6

RELIGION AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN THE MIDST OF GUERRILLA WAR

As she sat in the St. Charles Presbyterian Church, Mary Easton Sibley became agitated and then angry. Sibley was not raised to be particularly religious, but in mid-life she joined the Old School Presbyterian Church. Now, Pastor Robert Farris—her pastor—was not only talking politics in the pulpit, but he was also talking secession. It was July 1861. The state was in turmoil. Nathaniel Lyon had captured Camp Jackson in May, Union and Missouri State Guard troops clashed at Boonville in June and there were reports of men burning bridges and shooting into trains.

Federal troops under General John Pope had camped at St. Charles. And now Farris offered a prayer that “the State of Missouri might have the power granted to it by the Almighty ‘to drive out the invaders,’” an obvious reference to Pope’s Union soldiers. He further prayed that “they might be made strong to resist oppression.” Moreover, Farris had publicly declared that he was a “revolutionist.” Sibley wrote an indignant letter to the provost marshal in St. Louis demanding that Farris be dealt with.

It took over a year, but in September 1862, staunch Unionist Franklin Dick, now provost marshal, arrested Farris and put him in the Gratiot Street Prison. Dick concluded Farris was disloyal and gave him six weeks to get out of town and the state. Farris used the time to good advantage and proved that, if one has powerful local enemies, one should have even more powerful national friends.

Farris wrote to United States Supreme Court justice David Davis, a close friend of Lincoln’s, seeking help. Alerted to Farris’s maneuver, Dick wrote the president directly, arguing that “Farris is one of the most impudent, persist[ent] and ingenious Rebels in the State, and as a Minister, has wielded a powerful influence in aid of the rebellion.” Lincoln nevertheless decided that Farris could return to Missouri. Dick refused to allow Farris back in the state. The minister once again appealed to Justice Davis, and once again the president ordered Dick to allow Farris to return. This time Dick complied, presumably grudgingly. Sibley’s reaction to these events is not recorded.

Missourians took their religion seriously. Although in many ways a frontier society with its attendant rough edges, by 1860 there were 1,579 churches in Missouri. Presbyterians such as Sibley’s church accounted for 215 of them, but the majority were either Methodist Episcopal South (526) or Southern Baptist (458). The word “South” in the names was significant, for it reflected a division of previously united churches over slavery.

The tradition of what Marcus McArthur calls “apolitical theology” had deep roots in Missouri: the church had a strictly spiritual jurisdiction, and ministers should not become involved in political issues. But in the 1840s, church unity began to crack. Northern ministers agitated for the church to take a stand on the slavery issue. The matter came to a head in the Methodist Church in 1844. Bishop James Andrew of Georgia inherited slaves, and his wife owned slaves. Northern Methodists demanded that he free the slaves, but Georgia law prohibited it. After an impassioned debate, the Methodist Conference voted to suspend Andrew from office while he owned slaves. Missouri’s Methodists joined their Southern brethren in voting against suspension. Southern delegates organized the Methodist Church South in 1845, and Missouri’s conference voted to join that group. By 1859, the Methodist Church South had 44,000 members in Missouri and the Methodist Church North only 6,000.

The Baptists split along geographical lines in the slavery debate as well. The Southern Baptist Association, whose members had sought unsuccessfully to have the church endorse a policy allowing slaveholders to be missionaries, was organized in 1845. Missouri’s General Convention joined the following year.

The Presbyterians had separated in the 1830s over other doctrinal questions into Old School and New School churches. Old School Presbyterians, such as Sibley, generally sought to avoid the slavery question altogether while New School Presbyterians—like the Northern factions of the Methodists and Baptists—supported antislavery political positions.

Although there were only two Unitarian churches in Missouri at the outbreak of the war, Unitarian minister William Greenleaf Eliot was the most prominent cleric in the state. He was not only a well-known religious figure but also a founder of Washington University in St. Louis and a leader in a number of other civic activities. He also exemplified the “political” preacher who used his pulpit to promote the Union cause. Where apolitical ministers justified noninterference in political affairs based on the passage in Matthew 2:21—“Render therefore unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s”—Eliot’s take was precisely the opposite. Eliot argued that “no one who loves his country, or has any interest in its welfare, can or ought to be silent.” Neutrality was, in effect, a stance in favor of rebellion, for it was “a Christian duty to defend our country from invasion and rebellion, peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must.”

A staunch Unionist preaching in St. Louis, a city filled with Federal troops, could make such overtly political statements from the pulpit without fear. But for ministers in the countryside life was not so simple. A Northern Methodist minister in Shelbyville was threatened with a coat of tar and feathers for supporting the Union. A Baptist minister, Bartlett Anderson of Randolph County, was accused of preaching “treasonable and disloyal sentiments,” a charge he vehemently denied. He said that he never introduced politics in the pulpit and was “opposed to the preaching of politics from the pulpit or otherwise using the pulpit than for purely religious purposes.” Anderson’s protests were of no avail. He was sent to St. Louis for trial before a military commission. The commission acquitted him and ordered his release. Anderson returned home on December 8. On December 24, 1862, General Samuel Curtis issued General Order No. 35, which authorized provost marshals and commanders to arrest “notoriously bad and dangerous men,” even without proof of any wrongdoing, and to require them to post a bond for good behavior or to imprison or banish them. General Lewis Merrill, the commander of the district that included Randolph County, was obviously dissatisfied with Anderson’s release. He immediately ordered Anderson banished to some point “east of the State of Illinois and north of Indianapolis, Indiana.” Anderson apparently did not comply with the order right away and was charged in March 1863 with having made numerous statements in support of the Confederacy. The authorities sent him before another military commission. What happened next is unclear (perhaps he was found guilty but paroled), but in any event, Anderson was allowed to remain in St. Louis.

Robert Farris ran afoul of the authorities for public prayers opposing Union forces, but ministers did not have to go that far in more sensitive areas. Lexington was a hotbed of secession sentiment and sent many men to the Confederate army and guerrilla bands. As late as 1865, when Northern victory was ensured, Southern Methodist minister W.B. McFarland was removed from the pulpit merely for failing to lead his congregation in special prayers of thanksgiving for recent Northern military victories.

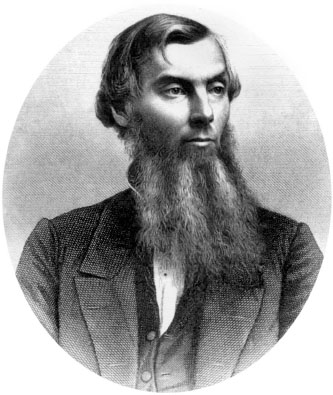

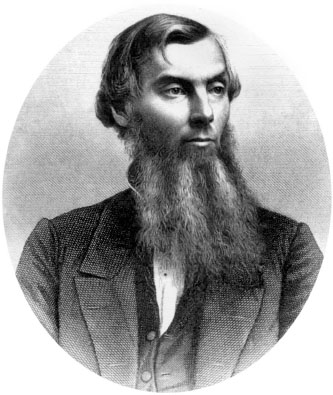

Samuel McPheeters was the center of a controversy over whether ministers had to preach sermons in favor of the Union. From John Grasty, Memoir of Rev. Samuel B. McPheeters, 1871.

The most well-known case of military interference with religious affairs involved Old School Presbyterian minister Samuel McPheeters of the Pine Street Presbyterian Church in St. Louis. Unlike Robert Farris, who publicly made his political views known, McPheeters refrained from any such comments from the pulpit on the basis that the “Church…owes its allegiance only to Jesus Christ.”

But in the tense atmosphere of St. Louis in the summer of 1862, when Federal forces were suffering defeats, guerrillas were terrorizing Unionists in the countryside and Confederate officers were roaming North Missouri recruiting hundreds of men, neutrality was seen by ardent Unionists as endorsement of the rebellion. And then, on Sunday, June 8, Samuel Robbins and his wife brought their newborn son to the Pine Street Church to be baptized before a congregation that included such staunch Unionists as attorney George Strong. When asked what name the family chose, they responded “Sterling Price Robbins,” no doubt to the gasps of many of the faithful. Later, McPheeters claimed that when he was first told that was to be the child’s name, he thought it “a jest,” and he was just as surprised as anyone else when he learned that Robbins was serious. Believing, as he later told President Lincoln, that he had no choice, he proceeded with the ceremony. Thus began another prolonged Missouri dispute that could only be ended by the president himself.

On June 18, Strong and twenty-nine other church members wrote to McPheeters, charging that the baptism of Sterling Price Robbins was “a premeditated insult to the government and all its friends in the Pine Street Church…a public and sacrilegious prostitution of a sacred ordinance of God’s house, to the gratification…of the most contemptible and malicious feelings of hostility to ‘the powers that be.’”

In December 1862, both sides of the controversy published letters setting forth their positions. On December 19, the government took action. Provost Marshal Dick ordered McPheeters and his wife banished. Dick’s justification for the order (issued without even a hearing before a military commission) was that McPheeters “refuses to declare whether he is in favor of the success of the authorities of the nation in their efforts to put down a cruel and desolating rebellion.” Dick also ordered that the Pine Street Church and its records be turned over to a committee of its members headed by George Strong.

Following the principle that persons with powerful local enemies need powerful national friends, McPheeters sought the help of Attorney General Edward Bates, a family friend and fellow Presbyterian. McPheeters traveled to Washington, where Bates accompanied him to a personal interview with the president on December 27. Lincoln listened as McPheeters read a prepared statement. The president asked about the “most singular baptism.” Bates pointed out that McPheeters followed church law in baptizing the child with the parents’ chosen name, and he further noted the extraordinary nature of the provision in Dick’s order whereby the military was seizing a church, not for a hospital, but for a church where the military would prescribe the content of the sermons.

Lincoln was noncommittal at the meeting but ended up sending an order to the commander of the department, General Samuel Curtis, directing that the banishment order be lifted. Curtis and Dick protested, but Lincoln noted that there was no actual evidence against McPheeters, just a “suspicion of his secret sympathies.” He cautioned “that the U.S. government must not, as by this order, undertake to run the churches.” Military authorities could deal with anyone who posed a danger to the “public interest,” Lincoln wrote, “but let the churches as such, take care of themselves. It will not do for the U.S. to appoint Trustees, Supervisors, or other agents for the churches.”

As far as Lincoln was concerned, the matter was done. But Union authorities in Missouri were not going to let a mere presidential directive stop them from suppressing what they conceived as Confederate sentiment. Although Lincoln disapproved of the takeover of the Pine Street Church, Dick left Strong’s committee in charge until March. Moreover, McPheeters still could not preach in Missouri. He attempted to resign, but his congregation asked him to remain. In late 1863, more than three dozen of McPheeters’s supporters sent letters and a petition asking the president to allow the deposed minister to resume his duties.

The president was puzzled and offended by the notion that he was somehow responsible for McPheeters’s continued predicament. Lincoln observed that one of the letter writers said, “Is it not a strange illustration of the condition of things that the question of who shall be allowed to preach in a church in St. Louis shall be decided by the President of the United States?” The president was probably thinking the same thing. He denied depriving McPheeters of “any ecclesiastical right, or authorized, or excused its being done by any one deriving authority from me…The assumption that I am keeping Dr. M. from preaching in his church is monstrous. If any one is doing this, by pretense of my authority, I will thank any one who can, to make out and present me, a specific case against him. If, after all, the Dr. is kept out by the majority of his own parishioners, and my official power is sought to force him in over their heads, I decline that also.” McPheeters returned to the pulpit in January 1864. One year later, he moved to Mulberry, Kentucky. McPheeters died in 1870.

And Samuel Robbins? He was tried by a military commission at the insistence of, among others, George Strong and banished for the temerity of naming his son after the Confederate general. After the war, Robbins returned to St. Louis. By 1888, Sterling Price Robbins was an officer of the St. Louis Vise & Tool Company.

The treatment of McPheeters and others discouraged many ministers from taking churches. And those who attempted to remain as neutral as McPheeters could run into similar troubles. For example, as part of its strictures on those who could hold certain offices, the state legislature required ministers to take loyalty oaths to be able to conduct lawful marriages. Apparently the law was not as rigorously enforced as it might have been, for in 1864, the legislature passed another law legitimizing any marriages performed by clergy who had failed to take the oath.

All of these political maneuvers engrossed the elite, but ordinary Missourians went to church to seek solace and hope. As one member of the Pine Street Church told Reverend McPheeters, “We have the war all the week, and want the gospel on Sunday.” Diaries and letters of the period are filled with fervent prayers. At first, many of Southern sympathies prayed for the success of the rebellion or repulse of the Union “invaders.” Soon the nature of the prayers shifted to ones for the safety of their loved ones, whether in the military, guerrillas or those who stayed home to chance the dangers of the guerrilla war from both sides. By 1863, the prayers were for the end of the war. No doubt, those of Northern sympathies felt the same.