-

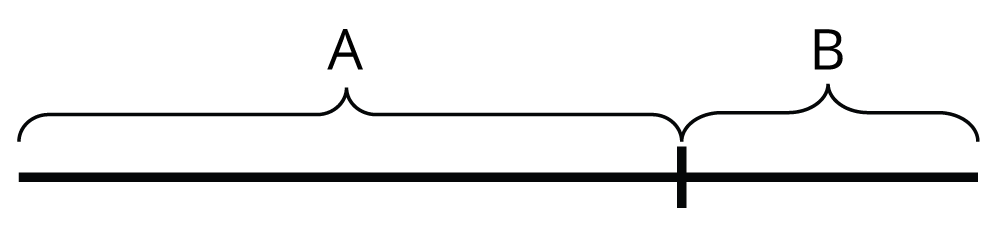

In math, simple relationships can often take on critical roles. One such relationship, the Golden Ratio, has captivated the imagination and appealed to mathematicians, architects, astronomers, and philosophers alike. The Golden Ratio has perhaps had more of an effect on civilization than any other well-known mathematical constant. To best understand the concept, start with a line and cut it into two pieces (as seen in the figure). If the pieces are cut according to the Golden Ratio, then the ratio of the length of the longer piece to the length of the shorter piece (A : B) would be the same as the ratio of the length of the entire line to the length of the longer piece (A+B : A). Rounded to the nearest thousandth, both of these ratios will equal 1.618 : 1.

The first recorded exploration of the Golden Ratio comes from the Greek mathematician Euclid in his 13-volume treatise on mathematics, Elements, published in approximately 300 BC. Many other mathematicians since Euclid have studied the ratio. It appears in various elements of certain “regular” geometric figures, which are geometric figures with all side lengths equal to each other and all internal angles equal to each other. Other regular or nearly regular figures that feature the ratio include the pentagram (a five-sided star formed by five crossing line segments, the center of which is a regular pentagon) and three-dimensional solids such as the dodecahedron (whose 12 faces are all regular pentagons).

The Fibonacci sequence, described by Leonardo Fibonacci, demonstrates one application of the Golden Ratio. The Fibonacci sequence is defined such that each term in the sequence is the sum of the previous two terms, where the first two terms are 0 and 1. The next term would be 0 + 1 = 1, followed by 1 + 1 = 2, 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, etc. This sequence continues: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, and so on. As the sequence progresses, the ratio of any number in the sequence to the previous number gets closer to the Golden Ratio. This sequence appears repeatedly in various applications in mathematics.

The allure of the Golden Ratio is not limited to mathematics, however. Many experts believe that its aesthetic appeal may have been appreciated before it was ever described mathematically. In fact, ample evidence suggests that many design elements of the Parthenon building in ancient Greece bear a relationship to the Golden Ratio. Regular pentagons, pentagrams, and decagons were all used as design elements in its construction. In addition, several elements of the façade of the building incorporate the Golden Rectangle, whose length and width are in proportion to the Golden Ratio. Since the Parthenon was built over a century before Elements was published, the visual attractiveness of the ratio, at least for the building’s designers, may have played a role in the building’s engineering and construction.

Numerous studies indicate that many pieces of art now considered masterpieces may also have incorporated the Golden Ratio in some way. Leonardo da Vinci created drawings illustrating the Golden Ratio in numerous forms to supplement the writing of De Divina Proportione. This book on mathematics, written by Luca Pacioli, explored the application of various ratios, especially the Golden Ratio, in geometry and art. Analysts believe that the Golden Ratio influenced proportions in some of da Vinci’s other works, including his Mona Lisa and Annunciation paintings. The ratio is also evident in certain elements of paintings by Raphael and Michelangelo. Swiss painter and architect Le Corbusier used the Golden Ratio in many design components of his paintings and buildings. Finally, Salvador Dalí intentionally made the dimensions of his work Sacrament of the Last Supper exactly equal to the Golden Ratio, and incorporated a large dodecahedron as a design element in the painting’s background.

The Golden Ratio even appears in numerous aspects of nature. Philosopher Adolf Zeising observed that it was a frequently occurring relation in the geometry of natural crystal shapes. He also discovered a common recurrence of the ratio in the arrangement of branches and leaves on the stems of many forms of plant life. Indeed, the Golden Spiral, formed by drawing a smooth curve connecting the corners of Golden Rectangles repeatedly inscribed inside one another, approximates the arrangement or growth of many plant leaves and seeds, mollusk shells, and spiral galaxies.

-

Now answer the questions.

-

-

P1 Paragraph 1 S1 In math, simple relationships can often take on critical roles. 2 One such relationship, the Golden Ratio, has captivated the imagination and appealed to mathematicians, architects, astronomers, and philosophers alike. 3 The Golden Ratio has perhaps had more of an effect on civilization than any other well-known mathematical constant. 4 To best understand the concept, start with a line and cut it into two pieces (as seen in the figure).

5 If the pieces are cut according to the Golden Ratio, then the ratio of the length of the longer piece to the length of the shorter piece (A : B) would be the same as the ratio of the length of the entire line to the length of the longer piece (A+B : A).

6 Rounded to the nearest thousandth, both of these ratios will equal 1.618 : 1.

-

According to paragraph 1, which of the following is true about the Golden Ratio?

- It was invented by mathematicians.

- It has significantly impacted society in general.

- It is most useful to astronomers and philosophers.

- It is used to accurately calculate a length.

-

The phrase “appealed to” in the passage is closest in meaning to

- interested

- defended

- requested

- repulsed

-

-

P2 Paragraph 2 S1 The first recorded exploration of the Golden Ratio comes from the Greek mathematician Euclid in his 13-volume treatise on mathematics, Elements, published in approximately 300 BC. 2 Many other mathematicians since Euclid have studied the ratio. 3 It appears in various elements related to certain “regular” geometric figures, which are geometric figures with all side lengths equal to each other and all internal angles equal to each other.

4 Other regular or nearly regular figures that feature the ratio include the pentagram (a five-sided star formed by five crossing line segments, the center of which is a regular pentagon) and three-dimensional solids such as the dodecahedron (whose 12 faces are all regular pentagons). -

According to paragraph 2, all of the following are true of the Golden Ratio EXCEPT:

- Its first known description occurred in approximately 300 BC.

- It was studied by mathematicians after Euclid.

- It only occurs in regular geometric figures.

- It appears in some three-dimensional geometric figures.

-

-

P3 Paragraph 3 S1 The Fibonacci sequence, described by Leonardo Fibonacci, demonstrates one application of the Golden Ratio. 2 The Fibonacci sequence is defined such that each term in the sequence is the sum of the previous two terms, where the first two terms are 0 and 1. 3 The next term would be 0 + 1 = 1, followed by 1 + 1 = 2, 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, etc. 4 This sequence continues: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, and so on. 5 As the sequence progresses, the ratio of any number in the sequence to the previous number gets closer to the Golden Ratio. 6 This sequence appears repeatedly in various applications in mathematics. -

According to paragraph 3, which of the following is true about the Fibonacci sequence?

- It can be used to estimate the Golden Ratio.

- It cannot be computed without the use of the Golden Ratio.

- It was discovered by Euclid in approximately 300 BC.

- No two terms in the sequence are equal to one another.

-

The word “progresses” in the passage is closest in meaning to

- calculates

- declines

- continues

- disintegrates

-

-

-

P4 Paragraph 4 S1 The allure of the Golden Ratio is not limited to mathematics, however. 2 Many experts believe that its aesthetic appeal may have been appreciated before it was ever described mathematically. 3 In fact, ample evidence suggests that many design elements of the Parthenon building in ancient Greece bear a relationship to the Golden Ratio. 4 Regular pentagons, pentagrams, and decagons were all used as design elements in its construction. 5 In addition, several elements of the façade of the building incorporate the Golden Rectangle, whose length and width are in proportion to the Golden Ratio. 6 Since the Parthenon was built over a century before Elements was published, the visual attractiveness of the ratio, at least for the building’s designers, may have played a role in the building’s engineering and construction. -

According to paragraph 4, which of the following is true about the construction of the Parthenon?

- It was based upon the writings of Euclid.

- Aesthetics may have played a role in the Parthenon’s use of elements that exhibit the Golden Ratio.

- It is an example of mathematics being prioritized over aesthetics.

- The designer of the Parthenon is unknown.

-

Paragraph 4 supports the idea that the designers of the Parthenon

- were able to derive the Golden Ratio mathematically before it was formally recorded by Euclid

- were aware of the Golden Ratio on some level, even if they could not formally define it

- were mathematicians

- were more interested in aesthetic concerns than sound architectural principles

-

The word “elements” in the passage is closest in meaning to

- origins

- substances

- drawings

- components

-

-

-

P5 Paragraph 5 S1 Numerous studies indicate that many pieces of art now considered masterpieces may also have incorporated the Golden Ratio in some way. 2 Leonardo da Vinci created drawings illustrating the Golden Ratio in numerous forms to supplement the writing of De Divina Proportione. 3 This book on mathematics, written by Luca Pacioli, explored the application of various ratios, especially the Golden Ratio, in geometry and art. 4 Analysts believe that the Golden Ratio influenced proportions in some of da Vinci’s other works, including his Mona Lisa and Annunciation paintings. 5 The ratio is also evident in certain elements of paintings by Raphael and Michelangelo. 6 Swiss painter and architect Le Corbusier used the Golden Ratio in many design components of his paintings and buildings. 7 Finally, Salvador Dalí intentionally made the dimensions of his work Sacrament of the Last Supper exactly equal to the Golden Ratio, and incorporated a large dodecahedron as a design element in the painting’s background.

-

Why does the author mention that Dalí “incorporated a large dodecahedron as a design element in the painting’s background”?

- To demonstrate Dalí’s frequent use of geometric shapes

- To illustrate the extent to which the Golden Ratio has influenced some works of art

- To argue that certain style elements in art are more effective than others

- To refer to works by other artists such as da Vinci and Le Corbusier

-

According to paragraph 5, da Vinci’s illustrations in De Divina Proportione and two of his paintings, the Mona Lisa and Annunciation,

- exhibit evidence that da Vinci’s work was influenced by the Golden Ratio

- illustrate that he had a higher commitment to the Golden Ratio than other artists

- provide examples showing that Renaissance art was more influenced by the Golden Ratio than modern art

- demonstrate that da Vinci’s work was at least as influential as the work of mathematicians or architects

-

-

-

P6 Paragraph 6 S1 The Golden Ratio even appears in numerous aspects of nature. 2 Philosopher Adolf Zeising observed that it was a frequently occurring relation in the geometry of natural crystal shapes. 3 He also discovered a common recurrence of the ratio in the arrangement of branches and leaves on the stems of many forms of plant life. 4 Indeed, the Golden Spiral, formed by drawing a smooth curve connecting the corners of Golden Rectangles repeatedly inscribed inside one another, approximates the arrangement or growth of many plant leaves and seeds, mollusk shells, and spiral galaxies. -

By including the text “formed by drawing a smooth curve connecting the corners of Golden Rectangles repeatedly inscribed inside one another,” the author is

- emphasizing the importance of the Golden Spiral

- providing the reader with instructions for creating a Golden Spiral

- defining the Golden Spiral in relation to the Golden Ratio

- providing illustrations of elements in nature that exhibit the Golden Ratio

-

According to paragraph 6, which of the following is an example from nature that demonstrates the Golden Spiral?

- The arrangement of branches in some forms of plant life

- The common recurrence of the spiral throughout nature

- The geometry of natural crystal shapes

- The arrangement or growth of some galaxies

-

-

P3

Paragraph 3 S1 The Fibonacci sequence, described by Leonardo Fibonacci, demonstrates one application of the Golden Ratio. 2–4 A The Fibonacci sequence is defined such that each term in the sequence is the sum of the previous two terms, where the first two terms are 0 and 1. The next term would be 0 + 1 = 1, followed by 1 + 1 = 2, 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, etc. This sequence continues: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, and so on. 5 B As the sequence progresses, the ratio of any number in the sequence to the previous number gets closer to the Golden Ratio. 6 C This sequence appears repeatedly in various applications in mathematics. End D

Look at the part of the passage that is displayed above. The letters [A], [B], [C], and [D] indicate where the following sentence could be added.

-

For example, it can be shown that the sum of the entries in consecutive diagonals of Pascal’s triangle, useful in calculating binomial coefficients and probabilities, correspond to consecutive terms in the Fibonacci sequence.

Where would the sentence best fit?- Choice A

- Choice B

- Choice C

- Choice D

An introductory sentence for a brief summary of the passage is provided below. Complete the summary by selecting the THREE answer choices that express the most important ideas in the passage. Some sentences do not belong in the summary because they express ideas that are not presented in the passage or are minor ideas in the passage. This question is worth 2 points.

-

The Golden Ratio, a mathematical relationship that has been known for centuries, has numerous applications and associated examples in the fields of mathematics, architecture, art, and nature.

- The Fibonacci sequence has numerous applications in the field of mathematics.

- The Golden Ratio appears in mathematical sequences and regular geometrical figures.

- Some crystals have configurations that exhibit a relationship to the Golden Ratio.

- The Golden Ratio influenced the work of many famous artists, including Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Le Corbusier, and Dalí.

- The Golden Ratio appears in many examples from nature, ranging from crystal formations and plant structures to the shape of mollusk shells and spiral galaxies.

- Although described by Euclid in approximately 300 BC, the Golden Ratio was formally defined at a much earlier date.