9

MEDICAL CARE AND THE WESTERN SANITARY COMMISSION

About 6:00 a.m. on August 10, 1861, John Ray and his family heard the first shots fired from what became known as Bloody Hill across Wilson Creek, about ten miles southwest of Springfield. The Ray house sat just off the Wire Road at the top of another hill. It was the local post office and served at one time as a stop on the Butterfield Overland Stage route.

Ray sat on his porch and watched Federal troops emerge from the dense brush surrounding the creek and move across his cornfield. While the bullets flew, Roxanna Ray and her seven children, along with their slave Rhoda Ray and her three children, took refuge in the house’s cellar. Soon, Confederate soldiers arrived with wounded—lots of wounded. Every room of the house was filled with wounded men, and the yellow flag signifying it was a hospital and not to be fired upon was erected. Roxanna and Rhoda, and likely some of the older children, fetched water for the men while the surgeons and attendants treated them. No doubt the house was bloody from the open wounds and the inevitable amputations that followed. Many of the men were too injured to move and remained with the Rays for up to six weeks.

No one was prepared for the huge number of wounded and sick soldiers the war would create—not Roxanna and Rhoda Ray; not the town of Springfield, which shortly after the battle was described as a “vast hospital”; and not the city of St. Louis, which began its role as the principal medical center of the Western and Trans-Mississippi Theaters. Thousands of soldiers passed through Missouri on their way to war, and thousands returned suffering from grievous injuries, debilitating illnesses or both.

The Ray house, the only surviving building from the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, was used as a hospital. Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield.

In Springfield, the wounded from the battle filled up a hospital established in the courthouse, the Bailey House Hotel, churches and schools and, finally, thirty to forty private homes. Many of the women who remained in the town volunteered as nurses. A Confederate surgeon wrote, “The fair sex, God bless them, are doing all they can in the way of cooking, serving, and nursing for sick and wounded.” Hundreds of Union wounded were put into wagons for the rough trip over rutted roads to Rolla, where they were placed on railroad cars for St. Louis. The city was not prepared to receive them. The New House of Refuge, opened only a few days earlier, was simply an empty building with no beds, stoves or nurses. The men were laid on the bare floor, many still in the bloody clothes they wore when hit and many with the rifle balls still in their bodies. Doctors and neighbors quickly gathered food and bedclothes. Several hundred more wounded arrived within a few days.

Among those who volunteered to care for the soldiers was Adaline Couzins, the wife of John Couzins, the St. Louis police chief. She gathered bandages, lint for packing wounds and clean underwear. This was just the beginning of Adaline Couzins’s distinguished career as a nurse and medical provider to Civil War soldiers. Members of the Ladies Union Aid Society—mostly wives of merchants originally from the Northeast—also helped to provide medical care by rolling bandages, collecting clothing, reading and writing letters for injured and sick patients and providing other nursing services.

A St. Louis hospital, showing the 1864 United States flag. Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield.

The city’s elite pressured General Frémont to take action. Encouraged by his wife, Jessie, Frémont approved William Greenleaf Eliot’s plans and authorized the creation of the Western Sanitary Commission on September 5, 1861. It opened the City General Hospital in September 1861 and five more in the next two months. By May 1862, the commission had fifteen hospitals with six thousand beds available and had treated nearly twenty thousand patients.

The Western Sanitary Commission became the principal civilian organization that not only supplemented military medical care but also provided relief supplies and services to refugees, white and black, that streamed into St. Louis from outstate Missouri, Arkansas and Tennessee.

The Western Sanitary Commission did not confine its activities to St. Louis or Missouri. A delegation led by Dr. Simon Pollak followed Grant’s forces down the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. A number of prominent St. Louis women accompanied Pollak, but only two, he said, “were worth anything”—a Mrs. Kershaw and Adaline Couzins. While most of the women (“society imps,” Pollak called them) were content with fanning the brows and reading to the wounded, Couzins and Kershaw “changed the bloody, torn and muddy garments of the wounded soldiers; bathed them; performed all kinds of menial work.” Couzins’s daughter, Phoebe, met her mother when the steamer brought the men back to St. Louis. It was full of “[m]aimed, bleeding, dying soldiers by the hundreds…and boxes—filled with amputated limbs, and dead awaiting their last rites.” Adaline Couzins returned to Tennessee just in time for the aftermath of the Battle of Shiloh. There she saw the horrific results of modern warfare—men shattered by artillery shell fragments and rifle balls, covered with mud and blood. Steamboats transported nearly 3,400 patients to St. Louis from Pittsburg Landing. Adaline Couzins would make repeated trips to the field, even suffering a wound herself from a Minié ball during the siege of Vicksburg.

“Campaign sketches. The letter for home,” by Winslow Homer. Library of Congress.

In addition to medical care, the commission provided relief supplies and housing to the thousands of refugees who came to St. Louis. The first wave arrived in the late summer and early fall of 1861, fleeing Price’s army from Southwest Missouri after the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. The first round of assessments was made against Southern sympathizers to pay for the cost of housing, clothing and feeding these unfortunates. As the war dragged on, many former slaves fled their homes and came to the city to escape bondage. The women from the Ladies Union Aid Society organized a Ladies Freedmen’s Relief Association that worked with the Freedmen’s Relief Association to convert the Lawson Hospital into a home for black refugees and to create an orphanage for black children. A contraband camp was established at Benton Barracks. The group also provided a school for black children at the barracks in cooperation with the Western Sanitary Commission. When a separate hospital was opened for black troops at Benton Barracks in April 1864, a group of black women organized the Colored Ladies’ Union Aid Society to assist them.

Among the innovations pioneered by the Western Sanitary Commission were “floating hospitals,” steamboats fully equipped to follow the army down the western rivers to provide hospital care as near to the front as possible. The first boats were simply regular transports, but soon the commission had boats specially refitted to serve as hospitals. The best known was the Red Rover. It was a side-wheel steamer built in Louisville in 1857 and used by the Confederacy until it was captured at Island No. 10 in 1862. By May 1862 it was ready to join the Union fleet. The Red Rover had amputation and treatment rooms, three steam elevators to move patients between decks, a laundry, an icebox that held three hundred tons of ice, rooms for bathing, nine water closets, two kitchens and special blinds to keep out cinders from the smokestacks and insects. Unlike modern hospital ships, the Red Rover was armed; it carried a thirty-two-pounder cannon and small arms. Although it was prepared for battle on several occasions, it saw combat only once—on January 21, 1863, near Napoleon, Mississippi, a Rebel battery fired a cannon ball through its hospital ward, but no serious casualties were recorded. The ship had the distinction of having as part of its crew the first female nurses in the navy—nuns from the Sisters of Charity and at least five African American former slaves. The Red Rover supported army operations on the Mississippi at St. Charles, Arkansas, Memphis, Helena, Vicksburg and New Orleans, treating 1,697 patients.

The goods distributed and the money to pay for all of these activities of the Western Sanitary Commission primarily came from private donations. (The State of Missouri contributed $75,000, and St. Louis County gave $2,000.) The commission solicited funds from the entire country, not just the Middle and Upper Middle West. Indeed, its fundraising efforts in New England were one of the sore points in its relationship with the United States Sanitary Commission—in addition to the westerners’ refusal to become subordinate to that group.

The Red Rover was a “floating hospital” specially equipped by the Western Sanitary Commission to provide medical services close to Union lines. Library of Congress.

In the winter of 1861–62, the Ladies Union Aid Society had staged a series of tableaux vivants in the Mercantile Library with the most socially prominent women and girls. In these productions, the women emulated statues to represent classical scenes or incidents in history. Phoebe Couzins appeared in the tableaux along with the daughter of Truman Post, a Congregational minister originally from Middlebury, Vermont. Post’s daughter was said to offer “a perfect Grecian profile” as the representation of the “Goddess of Liberty.” In 1863, women decorated four rooms of the Lindell Hotel with flowers to represent the four seasons in a sylvan fête. Phoebe Couzins once again played an important role, this time leading the flower maidens as the Queen of Flowers in processions and dances.

But by 1864, the Western Sanitary Commission needed a new infusion of cash. The Ladies Union Aid Society suggested holding a sanitary fair. Other charitable organizations had successfully put on such fairs. In Chicago, for example, the United States Sanitary Commission had raised $80,000 in a twelve-day affair. The Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair was organized at a meeting on February 1, at which speeches by the mayor, General Rosecrans, William Greenleaf Eliot and others were given. A number of committees were appointed to oversee the work, including a Standing Committee consisting of the five commissioners in charge of the Western Sanitary Commission, an Executive Committee of Gentlemen and an Executive Committee of Ladies. Phoebe Couzins, as befitted her philanthropic activity, was named the ladies’ corresponding secretary. Her mother, Adaline, and a number of other prominent St. Louis women, including the wives of Frank Blair and Charles Drake, were also committee members.

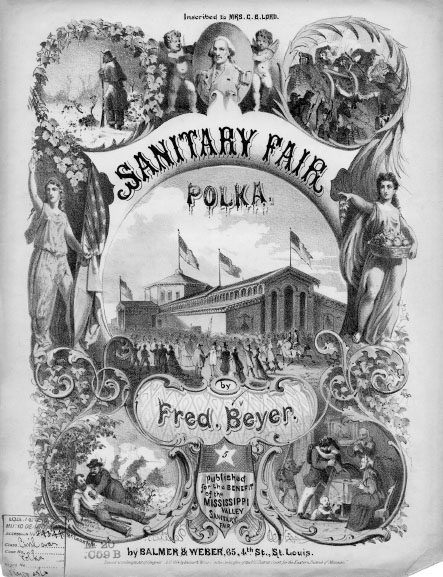

Cover of sheet music for a polka composed for the Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair of 1864 showing the main building. Library of Congress.

Organizers built a temporary structure to house the main elements of the fair on Twelfth Street (now Tucker) between Olive and St. Charles Streets on the western edge of the business district. The building was 540 feet long and 114 feet wide, with two wings, each 100 feet long, extending along Locust Street. It had an octagon center 75 feet in diameter and 50 feet high decorated with mottoes, flags, battle trophies including two cannons captured at Vicksburg and flowers. It was divided into forty-seven “apartments” or sections for displays. On one side was a stereopticon projecting slides of realistic images used to tell stories—a precursor to the motion picture.

Men from the Sixty-eighth United States Colored Infantry helped construct the buildings for which they were paid fifty cents per day. The soldiers donated their wages plus “a very considerable addition” from their “scanty monthly pay” to a separate fund created by the fair’s managers for freedmen relief.

The fair opened on May 17, with speeches and public celebrations. It opened to the public on May 18 and ran through June 18. Admission was two dollars on the opening day, one dollar the next two days and fifty cents after that. The fair featured restaurants, soda fountains, elaborate floral displays, a fortuneteller and a skating pond. The gallery of fine arts displayed a number of paintings and a wreath made of hair from the heads of generals and most of the president’s cabinet “entwined in capillary union.”

Among the biggest fundraisers were raffles. The most popular prize was Smizer’s Farm, a five-hundred-acre place near Fenton in St. Louis County valued at $40,000, apparently confiscated for failure to pay assessments and donated by the county government. William Smizer was long suspected of secessionist sentiments. He refused to take the loyalty oath because he objected to its provision that the oath was “freely given.” When soldiers visited the farm, the commander reported that Mrs. Smizer was “very mean,” insulting the soldiers as “d____d dutch fools.” Mrs. Smizer was banished in May 1863, along with a number of prominent Southern sympathizers. Fifty thousand tickets were sold at one dollar apiece; the farm was won by a Captain L.P. Martin from Iowa. A second raffle that drew much attention was the closing night’s drawing for three bars of silver from Nevada valued at $4,000 each. Other prizes included a rosewood piano, a Turkish tiger rifle, a billiard table, horses and a model steamboat.

Organizers sent invitations to President Lincoln and General Ulysses Grant, but neither was able to attend due to pressing duties in the East. Grant was at that moment involved in the heavy fighting at Spotsylvania. His wife and children not only attended the fair but also were participants. Nellie, the Grants’ nine-year-old daughter, played the role of the Old Lady Who Lived in a Shoe, surrounded by dolls representing her children. Julia Dent Grant recalled the event in her memoirs.

Nellie Grant sold dolls for fifty cents as the Old Lady Who Lived in a Shoe at the Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair. Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.

Nellie was delighted with her metamorphosis, seated as she was in a mammoth black pasteboard shoe filled with beautiful dolls of all sizes. Nellie wore over her pretty curls a wide, ruffled cap and a pair of huge spectacles across her pretty, rosy, dimpled face. She was delighted with the selling of her dolls and pictures, telling me the ladies gave her a half dollar for every doll and every picture.

The fair accomplished everything its organizers hoped for. It provided an entertaining and educational diversion for a city and state grown weary of years of brutal warfare. And in monetary terms, it was an enormous success. The Executive Committee of Gentlemen (although women provided the impetus and much of the labor and goods sold, men still made the “important” decisions) reported the fair had gross receipts of $618,782 and a net profit of $554,591. Most of the revenues—$345,000—went to pay for medical supplies, clothing and other articles for use in the commission’s hospitals and hospital boats. The Ladies Union Aid Society received $50,000 for its use in providing services to local hospitals. The fair gave $64,000 for the relief of refugees and freedmen. Another special fund for black refugees totaled $6,115, and the fair established a $1,000-per-month annuity for the Ladies Freedmen Relief Association. Proceeds of the fair were also used to establish a Soldiers’ Orphan Home in Webster Groves.

The Western Sanitary Commission continued in existence after the war. It was finally disbanded in 1886 after the death of William Greenleaf Eliot, whose brainchild it was. The commission’s remaining assets were donated to a nursing school named in his memory.