher bounce with the newer ball, Sutcliffe replied, ‘No, not that. I’ve worked it out very carefully and find I can score 40 runs off the bouncer to every once it gets me out. Forty runs for once out is not sufficient for me.

‘At the start of my innings I will only try to hit the bouncer where you have no fieldsmen. If you have a man at fine leg, I will hit any ball which I think can be hit to square leg. When I have got 40 runs or so on the board I’m prepared to back my ability to hit short of the fieldsmen, over their heads or between them. I’ll try and score off the lot. Forty runs for once out is then worth it.’

It’s little wonder Sutcliffe scored more than 50 000 first-class runs at an average of 50-plus with 150 centuries. Three times in consecutive innings in Australia he shared century stands with his famous opening partner Jack Hobbs (1924–25), and twice in the same Melbourne Test match batted through the entire day’s play. His overriding asset was his indomitable temperament. So poised and masterful was he that Bill O’Reilly once said of him, ‘Herbie was the very essence of combat and typified the English foe for whose dismissal was my major program for the day.’

DOYENS: Herbert Sutcliffe (left) at the end of his career with rising youngster Len Hutton

***

Pioneers of Test Match Special

Hedley Verity’s fourteen-wicket epic at Lord’s in 1934 is an integral in Ashes lore as it triggered a rare Australian defeat at the home of cricket. But it had a rival that very memorable June Monday. High up in the members, the BBC’s sole commentator Howard Marshall called the action one-out, virtually ball-by-ball, all day.

Interest in the cricket was at an all-time high and BBC listeners demanded more cricket and less music, giving Marshall barely a break but for the lunch and tea intervals. ‘The engineers were very helpful,’ he recalled years later. ‘They were always ready to fetch me a glass of beer or a cup of tea, or get the bowling figures from the [nearby] scorers. They couldn’t widdle for me though!’

From the next Test, the BBC appointed a scorer, Arthur Wrigley, for the princely sum of one pound per day and together Marshall and Wrigley formed the first great commentary duo, the forerunner to Aggers, Blowers and co. and the famed Test Match Special boys.

***

Few were as canny as the pocket-sized Atlas E H ‘Patsy’ Hendren whose joyous runmakings and contribution to English cricket stretched more than thirty years.

Even into his mid-forties, the little imp’s signature hook shot rivalled anyone in England.

Young Alf Gover was making his name as an emerging fast bowler for Surrey in the early ’30s and on the morning of a game at Lord’s, Patsy introduced himself to the young man, congratulating him on the career he’d had so far and then very quietly asked him not to pitch too short during the game. ‘I doon’tt see ’em as well as I used to,’ he said.

Hendren was at first drop and Gover’s first three deliveries were nice and full before he pitched short and saw it slammed to the square leg fence. The two made eye contact, Hendren shaking his head at the pace tyro. The next one was again short, this time over the off stump and Hendren backed away and flicked it to the third-man boundary. Gover took it as a ‘victory’. Hendren hadn’t wanted to get behind the ball. ‘Now he’s running away,’ he thought as he headed back to the top of his mark, before deciding to bowl one as short and as fast as he could straight at the veteran.

Hendren picked it up early and hit it for 6 high into the Mound Stand.

At the change of ends, Jack Hobbs approached Gover and asked, ‘Why are you bowling short at Patsy?’

‘He’s frightened of short bouncers.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘He did …’

***

The extraordinary Mr Gunn

Few could entertain like George Gunn whose flicks, wafts and caresses thrilled and inspired dozens of writers, including the greatest of all Neville Cardus. Long before the advent of the ramp shot or the reverse sweep, Gunn would toy with the bowling, squeezing yorkers for 4 with his deliberate draw shot which went between his legs.

Often he’d walk or even run at bowlers – even those with genuine pace like the famed Australian Ted McDonald.

At Old Trafford one day he skipped at McDonald who bowled short and Gunn deliberately lofted it high over third man for a majestic 6.

McDonald was unimpressed and delaying his walk back, said to Gunn, ‘George, get back to your crease or I’ll knock your head off,’ to which Gunn replied, ‘Ted … you couldn’t knock the skin off a rice pudding.’

Another time, Gunn began his characteristic walk at Cecil Parkin as ‘Cec’ gathered himself to bowl. Withholding the ball, Parkin continued down the wicket and asked, ‘Was theer summat you wanted to say to me, George?’

Gunn’s Ashes debut Down Under was truly extraordinary. He had been ill and went unselected in the original fourteen-man squad to Australia in 1907–08 under the captaincy of Arthur Jones, his county captain at Notts. It was agreed, however, that the warmer weather in Australia would be beneficial for his health. Gunn was asked if he would tour as the team’s scorer – and, if required, play an occasional ‘up-country’ game for an additional fee.

On the eve of the opening Test in Sydney, Jones fell ill and Gunn was named to take his place, ahead of a young Jack Hobbs – even though Gunn hadn’t played in any of the six lead-up games.

At breakfast that morning there were murmurings of discontent at Gunn’s shock elevation – Hobbs’ touring teammate Len Braund not-so-subtly suggesting that Gunn did not deserve to play.

Listed at No. 3, Gunn walked out to bat shortly after midday. So unknown was he that one of the Australians Charlie Macartney asked a teammate who this GUNN person was who’d just been listed on the SCG scoreboard.

From his first ball, which he hit for 4 through cover point, Gunn played with amazing polish and style. By mid-afternoon he’d made one of the great debut centuries of all. In a stand of 117 with Braund, Gunn’s share was 91.

Years later, author Basil Haynes said Gunn had told a neighbour about that first innings against Australia. ‘He [Braund] had as good as said I couldn’t bat,’ said Gunn.

‘So when he came out to join me I thought, “Well, we’ll have to see about that.” I had strike and I kept on taking singles at the end of each over. I reckon I kept him away from the bowling for about the first 45 minutes of his innings. After that he didn’t say much!’

Gunn made 119 and 74 on debut and appeared in all five Tests, topping the aggregate and the averages for both teams.

Amazingly, for one so gifted who made batting look so contemptuously easy, fourteen of his fifteen Tests were overseas, including his last at the age of fifty in the Caribbean in 1930 where he was described as ‘the man who walks down the wicket and tickles them where he likes’.

During this final tour in the field he would amuse himself when the two West Indian batsmen were conferring mid-pitch by creeping towards them, hand cocked to his ear, in pantomimic caution. The crowd would yell, ‘He’s coming … he hear you!’ And at that George would put a finger to his lips for silence and tiptoe stealthily away.

See also: Old habits

***

Staying mum

Yorkshireman Maurice Leyland, scorer of more than 30 000 first-class runs, was once asked his real opinion of fast bowling: ‘Nune of oos liik it, but some of oos don let on.’

***

Enter the Black Catapult

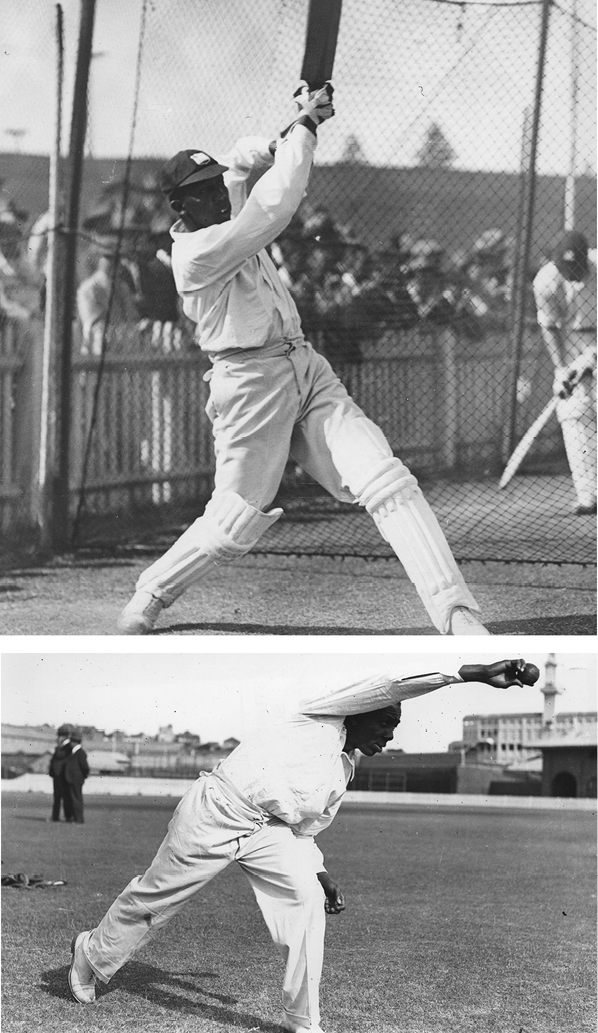

Learie Constantine became known as ‘the Black Catapult’ during his one and only visit to Australia with Jack Grant’s 1930–31 West Indians.

An exhilarating ‘three-in-one’ cricketer who bowled fast, hit hard and was dazzling in the field, Constantine made 147 at Newcastle before lunch.

Opposing the Aboriginal express Eddie Gilbert in Brisbane, Constantine swiped him for 6 over deep square leg and Gilbert responded by walking down the wicket and shaking Constantine’s hand. No-one had ever hit him for 6 before, he said.

Of Gilbert’s explosive pace from only six or seven paces, Constantine said, ‘He is the only fast bowler I have known who begins the over at a clinking good speed and gets faster every ball!’

In Sydney when ‘Conny’ took a tour-best six for 45 against New South Wales, he said he invariably bowled better when he’d lunched on pickles.

Australian crowds loved him and he loved them. ‘At Sydney,’ he said, ‘the crowd sits on the slopes without jackets, and with copious liquid refreshment and impartiality jeer at friends and foe alike. They make a terrific row but mean no harm. In fact I found that on the whole they had more to say to their own players than to us.’

His only regret from the entire tour came mid-series in Brisbane when Don Bradman was dropped by slipsman Lionel Birkett when he’d just come to the wicket. The Don went on to make 223.

SIMPLY ELECTRIFYING: Learie Constantine was a ‘three-in-one’ cricketer, a batsman of rare flair, furiously fast paceman and a fieldsman with athleticism, grace and power

***

Walking the plank

That inaugural West Indian tour in 1930–31 was eye-opening, the basically black team being captained by a white West Indian, the Cambridge educated Jack Grant who had not seen any of his teammates play before the first fixtures.

A hailstorm in Sydney which converted the ground from lush green to snowy white in a matter of minutes stunned the men from the sunny Caribbean. They also had their wallets rifled in Sydney.

Aside from the cricket, which saw the team beaten 4–1, they also had the opportunity to visit the famous Sydney Harbour Bridge, which officially opened in 1931.

The two arches had not yet met in the middle and Grant and his team were invited to walk from one side to the other via a single six-foot (1.8-metre) plank.

‘Some in the team refused to make the crossing,’ said Grant, ‘and I had every sympathy for them for the water below seemed far away. Moreover it seemed to have some magnetic attraction. It was frightening … yet I took the risk and crossed over and back – still alive to tell the tale.’

***

No accidental hero

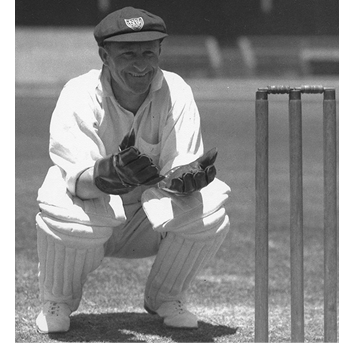

One of the golden rules at Bert Oldfield’s Sports Store in Hunter Street was that any ball, from cricket and golf to tennis and squash, had to be thrown at him so he could maintain and hone the reflexes that made him Australia’s most successful between-the-wars wicketkeeper.

Employees would throw golf clubs down a light shaft, rather than use the lift, so Bert could catch them. He always walked the two miles from work to the Sydney Cricket Ground, and at a brisk rate carrying his cricket case. To avoid the risk of straining his eyes, he never read the newspapers or went to the cinema – cricket and keeping wickets was everything for him.

The first of five tours to England was in 1919 with the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) side when he first kept wickets to Jack Gregory. He retired with a record fifty-two Test stumpings including his signature stumping of Jack Hobbs from Clarrie Grimmett’s bowling in Sydney in 1924–25, the dismissal of his career.

ENDURING: The much-loved Bert Oldfield in his favourite baggy blue NSW cap

***

Rocket science

Spare pads were at a premium during a village match in Yorkshire, so much so that the opposing team had only one pad for each of its batsmen.

In cases like this, right-hand batsmen generally strap the pad onto their left leg as it is the one facing the bowler.

This day the batsman came in with his pad on the right leg so the fielding team naturally assumed he was a left-hander and changed over.

But the batsman shaped up as a rightie. ‘You’ve got your pad on the wrong leg,’ said one fielder.

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I thought I was batting at the other end!’

***

My lucky day

Cecil Parkin, one of cricket’s greatest characters, was batting with fellow Lancastrian Dick Tyldesley at Lord’s when he called for a quick run. ‘No,’ said Dick, without moving from his crease. But Cec kept running and was within handshake distance of his partner when Middlesex’s young Jack Hearne, who only had to walk to the wicket to break it, instead decided on one almighty, full-gusto fling from close range, missed everything and watched helplessly as the ball rocketed to the third man boundary for 4. Delighted at his sudden good fortune, Cec shouldered his bat like a rifle and marched back down the twenty-two yards singing ‘The British Grenadiers’.

***

He played into his mid-fifties

One of the secrets of evergreen Sammy Carter’s longevity was his daily dip at Bondi beach, summer and winter, 365 days a year. An international well into his fifties, Carter played in his final tour at the age of fifty-four, in America and Canada with Vic Richardson’s 1932 Australians. Even with debilitating arthritis, he kept wickets in most of the fifty-plus games crammed into just two months.

As an Australian Test player of note, Carter was renowned for dragging his bat along the ground behind him while walking to the wicket. He also possessed an extraordinary ‘scoop’ shot which he’d use against even the fast bowlers, lifting full-length balls on the leg stump over his left shoulder and to the fine-leg fence … shades of Twenty20 cricket a century before it was invented.

An undertaker by trade, he was a stickler for time and rules and was responsible at Manchester for pointing out to his captain Warwick Armstrong that the Hon. Lionel Tennyson was acting outside the laws when he tried to declare his team’s innings closed late on the second day after the opening day of the Test had been washed out. England had to bat on.

During the ’32 tour, Carter predicted that the team’s young wrist spinner Chuck Fleetwood-Smith would one day win a Test match for Australia. And he did, in Adelaide in 1937 when he took the prize wicket of England’s No. 1 Walter Hammond on the final morning.

***

The supreme master

Even at forty-two, England’s Jack Hobbs was the game’s supreme master, starting the 1924–25 Ashes summer with centuries in the first three Tests against a formidable Australian attack, including famed expressman Jack Gregory and wrist spinner Arthur Mailey.

Mailey’s extravagant blend of highly flung leg breaks and googlies rarely ruffled Hobbs, who’d wait for an overpitch or a shorter one and stroke the ball basically wherever he wanted.

Leading into the Tests, Mailey worked long hours on a second, better disguised googly. He refused to use it in the state match against the tourists, even though Hobbs got into his 80s. He wanted it to be a shock for the first Test in Sydney.

Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe were into an immediate stride and Mailey was called upon early. For the first three overs he bowled nothing but leggies and his traditional, familiar googly. Come the start of his fourth over, Mailey decided to use his new shock ball.

‘This will get Jack thinking,’ said Mailey to himself at the top of his run-up.

In he came, intent on a big back-of-the-hand flick. He had visions of leaving the great man stranded. But almost as the ball was leaving his hand, Hobbs called, ‘Googly Arthur!’ and slapped it with the spin through to the mid-wicket boundary!

***

Devil breaks

Australia’s first great leg spinner H V Hordern would be even more feted today had he not started Test cricket so late, aged twenty-seven. His dentistry studies took him to the University of Philadelphia at a time when he could easily have been playing Test cricket. While his career was limited to just seven Tests (for forty-six wickets) he was accorded one of the great nicknames, ‘the Googlyman’ when touring Jamaica with the Gents of Philadelphia. Awestruck locals truly believed his each-way mystery spin gave him an allegiance to the Devil.

***

A game for gentlemen

‘Take them away Joe,’ said the aristocratic Archie MacLaren eyeing two close catchers on the leg side at the start of a Test in Sydney. ‘These men, positioned here, are likely to impede the execution of my hook shot. They are of no use to you.’

Joe Darling, Australia’s captain declined and called for his fast bowler Ernie Jones to proceed.

However, after several well-pitched deliveries were driven straight for 4s, Darling withdrew one of the short legs and placed him on the drive.

‘Thank you, Joe,’ said MacLaren, ‘now we can proceed with this match like gentlemen.’