5

LIVING WITH SOLDIERS AND GUERRILLAS: RURAL MISSOURI IN 1862

For many in rural Missouri, the war began with celebrations. Troops paraded, flags were presented, florid speeches were made and men marched off to war to the sound of cheering crowds. It was the culmination of excitement that had been building during the 1860 election and especially after the election of the “Black Republican,” Abraham Lincoln.

A resolution adopted at a mass meeting in Marshall in December 1860 warned that “unfriendly actions” by Northern states in refusing to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law evinced a determination to interfere with the constitutional rights of the South. Moreover, if the Republican president acted in accordance with the principles upon which he had been elected, “it will be a just cause for dissolution of the Union.” At a similar meeting in Fayette, a resolution acknowledged the same grievances but cautioned that “the proper remedy is not to dissolve the union and fight against the constitution, but to stand by the union and maintain the constitution and enforcement of the laws.”

One hundred women in Fayette resolved to sew a United States flag to be presented to the person who would vote to stay in the Union at the upcoming convention called by Governor Jackson to consider secession. Jane Lewis made the presentation address:

The time of danger is at hand. Our republic is shaken to the centre. The American union, the standard bearer in the onward march of nations, has paused in its splendid career! Our constitution, the ablest work of…mortal minds is decried and attacked. Our beloved country, our mighty and magnificent union, is convulsed by a moral earthquake…To man belongs the privilege of defending in the council and on the field the honor of his country, and the rights of its citizens. Woman can only weep over the woes of her native land, and pray to the Great Ruler, in whose hands are the destinies of all nations, and trust, implicitly trust, to the wise heads, the stronger arms, the braver hearts of her countrymen.

Lewis warned that—perhaps more presciently than she realized at the time—“disunion means war, civil and servile war…[and] war’s tremendous horrors…outraged women, murdered children, burning homes…a desolated country…a ruined race.”

But events in the summer of 1861 convinced many men and women who had hoped that war could be avoided to opt for secession instead. Although couched in terms of “resisting invasion,” the celebratory events in fact meant they cast their vote for the South. James Bagwell in Macon was the first to raise South Carolina’s Palmetto flag—which remained flying until Iowa troops occupied the town and tore it down. At Boonville, enthusiasts raised the Palmetto flag over the courthouse and listened to a stirring secession speech by attorney George Vest. Vest argued that the state should proclaim itself neutral until it was well armed and then cast its lot with the South. (Vest later represented Missouri in the Confederate Congress.) Local women changed their prayers from the president of the United States to praying for Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy. A committee of citizens from Boonville visited a newly arrived relative of a prominent abolitionist to inform him that “this climate would not suit him, and as they were so solicitous of his health, he left in a hurry.”

The Palmetto flag was also raised at Savannah in Andrew County. In St. Joseph, the mayor and future Confederate general, M. Jeff Thompson, led a mob to the post office, climbed a ladder, tore down the United States flag and threw it in the street. He wrote later, “I had cut down the flag I once loved. I had as yet drawn no blood from its defenders, but I was now determined to strike it down wherever I found it.”

In Marshall, John Marmaduke (also a future Confederate general and, after the war, Missouri governor) raised the Saline Jackson Guards. Just before he led his men to Jefferson City, the ladies of Saline County, led by Sue Isaacs, presented his men with a battle flag embroidered with the state coat of arms. Isaacs praised their valor and patriotism and their service in the “glorious cause you have so nobly espoused.” Marmaduke responded in equally baroque terms, vowing “to repel the invasion of our territory and of our liberties as a state.” To the women he said: “It is for you that we fight. The weakness of woman is no defense against the violence of fanaticism…[O]ur energy [will not be] abated until the barbarian emissaries of a ruthless tyrant shall be driven beyond our borders.”

These were fine words, but in the event, the Saline Jackson Guards were routed in their first action at Boonville on June 17. The civilians of Boonville and Cooper County were left in the control of General Lyon and his “Dutch” soldiers. Nancy Chapman Jones, the wife of prominent merchant Caleb Jones, lost faith in the secessionist soldiers. She mentioned one who “was said to have done some of the finest running on the battle field” and who “threw away his gun and coat so as not to be encumbered in the race.” She reported rumors that Governor Jackson’s men had too much whiskey and too little discipline. “Jackson,” she wrote, “is evidently not the man for the times.” Federal troops arrested a number of residents, searched their homes and generally took what they wanted, whether they needed it or not. Jones wrote in May that she wished “some patriot ought to immortalize himself by hanging Frank Blair.” It was safe to make such remarks then, but now that the Federals were in control, it could be dangerous, as Dr. George Main found out. He was arrested for treason and taken before General Lyon for having said that he wished he could have a shot at Frank Blair. Lyon let him go because mere words could not constitute treason (a relatively liberal attitude that was hardly followed universally as the war dragged on). Soldiers arrested Dr. Main again shortly afterward and brought him before Lyon a second time. Main asked for a pass so that he would not have to be “subjected to the humiliation of an arrest every half hour.”Jones had nothing but scorn for the Unionists in town, such as Dr. Preston Beck—“how contemptible that fellow makes himself on all occasions.”

A few days later, however, the hard hand of Federal occupation hit the Jones family. Nancy’s son George was returning from searching for lost cattle when he saw some of Lyon’s men marching and hurrahing Lincoln and the Union. Without thinking, George hurrahed Jeff Davis. He later said he was so angry at the “Dutch rabble” overrunning the state that he spoke before he was aware of it. A Federal captain rode up to George, pointed his pistol at him and asked if he had hurrahed Jeff Davis. George admitted he had, and two guards took him away to the Union camp at nearby Pilot Grove. When George did not show up for dinner, Nancy was frantic. Her husband laughed at her worries, but that evening, a neighbor reported that George had been marched off under armed guard. Caleb sprang into action. He ordered up his carriage and rode to the Federal encampment. Officers there denied that anyone had been arrested, but after a search, Caleb found their son. Thereafter, the incident became a family joke about George joining Frank Blair’s company.

But there was little to joke about as the war continued. It became clear by the beginning of 1862, if not earlier, that the war was not going to end soon. There were no more confident assertions of the opponent’s impending defeat. Guerrilla activity ramped up, and with increased Union patrols, so did searches and imprisonments. Jane Lewis was correct. War was bringing “tremendous horror…outraged women [and] burning homes.”

The turbulent guerrilla warfare of 1862 was matched by equally turbulent political developments. Lincoln approached congressmen and senators from the border states, including Missouri, with a proposal that the Federal government would provide financial assistance if the states would begin emancipation of their slaves. It was received favorably by some of Missouri’s representatives, most notably Senator John Henderson and Representative John Noell, both of whom introduced bills to accomplish that goal. But the bills were defeated, and nothing came of the effort. On April 16, President Lincoln signed a bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. Writing from Boonville, Nancy Jones lamented that “the next thing will be to pass a similar one for all the border States.”

On July 17, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act, which enacted into law the same provisions of General Frémont’s 1861 proclamation that were so controversial less than a year before. Section 9 provided that slaves owned by Rebels who escaped to the Union army “shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.” Section 6 authorized the president to issue a proclamation warning that the property of all persons in rebellion was subject to being seized without compensation. And five days later, Lincoln drafted the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which, citing this provision, promised to free all slaves in the areas still in rebellion on January 1, 1863.

Moreover, Section 11 of the act authorized the president to enlist African Americans as soldiers in the army. None of this sat well with many Missourians, who were, after all, citizens of a loyal but slave state. Elvira Scott saw the statute as a sign of desperation. “The act will stamp infamy upon the originators of such a scheme,” she wrote. “But it will not avail.” She predicted that the “Negroes will fight for us [the South] as against their masters.” Scott was spectacularly wrong—almost 200,000 African Americans, most of them former slaves, enlisted in the Union army. More than 8,300 African Americans from Missouri served in the army, 40 percent of the eligible males (far above the percentage of eligible white males who joined the army), and that does not count the escaped Missouri slaves who made up a large percentage of the blacks serving in Kansas units.

But the Second Confiscation Act was not the governmental action that had the most immediate effect on the guerrilla war and civilians in Missouri. That was reserved for Order No. 19 and its follow up, Order No. 24. In the summer of 1862, Confederate colonels Joseph Porter, John Poindexter and John Hughes came to central and western Missouri seeking new soldiers from what they thought was a rich pool of potential recruits dissatisfied by the Union occupation. With the Union generals in Tennessee and Arkansas demanding reinforcements and the Missouri State Militia just rounding into operational form, General John Schofield’s resources were stretched thin.

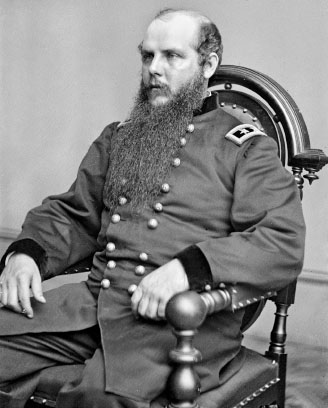

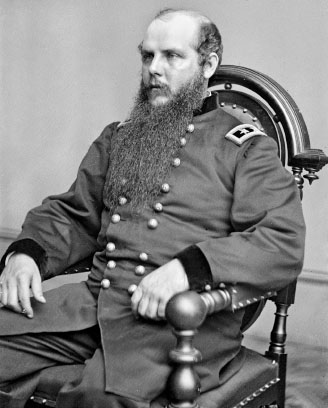

John Schofield issued controversial orders requiring all loyal men to join the militia and others to register as “disloyal.” Library of Congress.

To offset these losses, Schofield suggested to Governor Gamble that he call out additional men to serve in a state-controlled and financed militia. Gamble agreed. He directed Schofield—the commander of the Missouri State Militia (“MSM”) as well as regular Federal troops in Missouri—to order into service as many men as needed. Schofield duly issued General Order No. 19 on July 22, 1862, calling for every able-bodied man to report to the nearest military post to join the Enrolled Missouri Militia (“EMM”). By the late summer of 1862, Order No. 19 had produced an additional fifty-two thousand men. Of necessity, these units were untrained and lacked even the relatively lax discipline of the full-time MSM. A distressing number of men took advantage of their newfound military authority to harass, or even rob or kill, neighbors against whom they bore grudges or whom they suspected or knew to be Southern sympathizers.

Some Union men were troubled by Order No. 19 because it was, in effect, conscription even before the Federal government began conscription and a practice that had previously been prohibited. Governor Gamble and General Schofield did not consult higher authorities before taking this drastic step. The latter informed Washington that he suggested the measure to Gamble and ordered it into effect because the level of guerrilla violence reached the point that it was an “immediate and pressing necessity…to call at once all of the militia of the State” into service. It would have the additional ultimate benefit of allowing Schofield to release regular volunteer units for service in other theaters, such as with General Grant, who repeatedly called for more troops.

But the most controversial provision of the decree was its clarifying Order No. 24, which provided that disloyal men report to the nearest military post to register as such. They were to surrender their arms return to their homes and businesses, where—supposedly—they would not be disturbed if they “continue[d] quietly attending to their ordinary and legitimate business and in no way [gave] aid or comfort to the enemy.” Some Federal commanders anticipated, correctly, that having to register as “disloyal” would “create a stampede of secesh” to Southern arms that would bolster the forces then being gathered by recruiters such as Porter and Poindexter. And, indeed, Union soldiers distributing the order reported that the countryside was “greatly excited” about the order, and “a considerable number left their homes with intention to again in some way resist its execution.” In Southwest Missouri, Rachel Anderson confided to her diary that “secesh move off in a silent procession by the light of the moon leaving their families in the midst of their enemies.”

Southern sympathizers like Caleb Jones and John Scott were too old to have to make the choice between joining the EMM or declaring themselves disloyal. But those of military age—eighteen to forty-five—were not so lucky. Men who thought they could keep a low profile and remain neutral were going to have to declare themselves one way or another. In a civil war, neutrality was no longer an option.

Willard Mendenhall of Lexington was one such man. Before the war, Mendenhall owned a company that made carriages. His building was taken over by Federal troops for use as a commissary. Although he professed that he loved the Union and preferred to live in a slave state, he soon came to the conclusion (as nearly all Southern sympathizers did) that this was a war against slavery. Nevertheless, he chose not to join either the Confederate army or the EMM. Mendenhall believed his first loyalty was to his family, and he decided to stay home for their protection. His decision to register as disloyal brought him little sympathy from the local EMM commander, Colonel Henry Neal. When Mendenhall complained about soldiers seizing his family’s food, Neal replied, “Go to Jeff Davis for protection.” The remark was especially cutting because Mendenhall and Neal had been friends and fellow Masons before the war. Friendship now meant little.

John Brannock was attending college in Fayette at the outbreak of the war. He returned to his wife, Lizzie, and their two small children that summer. Their home was attacked by Jennison’s men, who, although the Brannocks said they were pro-Union, took nearly everything they had, sparing only their house. John was arrested, but a former classmate was an officer of the regiment and let him go. John tried to farm a family member’s place in Cass County, but Kansas troops destroyed that as well. Finally, when Order No. 19 was handed down, John decided to join “the army which he conceived to be the right one rather than go into the militia.” He believed that the order required him to choose one side or the other—trying to sit it out as Mendenhall did was not going to work for him. John and his brother Thomas managed to join a regiment in Shelby’s Missouri brigade. Presumably because of his education, John was appointed a corporal. He and his brother returned to central Missouri when Shelby led a raid from the Arkansas border to the Missouri River in October 1863. Thomas was wounded at the Battle of Marshall on October 13. John stayed behind to take care of his brother. Lizzie managed to see them at the hospital in Marshall before both were shipped off to the Gratiot Street Prison in St. Louis and later to the prison in Alton, Illinois. John and Thomas remained as prisoners of war until they were paroled in March 1865. Thus, Lizzie had to face more than two years of the war alone with their two small children.

Many women were left at home to face the uncertainties of war without their husbands, sons or fathers. More than 109,000 men from Missouri served in the Union army. About 40,000 Missourians joined the Confederate army. These numbers do not include 14,000 men who were in the Missouri State Militia for three years or the estimated 52,000 men who complied with orders to join the Enrolled Missouri Militia and served for varying periods ranging from a few days to a few months.

There is no firm estimate of the number of men who “went to the brush” and became guerrillas. Contemporary reports suggest that as many as four to five hundred guerrillas under various leaders gathered for the raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in August 1863, and a similar number participated in the Battle of Centralia, Missouri, in September 1864. The fluidity of guerrilla membership and lack of records makes it impossible to be any more precise. Although the exact number of active guerrillas operating in Missouri at any one time cannot be determined, the nature of their tactics—ambush, hit-and-run and surprise raids on towns—was such that a small number could cause a great deal of disruption.

“Formation of Guerrilla Bands,” by Adalbert John Volck, from V. Blada, Sketches from the Civil War in North America, 1861, ’62, ’63. Library of Congress.

With so many men gone, it was left to many women to assume new roles. In addition to normal prewar household duties, women now had to keep the farm running, to supervise the slaves, to protect their families. Although women were denied a political role—they could not vote, for example—they nonetheless expressed political views. And that could lead to trouble.

Elvira Scott was the fifty-year-old wife of John Scott, a successful merchant in Miami, Saline County. Miami was an important port for the shipment of hemp before the war. But after the war began, life in Miami was more a matter of survival than buying or selling. Elvira Scott was an excellent musician and amateur painter. She was also a strong secessionist with a virulent anti-German and anti-Irish bias. She kept a diary that provides one of the few contemporary day-to-day records of life in rural Missouri during the war.

Scott confided her strong views to her diary. She wrote, for example, in March 1862 that Miami was full of refugees from Jackson County who were not “active Secessionists,” but it was enough that they were “men of property, who sympathized with the Southern cause & owned Negroes.” By contrast, the Union soldiers in town were “Dutch & Irish laborers who have nothing at stake.” Better folk—people like her—were “kept under subjection by the lowest most unprincipled Dutch, with very few American hirelings.”

Scott’s disdain for the Union militia is evident from her diary and the contrast she drew between the Federal troops and the guerrillas who visited Miami. The former were ignorant, lazy, filthy and the “lowest, most desperate looking specimens of humanity it has ever been my lot to witness.” Guerrillas, on the other hand, she described as well-dressed in “picturesque style,” clean, polite, good-looking, intelligent, “refined & courteous in their manner, their language correct & gentlemanly.” Where the motives she attributed to Union soldiers were the mere desire to plunder and terrorize their betters because they had the power to do so, she admired the guerrillas for their “reckless daring,” “ready to sell their lives as dearly as possible,” driven to extreme violence only by the dangers that surrounded anyone who dared to defy the Federal government.

There might be more than mere partisan sentiment to Scott’s comments. Recent research by historians such as Mark Geiger and Don Bowen suggests that many members of the guerrilla bands (or at least of those who can be identified) came from relatively wealthy slave-owning families. The families were among the strongest supporters of secession, even going to the extent of mortgaging their land to pay for equipping such units as the Saline Jackson Guards and Shelby’s regiment. That someone like Elvira Scott, herself a member of the merchant and slaveholding elite of central Missouri, would find these men far more admirable than “foreigners” who spoke poor English is not surprising. Moreover, most of the Union soldiers Scott encountered were farmers or workingmen—she was scandalized to find out that the major commanding at Marshall was a blacksmith!

On March 11, a company of Missouri State Militia led by Captain Peter Ostermeyer rode into town—“Federals at last.” They arrested several men and moved on. But on April 26, more soldiers appeared, and this time they arrested John Scott. Authorities held him for a week but released him on parole and the posting of a $3,000 bond to guarantee his good behavior.

In recounting John’s experience, Scott wrote: “Gentlemen of the highest social &—a year ago—political position are hunted down and shot like dogs if they do not come forward & take the oath to support these usurpations.” Scott raged in her diary against the provisional state government that “arrogated to itself supreme power.” She lamented that thousands of the best men were in the South fighting for their “inalienable rights, life, liberty & the pursuit of happiness” (note that Scott, like many Southern sympathizers of the time, left out that part of the Declaration of Independence about “all men are created equal”). She believed that the “national airs” sung by the Federal soldiers were not just insincere but also beyond their comprehension. They were, she was convinced, in it strictly for the money and plunder that their position gave them license to take with impunity.

“Searching for arms,” by Adalbert John Volck, from V. Blada, Sketches from the Civil War in North America, 1861, ’62, ’63. Library of Congress.

Scott’s low opinion of the state and federal government, however, landed her in trouble. In early July, a soldier handed her a document from the local commander, Lieutenant Adam Bax, that she thought was intended for her husband until she saw her name on it. “The time has passed,” it read, “when treasonable language goes unpunished. A Ladies place is to fulfill household duties, and not to spread treason and excite men to rebellion.” She was ordered to report personally to military headquarters until such time as the commanding officer is “fully convinced that you behave yourself as a Lady Ought.” Scott was “indignant, outraged” that such an “ignorant, degraded class of men” would instruct her on the proper duties of a lady. She had never—at least publicly—uttered any treasonable sentiments, whatever she thought privately. (It apparently did not occur to Scott that private conversations in her house might be reported to Federal authorities by her slaves.)

John was incensed as well, but when a man criticized the Union soldiers, he could find himself in serious trouble. John unburdened himself to a fellow merchant. This man, whom Elvira characterized as a former “violent & uncompromising secessionist” but now a “pusillanimous sycophant,” reported John’s remarks to Lieutenant Bax. He told the lieutenant that John had called him a “contemptible puppy” and a “low-lived scoundrel.” No doubt John had used those very words, but (according to Elvira) John had said that the officer would qualify for such scorn only if (her emphasis) he had charged her out of spite or revenge.

Elvira found John held at gunpoint by a squad of soldiers. Lieutenant Bax approached her armed with three revolvers. “Madam, you shall not insult the flag of my country,” he said. Scott shot back, “I have insulted no flag but I have neither country nor flag to protect me.” Soldiers led John away to their camp at the fairground. Elvira went home, expecting to hear that her husband had been shot. He was released on parole with orders to report to Marshall for trial.

Later, Elvira led a delegation of ladies to meet Lieutenant Bax to discuss the charges against them. The charges were petty: their children called the soldiers abolitionists (Bax had to agree that many of them were); some had hurrahed Jeff Davis (the soldiers had egged them on); and another had “talked in her garden,” presumably disparaging the Union cause. They all denied making political remarks or defended their children as too small to realize what they were saying. The lieutenant did not say who the informants might be. (Again, none seem to have considered that their black servants might have told the soldiers what they had heard.) Scott proceeded to dress Bax down, pointing out that Jennison’s Jayhawkers had stolen a large number of slaves, and as far as Bax’s boast that the rebellion would be crushed, she proudly noted that Southern arms had been victorious that summer before Richmond. Scott dismissed his threats. She was not afraid of him and said that she did not come from a cowardly race—her ancestors had fought Indians in the wilderness and were native Americans for centuries. This last jab was intended to disparage Bax’s nativity, but he was too dense to realize it (or just ignored it). Bax undoubtedly was eager to end the meeting because, according to Scott, he unexpectedly found “ladies to deal with who would not condescend to be abusive, but yet did not fear him in the least. He was hardly prepared, I think, for such womanly dignity & fearlessness. He thought, I suppose, that we would come, frightened & trembling, begging his mercy.”

“Jemison’s [sic] Jayhawkers,” by Adalbert John Volck, from Blada’s War Sketches. Library of Congress.

John was held at Marshall a week, but he was acquitted in the end. Scott wrote that her husband had also bawled out Lieutenant Bax for his disrespectful language. The “little lieutenant” became frightened of the consequences if his superiors found out, and he begged the Scotts’ forgiveness. Thus, the incident closed.

The Scotts, especially John, were lucky. Both Union soldiers and guerrillas generally refrained from physical abuse of white women, and so Elvira’s tirades were bold but far less likely to result in punishment than John’s complaints. Men, on the other hand, were frequently jailed or even shot for making the kind of statements he made about Bax. And being called before the authorities by a disgruntled neighbor was hardly unusual.