3

DISPENSING AND DISPENSING WITH JUSTICE IN A GUERRILLA WAR

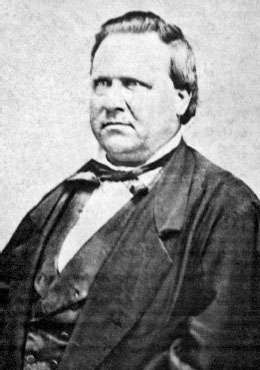

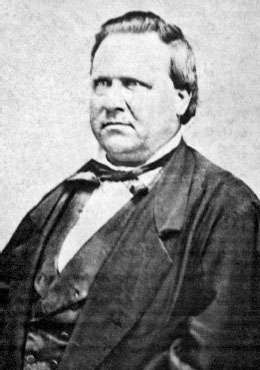

In 1859 Jefferson Jones, a prominent lawyer, completed his dream home in northern Callaway County. He lived with his wife and nine children (three of whom were named Southwest, Northeast and Octave) in a two-story Southern-style plantation house with a cupola from which the 250-pound Jones—newspapers called him “our ponderous friend”—could survey his farm and twenty slaves. Jones favored secession but failed in his bid for election to the 1861 convention called by Governor Jackson.

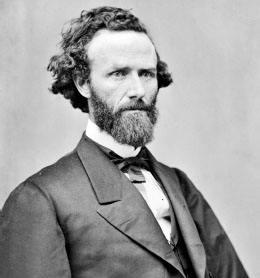

In October 1861, Jones was alerted by a local minuteman group known as the “A to Z’s” that Union Home Guards under John B. Henderson (later a United States senator and co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment) had arrived in Callaway County and were arresting suspected Secessionists. Many of those who escaped arrest gathered in the center of the county and elected Jefferson Jones as their colonel. Jones later claimed that he and his men “did not belong to army of the Southern Confederacy & did not desire to belong but that rather than yield our constitutional rights, we were determined to yield our lives.” Realizing that his rabble was no match even for the poorly equipped Home Guards, Jones met with Henderson to reach a truce. Their agreement—later called a “treaty” by Southern enthusiasts—provided that Jones’s men would disband in return for a promise that Henderson would respect their constitutional rights. Jones said that he met with General John Schofield, the local Union commander several times, and that Schofield approved the agreement with Henderson. This agreement would later be the basis for the claim that the Union recognized the “Kingdom of Callaway.”

Jefferson Jones negotiated an agreement with John Henderson that became the basis for the legend of the Kingdom of Callaway. Kingdom of Callaway Historical Society.

Had matters ended there, Jones might have had a much less turbulent Civil War. But Jones was unable to restrain his opposition to Union forces whom he regarded, along with many Secessionist sympathizers, as invaders. General Sterling Price issued orders in December 1861 that an attack should be made on the North Missouri Railroad. Among the leaders of the Rebel forces was a Lieutenant Jamison, Jones’s nephew. Their task was to burn the railroad’s bridges and tear up its track. They met at Jones’s farm on December 20. Union forces got wind of the attack and deployed troops to prevent it. They were not entirely successful, as the Rebels did $160,000 in damages in destroying bridges, buildings and track. But the Federals were more successful in capturing the culprits.

Senator John B. Henderson, an early advocate of gradual emancipation, played a key role in the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment. Library of Congress.

Although Jones himself did not participate in the raid, he was arrested and charged with aiding and abetting the destruction of the railroad, aiding and abetting insurrection and acting as a spy and holding unlawful communications with the enemy. He sat in jail for a month and was finally released on January 27, 1862, upon posting a bond. While he was confined, Union soldiers—Jayhawkers, Jones claimed—burned the mill on his property, insulted his family and stole his wagons, horses and mules, their saddles, blankets, chains and other equipment. The soldiers also took five bolts of “negro shirting” that left his slaves without new clothes for the winter. Jones put all of these complaints into a letter to General Schofield, whom he apparently regarded as some sort of champion to whom he could appeal. Jones was mistaken. Schofield replied coldly that he had “no doubt you have suffered much inconvenience” but that all he would be made to suffer “will fall short of atoning for the misery caused by you not only to Union men but to the misguided dupes who have yielded to your baneful influence,” the “evil effect” of which “can hardly be counterbalanced by the loss of a few wagons and horses.” Schofield nevertheless promised Jones a fair trial and said, “I should be gratified if you are found less guilty than I believe you to be.”

Later that year, Jones got his trial before a military commission sitting in Danville. Jones provided a skillful defense. Even the captured guerrillas who testified against him conceded that he told them he did not want men there who might lead to his arrest. Jones explained that a large cache of who and ammunition found at his home was purchased in bulk so that he would not have to be “piddling so often with the stores.” Jones asserted that he respected the agreement with Henderson and had not taken up arms against the government and had not willingly cooperated with the Rebels. He was acquitted on all charges. But apparently reflecting the unproven suspicions surrounding his conduct, Jones was required to sign an oath of allegiance and to post a $10,000 bond to secure “future good conduct.”

For the moment, Jones escaped the wrath of Federal justice. But he was far from disentangled from it. In 1863, a Unionist neighbor, Dr. James Martien, wrote to Union authorities requesting that they investigate Jones for renewed secessionist activities. A Union scout, William Poillon, gathered evidence that Jones had secretly supported Confederate recruiter Colonel Joseph Porter and the notorious guerrilla Alvin Cobb the prior year. Jones asserted that Dr. Martien had a personal grudge because Jones had successfully sued him for unpaid attorney’s fees and because Jones’s father-in-law had obtained a writ against Martien for return of a slave who had run away. The authorities found that Jones had violated his bond and who a sale of his property. Jones’s friends tore down the signs and prevented any sale. Major Daniel Draper, the local commander, wrote that “Rebels and rebel sympathizers all through the country are to-day rejoicing.” Rather surprisingly, Federal officials allowed Jones to leave Missouri in 1864 to visit several states in the East and Midwest to buy sheep for his farm. Upon his return, Jones was accused of spying and belonging to a “secret agency.” Once again, Jones was jailed. He became ill and reportedly lost nearly one hundred pounds. He remained in confinement until released in 1865.

The experience of Jefferson Jones was not uncommon. Many of those captured in December 1861 were brought before military commissions charged not only with bridge burning but also with violations of the laws of war and even treason. The legal basis for these charges was shaky. Certainly, they burned bridges, but railroad bridges were a legitimate military target, and many defendants asserted that they had done so under orders from General Price. These pleas went nowhere despite evidence produced by some defendants of their military commissions from Rebel forces. The defense appears to have failed because they were not formally mustered into Confederate service and lacked uniforms—a most peculiar rationale given that most of the Confederate army in Missouri had no uniforms either. And treason is an offense whose elements and standard of proof is specifically defined in the Constitution. Even Halleck, who otherwise approved of military commissions, drew the line at allowing military tribunals to hear charges of treason because such crimes were properly for the civil courts.

Two parts of Frémont’s August 30 proclamation were not modified by Lincoln: the plan to give military authorities the power to try civilians for violations of existing laws and to “supply such deficiencies as the conditions of war demand” and the declaration of martial law throughout the state. The establishment of military commissions found its precedent in the Mexican War. During that conflict, General Winfield Scott found that the occupying forces of the United States Army—particularly, in his view, the volunteers—were committing what would otherwise be deemed crimes under civil law, such as murder, rape and robbery of Mexican civilians, but they were not subject to punishment by military law. Accordingly, he devised a system of military commissions to try these offenses, primarily committed by his own troops. His actions shocked his superiors, but they did nothing to stop him. In 1861, his innovation was adapted to a civil war.

The first commissions began to try defendants in September 1861 and continued even after the war was over. Military commissions were active throughout the United States, even in states as far away from the active conflict as Massachusetts (site of Fort Warren in Boston) and Wisconsin (where, albeit, only one such trial was held). Missouri had the most trials by military commissions by a comfortable margin. Mark Neely found there were 4,271 trials by military commissions. Of these, the location of the trial could be determined in 4,203 cases—and of these, 1,940, or 46.2 percent, were held in Missouri.

Nonetheless, conviction was not a foregone conclusion, as Jefferson Jones’s case demonstrated. After an early acquittal rate of 15 percent, the rate of “not guilty” verdicts in Missouri plummeted to only 4 percent. All of the verdicts were reviewed by higher authorities (Lincoln, as noted above, insisted on reviewing all death sentences), and the sentences were frequently mitigated to imprisonment, a lesser term of imprisonment or a fine.

Officers reviewing commission proceedings insisted that they follow procedures for courts-martial under the Articles of War. For example, the commission had to consist of at least three officers, there had to be an officer designated as the judge advocate to prosecute the case and proceedings had to be recorded. Indeed, the records of the military commissions were, in many instances, more complete than civil criminal trials in many states. The failure to swear the commission “in the presence of the accused” or the failure of the record to indicate that it had been done, was sufficient error to require reversal. Some of the charges were thrown out as too “informal” because volunteer or militia officers drawing them up failed to follow court-martial form, which required them to consist of two parts: the charge describing the offense and at least one specification detailing the facts supporting the charge, i.e., “the act, time, place and circumstance.” In some cases, the commission found the defendant guilty of the charge but not the specification, which rendered the conviction void because without a guilty verdict on the underlying facts the accused could not be guilty of the offense.

The accused was entitled to counsel of his or her choice, at least within limits. Isaac Snedecor, a Union officer, named his cousin, none other than Jefferson Jones, as a witness for his trial. But authorities found out that was merely a pretext under which Jones was secretly providing legal counsel to Snedecor, and prohibited Jones from further participation in the proceedings. The defendant’s attorney, consistent with court-martial practice of the time, could not question or cross examine witnesses—that could be done only by the accused—but he was allowed to be present, offer advice and provide legal briefs or memoranda the accused could submit to the commission. (Snedecor, incidentally, was acquitted. The trial was so poorly conducted—not a single witness had any pertinent knowledge of the charges—that the department judge advocate scolded those involved for their inadequate preparation and complained that “due inquiry would have disclosed this and prevent the necessity of arraignment of the prisoner.”)

The commissions were not supposed to accept affidavits in lieu of live testimony. The defendant was allowed to have witnesses produced. This requirement sometimes resulted in long delays or adjournment of the proceedings because the witnesses were not available (military witnesses may be on duty in remote areas of the state) or had to travel from their homes to the place of trial.

The offenses tried by military commissions usually involved men charged with participating in guerrilla activities, including murder, burning of homes, looting or attack on Union soldiers, but even seemingly innocuous activities could bring a person before a commission to face drastic punishment. Neely cites the cases of James Sullivan and Elbert Rankin, who were found guilty of disloyal conduct. Sullivan had proclaimed, “I am a Jeff Davis man,” and Rankin had said “I am a Rebel” and took payment for a mule in Confederate money. Even writing to a loved one could be a crime under military law. James Jackson was convicted of writing his son, a soldier in the Confederate army. His sentence was reduced to the posting of a bond because the reviewing officer found him to be of advanced age and ignorant of military law in such instances.

Military commissions handed down punishments ranging from death sentences to imprisonment, banishment or, as in the case of James Jackson, the posting of a bond. The death sentences were reserved for suspected guerrillas who were convicted of the most serious offenses. The commission’s sentence was reviewed by departmental judge advocates and the departmental commanders. In many cases, they reduced the death penalty to imprisonment. Those that were not reduced were referred to Washington, where the case was reviewed by the army’s judge advocate general, Joseph Holt, and ultimately President Lincoln. Records show that 210 cases were submitted to Lincoln, of which 184 show the action he took. Overall, Lincoln approved the sentence in 90 cases and mitigated it in 94 cases.

One of the first measures the Union military used to try to control guerrilla attacks without the use of force was assessments against known or suspected Southern sympathizers. Assessments were simply confiscation of property. There was no legal basis for such actions, although it differed only in degree from “foraging,” a practice used by both armies to appropriate supplies from civilians under the rubric of military necessity. The theory behind assessments was that they would discourage disloyal citizens from providing help to guerrillas or Confederate forces because of the threat that their property would be seized and sold. It did not involve outright violence other than, of course, the force necessary to take the property.

General John Pope introduced the use of assessments in the summer of 1861 to stop what he called “wanton destruction” of railroad bridges. Pope issued a notice that he would hold the inhabitants of towns and villages within five miles of any destruction financially accountable unless they could provide “conclusive proof of active resistance” or “immediate information…giving names and details” to the army. He followed up with an order directing that each county seat and town appoint “the leading State-rights men (secessionists)…to serve on committees of safety against their will, and their property…made responsible for any violence or breach of peace committed by their friends.”

Although the order was intended to protect the railroads from guerrilla depredations, even railroad officials opposed it. J.T.K. Hayward, president of the Hannibal & St. Joseph, wrote to his superiors in Boston that “if we cannot have a change in the administration of military affairs here in North Missouri our cause will be ruined.” A prominent lawyer from Palmyra added his warning that Pope’s assessments were “exceedingly hurtful to the Union cause, in that, it gives color to the clamor of secessionists that the government is oppressive and that the purpose of the war is subjugation of the state and the South.”

Citizens did their best to avoid being named to one of the committees. William “Uncle Billy” Martin, an ardent and wealthy secessionist from Audrain County, sought help from his friend Isaac Sturgeon. Sturgeon was not only the Unionist president of the North Missouri Railroad, but he was also married to Pope’s niece. Together they went to see Pope at his headquarters in Mexico, Missouri. Sturgeon, however, failed to back up Martin’s plea to be let off the committee, pointing out to Pope that “if I had a matter I wanted well attended to, Uncle Billy would be the man I would select.” Martin was heard to mutter as he left, “I never imagined I would be an officeholder under Abe Lincoln.” Shortly afterward, Frémont, bowing to pressure from Unionists and railroad officials, intervened to disband the committees.

Pope’s less than satisfactory experience with assessments did not deter Federal commanders from using them again. In late 1861, St. Louis was flooded with refugees, mostly fleeing from the Confederate forces in Southwest Missouri—perhaps as many as forty thousand men, women and children, both white and black. The new commander in Missouri, Henry Halleck, wrote: “Men, women and children have alike been stripped and plundered. Thousands of such persons are finding their way to this city barefooted, half clad, and in a destitute and starving condition.”

William “Uncle Billy” Martin unsuccessfully tried to avoid serving on General John Pope’s committee of public safety. From Herschel Schooley, Centennial History of Audrain County.

On December 12, Halleck issued General Order No. 24, which provided for the assessment of persons to pay for the cost of feeding, clothing and housing the refugees. Some three hundred persons were named as being subject to the levy. On Christmas Eve, the first assessments were issued to sixty persons. A few protested their loyalty and appealed. Others were defiant and “declared that they would see their houses burned over their heads before paying one cent.”

In response to the complaints, Halleck appointed a new board of assessors. The board assessed a total of $16,340 against St. Louis citizens—over their renewed protests. Franklin Dick, one of the assessors, wrote in his journal that the targets of the assessments “neither appeal nor pay. I am inclined to think that Genl. Halleck will have to resort to Extreme measures with them.” A week later, he wrote that Union authorities were “seizing the chattels of the assessed Traitors in the City & they are howling in suppressed tones.”

Samuel Engler sought redress in the civil courts. He obtained a court order directing that the provost marshal return twenty-nine boxes of Admantine candles and fifty-one boxes of Star candles. He took Sheriff John Andrews with him to serve the writ and regain possession of his property. The guard refused. The local paper reported: “The Sheriff concluded that his duty did not require him to be absolutely riddled with Minié balls and to sacrifice the lives of his undisciplined corps, and therefore gracefully ordered a retreat.” Andrews’s return on the writ was less colorful but succinct: he failed to execute the court order because of “an armed body of men purporting to act under the authority of the United States which force it was not possible for me to resist or overcome.”

Halleck reacted immediately to Engler’s presumption by arresting him and his attorney. Dick gleefully reported that an armed guard escorted Engler out of town. After posting a bond, Engler was allowed to return to St. Louis later in the year. But he was banished in May 1863 for making disloyal statements.

In February 1862, the authorities auctioned the seized goods. The St. Louis Republican described the scene:

An immense crowd, more than could obtain entrance, was present yesterday morning, and only those who went early could secure places inside. So great was the rush, that it was found necessary to detail a squad of soldiers to keep the sidewalks clear and preserve an open ingress and egress.

A large number of ladies were present, and many having been wedged in by the throng, found it difficult to extricate themselves when they wished, and were compelled to stand upon the wet and sloppy floor—a situation the reverse of comfortable. Some secession sympathizers found their way into the rooms, and by a variety of sneers and mutterings, bid fair at times to interrupt “the perfect harmony of the occasion”; but, as a usual thing, there was less disorder and confusion than might have been expected.

As a general thing, considering the times, the furniture, &c., brought fair prices, though in some instances great bargains were had. An elegant piano, nearly new, said to have cost Mr. KAYSER between $500 and $600 in Europe, was sold for $240. Another, for which Mr. POLK is reputed to have given over a $1,000, went for $330. A set of brocatel rosewood furniture, (sofa, arm chairs, and fancy chairs,) owned by Mr. PARK, brought $145. A lot of miscellaneous books, one hundred and ten in number, the property of Mr. FUNKHOUSER, netted about $29. Some of the line carpets, velvet and Brussels, were sold low, while others brought full retail prices.

The provost marshal, in a show of punctiliousness, found that Engler’s property sold for more than he owed, and refunded him $4.97. But any apparent fairness in the auction did not mollify critics of the assessment process. Dick noted in his diary that

I have contracted additional hate from these bloody Traitors here by acting on this [assessment] Comm. & our weak knee’d Union people shake their heads at it…In St. Louis, I feel that we have in our midst a damnable, wicked & treacherous set of bloodhounds—their hatred at me for being on the Asst. Commission is deep & exasperated—and I feel pointedly the stupid weakness of Congress in permitting these Traitors to remain openly defiant & hostile here, where they do so much injury.

The moderate success of the assessments in St. Louis in paying for refugee relief encouraged General John Schofield and Governor Gamble to resort to them later to finance the Enrolled Missouri Militia (EMM). They created the EMM to provide additional troops to fight guerrillas. Gamble agreed to pay EMM soldiers while they were on active duty, although they were subject to Federal army control. But the state had little money to spend on anything, let alone more armed forces. And so Gamble assessed St. Louis banks $150,000, with repayment to come from taxes or assessments on disloyal citizens. Schofield concurrently assessed secessionists in St. Louis County the sum of $500,000 to pay for the EMM’s arms, clothing and subsistence.

The temptation to take from neighbors, whether out of spite, greed or both, was too great. Assessment boards levied sums based on mere claims that one person or another was disloyal or had made questionable statements. Within months, prominent Missouians such as William Greenleaf Eliot were urging the suspension of the program because it was shot through with errors and, inevitably, corruption. The local civil and military authorities disclaimed any attempt to rectify the situation, each claiming that it was the other’s responsibility to do so. As with other controversies arising out of local Missouri squabbles, the matter worked its way to the president’s desk. Lincoln suspended the policy in December, and in January 1863, the War Department ended it altogether.

Or so it thought. Several commanders in the field decided that the policy was too valuable to comply with presidential orders and continued to make assessments against suspected Rebels. Some, like arch radical Benjamin Loan, suggested that those assessed could make a “donation” if they chose—as long as they paid.

Union commanders once again resorted to assessments in 1864, but General William Rosecrans limited them to pay for specific cases where the head of a family had been killed or wounded by guerrillas or the Confederate army. In one instance, Rosecrans revived the Pope assessments and collected the cost of repairing a railroad bridge over the Salt River from Monroe and Shelby Counties. To the anger of Radical Republicans, Rosecrans refused to assess secessionists to pay for the cost of providing relief to the thousands of persons who fled to St. Louis in the fall of 1864 to escape the guerrillas and Price’s invading army. General Grenville Dodge, who replaced Rosecrans, was more favorably disposed to assessments and did allow some to be made against the property of known secessionists to pay for renovations to a hospital. But by February 1865, Lincoln had again suspended the program. With the lifting of martial law in March and the end of the war in April, the assessment of citizens finally stopped.

As a policy to stop or discourage guerrilla warfare in the state, assessments were, as W. Wayne Smith said, “a distinct failure.” As a method of financing refugee relief, assessments were effective in raising needed funds. But in both situations, assessments caused deep-seated resentment. And like many harsh Union policies, they only entrenched secessionists in their hatred of the federal government—a hatred that was exacerbated by perceived (and in many cases, accurate) notions that the assessments were the result of revenge, abuse and corruption.